Abstract

Background

The use of telehealth steadily increases as it has become a viable modality to patient care. Early adopters attempt to use telehealth to deliver high-quality care. Patient satisfaction is a key indicator of how well the telemedicine modality met patient expectations.

Objective

The objective of this systematic review and narrative analysis is to explore the association of telehealth and patient satisfaction in regards to effectiveness and efficiency.

Methods

Boolean expressions between keywords created a complex search string. Variations of this string were used in Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature and MEDLINE.

Results

2193 articles were filtered and assessed for suitability (n=44). Factors relating to effectiveness and efficiency were identified using consensus. The factors listed most often were improved outcomes (20%), preferred modality (10%), ease of use (9%), low cost 8%), improved communication (8%) and decreased travel time (7%), which in total accounted for 61% of occurrences.

Conclusion

This review identified a variety of factors of association between telehealth and patient satisfaction. Knowledge of these factors could help implementers to match interventions as solutions to specific problems.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, telehealth, telemedicine, quality, access, patient quality, telecommunications, home telehealth.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Inserting technology into a medical intervention should not be without deliberate design. This review serves as a voice of the patient to help guard against the implementation of technology merely for its convenience or shiny appeal.

This study uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis standard, which is an internationally recognised protocol for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews that increases the validity of the results.

A group >30 selected from Medical Subject Headings key terms indexed through established research databases increases the reliability of the review.

Published studies do not often clearly set out reasons for inserting technology into an intervention, and therefore, it is not clear whether the patient satisfaction observed was congruent with the change of intervention.

Telehealth, in general, is a relatively new topic in medicine (since the 1990s) so inferences that result from studies are difficult to compare to older, more traditional interventions.

Introduction

Rationale

The mental image of medical house calls is one of archaic practices in small towns and otherwise rural communities, or something associated with concierge medicine. However, telehealth brings the doctor back into the patient's home. Healthcare has begun transitioning to more technological-delivered services, making it possible to receive healthcare services from the comfort of one's home, without driving to the clinic, or frustratingly trying to find a parking spot before one's appointment. This review examines telehealth and any association it might have with patient satisfaction.

This review uses the definition of telehealth from WHO:

The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies, for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, in all the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.1

Following WHO's example, we did not distinguish between telehealth and telemedicine; instead we used the term telehealth to address both telehealth and telemedicine.1 This broad definition of telehealth encompasses several modes of delivery, such as videoconferencing, mobile applications and secure messaging. WHO recognises several branches of telemedicine: teleradiology, teledermatology, telepathology and telepsychology.1 With the increased use of technology in healthcare, there has been a great emphasis on telehealth because it can extend the services of providers to remote locations and capitalise on the availability of subject matter experts and overcome the barrier of proximity. Telehealth extends access, and it has the potential of making healthcare services more convenient for patients, especially those in rural areas, those with small children (child care) and those with mobility restrictions.2 3

Patient satisfaction is a growing concern in all aspects of healthcare, and as the voice of the customer, it is a measure of quality that is published in the USA through its Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, and it can be tied to reimbursements from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid through results of Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. As with traditional modalities of healthcare delivery, telehealth relies heavily on reports of patient satisfaction because the patients are the only source of information that can report how they were treated and if the treatment received met the patients’ expectations of care.4 5 If the patients are not happy with their healthcare services being provided remotely, the service becomes redundant and expensive. With the increase in prevalence of telehealth, it is important to maintain the key quality indicator of patient satisfaction regardless of modality of delivery. The voice of the customer needs to be continuously heard so that telehealth developers can exercise agility in the development process while the healthcare organisation continues to develop more technology-based care that meets the needs of patients and providers. The technology base inherent to telehealth dramatically changes the mode of delivery, but a strong patient-to-provider relationship must be maintained independent of the modality. A definition of patient satisfaction, effectiveness and efficiency is provided at the end of the article.

Objective

We had multiple research questions. R1: Is there an association of telehealth with patient satisfaction? R2: Are there common facilitators of either efficiency or effectiveness mentioned in the literature that would provide a positive or negative association between telehealth and patient satisfaction?

