Abstract

Introduction

Many patients with stroke have moderate to severe long-term sensorimotor impairments, often including inability to execute movements of the affected arm or hand. Limited recovery from stroke may be partly caused by imbalanced interaction between the cerebral hemispheres, with reduced excitability of the ipsilesional motor cortex while excitability of the contralesional motor cortex is increased. Non-invasive brain stimulation with inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the contralesional hemisphere may aid in relieving a post-stroke interhemispheric excitability imbalance, which could improve functional recovery. There are encouraging effects of theta burst stimulation (TBS), a form of TMS, in patients with chronic stroke, but evidence on efficacy and long-term effects on arm function of contralesional TBS in patients with subacute hemiparetic stroke is lacking.

Methods and analysis

In a randomised clinical trial, we will assign 60 patients with a first-ever ischaemic stroke in the previous 7–14 days and a persistent paresis of one arm to 10 sessions of real stimulation with TBS of the contralesional primary motor cortex or to sham stimulation over a period of 2 weeks. Both types of stimulation will be followed by upper limb training. A subset of patients will undergo five MRI sessions to assess post-stroke brain reorganisation. The primary outcome measure will be the upper limb function score, assessed from grasp, grip, pinch and gross movements in the action research arm test, measured at 3 months after stroke. Patients will be blinded to treatment allocation. The primary outcome at 3 months will also be assessed in a blinded fashion.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. The results will be disseminated through (open access) peer-reviewed publications, networks of scientists, professionals and the public, and presented at conferences.

Trial registration number

NTR6133

Keywords: stroke, clinical trial, arm, rehabilitation, brain stimulation, intervention, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first clinical trials evaluating the effect of theta burst stimulation on motor function in patients with subacute stroke (within 2 weeks).

Long-term follow-up period up to 1 year after stroke onset, enabling assessment of durability of treatment effects.

Multiple, different outcome measures, including motor function, activities of daily living and neural network activity.

Participants are blinded to their allocated treatment group throughout the trial, but study personnel is only blinded for the primary outcome measurement at 3 months.

Introduction

Each year >15 million people worldwide have a stroke, which is a major cause of adult disability. The most common functional deficits after stroke are sensorimotor impairments, which, in addition to functional disability, can have considerable negative effects on quality of life and societal participation.1–5 In 33%–66% of stroke patients with a paretic arm, recovery of arm function is absent or negligible in the first 6 months,6–8 and >50% do not show signs of significant arm function recovery after >5 years post-stroke.9–12 On the other hand, 5%–20% of patients with impaired arm function after stroke demonstrate full functional recovery of arm function within 6 months.6 13 Rehabilitation programs contribute to functional recovery, and significant improvements in sensorimotor function can be achieved.7 14 Several studies suggest that functional improvement after stroke may be augmented by strategies that involve neuromodulation through non-invasive brain stimulation, such as TMS, in combination with rehabilitative training.15–21

TMS provides a non-invasive and safe way to directly facilitate or suppress brain activity in cortical areas. TMS induces a current in the cerebral cortex through a coil that generates a magnetic field.22 Repetitive delivery of TMS (rTMS) with a high-frequency train of pulses is believed to enhance cortical excitability, while repetitive low-frequency TMS would suppress cortical excitability.22 23 TMS-induced reduction of cortical excitability has been associated with long-term depression (LTD)-like effects, whereas TMS-induced increase of corticospinal excitability has been associated with long-term potentiation-like effects.24 Recently, patterned protocols consisting of short trains of high-frequency TMS (30–100 Hz) alternating with rest periods in the theta frequency range (4–7 Hz) (theta burst stimulation (TBS))25 26 have been reported to provide effective and reliable paradigms for an excitatory (intermittent TBS (iTBS)) or inhibitory (continuous TBS (cTBS)) brain stimulation.27 Three pulses of stimulation are delivered at 50 Hz, given every 200 ms. TBS paradigms are particularly promising because stimulation sessions are shorter (2–3 min or less) (ie, more practical) as compared with standard rTMS protocols (20–30 min).28–31

Patients with hemiparetic stroke often have a functionally imbalanced interaction between the damaged and undamaged brain hemispheres, with reduced excitability of the ipsilesional motor cortex while excitability in the contralesional motor cortex is increased.32–39 Recent proof-of-principle studies have demonstrated that specific TMS paradigms—that is, facilitatory stimulation of the affected hemisphere to upregulate excitability or inhibitory stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere to downregulate excitability—can elicit significant behavioural improvement in recovering patients with stroke.15 20 40 41 cTBS of the intact contralesional primary motor cortex may offer the most straightforward approach, as this brain region is easily identified from single-pulse TMS-induced motor evoked potentials (MEPs), which is more complicated in the structurally and/or functionally injured ipsilesional motor cortex.42 43

