Abstract

The mohalla or community clinics in Delhi, India aims to provide basic health services to underserved population in urban settings. This article reviews and analyzes the strengths & limitations of the concept and explores the role these clinics can play in (1) reforming urban health service delivery, (2) addressing health inequities, and (3) strengthening primary health care. These clinics provide basic healthcare services to people, in underserved areas, in a responsive manner, have brought health higher on the political agenda and the governments of a number of Indian states have shown interest in adoption (of a variant) of this concept. Strengths notwithstanding, the limitations of these clinics are: curative or personal health services focus and relatively less attention on public/population health services. It is proposed that while setting up these clinics, the government should built upon existing health system infrastructure such as dispensaries, addressing the existing challenges. The new initiative need not to be standalone infrastructure, rather should aimed at health system strengthening. These need to have a functional linkage with existing programs, such as Urban Primary Health Centres (U-PHCs) under national urban health mission (NUHM) and could be supplemented with overall efforts for innovations and other related reforms. The author proposes a checklist ‘Score-100’ or ‘S-100’, which can be used to assess the readiness and preparedness for such initiative, should other state governments and/or major city in India or other countries, plan to adopt and implement similar concept in their settings. In last 18 months, the key contribution of these clinics has been to bring health to public and political discourse. Author, following the experience in Delhi, envisions that these clinics have set the background to bring cleanliness-health-education-sanitation-social sectors (C-H-E-S-S or CHESS) as an alternative to Bijli-Sadak-Paani (B-S-P) as electoral agenda and political discourse in India. The article concludes that Mohalla Clinics, could prove an important trigger to initiate health reforms and to accelerate progress towards universal health coverage in India.

Keywords: Health equity, health systems strengthening, India, Mohalla Clinics, primary health care, universal health coverage

Introduction

The healthcare system in India has experienced a few successes in the last decade including elimination of poliomyelitis, yaws and maternal and neonatal tetanus.[1] Alongside, the traditional health challenges continue, i.e., low government expenditure on health, high prevalence of communicable diseases including tuberculosis, measles, emerging and re-emerging diseases; growing burden of non-communicable diseases including diabetes and hypertension; shortage of human resources for health and limited attention on primary healthcare (PHC) among other.[1] The reality of health services in India is the unpredictable availability of providers, lack of assured services, medicines, and diagnostics, and poorly functioning referral linkage. Not surprisingly, a large proportion of people, even for common illnesses such as fever, cough, and cold, seek care at secondary and tertiary level of government health facilities/institutions. This leads to overcrowding, long waiting hours, poor quality of service delivery, and people being unsatisfied with public health facilities. With this experience, – rather than spending on transport, visiting multiple times without service guarantee, waiting for hours to be seen by a doctor, and then spending money on medicines and diagnostics – people including poorest quintile of population find public health facilities too much of hassle, “vote with their feet” and attend either nonqualified providers or private providers, even at the cost of spending money from their pocket.[2,3]

Situation appears to have changed slightly in the last 10–15 years and yet there is much to be desired. On provision by the government, the National Health Mission of India has contributed to increased attention on health though not to the extent one would have liked to. Among state level health initiatives on service provision, the mohalla or community clinics of Delhi state, India, has received a lot of national and international attention and interest – mostly favorable – from media and health experts, alike.[3,4] A number of Indian states, all governed by a different political parties than the one in power in Delhi have shown interest in establishing similar clinics.[5,6]

This review has been written with objectives to document the concept, design, and evolution of mohalla clinics; to examine & analyze the strengths & limitations and suggest the way forward in a broader vision towards advancing universal health coverage (UHC) in India. It is expected that the learnings could guide the expansion in Delhi state and implementation and design of such facilities, for other settings.

Health Systems in Delhi, India

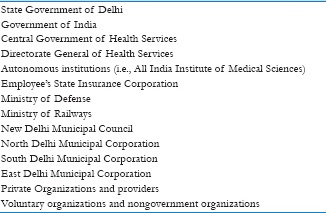

Delhi is a city-state in India, with a population of 1.68 crore (or 16.8 million) in 2011 with 97.5% of population living in urban area, 1483 km2 geographical area, and population density of 11,297 (range 3800–37,346/km2). It has nearly 18 lakh (1.8 million) or 11% population living in slums[7] and a large proportion of this population is migrants from various parts of country. Delhi is the most populous urban agglomeration in India and the 3rd largest urban area in the world. The health services in Delhi are provided by 12 different agencies (if three municipal corporations are counted separately then the number would be 14) [Box 1]. The number of health facilities available in Delhi varies depending on sources. As on March 31, 2014, there were 95 hospitals, 1389 dispensaries, 267 maternity homes and subcenters, 19 polyclinics, 973 nursing homes, and 27 special clinics in Delhi.[8] In addition,15 government-run medical colleges in allopathic system of medicine.