Methods

Information sources, search and study selection

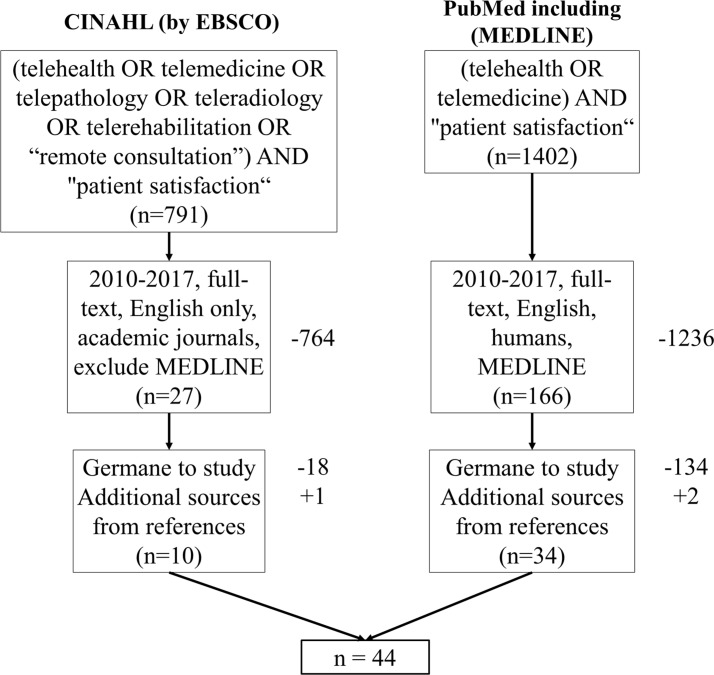

The two sources of data were the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCOhost and PubMed (MEDLINE). We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis as our basis of organisation.6 We used a variety of key search terms, as listed in the Medical Subject Headings combined with Boolean operators. Search terms were adapted for use in the different databases. Details for each database are provided as onlinesupplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2017-016242supp001.pdf (8.3KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria were 2010–2017, English only, full text available and human research. We also filtered for all but academic publications (peer-reviewed in CINAHL) and in CINAHL we excluded MEDLINE to eliminate the duplicates already captured in PubMed. Instead of including reviews in the analysis, two reviews on a similar topic were earmarked for later comparison with our own results. Abstracts were reviewed for suitability based on our research concept that included both telehealth and some assessment of patient satisfaction.

Data collection process

A flow chart of our data collection process is located as online.supplementary material. Before reviewing abstracts for suitability to our objective, we agreed to look for articles that included telehealth and some measure of patient satisfaction. Articles were assessed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Discussion sessions and consensus meetings were held to increase the inter-rater reliability of the group as they conducted the screening and analysis. During the consensus meetings, factors and themes were identified through observation and discussion; for example, as we discussed the articles, it became evident that patient satisfaction was often stated in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, so these became the themes.

bmjopen-2017-016242supp002.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)

Standard systematic review procedures were followed to control for selection bias and ensure our search was exhaustive.

Reviewers compiled their notes on patient satisfaction, effectiveness and efficiency in a literature matrix. Another consensus meeting was conducted to discuss findings and make inferences. During the consensus meeting, individual observations were discussed and combined into similar groupings throughout the sample to simplify our assessment of associations. This is a form of narrative analysis and sensemaking.7 Observations of effectiveness and efficiency were combined and sorted into an affinity matrix for final analysis.

Data items and summary measures

Our litmus test was to include articles that included a combination of telehealth and patient satisfaction, and a measure or assessment of effectiveness or efficiency. We eliminated those that fell short of those goals.

Risk of bias in individual studies and risk of bias across studies

Bias was discussed during consensus meetings. The consensus meetings served as a control on our own selection bias and selective reporting within studies.

Summary measures and synthesis of results

Our review examines articles that combine telehealth intervention with patient satisfaction and include some mention of effectiveness or efficiency. A physical count of these observations was made. After all observations were combined into an Excel file, and after all observations were condensed into themes of effectiveness or efficiency, all themes were displayed in an affinity matrix to identify the number of occurrences of each theme. These were sorted by frequency.

Results

Study selection, study characteristics and results of individual studies

Our search process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search process with inclusion and exclusion criteria. CINAHL, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

After the initial search yielded 2193 results, 193 underwent abstract and then full-text review resulting in 44 papers being included in the study.

Table 1 lists a summary of our analysis and observations from our team (n=44). For every article/study in the sample, we made observations for satisfied, which was a screening criteria, and effective and efficient. Studies are listed in order of publication with the most recent at the top. The reference numbers correspond to those in the references section.

Table 1.

Compilation of observations for our sample

| Date | Author | Title | Journal | Summary/relevance | Technology used | Potential bias, sample size, miscellaneous comments |

| April 2017 | Schulz-Heik et al 8 | Results from a clinical yoga program for veterans via telehealth provides comparable satisfaction and health improvements to in-person yoga. | BMC Complement Altern Med | Clinical yoga with US Veterans Affairs population | Videoconferencing | VA population in Palo Alto only (geographically limited), acceptable sample size (n=29 control, n=30 intervention) |

| January 2016 | Iqbal et al 9 | Cost effectiveness of a novel attempt to reduce readmission after ileostomy creation | JSLS | Patient satisfaction: satisfaction scored 4.69 out of 5 Effective: hospital readmission rates decreased $63 821 (71%) (p=0.002) | Telephone call (daily) for 3 weeks after discharge | Limited to one area of the country and beneficiaries to University of Florida health system (geographically limited), good sample size (n=23 preintervention, n=32 postintervention) |

| May 2016 | Muller et al 10 | Acceptability, feasibility, and cost of telemedicine for nonacute headaches: a randomized study comparing video and traditional consultations | J Med Internet Res | Used telehealth to diagnose and treat non-acute headaches Satisfaction: patients satisfied with video and sound quality Efficient: median travel distance for rural patients was 7.8 hours, cost €249, lost income €234 per visit (saved) Effective: intervention group's consultations were shorter than control group |

Videoconferencing | Non-acute headache patients from Northern Norway, strong sample size (n=200), participants randomised |

| April 2016 | Dias et al 11 | Voice telerehabilitation in Parkinson's disease | Codas | Satisfaction: reported as high Effective: preference for telehealth intervention |

Videoconference and telephone | 85% male (gender bias), videoconferencing mimicked the face-to-face rehabilitation for Parkinson's patients, small sample size (n=20) |

| November 2016 | Langabeer et al 12 | Telehealth-enabled emergency medical services program reduces ambulance transport to urban emergency departments | West J Emerg Med | Satisfaction: no decrease Efficient: 56% reduction in ambulance transports and 53% decrease in response time for the intervention group than the control |

Telephone | Limited to patients regional to Houston, Texas (geographically limited), no randomisation, strong sample size (n=5570) |

| 2016 | Hoaas et al 13 | Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods study | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making | Satisfaction: generally highly satisfied Effective: increased health benefits, self-efficacy, independence, emotional safety and maintenance of motivation |