The feasibility and safety of TBS in patients with hemiparetic stroke have been demonstrated in a number of studies.28–31 44 45 However, most earlier studies involved chronic stroke patients in whom post-stroke neural network reorganisation had probably stabilised already, which may constrain the therapeutic potential of TBS. The most recent of these studies was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in which chronic subcortical stroke patients were treated with iTBS of the ipsilesional motor cortex directly followed by upper limb physical therapy, daily for 10 days. Upper limb function, assessed with the action research arm test (ARAT), improved for at least 1 month after treatment compared with sham therapy.45 Until now, however, a RCT on the long-term effects of TBS treatment in patients with subacute hemiparetic stroke is lacking. Previous studies that tested TMS treatment in the subacute phase after stroke applied low-frequency or high-frequency rTMS, some had a small sample size (18–58 patients) or was not supported by a power calculation and relatively short intervention duration of 5–10 days.41 46–50 A RCT on the long-term effects of repetitive TBS in a larger patient population subacutely after stroke would provide important new insights into the therapeutic efficacy of this non-invasive and practicable intervention during an optimal time window for neurorehabilitation, especially in combination with a pragmatic upper limb training approach directly following brain stimulation.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to determine the therapeutic effect of contralesional cTBS (inhibitory stimulation) on recovery of function of the paretic arm at 3 months after ischaemic stroke. The secondary objectives are to evaluate:

the mode of action of contralesional cTBS on neural network reorganisation after ischaemic stroke, at different time points;

the therapeutic effect of contralesional cTBS on other sensorimotor functions, at different time points post-treatment and

the therapeutic effect of contralesional cTBS on disability and quality of life, at different time points post-treatment.

Methods and analysis

Study design

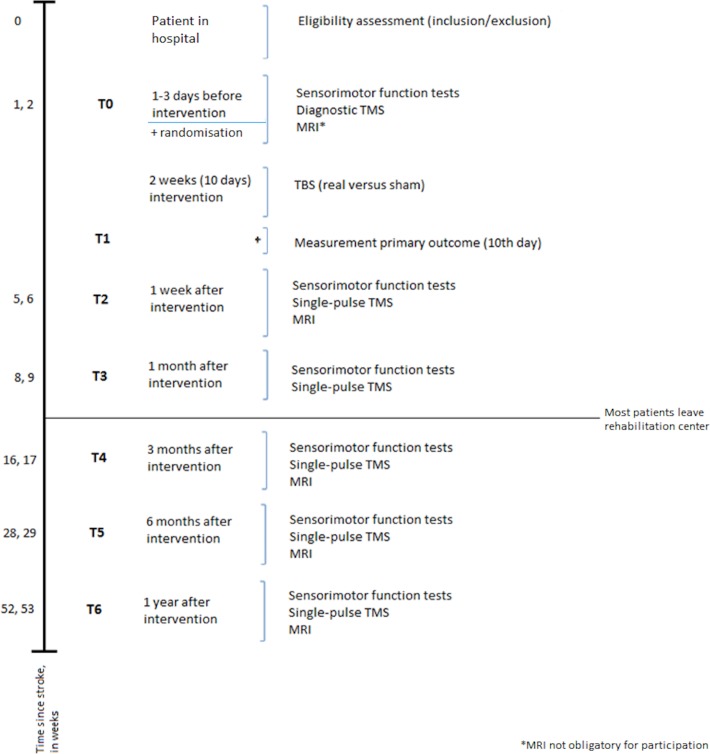

The Brain-STimulation for Arm Recovery after Stroke study is a prospective, randomised, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Subjects will be randomly allocated to real or sham brain stimulation, followed by standard care upper limb training. They will remain blinded to treatment allocation. Non-invasive brain stimulation will involve 10 daily sessions of cTBS of the contralesional hand area of the primary motor cortex over a period of 2 weeks. The first cTBS session will be executed within 2 weeks after stroke onset. Patients will be tested seven times in total (figure 1): at the start of the study (T0; baseline), at the 10th day of the intervention (T1), at 1 week (T2) and 1 month (T3) after stimulation, and at 3 months (T4), 6 months (T5) and 1 year after stroke onset (T6). All baseline and follow-up assessments, except for the primary outcome measurement, will be conducted by a trained researcher (ECCvL) with support from research assistants.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the study procedure. TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

The study has been approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

We used the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials recommendations on reporting.

Study population

Participants (total of 60) will be recruited from the University Medical Center Utrecht and rehabilitation centre De Hoogstraat in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Patients who fulfil the study criteria will be asked to participate, and they will receive a patient information letter explaining the background and methods of the study. Patients can decide to participate with or without additional MRI scanning at the University Medical Center Utrecht. After giving written informed consent, patients will be randomly allocated to the treatment procedures.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of this study are: (1) patient age ≥18 years; (2) first-ever unilateral ischaemic stroke; (3) paresis of one arm, with Shoulder Abduction and Finger Extension scores for shoulder abduction of ≥9 on the Motricity Index and for finger extension of ≥1 on the Fugl-Meyer score51; (4) admission to ‘De Hoogstraat’ within the first 2 weeks after stroke onset and (5) written informed consent. The exclusion criteria are: (1) disabling medical history (severe or recent heart disease, severe head trauma and coercively treated at a psychiatric ward); (2) history of epilepsy; (3) normal to almost normal use of hand, with a Motricity Index hand score of 33 (maximum score for this item, reflecting ‘normal’ function); (4) severe deficits in communication, memory or understanding that impede proper study participation, as determined by the treating physician and (5) contraindications for TMS (metal (implants) in skull/scalp/head or fragments from welding or metalwork, implanted device (eg, spinal cord stimulator, cardiac pacemaker and cochlear implants), pregnancy and so on).52

Randomisation

Patients will be randomly assigned to either the real cTBS or sham cTBS group, stratified to the severity of their arm paresis. Patients in the high-performance group must demonstrate a minimal ability of finger extension of the thumb or one or more fingers, while patients in the low-performance group have no ability of finger extension of the thumb or one or more fingers.53 Randomisation will be performed with a secured electronic data capture system (Research Online V.2.0, Julius Centrum). This will be done after the baseline assessment to account for possible improvements in motor function during the first days after stroke.

Intervention

All patients will receive the current standard rehabilitation programme parallel to the treatment. The rehabilitation programme consists of daily group treatment focused on the arm/hand (on functional and activity level, ca. 60 min), next to individual physical therapy, occupational therapy, creative therapy, speech therapy and so on. All therapists and other rehabilitation staff will be blinded to group allocation. In addition, real cTBS or sham cTBS in combination with upper limb training will be applied in daily sessions during 2 weeks (10 working days), starting within 7–14 days after stroke onset. TBS will be performed using a Neuro-MS/D Advanced Therapeutic stimulator (Neurosoft, Russia). cTBS will only be executed at rehabilitation centre De Hoogstraat. We will employ a standard cTBS paradigm consisting of three stimuli bursts at 50 Hz, repeated at 5 Hz frequency, resulting in 600 stimuli in 40 s.25 cTBS intensity will be at 70% of resting motor threshold (RMT), which induces highly consistent LTD-like MEP suppression with low intersubject variability.54 Sham stimulation will be done with the stimulator in the sham mode (generates pulses at 90% lower intensity of RMT), with the coil oriented at an angle of 45° relative to the scalp.20 For each session, the RMT will be determined from electromyography (EMG) (recorded with two Ag/AgCl surface electrodes) from the contralateral first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle. The motor threshold will be defined as the minimum intensity of TMS over the hand area of the contralesional primary motor cortex to elicit at least five contralateral MEPs with >50 μV peak-to-peak amplitude in 10 trials with 7 s intertrial intervals. A neuronavigation system (Brain Science Tools, the Netherlands), using a prestimulation CT or MRI scan (both techniques have been successfully applied for stereotactic imaging55 56) will be used to ensure consistent coil placement for cTBS of the hand area of the primary motor cortex. Applied protocol(s) will be in accordance with most recent safety and tolerability guidelines for TMS applications.27 57 58

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure will be the change in the modified ARAT score59 assessed at 3 months post-stroke (see table 1 for all times of testing). The ARAT is a performance test which assesses the ability to perform gross movements and the ability to grasp, move and release objects differing in size, weight and shape. The original test consists of 19 items, rated on 4-point ordinal scales (0–3), with a maximum score of 57 (best performance). By removing four items, a hierarchical one-dimensional scale has been constructed.59 The ARAT has shown good psychometric properties in patients with stroke with mild to moderate motor severity and without severe cognitive impairment. It has also evidence of unidimensionality, predictive validity and reliability. The ARAT at 3 months will be performed by an independent assessor who will be blinded to treatment allocation.

Table 1.

Overview of functional outcome measures (motor function tests and questionnaires, including timing)

| Instrument | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 |

| Motor function | |||||||

| ARAT (primary outcome measure) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| FM | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| SULCS | X | X | X | X | |||

| 9HPT | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| JTT | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Soci(et)al participation | |||||||

| SIS (hand function subscale + ‘thermometer’ of well-being) | X | X | X | X | |||

| Modified Rankin Scale | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| HADS | X | X | X | X | |||

The first assessment (T0) takes place in the first 7–14 days post-stroke. The follow-up assessments are at the last day of the stimulation session (T1); at 1 week (T2), 1 month (T3) after stimulation; and 3 months (T4), 6 months (T5) and 1 year (T6) post-stroke.

ARAT, action research arm test; FM, Fugl-Meyer score test; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; JTT, Jebsen-Taylor Test; 9HPT, Nine-hole Peg Test; SIS, Stroke Impact Scale; SULCS, Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale.

Secondary outcome measures

In addition to the ARAT score, we will measure sensorimotor function with the following tests: Fugl-Meyer score test, Nine-Hole Peg Test, Jebson-Taylor hand test and the Stroke Upper Limb Capacity Scale (SULCS) test. The Fugl-Meyer arm score test is a reliable and valid motor performance test consisting of 33 tasks executed with the affected upper limb.60 61 Performance on each task is rated as 0, 1 or 2, with higher ratings representing better performance. The Nine-Hole Peg Test examines the speed of movement of fine motor skills. The duration of the task execution will be measured. The maximum allowed time will be 50 s, during which the number of pegs is counted.62 The Nine-Hole Peg Test has demonstrated good reliability and validity and has the ability to be used across the age span.63 Hand skill will be measured with the Jebsen-Taylor hand test. The scores on all seven items, representing activities during daily living, will be summed for a total score. The Jebsen-Taylor test is a reliable and valid measure of gross functional dexterity.64 The SULCS assesses arm function capacity, and basal and complex hand function capacity. It consists of 10 items, each of which is scored with 0 or 1. The SULCS has shown good psychometric properties and assesses upper limb capacity according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health definition.65

The following outcome measurements will be used to measure dependency, quality of life and depression: modified Rankin Scale, Stroke Impact Scale and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The modified Rankin Scale assesses disability and is subdivided into six scores. Score ‘0’ corresponds to no symptoms, whereas score ‘5’ corresponds to severe handicap. When adhering to a series of rules and a structured interview, the modified Rankin Scale proved to be a reliable and valid measure.66 The Stroke Impact Scale is a self-report health status measure, specifically developed for the stroke population. This multidimensional instrument measures hand function, strength, activities of daily living, communication, emotion, memory and thinking. The Stroke Impact Scale has shown good psychometric properties in a diverse group of stroke survivors.67 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale measures the core symptoms of anxiety and depression without involving physical symptoms.68 This scale is commonly used in patients with stroke and has good psychometric properties.69

Corticospinal excitability and intracortical inhibition will be assessed from the amplitude and latency of MEP responses, respectively, induced by single-pulse TMS to the ipsilesional and contralesional primary motor cortex, measured by EMG with surface electrodes over the FDI muscle of both hands. Stimulus-response curves will be measured from 12 MEP recordings at 95%, 105%, 115%, 125% and 135% stimulus intensity relative to the RMT (in random order).

To assess patients’ functional brain status, we will measure functional MRI (fMRI)-based sensorimotor activation (eg, percentage of blood oxygenation-level dependent change) and resting-state fMRI-based functional connectivity in ipsilesional and contralesional sensory and motor regions. In addition, we will apply diffusion tensor imaging to assess structural integrity of the bilateral corticospinal tract and other white matter areas, based on different diffusion parameters (eg, fractional anisotropy). MRI will be executed on a clinical 3T scanner. Task-related fMRI will be done during flexion–extension movement of the fingers of the hand in a blocked design. Before MRI scanning, patients will be trained to perform the task correctly. The secondary outcome measures including moment of administering can be found in tables 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Overview of neural outcome measures (including timing)

| Instrument | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | |

| Brain status | ||||||||

| Corticospinal excitability and intracortical inhibition | Diagnostic TMS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ischaemic injury, white matter integrity, functional connectivity and cortical activation | (f)MRI (optional) | X | X | X | X | X |

The first assessment (T0) takes place in the first 7–14 days post-stroke. The follow-up assessments are at the last day of the stimulation session (T1); at 1 week (T2), 1 month (T3) after stimulation; and 3 months (T4), 6 months (T5) and 1 year (T6) post-stroke.

fMRI, functional MRI; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Other baseline data and parameters

The following parameters will be screened from the medical records of patients and from questionnaires to control for possible confounding effects (see table 3 for an overview and the timing):

Use of alcohol or drugs in previous 12 hours, use of caffeine in previous 2 hours and quality of last night’s sleep prior to brain stimulation

Complaints of dizziness, headache, insult, tiredness, muscle stiffness and so on after brain stimulation

Medication (that lowers the seizure threshold)

Amount of (physical) therapy and self-practice

Demographic parameters at baseline: gender, age, education level, handedness, marital status and ethnicity

Stroke-related parameters at baseline: type of stroke, stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale), side affected limb, days since stroke onset and cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment).

Table 3.

Overview of measures that are part of care as usual and extra care

| Instrument | T0 | Treatment | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 |

| Activities of daily living | ||||||||

| Barthel Index | X | X* | X* | X* | X* | X* | ||

| Demographics and stroke characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, gender, education, marital status, ethnicity, work status and handedness | X | |||||||

| MOCA | X | |||||||

| Type of stroke, stroke severity (NIHSS) and side affected limb | X | |||||||

| Other parameters | ||||||||

| Use of alcohol/caffeine/drugs, medication, (physical) therapy/self-practice and poststimulation complaints | X* | X* | X* | |||||

The first assessment (T0) takes place in the first 7–14 days post-stroke. The follow-up assessments are at the last day of the stimulation session (T1), and at 1 week (T2), 1 month (T3) after stimulation, 3 months (T4), 6 months (T5) and 1 year (T6) post-stroke.

MOCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. *, extra care.

Data management

Data will be collected in an electronic case report form. Data will be stored on a password-protected electronic server (OpenClinica V.2.0). This is only accessible by the researchers, according to the authorisation form. Data will be analysed on completion of the study. Participants will be given an anonymous study ID to protect confidentiality, and only investigators will have access to the final trial dataset.

Statistics

Sample size

Total sample size will be 60 patients, 30 patients per group, based on a recent meta-analysis that showed a mean effect size on motor outcome after rTMS of 0.55 with a 95% CI of 0.18 (statistical programme G*power, statistical power 80%).70 71

Statistical analyses

ARAT scores will be statistically analysed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with ‘time’ (different time points before and after treatment) as within-subject factor and ‘treatment’ (real cTBS vs sham cTBS) as between-subject factor. Paired t-tests with correction for multiple comparisons will be used for post hoc analysis. Before entering the data in ANOVA, we will check for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Alternatively, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests will be used to analyse ARAT scores.

Secondary outcome parameters, that is, the additional sensorimotor function measures, disability/quality of life scores and measures of corticospinal excitability and intracortical inhibition, will be analysed in the same way as described for ARAT scores.

Statistical analysis of MRI parameters will involve repeated measures ANOVA with ‘time’ (different time points before and after treatment) as within-subject factor and ‘treatment’ (real cTBS vs sham cTBS) as between-subject factor, followed by post hoc t-testing with correction for multiple comparisons. For predictive modelling, we will employ generalised linear model-based algorithms,72 but we may also use alternative algorithms that we have recently tested on their ability to predict infarction based on multiparametric MRI.73

All patients will be included in the analyses following an intention-to-treat approach. We do not plan to perform any interim analyses.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The study has been approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

Before inclusion, patients should have read the patient information letter, which they may discuss with their relatives, to understand the goal and execution plan of the trial. After giving written informed consent patients can participate. Before the first examination, a researcher will restate the study information, and patients will (again) be informed about the possibility to ask questions about the study. Furthermore, the option to withdraw from the study at any time will be explained. If the patient is not able to write down the needed information (because of hand/arm disability), a relative can fill out the informed consent form. The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice, the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects act and the Declaration of Helsinki. All protocol changes such as modifications in eligibility criteria, outcome measures, analyses or study procedures will be submitted to the Medical Research Ethics Committee.

