Abstract

Objectives

The association between hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and cardiovascular disease remains uncertain. This study explored long-term hard endpoints (ie, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke) and all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection in Taiwan from 2000 to 2013.

Design

This study was retrospective, longitudinal and propensity score-matched.

Setting Nationwide claims data for the period 2000–2013 were retrieved from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database.

Participants

The study included 40 162 diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection (HBV cohort) and 40 162 propensity score-matched diabetic patients without HBV infection (control cohort). Chronic HBV infection was identified based on three or more outpatient clinic visits or one hospital admission with a diagnosis of HBV infection.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE, including myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke), heart failure and all-cause mortality.

Results

During the median follow-up period of 5.3±3.4 years, the HBV cohort had significantly lower risks of myocardial infarction (adjusted HR (aHR)=0.49; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.56), ischaemic stroke (aHR=0.61; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.67), heart failure (aHR=0.50; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.59) and all-cause mortality (aHR=0.72; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.75) compared with the control cohort. The impact of HBV infection on the sequential risk of MACE was greater in patients with fewer diabetic complications.

Conclusions

Chronic HBV infection was associated with decreased risk of MACE, heart failure and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes. Further research is needed to investigate the mechanism underlying these findings.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, diabetes, hepatitis B virus, ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An unselected nationwide population with the most extensive sample of diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection available was examined, minimising the possibility of referral bias.

This study is the largest-scale examination of a diabetic HBV cohort to date.

No previous study has explored long-term hard endpoints (ie, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke) and all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection.

Liver function test results and glycated haemoglobin values were not available in the nationwide dataset.

Some personal information, including body mass index and smoking status, was not available in the administrative dataset.

Introduction

The global incidence of diabetes mellitus is increasing, and the number of patients with diabetes is expected to reach 366 million by 2030.1 Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among individuals with diabetes, and the largest contributor to the direct and indirect economic costs of diabetes.2 Diabetes and commonly co-existing conditions (eg, hypertension and dyslipidaemia) are well-known risk factors for cardiovascular complications.3 Diabetes is also the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease.4 Convincing evidence has shown that an inter-relationship between chronic inflammation and metabolic abnormalities in diabetes leads to endothelial dysfunction and vascular complications.5

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has a high prevalence and is a major public health problem in Taiwan and other countries worldwide.6 7 Chronic HBV infection may cause chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).8 Chronic HBV infection is an inflammatory condition. Other diseases with chronic low-grade inflammation have been shown to increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).9 Nevertheless, chronic HBV infection has been reported to be associated inversely with metabolic syndrome in the USA, based on the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III),10 as well as in a population-based study in Taiwan.11 The association between HBV infection and MACE, however, remains uncertain. Previous cross-sectional studies of this association have produced conflicting results.12–14 A Korean cohort study postulated that hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seropositivity was associated with decreased risks of ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction, as well as an increased risk of haemorrhagic stroke.15 A population-based prospective study conducted in Taiwan showed that HBsAg seropositivity was not associated with enhanced cardiovascular mortality during a 17-year follow-up period.16 No study to date has examined the relationship between chronic HBV infection and MACE or all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes .

Accordingly, we conducted a nationwide longitudinal cohort study to investigate the relationship between chronic HBV infection and MACE, as well as all-cause mortality, in patients with diabetes in Taiwan, which is one of the most hyperendemic areas for HBV infection in the world.17 To our knowledge, this study is the largest-scale examination of a diabetic HBV cohort.

Methods

Data sources

Data were extracted from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains anonymised secondary data that are available for research purposes. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) programme, launched in 1995, currently covers 99% of the population of 23 million people. The database comprises all registry and claims data from the NHI system, ranging from demographic data to detailed orders for ambulatory and inpatient care. Taiwan’s NHI Bureau is responsible for auditing medical payments through a comprehensive review of medical records, examination reports and results of imaging studies. If a physician fails to meet the standards for clinical practice, Taiwan’s NHI reserves the right to reject payment and may impose substantial financial penalties. Disease diagnoses are coded according to the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The diagnostic accuracy for major diseases of codes registered in the NHIRD has been validated thoroughly.18–21 In this study, we used the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients dataset, sourced directly from the NHIRD. This dataset includes all available medical registry data from a random sample of 120 000 patients diagnosed with diabetes mellitus for each year since 1999. The study was exempted from full review by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital (TCHIRB-1030603-W) because the dataset comprised de-identified secondary data.

