Abstract

There is a significant cost to mitigate the infection and inflammation associated with the implantable medical devices. The development of effective antibacterial and anti-inflammatory biomaterials with novel mechanism of action has become an urgent task. In this study, a supramolecular polymer hydrogel is synthesized by the copolymerization of N-acryloyl glycinamide and 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole in the absence of any chemical crosslinker. The hydrogel network is crosslinked through the hydrogen bond interactions between dual amide motifs in the side chain of N-acryloyl glycinamide. The prepared hydrogels demonstrate excellent mechanical properties—high tensile strength (≈1.2 MPa), large stretchability (≈1300%), and outstanding compressive strength (≈11 MPa) at swelling equilibrium state. A simulation study elaborates the changes of hydrogen bond interactions when 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole is introduced into the gel network. It is demonstrated that the introduction of 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole endowes the supramolecular hydrogels with self-repairability, thermoplasticity, and reprocessability over a lower temperature range for 3D printing of different shapes and patterns under simplified thermomelting extrusion condition. In addition, these hydrogels exhibit antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities, and in vitro cytotoxicity assay and histological staining following in vivo implantation confirm the biocompatibility of the hydrogel. These hydrogels with integrated multifunctions hold promising potential as an injectable biomaterial for treating degenerated soft supporting tissues.

Keywords: antimicrobial, high strength, self-healing, supramolecular polymer hydrogels

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Recently, great achievements have been made in the development of high strength hydrogels, placing great hope on substitution and regeneration of soft supporting tissues.[1–4] As implantable devices or bioscaffolds, the bio-materials themselves are required not to evoke the foreign body response, which is associated with the response of immune system to xenobiotics.[5–8] It has been well recognized that foreign body response can result in the failure of the implanted biomedical devices, grafts, and the discomfort of patients,[9–12] while overcoming the foreign body response to implanted biomaterials has been an immense challenge faced by the materials scientists.[13–15] To mitigate the foreign body reaction, it has been considered as the first critical step to develop a facile and versatile strategy to impart antibacterial and anti-inflammatory functions to implanted devices.[16–18] Nevertheless, high strength hydrogels with an ability to alleviate the foreign response have rarely been reported so far.

In this work, we aim to design and fabricate mechanically strong supramolecular polymer hydrogels with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory functions as future high strength implantable hydrogels for soft supporting tissue scaffolds. Our design idea is to synthesize a supra-molecular hydrogel by copolymerizing two carefully chosen monomers, N-acryloyl glycinamide (NAGA) and 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole (VTZ), without adding any chemical crosslinker. The dual amide in side chain of NAGA has been demonstrated to form stable multiple hydrogen bonding domains, serving as physical crosslinkages of this supramolecular polymer hydrogel.[19] 1,2,4-triazole and its derivatives have been recognized to exhibit diverse bioactivities such as antibacterial, antifungal, antihypertensive, and analgesic functions.[20–25] It has been demonstrated that triazole-containing derivatives could sufficiently alleviate foreign body reactions both in rodents and in nonhuman primates.[26] The use of triazole-containing monomer is expected to impart the hydrogels with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. We investigated the mechanical properties of the poly(N-arolyoyl glycinamide-co-1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole) (PNAGA-PVTZ) hydrogels, thermoplastic processability, and self-healability, which are key parameters to be considered for constructing personalized load-bearing tissue engineering scaffolds. The hydrogen bonding interaction in the supramolecular polymer network was elucidated by Gaussian calculation. The in vitro antibacterial and in vivo anti-inflammatory efficacies were also assessed.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of PNAGA-PVTZ Copolymer Hydrogels

The PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels were prepared using the following procedures. NAGA and VTZ monomers with varied molar ratios were dissolved in deionized water. Then, 2 wt% of photoinitiator IRGACURE 1173 (relative to the mass of NAGA and VTZ) was added into the monomer solution and vortexed vigorously. Subsequently, 1–1.5 mL of solution was injected into plastic rectangle molds or plastic cylinder molds. Photopolymerization was carried out for 40 min in a crosslink oven (XL-1000 UV Crosslinker, 8 W lamp with 254 nm wavelength, Spectronics Corporation, NY, USA) at room temperature. The obtained hydrogels were placed in the phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 7 d to remove the impurities. The resulting poly(N-acrolyoyl glycinamide) hydrogels were named as PNAGA-a (a represents the initial NAGA concentration) and PNAGA-PVTZ-b-c (b represents the initial monomer concentration and c represents the molar ratio of NAGA to VTZ). The weights of the initial two monomers and the dry hydrogel were measured to evaluate the monomer conversion. PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 was taken as an example. The initial two monomers, weight was 200 mg. The obtained hydrogels were washed thoroughly with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove the impurities and the unreactants, and then the hydrogels were placed in a 50 °C drying oven for 24 h. The weight of the dry hydrogel was about 199.5 mg. The monomer conversion was about 99.75%, which was calculated by dividing the weight of dry hydrogel by the weight of initial two monomers. In the same way, the monomer conversions of other hydrogels were determined to be about 99%.

Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectrometry (PerkinElmer spectrum 100, USA) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (NMR, 500 MHz, Varian INOVA) were used to characterize the successful polymerization of PNAGA hydrogels and PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels.

2.2. Self-Healability and Remoldability

The hydrogels were prepared in a glass syringe (2.0 mm diameter, 50 mm in length). The obtained hydrogel rod was fully equilibrated in PBS, and cut in the middle. After this, the two separated pieces were brought into contact with each other within the same glass syringe. The syringe was immersed in a 55 °C water bath for 45 min. The pristine hydrogel was subjected to the same condition of treatment taking into account the evaporation of water during heating. To evaluate the healing efficiency, the tensile strength of the heat-treated original hydrogel and the self-healed hydrogel were measured. The healing efficiency is defined as

| (1) |

where SH represents the tensile strength of self-healed hydrogel and S0 represents the tensile strength of heat-treated original hydrogel. The mean values and errors were calculated from at least three independent samples for each type of hydrogel.

To evaluate the repeatable thermoplastic processability and remoldability, the hydrogels were molded into a cubic shape, which was then placed into different molds. The molds were heated at 70 °C for 30 min until completion of gel to sol transition. After that, the sol in the mold was cooled down to room temperature until gel formation. Different patterned hydrogels were obtained. For visualizing purpose, the patterns were stained with rhodamine B and methylene blue.

2.3. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of the Hydrogels

The nutrient broth dilution method was used for assessing the antibacterial performance of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels.[27] Luria–Bertani broth medium (LB) was prepared according to the instructions and sterilized before use for bacterial culture. The sterilized hydrogel disks were placed in the 96-well plates. 100 μL of bacteria suspension (Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus aureus) were inoculated on the hydrogel surface. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and then the bacterial samples were dispersed in 200 μL LB medium to measure the absorbance of each well at 600 nm wavelength. Bacterial-only solution was used as a control and the relative antimicrobial efficiency (mean ± SD, n = 3) was calculated by (Abscontrol − Abssample)/Abscontrol × 100%.

2.4. In Vivo Gel Disk Implantation

All the animal experiments followed federal guidelines and were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wayne State University, U.S. C57BL/6 six-week-old male mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and randomly divided into two groups: one group was used to implant PNAGA-20 and the other group for PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 (three mice per group). Before implantation, PNAGA-20 and PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 samples were equilibrated in sterilized PBS overnight with the buffer changed three times, and then punched into disks of 5 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness. After anesthetized with isoflurane, mice were shaved and prepared with alcohol and iodine solution. A 1 cm length of incision was made on the central dorsal surface with sterilized scalpel and then bilateral subcutaneous pockets were created beside the incision. Two disks of each gel were implanted in the subcutaneous pocket. After implantation, postprocedural care was taken to ensure the recovery of the mice. All mice grew normally without body weight loss and any sign of discomfort after implantation. After one-month implantation, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. The implanted samples with surrounding tissues were collected with scissors and scalpels, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for further histological analysis. At least three sections were obtained and observed for each sample to ensure consistency between sections.