Box 1.

Agencies providing health services in Delhi, India

The Government of Delhi owns nearly one-fourth to one-fifth of all health facilities with nearly 10,000 hospital beds, over 200 dispensaries and polyclinics, among many other. The health facilities run by the Government of Delhi examine around 3.35 crore (33.5 million) outpatients and treat nearly 6 lac (600,000) hospitalized patients, every year. There is high density of private providers and large private hospitals and small clinics in the city-state. Per capita government health expenditure in Delhi state was INR 1,420 in 2012–13 while the average for the major states India in that year was INR 737 per capita. Much of the remaining health expenditure is out of the pockets of the people.[9] Nearly 55% of hospital care in urban areas (national average: 68%) is from private sector. In addition, 87% of males and 71% of females in Delhi attended private providers for their outpatient (national average 76% and 73%, respectively).[10]

Mohalla Clinics: The Concept and Design

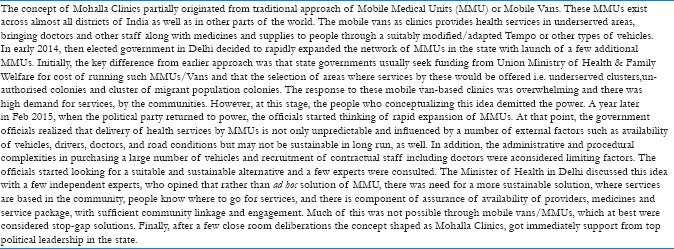

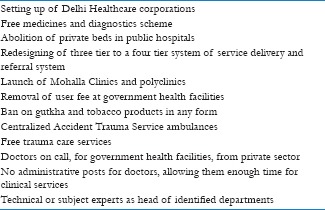

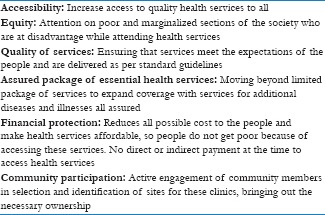

The mohalla or community clinics initiative was launched by the government of Delhi in July 2015, with one clinic in a slum locality.[2,11,12] The idea had origin in the success of mobile vans or mobile medical units (MMU). It was then supplemented by desire of the top political leadership to fulfill electoral promise and commitment to strengthen health systems rather than providing ad hoc solutions [Box 2]. The key design aspects of these clinics are summarized in Box 3.

Box 2.

Mohalla Clinics: Origin of idea

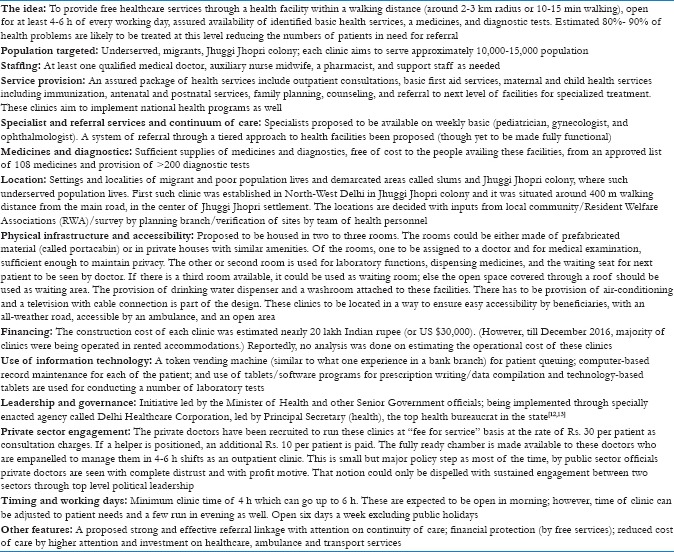

Box 3.

Mohalla Clinics of Delhi, Key concepts

Evolution of Mohalla Clinics (July 2015–December 2016)

The first mohalla clinic of Delhi was inaugurated on 19 July 2015 at Peeragarhi area of West Delhi. It took another 9 months to set up additional 100 clinics. By December 2016, a total of 106 clinics were established across all 11 districts and in 55 of total 70 assembly constituencies of the state.[11] The Government of Delhi had planned to launch 1000 such clinics However, in spite of high political ownership and huge demand from the community, nearly 10% of the target numbers of these clinics could be established by the target timeline of December 2016.[14,15] The delay in setting up of planned numbers of clinics has been attributed to factors, including insufficient advance planning (there was no operational plan developed till 1 year in the implementation), difficulty in selection of the sites (the land is not controlled by the state government), delay in approvals of proposals at various levels, and frequent change in technical leadership in health department among other.

