Reduction of CO2 to methanol using renewable hydrogen is a promising but challenging strategy for carbon capture and utilization.

Abstract

Although methanol synthesis via CO hydrogenation has been industrialized, CO2 hydrogenation to methanol still confronts great obstacles of low methanol selectivity and poor stability, particularly for supported metal catalysts under industrial conditions. We report a binary metal oxide, ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst, which can achieve methanol selectivity of up to 86 to 91% with CO2 single-pass conversion of more than 10% under reaction conditions of 5.0 MPa, 24,000 ml/(g hour), H2/CO2 = 3:1 to 4:1, 320° to 315°C. Experimental and theoretical results indicate that the synergetic effect between Zn and Zr sites results in the excellent performance. The ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst shows high stability for at least 500 hours on stream and is also resistant to sintering at higher temperatures. Moreover, no deactivation is observed in the presence of 50 ppm SO2 or H2S in the reaction stream.

INTRODUCTION

Global environmental changes caused by huge amounts of anthropogenic CO2 emissions have become a worldwide concern. However, CO2 is an abundant and sustainable carbon resource. It is highly desired to develop technologies to convert CO2 into valuable chemicals. Among the strategies considered, catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol using the hydrogen from renewable energy sources has received much attention, because methanol not only is an excellent fuel but also can be transformed to olefins and other high value-added chemicals commonly obtained from fossil fuels (1).

Much progress has been made in the development of supported metal catalysts for CO2hydrogenation, such as Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 (2–10), Cu/ZrO2 (2–5, 11–13), and Pd/ZnO (2–5, 14, 15). Among these, the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst was the most efficient and has been extensively studied. However, one of the problems for these catalysts is the low methanol selectivity caused by reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction. The even more severe problem is the rapid deactivation caused by produced water, which accelerates the sintering of Cu active component during the CO2 hydrogenation (16). Although more efficient “georgeite” Cu-based catalyst (17), Cu(Au)/CeOx/TiO2 (18, 19), and Ni(Pd)-Ga (20–22) catalysts have been reported, the selectivity toward methanol is lower than 60% under their reported conditions. Recently, higher methanol selectivity is reported for In2O3 (23–25). However, this is compromised by low CO2 conversion (25). Up to now, we are still lacking an efficient catalyst that enables a CO2 hydrogenation conversion above 10% with high methanol selectivity and stability to fulfill the requirements of large-scale production under industrial operation conditions. Here, we report a ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst, which shows methanol selectivity of 86 to 91% at a CO2 conversion of more than 10% under the conditions of 5.0 MPa, 24,000 ml/(g hour), H2/CO2 = 3:1 to 4:1, 320° to 315°C, demonstrated with a fixed-bed reactor. The catalyst shows excellent stability for more than 500 hours on stream, and it is promising for the conversion of CO2 to methanol in industry.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

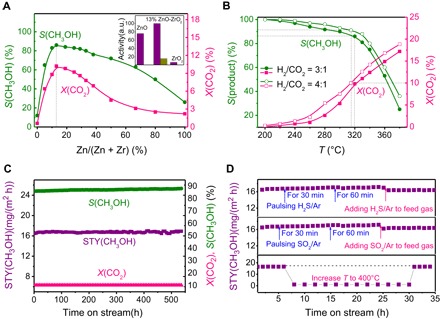

A series of x% ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts (x% represents molar percentage of Zn, metal base) were prepared by the coprecipitation method, and their catalytic performances were investigated as shown in Fig. 1. ZrO2 shows very low activity in methanol synthesis. ZnO shows a little activity and low methanol selectivity (table S1). However, the performance of the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst varies greatly with the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio (Fig. 1A). The catalytic activity is significantly enhanced and reaches the maximum for CO2 conversion when the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio is close to 13%. This is also where the methanol selectivity (mainly methanol and CO as the products) is approaching the maximum (fig. S1). Therefore, the highest space-time yield (STY) of methanol is achieved for the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst at the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio of 13%, and hereafter, it represents the optimized catalyst. It is worth noting that the CO2 conversion of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is about 1.3 and 14 times of those for ZnO and ZrO2, respectively, and the methanol selectivity is increased from no more than 30% for ZnO or ZrO2 to more than 80% for 13% ZnO-ZrO2. More interestingly, the activity of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is about six times of that for mechanically mixed ZnO and ZrO2 in the same composition as 13% ZnO-ZrO2 (inset in Fig. 1A), indicating that there is a strong synergetic effect between these two components in the catalytic activity of CO2 hydrogenation.

Fig. 1. Catalytic performance of the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst.

(A) Dependence of catalytic performance at 320°C on the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio. Inset: purple, normalized activities for ZnO, 13% ZnO-ZrO2, and ZrO2 by specific surface area; dark yellow, normalized activities for mechanically mixed ZnO and ZrO2 in the same composition. (B) Catalytic performance at the reaction temperatures from 200° to 380°C with H2/CO2 = 3:1 and 4:1. (C) Catalyst stability test in 550 hours. (D) Catalyst stability toward the S-containing molecules (50 ppm H2S or SO2 in Ar) and annealing. In S experiments, there are two gas paths: one is 50 ppm H2S(SO2)/Ar and the other is CO2/H2/Ar. Pulsing experiment was carried out by turning on the S gas for 30 min and 60 min and then turning off after the CO2 + H2 reaction reached its steady state. After several pulses, the two gas paths were turned on simultaneously. Standard reaction conditions: 5.0 MPa, H2/CO2 = 3:1, 320°C, GHSV = 24,000 ml/(g hour), using a tubular fixed-bed reactor with the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst.

Figure 1B shows that when increasing the reaction temperature, the selectivity of methanol decreases, whereas the conversion of CO2 increases. When the conversion reaches 10% at 320°C, the selectivity of methanol can still be kept at 86%. Higher pressure, gas hourly space velocity (GHSV), and H2/CO2 ratio are beneficial to the methanol selectivity (fig. S2). Methanol selectivity can be as high as 91% when H2/CO2 is increased to 4:1 with a CO2 conversion of 10% at 315°C.