Study design

This nationwide, population-based, observational, retrospective cohort study was conducted to determine the association between chronic HBV infection and sequential MACE in patients with diabetes. Two cohorts were enrolled in the study: the HBV cohort and a matched control cohort. The HBV cohort consisted of patients diagnosed with chronic HBV infection, defined based on three or more outpatient clinic visits with ICD-9-CM codes 070.2, 070.3 and/or V02.61, or admission with a diagnosis of chronic HBV infection between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2012.22 The index date was defined as the first day of chronic HBV infection diagnosis. Patients with the following characteristics were excluded: age <20 years, diagnosis with hepatitis C infection, fewer than three outpatient clinic visits for HBV infection, history of myocardial infarction and history of cerebrovascular disease. The control cohort comprised all patients with no diagnosis of HBV infection in the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients dataset. The exclusion criteria for the HBV cohort were also applied to the control cohort. Index dates for subjects in the control cohort were assigned randomly and corresponded to those of patients in the HBV cohort.

We used 1:1 propensity score matching and calculated propensity scores for the likelihood of diagnosis of chronic HBV infection using baseline covariates and multivariate logistic regression analysis (online supplem entary table A1). We matched one control patient with each patient in the HBV cohort with a similar propensity score based on nearest-neighbour matching without replacement, using callipers of a width equal to 0.1 SD of the logit of the propensity score.

bmjopen-2017-016179supp001.pdf (61.5KB, pdf)

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were hospitalisation for myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM code 410.x), ischaemic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 433.x, 434.x) or heart failure (ICD-9-CM code 428.x) and all-cause mortality. The MACE outcome was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke. Previous studies have validated the accuracy of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke diagnoses in the NHIRD.21 23 We also chose the occurrence of HCC as a positive control outcome and hospitalisation for appendicitis as a negative control outcome. To identify patients diagnosed with HCC, we used data from Taiwan’s Catastrophic Illness Registry, which requires pathohistological confirmation of cancer diagnoses. Both cohorts were followed until death or the end of the study period (31 December 2013).

Baseline characteristics

Data on baseline demographic characteristics, including age, sex, monthly income (in New Taiwan Dollars [NT$]: <NT$19,100, NT$19,100−NT$41,999 and ≥NT$42,000), level of urbanisation and Charlson Comorbidity Index score, were collected. Taiwan’s National Health Research Institute has defined four urbanisation levels for Taiwan. The most urbanised areas are designated as level 1, and the least urbanised areas are designated as level 4. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score reflects overall systemic health, with each increase in number reflecting a stepwise increase in cumulative mortality.24 We also identified use of medications that could confound the relationship between chronic HBV infection and the primary outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the baseline data from the study cohorts. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were compared using standardised mean differences. Propensity scores of the likelihood of diagnosis of chronic HBV infection were determined by multivariate logistic regression analysis, conditional on baseline covariates (online supplementary table A1). The incidence rates of outcomes of interest in the two groups were calculated using Poisson distributions. The cumulative incidence or risk of outcomes was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between cohorts were evaluated with the log-rank test. Cox regression models with a conditional approach and stratification were used to calculate HRs and 95% CIs for the risks of outcomes.25 Cox regression with adjustment for significant differences in covariates between groups was used to calculate adjusted HRs (aHRs). Finally, the likelihood ratio test was used to examine interactions between the occurrence of outcomes subsequent to chronic HBV infection and the following variables: age, sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, CKD, dyslipidaemia, use of insulin and adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score. Subgroup analyses were also performed accordingly.

The SQL Server 2012 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used for data linkage, processing and sampling. Propensity scores were calculated with SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All other statistical analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software (V.12.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

