Abstract

Background/aims

To determine the incidence of any diabetic retinopathy (any-DR), sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (STDR) and diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and their risk factors in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) over a screening programme.

Methods

Nine-year follow-up, prospective population-based study of 366 patients with T1DM and 15 030 with T2DM. Epidemiological risk factors were as follows: current age, age at DM diagnosis, sex, type of DM, duration of DM, arterial hypertension, levels of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), triglycerides, cholesterol fractions, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR).

Results

Sum incidence of any-DR was 47.26% with annual incidence 15.16±2.19% in T1DM, and 26.49% with annual incidence 8.13% in T2DM. Sum incidence of STDR was 18.03% with annual incidence 5.77±1.21% in T1DM, and 7.59% with annual incidence 2.64±0.15% in T2DM. Sum incidence of DMO was 8.46% with annual incidence 2.68±038% in patients with T1DM and 6.36% with annual incidence 2.19±0.18% in T2DM. Cox's survival analysis showed that current age and age at diagnosis were risk factors at p<0.001, as high HbA1c levels at p<0.001, LDL cholesterol was significant at p<0.001, eGFR was significant at p<0.001 and UACR at p=0.017.

Conclusions

The incidence of any-DR and STDR was higher in patients with T1DM than those with T2DM. Also, the 47.26% sum incidence of any-DR in patients with T1DM was higher than in a previous study (35.9%), which can be linked to poor metabolic control of DM. Our results suggest that physicians should be encouraged to pay greater attention to treatment protocols for T1DM in patients.

Keywords: Retina, Telemedicine, Epidemiology

Introduction

It is estimated that more than 200 million people worldwide currently have diabetes and that number is predicted to rise by over 120% by 2025.1 It has become a chronic disease with several complications. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is classified as type 1 diabetes (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes (T2DM), gestational diabetes, monogenic diabetes and secondary diabetes.2 There is a current trend towards more children developing T1DM and more than half a million children are estimated to be living with the disease.

The most important ocular complication is diabetic retinopathy (DR), a common cause of blindness in Europe.3 Development of DR is similar in both DM types. DR screening uses a non-mydriatic fundus camera, a cost-effective way of screening DM populations.4 Screening frequency varies according to DM type.5 Our group rolled out a screening programme in 2000 that included general practitioners and endocrinologists,6 and we reported an increase in the incidence of DR in a previously published study.7

In this study, we determine the incidence of any-DR, sight-threatening retinopathy (STDR) and diabetic macular oedema (DMO) in patients with T1DM and its differences in patients with T2DM.

Materials and methods

Setting: The reference population in our area is 247 174. The total number of patients with DM registered with our healthcare area is 17 792 (7.1%).

Design: A prospective, population-based study, conducted from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2015. A total of 366 patients with T1DM and 15 030 with T2DM were screened.

Power of the study: Our epidemiologist estimates the detection of a ±3% increase in risk and 95% accuracy.

Method: Screening for DR was carried out with one 45° field retinography, centred on the fovea. If DR was suspected, a total of nine retinographies of 45° were taken and a complete screening is described elsewhere.8 Due to the difficulty in obtaining images from patients with T1DM under 12 years old, only those aged >12 years were included.

In this study, DR is classified into (i) no-DR, (ii) any-DR—level 20–35 of the ETDRS, (iii) STDR—defined as level 43 or worse by the ETDRS. The term ‘DMO’ includes ‘extrafoveal’ and/or ‘clinically significant macular oedema (CSMO)’ according to the ETDRS classification.9

Measures of kidney diabetic disease were determined by (i) serum creatinine; (ii) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), measured by the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation (CKD-EPI); (iii) urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR), classified in normoalbuminuria defined as UACR <30 mg/g, microalbuminuria as UACR 30–299 mg/g and macroalbuminuria as UACR ≥300 mg/g.

At the end of the study, all patients with T1DM were visited, and a fundus nine-field retinographies was carried out by an ophthalmologist to confirm the number of patients with DR and if any new patients with DR are previously not diagnosed.

Inclusion criteria: Patients with T1DM >12 years old, and all patients with T2DM.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with other specific types of diabetes, and patients with gestational DM.