Figure 1C shows that there is no deactivation of the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst in CO2 hydrogenation, and no deterioration in methanol selectivity for more than 500 hours on stream at least. Stability is a fatal issue for methanol synthesis from either CO or CO2 hydrogenation on most supported metal catalysts because most methanol synthesis catalysts are easily deactivated at higher temperatures due to the sintering effect. To further test the thermal stability of the catalyst, the reaction temperature was elevated from 320° to 400°C, kept for 24 hours, and then cooled down to 320°C. No deactivation is observed after this annealing treatment. To our surprise, this catalyst also shows the resistance to sulfur-containing molecules in the stream with 50 parts per million (ppm) SO2 or H2S (Fig. 1D). The sulfur-containing molecules are always present in CO2 sources from flue gas produced from coal or biomass burning. Therefore, the high stability of the catalyst toward the sulfur-containing molecules makes the catalyst viable in industrial processes and superior to supported metal catalysts.

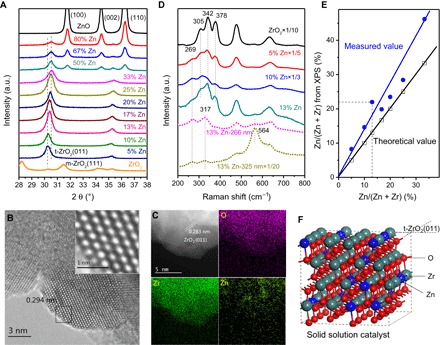

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns show that the ZrO2 prepared by the coprecipitation method is mainly in the monoclinic phase mixed with some in the tetragonal phase (Fig. 2A and fig. S3). Adding ZnO (5 to 33%) to ZrO2 leads to the phase change of ZrO2 from monoclinic to tetragonal or cubic (not distinguishable from tetragonal). The phase of ZnO was detected for samples with ZnO concentrations of up to 50%, indicating that the ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution might be formed with ZnO contents in the range below 50%. The interplanar spacing of 13% ZnO-ZrO2, which is ca. 0.29 nm (Fig. 2B and fig. S4), is attributed to the tetragonal ZrO2 (011). However, element distribution analysis shows that Zn is highly dispersed in ZrO2 (Fig. 2C). Considering that the ionic radius of Zn2+ (0.74 Å) is smaller than that of Zr4+ (0.82 Å) (26), the interplanar spacing would be decreased when Zn2+ is incorporated into the lattice of ZrO2. This is confirmed with the XRD results that the (011) spacing of ZrO2 narrows, and the XRD from the (011) spacing of ZrO2 shifts to a higher angle when the Zn concentration is increased from 5 to 33%. These facts further affirm the conclusion that ZnO-ZrO2 is in a solid solution state, with Zn incorporated into the ZrO2 lattice matrix (27).

Fig. 2. Structural characterization of the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst.

(A) XRD patterns of ZnO-ZrO2. (B) High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and (C) aberration-corrected scanning TEM–high-angle annular dark-field images and element distribution of 13% ZnO-ZrO2. (D) Raman spectra of ZnO-ZrO2 with 244-nm laser (solid line), 266-nm laser (pink dot line), and 325-nm laser (dark yellow dot line). (E) Zn concentration in the surface region of ZnO-ZrO2 measured by XPS. (F) Schematic description of the ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst model.

Raman spectroscopy was used to further characterize the phase structure of the ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst. Raman spectroscopy with different laser sources could detect phases in different depths due to light absorption and light scattering {I∝(1/λ)4}. ZnO-ZrO2 exhibits a strong ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption band at 215 nm (fig. S5A), so the shorter wavelength laser detects the phase in a relatively shallow layer. Therefore, the Raman spectroscopy with laser sources at 244, 266, and 325 nm could gradually detect phases from the skin layer to the bulk of the catalyst (fig. S5B) (28, 29). The phase near the utmost skin layer (the depth of skin layer is approximately 2 nm) is sensitively detected by UV Raman spectroscopy with a 244-nm excitation laser, as shown in Fig. 2D. The appearance of Raman peaks at 305, 342, and 378 cm−1 indicates that the skin layer of pure ZrO2 is in monoclinic. For 5 to 13% ZnO-ZrO2 samples, when increasing the ZnO content from 5 to 13%, the spectrum evolved slightly from that of the monoclinic phase to one with an additional peak at 269 cm−1, although the peaks in the range of 300 to 500 cm−1 are similar to those of ZrO2. The weak peak at 269 cm−1 is due to the characteristics of the tetragonal phase (30, 31). This suggests that the skin layer phase of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 might be in the transition state between monoclinic and tetragonal phases. The Raman spectrum with a 266-nm laser is dominated by peaks at 269 and 317 cm−1 (Fig. 2D and fig. S5, C and D), which are due to the tetragonal phase of ZrO2, and the Raman spectrum with a 325-nm laser gives a typical peak at 564 cm−1 due to the cubic phase. These results suggest that underneath the skin layer of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is in the tetragonal phase, whereas the bulk is in the cubic phase. Note that the Raman signal of the monoclinic phase is much stronger than that of tetragonal and cubic phases. Therefore, the distorted phase in the surface region could be obscured by the monoclinic phase in Raman spectra. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results show that the Zn concentration in the surface region is higher than the theoretical value (Fig. 2E), suggesting that Zn is relatively rich there. These facts indicate that the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst is an imperfect solid solution in phase transition from skin layer to bulk, as schematically depicted in Fig. 2F.

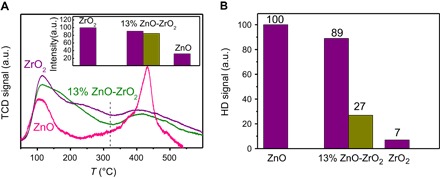

CO2-TPD (temperature-programmed desorption of CO2) of catalysts shows that there are two desorption peaks: low (<320°C) and high (>320°C) temperature (Fig. 3A). The total CO2 adsorption amounts for ZrO2, 13% ZnO-ZrO2, and ZrO2 are 100, 82, and 82 mmol/m2, respectively. CO2 absorption capability below the reaction temperature, 320°C, follows the order ZrO2 (100) > 13% ZnO-ZrO2 (91) >> ZnO (32) (inset in Fig. 3A). ZrO2 adsorbs much more CO2 than does ZnO below the reaction temperature. Furthermore, the surface component of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is about 78% Zr and 22% Zn obtained from XPS (Fig. 2E), and the amount of adsorbed CO2 on ZnO-ZrO2 is about the same as that estimated from the sum of the amounts of CO2 adsorbed on the individual components based on that normalized by specific surface area (inset in Fig. 3A). Therefore, it could be deduced that, at low temperatures, most of the CO2 adsorbed by 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is on the Zr sites.