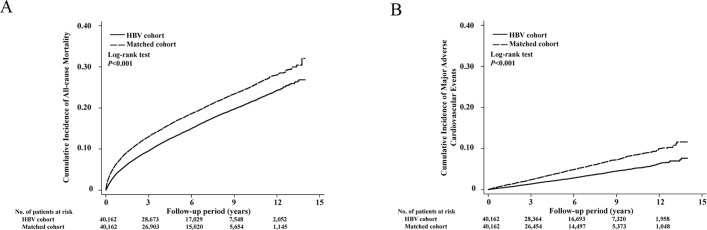

The study cohort consisted of 40 162 diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection and 40 162 matched control subjects without HBV infection (figure 1). The mean age was 52.7 (SD, 11.6 (HBV) and 11.5 (control)) years, and 62.7% of subjects were male (table 1). The prevalence of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular risk factors, and concomitant medication use was similar in the HBV and control groups.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of cohort selection. The study cohort consisted of 40 162 diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection and 40 162 matched control subjects without HBV infection. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with diabetes

| Characteristic | Propensity score-matched | ||

| HBV cohort | Control cohort | Standardised difference* | |

| Patients (n) | 40 162 | 40 162 | |

| Mean age (SD), years | 52.7 (11.6) | 52.7 (11.5) | 0.002 |

| Sex (male) | 25 173 (62.7) | 25 173 (62.7) | 0.000 |

| Monthly income, NT$ | |||

| Dependent | 8787 (21.9) | 8510 (21.2) | 0.017 |

| <19 100 | 6859 (17.1) | 6342 (15.8) | 0.035 |

| 19 100–41 999 | 18 910 (47.1) | 19 343 (48.2) | −0.022 |

| ≥42 000 | 5606 (14.0) | 5967 (14.9) | −0.026 |

| Urbanisation level | |||

| 1 (urban) | 14 845 (37.0) | 15 501 (38.6) | −0.034 |

| 2 | 23 400 (58.3) | 22 828 (56.8) | 0.029 |

| 3 | 1593 (4.0) | 1498 (3.7) | 0.012 |

| 4 (rural) | 324 (0.8) | 335 (0.8) | −0.003 |

| Outpatient visits to metabolism and endocrinology professionals in the past year | |||

| 0–5 | 35 055 (87.3) | 34 947 (87.0) | 0.008 |

| 6–10 | 3752 (9.3) | 3774 (9.4) | −0.002 |

| 11–15 | 975 (2.4) | 1049 (2.6) | −0.012 |

| >15 | 380 (0.9) | 382 (1.0) | −0.003 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, median (IQR) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–8) | 0.035 |

| Adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score, median (IQR)† | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | −0.001 |

| Median (IQR) duration of diabetes mellitus, months | 38 (12–74) | 39 (16–73) | −0.024 |

| Anti-hypertensive drug use | |||

| Alpha blocker | 420 (1.0) | 362 (0.9) | 0.015 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 3885 (9.7) | 3950 (9.8) | −0.005 |

| Beta blocker | 3256 (8.1) | 3337 (8.3) | −0.007 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 3887 (9.7) | 3866 (9.6) | 0.002 |

| Diuretic | 2701 (6.7) | 2507 (6.2) | 0.020 |

| Anti-diabetic drug use | |||

| Acarbose | 823 (2.0) | 886 (2.2) | −0.011 |

| Sulfonylurea | 7374 (18.4) | 7795 (19.4) | −0.027 |

| Insulin | 865 (2.2) | 831 (2.1) | 0.006 |

| Metformin | 6921 (17.2) | 7235 (18.0) | −0.021 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 689 (1.7) | 707 (1.8) | −0.003 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor | 398 (1.0) | 458 (1.1) | −0.015 |

| Other concomitant medications | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 2097 (5.2) | 2073 (5.2) | 0.003 |

| NSAID | 8662 (21.6) | 8728 (21.7) | −0.004 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1836 (4.6) | 1436 (3.6) | 0.050 |

| Steroid | 2005 (5.0) | 1942 (4.8) | 0.007 |

| Antidepressant | 1117 (2.8) | 1137 (2.8) | −0.003 |

| Statin | 1701 (4.2) | 1718 (4.3) | −0.002 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 9694 (24.1) | 9731 (24.2) | −0.002 |

| Hypertension | 19 839 (49.4) | 19 859 (49.4) | −0.001 |

| Heart failure | 2002 (5.0) | 1791 (4.5) | 0.025 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1369 (3.4) | 1543 (3.8) | −0.023 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5929 (14.8) | 5916 (14.7) | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 472 (1.2) | 399 (1.0) | 0.018 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 22 827 (56.8) | 23 813 (59.3) | −0.050 |

| Valvular heart disease | 2588 (6.4) | 2547 (6.3) | 0.004 |

| Cancer | 6835 (17.0) | 6546 (16.3) | 0.019 |

| Autoimmune disease | 1543 (3.8) | 1559 (3.9) | −0.002 |

| Dialysis | 386 (1.0) | 345 (0.9) | 0.011 |

| Physical limitation | 1592 (4.0) | 1606 (4.0) | −0.002 |

| Propensity score, mean (SD) | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.000 |

Data are presented as n (%) except where otherwise indicated.