The first clinic was set up in Portacabin structure at government land, however, the plan to acquire land met hurdles and most of the subsequent clinics, nearly 100, were opened in private houses (rented and rent free, both). Another attempt to expedite the process by opening these clinics in government schools met administrative hurdle and could not materialize till 31 Dec 2016, pending approvals from authorities.[16]

Majority of the clinics had been started in the early 2016 and became popular among the community, soon thereafter. An official release from the Government of Delhi reported that by July 2016, nearly 800,000 people had availed health services & 43,000 pathological tests were conducted in 5 months.[17] Every clinic on average was catering to 70–100 patients per working day. In September–October 2016, when Delhi witnessed an outbreak of dengue and Chikungunya diseases and the health facilities were flooded with the patient, the mohalla clinics became a key entry point for patients to get examined and laboratory test for dengue done. This was considered a major relief for large health facilities and allayed the crisis in the city.[18] By the end of the year 2016, around 1.5 million patients were examined at these facilities, most of which were functioning for less than a year till then.[19]

These facilities became an area of interest for many external experts, opposition parties, and journalists, who visited the clinics, scrutinized the functioning and interacted with beneficiaries. Most of such visitors reported the high demand for services at these clinics and applauded the concept. Leading medical journal, The Lancet in editorial in December 2016 made observation that “a network of local mohalla clinics that are successfully serving populations otherwise deprived of health services.”[20] Many international and Indian newspapers hailed the concept and suggested that these clinics meet core concepts of universal health coverage and increase access to quality healthcare services by poorest of the people and reduce financial burden associated with access to health services.[2,21] The unpublished data from the government of Delhi highlighted that 40-50% of all patients who attended these clinics had come to a government health facility for the first time. Many unqualified providers, who has clinics in the settings where Mohalla Clinics have been set up, acknowledge the reduced patient load.

There is widespread acknowledgment that these clinics have improved access to health services by qualified providers, to the poorest of the poor, though this needs to be studied and documented in more systematic manner.

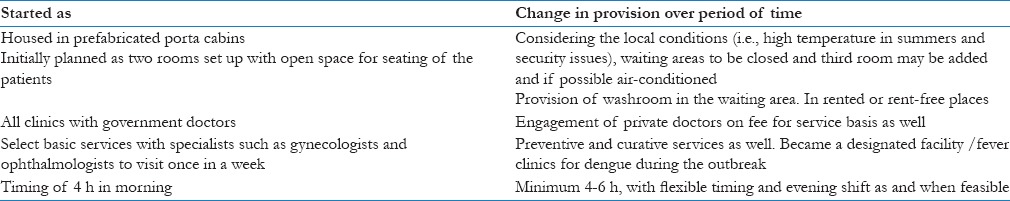

There has been a number of revisions/improvements/mid-course corrections in the design, all aiming to make these clinics people friendly [Table 1]. The government, alongside the mohalla clinics, made a series of policy interventions during this period to reform healthcare service delivery, which received less attention than the clinics [Box 4]. Some of these decisions, i.e., engagement of private sector, restructuring health service delivery in three to four tiers and abolition of any type of user fee at government facilities, were very much linked to effective utilization and increasing access to health services, making the services affordable and reducing out of pocket expenditure by people.

Table 1.

Evolution of Mohalla Clinics: (July 2015 to Dec 2016)

Box 4.

Key policy interventions in health sector, Delhi, India (2015-16)