Fig. 3. CO2 adsorption and H2 activation.

(A) CO2-TPD on ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2 normalized by specific surface area. Inset: purple, normalized CO2 adsorption below 320°C; dark yellow, normalized activities for mechanically mixed ZnO and ZrO2 in the same composition as 13% ZnO-ZrO2. (B) H2-D2 exchange reaction on ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2 at 280°C. Purple, normalized rate by specific surface area; dark yellow, normalized activities for mechanically mixed ZnO and ZrO2 in the same composition as 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

The rate of HD formation from the H2-D2 exchange reaction normalized by specific surface area is as follows: ZnO (100) > 13% ZnO-ZrO2 (89) >> ZrO2 (7) (Fig. 3B), indicating that ZnO has much higher activity in the H2-D2 exchange reaction than ZrO2. Surprisingly, the activity of 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is also much greater than that of ZrO2, although ZrO2 comprises 78% of the catalyst’s specific surface area. If the two components kept their own activity in the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst, the sum of their activities would be about 27, far less than the experimental result, which is 89. This suggests that there is a strong synergetic effect in the H2 activation between the two sites, Zn and Zr. XPS shows that the binding energy of Zn in 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is evidently reduced compared to that of ZnO, whereas the binding energy of Zr in 13% ZnO-ZrO2 remains intact (fig. S6). This indicates that the electronic property of the Zn site is modified by the neighboring Zr site. H2-TPR (temperature-programmed reduction of H2) also shows that 13% ZnO-ZrO2 is more easily reduced than ZnO and ZrO2 (fig. S7). Therefore, on the basis of the H2-D2 exchange reaction and catalytic CO2 hydrogenation reaction results, we could conclude that it is the synergetic effect between the Zn and Zr sites in the ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst that significantly promotes the activation of H2 and CO2 and consequently results in the excellent catalytic performance in CO2 hydrogenation. This is also shown experimentally from the fact that the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst exhibits much higher activity and methanol selectivity than does mechanically mixed ZnO + ZrO2 (13:87) or the supported 13% ZnO/ZrO2 catalyst in CO2 hydrogenation (Fig. 1A, table S2, and fig. S8).

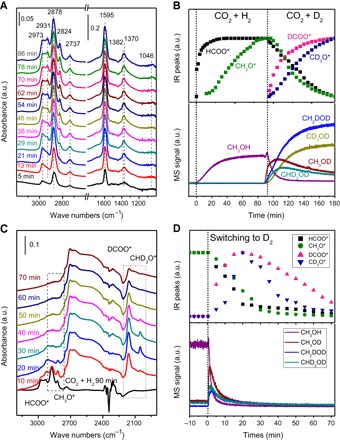

To understand the reaction mechanism on the solid solution catalyst, the surface species evolved in the reaction were monitored by in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) (Fig. 4A). HCOO* and H3CO* species were observed and identified (table S3) (32–37). The infrared (IR) peaks at 1595 and 1370 cm−1 are assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric OCO stretching vibrations, respectively, of adsorbed bidentate HCOO* species. The peaks at 2878 and 1382 cm−1 are assigned to the stretching vibration ν(CH) and bending vibration δ(CH), respectively. The peaks at 2931, 2824, and 1046 cm−1 are attributed to the H3CO* species. The peaks at 2878 and 2824 cm−1 were used to follow the concentration changes of HCOO* and H3CO* species. Figure 4B shows the varying tendency of the two species with time, and the products were detected by mass spectrometry (MS) (38). It can be seen that the surface HCOO* (based on IR peak intensity) reaches a steady state after a reaction for 30 min, whereas it takes 90 min for H3CO* to reach its steady state. However, CH3OH detected by MS reaches a steady state after 60 min. When CO2 + H2 was substituted for CO2 + D2, the amount of HCOO* and CH3OH decreases (Fig. 4B and fig. S9), whereas the amount of DCOO* and CD3OD increases. The DCOO* species appears and reaches a steady state after ca. 90 min; meanwhile, the total D-substituted products reach a steady state after ca. 90 min, as detected by MS. It is speculated that the HCOO* and CH3O* species are likely intermediates of the CO2 hydrogenation on the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst. To verify the possible surface intermediate species, the IR spectra of surface species formed from CO2 + H2 were recorded as those in Fig. 4A, then the reaction gas phase of CO2 + H2 was switched to D2, and the IR peaks at 2878 and 2824 cm−1 of the HCOO* and H3CO* species, respectively, are declined rapidly and disappeared in 60 min (Fig. 4C). Correspondingly, two new peaks at 2165 and 2052 cm−1 due to the DCOO* and HD2CO* species appeared first, grew somewhat, and then disappeared slowly. MS displays the HD2COD product responding to the disappearance of the surface HCOO* and H3CO* species at the same time (Fig. 4D). These evidences indicate that the surface HCOO* and H3CO* species on the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst can be hydrogenated to methanol.

Fig. 4. Characterization of surface species.

(A) In situ DRIFT spectra of surface species formed from the CO2 + H2 reaction. (B) DRIFT-MS of CO2 + H2 and CO2 + D2 reactions on 13% ZnO-ZrO2. (C) In situ DRIFT spectra of surface species from CO2 + H2 and subsequently switched to D2. (D) DRIFT-MS of CO2 + H2 and subsequently switched to D2. Reaction conditions: 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst, 0.1 MPa, 280°C, 10 ml/min CO2 + 30 ml/min H2 (D2).