*Imbalance defined as absolute value >0.014.

†A 13-point scale with seven complication categories: retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, peripheral vascular disease and metabolic. Each complication is given a numeric score ranging from 0 to 2 (0 = no abnormality, 1 = some abnormality and 2 = severe abnormality).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IQR, interquartile range; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

HBV infection, risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes

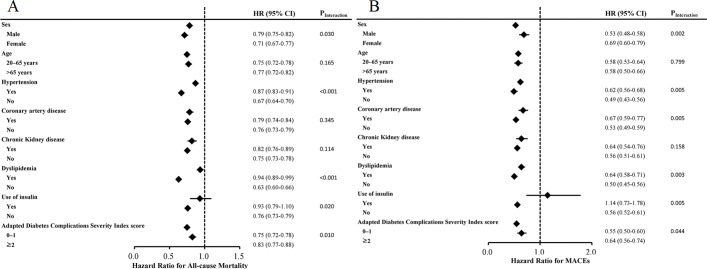

During the mean 5.3-year follow-up period, the incidence rates of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke and heart failure were 26.96, 1.38, 3.71 and 1.12 per 103 person-years, respectively, in the HBV cohort and 35.29, 2.76, 5.88 and 2.01 per 103 person-years, respectively, in the matched control cohort (table 2). Compared with the matched control cohort, the HBV cohort had significantly reduced risks of all-cause mortality (aHR=0.72; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.75; p<0.001), myocardial infarction (aHR=0.49; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.56; p<0.001), ischaemic stroke (aHR=0.61; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.67; p<0.001), MACE (aHR=0.58; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.62; p<0.001) and heart failure (aHR=0.50; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.59; p<0.001; table 2). The cumulative incidences of all-cause mortality and MACE in both groups are illustrated in figure 2. The HBV cohort had a significantly higher risk of HCC (aHR=7.47; 95% CI 6.53 to 8.56; p<0.001) and a similar risk of hospitalisation for appendicitis (aHR=1.13; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.38; p=0.227).

Table 2.

Incidence and risks of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalisation for heart failure and cancer after propensity score matching

| HBV cohort | Control cohort (reference) | Crude | Adjusted | |||||||

| No of events | Person-years | Incidence rate* | No. of events | Person-years | Incidence rate* | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR† (95% CI) | p value | |

| All-cause mortality | 6027 | 2 23 588 | 26.96 | 7140 | 2 02 307 | 35.29 | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.70 to 0.75) | <0.001 |

| MACE‡ | 1098 | 2 20 605 | 4.98 | 1663 | 1 98 131 | 8.39 | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.64) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.53 to 0.62) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 308 | 2 22 847 | 1.38 | 554 | 2 01 078 | 2.76 | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.57) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.42 to 0.56) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 822 | 2 21 298 | 3.71 | 1171 | 1 99 259 | 5.88 | 0.63 (0.57 to 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.56 to 0.67) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 249 | 2 23 050 | 1.12 | 405 | 2 01 494 | 2.01 | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.65) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| HCC | 1590 | 2 20 573 | 7.21 | 153 | 2 02 145 | 0.76 | 9.58 (8.12 to 11.31) | <0.001 | 9.34 (7.91 to 11.03) | <0.001 |

| Acute appendicitis | 222 | 2 22 682 | 1.00 | 179 | 2 01 644 | 0.89 | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.37) | 0.233 | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.38) | 0.227 |

*Per 103 person-years.

†Adjusted for monthly income, urbanisation level, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor use, metformin use, sulfonylurea use, alpha blocker use, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease and heart failure.

‡Myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality (A) and major adverse cardiovascular events (B) among diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection and matched control subjects without HBV infection. HBV, hepatitis B virus.

