Abstract

Introduction

Previous literature confirms that a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) may result in long-term emotional impacts and, in vulnerable subgroups, cognitive deficits. The accurate diagnosis of mTBI and its written documentation is an important first step towards providing appropriate and timely clinical care. Surveillance studies involving emergency department (ED) and hospital-based data need to be prioritised as these provide incident mTBI estimates. This project will advance existing research findings by estimating the occurrence of mTBI among those attending an ED and quantifying the accuracy of mTBI diagnoses recorded by ED staff through a comprehensive audit of ED records.

Methods and analysis

Retrospective chart reviews (between June 2015 and June 2016) of electronic clinical records from an ED in Sydney (New South Wales, Australia) will be conducted. The study population will include persons aged 18–65 years who attended the ED with any clinical features potentially indicative of mTBI. The WHO operational criteria for the clinical identification of mTBI cases is the presence of: (1) a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 13–15 after 30 min postinjury or on presentation to hospital; (2) one or more of the following: post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) of less than 24 hours’ duration, confusion or disorientation, a witnessed loss of consciousness for ≤30 min and/or a positive CT brain scan. We estimate that 30 000 ED attendances will be screened and that a sample size of 500 cases with mTBI will be identified during this 1-year period, which will provide reliable estimates of mTBI occurrence in the ED setting.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Ethics Committee. The committee deemed this study as low risk in terms of ethical issues. The written papers from this study will be submitted for publication in quality peer-reviewed medical and health journals. Study findings will be disseminated via presentations at national/international conferences and peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: neurological injury, accident emergency and medicine, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will provide previously unavailable data on the number and proportion of patients attending the emergency department (ED) of a major metropolitan Australian hospital with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), and on the number and proportion with clear documentation of mTBI in their medical records.

Study findings may educate ED staff and/or improve clinical practice.

The current study will determine the rates of mTBI diagnosis among ED attendances only, and the findings will not be generalisable to the wider community, as it will not capture those cases treated by primary healthcare providers (eg, general practitioners) or alternatively where medical attention was not sought, which may contribute to an underestimation of population-based mTBI incidence.

As this is not a prospective study, the availability and accuracy of relevant documented clinical information in ED medical records is essential to mTBI identification in this study, and inadequacies in this information may limit conclusions about mTBI in some cases.

Introduction

A WHO review of hospital treated mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) reported an annual incidence in the range of 100–300/100 000.1 Because most mTBI is not treated in hospital, the true population incidence of mTBI has been estimated to range between 600/100 000 and 749/100 000 per year.1 2 Current literature reaffirms that mTBI may result in long-term emotional disorders,3–5 and in vulnerable subgroups, cognitive deficits.6 mTBI is now being recognised as a major health concern.7 Common postconcussive symptoms associated with but not specific to mTBI, are classified as physical (eg, headache, blurring of vision), behavioural (eg, irritability, anxiety) and cognitive (eg, difficulty with memory).3 Although postconcussive symptoms usually resolve within days or weeks, research literature indicates subjective reporting of physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms for several months or years postinjury in a subgroup of individuals.8–12 Consequences for these individuals may include reduced functional ability, heightened emotional distress and delayed return to work or school.5 13 14 However, early identification and subsequent early intervention, such as through education and support for the guided resumption of activities, significantly increases social participation and decreases the severity of postconcussive symptoms.15 The major limitation of research in this area is that mTBI cases are often underdiagnosed and thus under-reported. Not knowing the true incidence and prevalence of mTBI renders it challenging to allocate resources and inform evidence-based healthcare planning.3

Emergency department (ED) assessment is an important primary point of medical contact for early diagnosis, a key element in the management of mTBI for a significant number of patients.16–18 However, an accurate clinical identification of patients with mTBI in ED is complicated by varied criteria used for diagnosis.19–21 Furthermore, variations in diagnostic terminology and diagnostic coding make it difficult for mTBI to be identified through an administrative database.19 22–24 A prospective cohort study of all patients presenting to an urban academic ED in the USA over 6 months24 revealed inaccurate identification of patients with mTBI using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision criteria (ICD-9 codes) assigned on discharge. These ICD-9 codes were associated with a significant number of false-positive and false-negative code assignments. Powell et al 22 found that despite patients reporting symptoms consistent with an mTBI diagnosis when interviewed by study personnel, the diagnosis of mTBI was frequently absent from ED medical records. Instead, it appears the ED staff were more focused on ruling out severe brain injury for patients with a likely mechanism for TBI. This approach perhaps reflected the primary mission of the ED, that is, to stabilise and treat serious injuries, and time constraints inherent in ED practice may also have influenced findings. However, it was concluded that persons with a possible mTBI on arrival at ED were more likely not to be diagnosed.22