Analysis and Discussion

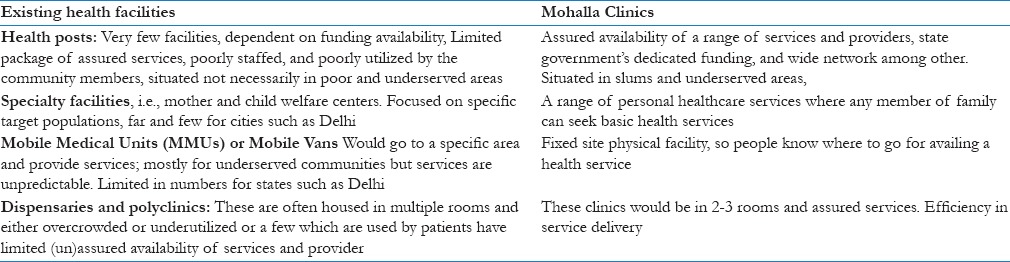

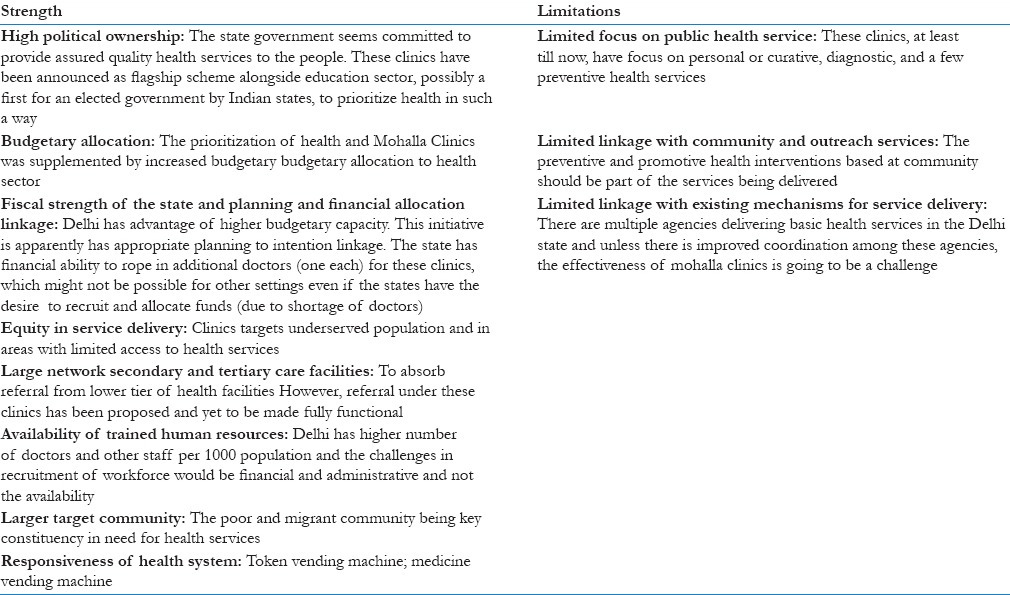

The concept has a number of widely acknowledged strength to become successful health intervention and a few limitations as well [Table 2]. Therefore, it is not a surprise that a number of Indian states, i.e., Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and a few municipal corporations (i.e., Pune) have shown interest to start a variant of these clinics.[5,6,22,23,24] There are at least two “proofs of concept” of success of these clinics. On demand side: people have “voted by their feet” and there is high demand for services at these clinics. Second proof is political interest, (which is very important from political economy perspective) and inclination of a number of Indian states to start health facilities on similar design. The politicians and political leaders have a knack to feel pulse of people and this is one such initiative which is widely popular amongst masses. These clinics, analyzed from health systems perspective, performs well on accessibility, equity, quality, responsiveness, and financial protection, among other [Box 5].

Table 2.

Comparison of mohalla clinics with existing health facilities

Box 5.

Mohalla clinics: key principle

On budgetary allocation, these clinics had been allocated INR 200 crore (approximately US$ 30 million) for settings up 1000 such clinics (at INR 20 lakh [or US$ 30,000] per clinic). which was approx 4% of total health budget of the Government of Delhi (Total health budget INR 5,259 crores (or US$ 784 million) in the year 2016–17.[25] However, there is need for detailed estimates on both capital and recurrent cost for making these clinics functional and get resources approved to ensure financial sustainability. While capital cost has been estimated, the recurrent cost of human resources, cost of diagnostics and medicines, and operational costs are not being discussed, which would be additional outlay of nearly 300 crore or US$ 45 million per annum (author's estimate).

For efficient functioning and success of initiative, it is important that user experience is good, across the continuum of care. One of the promised reforms in Delhi has been developing a four tier healthcare system (first mohalla clinics; second polyclinics; third multispecialty hospital; fourth super specialty hospitals and medical colleges.) with referral linkages, which is respected at every level. Alongside the mohalla clinics, the next level is polyclinics (150 of such clinics had been proposed by December 2016 and 23 have already been established). Hence, a well respected (at all levels) and functioning referral linkage should be given equal if not more attention. Bringing people to public health facilities is important but not enough, and providing them quality and assured care through the “continuum of care” is a must to retain them.

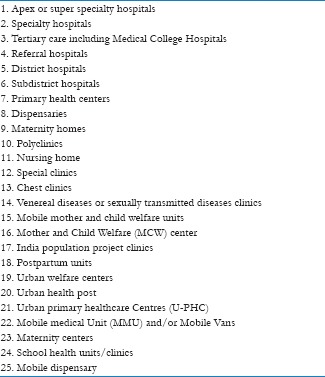

The health services in Delhi state are provided through nearly 25 different types of health facilities [Box 6]. At times, it is difficult to differentiate one from other, even program managers lack clarity on provision of services and many of these facilities which are more or less similar.[26] In this background, as an outsider with limited information, some people may think mohalla clinics just another such health facility. However, well thought through design aspects makes mohalla clinics standing out, while compared with existing health facilities [Table 3]. Nonetheless, considering that the multiple health facilities make access to health services complicated, tedious, and difficult for common people, the harmonization/integration of function and the convergence/coordination of multiple types of health facilities run by different agencies is an area to be addressed, proactively. The focus of majority of the existing health facilities is curative or clinical or largely personal health services with limited attention and capacity to deliver public or population health services.

Box 6.

Types of health facilities functioning in Delhi

Table 3.

Mohalla clinics: Strengths and limitations of the concept and design

From other perspective, Mohalla clinics are often referred as a synonym for delivery of primary health care (PHC), which is not fully true, at least in the current design form. PHC is a comprehensive concept which offers a balanced mix of preventive-promotive-curative- diagnostic-rehabilitative or in other words – clinical and public health services. To make the point further, the public health works before the occurrence of diseases while clinical services aim to treat patients once they have acquired an illness. The public health needs vary with geography and a few areas need better sanitation, while other needs greater awareness about nutrition, or information on healthy lifestyle. The key issue is that in the current design of Mohalla Clinics, is limited attention on population or public health services at these facilities. These clinics do not sufficiently cover the services such as sanitation, drinking water, importance of hygiene, and awareness about nutrition. In short, Mohalla Clinics, at least in current form, focuses on clinical/curative services and can not be considered to deliver comprehensive PHC.

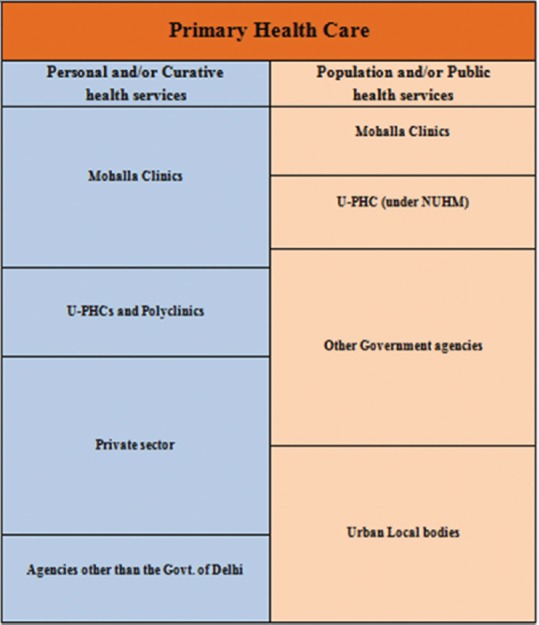

In this context, the urban PHCs (U-PHCs) under National Urban Health Mission (NUHM)[27] could be complementary to these clinics, where mohalla clinics may focus on clinical/curative and diagnostic services while U-PHC in addition to curative services deliver public health services with clearly established referral linkage. The convergence between U-PHC and Polyclinics should also be considered. The U-PHCs and/or polyclinics along with three- four lower levels of facilities including mohalla clinics could be an effective hub to deliver comprehensive PHC to approximately 50,000–70,000 population. In any case, country such as India, where health is state subject and union government only guide the policy process, a sustainable solution for healthcare is “convergence” by design between state-owned initiatives and union MoHFW programs. One schematic of how mohalla clinics and U-PHCs and/or polyclinics converge to strengthen PHC systems is given in Figure 1. A related aspect of this convergence could be community participation. Mohalla clinics have higher community acceptance for the reason of being in community settings and offer clinical services, a preferred and felt need of community members. Similar response to public health services may not be given by the community members and that is where the proposed Mahila Aarogya Samiti (MAS) under NUHM can add value.[27]

Figure 1.

A conceptual model for coordinated delivery of primary health care services in urban areas

The health sector similar to other social sectors is considered inefficient and a well-functioning PHC system is expected to bring efficiency in service delivery by reducing the cost of care. Through PHC, 80–90% of illnesses can be treated and saving scarce specialist services available at higher level of government health facilities (i.e. District hospitals) for patients in need. Bringing efficiency in health sector requires coordinated actions at clinical and public health services.

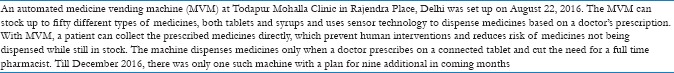

In Delhi, there has been a number of innovations to improve health service delivery, i.e., doctors on contract for “fee for service” basis, rented premises for Mohalla Clinics, and flexible and variable timing of clinics, among other. Besides, a number of other initiatives are in pipeline, i.e., optimal use of interns and postgraduate students from medical colleges for staffing of select facilities. There is need for optimally exploring the use of information technology in these clinics and other health services and a linked innovation is medicine vending machines [Box 7].[28,29]

Box 7.

Medicine vending machine (MVM): Use of technology to facilitate access

There are design elements in these clinics which are desired in any health system, i.e., potential to eliminate unqualified providers; decongestion of higher level health facilities, making specialists available for those who need them, and thus bringing efficiency in health service delivery. These are challenge for health systems in most of Indian states, so the concept is applicable across the spectrum and not to state of Delhi only. These clinics are fixed site facilities which patients visit to seek healthcare. However, in months ahead, the provision/mechanisms have to be established, to offer preventive and promotive health services to community members for emerging non communicable diseases and associated risk factors (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, various types of cancers and ophthalmic issues to start with), counsel them, and bringing to health facility for medical attention. An unsuccessful attempt to set up clinics in schools should not be a deterrent and government should continue to explore the way through these clinics to strengthen school health services. With nearly 40 lakh students[26] in schools across Delhi an effective linkage of mohalla clinics with schools could become a game changer for better health of younger generation.

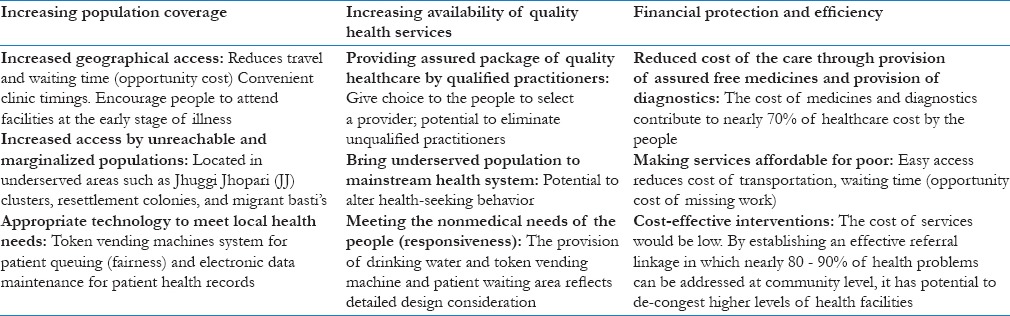

The global experience shows that standalone reforms are not enough and it is always better to have a series of linked reforms. The policy decisions and proposed reforms initiated by the government [Box 4] need to be accelerated to get a holistic advancement in healthcare. Mohalla clinics could prove an important tool to advance universal health coverage (UHC) & health systems strengthening in India [Table 4].

Table 4.

Mohalla Clinics: Analyzing from perspective of universal health coverage and health systems approach

These clinics have placed healthcare higher in political discourse, which is already a partial success; however, this is still far from what was the case with Bijli-Sadak-Pani (BSP) (or electricity-road-water) nearly 15 years ago. It is possible that with more of similar initiatives on health (and education) by increasing number of states in India, Swachchata-Swashthya-Shiksha– Safaai-Saamaajic kshetra (cleanliness-health-education-sanitation-social sector or CHESS, in short) becomes the next electoral agenda, replacing B-S-P. This could be the CHESS, Indian people would not mind if politicians start to play more frequently.

How Mohalla Clinics could be Strengthened?

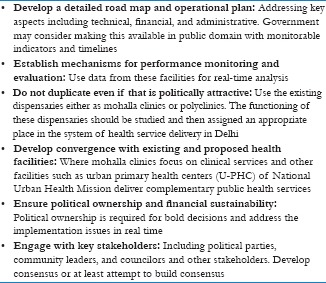

The clinics delivering assured health services to 70 odd patients per facility every day, six days a week, free for beneficiaries and at nominal cost to government requires limited additional proof of success. However, the real success of these clinics would be in delivering health outcomes with long-term sustainability. To further strengthen the implementation and ensure that these clinics remain on agenda, adopted by additional states and sustained in Delhi even when the government change, and meet the needs of people, a few points could be considered by top policy makers [Box 8].

Box 8.

Suggestions to strengthen mohalla clinics and primary health care in Delhi, India