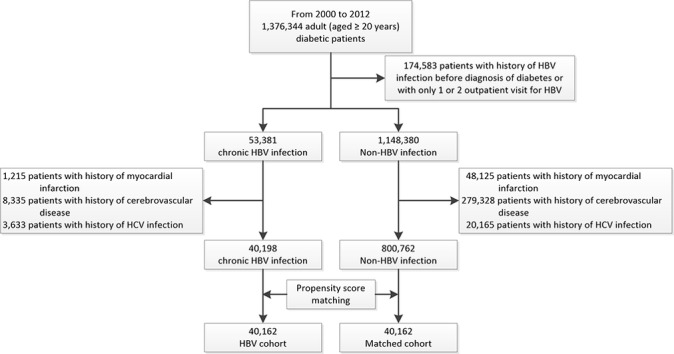

An interaction test for all-cause mortality showed significant correlations between HBV infection and sex (p=0.030), hypertension (p<0.001), dyslipidaemia (p<0.001), use of insulin (p=0.020) and adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score (p=0.010 (online supplementary table A2)). An interaction test for MACE showed significant correlations between HBV infection and sex (p=0.002), hypertension (p=0.005), coronary artery disease (p=0.005), dyslipidaemia (p=0.003), use of insulin (p=0.005) and adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index score (p=0.04 (online supplementary table A3)). Figure 3 shows the results of multivariable stratified subgroup analyses. The effects of chronic HBV infection on all-cause mortality and MACE were greater in patients without hypertension and dyslipidaemia than in matched controls. The association between chronic HBV infection and all-cause mortality or sequential MACE was also greater in patients who were not using insulin. In stratified analyses, the effect of chronic HBV infection on the sequential risk of MACE was greater in patients with low (<2) adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index scores (online supplementary table A2 and A3).

Figure 3.

Results of multivariable stratified subgroup analyses, showing the effects of chronic HBV infection on all-cause mortality (A) and major adverse cardiovascular events (B). HBV, hepatitis B virus; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this propensity score-matched, nationwide, population-based study is the first to elucidate the correlation of chronic HBV infection with lower risks of MACE and heart failure in patients with diabetes. In addition, we found a significantly decreased risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection during the mean 5.3-year follow-up period. The impact of HBV infection on the sequential risk of MACE was greater in patients with fewer diabetic complications.

This study has several strengths. First, it involved an unselected nationwide population with the most extensive sample of diabetic patients with chronic HBV infection available, minimising the possibility of referral bias. Second, the diabetic HBV cohort comprised 40 162 patients during the 12-year study period, providing adequate statistical power for analysis of the risks of MACE, heart failure and all-cause mortality (all hard endpoints) in this population. To our knowledge, this study is the largest-scale examination of a diabetic HBV cohort to date. In addition, we compared study subjects with propensity score-matched control subjects, instead of conducting age-adjusted and sex-adjusted analyses in comparison with a general population. Competing risks are the rule in clinical epidemiological studies.26 Use of the Kaplan-Meier method may lead to overestimation of the event (MACE) risk in the presence of the competing risk (death).26 However, we found reduced risks of MACE and all-cause mortality in the diabetic HBV cohort. These results would remain robust in the presence of competing risks. Furthermore, the risks of all-cause mortality and MACE in our study were comparable with the previously published data.27 28

Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, absolute values from liver function tests were not available in the nationwide dataset. An individual with chronic HBV infection may present as a ‘healthy’ carrier with normal liver function or with chronic hepatitis. Second, data on glycated haemoglobin concentration, used widely as a glycaemic control index, were not available in this dataset. Glycaemic control may be a confounding factor for MACE. However, recent reports have suggested that reduction of the blood glucose level has no beneficial effect or only modest effects on diabetic cardiovascular complications in high-risk populations.29 30 In addition, the emergence of MACE caused by poor glycaemic control is a lengthy process.29 Third, some personal information, including body mass index and smoking status, was not available in the administrative dataset, preventing accurate assessment of the contributory and confounding effects of these factors. The effects of chronic HBV infection on MACE may be due to residual confounding. However, we performed a sensitivity analysis that included positive and negative control outcomes to provide further support for our findings.31 Fourth, this observational study provided clinically relevant risk estimates without speculating on causation.