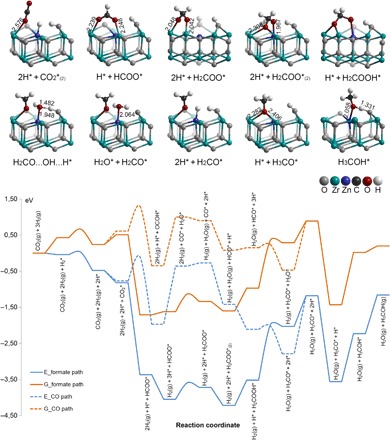

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to understand the reaction mechanisms (details in the Supplementary Materials). Figure 5 shows the reaction diagram of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on the surface of ZnO-ZrO2. Two major reaction pathways were evaluated, that is, formate and CO pathways (39, 40). H2 is adsorbed and dissociated on the Zn site. CO2 is adsorbed on the coordination unsaturated Zr site (figs. S10 to S12). The formation of HCOO* species via CO2* hydrogenation is energetically very favorable, which is coherent with the in situ DRIFTS observations. The terminal oxygen of H2COO* (formed by HCOO* hydrogenation) can be protonated by an OH* group and forms a H2COOH* species, of which the C-O bond is cleaved and thereby generates H2CO* and OH* binding on Zr and Zn sites, respectively. The process of H2COO* → H2CO* + H2O* is thermodynamically unfavorable (ΔrG = 1.26 eV). The desorption energy of water from the surface is 0.60 eV. H2CO* + H* → H3CO* is an energetically favorable process (ΔrG‡ = −2.32 eV). H3CO* species identified by theoretical calculation corresponds to the second most stable reaction intermediate detected by in situ DRIFTS. Finally, methanol is formed by H3CO* protonation.

Fig. 5. DFT calculations.

Reaction diagram [energy (E) and Gibbs free energy (G) at a typical reaction temperature of 593 K] of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on the (101) surface of the tetragonal ZnO-ZrO2 model.

In principle, it is also possible to first produce CO* from CO2* and then for CO* to undergo consecutive hydrogenation to form methanol. As shown in Fig. 5, OCOH* is much less stable than HCOO*. Furthermore, the reaction of CO2* to OCOH* needs to overcome a barrier (ΔG‡) of 0.69 eV, which is quite unfavorable compared to the barrier-less process of CO2* + H* → HCOO*. Even if a fair amount of OCOH* can be present during the reaction, the weakly bonded CO* produced from OCOH* prefers to desorb from the surface rather than undergo hydrogenation reactions. Therefore, it is concluded that CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on the surface of ZnO-ZrO2 is through the formate pathway.

DFT calculations also suggest that the methanol selectivity of ZnO-ZrO2 is higher than that of ZnO (41, 42). The formate pathway was evaluated on ZnO for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol (figs. S13 to S16). The process of H2COO* → H2CO* + H2O* is the most unfavorable step in thermodynamics. The energy barrier of this step is 1.37 eV, higher than that for ZnO-ZrO2 (1.27 eV). Therefore, ZnO-ZrO2 has a relatively higher methanol selectivity and a lower CO selectivity than ZnO. The results are consistent with the experimental results as well. The high methanol selectivity of ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution is attributed to the synergetic effect in H2 activation between the Zn and Zr sites, and the simultaneous activation of H2 and CO2 on the neighboring sites, Zn and Zr, respectively.

There has been an opinion that the CO2 hydrogenation is similar to the CO hydrogenation, and the pathway of CO2 to methanol is a CO pathway, where it is assumed that CO2 hydrogenation to methanol is first to CO (by RWGS) and then the CO is hydrogenated to methanol (13, 18). To clarify this issue, the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst was also evaluated for CO + H2 (fig. S17). Besides methanol as the major product, some additional products including dimethyl ether (DME) and methane were detected. The STY of methanol on the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst from CO2 hydrogenation is 2.5 times of that from CO hydrogenation at their optimized temperatures for methanol production. These facts indicate that the ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst is especially active for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol.

Whether formate species are involved in the methanol synthesis for Cu-based catalysts has been a controversial issue. For example, the latest reports on Cu/ZrO2 from Larmier et al. (12) and Kattel et al. (13) proposed very different mechanisms. According to the former, formate species was the reaction intermediate, whereas the latter stated that formate was a spectator. Very recently, Kattel et al. (10) proposed that the formate was an intermediate species for methanol on the Cu/ZnO catalyst. Because our ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst is very different from the Cu-based one, the methanol formation mechanism might also be different. Our isotope labeling experiment and DFT calculation show that the formate species can be hydrogenated to methanol. However, at the moment, we still could not reach the conclusion that the formate species is the major active intermediate for methanol formation because it is difficult to determine how much of the observed formate species contributed to the methanol production.

To compare the catalytic performance difference between the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst and Cu-based catalysts, a standard Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst was evaluated for CO2 hydrogenation. The methanol selectivity varies from 82 to 5% at reaction temperatures from 200° to 320°C under identical conditions as those used for the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst (fig. S18). The results are similar to those reported for the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst in the literature (43, 44). It is seen that the selectivity of methanol on the Cu-based catalyst is lower than that on the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst and markedly decreases when the reaction temperature was elevated. In addition, the stability of the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst was tested for sintering and sulfur poisoning (fig. S19). The activity of the catalyst shows a decrease of 25% for the reaction in 500 hours, and the activity drops even more quickly in the presence of 50 ppm SO2; however, the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst does not show any deactivation in 500 hours and SO2 does not change the activity obviously either (Fig. 1, C and D). A controlled experiment demonstrated that the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst was deactivated severely (at least 25% drop in activity) after a thermal treatment at 320°C, whereas the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst does not show evident deactivation after a thermal treatment even at 400°C (Fig. 1D).