Webpage for daily telemonitoring and self-care and weekly follow-up videoconference consults with a physiotherapist | Remote population of northern Norway, small sample size (n=10) |

| 2016 | Jacobs et al 14 | Patientsatisfaction with a teleradiology service in general practice | BMC Family Practice | Satisfaction: island residents, the elderly and those with no history of trauma were more satisfied with the technical and interpersonal aspects of the teleconsultation than non-residents, younger patients and those with history of trauma | Teleradiology | Restricted to rural health and Netherlands (geographically limited), strong sample (n=381) |

| February 2017 | Bradbury et al 15 | Utilizing remote real-time videoconferencing to expand access to cancer genetic services in community practices: A multicenter feasibility study | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Satisfaction: all patients reported satisfaction and knowledge increased significantly Effective: general anxiety and depression decreased |

Videoconferencing | Restricted to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (geographically limited), good sample size (n=41) |

| January 2016 | AlAzab and Khader16 | Telenephrology application in rural and remote areas of Jordan: benefits and impact on quality of life | Rural and Remote Health | Satisfaction: patient satisfaction mean=96.8 Effective: mean SF8 score increased significantly (physical components of quality of life) |

Electronic monitoring and telephone calls | Rural health (geographically limited), strong sample size (n=64) |

| March 2016 | Fields et al 17 | Remote ambulatory management of veterans with obstructive sleep apnea | Sleep | Satisfaction: no difference in functional outcomes, patient satisfaction, dropout rates or objectively measured PAP adherence Effective: telemedicine participants showed greater improvement in mental health scores and their feedback was positive |

Telemonitoring and telephone follow-up calls | Restricted to veterans in the Philadelphia area (geographically limited), good sample size (n=60) |

| January 2016 | Georgsson and Staggers18 | Quantifying usability: an evaluation of a diabetes mHealth system on effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction metrics with association user characteristics in the US and Sweden | Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association | Satisfaction: good Effective: good but not excellent usability |

mHealth application | Younger patients with more experience with information technology scored higher than others (age and technology bias), small sample size (n=10) |

| March 2016 | Polinski et al 19 | Patients' satisfaction with and preference for telehealth visits | Journal of General Internal Medicine | Satisfaction: 33% preferred telehealth visits to traditional in-person visits; women preferred telehealth visits Efficient: telehealth increased access to care. Lack of insurance increased odds of preferring telehealth Efficient: other positive predictors were quality of care received, telehealth convenience and understanding of telehealth |

Videoconferencing at Minute Clinics with diagnostic tools operated by a nurse | 70% women (gender bias), test was conducted in California and Texas (convenience sample), strong sample (n=1734) |

| 2015 | Levy et al 20 | Effects of physical therapy delivery via home video telerehabilitation on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes | Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development | Satisfied: all but one participant reported satisfied or highly satisfied Effective: participants demonstrated significant improvement in most outcomes measures Efficient: participants avoided 2,774.7 =/– 3197.4 travel miles, 46.3±53.3 hours or driving time, and $1151.50 ± $1326.90 in travel reimbursement |

Videoconferencing | Convenience sample, 92% male (gender bias), 69% >64 years (age bias), US Veterans only, small sample (n=26) |

| 2014 | Holmes and Clark21 | Technology-enabled care services: novel method of managing liver disease | Gastrointestinal Nursing | Satisfied: high, patients liked the self-manage aspect Effective: participants lost weight, outcomes improved, readmissions decreased from 12 to 4 Efficient: average cost per patient 68.86 British pounds |

Remote monitoring and text messaging | Small sample size (n=12) |

| 2015 | Levy et al 22 | The Mobile Insulin Titration Intervention (MITI) for insulin glargine titration in an urban, low-income population: randomized controlled trial protocol | JMIR Research Protocols | Highly satisfied: patientsin the intervention group reported higher levels of satisfaction Effective: significantly more in the intervention group had reached their optimal insulin levels |

Mobile Insulin Titration Intervention | True experiment (randomised, good sampling technique) |

| 2015 | Moin et al 23 | Women veterans’ experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Effective: improved behavioural outcomes, more appropriate for women Satisfied: participants felt empowered and accountable, they felt it was convenient and a good fit with their health needs and lifestyle |

Web-based | Women veterans, computer literacy was an issue for some (gender bias), small sample size (n=17) |

| 2015 | Cotrell et al 24 | Patient and professional user experiences of simple telehealth for hypertension, medication reminders and smoking cessation: a service evaluation | BMJ Open | Satisfied: positive patient satisfaction indicators Effective: improvements were made over Florence, and users took an active approach to achieve their goals, patients felt empowered |

Telemonitoring and medication reminders | Satisfaction with the service appeared optimal when patients were carefully selected (selection bias), strong sample (n=1707) |

| 2014 | Tabak et al 25 | A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial | International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Satisfied: satisfaction was higher with the control group than the telehealth group Effective: better clinical measures in the telehealth group |

Web-based and smartphone application with an activity coach | Strong study design, small sample size (n=19) |

| 2014 | Kim et al 26 | Costs of multidisciplinary parenteral nutrition care provided at a distance via mobile tablets | Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition | Satisfied: easy to use, very convenient Effective: outcomes similar to in-clinic visits Efficient: cost $916.64 per patient |

Telephone with semistructured interviews | Good sample size (n=20 visits for 45 patients) |

| 2014 | Cancela et al 27 | Wearability assessment of a wearable system for Parkinson's disease remote monitoring based on a body area networkof sensors | Sensors | Satisfied: overall satisfaction high, but some concern over public perceptions about the wearable sensors Effective: for remote monitoring, wearable systems are highly effective |