3. Results and Discussion

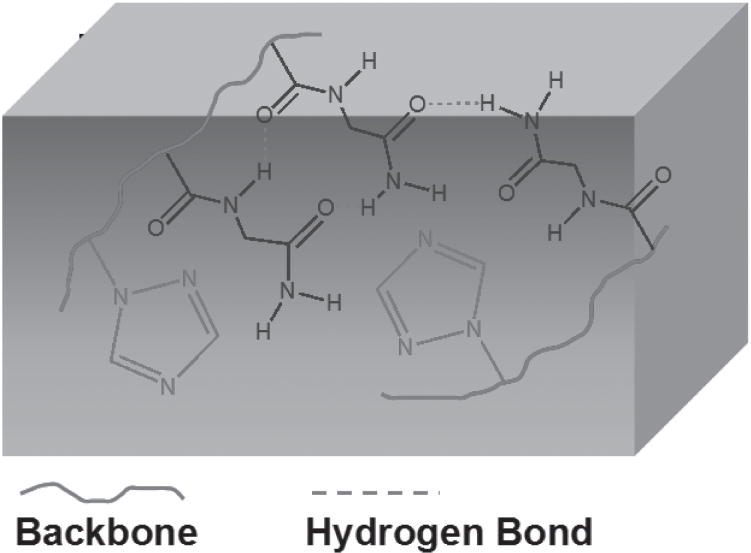

The binary supramolecular copolymer hydrogels (PNAGA-PVTZ) comprising NAGA and VTZ were prepared via photoinitiated copolymerization. The schematic diagram of copolymer hydrogel network structure is shown in Scheme 1. Figure S1 (Supporting Information) shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of the PNAGA-PVTZ copolymer hydrogels and PNAGA single component hydrogel. The three spectrograms show several identical characteristic peaks at 3071 cm−1 (N–H), 2931 cm−1 (C–H), and 1542 cm−1 (C=O, C–N, C=N),[28,29] A unique stretching vibration peak at 962 cm−1 was attributed to C–H in the ring of PVTZ, suggesting the successful incorporation of PVTZ into the copolymer hydrogel. To further verify the formation of PNAGA-PVTZ copolymer, 1H NMR spectra were recorded (Figure S2, Supporting Information). It is noted that 5 M of sodium sulfocyanate was added to disrupt the hydrogen bonds between polymer chains and dissolve the PNAGA hydrogel and PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogel in D2O. The peaks between 1.5 and 3 ppm were ascribed to the backbone protons of PNAGA and PNAGA-PVTZ units. The broad peaks within 8–9 ppm corresponded to the protons of the triazole ring presented in the copolymer.

Scheme 1.

Schematic network structure of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogel.

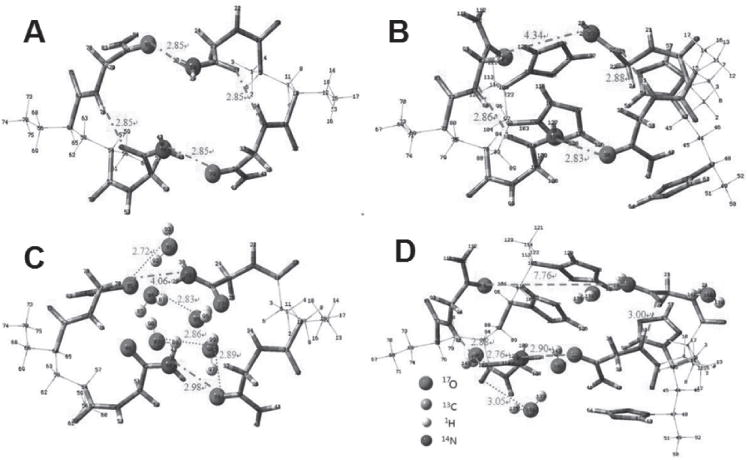

For PNAGA polymer, we previously found the formation of stable hydrogen-bonded crosslinking domains among dual amide motifs in the side chain of NAGA.[19] When hydrophilic VTZ was incorporated to form a copolymer, there is a potential concern that the hydrogen bonds between dual amides might be weakened. We did a simulation study to examine the presence of hydrogen bonds between monomer unit moieties and the impact of water on this hydrogen bonding linkage. Figure 1 compares the optimized conformation of model compounds for PNAGA dimer (PNAGA-20), 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole-co-NAGA dimer (PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10), and their mixture with 5 molecules of H2O (PNAGA-20+5H2O/PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10+5H2O) at HF/6-31g level. Table 1 shows the corresponding hydrogen bond lengths calculated by ab initio/HF. The calculated distance between carboxyl oxygen and amino nitrogen (O⋯N) was 2.85 Å for PNAGA-20 (Figure 1A). In contrast, there was only one pair of intermolecular hydrogen bond in PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 (Figure 1B), and the bond length of 38O–120N was 2.83 Å, while the other one (101O–27N) was weakened. This was attributed to the steric hindrance of 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole ring structure enlarging the interchain space in PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10. When water molecules were present in these systems, it was observed that the intermolecular hydrogen bond length of O⋯N for PNAGA-20 was increased from 2.85 to 2.98 Å for 39O–44N and from 2.85 to 4.06 Å for 81O–28N (Figure 1A,C). The increase for PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 was from 2.83 to 2.90 Å for 38O–120N, and 4.34 to 7.76 Å for 101O–27N (Figure 1B,D). The enlargement of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between polymer moieties is due to the competitive hydrogen bond formation between water molecules and the polymer, which is generally shorter than the hydrogen bond length between polymers. For example, the intermolecular hydrogen bond length of 39O–44N (between polymers) is 2.98 Å, longer than that 2.89 Å of 39O–98O (between water and polymer), and the distance of 81O–28N (between polymers) is 4.06 Å, larger than that of 2.72 Å of 81O–91O (between water and polymer) (Figure 1C). Our simulation result indicates that water tends to compete and weaken the hydrogen bonds between polymer chains with more stable hydrogen bond formation between water and polymer chains, particularly the PVTZ chain. This is consistent with the observation that more water molecules readily penetrate into PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogel system (rapid swelling) when increasing the percentage of VTZ in the copolymer. It is clearly shown that the concentrated aqueous solution of PNAGA-PVTZ starts to form the hydrogels when the monomer concentration is above 3 wt% (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Molecular conformation of A) PNAGA-20, B) PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 and C,D) their mixtures with 5 H2O optimized by ab initio. The distances of the O⋯N of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in polymer and O⋯O between water and polymer are indicated.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) for PNAGA-20, PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10, PNAGA-20+5H2O, and PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10+5H2O.