This work demonstrates that the binary metal oxide ZnO-ZrO2 in the solid solution state is an active catalyst for converting CO2 to methanol with high selectivity and stability. This solid solution catalyst opens a new avenue for CO2 conversion by taking advantage of the synergetic effect between its multicomponents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Catalyst preparation

The 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst was taken as a typical example to describe the synthesis procedures: 0.6 g of Zn(NO3)2 · 6H2O and 5.8 g of Zr(NO3)4 · 5H2O were dissolved in a flask by 100 ml of deionized water. The precipitant of the 100-ml aqueous solution of 3.06 g of (NH4)2CO3 was added to the aforementioned solution (at a flow rate of 3 ml/min) under vigorous stirring at 70°C to form a precipitate. The suspension was continuously stirred for 2 hours at 70°C, followed by cooling down to room temperature, filtering, and washing three times with deionized water. The filtered sample was dried at 110°C for 4 hours and calcined at 500°C in static air for 3 hours. Other x% ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts were prepared following the same method. The supported ZnO/ZrO2 catalyst was prepared by wet impregnation. ZrO2 support was synthesized according to the coprecipitation method described above. ZrO2 (1 g) was immersed in 25 ml of aqueous solution of Zn(NO3)2 with stoichiometric amount. The mixture was stirred at 110°C until the water had completely volatilized and then calcined at 500°C in air for 3 hours. The Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst was prepared by coprecipitation analogous to the procedure described by Behrens and Schlögl (6). Aqueous solution (100 ml) of metal nitrates [4.35 g of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, 2.68 g of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, and 1.12 g of Al(NO3)3·9H2O] and aqueous solution (120 ml) of 3.82 g of Na2CO3 as a precipitant were added dropwise (at a flow rate of 3 ml/min) to a glass reactor with a starting volume of 200 ml of deionized water under vigorous stirring at 70°C. Controlling the pH of precipitation mother liquor to 7, and aging the precipitate for 2 hours after precipitation, followed by cooling down to room temperature, filtering, and washing seven times with deionized water. The filter cake was dried at 110°C for 4 hours and calcined at 350°C in static air for 3 hours. The commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst (C307) was purchased from Nanjing Chemical Industrial Corporation of Sinopec for comparison. All catalysts were pressed, crushed, and sieved to the size of 40 to 80 mesh for the activity evaluation.

Catalyst evaluation

The activity tests of the catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol were carried out in a tubular fixed-bed continuous-flow reactor equipped with gas chromatography (GC). Before the reaction, the catalyst (0.1 g, diluted with 0.4 g of quartz sand) was pretreated in a H2 or N2 stream (0.1 MPa and 20 ml/min) at given temperatures. The reaction was conducted under reaction conditions of 1.0 to 5.0 MPa, 180° to 400°C, V(H2)/V(CO2)/V(Ar) = 72:24:4, 64:32:4, or 77:19:5, and GHSV = 5000 to 33,000 ml/(g hour). The exit gas from the reactor was maintained at 150°C and immediately transported to the sample valve of the GC (Agilent 7890B), which was equipped with thermal conductivity (TCD) and flame ionization detectors (FIDs). Porapak N and 5A molecular sieve packed columns (2 m × 3.175 mm; Agilent) were connected to TCD, whereas TG-BOND Q capillary columns were connected to FID. The packed column was used for the analysis of CO2, Ar, and CO, and the capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 10 μm; Thermo Fisher) was used for hydrocarbons, alcohols, and other C-containing products. CO2 conversion [denoted as X(CO2)] and the carbon-based selectivity [denoted as S(product)] for the carbon-containing products, including methane, methanol, and DME, were calculated using an internal normalization method. STY of methanol was denoted as STY(CH3OH). All data were collected in 3 hours after the reaction started (unless otherwise specified).

X(CO2), S(CH3OH), S(CO), and STY(CH3OH) were calculated as follows:

Catalyst characterization

The XRD results were collected on a Philips PW1050/81 diffractometer operating in Bragg-Brentano focusing geometry and using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) from a generator operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. TEM images were obtained with a JEM-2100 microscope at 200 kV. The samples were prepared by placing a drop of nanoparticle ethanol suspension onto a lacey support film and by allowing the solvent to evaporate. Element mappings were obtained with a JEM-ARM200F microscope. UV-vis spectrum was obtained with a PerkinElmer 25 UV-vis spectrometer in the wavelength range of 350 to 800 nm, with a resolution of 1 nm. The UV laser source (244 and 266 nm) was a Coherent Innova 300 C FreD continuous wave UV laser equipped with an intracavity frequency-doubling system using a BBO crystal to produce second harmonic generation outputs at different wavelengths. The UV laser source (325 nm) was a Coherent DPSS 325 Model 200 325-nm single-frequency laser. UV Raman spectra were recorded on a home-assembled UV Raman spectrograph using a Jobin-Yvon T64000 triple-stage spectragraph with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1 coupled with a UV-sensitive charge-coupled device detector. XPS was performed using a Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi with Al K radiation (15 kV, 10.8 mA, hν = 1486.6 eV) under ultrahigh vacuum (5 × 10−7 Pa), calibrated internally by the carbon deposit C(1s) (Eb = 284.6 eV). The CO2/H2-TPD of the catalysts was conducted with an adsorption/desorption system. A 100-mg sample was treated in situ in a H2 or He stream (30 ml/min) at 300°C for 1 hour, flushed by a He stream (30 ml/min) at 300°C for 30 min to clean its surface, and then cooled to 50°C. It was then returned to the CO2/H2 stream for 60 min, and afterward, the sample was flushed by the He stream until a stable baseline was obtained. TPD measurements were then conducted from 50° to 600°C. The temperature increase rate was 10°C/min. The changes of CO2/H2 were monitored by AutoChem 2910 with a TCD detector. The system was coupled to an OmniStar 300 mass spectrometer to detect other products in the gas phase. The TPR of the catalysts was conducted with the same system used in TPD. The samples were treated with He at 130°C for 1 hour, and then 5% H2/Ar was used as carrier gas of TCD to conduct the TPR with 10°C/min from 50° to 800°C. H2-D2 exchange experiments were performed in a flow reactor at 280°C. The formation rate of HD was measured by mass signal intensity (ion current). The 0.1-g sample was reduced with H2 (10 ml/min) at 280°C for 1 hour. Then, D2 (10 ml/min) was mixed with H2 and together passed the catalyst sample. Reaction products HD, H2, and D2 were analyzed with a mass spectrometer (GAM200, InProcess Instruments). The mass/charge ratio (m/z) values used are 2 for H2, 4 for D2, and 3 for HD. In situ DRIFTS investigations were performed using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Nicolet 6700) equipped with a mercury cadmium telluride detector. Before measurement, each catalyst was treated with H2 at 300°C for 2 hours and then purged with N2 at 450°C for 2 hours. The catalyst was subsequently cooled down to 280°C. The background spectrum was obtained at 280°C in N2 flow. Then, the sample was exposed to a CO2/H2 mixture (10 ml/min CO2 and 30 ml/min H2) for 90 min. The in situ DRIFT spectra were recorded by collecting 64 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1. IR-MS experiments were performed by combining DRIFTS and MS. The products detected by MS were warmed to be the gas phase. The specific surface area was determined by N2 adsorption using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 system.