Remote monitoring based on a body area networkof sensors | An extension of the Body Area Network sensors (limited population), good sample size (n=32) |

| 2014 | Casey et al 28 | Patients' experiences of using a smartphone application to increase physical activity: the SMART MOVE qualitative study in primary care | Br J Gen Pract | Satisfied: good usability Effective: transformed relationships with exercise |

Smartphone application | Small sample size (n=12) |

| January 2014 | Tsai et al 29 | Influences of satisfaction with telecare and family trust in older Taiwanese people | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Satisfied: user satisfaction very high Effective: user perception of high quality |

Telemonitoring, web-based, telephone | Focus was on older users and their families, convenience sample, good size (n=60) |

| 2014 | Oliveira et al 30 | Telemedicine in Alentejo | Telemedicine and e-Health | Satisfied: positive impact on patient experience Efficient: average time and cost of a tele-appointment is 93 min for teleconsultation and 9.31 pounds versus 190 min and 25.32 pounds for a face-to-face |

Telephone | Participants are older and less educated than the rest of the population of Portugal (age and education bias) |

| 2013 | Minatodani et al 31 | Home telehealth: facilitators, barriers, and impact of nurse support among high-risk dialysis patients | Telemedicine and e-Health | Satisfaction: patients reported high levels of satisfaction with RCN support because of the feedback on identification of changes in their health status, enhanced accountability, self-efficacy and motivation to make health behaviourchanges Effective: through telehealth, greater self-awareness, self-efficacy and accountability Efficient: feedback was more efficient |

Telemonitoring with nurse support | Limited population, good sample size (n=33) |

| 2013 | Akter et al 32 | Modelling the impact of mHealth service quality on satisfaction, continuance and quality of life | Behaviour & Information Technology | Satisfied: satisfaction is related to service quality, continuance intentions and quality of life Effective: mHealth should deliver higher-order, societal outcomes |

Smartphone application | Selection bias |

| 2014 | Hung et al 33 | Patient satisfaction with nutrition services amongst cancer patients treated with autologous stem cell transplantation: a comparison of usual and extended care | Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics | Satisfied: higher use was indicative of higher satisfaction Effective: higher use was clinically important to outcomes |

Telephone | Small sample size (n=18) |

| December 2015 | Buis et al 34 | Use of a text message program to raise type 2 diabetes risk awareness and promote health behavior change (part II): assessment of participants' perceptions on efficacy | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Satisfied: 67.1% reported very high satisfaction Effective: txt4health messages were clear, increased disease literacy and more conscious of diet and exercise Efficient: low participant costs |

Text messaging | Michigan and Cincinnati only (geographically limited), strong sample (n=159) |

| 2013 | Houser et al 35 | Telephone follow-up in primary care: can interactive voice responsecalls work | Studies in Health Technology and Informatics | Satisfied: strong satisfaction reported for the interactive voice response system, IVRS Effective: patients felt informed |

Telephone | Small sample of those who received the call IVRS, small sample size (n=19) |

| 2013 | Kairy et al 36 | The patient's perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Satisfied: feeling an ongoing sense of support Effective: tailored challenging programmes using telerehabilitation Efficient: improved access to services with reduced need for transportation, easy to use |

Videoconferencing | Convenience sample, single case, small sample size (n=6) |

| 2013 | Bishop et al 37 | Electronic communication improves access, but barriers to its widespread adoption remain | Health Affairs | Satisfied: easier access to and better communication with provider Effective: patients with repeat issues of a condition are able to reset the treatment for the most recent episode Efficient: it takes about 1 min per email, and it improves the efficiency of an office visit |

Email and videoconferencing | New York City only, strong resistance to change cited (geographically limited), strong sample (n=630) |

| 2013 | Pietta et al 38 | Spanish-speaking patients' engagement in interactive voice response (IVR) support calls for chronic disease self-management: data from three countries | Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare | Satisfied: 88% patients reported ‘very satisfied’, 11% ‘mostly satisfied’ Effective: 100% patients felt the interactive voice response: IVR were helpful, 77% reported improved diet, 80% reported improved symptom monitoring, 80% reported improved medication adherence |

Telephone | 73% women, average 6.1 years of education (age and education bias), strong sample (n=268) |

| 2013 | Gund et al 39 | A randomized controlled study about the use of eHealth in the home health care of premature infants | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making | Satisfied: parents felt that the Skype calls were better than regular follow-up, and it often replaced an in-home visit Effective: same or better outcomes because the parents did not have to bring infants in Efficient: Nurses took <10 min of work time daily to answer questions |

Videoconferencing | Randomisation used Semistructured interviews were only used for 16 families, small samples (n=13, 12, 9) |

| 2013 | ter Huurne et al 40 | Web-based treatment program using intensive therapeutic contact for patients with eating disorders: before-after study | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Satisfied: high satisfaction Effective: significant improvements in eating disorder psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, quality of life, and physical and mental health; body mass index improved for obesity group only Efficient: task completion rate was 80% for the younger group and 64.6% for the older group |

Web-based | Not all participants reported the same diagnoses, strong pre–post design, strong sample (n=89) |

| 2012 | Chun and Patterson41 | A usability gap between older adults and younger adults on interface design of an Internet-based telemedicine system | Work | Satisfied: on a seven-point scale, satisfaction scores were 3.41 younger and 3.54 older, although there was equal dissatisfaction with the design of the system | Web-based | Small sample size (n=16) |

| 2012 | Lee et al 42 | The VISYTER Telerehabilitation system for globalizing physical therapy consultation: issues and challenges for telehealth implementation | Journal of Physical Therapy Education | Satisfied: reported as high and very high Effective: increases access where proximity is an issue Efficient: links multiple providers together for teleconsultation |