| Model compound | Hydrogen bond length [Å]

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| O⋯Na) | O⋯N′b) | O⋯O | |

| PNAGA-20 | 2.85 | – | – |

| PNAGA-20+5H2O | – | 4.06 (81O–28N) | 2.72 (81O–91O) |

| 2.98 (39O–44N) | 2.89 (39O–98O) | ||

| 2.89 (48O–72N) | 2.83 (48O–86O) | ||

| 3.03 (27O–33N) | 2.73 (27O–95O) | ||

| 2.83 (86O–95O) | |||

| 2.86 (89O–98O) | |||

| PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 | 4.34 (101O–27N) | – | – |

| 2.83 (38O–120N) | |||

| 2.86 (119O–82N) | |||

| 2.88 (26O–32N) | |||

| PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10+5H2O | – | 7.76 (101O–27N) | 3.05 (91O–134O) |

| 2.90 (38O–120N) | 2.88 (134O–142O) | ||

| 2.88 (119O–82N) | 3.43 (38O–137O) | ||

| 3.00 (26O–32N) | 2.76 (119O–146O) | ||

| 2.99 (26O–140O) | |||

Polymer

Combined with water.

Our simulation result indicates that introduction of VTZ units into the hydrogel could disturb the strong hydrogen bonding between PNAGA polymers, and allowed more water molecules to penetrate into the hydrogel network. It is expected that copolymerization of VTZ can regulate the equilibrium water contents (EWCs) of the hydrogels. Overall, EWCs of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels varied from 81% to 92% over the range of the synthetic feeding ratios we studied (Figure S4, Supporting Information). At the fixed feeding ratio, the EWCs of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels decreased when the initial monomer concentration was increased. This is attributed to the increment of hydrogen bonding density at higher monomer concentrations. Similar phenomenon was also observed with the reported PNAGA homopolymer hydrogel system. At an identical initial monomer concentration, the EWCs of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels increased with higher VTZ content. This is in agreement with our simulation result that introduction of VTZ unit lowered hydrogen bonding strength, led to the formation of looser network, and allowed more diffusion of water molecules into the network.