Cross-sectional studies conducted as part of the NHANES III10 and in Taiwan11 have documented an inverse association between metabolic syndrome and chronic HBV, supporting our findings. A recent systemic review revealed that many, but not all, relevant studies have shown that patients with chronic HBV infection have lower risks of metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidaemia.32 A study of a non-diabetic Korean cohort showed that HBsAg seropositivity was associated with decreased risks of ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction, secondary to HBV-associated liver dysfunction.15 Other reported mechanisms potentially linking chronic HBV infection to a decreased risk of MACE include lower levels of clotting factors II and VII and fibrinogen among HBsAg-positive (vs -negative) individuals, as found in blood donors in Gambia and London.33

A cohort study from England and Wales showed no significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality in transfusion donors with HBV infection compared with donors without HBV infection.34 In that study, the standardised mortality rate for circulatory disease was significantly lower in both males and females with hepatitis B.34 These results may support our findings. Furthermore, the risk of circulatory disease-related death in our HBV cohort was significantly lower than in an Australian study,35 comparable to that reported in another Taiwanese study,16 and significantly higher than that found in a study conducted in China.36 The Chinese study examined the period 1992–2002 and the HBV cohort had very low cardiovascular mortality rates (20.6 and 16.4 per 100 000 person-years in males and females, respectively).36 The study conducted in Taiwan showed that HBsAg seropositivity was not associated with atherosclerosis-related mortality risk in the general population.16 One possible explanation for this result is the lack of statistical power (HR=0.84; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.06) due to the small sample (480 cases of death from atherosclerotic disease).16 Results of Australian and British studies are in agreement with our findings regarding the relationship between HBV and MACE.34 35

Moreover, previous cohort studies have shown that the increased risk of all-cause mortality can be attributed mostly to excesses of liver-related deaths in the general populations.16 35 36 In the Australian study, the risk of death was increased 1.4 times in subjects with HBV infection35; this risk was increased 1.7 times in Taiwan16 and threefold in China.36 We are not aware of any study that has examined the relationship between all-cause mortality and chronic HBV infection in patients with diabetes. We conducted this HBV study in a population with a very high risk of MACE. In our diabetic cohort, the incidence rate of MACE was high (498 vs 839 per 100 000 person-years) to provide sufficient endpoints (1098 vs 1663 events). Our study demonstrated a reduced all-cause mortality risk in diabetic subjects with chronic HBV infection. This finding may be explained by the decreased MACE risk in our diabetic HBV cohort. Diabetes, which is considered to be a coronary artery disease equivalent, is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease.37 Cardiovascular complication is the leading cause of mortality in patients with diabetes.3 Thus, the impact of HBV infection on all-cause mortality could plausibly be hypothesised to be greater in patients with diabetes than in the general population.

Conclusion

In this nationwide, longitudinal, propensity score-matched analysis, chronic HBV infection was associated with decreased risks of MACE, heart failure and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes. These findings may provide new insight into the pathogenesis of diabetes and future therapeutic strategies. However, further research is needed to confirm our findings and to explore the underlying mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-TC, the guarantor of this work, had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Study concept and design: C-SK, P-HH, Y-TC and S-JL. Acquisition of data: Y-TC, C-YH and C-CC. Analysis and interpretation of data: C-SK, Y-TC and P-HH. Drafting of the manuscript: C-SK, Y-TC, P-HH, C-YH and C-CC. Statistical analysis: P-HH and Y-TC. Administrative, technical and/or material support: R-HC, S-JL, S-CK, J-WC and S-JL. Critical revision: Y-TC, P-HH and S-JL. Study supervision: P-HH and S-JL. The corresponding authors have the right to grant on behalf of all authors and do grant on behalf of all authors a worldwide license to the Publisher and its licensees in perpetuity.