Moreover, Cassidy et al reported that 24% of people injured in a motor vehicle crash have a diagnosable mTBI,7 and these authors concluded mTBI to be a major health concern in the long term.7 Falls and motor vehicle crashes are leading causes of TBI; however, the true distribution of injury mechanisms for mTBI is not known. Given the lack of good-quality published studies on mTBI following motor vehicle crashes, there is an obvious gap in knowledge in this respect.3 Currently, there is limited empirical evidence as to whether persons with mTBI are accurately identified, diagnosed and recorded in Australian ED records (including in the largest state of New South Wales). The need to establish a reliable surveillance system to monitor and inform evidence-based healthcare planning and effective treatment, prevention and rehabilitation strategies for mTBI has been repeatedly emphasised.2 Consequently, this mTBI surveillance study will aim to move the research forward in this area. It will involve an electronic clinical record review employing WHO diagnostic criteria25 and secondary criteria previously used by Meares et al 26 to identify the number of patients with evidence of mTBI who were seen at an ED of a major Sydney metropolitan hospital. The study objectives are: (1) to estimate overall, age-specific and sex-specific occurrence rates of ED attendances with mTBI; (2) to assess the extent to which mTBI cases identified via chart review are explicitly identified and documented by ED staff using recorded medical diagnoses and diagnostic codes and to characterise the terminology and codes currently being used in these cases; (3) to assess the proportion of mTBI cases that occur due to falls, motor vehicle crashes or other mechanisms of injury and (4) to describe sociodemographic, injury-related and admission-related characteristics of individuals who attended ED with mTBI based on either confirmed WHO diagnostic criteria or on suggestive but insufficient/ indeterminate evidence using secondary criteria. The proposed study will clarify the nature and scope of mTBI by reporting accurate estimates of its occurrence in an ED setting as well as identifying limitations in current ED diagnosis, documentation and management (eg, assessment, discharge instructions) of mTBI. Therefore, findings from this study have the potential to improve long-term patient outcomes, inform the use of health resources and promote management consistency for the mTBI patient population.

Methods

Sample selection

The proposed study will employ a retrospective surveillance system to determine if an mTBI occurred and a diagnosis was documented by ED staff. The data source for this study will be electronic clinical records related to ED attendances with or without an associated hospital admission at Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH) over a 1-year period (between June 2015 and June 2016). RNSH is a large hospital in metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales NSW, Australia, serving a population of 213 000 inhabitants in 2016, across four local government areas. The overall number of RNSH ED attendances in the study year was approximately 80 000, and of these, 30 000 were aged 18–65 years old.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