Videoconferencing | Limited scope for conclusions, patients in Mexico, providers in the USA (cultural bias), small sample (n=3) |

| 2012 | Saifu et al 43 | Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics | The American Journal of Managed Care | Satisfied: 95% reported highest level of satisfaction Effective: 95% reported a preference for telemedicine versus in-person visit Efficient: reported a significant reduction in health visit-related time, mostly due to decreased travel |

Videoconferencing | Veterans in Los Angeles, California, only, convenience sample (geographically limited), strong sample (n=43) |

| 2012 | Lua and Neni44 | Feasibility and acceptability of mobile epilepsy educational system (MEES) for people with epilepsy in Malaysia | Telemedicine and e-Health | Satisfied: 74% reported very or quite useful Effective: excellent modality for education, drug-taking reminder and clinic appointment reminder |

Text messaging | Good mix of genders, homo-ethnic sample: 92.2% Malay (racial bias), median age 25 (age and technology bias— younger may already be more receptive to technology), good size sample (n=51) |

| 2012 | Finkelstein et al 45 | Development of a remote monitoring satisfaction survey and its use in a clinical trial with lung transplant recipients | Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare | Satisfied: 90% of the subjects were satisfied with the home health telehealth service Effective: frequency of communication increased |

Remote monitoring | Limited population |

| 2011 | Gibson et al 46 | Conversations on telemental health: listening to remote and rural First Nations communities | Rural and Remote Health | Satisfied: 47% positive response, 21% neutral, 32% negative Effective: increased comfort in the therapeutic situation, increased usefulness Efficient: increased access to services |

Videoconferencing | First-nations communities only (limited population), strong sample (n=59) |

| 2010 | Doorenbos et al 47 | Satisfaction with telehealth for cancer support groups in rural American Indian and Alaska Native communities | Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing | Satisfied: participants reported high levels of satisfaction with support groups via videoconference Effective: results of this descriptive study are consistent with other research that shows the need for support groups as part of overall therapy for cancer survivors |

Voice teleconference for group meetings | All participants were women (gender bias), rural care only, participants were members of American Indian or Alaskan Native (limited population), strong sample size (n=900) |

| 2010 | Breen et al 48 | Formative evaluation of a telemedicine model for delivering clinical neurophysiology services part II: the referring clinician and patient perspective | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making | Satisfied: teleneurophysiology improved satisfaction with waiting times, availability of results and impact on patient management Effective: telephysiology and control groups were equally as anxious about their procedure, telephysiology can improve access to CN services and expert opinion Efficient: reduced travel burden and need for overnight journeys |

Teleneurophysiology which included an EEG | Remote-rural population of Northern Ireland, small sample of physicians (n=9 physicians, 116 patients) |

| 2010 | Everett and Kerr49 | Telehealth as adjunctive therapy in insulin pump treated patients: a pilot study | Practical Diabetes International | Satisfied: patients reported more understanding, insight and control by viewing data and easy access to health professional Effective: intervention group demonstrated improved diabetes control Efficient: health professional time was <10 min each day to review data and was incorporated into current workload |

Telemonitoring and text messaging | Each user's home was visited to set up and demonstrate the system (good control for validity), small sample (n=16) |

| 2010 | Gardner-Bonneau50 | Remote patient monitoring: a human factors assessment | Human Factors Horizons | Satisfied: the intervention device was intuitive to use Effective: telehealth group showed clinical improvements Efficient: economic analysis showed savings in the COPD telemonitoring group, software issues caused many interventions by medical staff which consumed time |

Remote monitoring | Medical literacy became an issue when the device asked patients if their readings were normal, small sample size (n=27 control, n=19 intervention) |

| 2010 | Shein et al 51 | Patient satisfaction with Telerehabilitation assessments for wheeled mobility and seating | Assistive Technology | Satisfied: higher satisfaction with telerehabilitation Efficient: great time savings in travel |

Videoconferencing | 89.6% Caucasian, average age was 55, (racial and age bias), good sample (n=32) |

CN, Clinical Neurophysiology; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IVRS, Interactive Voice Response System; PAP, Positive Airways Pressure; RCN, Remote Care Nurse; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Synthesis of results

We analysed the way 44 articles reported patient satisfaction.8–51 In tota, 248 9 11 13 15–18 21–25 27–29 32 33 35 38 40 44 45 47 studies reported patient views on effectiveness, 610 12 14 30 41 51 studies reported patient satisfaction and 1419 20 26 31 34 36 37 39 42 43 46 48–50 studies reported both. The third column lists comments and details that could point to selection bias. Potential risk of bias among papers included no randomisation,12 small sample size,11 13 18 21 23 25 28 33 35 36 41 48 50 limited population,15 20 27 29 31 45–47 gender bias,19 20 23 38 47 technology bias,18 23 44 50 selection bias,24 32 38 geographically limited,8 9 12 14 16 17 34 37 43 age bias,20 29 30 38 44 51 education bias30 38 and racial bias.44 51

Additional analysis

Table 2 outlines the frequency with which different factors were raised among the included paper. Through a narrative analysis we identified commonalities among the various studies (19 factors) and compiled them into an affinity matrix to show frequency of occurrence. The matrix is sorted by frequency of occurrence.

Table 2.