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 104-2314-B-075-047, MOST 106-2633-B-009-001), from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW106-TDU-B-211-113001) and from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V105C-207, V106C-045). These funding agencies had no influence on the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Because the dataset comprised de-identified secondary data.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital (TCHIRB-1030603-W)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors have obtained nationwide claims data for the period 2000–2013 from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). NHIRD does not permit external sharing of any of the data elements. No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. . Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–53. 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eckel RH, Kahn R, Robertson RM, et al. . Preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a call to action from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2006;113:2943–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, et al. . Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2007;30:162–72. 10.2337/dc07-9917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, et al. . Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999-2010. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1613–24. 10.1056/NEJMsa1213829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Domingueti CP, Dusse LM, Carvalho M, et al. . Diabetes mellitus: the linkage between oxidative stress, inflammation, hypercoagulability and vascular complications. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:738–45. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kao JH, Chen DS. Global control of hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:395–403. 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen CL, Yang JY, Lin SF, et al. . Slow decline of hepatitis B burden in general population: results from a population-based survey and longitudinal follow-up study in Taiwan. J Hepatol 2015;63:354–63. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen DS. From hepatitis to hepatoma: lessons from type B viral hepatitis. Science 1993;262:369–70. 10.1126/science.8211155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Domingueti CP, Dusse LM, Carvalho M, et al. . Diabetes mellitus: the linkage between oxidative stress, inflammation, hypercoagulability and vascular complications. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:738–45. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jinjuvadia R, Liangpunsakul S. Association between metabolic syndrome and its individual components with viral hepatitis B. Am J Med Sci 2014;347:23–7. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31828b25a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jan CF, Chen CJ, Chiu YH, et al. . A population-based study investigating the association between metabolic syndrome and hepatitis B/C infection (Keelung Community-based Integrated Screening study No. 10). Int J Obes 2006;30:794–9. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Völzke H, Schwahn C, Wolff B, et al. . Hepatitis B and C virus infection and the risk of atherosclerosis in a general population. Atherosclerosis 2004;174:99–103. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tong DY, Wang XH, Xu CF, Cf X, et al. . Hepatitis B virus infection and coronary atherosclerosis: results from a population with relatively high prevalence of hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1292–6. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Takahashi E, et al. . Increased prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis in hepatitis B virus carriers. Circulation 2002;105:1028–30. 10.1161/hc0902.105718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sung J, Song YM, Choi YH, et al. . Hepatitis B virus seropositivity and the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction. Stroke 2007;38:1436–41. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.466268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang CH, Chen CJ, Lee MH, et al. . Chronic hepatitis B infection and risk of atherosclerosis-related mortality: a 17-year follow-up study based on 22,472 residents in Taiwan. Atherosclerosis 2010;211:624–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. . Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65–73. 10.1001/jama.295.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chao TF, Liu CJ, Chen SJ, et al. . Hyperuricemia and the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation--could it refine clinical risk stratification in AF? Int J Cardiol 2014;170:344–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chiu CC, Huang CC, Chan WL, et al. . Increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide population-based study. Intern Med 2012;51:17–21. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, et al. . Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2005;104:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, et al. . Validation of the National Health Insurance Research database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:236–42. 10.1002/pds.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu CY, Lin JT, Ho HJ, et al. . Association of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy with reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a nationwide cohort study. Gastroenterology 2014;147:143–51. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheng CL, Lee CH, Chen PS, et al. . Validation of acute myocardial infarction cases in the national health insurance research database in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2014;24:500–7. 10.2188/jea.JE20140076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Austin PC. A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med 2008;27:2037–49. 10.1002/sim.3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Andersen PK. The clinical course of cirrhosis: the importance of multistate models and competing risks analysis. Hepatology 2015;62:292–302. 10.1002/hep.27598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tseng CH. Factors associated with cancer- and non-cancer-related deaths among Taiwanese patients with diabetes after 17 years of follow-up. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147916 10.1371/journal.pone.0147916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hsieh HM, Lin TH, Lee IC, et al. . The association between participation in a pay-for-performance program and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Prev Med 2016;85:53–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayward RA, Reaven PD, Wiitala WL, et al. . Follow-up of glycemic control and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2197–206. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ACCORD Study Group. Nine-Year effects of 3.7 years of intensive glycemic control on cardiovascular outcomes. Diabetes Care 2016;39:701–8. 10.2337/dc15-2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 2010;21:383–8. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jarcuska P, Drazilova S, Fedacko J, et al. . Association between hepatitis B and metabolic syndrome: current state of the art. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:155–64. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meade TW, Stirling Y, Thompson SG, et al. . Carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen: possible association between low levels of clotting factors and protection against ischaemic heart disease. Thromb Res 1987;45:709–13. 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90336-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Crook PD, Jones ME, Hall AJ. Mortality of hepatitis B surface antigen-positive blood donors in England and Wales. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:118–24. 10.1093/ije/dyg039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Amin J, Law MG, Bartlett M, et al. . Causes of death after diagnosis of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection: a large community-based linkage study. Lancet 2006;368:938–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69374-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen G, Lin W, Shen F, et al. . Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and mortality from non-liver causes: results from the Haimen City cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:132–7. 10.1093/ije/dyh339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, et al. . Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998;339:229–34. 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016179supp001.pdf (61.5KB, pdf)