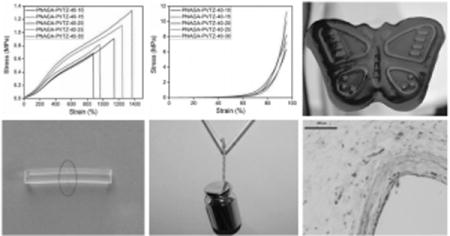

It should be noted that PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogel can reach an EWC as high as 92.3%, which is the case for PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10. Such high EWC did not seem to severely deteriorate the mechanical property of the hydrogel. The hydrogel was strong enough to bear knotting, stretching, and compression without any damage (Figure 2A–E). We have examined the tensile and compressive strengths of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels (Figure 2F–I), and found that the mechanical properties were significantly influenced by the monomer concentration and the VTZ content. At a fixed monomer concentration, increasing VTZ content led to the deterioration of mechanical properties, and at a fixed NAGA/VTZ ratio, raising NAGA content tended to enhance the mechanical performances (Figure 2 and Figure S5, Supporting Information). The number and strength of hydrogen bonds between polymer chains are the key factors affecting the mechanical properties of the networks. PNAGA-PVTZ typically had the tensile strength of 0.25–1.2 MPa, the elongation at break of 370%–1400%, and compressive strength of 2.5–12 MPa. A careful inspection of Figure 2F,G shows that some hydrogels undergo softening, hardening, and then softening stages with increasing elongation. A reasonable explanation is that at the stage of small strain, a small number of hydrogen bonds and defects start to dissociate or rupture, thus leading to a much weaker ability to withstand loading; with an increase of strain, along the axial extension, intermolecular distance is narrowed and molecular orientation may occur. In this case, more hydrogen bonds are formed to enhance the stiffness. While further increasing strain, substantial breakups occur to hydrogen bonding crosslinkage, again resulting in the declining ability to resist external loading. We note that the stress–strain curve of PNAGA-20 is the same as the previously reported one.[19] We can see that the tensile strength and elongation at break of PNAGA-20 are superior to that of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-c hydrogel (c represents the molar ratio of NAGA to VTZ) due to the partial interference of VTZ with the formation of dual amide hydrogen bonds.

Figure 2.

Deformations of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 and mechanical performances of the PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels: A) knotting, B) knotting and stretching, C–E) compression and recovery. F,H) Tensile and compressive stress–strain curves of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-c. G,I) Tensile and compressive stress–strain curves of PNAGA-PVTZ-40-c.

We further examined the swelling stability of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels at different pH. We placed the hydrogels in pH3, pH7, and pH10 buffer solutions and measured the hydrogel size change at day 1, 3, 5, and 7 (Figure S5, Supporting Information). It was generally observed that the hydrogels achieved swelling equilibrium at day 3, and would not swell more with increased incubation time. No difference in swelling behavior was observed at these pH conditions, indicating the high stability of the hydrogel no matter if placed in acidic, neutral, or basic environment. Even after incubating in the pH buffers (pH 3, 7, 10) for 7 d, the difference of tensile and compressive strengths in these buffers is still negligible (Figure S6A,B, Supporting Information).

The hydrogel was further lyophilized and reincubated in water until swelling equilibrium was achieved. We compared the mechanical strength of the hydrogel after one cycle of lyophilization with that of an as-prepared one, and no significant difference in tensile strength and breaking strain was observed (Figure S7, Supporting Information). This will be of great significance in practical applications since freeze-dried samples or products are convenient to store and transport.

The thermoplasticity and the reprocessability are of great interest in tailoring future personalized bioscaffolds. Here, a dynamic temperature sweep rheological test was performed to examine the change in the storage modulus G′ and the loss modulus G″ of representative PNAGA-20 and PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogels over a range from 30 to 85 °C. We observed that the values of G′ and G″ gradually decreased and increased, respectively, when increasing the temperature (Figure S8, Supporting Information). It should be noted that the G′ and G″ values of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel were lower than those of PNAGA-20 hydrogel due to the weakened hydrogen bonding interaction in copolymer network. For PNAGA-20 hydrogel, there was no intersection between G′ and G″ curves, implying that no gel-to-sol transition occurred. By contrast, there was an intersection point between G′ and G″ curves of the PNAGA-PVT-20-10 hydrogel at about 82 °C. An explanation is that introducing VTZ resulted in the disturbance of hydrogen bonding between PNAGA, which triggered the transition of the gel to sol.

The thermoreversible sol–gel or gel–sol transition will allow for injectability of the material for easier thermoprocessability. For example, PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel was liquefied at 60 °C, and returned the gel state when cooled down to room temperature (Figure S9, Supporting Information). PNAGA-20 hydrogel, however, remained in the gel state at 60 °C. To demonstrate its thermoprocessability, PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel was printed into different shapes or patterns with 3D printing technique under thermomelting extrusion condition (Figure S10, Supporting Information). This experiment strongly confirmed the injectability of this novel hydrogel. We expect that a PNAGA-PVTZ bioscaffold could be fabricated with 3D printing technique for potential individualized therapy.