Affinity matrix

| Factor | Article reference number | Frequency |

| Improved outcomes | 8 9 11 13 15–18 20–26 31–33 38–41 47 50 | 24 |

| Preferred modality | 8 9 11 14 15 19 22 26 34 43 44 46 | 12 |

| Ease of use | 18 19 23 26 28 36–38 46 49 50 | 11 |

| Low cost or cost savings | 10 14 16 20 21 23 26 34 50 | 9 |

| Improved communication | 24 27 31 36 37 39 42 45 49 | 9 |

| Travel time | 10 12 20 30 36 43 48 51 | 8 |

| Improved self-management | 13 21 23 28 31 32 48 | 7 |

| Quality | 16 19 29 32 40 | 5 |

| Increased access | 19 42 46 48 | 4 |

| Increased self-awareness | 31 34 35 38 | 4 |

| Decreased wait times | 16 43 48 49 | 4 |

| Fewer miles driven | 10 14 20 51 | 4 |

| Decreased in-person visits | 12 39 43 | 3 |

| Improved self-efficacy | 13 23 31 | 3 |

| Good modality for education | 15 34 44 | 3 |

| Low time to manage | 37 39 49 | 3 |

| Improved medication adherence | 13 38 44 | 3 |

| Decreased readmissions | 9 21 | 2 |

| Fewer missed appointments | 44 | 1 |

| 119 |

We acknowledge that frequency of occurrence does not equate to importance, but it has been used in other literature reviews as simply an issue of probability.52–54 Five factors were mentioned in the literature 65/119 occurrences (55%): improved outcomes,8 9 11 13 15–18 20–26 31–33 38–41 47 50 preferred modality, 8 9 11 14 15 19 22 26 34 43 44 46 ease of use,18 19 23 26 28 36–38 46 49 50 low cost or cost savings, 10 14 16 20 21 23 26 34 50 and improved communication.24 27 31 36 37 39 42 45 49

Discussion

Summary of evidence

Telehealth has the potential to extend the boundaries of providers’ practices by overcoming the barrier of proximity. Along with the introduction of a new modality of care comes change, and the literature mentioned various reactions to this change. One study identified heavy resistance to change,29 37 while others mentioned an embrace of the change.29 48 Older patients, in general, do not embrace change, but recent studies have identified a generational acceptance of technology and mHealth in general.55

Our findings from this systematic review and narrative analysis identify some issues that are salient in the literature. To help overcome provider resistance to change to telehealth, it should be noted that over the last 7 years 20% of the factors of effectiveness in the literature were improved outcomes. Providers and patients should embrace telehealth modalities because of its ease of use,18 19 23 26 28 36–38 46 49 50 its tendency to improve outcomes8 9 11 13 15–18 20–26 31–33 38–41 47 50 and communication,24 27 31 36 37 39 42 45 49 and its low cost.10 14 16 20 21 23 26 34 50 It can decrease travel time10 12 20 30 36 43 48 51 and increase communication with providers. Telehealth can provide a high-quality service, increase access to care,19 42 46 48 increase self-awareness31 34 35 38 and item powers patients to manage their chronic conditions.13 21 23 28 31 32 48 Healthcare organisations should embrace telehealth because it decreases missed appointments,44 is a good modality for education,15 34 44 decreases wait times,16 43 48 49 decreases readmissions9 21 and improves medication adherence.13 38 44 But most importantly, policymakers need to help legislation catch up with the technology by enabling additional means of reimbursement for telehealth because the modality improves outcomes,8 9 11 13 15–18 20–26 31–33 38–41 47 50 which improves public health.

Comparison

The results of our review and narrative analysis are consistent with other reviews. Health outcomes have been identified as a factor of effectiveness in chronically ill patients in multiple studies.56 Improvements have been identified for both physical and behavioural conditions. The review by de Jong et al, did not identify a significant decrease in use.56 This review also focused on interventions that used asynchronous communication, like email and text messages, with an older population. Our study included both asynchronous and synchronous interventions with all ages.

We were able to locate a study from 2011 that also evaluated telehealth and patient satisfaction.57 The researchers used secondary data analysis as the basis for their study. Their study focused on patient satisfaction and home telehealth in US Veterans. Similar to the de Jong review, this study focused on an older population ranging from 55 to 87, while our analysis included younger age groups. Its focus on US Veterans while ours included this group as only part of our population. Our approach can equate to a greater external validity to our analysis. The Young et al review found that its participants were extremely satisfied with the care coordination/home telehealth programme. The US Veterans in this review embraced the new modality. The researchers found a decrease in use associated with the telehealth modality.

Limitations

We identified several limitations in the conduct of our literature review and narrative analysis. Selection bias is possible within this study; however, our group consensus methods will have mitigated against this risk. Publication bias is another risk, particularly as we did not extend our search to the grey literature. Limiting our search to only two databases could easily have omitted valid articles for our review. We controlled for inter-rater reliability through the initial focus study of the topic followed by several consensus meetings held along the iterative process. By continuing to review our findings, we follow the example of other reviews and narrative analyses.52–55

The final limitation that we identified was the young age of the telehealth modality of care. It has existed since the early 1990s, but compared with traditional medicine, it is quite young. Because it is technologically based, we chose to only look at the last five years, which could also limit our findings, but the rapid advancement of a technologically based modality drives a more recent sample to make current observations and conclusions.

Conclusions

Overall, it was found that patient satisfaction can be associated with the modality of telehealth, but factors of effectiveness and efficiency are mixed. We found that patients’ expectations were met when providers delivered healthcare via videoconference or any other telehealth method. Telehealth is a feasible option for providers who want to expand their practices to remote areas without having to relocate or expand their footprint of their practice. As telehealth continues to be developed, special care should be given to incorporate features that enable acceptance and reimbursement of this modality.