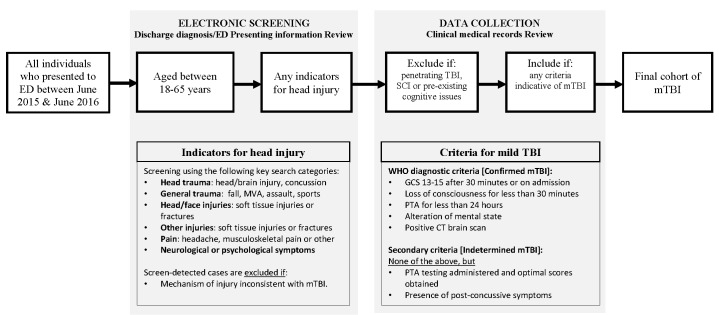

The inclusion criteria (see figure 1) are adults aged 18–65 years who presented to the ED within 24 hours postinjury with any clinical features indicative of mTBI27 based on the WHO criteria for mTBI22 25 which are: (1) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 13–15 after 30 min postinjury or on presentation to hospital; (2) at least one of the following: post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) of less than 24 hours duration, confusion or disorientation, a witnessed loss of consciousness for 30 min or less and/or positive CT brain scan indicating intracranial injuries not requiring neurosurgery.2 25 28 The exclusion criteria include: penetrating brain injury; moderate/severe TBI, spinal cord injury and pre-existing cognitive impairment.22 26 Persons who attended ED with head trauma but did not meet the WHO criteria will be classified as indeterminate mTBI if they meet one of the following secondary criteria: (1) if assessed for PTA and obtains optimal scores (ie, 18 out of 18) on the Abbreviated Westmead Post-traumatic Amnesia Scale (A-WPTAS)18 or (2) if presented to the ED for postconcussive symptoms,29 transient neurological deficits or queried loss of consciousness. Although the literature27 suggests that a diagnosis of mTBI should not be based only on postinjury symptoms, these cases may nevertheless reflect the difficulty in obtaining accurate diagnostic information (ie, WHO criteria) from ED records or the mildest injuries, where manifestations of mTBI resolve prior to the arrival of the medical personnel or presentation to hospital.26 Indeed, these cases are the most difficult to identify.

Figure 1.

Screening and data collection flow chart. Grey boxes indicate study selection process for the identification of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; MVA, motor vehicle accident; PTA, post-traumatic amnesia; SCI, spinal cord injury; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Patient screening and mTBI case identification protocol was developed with input from all investigators. Patient information will be extracted by the research team from the information management system, FirstNet, a module of the Health Electronic Medical Record that is used in New South Wales (figure 1). A limitation of FirstNet is that only a principal diagnosis can be recorded and guidelines are not explicit on whether symptoms or a diagnosis is to be entered.30 If mTBI is the diagnosis of interest, and the patient is not categorised accordingly, they will not be identified through FirstNet. To increase the accuracy of identifying possible patients with mTBI, all ED presentations meeting study age and interval period will be reviewed by a two-step process (figure 1). First, individuals with any possible indicators of mTBI as their discharge diagnosis, will be identified by the research team, using the following key search categories: (1) a diagnosis of head trauma, head injury or brain injury; (2) a mechanism of injury consistent with a possible mTBI (eg, transport-related accident, assault or fall); (3) an injury description that includes head lacerations, bruising, swelling, facial fractures or other musculoskeletal injuries or (4) mTBI-related symptoms, such as pain, neurological or behavioural symptoms. Triage presenting information will then be reviewed and the individual excluded if there is no traumatic mechanism involved or if the mechanism of injury is not consistent with mTBI.

Second, for the possible cases identified in step 1, a thorough review of all documentation available in clinical records will confirm if individuals meet the relevant WHO diagnostic criteria for mTBI. The review will also document whether alcohol and illicit drug usage was involved in the injury.18 22 26 The audit of ED records will help obtain information (if available) regarding GCS scores, with mTBI defined as a GCS score of 13–15 after 30 min postinjury or on hospital admission. Information from the A-WPTAS, a validated measure of PTA, will also be collected. The A-WPTAS scale includes eye opening, motor and verbal components from the GCS and a test of ability to recall three picture cards to measure amnesia.18 Other measures, which will be collected to confirm occurrence of mTBI include: signs of confusion or disorientation, a witnessed loss of consciousness of 30 min or less and a positive finding from brain CT scan or skull X-ray. Lastly, the presence of postconcussive symptoms is also recorded, whether in isolation (indeterminate mTBI) or in association with other indicators.

Two chart auditors (IP and KVV) have been trained in study inclusion and exclusion criteria and case identification, and pilot testing conducted to work through disagreements or differences of opinion until the two auditors arrived at a common understanding and were extracting the same cases at initial screening (per cent agreement of 91%). The first stage of the screening procedure was then assigned to KVV and the second stage to IP, so each step will be consistently undertaken by the same chart auditor. If the chart auditors are unsure about a record, all clinical evidence will be referred to and reviewed by the study investigators (BG, SM) on a weekly basis. The data will be collected using data collection sheets, and will be subsequently entered into a secure online platform, called Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).