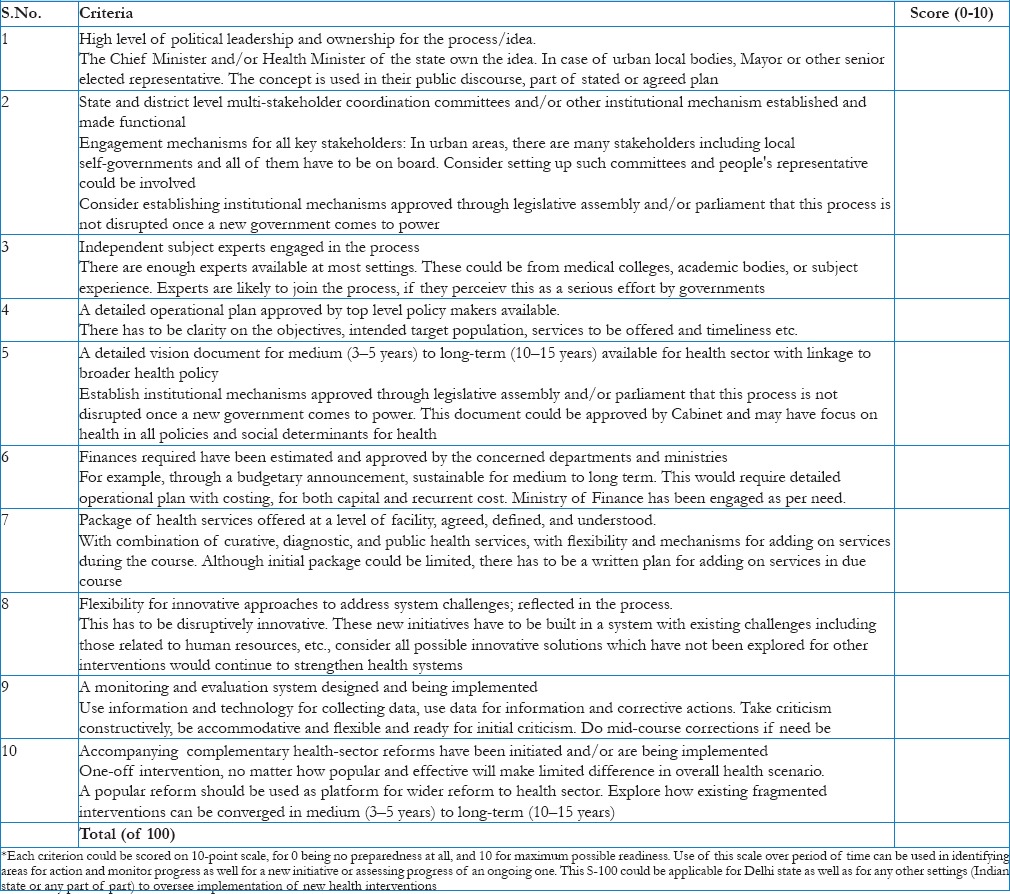

The roll-out of such initiatives is a process, which needs to be guided, monitored with on course corrections. This is possible when the policy makers and program managers have a comprehensive approach to implement and monitor such initiatives. To facilitate this, the author proposes a checklist “Score100” or ‘S-100’, which can be used by policy makers and program managers to assess the readiness and preparedness and then monitor the progress for effective implementation [Table 5]. The checklist could be used at multiple levels of planning (ward/block, district and state).

Table 5.

Score-100 or S-100 checklist to assess preparedness and readiness for introducing or scaling up an intervention (i.e., the concept similar to mohalla clinics)*

Finally, most of the evidence from these clinics are unsystematic and experiential. For one, experience and learnings from these clinics needs to be documented in detail, supported by data collected through mechanisms part of these clinics. Second, once there is sufficient expansion of these clinics and enough time given for system to establish, it would be useful to conduct detailed, rigorous and independent evaluation of these clinics and other reforms, to derive lessons and to take corrective actions.

Conclusion

The mohalla clinics have brought health higher on the political discourse and agenda in Delhi states and there is high level of interest by Indian states. These clinics are delivering personal (curative and diagnostic) health services; however, strengthening of PHC would require a holistic approach and more attention on population and/or public health services through targeted initiatives. While some people would like to consider the mohalla clinics as another type of health facility, the concept has potential to initiate reform in health sector in India. It is proposed that in addition to establishing new facilities, a lot can be built upon existing health system infrastructure such as dispensaries, and convergence of functioning of these clinics with other existing/planned mechanisms such as U-PHC under NUHM. In addition, such initiative has to be supplemented with health system innovations and reforms. The Mohalla Clinics are a good start; however, the bigger success of this concept would be when it (1) brings attention on need for stronger primary health care across the country (2) health services acquire the ability to influence electoral outcomes and (3) catalyze efforts to strengthen health systems, amongst other. These steps would be essential as India aims to advance towards universal health coverage. Mohalla Clinics may prove one such small but important trigger in this remarkable journey.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are solely of the author and should not be attributed to any institution/organization, he has been affiliated in the past or at present.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The author has advised the Government of Delhi, on various healthcare reforms including conceptualization, designing and implementation of the mohalla clinics.

References

- 1.Government of India. Draft National Health Policy of India. Nirrman Bhawan, New Delhi: MoHFW, Govt. of India; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahariya C. Delhi's mohalla clinics: Maximizing potential. Econ Polit Wkly. 2016;51:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Press Trust of India. Delhi Gets First ‘Aam Aadmi Clinic’, CM Kejriwal Says 1000 More in Line. Indian Express. Delhi: 2015. Jul 20, [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/delhi-gets- first-aam- aadmi-clinic-cm-kejriwal-says-1000-more-in-line/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centre for Civil Society. Delhi Citizens Handbook 2016. New Delhi: Perspective on Local Governance in Delhi; 2016. pp. 130–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakashi R. Karnataka to Replicate Delhi's ‘Mohalla Clinics’. Times of India, Bengaluru. 2016. Oct 27, [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/Karnataka-to-replicate-Delhis-Mohalla-clinics/articleshow/55095782.cms .