Ethical adherence: The study was carried with the approval of the local ethics committee (approval no. 13-01-31/proj6) and in accordance with revised guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical methods

Data evaluation and analysis was carried out using SPSS V.22.0 statistical software package and p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Descriptive statistical analysis of quantitative data was made by the determination of mean, SD, minimum and maximum values, and the 95% CI. For qualitative data, we used the analysis of frequency and percentage in each category. Differences were examined using the two-tailed Student's t-test to compare two variables or using one-way analysis of variance if we were comparing more than two variables. Inferential analysis for qualitative data was made by the χ2 table and the determination of the Fisher test for quantitative data. Multivariate analysis was carried out using Cox survival regression analysis.

Results

Demographic variables of sample size

In the 9-year follow-up (1 January 2007 to 31 December 2015), a total of 366 patients with T1DM and 15030 with T2DM were screened (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive values of the sample

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with T1DM | 117 | 116 | 121 | 124 | 121 | 144 | 129 | 142 | 127 |

| Number of patients with T2DM | 4910 | 4873 | 5191 | 5243 | 5264 | 6193 | 5494 | 5983 | 5026 |

| T1DM men | 75 64.1% |

76 65.5% |

79 65.29 |

81 65.32% |

78 64.46% |

93 64.58% |

84 65.11% |

93 65.49% |

83 65.35% |

| T2DM men | 2881 57.31% |

2802 56.16% |

2890 54.41% |

3007 56.03% |

2933 55.60% |

3594 56.72% |

3131 55.69% |

3511 57.33% |

2817 56.05% |

| T1DM mean age | 33.08±10.1 | 33.11±10.01 | 33.1±10.1 | 34.17±10.08 | 34.64±10.05 | 34.86±10.02 | 35.22±10.11 | 35.19±10.03 | 35.58±10.14 |

| T2DM mean age | 64.62±12.23 | 66.27±12.32 | 65.39±12.41 | 65.69±11.7 | 65.22±12.12 | 65.33±12.08 | 65.87±12.07 | 65.88±11.94 | 65.84±12.39 |

| T1DM duration | 12.74±8.69 | 12.72±8.71 | 12.69±8.74 | 12.77±8.77 | 12.79±8.67 | 12.81±8.58 | 12.78±8.71 | 12.86±8.78 | 12.81±8.77 |

| T2DM duration | 8.37±6.92 | 8.66±6.78 | 8.57±6.12 | 8.23±6.81 | 8.29±6.56 | 8.23±6.82 | 8.28±6.11 | 8.34±6.83 | 8.35±6.77 |

| T1DM mean HbA1c | 8.28±1.51 4.9–14.2 |

8.31±1.49 5–15.1 |

8.29±1.44 5–14.9 |

8.33±1.47 4.9–15 |

8.25±1.5 4.71–15 |

8.40±1.4 5.3–15.2 |

8.32±1.22 5.1–14.32 |

8.59±1.3 5–14.7 |

8.77±1.14 5.5–15.1 |

| T2DM mean HbA1c | 7.37±1.48 3.9–14 |

6.82±1.24 4.37–12 |

7.02±1.7 3.8–15 |

7.47±1.5 4.5–14.5 |

7.3±1.5 4–15.5 |

7.63±1.4 4.3–15.8 |

7.62±1.41 4.3–15.8 |

7.64±1.4 4–15.6 |

7.61±1.5 4.2–15 |

| Incidence of DR and its severity. | |||||||||

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| T1DM Any-DR |

16 13.67% |

18 15.51% |

17 14.04% |

18 14.51% |

19 15.7% |

23 15.97% |

20 15.5% |

22 15.49% |

20 15.74% |

| T2DM Any-DR |

390 7.94% |

384 7.88% |

411 7.06% |

424 8.05% |

407 7.73% |

533 8.6% |

489 8.9% |

529 8.84% |

415 8.25% |

| T1DM STDR | 6 5.13% |

7 6.03% |

7 5.78% |

8 6.45% |

7 5.78% |

9 6.25% |

7 5.42% |

8 5.63% |

7 5.51% |

| T2DM STDR | 131 2.6% |

125 2.5% |

132 2.48% |

134 2.49% |

141 2.67% |

170 2.68% |

162 2.88% |

174 2.84% |

139 2.76% |

| T1DM DMO | 2 1.71% |

3 2.58% |

3 2.47% |

4 3.22% |

3 2.47% |

5 3.47% |

3 2.32% |

4 2.81% |

4 3.15% |

| T2DM DMO | 104 2.00% |

101 2.02% |

112 2.11% |

114 2.12% |

110 2.08% |

150 2.36% |

135 2.40% |

153 2.49% |

122 2.42% |

Values are presented as number or mean±SD and range; also, we describe the incidence of DR and its different types.

DMO, diabetic macular oedema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; STDR, sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Each patient with T1DM was screened 4.11±0.77 times over the 9 years compared with 3.19±1.12 for each patient with T2DM.

Sample characteristics of patients with T1DM at the end of study were as follows: current age 35.19±10.03 years, age at diagnosis 22.04±9.11 years and DM duration 13.63±8.42 years. By current age, DR did not appear in patients aged <20 years but was present in 27 (39.70%) patients aged 20–30 years, in 74 (47.74%) patients aged 30–40 years and in 66 (61.11%) patients aged >40 years.

Mean HbA1c values were 8.38±1.16% in patients with T1DM and 7.38±1.29% in patients with T2DM. Table 2 shows the HbA1c percentages according to DM duration. It is interesting to observe that 14.7% of patients with DM duration <5 years present DR and HbA1c percentages decrease and in patients with any-DR with an increase in DM duration, which might explain why patients with >20 years DM duration have only 81.08% of DR incidence.

Table 2.

Values of HbA1c and incidence of diabetic retinopathy (DR), according to duration of diabetes mellitus (DM)

| DM duration (years) |

DR incidence patients (%) | HbA1c |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | 15 (14.70) | No DR | 7.74±1.19% |

| Any-DR | 10.45±1.61% | ||

| Mean | 8.01±1.47% | ||

| 5–10 | 36 (41.86) | No DR | 7.85±1.78% |

| Any-DR | 8.93±1.78% | ||

| Mean | 8.03±1.82% | ||

| 10–15 | 32 (54.37) | No DR | 8.11±2.56% |

| Any-DR | 9.57±1.47% | ||

| Mean | 8.48±2.41% | ||

| 15–20 | 30 (66.66) | No DR | 7.39±0.51% |

| Any-DR | 8.93±1.47% | ||

| Mean | 7.91±1.68% | ||

| >20 | 60 (81.08) | No DR | 7.54±0.82% |

| Any-DR | 8.57±1.41% | ||

| Mean | 7.94±1.19% | ||

Study of differences between patients with T1DM and T2DM

Table 1 shows differences between both DM types. Excluding differences in age, men are more frequent in both DM types but less in T1DM, being significant at p<0.001. Also, the statistical analysis of mean differences between T1DM and T2DM, using the two-tailed Student t-test, was significant for diabetes duration (p<0.001) and HbA1c levels (p<0.001).

Study of incidence of DR

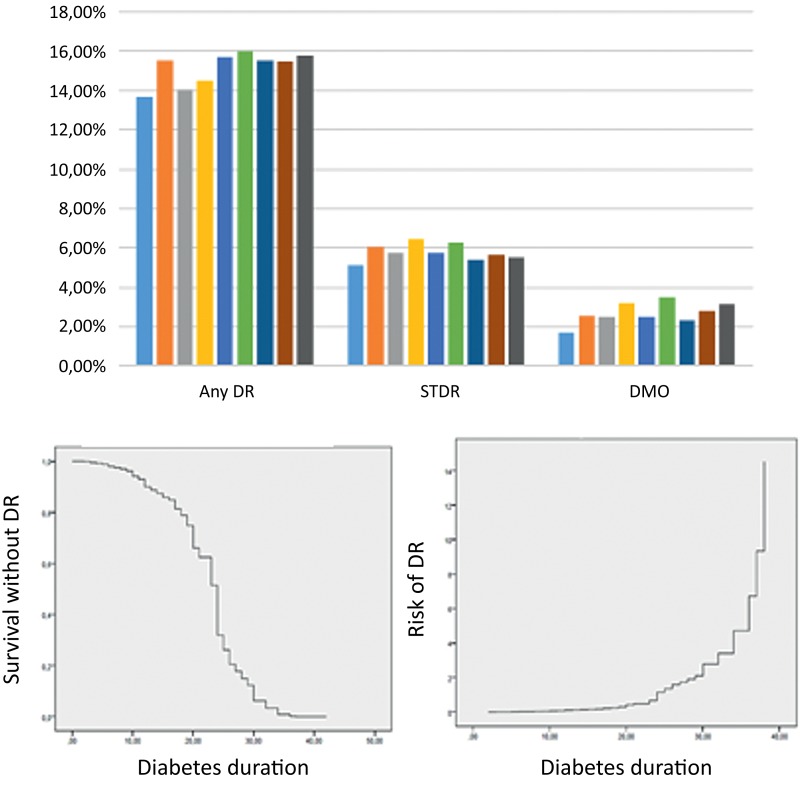

A total of 173 patients with T1DM (47.26%) developed any-DR at 9 years with mean annual incidence of 15.16±2.19% (13.67%–15.97%), 3982 patients with T2DM developed any-DR (26.49%) with a mean annual incidence of 8.13% (7.06%–8.9%) (figure 1A and table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Incidence of diabetic retinopathy (DR) and its severity. (B) Survival analysis graphs.

Sum incidence of STDR in patients with T1DM was 18.03% with an annual incidence of 5.77±1.21% (5.13%–6.45%) and sum incidence in patients with T2DM was 7.59% with an annual incidence of 2.64±0.15% (2.48%–2.88%).

Sum incidence of DMO in patients with T1DM was 8.46% with an annual incidence of 2.68±038% (1.71%–3.22%) and sum incidence in T2DM was 6.36% with an annual incidence of 2.19±0.18% (2%–2.49%).

At the end of the study, all patients with T1DM were visited, and we did not find any new patient with DR; therefore, we confirmed that no patient had been misdiagnosed during the screening follow-up.

Statistical analysis at the end of study

In the univariate analysis (table 3), male gender, age at diagnosis HDL cholesterol and triglycerides are not significant. All other variables are significant: current age p<0.001, diabetes duration p<0.001, presence of arterial hypertension p<0.001, HbA1c p<0.001, LDL cholesterol p=0.02, creatinine p=0.012, UACR p<0.003, eGFR p<0.001 and UACR (>30 mg/g)+eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) p<0.001.

Table 3.

Statistical analysis at the end of 9-year follow-up study, based on the 366 patients with T1DM studied

| Mean values | Two-tailed Student's t-test/ANOVA | Univariate study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| No DR | 34.16±10.4 | ||

| DR | 38.6±7.85 | p=0.004, F=8.41 | p=0.004, OR 2.94 (95% CI 1.78 to 4.86) |

| Male | |||

| No DR | 46.97% | ||

| DR | 48.23% | p=0.901, OR 2.35 (95% CI 1.25 to 4.39 | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| No DR | 22.3±9.13 | ||

| DR | 21.2±8.4 | p=0.301, F=1.28 | p=0.175, OR 1.22 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.78) |

| Diabetes duration | |||

| No DR | 11.6±8.63 | ||

| DR | 17.06±9.43 | p<0.001, F=2.54 | p<0.001, OR 2.94 (95% CI 1.78 to 4.86) |

| Arterial hypertension | |||

| No DR | 9.61% | ||

| DR | 28.23% | p<0.001, OR 3.70, (95% CI 1.99 to 6.85) | |

| HbA1c | |||

| No DR | 7.76±1.6 | p<0.001, OR 2.93 (95% CI 1.57 to 5.46) | |

| DR | 9.06±1.63 | p<0.001, F=13.75 | |

| LDL | |||

| No DR | 96.74±25.55 | ||

| DR | 100.88±27.15 | p=0.005, F=1.23 | p=0.02, OR 1.28 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.89) |

| HDL | |||

| No DR | 73.91±18.93 | ||

| DR | 62.05±19.33 | p=0.525, F=0.52 | p=0.671, OR1.14 (95% CI 0.60 to 2.19) |

| Triglycerides | |||

| No DR | 96.08±41.64 | ||

| DR | 110.79±27.15 | p=0.059, F=3.59 | p=0.383, OR 0.91 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.35) |

| Creatinine | |||

| No DR | 0.77±0.16 | ||

| DR | 0.84±0.18 | p=0.002, F=2.54 | p=0.012, OR1.65 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.53) |

| UACR | |||

| No DR | 19.13±11.6 | ||

| DR | 28.38±39.24 | p=0.003, F=2.48 | p<0.001, OR 3.82 (95% CI 1.82 to 8.03) |

| eGFR | |||

| No DR | 106.11±15.62 | ||

| DR | 85.08±17.01 | p<0.001, F=1.54 | p<0.001, OR 2.23 (95% CI 0.36 to 13.58) |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; DR, diabetic retinopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; F, Fisher-Snedecor distribution; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; UACR, urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

In Cox's proportional regression analysis (table 4 and figure 1B), the introduction of different variables with DM duration as a time variable changes the univariate statistical study. Current age remains significant at p<0.001, probably due to the oldest patients having a longer duration of diabetes, therefore with more time to develop DR. Similar age at diagnosis was significant at p<0.001 with an HR value of 90.622. Gender remains not significant in the survival analysis.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis, using Cox's proportional regression analysis

| Variable | Significance HR (95% CI) | Significance HR (95% CI) | Significance HR (95% CI) | Significance HR (95% CI) | Significance HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current age | p<0.001 HR 0.736 (0.689 to 0.787) | p<0.001 HR 0.738 (0.689 to 0.789) | p<0.001 HR 0.730 (0.681 to 0.782) | p<0.001 HR 0.715 (0.665 to 0.770) | p<0.001 HR 0.762 (0.684 to 0.804) |

| Sex | p=0.871 HR 1.038 (0.658 to 1.638) | p=0.285 HR 1.305 (0.801 to 2.125) | p=0.218 HR 1.361 (0.833 to 2.222) | p=0.780 HR 1.074 (0.651 to 1.772) | p=0.073 HR 1.573 (0.668 to 1.988) |

| Age of DM diagnosis | p<0.001 HR 1.387 (1.295 to 1.485) | p<0.001 HR 1.389 (1.295 to 1.489) | p<0.001 HR 1.402 (1.305 to 1.506) | p<0.001 HR 1.432 (1.330 to 1.542) | p<0.001 HR 1.342 (1.294 to 1.665) |

| Arterial hypertension | p=0.055 HR 1.837 (0.987 to 3.421) | p=0.065 HR 1.061 (0.899 to 3.872) | p=0.096 HR 1.740 (0.907 to 3.340) | p=0.980 HR 1.009 (0.517 to 1.970) | p=0.349 HR 1.367 (0.662 to 1.899) |

| HbA1c | p<0.001 HR 4.201 (2.156 to 8.184) | p<0.001 HR 4.567 (2.305 to 9.050) | p<0.001 HR 4.819 (2.411 to 9.632) | p<0.001 HR 3.456 (1.739 to 6.868) | p<0.001 HR 2.211 (1.739 to 6.868) |

| LDL cholesterol | p<0.001 HR 0.981 (0.972 to 0.991) | p<0.001 HR 0.983 (0.974 to 0.992) | p<0.001 HR 0.984 (0.975 to 0.993) | p<0.001 HR 0.982 (0.973 to 0.992) | p=0.011 HR 0.987 (0.978 to 1.095) |

| HDL cholesterol | p=0.697 HR 1.000 (0.997 to 1.002) | p=0.747 HR 1.000 (0.997 to 1.002) | p=0.656 HR 0.999 (0.997 to 1.002) | p=0.724 HR 0.999 (0.996 to 1.003) | p=0.653 HR 0.999 (0.995 to 1.004) |

| Triglycerides | p=0.697 HR 0.999 (0.995 to 1.003) | p=0.337 HR 0.998 (0.993 to 1.002) | p=0.151 HR 0.996 (0.991 to 1.001) | p=0.166 HR 0.996 (0.990 to 1.002) | p=0.272 HR 0.997 (0.989 to 1.011) |

| Creatinine | p=0.005 HR 6.924 (1.813 to 6.450) | p=0.011 HR 5.560 (1.496 to 3.410) | p=0.287 HR 0.483 (0.127 to 1.844) | p=0.118 HR 0.937 (0.255 to 2.189) | |

| UACR | p=0.008 HR 2.354 (1.251 to 4.431) | p=0.017 HR 2.144 (1.144 to 4.018) | |||

| eGFR | p<0.001 HR 4.044 (2.716 to 6.022) | ||||

| UACR+eGFR | p<0.001 HR 3.329 (1.977 to 5.877) |

UACR+eGFR=if UACR was >30 mg/g and eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR, urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

Metabolic DM control measured by HbA1c values was a significant risk variable at p<0.001, with an HR value of 12.53. In the lipid study, LDL cholesterol remains a significant variable at p<0.001 and an HR of 13.289. No other lipid variables (HDL cholesterol or triglycerides) were significant in the survival analysis. The renal function study is interesting. Creatinine had a significant value in the univariate analysis, but not significant in the survival analysis (p=0.142). On the contrary, UACR remains a significant variable at p=0.017 in the survival analysis, but eGFR was a more significant variable than UACR at p<0.001 and an HR of 4.044, only surpassed by age at diagnosis and current age, those DM duration-dependent variables. Also the association of UACR >30 mg/g and eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were significative at p<0.001 and an HR of 3.329.

Discussion

This study should be judged in the context of previous authors’ studies.7 10 The difference between patients with T1DM and T2DM according to the incidence of any-DR, which was higher in the T1DM group with annual incidence of 15.16±2.19% compared with 8.37±2.19% in T2DM, is difficult to compare our results with other studies; there are few studies that determine incidences of DR in T1DM and T1DM in the same population. We think that most similar with our study is the Scottish National Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programme11 that reports a higher cumulative incidence in patients with T1DM (21.7%) than in those with T2DM (13.3%) in the group without DR at baseline.

The incidence of STDR was higher in patients with T1DM at 5.77±0.67% compared with 2.65±0.15% in patients with T2DM, similar values to the Scottish study.11 STDR might be due to DMO or ischaemic retina secondary to severe DR; in this study, if we subtract patients with DMO of total STDR we can conclude that 3.55% of patients with T1DM have STDR due other causes than DMO; this percentage is higher than 0.45% in patients with T2DM. Therefore, there were more patients with STDR probably due to retinal ischaemia in T1DM.

Higher STDR values in T1DM are probably due to a longer duration of DM (13.63±8.42 years in patients with T1DM compared with 8.25±6.1 years in patients with T2DM). In addition, bad metabolic control, measured by HbA1c (8.38±1.16% in patients with T1DM compared with 7.38±1.29% in patients with T2DM), causes a higher incidence of DR in patients with T1DM.

The incidence of DMO shows similar percentages in both types of DM, with a mean of 2.68±0.38% (1.71%–3.22%) in patients with T1DM and 2.22±0.19% (2%–2.49%) in patients with T2DM, despite final sum incidence was higher in patients with T1D (8.46%) than those with T2DM (6.36%).

Higher any-DR values in T1DM perhaps can be explained by two different causes: (i) a longer duration of DM (13.63±8.42 years in patients with T1DM compared with 8.25±6.1 years in patients with T2DM) and (ii) bad metabolic control measured by HbA1c (8.38±1.16% in patients with T1DM compared with 7.38±1.29% in patients with T2DM).

The incidence of any-DR according to DM was 14.7% of patients with <5 years' duration. This is important data for screening programmes, which generally include a revision at 5 years if no DR is present in T1DM, perhaps we must change review time lapse after onset of T1DM.

Also in this study, only 81.08% patients with a DM duration of >20 years developed DR. In recent studies, it is frequent to observe a decrease in the incidence of DR in this group of patients, thus the Wisconsin Diabetes Registry Study,12 which reported a 92% prevalence of any-DR, lower than previous studies such as the Wisconsin Epidemiological Study of Diabetic Retinopathy, which reported values of 97%.13 A possible explanation for these differences, shown in table 2, is that patients with DM duration of over 15 years have a better metabolic control with low levels of HbA1c.

The lipid study shows that LDL cholesterol is a risk factor in the present sample of patients. Lipid studies often create controversy, such as the Yau et al14 meta-analysis, which reported that higher total cholesterol was linked to DMO, and similar data were reported by the fenofibrate study,15 which reported slow progression and development of DR with the use of fenofibrates.

Kidney function can be evaluated by UACR or eGFR, both values being linked to DR.16 Changes in eGFR occur prior to an increase in UACR. The eGFR increases in early-stage DM and decreases in advanced stages, reflecting the decline in renal function. Recently, eGFR was determined using the CKD-EPI equation. In this study, it is evident that the eGFR is more significant than creatinine values. Furthermore, UACR seems less significant than the eGFR in Cox's survival regression (table 3). Perhaps microalbuminuria secondary to arterial hypertension or infection makes a masquerade effect in UACR. Determination of CKD-EPI equation as a reference for eGFR is recommended by various medical societies.17 A cohort study by Man et al18 reported a significant relationship between CKD-EPI values and DMO. From our data, we would encourage further studies to determine the CKD-EPI equation in patients with T1DM as an important DR risk marker.

At the end of this study, we found that 47.26% patients developed DR. These data contrast with our previously published study:10 on a sample size of 334 patients with T1DM, in which only 120 developed DR at 10 years (35.32%). The differences might be explained by methodology and the lower mean HbA1c levels in the previous study of 7.7±1.42% than this study (8.38±1.16%), probably due to a relaxation in metabolic control of patients with T1DM in recent years.10 A value of 47.26% sum incidence at 9 years is also higher than other published studies, such as Martín-Merino et al,19 based on a UK population, with a 23.9% at 9 years, and Leske et al,20 published in 2006 and based on a population in Barbados, with an incidence of 39.6%. Perhaps, higher HbA1c levels in this study might have caused these differences.

At the end of study, we revised all 366 patients to determine if any developed DR and was not reported previously during study, but we observed that no one of patients registered as normal fundus developed DR, which can demonstrate the validity of our screening programme. However, we must remember that a study of the peripheral retina can detect more lesions and can change the severity of retinopathy.21

Including patients with T1DM in a T2DM screening programme is feasible but it is important to remember that more frequent screening is difficult to achieve.

Current T2DM screening, with a mean of 4.11±0.77 visits over a 9-year period, implies that a patient visits only every 2.18 years, despite the recommendation for patients with T1DM being annual from 5 years on.22 23 Patients and clinicians should aim to make yearly retinography checks 5 years after the onset of T1DM.24

A limitation of our study is the small sample of 366 patients with T1DM and 15 030 patients with T2DM in our screened population. The number of patients with T1DM who developed DR over the 9-year follow-up period was 173 (47.26% of the sample), but the increase or decrease of only one patient can change the results in a 0.28%. The number of patients, who developed STDR, and especially DMO, is small and can bias the statistical analysis.

Strengthens of our study are (i) the screening programme, in which patients with T1DM of our area are being included; at present, there are few studies on the incidence of DR in T1DM; Lee et al25 carried out a literature review in 2015 but there were only six referenced studies of DR incidence in patients with T1DM; (ii) also, the long follow-up period of our T1DM population; and (iii) the large amount of data, such as lipid profile and GFR. It is important that future studies investigate the CKD-EPI equation, as a marker of eGFR for DR development. The increase in any-DR (47.26%) compared with our previous study (35.9%) is another important consideration, because it would seem to be linked to bad metabolic control of T1DM. If our results are confirmed by other studies in different populations, we might expect to treat a lot of complications in DR in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all paediatricians, general practitioners and endocrinologists in our area who have helped us to implement the new screening system using the non-mydriatic fundus camera, and our camera technicians for their work and interest in the diabetes screening.

Footnotes

Contributors: PRA: contributed to study conception and design, collected research data, reviewed the statistical analysis, wrote the discussion and edited the manuscript, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication. RN-G: contributed to study conception and design, contributed to ophthalmological data collection, diagnosed diabetic macular oedema, carried out the laboratory procedures, wrote the discussion and made a critical review, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication. AV-M: contributed to study design and the statistical analysis, interpreted the research data, made a critical review and reviewed the translation, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication. RS-A: contributed to study conception and design, contributed to diabetes mellitus data collection, carried out the retinographies, interpreted the research data and helped to write the manuscript, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication. AM-R: contributed to study design and the statistical analysis, interpreted research data and contributed to the interpretation of the study findings, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication. NS: contributed to ophthalmological data collection, carried out retinographies and OCT procedures and interpreted the research data, contributing to the final approval of the version sent for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by research projects FI12/01535 June 2013 and FI15/01150 July 2015 (Instituto de Investigaciones Carlos III (IISCIII) of Spain), and FEDER funds.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Hospital Universitario Sant Joan de Reus Ethics Committee [approval no. 13-01-31/proj6].

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes Atlas. 6th edn Brussels, Belgium, 2013. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2000;23(Suppl 1):S4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne RR, Jonas JB, Flaxman SR, et al. , Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe: 1990–2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:629–38. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li R, Zhang P, Barker LE, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1872–94. 10.2337/dc10-0843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. (9) Microvascular complications and foot care. Diabetes Care 2015;38:S58–66. 10.2337/dc15-S012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero P, Sagarra R, Ferrer J, et al. . The incorporation of family physicians in the assessment of diabetic retinopathy by non-mydriatic fundus camera. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;88:184–8. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero-Aroca P, de la Riva-Fernandez S, Valls-Mateu A, et al. . Changes observed in diabetic retinopathy: eight-year follow up of a Spanish population. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:1366–71. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldington SJ, Kohner EM, Meuer S, et al. . Methodology for retinal photography and assessment of diabetic retinopathy: the EURODIAB IDDM complications study. Diabetologia 1995;38:437–44. 10.1007/BF00410281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ETDRS. Detection of diabetic macular oedema study no 5. Ophthalmology 1989;9:746–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero-Aroca P, Baget-Bernaldiz M, Fernandez-Ballart J, et al. . Ten-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy and macular edema. Risk factors in a sample of people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;94:126–32. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Looker HC, Nyangoma SO, Cromie DT, et al. , Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group; Scottish Diabetic Retinopathy Collaborative. Rates of referable eye disease in the Scottish National Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programme. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:790–5. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeCaire TJ, Palta M, Klein R, et al. . Assessing progress in retinopathy outcomes in type 1 diabetes: comparing findings from the Wisconsin Diabetes Registry Study and the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2013;36:631–7. 10.2337/dc12-0863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, et al. . The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. III. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is 30 or more years. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:527–32. 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030405011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. , Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012;35:556–64. 10.2337/dc11-1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simó R, Roy S, Behar-Cohen F, et al. . Fenofibrate: a new treatment for diabetic retinopathy. Molecular mechanisms and future perspectives. Curr Med Chem 2013;20:3258–66. 10.2174/0929867311320260009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero-Aroca P, Baget-Bernaldiz M, Reyes-Torres J, et al. . Relationship between diabetic retinopathy, microalbuminuria and overt nephropathy, and twenty-year incidence follow-up of a sample of type 1 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complicat 2012;26:506–12. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. , CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Man RE, Sasongko MB, Wang JJ, et al. . The association of estimated glomerular filtration rate with diabetic retinopathy and macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:4810–16. 10.1167/iovs.15-16987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martín-Merino E, Fortuny J, Rivero-Ferrer E, et al. . Incidence of retinal complications in a cohort of newly diagnosed diabetic patients. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100283 10.1371/journal.pone.0100283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, et al. . Nine-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy in the Barbados Eye Studies. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:250–5. 10.1001/archopht.124.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Sun JK, et al. . Peripheral lesions identified by mydriatic ultrawide field imaging: distribution and potential impact on diabetic retinopathy severity. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2587–95. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diabetes (type 1 and type 2) in children and young people: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (NG18) Published date: Last updated: November 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng18/chapter/1Recommendations#type-1-diabetes

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Microvascular complications and foot care. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S72–80. 10.2337/dc16-S012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scanlon PH, Aldington SJ, Leal J, et al. . Development of a cost-effectiveness model for optimisation of the screening interval in diabetic retinopathy screening. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–116. 10.3310/hta19740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee R, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye Vis (Lond) 2015;2:17 10.1186/s40662-015-0026-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]