Basic definitions

Patient satisfaction: The U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services defines this term as the patient's perspective of care which can be objective and meaningful to create comparisons of hospitals and other healthcare organisations.58

Effective: Successful or achieving the results that you want.59 Usually associated with outcomes.

Efficient: Performing or functi8oning in the best possible manner with the least waste of time and effort; having and using requisite knowledge, skill and industry.60

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Texas State University for using their library database for their research.

Footnotes

Contributors: CK directed the initial research, served as lead author, mediated discussions about the merit of abstracts/articles, integrated the input from all team members and helped refine the figure and tables to provide continuity and flow. NK contributed the initial draft of the introduction and integrated her viewpoints into the methods, discussion and worked with JV on the in-text citations. BR contributed the initial draft of the abstract and integrated her viewpoints into the methods, discussion (benefits). LT created the initial draft of figure 1 (literature review process) and the initial draft of benefits and barriers charts. JV integrated her viewpoints into the methods, the initial draft of the discussion (barriers) section and worked with NK on the in-text citations. MB served as an expert in research in U.S. Veterans due to his research in this area, and he contributed meaningful contribution to the formation of analysis and conclusion.

Competing interests: None declared

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are freely available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in Member States: report on the second global survey on eHealth: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finkelstein SM, Speedie SM, Potthoff S, et al. . Home telehealth improves clinical outcomes at lower cost for home healthcare. Telemed J E Health 2006;12:128–36. 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rojas SV, Gagnon MP. A systematic review of the key indicators for assessing telehomecare cost-effectiveness. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:896–904. 10.1089/tmj.2008.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cleary PD. A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:33–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LaBarbera PA, Mazursky D. A Longitudinal Assessment of Consumer satisfaction/Dissatisfaction: the Dynamic Aspect of the Cognitive process. Journal of Marketing Research 1983;20:393–404. 10.2307/3151443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kohler C. Narrative analysis . 30, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schulz-Heik RJ, Meyer H, Mahoney L, et al. . Results from a clinical yoga program for veterans: yoga via telehealth provides comparable satisfaction and health improvements to in-person yoga. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:198 10.1186/s12906-017-1705-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iqbal A, Raza A, Huang E, et al. . Cost effectiveness of a novel attempt to reduce readmission after Ileostomy Creation. JSLS 2017;21:e2016.00082 10.4293/JSLS.2016.00082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI, et al. . Acceptability, feasibility, and cost of telemedicine for nonacute headaches:a randomized study comparing video and Traditional consultations.. Journal of medical Internet research 2016;18:e140 10.2196/jmir.5221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dias AE, Limongi JCP, Hsing WT, et al. . Telerehabilitation in Parkinson's disease: Influence of cognitive status. Dement Neuropsychol 2016;10:327–32. 10.1590/s1980-5764-2016dn1004012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langabeer JR, Gonzalez M, Alqusairi D, et al. . Telehealth-Enabled Emergency Medical Services Program reduces Ambulance transport to Urban Emergency Departments. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:713–20. 10.5811/westjem.2016.8.30660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoaas H, Andreassen HK, Lien LA, et al. . Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:26 10.1186/s12911-016-0264-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacobs JJ, Ekkelboom R, Jacobs JP, et al. . Patient satisfaction with a teleradiology service in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:17:17 10.1186/s12875-016-0418-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bradbury A, Patrick-Miller L, Harris D, et al. . Utilizing remote Real-Time videoconferencing to expand access to Cancer genetic Services in Community Practices: a Multicenter Feasibility Study. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e23 10.2196/jmir.4564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. AlAzab R, Khader Y. Telenephrology application in rural and remote Areas of Jordan: benefits and impact on quality of life. Rural Remote Health 2016;16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fields BG, Behari PP, McCloskey S, et al. . Remote Ambulatory Management of Veterans with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep 2016;39:501–509. 10.5665/sleep.5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Georgsson M, Staggers N. Quantifying usability: an evaluation of a diabetes mHealth system on effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction metrics with associated user characteristics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:5–11. 10.1093/jamia/ocv099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, et al. . PatientsSatisfaction with and preference for Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:269–75. 10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy CE, Silverman E, Jia H, et al. . Effects of physical therapy delivery via home video telerehabilitation on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Rehabil Res Dev 2015;52:361–70. 10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holmes M, Clark S. Technology-enabled care services: novel method of managing liver disease. Gastrointestinal Nursing 2014;12:S22–S27. 10.12968/gasn.2014.12.Sup10.S22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levy N, Moynihan V, Nilo A, et al. . The Mobile insulin titration intervention (MITI) for insulin glargine titration in an Urban, Low-Income Population: randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. JMIR Res Protoc 2015;4:e31 10.2196/resprot.4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, et al. . Women veterans' experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e127 10.2196/jmir.4332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cottrell E, Cox T, O'Connell P, et al. . Patient and professional user experiences of simple telehealth for hypertension, medication reminders and smoking cessation: a service evaluation. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007270 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tabak M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, et al. . A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:935 10.2147/COPD.S60179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim H, Spaulding R, Werkowitch M, et al. . Costs of multidisciplinary parenteral nutrition care provided at a distance via mobile tablets. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:50S–7. 10.1177/0148607114550692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cancela J, Pastorino M, Tzallas AT, et al. . Wearability assessment of a wearable system for Parkinson's disease remote monitoring based on a body area network of sensors. Sensors 2014;14:17235–55. 10.3390/s140917235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Casey M, Hayes PS, Glynn F, et al. . Patients' experiences of using a smartphone application to increase physical activity: the SMART MOVE qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e500–e508. 10.3399/bjgp14X680989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsai CH, Kuo YM, Uei SL, et al. . Influences of satisfaction with telecare and family trust in older taiwanese people. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:1359–68. 10.3390/ijerph110201359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oliveira TC, Bayer S, Gonçalves L, et al. . Telemedicine in Alentejo. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:90–3. 10.1089/tmj.2012.0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minatodani DE, Chao PJ, Berman SJ, et al. . Home telehealth: facilitators, barriers, and impact of nurse support among high-risk dialysis patients. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:573–8. 10.1089/tmj.2012.0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akter S, D'Ambra J, Ray P, et al. . Modelling the impact of mHealth service quality on satisfaction, continuance and quality of life. Behav Inf Technol 2013;32:1225–41. 10.1080/0144929X.2012.745606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hung YC, Bauer J, Horsley P, et al. . Patient satisfaction with nutrition services amongst Cancer patients treated with autologous stem cell transplantation: a comparison of usual and extended care. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014;27 Suppl 2:333–8. 10.1111/jhn.12135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buis LR, Hirzel L, Turske SA, et al. . Use of a text message program to raise type 2 diabetes risk awareness and promote health behavior change (part I): assessment of participant reach and adoption. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e282 10.2196/jmir.2929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Houser SH, Ray MN, Maisiak R, et al. . Telephone follow-up in primary care: can interactive voice response calls work? Stud Health Technol Inform 2013;192:112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kairy D, Tousignant M, Leclerc N, et al. . The patient's perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:3998–4011. 10.3390/ijerph10093998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Mendelsohn JL, et al. . Electronic communication improves access, but barriers to its widespread adoption remain. Health Aff 2013;32:1361–7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Piette JD, Marinec N, Gallegos-Cabriales EC, et al. . Spanish-speaking patients' engagement in interactive voice response (IVR) support calls for chronic disease self-management: data from three countries. J Telemed Telecare 2013;19:89–94. 10.1177/1357633X13476234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gund A, Sjöqvist BA, Wigert H, et al. . A randomized controlled study about the use of eHealth in the home health care of premature infants. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:1 10.1186/1472-6947-13-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. ter Huurne ED, Postel MG, de Haan HA, et al. . Web-based treatment program using intensive therapeutic contact for patients with eating disorders: before-after study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e12 10.2196/jmir.2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chun YJ, Patterson PE. A usability gap between older adults and younger adults on interface design of an Internet-based telemedicine system. Work 2012;41 Suppl 1:349–52. 10.3233/WOR-2012-0180-349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee AC, Pulantara W, Barbara Sargent PT, et al. . The VISYTER telerehabilitation system for globalizing physical therapy consultation: issues and challenges for telehealth implementation. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 2012;26:90. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. . Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lua PL, Neni WS. Feasibility and acceptability of mobile epilepsy educational system (MEES) for people with epilepsy in Malaysia. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:777–84. 10.1089/tmj.2012.0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Finkelstein SM, MacMahon K, Lindgren BR, et al. . Development of a remote monitoring satisfaction survey and its use in a clinical trial with lung transplant recipients. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:42–6. 10.1258/jtt.2011.110413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gibson KL, Coulson H, Miles R, et al. . Conversations on telemental health: listening to remote and rural first nations communities. Rural Remote Health 2011;11:1656–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Doorenbos AZ, Eaton LH, Haozous E, et al. . Satisfaction with telehealth for Cancer support groups in rural american indian and Alaska native communities. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:765–70. 10.1188/10.CJON.765-770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Breen P, Murphy K, Browne G, et al. . Formative evaluation of a telemedicine model for delivering clinical neurophysiology services part I: utility, technical performance and service provider perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:1–8. 10.1186/1472-6947-10-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Everett J, Kerr D. Telehealth as adjunctive therapy in insulin pump treated patients: a pilot study. Practical Diabetes International 2010;27:9–10. 10.1002/pdi.1430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gardner-Bonneau D. Remote patient monitoring: a human factors Assessment. Biomed Instrum Technol 2010;44:71–7. 10.2345/0899-8205-44.s1.71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schein RM, Schmeler MR, Saptono A, et al. . Patient satisfaction with telerehabilitation assessments for wheeled mobility and seating. Assist Technol 2010;22:215–22. 10.1080/10400435.2010.518579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kruse CS, Kothman K, Anerobi K, et al. . Adoption factors of the Electronic Health Record: a Systematic Review. JMIR Med Inform 2016;4:e19 10.2196/medinform.5525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kruse CS, Mileski M, Alaytsev V, et al. . Adoption factors associated with electronic health record among long-term care facilities: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006615 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luna R, Rhine E, Myhra M, et al. . Cyber threats to health information systems: a systematic review. Technol Health Care 2016;24:1-9 10.3233/THC-151102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kruse CS, Mileski M, Moreno J, et al. . Mobile health solutions for the aging population:a systematic narrative analysis. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:1–13. 10.1177/1357633X16649790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. de Jong CC, Ros WJ, Schrijvers G, et al. . The effects on health behavior and health outcomes of Internet-based asynchronous communication between health providers and patients with a chronic condition: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e19 10.2196/jmir.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Young LB, Foster L, Silander A, et al. . Home telehealth: patient satisfaction, program functions, and challenges for the care coordinator. J Gerontol Nurs 2011;37:38–46. 10.3928/00989134-20110706-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCAHPS: patient's perspectives of care surve. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments.html (accessed 30 Apr 2017).

- 59. Cambridge Dictionary Effective. dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/English/effective (accessed 30 Apr 2017).

- 60. Dictionary.com Efficient. www.dictionary.com/browse/efficient (accessed 30 Apr2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016242supp001.pdf (8.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016242supp002.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)