- 6.Sharma R. Eye on Polls, Gujarat Govt. to Set Up ‘Mohalla Clinics’ in 4 cities. Indian Express, Ahmedabad. 2016. Oct 07, [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.indianexpress.com/article/cities/ahmedabad/eye-on-polls-gujarat-govt-to-set-up-mohalla-clinics-in-4-cities-3069359/

- 7.Government of Delhi. Delhi Population: Statistical Abstract of Delhi; 2014. Delhi: Department of Statistics and Economics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of Delhi. Economic survey 2016-17 Department of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of Delhi. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of India. National Health Profile 2015; Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi: MoHFW, Govt. of India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Sample Survey Organization. Key Indicators of Social Consumption in India: Health. 71st Round: January – June 2014. Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. New Delhi. 2014:1–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government of Delhi. Mohalla Clinics. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.dshm.delhi.gov.in/pdf/AamAadmiMohallaClinics.pdf .

- 12.Rao M. The Clinic at Your Doorstep: How the Delhi Government is Rethinking Primary Healthcare; 25 May. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.scroll.in/pulse/807886/the-clinic-

- 13.Government of Delhi. Delhi Healthcare Corporation. Dept. of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of Delhi. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perappadan BS. Cabinet Approves Delhi Healthcare Corporation. The Hindu, Delhi; 01 October. 2015. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/cabinet-approves-delhi-healthcare-corporation/article7709317.ece .

- 15.IANS. AAP-Centre Tussle Ruled in 2016, Ball in SC's Court in 2017. The New Indian Express. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/delhi/2016/dec/19/aap-centre-tussle-ruled-in-2016-ball-in-scs-court-in- 2017-1550808-1.html .

- 16.No Source. Parents Object to Mohalla Clinics in Govt. Schools. The Tribune; 01 August. 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/delhi/parents-object-to-mohalla-clinics-in-govt-schools/274276.html .

- 17.Hindustan Times. Eight Lakh Treated in Five Months at Delhi Mohalla Clinics. New Delhi; 10 August. 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/eight-lakh-treated-in-five-months-at-delhi-mohalla-clinics/story-KQl2baCrJ5lz8TS3ZmuziN.html .

- 18.Indian Express. Delhi: Dengue Testing Facility at Mohalla Clinics from Next Month. New Delhi: Indian Express; 2016. Aug 10, [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/delhi-dengue-testing-facility-at-mohalla-clinics-from-next-month-2966750/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma DC. Delhi looks to expand community clinic initiative. Lancet. 2016;388:2855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Lancet. Universal health coverage-looking to the future. Lancet. 2016;388:2837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadhwa V. What New Delhi's Free Clinics Can Teach America about Fixing its Broken Health Care System? Washington Post; 11 March. 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2016/03/11/what-new-delhis-free-clinics-can-teach-america-about-fixing-its-broken-health-care-system/?utm_term=0.3bb5b0a51745 .

- 22.Daily News and Analysis. AAP to Inaugurate its First Mohalla Clinic in City. Mumbai; 21 August. 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-aap-to-inaugurate-its-first-mohalla-clinic-in-city-2247324 .

- 23.Lahariya C. Abolishing userfee and private wards in public hospitals. Econ Polit Wkly. 2016;51:30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadkari S. Towing on AAP Line, PMC Mulls Mohalla Clinics. Pune Mirror; 12 August. 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.punemirror.indiatimes.com/pune/civic/Towing-AAP-line-PMC-mulls-Mohalla-Clinics/articleshow/53657966.cms .

- 25.Govt. of NCT of Delhi. Budget Speech 2016-17. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.delhi.gov.in/wps/wcm/connect/84861b0044d0f23e9990db82911e8eeb/Budget+Speech+2016-17+English.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&lmod=-359219120 .

- 26.Directorate of Economics and Statistics. Delhi Statistical Handbook 2015. New Delhi: Govt. of NCT of Delhi; 2015. pp. 223–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Government of India. Framework for Implementation for National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi: MoHFW, Govt. of India; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutt A. Hindustan Times. Delhi; 23 August. Delhi: Mohalla Clinic Gets a Medicine Dispensing Machine; 2016. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/delhi-mohalla-clinic-gets-a-medicine-dispensing-machine/story-Hui5HPRP4cKI0rehE4oujM.html . [Google Scholar]

- 29.USAID. First of its Kind Medicine Vending Machine Inaugurated. [Last accessed on 27 Sep 2016]. Available from: https://www.usaid.gov/india/press-releases/aug-23-2016-first-its-kind-medicine-vending-machine-inaugurated-aam-aadmi .