DFT calculation

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed with the VASP 5.3.5 package (45). The generalized gradient approximation based on Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional and projected augmented wave method accounting for valence-core interactions were used throughout (46). The kinetic energy cutoff of the plane-wave basis set was set to 400 eV. A Gaussian smearing of the population of partial occupancies with a width of 0.1 eV was used during iterative diagonalization of the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian. The threshold for energy convergence in each iteration was set to 10−5 eV. Convergence was assumed when forces on each atom were less than 0.05 eV/Å in the geometry optimization. The minimum-energy reaction pathways and the corresponding transition states were determined using the nudged elastic band method with improved tangent estimate (CI-NEB) implemented in VASP (47). The maximum energy geometry along the reaction path obtained with the NEB method was further optimized using a quasi-Newton algorithm. In this step, only the adsorbates and the active center of the metal site were relaxed. Frequency analysis of the stationary points was performed by means of the finite difference method as implemented in VASP 5.3.5. Small displacements (0.02 Å) were used to estimate the numerical Hessian matrix. The transition states were confirmed by the presence of a single imaginary frequency corresponding to the specific reaction path.

Both the unit lattice vectors and atoms of hexagonal wurtzite structure ZnO were fully optimized in the first step. The optimized lattice parameters for bulk ZnO are a = b = 3.289 Å and c = 5.312 Å, which are coherent with the experimental values of a = b = 3.249 Å and c = 5.206 Å (48). The Zn-terminated (0001) polar surface slab model of ZnO was constructed by a periodic 4 × 4 × 1 supercell with five Zn-O sublayers and separated by a vacuum layer of 15 Å along the surface normal direction to avoid spurious interactions between the periodic slab models. The top two Zn-O sublayers were fully relaxed, whereas the lowest three layers were fixed at the optimized atomic bulk positions during all the surface calculations. Monkhorst-Pack mesh of 8 × 8 × 6 k-points was used to sample the Brillouin zone for the bulk ZnO, and it was restricted to 2 × 2 × 1 k-points for the supercell surface slab model due to the computational time demands. To eliminate the artificial dipole moment within the slab model of polar ZnO surface, all the oxygen atoms at the bottom of the slab model were saturated by adding pseudo-hydrogen atoms, each containing a positive charge of +0.5 |e|. This strategy effectively removes the internal polarization within the slab, as indicated by the flatter projection of the Hartree potential along the direction of the surface normal compared to other dipole correction methods.

The optimized lattice parameters for tetragonal ZrO2 bulk are a = b = 3.684 Å and c = 5.222 Å, which are in line with the experimental values of a = b = 3.612 Å and c = 5.212 Å (49). The most stable (101) surface of the ZrO2 tetragonal phase was simulated by a 2 × 3 × 1 supercell slab model, including three ZrO2 sublayers (each includes two oxygen atomic layers and one Zr atomic layer), separated by a vacuum layer with a thickness of 15 Å along the surface normal direction to avoid spurious interactions between the periodic slab models. To take into account the effect of Zn2+ doping, one of the Zr4+-O2− moiety on the surface was replaced by a Zn2+ cation and an oxygen vacancy (Zn2+-Ov). The atoms of the top ZrO2 layer were fully optimized, whereas the other two ZrO2 layers at the bottom were fixed at their optimized bulk positions throughout the surface calculations. The on-site Coulomb correction for the Zr 4d states of the ZrO2 bulk and Zn-ZrO2 surface was included by DFT + U approach with a Ueff value of 4.0 eV. K-point grids of 8 × 8 × 6 and 2 × 2 × 1 generated by Monkhorst-Pack scheme were used to sample the Brillouin zones of the ZrO2 bulk and Zn-ZrO2 supercell surface slab model, respectively.

The adsorption energy of the reaction intermediate was calculated as ΔEads = Eadsorbate+surface − Eadsorbate − Eclean−surface. The activation energy (ΔEa) of a chemical reaction was defined as the energy difference between the initial and transition states, whereas the reaction energy (ΔE) was defined as the energy difference between the initial and final states. The enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy of each species were calculated by vibrational frequency analysis based on harmonic normal mode approximation using the finite difference method in VASP. The threshold for energy convergence for each iteration was set to 10−8 eV, and the forces on each atom were 0.01 eV/Å. The Gibbs free energy for a given species is G(T, P) = Ee + Etrans + Erot + Evib + PV-T(Strans + Srot + Svib):where

where I is the moment of inertia, σ is the rotational symmetry number, and m is the mass of the molecule. The translational, rotational, and vibrational enthalpic and entropic contributions of gas-phase molecules were calculated by considering them as ideal gases. For adsorbed molecules and transition states on the surface, the rotational and translational contributions were converted into vibration modes. We also approximated that the PV term of the surface species is negligible because it is very small with regard to the energetic terms, and thus, we considered G(T, P) = Ee + Evib − T × Svib in this case.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Liu and Q. Xin for discussion on FTIR results. Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) Fundamental Research Program for Clean Energy and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB17020200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21621063), and DICP Fundamental Research Program for Clean Energy (DICP M201302). G.L. acknowledges financial support from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) for her personal VENI grant (no. 016.Veni.172.034) and NWO SURFsara for providing access to supercomputer resources. Author contributions: C.L. proposed the project, supervised the research, and wrote and revised the manuscript. J.W. did the experiments and wrote the manuscript. G.L. performed the DFT calculations and drafted part of the manuscript. Z.L. reproduced part of the experiments. C.T. reproduced some catalyst preparation and reaction test. Z.F. and H.A. performed UV Raman spectroscopic characterizations. H.L. and T.L. performed analysis of some experimental and calculation results. All the authors participated in the discussion and agreed with the conclusions of the study. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to support the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/10/e1701290/DC1

table S1. The BET results of catalysts and intrinsic property.

table S2. The catalytic performance of mechanically mixed and supported catalysts.

table S3. DRIFT peak assignments of the surface species for the CO2 + H2(D2) reaction on 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S1. The dependence of methanol selectivity on the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio at a 10% CO2 conversion.