The proposed retrospective surveillance system will also allow us to obtain sociodemographic, injury-related and admission-related data for individuals identified as having confirmed mTBI based on either WHO diagnostic criteria or suggestive, but insufficient/indeterminate evidence using secondary criteria. Variables will include: postcode, age, sex, ethnicity date of injury, mechanisms of injury (eg, motor vehicle crash, falls, sports-related) and hospital admission status.

Further, for this study, mTBI-related diagnoses (ie, brain injury, mTBI, concussion, postconcussive symptoms or syndrome) listed in the ED medical records and the assigned diagnostic codes (SNOWMED and International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes) will be collected through retrospective review to determine whether an mTBI diagnosis was or was not documented by ED staff.

Sample size

A 1-year audit of clinical and electronic ED records from RNSH will achieve substantial sample numbers. We base this assumption on a previous study by Meares (data not published), which showed that annual patient presentations to another major New South Wales ED in 2010 were 54 473, increasing in 2011 to 56 903. Meares reported in an audit of electronic and clinical medical records that between April and September 2010, there were 19 084 attendances of individuals aged between 18 and 65 years of age, and between April and September 2011, there were 20 024 attendances. The proportion identified with mTBI was 1.1% (n=228) between April and September 2010, and between April and September 2011, there were 1.3% (n=252). Therefore, for this study, we estimate that approximately 30 000 ED attendances will be screened and that 500 mTBI cases will be identified from RNSH medical records over a 1-year period. This sample size provides high precision of estimation of mTBI incidence in the ED setting (95% CIs of ±0.2% for the overall point estimate and ±1.6% for a study stratum that includes only 1% of the total sample).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure is the rate of mTBI diagnosis among ED attendances (aged 18–65 years) at RNSH over a 1-year period, based on confirmed WHO diagnostic criteria from ED records. Secondary outcomes are: (1) the proportion of mTBI cases that occurred as a result of a motor vehicle crash versus those injured in a fall or sports-related incident and (2) characterising the sociodemographic and other characteristics (eg, age, sex, ethnicity, hospital admission status) of individuals attending the ED with an mTBI diagnosis confirmed based on WHO diagnostic criteria versus suggestive but indeterminate evidence of mTBI using secondary criteria (3) characterise how mTBI diagnoses are noted and recorded by ED staff and explore the management of those injuries in the ED setting.

Data analysis plan

Demographic and clinical data will be summarised using means and SD for continuous variables and frequencies or percentages for categorical variables. Overall, age-specific and sex-specific rates of mTBI over the 1-year period will be calculated with 95% CIs. While FirstNet allows possible mTBI cases to be identified in the first instance, an audit of hospital records will allow an identification of mTBI based on meeting ≥1 of WHO criteria and/or secondary criteria. Among ED attendances identified as involving an mTBI through retrospective chart audit, the accuracy of the ED working diagnosis, documented by clinicians in the medical records, and the accuracy of diagnostic coding entered in Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms or SNOMED CT (used within hospital electronic medical records) will be examined. Further, the ICD diagnoses for inpatient admissions of mTBI will also be compared in separate analyses. Rates of agreement and misclassification will be quantified and the kappa statistic for agreement computed.

Sociodemographic, injury-related and admission-related characteristics of mTBI cases will be described. Analyses will be conducted using SPSS and/or SAS statistical software.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BG was responsible for developing the research question and led the group that secured funding. BG, IP, SM, IDC, AC, AK and MG advised on the study design and data collection. AK advised on approach to statistical analysis. IP and BG are responsible for study management and coordination, drafted the paper and will act as guarantors. All authors have read, commented on and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study is supported by the Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund. IDC is funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (reference: RESP/16/259).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Study data will be available on request to BG once the research team has completed the preplanned analyses.

References

- 1. Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Peloso PM, et al. . Incidence, risk factors and prevention of mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild traumatic brain Injury. J Rehabil Med 2004;36:28–60. 10.1080/16501960410023732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feigin VL, Theadom A, Barker-Collo S, et al. . BIONIC Study Group. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:53–64. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70262-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jagnoor J, Cameron I. Mild traumatic brain injury and motor vehicle crashes: limitations to our understanding. Injury 2015;46:1871–4. 10.1016/j.injury.2014.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stålnacke BM, Elgh E, Sojka P. One-year follow-up of mild traumatic brain injury: cognition, disability and life satisfaction of patients seeking consultation. J Rehabil Med 2007;39:405–11. 10.2340/16501977-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Craig A, Tran Y, Guest R, et al. . Psychological impact of injuries sustained in motor vehicle crashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011993 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karr JE, Areshenkoff CN, Garcia-Barrera MA. The neuropsychological outcomes of concussion: a systematic review of meta-analyses on the cognitive sequelae of mild traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 2014;28:321–36. 10.1037/neu0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Carroll LJ. Population-based, inception cohort study of the incidence, course, and prognosis of mild traumatic brain injury after motor vehicle collisions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95(3 Suppl):S278–S285. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mittenberg W, Canyock EM, Condit D, et al. . Treatment of post-concussion syndrome following mild head injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001;23:829–36. 10.1076/jcen.23.6.829.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stålnacke BM, Björnstig U, Karlsson K, et al. . One-year follow-up of mild traumatic brain injury: post-concussion symptoms, disabilities and life satisfaction in relation to serum levels of S-100B and neurone-specific enolase in acute phase. J Rehabil Med 2005;37:300–5. 10.1080/16501970510032910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Kruijk JR, Leffers P, Menheere PP, et al. . Prediction of post-traumatic complaints after mild traumatic brain injury: early symptoms and biochemical markers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:727–32. 10.1136/jnnp.73.6.727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sterr A, Herron KA, Hayward C, et al. . Are mild head injuries as mild as we think? neurobehavioral concomitants of chronic post-concussion syndrome. BMC Neurol 2006;6:7 10.1186/1471-2377-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silverberg ND, Gardner AJ, Brubacher JR, et al. . Systematic review of multivariable prognostic models for mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2015;32:517–26. 10.1089/neu.2014.3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NSW, MAAoNM. Guidelines for Mild traumatic brain Injury following a closed Head Injury, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ, et al. . Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:714–48. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dikmen S, McLean A, Temkin N. Neuropsychological and psychosocial consequences of minor head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986;49:1227–32. 10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bazarian J, Hartman M, Delahunta E. Minor head injury: predicting follow-up after discharge from the Emergency Department. Brain Inj 2000;14:285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bazarian JJ, McClung J, Cheng YT, et al. . Emergency department management of mild traumatic brain injury in the USA. Emerg Med J 2005;22:473–7. 10.1136/emj.2004.019273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meares S, Shores EA, Taylor AJ, et al. . Validation of the Abbreviated Westmead Post-traumatic Amnesia Scale: a brief measure to identify acute cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2011;25:1198–205. 10.3109/02699052.2011.608213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blostein P, Jones SJ. Identification and evaluation of patients with mild traumatic brain injury: results of a national survey of level I trauma centers. J Trauma 2003;55:450–3. 10.1097/01.TA.0000038545.24879.4D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruff RM, Jurica P. In search of a unified definition for mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1999;13:943–52. 10.1080/026990599120963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Esselman PC, Uomoto JM. Classification of the spectrum of mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1995;9:417–24. 10.3109/02699059509005782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Powell JM, Ferraro JV, Dikmen SS, et al. . Accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury diagnosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1550–5. 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tellier A, Della Malva LC, Cwinn A, et al. . Mild head injury: a misnomer. Brain Inj 1999;13:463–75. 10.1080/026990599121386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bazarian JJ, Veazie P, Mookerjee S, et al. . Accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury case ascertainment using ICD-9 codes. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:31–8. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb00981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Holm L, et al. . Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the who collaborating centre task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med 2004;36:113–25. 10.1080/16501960410023877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meares S, Shores EA, Smyth T, et al. . Identifying posttraumatic amnesia in individuals with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15 after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:956–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, et al. . Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2009;24:3–10. 10.1093/arclin/acp006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Peloso PM, et al. . Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild traumatic brain Injury. J Rehabil Med 2004:84–105. 10.1080/16501960410023859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoffer ME, Szczupak M, Kiderman A, et al. . Neurosensory Symptom Complexes after acute mild traumatic brain Injury. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146039 10.1371/journal.pone.0146039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liaw ST, Chen HY, Maneze D, et al. . The Quality of Routinely Collected Data: using the "Principal Diagnosis" in Emergency Department Databases as an Example. Electro J Health Info 2012;7:e1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.