Safety

Adverse events are defined as any undesirable medical experience occurring to a subject during the study, whether or not considered related to cTBS. All adverse events reported spontaneously by the subject to (or observed by) the investigator or his/her staff will be recorded for the period of the treatment (2 weeks) and for an additional week after the treatment has ended. Seizures, which are the most serious rTMS-related side effect with a crude risk of approximately 0.02%,57 would only be expected to occur during or immediately after rTMS trains. Furthermore, all adverse events occurring within 24 hours after MRI will be reported. Any serious event will be immediately reported to the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

An internal Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) at the University Medical Center Utrecht has been established to perform ongoing safety surveillance. A temporary, independent project-specific member is added to the internal DSMB. The internal DSMB will monitor the progress (randomisation and losses to follow-up) and safety (evidence for significant treatment harm) aspects of the study. The internal DSMB may also advise on protocol modifications suggested by investigators or sponsors and assess impact and relevance of external evidence.

Dissemination

The results will be disseminated through (open access) peer-reviewed publications, networks of scientists, patient associations (like ‘Hersenletsel.nl’ and ‘Kennisnetwerk CVA NL’), professionals and the public, and presented at relevant conferences. Participants of the study will be updated about the progress and results of the study by newsletters. Patient engagement will be achieved by involving patients in the development of the protocol and script, for example, in improving and refining the motor task during fMRI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wilma Jentink and Annet Slabbekoorn for their input on the protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: RD conceived the study concept. RD, EvL, AV and BvdW designed the protocol. BN contributed to the conception of the protocol. EvL drafted the manuscript. All authors provided feedback throughout the development of the protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research(VICI 016.130.662).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: To promote the independent re-use of B-STARS data and to save the costs of unnecessarily compiling new datasets, access to a clean, anonymous, and well-annotated dataset will be made publicly available in a public data repository within 18 months of the final follow-up of the last patient. This will allow the B-STARS investigators sufficient time to explore the datasets, balanced by the public interest of timely access. This sharing of participant-level data will provide others the opportunity to examine new research questions and will therefore increase the impact of B-STARS.

References

- 1. Nichols-Larsen DS, Clark PC, Zeringue A, et al. Factors influencing stroke survivors' quality of life during subacute recovery. Stroke 2005;36:1480–4. 10.1161/01.STR.0000170706.13595.4f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Broeks JG, Lankhorst GJ, Rumping K, et al. The long-term outcome of arm function after stroke: results of a follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil 1999;21:357–64. 10.1080/096382899297459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol 2003;2:43–53. 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00266-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Page SJ, Sisto S, Levine P, et al. Efficacy of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in chronic stroke: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hosomi K, Morris S, Sakamoto T, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for Poststroke Upper Limb Paresis in the Subacute period. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;25:1655–64. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sunderland A, Fletcher D, Bradley L, et al. Enhanced physical therapy for arm function after stroke: a one year follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994;57:856–8 http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/doi/ 10.1136/jnnp.57.7.856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, et al. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke 2003;34:2181–6. 10.1161/01.STR.0000087172.16305.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wade DT, Langton-Hewer R, Wood VA, et al. The hemiplegic arm after stroke: measurement and recovery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1983;46:521–4. 10.1136/jnnp.46.6.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luke C, Dodd KJ, Brock K. Outcomes of the Bobath concept on upper limb recovery following stroke. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:888–98. 10.1191/0269215504cr793oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kang N, Summers JJ, Cauraugh JH. Non-Invasive brain stimulation improves Paretic Limb Force production: a Systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Stimul 2016;9:662–70. 10.1016/j.brs.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, et al. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. Stroke 1992;23:1084–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bolognini N, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Using non-invasive brain stimulation to augment motor training-induced plasticity. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2009;6:8 10.1186/1743-0003-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakayama H, Jørgensen HS, Raaschou HO, et al. Recovery of upper extremity function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:394–8. 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90161-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buma F, Kwakkel G, Ramsey N. Understanding upper limb recovery after stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2013;31:707–22. 10.3233/RNN-130332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoyer EH, Celnik PA. Understanding and enhancing motor recovery after stroke using transcranial magnetic stimulation. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2011;29:395–409. 10.3233/RNN-2011-0611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Q, Qu Y, Tao Y, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on hand function recovery and excitability of the motor cortex after stroke: a meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2014;93:422–30 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24429509 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liew SL, Santarnecchi E, Buch ER, et al. Non-invasive brain stimulation in neurorehabilitation: local and distant effects for motor recovery. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8:1–15. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simonetta-Moreau M. Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) and motor recovery after stroke. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2014;57:530–42. 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wessel MJ, Zimerman M, Hummel FC. Non-invasive brain stimulation: an interventional tool for enhancing behavioral training after stroke. Front Hum Neurosci 2015;9:265 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lefaucheur JP, André-Obadia N, Antal A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin Neurophysiol 2014;125:2150–206. 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Non-invasive brain stimulation: a new strategy to improve neurorehabilitation after stroke? Lancet Neurol 2006;5:708–12. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70525-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron 2007;55:187–99. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Di Pino G, Pellegrino G, Assenza G, et al. Modulation of brain plasticity in stroke: a novel model for neurorehabilitation. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:597–608. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muller PA, Dhamne SC, Vahabzadeh-Hagh AM, et al. Suppression of motor cortical excitability in anesthetized rats by low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. PLoS One 2014;9:e91065–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, et al. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 2005;45:201–6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Di Pino G, Pellegrino G, Assenza G, et al. Modulation of brain plasticity in stroke: a novel model for neurorehabilitation. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:597–608. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rossini PM, Burke D, Chen R, et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an I.F.C.N. Committee. Clin Neurophysiol 2015;126:1071–107. 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ackerley SJ, Stinear CM, Barber PA, et al. Priming sensorimotor cortex to enhance task-specific training after subcortical stroke. Clin Neurophysiol 2014;125:1451–8. 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Talelli P, Wallace A, Dileone M, et al. Theta burst stimulation in the rehabilitation of the upper limb: a semirandomized, placebo-controlled trial in chronic stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2012;26:976–87. 10.1177/1545968312437940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meehan SK, Dao E, Linsdell MA, et al. Continuous theta burst stimulation over the contralesional sensory and motor cortex enhances motor learning post-stroke. Neurosci Lett 2011;500:26–30. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Di Lazzaro V, Rothwell JC, Talelli P, et al. Inhibitory theta burst stimulation of affected hemisphere in chronic stroke: a proof of principle, sham-controlled study. Neurosci Lett 2013;553:148–52. 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delvaux V, Alagona G, Gérard P, et al. Post-stroke reorganization of hand motor area: a 1-year prospective follow-up with focal transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 2003;114:1217–25. 10.1016/S1388-2457(03)00070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, et al. Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke: a longitudinal fMRI study. Brain 2003;126:2476–96. 10.1093/brain/awg245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murase N, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, et al. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol 2004;55:400–9. 10.1002/ana.10848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Duque J, Hummel F, Celnik P, et al. Transcallosal inhibition in chronic subcortical stroke. Neuroimage 2005;28:940–6. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bloom JS, Hynd GW. The role of the corpus callosum in interhemispheric transfer of information: excitation or inhibition? Neuropsychol Rev 2005;15:59–71. 10.1007/s11065-005-6252-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nowak DA, Grefkes C, Ameli M, et al. Interhemispheric competition after stroke: brain stimulation to enhance recovery of function of the affected hand. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23:641–56. 10.1177/1545968309336661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grefkes C, Nowak DA, Eickhoff SB, et al. Cortical connectivity after subcortical stroke assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 2008;63:236–46. 10.1002/ana.21228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grefkes C, Fink GR. Noninvasive brain stimulation after stroke. Curr Opin Neurol 2016;29:714–20. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang WH, Kim YH, Bang OY, et al. Long-term effects of rTMS on motor recovery in patients after subacute stroke. J Rehabil Med 2010;42:758–64. 10.2340/16501977-0590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khedr EM, Etraby AE, Hemeda M, et al. Long-term effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function recovery after acute ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol Scand 2010;121:30–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huynh W, Vucic S, Krishnan AV, et al. Exploring the evolution of cortical excitability following acute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2016;30:244–57. 10.1177/1545968315593804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amengual JL, Valero-Cabré A, de las Heras MV, et al. Prognostic value of cortically induced motor evoked activity by TMS in chronic stroke: caveats from a revealing single clinical case. BMC Neurol 2012;12:35 10.1186/1471-2377-12-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ackerley SJ, Stinear CM, Barber PA, et al. Combining theta burst stimulation with training after subcortical stroke. Stroke 2010;41:1568–72. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ackerley SJ, Byblow WD, Barber PA, et al. Primed physical therapy enhances recovery of Upper Limb function in chronic Stroke Patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2016;30:339–48. 10.1177/1545968315595285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khedr EM, Ahmed MA, Fathy N, et al. Therapeutic trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation after acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2005;65:466–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173067.84247.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khedr EM, Abdel-Fadeil MR, Farghali A, et al. Role of 1 and 3 Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function recovery after acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:1323–30. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sasaki N, Mizutani S, Kakuda W, et al. Comparison of the effects of high- and low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on upper limb hemiparesis in the early phase of stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:413–8. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sasaki N, Kakuda W, Abo M. Bilateral high- and low-frequency rTMS in acute stroke patients with hemiparesis: a comparative study with unilateral high-frequency rTMS. Brain Inj 2014;28:1682–6. 10.3109/02699052.2014.947626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Conforto AB, Anjos SM, Saposnik G, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in mild to severe hemiparesis early after stroke: a proof of principle and novel approach to improve motor function. J Neurol 2012;259:1399–405. 10.1007/s00415-011-6364-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stinear CM, Barber PA, Petoe M, et al. The PREP algorithm predicts potential for upper limb recovery after stroke. Brain 2012;135:2527–35. 10.1093/brain/aws146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, et al. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120:2008–39. 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Winstein CJ, Miller JP, Blanton S, et al. Methods for a multisite randomized trial to investigate the effect of constraint-induced movement therapy in improving upper extremity function among adults recovering from a cerebrovascular stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2003;17:137–52. 10.1177/0888439003255511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goldsworthy MR, Pitcher JB, Ridding MC. A comparison of two different continuous theta burst stimulation paradigms applied to the human primary motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 2012;123:2256–63. 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee JY, Kim JW, Lee JY, et al. Is MRI a reliable tool to locate the electrode after deep brain stimulation surgery? Comparison study of CT and MRI for the localization of electrodes after DBS. Acta Neurochir 2010;152:2029–36. 10.1007/s00701-010-0779-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sauner D, Runge M, Poggenborg J, et al. Multimodal localization of electrodes in deep brain stimulation: comparison of stereotactic CT and MRI with teleradiography. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2010;88:253–8. 10.1159/000315463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, et al. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120:2008–39. 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, et al. Screening questionnaire before TMS: an update. Clin Neurophysiol 2011;122:1686 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. van der Lee JH, Roorda LD, Beckerman H, et al. Improving the Action Research Arm test: a unidimensional hierarchical scale. Clin Rehabil 2002;16:646–53. 10.1191/0269215502cr534oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Badke MB, Duncan PW. Patterns of rapid motor responses during postural adjustments when standing in healthy subjects and hemiplegic patients. Phys Ther 1983;63:13–20. 10.1093/ptj/63.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Duncan PW, Propst M, Nelson SG. Reliability of the Fugl-Meyer assessment of sensorimotor recovery following cerebrovascular accident. Phys Ther 1983;63:1606–10. 10.1093/ptj/63.10.1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oxford Grice K, Vogel KA, Le V, et al. Adult norms for a commercially available Nine Hole Peg Test for finger dexterity. Am J Occup Ther 2003;57:570–3. 10.5014/ajot.57.5.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang YC, Magasi SR, Bohannon RW, et al. Assessing dexterity function: a comparison of two alternatives for the NIH Toolbox. J Hand Ther 2011;24:313–21. 10.1016/j.jht.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bovend'Eerdt TJ, Dawes H, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Evaluation of the Modified Jebsen Test of Hand Function and the University of Maryland Arm Questionnaire for Stroke. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:195–202. 10.1191/0269215504cr722oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Houwink A, Roorda LD, Smits W, et al. Measuring upper limb capacity in patients after stroke: reliability and validity of the stroke upper limb capacity scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1418–22. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:603–12. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70495-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Duncan PW, Bode RK, Min Lai S, et al. Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: the Stroke Impact Scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:950–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 1997;27:363–70. 10.1017/S0033291796004382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hsu WY, Cheng CH, Liao KK, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor functions in patients with stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2012;43:1849–57. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.649756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wu O, Dijkhuizen RM, Sorensen AG. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of brain disorders. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2010;21:129–38. 10.1097/RMR.0b013e31821e56c2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bouts MJ, Tiebosch IA, van der Toorn A, et al. Early identification of potentially salvageable tissue with MRI-based predictive algorithms after experimental ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1075–82. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.