fig. S2. The effect of pressure, H2/CO2 ratio, and GHSV on CO2 hydrogenation.

fig. S3. XRD patterns of ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts.

fig. S4. HRTEM of the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst.

fig. S5. The UV-vis absorbance and Raman spectra of ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S6. XPS of ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S7. H2-TPR of ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S8. XRD of mechanically mixed and supported catalysts.

fig. S9. DRIFT results of CO2 + H2 substituted by CO2 + D2.

fig. S10. Structure of ZrO2 and ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S11. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via formate on the ZnO-ZrO2 (101) surface.

fig. S12. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via CO on the ZnO-ZrO2 (101) surface.

fig. S13. Structure of ZnO.

fig. S14. Hartree potential of the Zn-terminated ZnO (0001) surface calculated by different dipole correction methods.

fig. S15. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates on the ZnO (0001) surface.

fig. S16. Reaction diagram of CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH via formate on the Zn-terminated ZnO (0001) surface.

fig. S17. The catalytic performance contrast of the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 + H2 and CO + H2.

fig. S18. The catalytic performance contrast of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 and ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation.

fig. S19. The stability test of the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.G. A. Olah, A. Goeppert, G. K. Surya Prakash, Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy (Wiley-VCH, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goeppert A., Czaun M., Jones J.-P., Surya Prakash G. K., Olah G. A., Recycling of carbon dioxide to methanol and derived products—Closing the loop. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7995–8048 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porosoff M. D., Yan B., Chen J. G., Catalytic reduction of CO2 by H2 for synthesis of CO, methanol and hydrocarbons: Challenges and opportunities. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 62–73 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centi G., Perathoner S., Opportunities and prospects in the chemical recycling of carbon dioxide to fuels. Catal. Today 148, 191–205 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondratenko E. V., Mul G., Baltrusaitis J., Larrazábal G. O., Pérez-Ramírez J., Status and perspectives of CO2 conversion into fuels and chemicals by catalytic, photocatalytic and electrocatalytic processes. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3112–3135 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrens M., Schlögl R., How to prepare a good Cu/ZnO catalyst or the role of solid state chemistry for the synthesis of nanostructured catalysts. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 639, 2683–2695 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behrens M., Studt F., Kasatkin I., Kühl S., Hävecker M., Abild-Pedersen F., Zander S., Girgsdies F., Kurr P., Kniep B.-L., Tovar M., Fischer R. W., Nørskov J. K., Schlögl R., The active site of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 industrial catalysts. Science 336, 893–897 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan H., Li F., Xin C., Zhao N., Xiao F., Wei W., Sun Y., Performance of the La–Mn–Zn–Cu–O based perovskite precursors for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation. Catal. Lett. 145, 1177–1185 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuld S., Thorhauge M., Falsig H., Elkjær C. F., Helveg S., Chorkendorff I., Sehested J., Quantifying the promotion of Cu catalysts by ZnO for methanol synthesis. Science 352, 969–974 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kattel S., Ramirez P. J., Chen J. G., Rodriguez J. A., Liu P., Active sites for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on Cu/ZnO catalysts. Science 355, 1296–1299 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amenomiya Y., Methanol synthesis from CO2 + H2 II. Copper-based binary and ternary catalysts. Appl. Catal. 30, 57–68 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larmier K., Liao W.-C., Tada S., Lam E., Verel R., Bansode A., Urakawa A., Comas-Vives A., Copéret C., CO2-to-methanol hydrogenation on zirconia-supported copper nanoparticles: Reaction intermediates and the role of the metal–support interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 129, 2358–2363 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kattel S., Yan B., Yang Y., Chen J. G., Liu P., Optimizing binding energies of key intermediates for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over oxide-supported copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12440–12450 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang X.-L., Dong X., Lin G.-D., Zhang H.-B., Carbon nanotube-supported Pd–ZnO catalyst for hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Appl. Catal. B 88, 315–322 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahruji H., Bowker M., Hutchings G., Dimitratos N., Wells P., Gibson E., Jones W., Brookes C., Morgan D., Lalev G., Pd/ZnO catalysts for direct CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. J. Catal. 343, 133–146 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J., Saito M., Takeuchi M., Watanabe T., The stability of Cu/ZnO-based catalysts in methanol synthesis from a CO2-rich feed and from a CO-rich feed. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 218, 235–240 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondrat S. A., Smith P. J., Wells P. P., Chater P. A., Carter J. H., Morgan D. J., Fiordaliso E. M., Wagner J. B., Davies T. E., Lu L., Bartley J. K., Taylor S. H., Spencer M. S., Kiely C. J., Kelly G. J., Park C. W., Rosseinsky M. J., Hutchings G. J., Stable amorphous georgeite as a precursor to a high-activity catalyst. Nature 531, 83–87 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graciani J., Mudiyanselage K., Xu F., Baber A. E., Evans J., Senanayake S. D., Stacchiola D. J., Liu P., Hrbek J., Sanz J. F., Rodriguez J. A., Highly active copper-ceria and copper-ceria-titania catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2. Science 345, 546–550 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Yang X., Kattel S., Senanayake S. D., Boscoboinik J. A., Nie X., Graciani J., Rodriguez J. A., Liu P., Stacchiola D. J., Chen J. G., Low pressure CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over gold nanoparticles activated on a CeOx/TiO2 interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10104–10107 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Studt F., Sharafutdinov I., Abild-Pedersen F., Elkjær C. F., Hummelshøj J. S., Dahl S., Chorkendorff I., Nørskov J. K., Discovery of a Ni-Ga catalyst for carbon dioxide reduction to methanol. Nat. Chem. 6, 320–324 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharafutdinov I., Elkjær C. F., de Carvalho H. W. P., Gardini D., Chiarello G. L., Damsgaard C. D., Wagner J. B., Grunwaldt J.-D., Dahl S., Chorkendorff I., Intermetallic compounds of Ni and Ga as catalysts for the synthesis of methanol. J. Catal. 320, 77–88 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiordaliso E. M., Sharafutdinov I., Carvalho H. W. P., Grunwaldt J.-D., Hansen T. W., Chorkendorff I., Wagner J. B., Damsgaard C. D., Intermetallic GaPd2 nanoparticles on SiO2 for low-pressure CO2 hydrogenation to methanol: Catalytic performance and in situ characterization. ACS Catal. 5, 5827–5836 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye J., Liu C., Mei D., Ge Q., Active oxygen vacancy site for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation on In2O3(110): A DFT study. ACS Catal. 3, 1296–1306 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun K., Fan Z., Ye J., Yan J., Ge Q., Li Y., He W., He W., Yang W., Liu C.-j., Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol over In2O3 catalyst. J. CO2 Util. 12, 1–6 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin O., Martín A. J., Mondelli C., Mitchell S., Segawa T. F., Hauert R., Drouilly C., Curulla-Ferré D., Pérez-Ramírez J., Indium oxide as a superior catalyst for methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 6261–6265 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon R. D., Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A 32, 751–767 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cimino A., Stone F. S., Oxide solid solutions as catalysts. Adv. Catal. 47, 141–306 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H., Kosuda K. M., Van Duyne R. P., Stair P. C., Resonance Raman and surface- and tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy methods to study solid catalysts and heterogeneous catalytic reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4820–4844 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan F., Xu Q., Xia H., Sun K., Feng Z., Li C., UV Raman spectroscopic characterization of catalytic materials. Chin. J. Catal. 30, 717–739 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M., Feng Z., Ying P., Xin Q., Li C., Phase transformation in the surface region of zirconia and doped zirconia detected by UV Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 5, 5326–5332 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi L., Tin K.-C., Wong N.-B., Thermal stability of zirconia membranes. J. Mater. Sci. 34, 3367–3374 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shido T., Iwasawa Y., The effect of coadsorbates in reverse water-gas shift reaction on ZnO, in relation to reactant-promoted reaction mechanism. J. Catal. 140, 575–584 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabatabaei J., Sakakini B. H., Waugh K. C., On the mechanism of methanol synthesis and the water-gas shift reaction on ZnO. Catal. Lett. 110, 77–84 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher I. A., Bell A. T., In-situ infrared study of methanol synthesis from H2/CO2 over Cu/SiO2 and Cu/ZrO2/SiO2. J. Catal. 172, 222–237 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pokrovski K., Jung K. T., Bell A. T., Investigation of CO and CO2 adsorption on tetragonal and monoclinic zirconia. Langmuir 17, 4297–4303 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schild C., Wokaun A., Baiker A., On the mechanism of CO and CO2 hydrogenation reactions on zirconia-supported catalysts: A diffuse reflectance FTIR study: Part II. Surface species on copper/zirconia catalysts: Implications for methanol synthesis selectivity. J. Mol. Catal. 63, 243–254 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goguet A., Meunier F. C., Tibiletti D., Breen J. P., Burch R., Spectrokinetic investigation of reverse water-gas-shift reaction intermediates over a Pt/CeO2 catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 20240–20246 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X., Shi H., Kwak J. H., Szanyi J., Mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation on Pd/Al2O3 catalysts: Kinetics and transient DRIFTS-MS studies. ACS Catal. 5, 6337–6349 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grabow L. C., Mavrikakis M., Mechanism of methanol synthesis on Cu through CO2 and CO hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 1, 365–384 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martínez-Suárez L., Siemer N., Frenzel J., Marx D., Reaction network of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO nanocatalysts. ACS Catal. 5, 4201–4218 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.French S. A., Sokol A. A., Bromley S. T., Catlow R. A., Rogers S. C., King F., Sherwood P., From CO2 to methanol by hybrid QM/MM embedding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 113, 4569–4572 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y.-F., Rousseau R., Li J., Mei D., Theoretical study of syngas hydrogenation to methanol on the polar Zn-terminated ZnO(0001) surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 15952–15961 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaikwad R., Bansode A., Urakawa A., High-pressure advantages in stoichiometric hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol. J. Catal. 343, 127–132 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.An X., Li J., Zuo Y., Zhang Q., Wang D., Wang J., A Cu/Zn/Al/Zr fibrous catalyst that is an improved CO2 hydrogenation to methanol catalyst. Catal. Lett. 118, 264–269 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kresse G., Furthmüller J., Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Wang Y., Generalized gradient approximation for the exchange-correlation hole of a many-electron system. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 54, 16533–16539 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henkelman G., Jónsson H., Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schreyer M., Guo L., Thirunahari S., Gao F., Garland M., Simultaneous determination of several crystal structures from powder mixtures: The combination of powder X-ray diffraction, band-target entropy minimization and Rietveld methods. J. Appl. Cryst. 47, 659–667 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igawa N., Ishii Y., Crystal structure of metastable tetragonal zirconia up to 1473 K. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 84, 1169–1171 (2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/10/e1701290/DC1