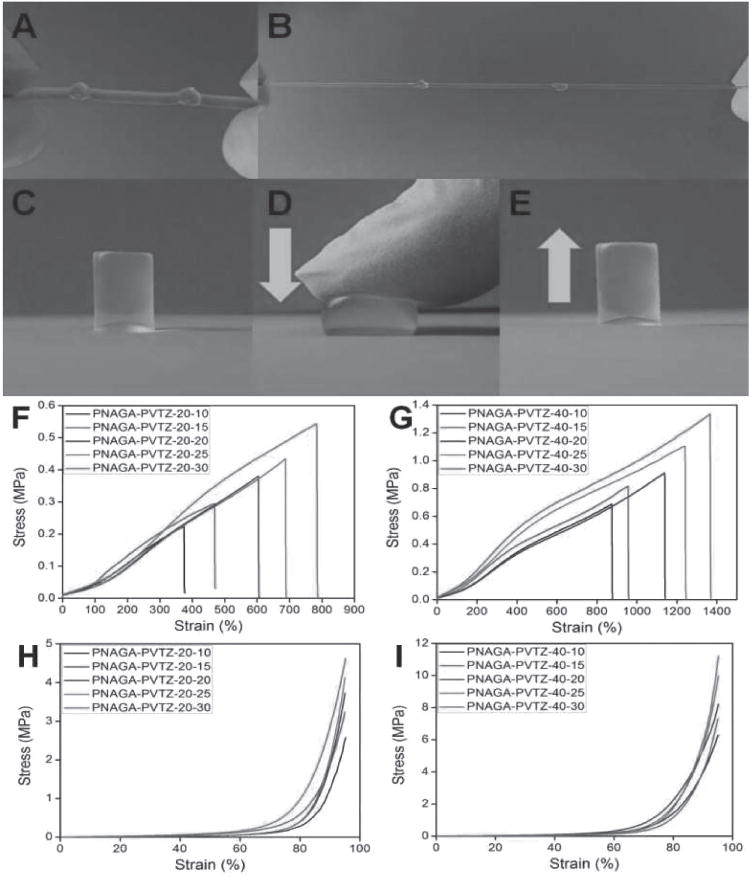

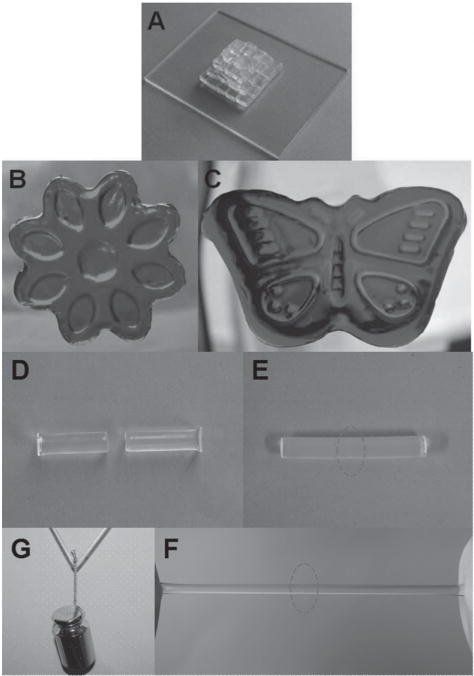

To evaluate the reprocessability of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels, PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 was sliced into small fragments with a scalpel (Figure 3A). Then, the fragments were transferred into different shaped molds and heated in a water bath for 1 h to induce gel–sol transition. After the molds were cooled down to room temperature, the hydrogel reformed into attractive flower-like and butterfly-like shapes.

Figure 3.

Photographs of the thermoplastic reprocessability and self-repairability of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel. A) Fragments of hydrogels cut with a scapel. B,C) The fragments were melted at 70 °C and remolded into a flow-like (stained with methyl orange) and butterfly-like patterns (stained with methylene blue). D) The hydrogel was cut in the middle. E) Two parts healed completely. F) The healed hydrogel could withstand stretching. G) Pulling in the middle by 100 g weight.

We further examined the heat-triggered healing ability of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels (Figure 3D–G). A cylindrical PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel was cut into two parts. The two freshly made surfaces were brought into contact within a plastic syringe under a little pressure. Then, the syringe was immersed in a 55 °C water bath for 45 min. After cooling to room temperature and demolding, the retrieved hydrogel healed completely without showing the previously cut interface, and can withstand stretching (Figure 3E,F). A healed hydrogel rod with a diameter of 5 mm can withstand a 100 g weight (Figure 3G). We have compared the tensile stress–strain curves of the pristine hydrogel and healed hydrogel (Figure S11, Supporting Information). The tensile strength ratio between the healed and pristine hydrogels was used to evaluate the self-healing efficiency (HE). The HE of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel was as high as 90%. We attributed the great self-healing capability to the dissociation and reformation of hydrogen bonds at the prebroken interface after the heating-and-cooling cycle.

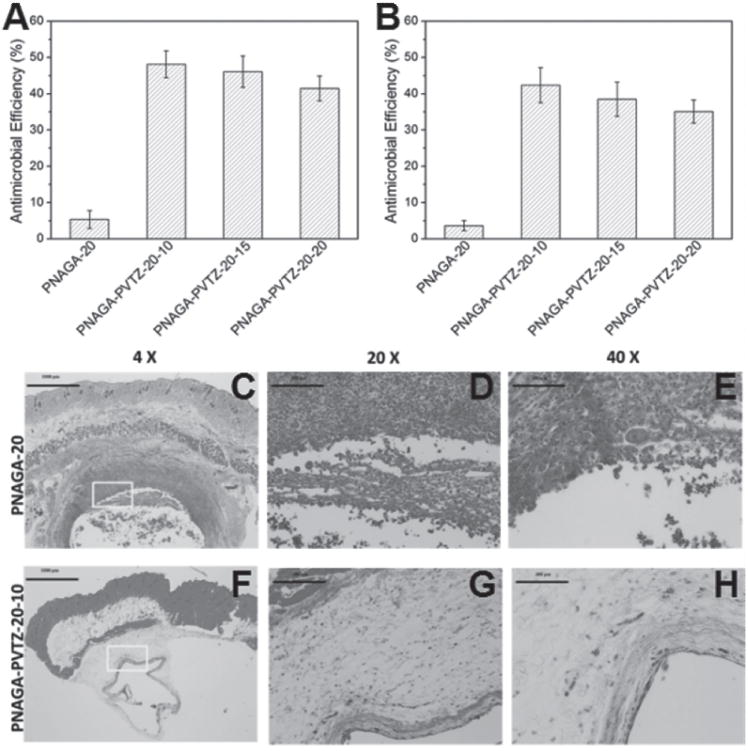

Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli strains were used to examine the antibacterial activity of PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels. PNAGA-20 hydrogel was not able to kill the bacteria, but PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels showed significant antibacterial activity against the two bacterial species, among which PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel had the best antimicrobial efficacy (Figure 4A,B). It appeared that with decreased content of VTZ, the antibacterial efficiency was gradually reduced. It has been demonstrated that the triazole ring nucleus could inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis, which damaged the permeability of the bacterial membranes and killed bacterium.[30]

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial effects of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-c hydrogels against A) E. coli and B) S. aureus. c represents various monomer ratios. Panels (C–H) are the H&E straining results of PNAGA-20 hydrogel and PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 hydrogel.

To evaluate whether PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels have bacterial killing efficacy without causing significant cell toxicity, a MTT test was used to evaluate cell viability (Figure S12, Supporting Information). The relative cell viabilities were more than 90% for all PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogels tested, suggesting their low cytotoxicity.

In vivo biocompatibility of PNAGA-20 and PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 samples were evaluated by dorsal subcutaneous implantation in the C57BL/6 mice. On gross observation after surgical operation, all mice behaved normal and no adverse events such as infection or local inflammatory response at the surgical site were observed. The microscopic reaction of the tissue surrounding the implantation site was further evaluated by the histological examination. As presented in Figure 4C, there was severe inflammation in the tissues surrounding the PNAGA-20 implanted site after 30 d of implantation. Large amount of inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, were stained in red color with H&E staining. Meanwhile, some scattered cell nucleus in sharp blue could be clearly observed (Figure 4D,E). For PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10, its implantation only induced a mild inflammatory response (Figure 4F). There were much fewer inflammatory cells surrounding PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10, suggesting its good histocompatibility. Additionally, a few fibroblasts can be observed surrounding the implantation site of PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 (Figure 4G,H). Our result indicates that PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 induced much less inflammatory response compared with PNAGA-20 after subcutaneous implantation in vivo, which is expected to be resulted from the presence of VTZ component. Since inflammatory cells are an important indicator of foreign-body reaction, we expect that PNAGA-PVTZ-20-10 may be more biocompatible than PNAGA-20.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we constructed a mechanically strong supramolecular copolymer hydrogel with integrated antimicrobial, self-healing, and thermoplastic performance. The tensile strength could change from 0.23 to 1.3 MPa through modulating the monomer ratios as well as the monomer concentration. Meanwhile, the elongation at break could reach up to more than 1300% and the compressive strength could increase to 10 MPa. The dynamic hydrogen bonding interactions endowed the hydrogel with self-repairability, reprocessability, and recyclability. The unique component of VTZ rendered the hydrogel biomaterials with medically desirable antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. The developed PNAGA-PVTZ hydrogel system can be promisingly applied as injectable hydrogels scaffolds for a variety of biomedical engineering purposes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support for this work from the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 51325305, 21274105 and 51303132), National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2016YFC1101301), Tianjin Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 15JCZD JC38000), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (1-SRA-2015-41-A-N, 2-PNF-2016-324-S-B), US National Science Foundation (DMR-1410853) and the US National Institute of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (DP2DK111910). We also appreciate Prof. Qigang Wang and Dr. Qingcong Wei of Department of Chemistry, Tongji University, for printing hydrogel using their device.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Hongbo Wang, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China.

Hui Zhu, Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202, USA.

Weigui Fu, School of Materials Science and Engineering, State Key Laboratory of Hollow Fiber Membrane, Materials and Processes, Tianjin Polytechnic University, Tianjin 300387, China.

Yinyu Zhang, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China.

Bing Xu, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China.

Fei Gao, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China.

Zhiqiang Cao, Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202, USA.

Wenguang Liu, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Composite and Functional Materials, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China.

References

- 1.Nonoyama T, Wada S, Kiyama R, Kitamura N, Mredha MTI, Zhang X, Kurokawa T, Nakajima T, Takagi Y, Yasuda K, Gong JP. Adv Mater. 2016;28:6740. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao F, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xu B, Cao Z, Liu W. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:8956. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu B, Zheng P, Gao F, Wang W, Zhang H, Zhang X, Feng X, Liu W. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1604327. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang L, Liu W, Liu G. Adv Mater. 2010;22:2652. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman DL, King RN, Andrade JD. J Biomed Mater Res. 1974;8:199. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols SP, Koh A, Brown NL, Rose MB, Sun B, Slomberg DL, Riccio DA, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avula MN, Rao AN, Mcgill LD, Grainger DW, Solzbacher F. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9737. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward WK, Slobodzian EP, Tiekotter KL, Wood MD. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4185. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer R, Park K. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3235. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grainger DW. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:507. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DF. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2941. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding JL, Reynolds MM. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32:140. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye Q, Harmsen MC, Luyn MJAV, Bank RA. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9192. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward WK. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:768. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swartzlander MD, Bames CA, Blakney AK, Kaar JL, Kyriakides TR, Bryant SJ. Biomaterials. 2015;41:26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Cao ZQ, Bai T, Carr L, Ella-Menye JR, Irvin C, Ratner BD, Jiang SY. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:553. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratner BD. J Controlled Release. 2002;78:211. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones DH, Slack R, Squires S, Woolridge KRH. J Med Chem. 1965;8:676. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai X, Zhang Y, Gao L, Bai T, Wang W, Cui L, Liu W. Adv Mater. 2015;27:3566. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katica CR, Vesna D, Vlado K, Dora GM, Aleksandra B. Molecules. 2001;6:815. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sztanke K, Tuzimski T, Rzymowska J, Pasternak K, Szerszen MK. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:404. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijesh AM, Isloor AM, Shetty P, Sundershan S, Fun HK. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;62:410. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezabadi IR, Camoutsis C, Zoumpoulakis P, Geronikaki A, Soković M, Giamocilija J, Cirić A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:1150. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumrra SH, Chohan ZH. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2013;28:1291. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.735666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almajan GL, Barbuceanu SF, Almajan ER, Draghicj C, Saramet G. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:3083. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vegas AJ, Veiseh O, Doloff JC, Ma M, Tam HH, Bratlie K, Li J, Bader AR, Langan E, Olejnik K, Fenton P, Kang JW, Hollister-Locke J, Bochenek MA, Chiu A, Siebert S, Tang K, Jhunjhunwala S, Aresta-Dasilva S, Dholakia N, Thakrar R, Vietti T, Chen M, Cohen J, Siniakowicz K, Qi M, McGarrigle J, Lyle S, Harlan DM, Greiner DL, Oberholzer J, Weir GC, Langer R, Anderson DG. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu B, Li Y, Gao F, Zhai X, Sun M, Lu W, Cao Z, Liu W. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:16865. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b05074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seuring J, Agarwal S. Macromol Chem Phys. 2010;211:2109. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayramgil NP. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012;97:182. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson EM, Warnock DW, Luker J, Porter SR, Scully C. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:103. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.