table S1. The BET results of catalysts and intrinsic property.

table S2. The catalytic performance of mechanically mixed and supported catalysts.

table S3. DRIFT peak assignments of the surface species for the CO2 + H2(D2) reaction on 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S1. The dependence of methanol selectivity on the Zn/(Zn + Zr) molar ratio at a 10% CO2 conversion.

fig. S2. The effect of pressure, H2/CO2 ratio, and GHSV on CO2 hydrogenation.

fig. S3. XRD patterns of ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts.

fig. S4. HRTEM of the 13% ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst.

fig. S5. The UV-vis absorbance and Raman spectra of ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S6. XPS of ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S7. H2-TPR of ZnO, ZrO2, and 13% ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S8. XRD of mechanically mixed and supported catalysts.

fig. S9. DRIFT results of CO2 + H2 substituted by CO2 + D2.

fig. S10. Structure of ZrO2 and ZnO-ZrO2.

fig. S11. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via formate on the ZnO-ZrO2 (101) surface.

fig. S12. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via CO on the ZnO-ZrO2 (101) surface.

fig. S13. Structure of ZnO.

fig. S14. Hartree potential of the Zn-terminated ZnO (0001) surface calculated by different dipole correction methods.

fig. S15. Local geometries of the reaction intermediates on the ZnO (0001) surface.

fig. S16. Reaction diagram of CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH via formate on the Zn-terminated ZnO (0001) surface.

fig. S17. The catalytic performance contrast of the ZnO-ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 + H2 and CO + H2.

fig. S18. The catalytic performance contrast of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 and ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation.

fig. S19. The stability test of the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst.