Abstract

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), two nuclei within the central extended amygdala, function as critical relays within the distributed neural networks that coordinate sensory, emotional, and cognitive responses to threat. These structures have overlapping anatomical projections to downstream targets that initiate defensive responses. Despite these commonalities, researchers have also proposed a functional dissociation between the CeA and BNST, with the CeA promoting responses to discrete stimuli and the BNST promoting responses to diffuse threat. Intrinsic functional connectivity (iFC) provides a means to investigate the functional architecture of the brain, unbiased by task demands. Using ultra-high field neuroimaging (7-Tesla fMRI), which provides increased spatial resolution, this study compared the iFC networks of the CeA and BNST in 27 healthy individuals. Both structures were coupled with areas of the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and periaqueductal gray matter. Compared to the BNST, the bilateral CeA was more strongly coupled with the insula and regions that support sensory processing, including thalamus and fusiform gyrus. In contrast, the bilateral BNST was more strongly coupled with regions involved in cognitive and motivational processes, including the dorsal paracingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and striatum. Collectively, these findings suggest that responses to sensory stimulation are preferentially coordinated by the CeA and cognitive and motivational responses are preferentially coordinated by the BNST.

Keywords: Central nucleus of the amygdale, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis BNST, resting state networks, intrinsic functional connectivity, 7-Tesla fMRI

1. Introduction

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and the lateral bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST) are two small, highly interconnected structures, which are the key components of the central extended amygdala (Olmos & Heimer, 1999). Anatomical tracing studies in animals demonstrate that the CeA and BNST are both ideally positioned to contribute to the behavioral and physiological responses to threat (Davis & Shi, 1999) and a large animal literature suggests that these structures function to maintain defensive responses to threat in the environment (Davis, Walker, Miles, & Grillon, 2010). Researchers have suggested that the central extended amygdala plays a critical role in the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse (Avery, Clauss, & Blackford, 2016; Koob & Volkow, 2010; Shin & Liberzon, 2009) which highlights the importance of developing a deeper understanding of the functional role played by the CeA and BNST. Previously, we reported on the intrinsic connectivity of the BNST using ultra-high field neuroimaging (7-Tesla fMRI), which provides increased spatial resolution and provides an opportunity to examine the functional architecture of small neural structures (Torrisi et al., 2015). Here, we set out to address the novel question of whether patterns of functional connections differentiate the BNST from the CeA, within these same participants.

In addition to their shared efferent projections to effector centers for defensive responses, such as the PAG, the CeA and BNST both receive afferents from structures of the emotion processing network such as the hippocampus, insula, and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Bienkowski & Rinaman, 2012; Cullinan, Herman, & Watson, 1993; Hurley, Herbert, Moga, & Saper, 1991; Shi & Cassell, 1998). Despite widespread commonalities in CeA and BNST patterns of anatomical connectivity, notable differences exist. Recent research in rodents has demonstrated that the CeA receives a higher number of projections from cortical and sensory-related regions relative to the BNST, whereas the BNST showed preferential inputs from areas of the striatum (Bienkowski & Rinaman, 2012). Additionally, lesions of the CeA block the expression of threat-related responses to conditioned cues during aversive Pavlovian conditioning, whereas lesions of the BNST block threat-related responses more diffuse aversive contextual stimuli (Sullivan et al., 2004; Waddell, Morris, & Bouton, 2006). This behavioral dissociation has led researchers to suggest that the CeA is preferentially involved in “fear” responses to imminent threat, whereas the BNST orchestrates “anxiety-like” responses to more diffuse and uncertain threat (Davis et al., 2010). However, this specialization has recently been questioned, based on observations that the CeA and BNST both respond to discrete, as well as diffuse, threat (Shackman & Fox, 2016). An important way to contribute to this debate is to compare the functional networks associated with these two structures.

iFC reflects the coherence of low frequency activity among brain regions, and provides maps of brain functional networks (Fox & Raichle, 2007) which can shed light on the potential similarities and differences between these two nuclei. Critically, previous research has demonstrated that patterns of iFC can characterize functional heterogeneity within neural structures (Cohen et al., 2008; Deen, Pitskel, & Pelphrey, 2011; Shen, Papademetris, & Constable, 2010), including the amygdala (Roy et al., 2009). Yet to date, no research has directly examined the functional heterogeneity within the dorsal extended amygdala (i.e., the BNST and CeA) using measures of iFC.

Although resting-state functional connectivity partly reflects the strength of anatomical projections (Deco, Jirsa, & McIntosh, 2011), it is not limited to monosynaptic connections and can also reveal more distributed networks of regions working together (Raichle, 2009). Importantly, neural structures that lack direct anatomical projections to the CeA and BNST, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or posterior cingulate, are involved with the cognitive processing of negative information (Berman et al., 2010; Cooney, Joormann, Eugène, Dennis, & Gotlib, 2010), and may be highly relevant to subjective feelings of fear and anxiety. Comparing the iFC networks of the CeA and BNST can clarify whether and how these structures interact with higher-order cognitive systems.

Previous research has demonstrated that the central/medial region of the amygdala, including the CeA, is functionally connected to multiple nodes of the emotional processing network, such as the hippocampus, mPFC, anterior insula, and striatum (Roy et al., 2009). Studies that have assessed the iFC networks of the CeA specifically, demonstrate functional connections to regions that support cued aversive Pavlovian conditioning (i.e. the dorsal anterior cingulate and thalamus) and sensory processing (i.e. occipital cortex, temporal area TE, and the superior temporal sulcus) (Birn et al., 2014; Oler et al., 2012, 2016). Although previous research suggests that the BNST is functionally connected to the mPFC, hippocampus, thalamus, and striatum (Avery et al., 2014; Torrisi et al., 2015), these studies do not report functional connections with the anterior insula. This raises the possibility that the CeA and BNST differ in their functional connections throughout the brain. However, direct comparisons of the iFC networks of the CeA and BNST cannot be based on previous literature due to variability in the sample, data collection, and analysis methods used to determine iFC. Here, we set out to address this gap in the literature by using ultra-high field neuroimaging (7-Tesla fMRI) to directly contrast the relative iFC strength of the BNST, which has previously been reported for this sample (Torrisi et al., 2015), to the relative iFC strength of the CeA.

Based on the known anatomical projections and previously reported iFC networks of these structures, we predicted that both the CeA and BNST would exhibit strong iFC patterns with the PAG, thalamus, and hypothalamus, all of which receive afferents from both the CeA and BNST. Furthermore, we predicted that the CeA would exhibit significantly stronger iFC with the neural structures that support fear-related processes (e.g., cued aversive Pavlovian learning) and that the BNST would exhibit significantly stronger iFC with the neural structures that support anxiety-related processes (e.g., contextual aversive conditioning). Accordingly, the CeA would be expected to be coupled more strongly with the dACC, anterior insula, thalamus, and areas of sensory cortex (Fullana et al., 2016), whereas the BNST would be more strongly coupled with the anterior hippocampus (Avery et al., 2014; Maren, Phan, & Liberzon, 2013; Strange, Witter, Lein, & Moser, 2014; Torrisi et al., 2015), and regions associated with cognitive processes (e.g., worry) recruited in response to anxiety (mPFC and medial posterior cingulate cortex (Cooney et al., 2010; Paulesu et al., 2010). Third, based on a recent tract-tracing report (Bienkowski & Rinaman, 2012), the BNST would be relatively more strongly coupled with the striatum, whereas the CeA would be relatively more strongly coupled with somatosensory information processing regions.

Finally, iFC patterns of the amygdala have been shown to be functionally lateralized (Makovac et al., 2016; Roy et al., 2009). Previous research suggests that the left amygdala habituates more slowly than the right, which has led researchers to suggest that the left amygdala is specialized for sustained attention to discrete stimuli, whereas the right amygdala is specialized for the dynamic detection of emotional cues (Wright et al., 2001). Regarding the BNST, lesions to the medial frontal lobe impact the metabolism of the right, but not left BNST (Motzkin et al., 2015). Taken together, these reports suggest that both the CeA and BNST may exhibit different laterality effects across left and right hemispheres. Although we make no a priori hypotheses concerning the location or directionality of these effects, we expect that our exploratory analyses might reveal similar hemispheric asymmetries when comparing the CeA to the BNST, as those reported regarding iFC patterns of the amygdala (Makovac et al., 2016; Roy et al., 2009).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample reported here is identical to that reported in Torrisi et al., 2015. Twenty-nine right-handed volunteers were recruited via flyers, print advertisements, and internet listservs for participation in this study. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants and approved by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board. All participants were free from the following exclusionary criteria: (a) current or past Axis I psychiatric disorder as assessed through a clinician administered SCID-I/NP (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001), (b) first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder, (c) a medical condition conflicting with safety or design of the study, (d) brain abnormality on MRI as assessed by a radiologist, (e) positive toxicology screen, or (f) MRI contraindication. Two participants were omitted from analyses due to excessive head motion (i.e., more than 15% of acquired TRs with a frame-to-frame Euclidean norm motion derivative greater than 0.3 mm) leaving a final sample of 27 participants (M = 27.3 ± 6 SD years; 14 women).

2.2. Physiological Measures

To correct the fMRI data for nuisance physiological signals, respiration was measured using a pneumatic belt placed around the diaphragm, and cardiac rhythm was measured using a pulse oximeter affixed to the right index finger. Such correction has been shown to greatly improve temporal signal-to-noise and BOLD sensitivity at high spatial resolution (Hutton et al., 2011). Physiological data were sampled at 500 Hz using a BioPac MP150 system (www.biopac.com).

2.3. BOLD fMRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens Magnetom 7T scanner and 32-chanel head coil. Third-order shimming was used to correct for field inhomogeneities. Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal was acquired using T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) across 49 ascending interleaved axial slices using the following parameters: TR = 2,500 ms, TE = 27 ms, flip angle = 70°, 1.3 mm3 voxels, acquisition matrix = 154 × 154; 240 volumes (10 min). A partial-brain field-of-view (FOV) was selected to capture dorsal ACC/mPFC, BNST, amygdala, and hippocampus, while avoiding the eyes, which can contribute to artifact (see Supplementary Figure 1 for illustration of brain coverage). During the scan, participants were instructed to remain awake and fixate on a white cross presented on a black background. All participants reported keeping their eyes open during the resting-state scan. A 0.7 mm isotropic T1-weighted anatomical image was also collected using a gradient-echo sequence (TR = 2,200 ms, TE = 3.01, flip angle 7°, acquisition matrix = 320 × 320).

2.4. CeA and BNST Seed ROIs

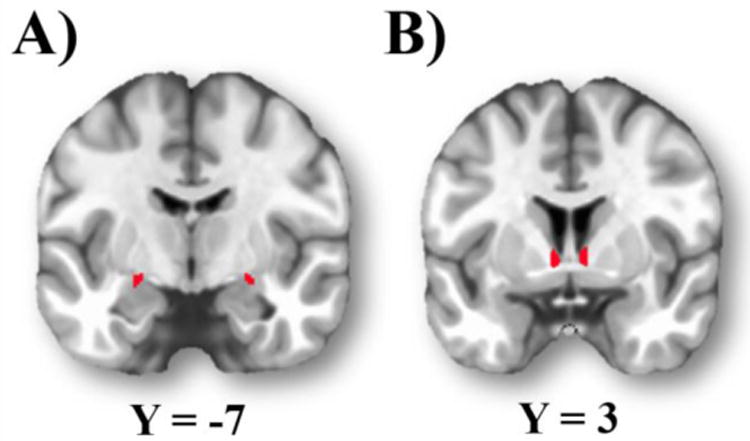

As shown in Figure 1A, the left and right CeA seed regions of interest (ROIs) were defined using the publicly available probabilistic atlas of Tyska and Pauli (Tyszka & Pauli, 2016), and thresholded at 20%.

Figure 1.

Seed ROIs for intrinsic connectivity analyses. A): central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA); B): bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST).

Left and right BNST seed ROIs (Figure 1B) were manually prescribed on each participants' T1-weighted image in native space as described previously (Torrisi et al., 2015). Briefly, three authors independently demarcated the boundaries of the BNST for each participant based on anatomical criteria. The three binary masks were averaged and final ROIs were determined by majority consensus (i.e., thresholded at .667).

The volume of CeA seeds (left = 58 voxels; right = 46 voxels) and BNST seeds was similar (left = 35.41 ± 9.7 voxels; right = 38.44 ± 8.4 voxels). However, follow-up analyses demonstrate that our results are largely unchanged when the CeA seed is thresholded to best reflect a priori neuroanatomical estimates of volume (for details, see Supplemental Materials).

2.5. BOLD fMRI Data Preprocessing and Analysis

Resting state preprocessing began with FreeSurfer tissue segmentation (Fischl et al., 2002). Ventricular images were resampled to 1.0 mm isotropic voxel resolution and eroded by one voxel in each direction to ensure that these areas did not overlap with gray or white matter. The rest of preprocessing and analyses then continued using AFNI (Cox, 1996). The first three volumes of the functional run were discarded to allow for steady-state equilibrium. Functional volumes were slice-time corrected using 3dTshift, motion corrected and realigned using 3dvolreg, and co-registered to corresponding T1-weighted image using 3dAllineate. T1-weighted images were normalized using 3dQwarp to the “ICBM 2009b Nonlinear Asymmetric” template in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space (http://www.bic.mni.mcgill.ca/ServicesAtlases/ICBM152NLin2009) (Fonov et al., 2011; Fonov, Evans, McKinstry, Almli, & Collins, 2009). The resulting affine plus nonlinear parameters were then applied to the functional volumes, which were then spatially smoothed (2.6-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel). The final nominal resolution of our functional data remained at 1.3 mm3.

The following nuisance signals were regressed from the functional volumes: 1) six head motion parameters and their first derivatives; 2) eight slice-based cardiac regressors (Glover, Li, & Ress, 2000); 3) five slice-based respiration regressors (Birn, Smith, Jones, & Bandettini, 2008; Glover et al., 2000); 4) time series extracted from the lateral, 3rd, and 4th ventricles; 5) 0.01–0.1 Hz bandpass filter regressors; and 6) time-series from local white matter within a 13-mm radius sphere surrounding each voxel using the ANATICOR approach (Jo, Saad, Simmons, Milbury, & Cox, 2010). Average time series were extracted for both bilateral seed ROIs, and separate seeds for each hemisphere from the residualized functional images within the CeA and BNST. Pearson correlations between each time series and all other voxels in the brain were calculated and Fisher r-to-z transformed for group analyses.

2.6. Statistics and Analytic Strategy

The Fisher-transformed statistical images resulting from our preprocessing stream represent estimates of iFC. Statistical images reflecting the iFC of the bilateral CeA and of the bilateral BNST were entered into separate one-sample t-tests to determine which voxels exhibited iFC that was significantly different from zero.

Paired t-tests were used to contrast CeA-iFC to BNST-iFC. The variable used was the Fisher-transformed statistical variable reflecting the iFC of the bilateral CeA and bilateral BNST.

Differences between CeA and BNST iFC can be driven by two patterns: 1) the iFC for one seed is significantly greater than zero, whereas the iFC for the second seed is not significantly different from zero, leading to significant greater iFC for the first seed compared to the second; and 2) the iFC is significantly greater than zero for both seeds, yet the mean iFC for one seed is nonetheless significantly greater than the other. In order to distinguish between these two patterns, clusters identified as exhibiting different iFC between CeA and BNST were characterized as being located within areas that exhibited iFC with each seed, or areas in which the iFC for the two seeds overlapped.

Following the identification of the voxels which exhibited significant iFC with the CeA and BNST respectively, results from each one sample t-test were binarized, such that all voxels that survived correction for multiple comparisons were assigned a value of 1, whereas all other voxels were assigned a value of zero. The resulting binarized images were then multiplied together to reveal the conjunction of CeA and BNST iFC patterns. Here, the term conjunction refers to the logical operator “AND” (Nichols, Brett, Andersson, Wager, & Poline, 2005). Specifically, the logical conjunction of A and B is true, when both A is true and B is true.

Finally, an exploratory analysis was conducted to assess hemispheric differences of iFC between CeA and BNST. Statistical time-series for the left and right CeA, and for left and right BNST were entered into a repeated-measures ANOVA model to test for interactions of seeds (CeA vs. BNST) with hemisphere (left vs. right).

All group-level statistical maps were thresholded (p<0.05, whole-brain corrected) based on cluster extent, using a cluster-forming threshold of (p < 0.0005, k = 21 (p = 5 × 10̂−4)) via updated versions of 3dFWHMx and 3dClustSim. These updates incorporate a mixed autocorrelation function (acf) that better models non-Gaussian noise structure (Cox, Reynolds, & Taylor, 2016; Eklund, Nichols, & Knutsson, 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Bilateral CeA and BNST iFC

The CeA showed significant iFC with cortical and subcortical regions, including distributed regions of the cortex, medial temporal lobes, BNST, striatum, PAG, and cerebellum (Supplemental Figure 2).

The BNST iFC has been previously reported for these participants (Torrisi et al., 2015). In brief, the BNST was intrinsically coupled with cortical and subcortical regions, notably the CeA, striatum, PAG, and cerebellum (Supplemental Figure 3).

No negative associations (i.e. anti-correlations) were detected at corrected thresholds for either the CeA or BNST seed.

3.2. Target regions shared by bilateral CeA and BNST iFC

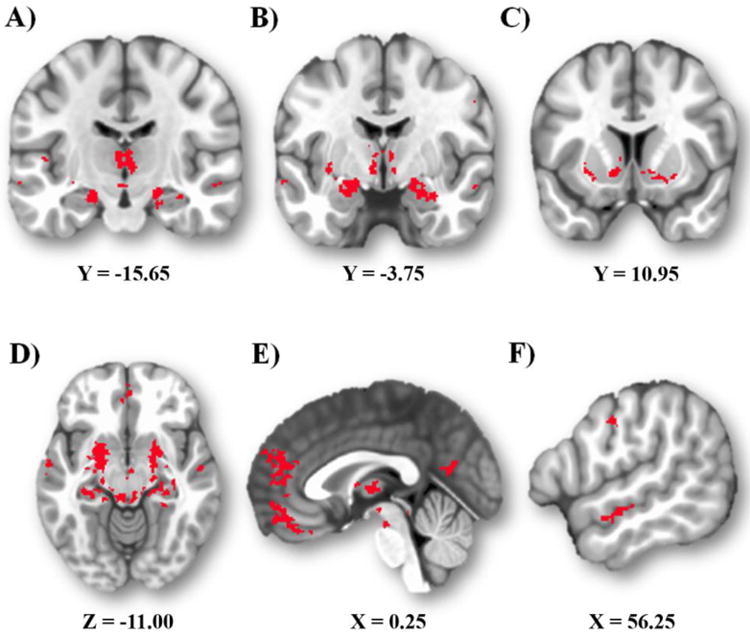

As expected, a number of regions exhibited significant iFC with both the CeA and BNST (Figure 2 and Table 1) as indexed by a conjunction analysis. These shared target regions were distributed across subcortical and cortical areas. Subcortically, they included midline thalamus (including areas consistent with the nucleus reuniens and medial dorsal thalamus), anterior and posterior hippocampus (Figure 2A), amygdala (including areas consistent with the lateral and basal amygdala nuclei) (Figure 2B), striatal regions (caudate, ventral striatum, putamen) (Figure 2C), and multiple areas of the midbrain, notably PAG (Figure 2D). Cortically, they consisted of clusters in the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. Frontal cortical regions included an mPFC cluster, extending ventrally into orbitofrontal cortex (BA11) and dorsally into dorsal mPFC (BA9/10), and a rostral mPFC cluster within the paracingulate gyrus (Figure 2E). Parietal cortical regions were in the precuneus (Figure 2E). The temporal cortical cluster was within the superior temporal sulcus (Figure 2F). Finally, the posterior insula was also coupled with both CeA and BNST.

Figure 2.

Shared coupling. Regions showing significant iFC with both the CeA and BNST are depicted in red (p<.05, whole-brain corrected). A) Thalamus and hippocampus. B) Amygdala, including regions of the lateral and basal nuclei. C) Striatum, including the caudate, putamen, and ventral striatum. D) Midbrain, including the PAG. E) mPFC. F) Superior temporal sulcus.

Table 1.

Spatial coordinates from the center of mass of clusters exhibiting intrinsic connectivity with both the CeA and BNST as determined by the overlap between one-sample t-tests.

| Coordinates | # of voxels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcortical | X | Y | Z | ||

| Right medial temporal lobe | 20.7 | -9.8 | -11.3 | 1660 | |

| -contiguous cluster including the hippocampus, amygdala, basal forebrain, striatum, and thalamus | |||||

| Left medial temporal lobe | -15.8 | -8.4 | -7.1 | 2353 | |

| - contiguous cluster including the hippocampus, amygdala, basal forebrain, striatum, and thalamus | |||||

| Right caudate (body) | 10.4 | 3.6 | 13.1 | 32 | |

| 8.2 | 15.7 | 6.7 | 21 | ||

| Left insula | -38.7 | -22.4 | 4 | 46 | |

| Right parahippocampal gyrus | 28.7 | -35.6 | -13.8 | 54 | |

| 24 | -29.8 | -18.3 | 40 | ||

| Left parahippocampal gyrus | -29.2 | -42.6 | -7.1 | 30 | |

| -22.6 | -38.8 | -15.9 | 25 | ||

| -17.7 | -33.3 | -11.7 | 21 | ||

| Right thalamus | 11.7 | -25 | -10.1 | 31 | |

| 3.2 | -10.9 | -10.4 | 30 | ||

| Left thalamus | -13.9 | -26.7 | -7 | 76 | |

| -1.6 | -15.1 | -9.8 | 29 | ||

| Left claustrum | -33.2 | -4 | -4.4 | 26 | |

| PAG | 0.3 | -31.8 | -11.3 | 187 | |

| Midbrain | -0.2 | -21 | -19.7 | 29 | |

| Frontal Lobe | |||||

| mPFC | -1.5 | 49.4 | 5.9 | 1312 | |

| -1.4 | 30 | -23.2 | 23 | ||

| Right inferior frontal gyrus | 28.6 | 15.8 | -18.9 | 59 | |

| Left inferior frontal gyrus | -30.6 | 15.2 | -18.2 | 25 | |

| Right precentral Gyrus | 55.7 | -6.6 | 37.8 | 25 | |

| Left precentral Gyrus | -58.2 | -10.3 | 36.7 | 37 | |

| Right middle Frontal Gyrus | 38.4 | 35.6 | -15.5 | 34 | |

| Temporal Lobe | |||||

| Right superior temporal sulcus | 55.9 | -10.4 | -11 | 114 | |

| Left superior temporal sulcus | -61.9 | -7.5 | -9.3 | 128 | |

| -64.2 | -20.7 | -8.3 | 40 | ||

| Left superior temporal gyrus | -60.7 | 7.3 | -5.6 | 31 | |

| -49.8 | -13.2 | 6.8 | 26 | ||

| -67.1 | -44.4 | 16.8 | 23 | ||

| Left transverse temporal gyrus | -50.3 | -24 | 12.4 | 48 | |

| -41.9 | -32.2 | 11.4 | 37 | ||

| Right transverse temporal gyrus | 46.6 | -20.6 | 10.1 | 22 | |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus (BA39) | -51.1 | -68.1 | 9.7 | 46 | |

| Left Fusiform Gyrus | -46.6 | -57.1 | -21.5 | 29 | |

| Parietal Lobe | Precuneus | 3.2 | -59.7 | 18 | 359 |

| Posterior Cingulate | -15.7 | -54 | 4.7 | 33 | |

| 6.7 | -59.6 | 27.6 | 28 | ||

| -3.8 | -57.3 | 19.9 | 23 | ||

| Occipital Lobe | Left middle Occipital Gyrus | -50.6 | -78.9 | -2.2 | 77 |

| Cerebellum | Right culmen | 15.1 | -54.9 | -15.2 | 107 |

3.3. Target regions that differ between bilateral CeA and BNST iFC

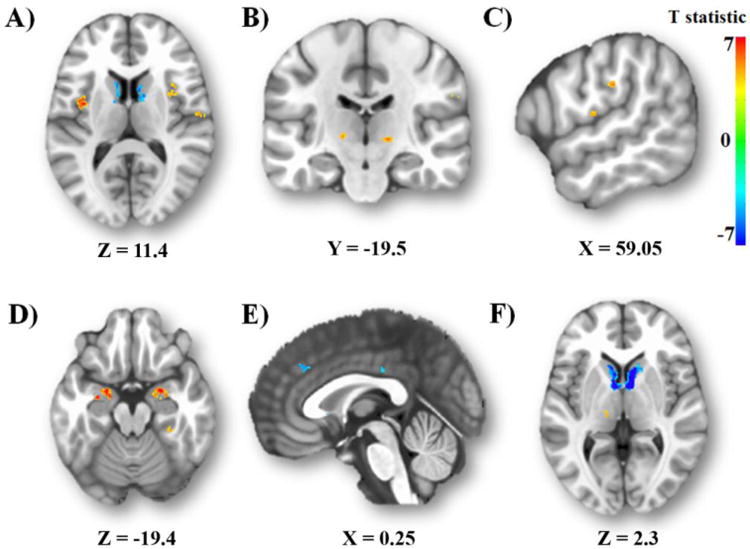

3.3.1. Regions more strongly connected to CeA

As shown in Figure 3, a paired t-test revealed significant differences in regional iFC between the CeA and BNST (Table 2). Compared to the BNST, the CeA was more strongly coupled with the middle insula (Figure 3A), ventral posterior thalamus (Figure 3B), supramarginal gyrus (BA40) (Figure 3C), post-central gyrus (BA43) (Figure 3C), fusiform cortex (Figure 3D) and areas of the amygdala. These amygdala regions included areas which were consistent with the basal and lateral nuclei.

Figure 3.

Distinct connections. Regions with greater CeA iFC are depicted in red-yellow, whereas regions with greater BNST iFC are depicted in blue (p<.05, whole-brain corrected). CeA-preferring regions include the (A) middle insula, (B) ventral posterior thalamus, (C) postcentral and supramarginal gyri, and (D) and fusiform gyrus. BNST-preferring regions include the (E) paracingulate gyrus and posterior cingulate and (F) head and body of the caudate nucleus bilaterally, extending into ventral striatum.

Table 2.

Spatial coordinates and statistics from peak voxels exhibiting significantly different intrinsic connectivity (CeA vs. BNST) as determined by paired t-tests

| Coordinates | T statistic | # of voxels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| BNST > CeA | X | Y | Z | |||

| Right BNST, caudate | 6.8 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 18.33 | 1123 | |

| Left BNST, caudate | -7.6 | 4.3 | -1.2 | 20.87 | 963 | |

| Paracingulate gyrus | -3.7 | 34.2 | 33.9 | 5.83 | 74 | |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | 4.1 | -26.8 | 31.3 | 5.4 | 33 | |

| CeA > BNST | ||||||

| Right amygdala | 26.2 | -10 | -11.5 | 16.54 | 756 | |

| Left amygdala | -24.5 | -10 | -11.5 | 21.16 | 691 | |

| Left insula | -41.4 | -2.2 | 9.2 | 7.74 | 188 | |

| -40.1 | 0.4 | -9 | 5.66 | 60 | ||

| Right insula | 36.6 | 0.4 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 127 | |

| 43.1 | 9.6 | -7.7 | 7.09 | 23 | ||

| 36.6 | 4.3 | -12.9 | 4.91 | 21 | ||

| Right thalamus | 15.8 | -17.8 | -1.2 | 5.89 | 47 | |

| Left thalamus | -15.4 | -19.1 | 1.4 | 5.16 | 26 | |

| Post-central gyrus | 58.8 | -21.7 | 28.8 | 5.29 | 37 | |

| Right supramarginal gyrus | 62.6 | -13.8 | 14.4 | 5.68 | 32 | |

| Right fusiform gyrus | 32.8 | -35.9 | -18 | 5.4 | 26 | |

To fully characterize differences between CeA and BNST iFCs, the location of each significant cluster was carefully assessed in relation to the map of shared iFC (conjunction analysis). The cluster located within the post-central gyrus did not overlap with either the conjunction analysis or the areas identified as exhibiting iFC with CeA via one-sample t-test. All clusters not centered on the right or left amygdala, including all clusters in the insula, thalamus, supramarginal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus (Table 2) existed outside of the areas identified through the conjunction analysis. The majority of the voxels in these clusters overlapped with areas identified as exhibiting iFC with CeA via one-sample t-test (average cluster overlap = 86.8% of voxels, range = 68.8 – 100%). Meanwhile, of the voxels centered on the amygdala which were more strongly coupled with the CeA, approximately 30 percent were located within the conjunction analysis (left: 203 voxels, right: 222 voxels) and mostly centered within the dorsal amygdala. The remaining voxels within the amygdala which were more strongly coupled with the CeA existed outside of the conjunction mask (left: 488 voxels, right: 534 voxels) and centered mostly within the ventral and lateral aspects of the amygdala.

3.3.2. Regions more strongly connected to BNST

Compared to the CeA, the BNST was more strongly coupled with the paracingulate gyrus (on the border of BA9/32) and posterior cingulate cortex (BA23) (Figure 3E). The BNST was also more strongly coupled with a cluster in the head and body of the caudate nucleus bilaterally, extending into the ventral striatum (Figure 3F).

Notably, the clusters located within the paracingulate gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex did not fall within the conjunction mask. The voxels within these clusters partially overlapped with areas identified as exhibiting iFC with BNST via one-sample t-test for both the paracingulate gyrus (63.5%) and the posterior cingulate cortex (36.4%). Meanwhile, approximately 12 percent of the voxels within the contiguous clusters centered on the BNST fall within the conjunction mask (left: 103 voxels, right: 135 voxels) centered on the BNST and ventral striatum, whereas the remaining voxels in the cluster (left: 860 voxels, right: 988 voxels) fall outside of the conjunction analysis within the dorsal striatum and caudate.

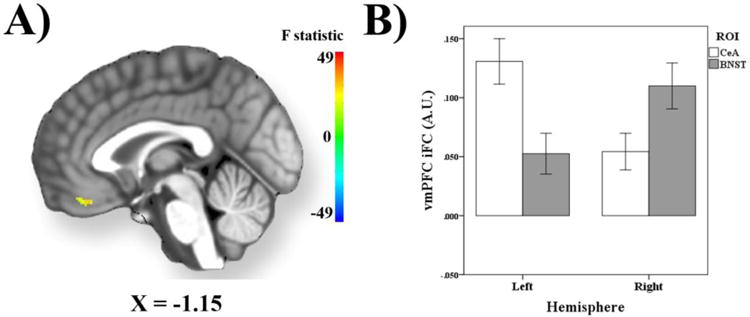

3.4. Effects of Hemisphere

Critically, repeated measure ANOVA analyses revealed interactions between seed and hemisphere, such that differences in the iFC patterns between the CeA and BNST were significantly different in the left and right hemispheres (Table 3). Four clusters which exhibited an interaction between seed and hemisphere were centered on the right and left CeA and BNST. Additional clusters exhibiting interactions were detected within the middle temporal gyrus (BA 38), the inferior frontal gyrus (BA 44), and vmPFC (BA 11). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that these three clusters were driven by a similar pattern of results with the CeA exhibiting significantly stronger iFC compared to the BNST in the left hemisphere (middle temporal gyrus: T = 4.33, p < 0.001; inferior gyrus: T = 3.00, p < 0.01; vmPFC: T = 3.53, p < 0.005), whereas the BNST exhibited significantly stronger iFC compared to the CeA in the right hemisphere (middle temporal gyrus: T = -3.50, p < 0.005; inferior gyrus: T = -2.78, p < 0.05; vmPFC: T = -2.25, p < 0.05). Further, iFC of the left CeA was significantly stronger than the connectivity of the right CeA (middle temporal gyrus: T = 5.00, p < 0.001; inferior gyrus: T = 4.71, p < 0.001; vmPFC: T = 4.81, p < 0.001), whereas for the BNST the right hemisphere consistently demonstrated enhanced connectivity (middle temporal gyrus: T = -3.71, p < 0.001; inferior gyrus: T = -2.34, p < 0.05; vmPFC: T = -3.63, p < 0.001). No post-hoc comparisons between left CeA and right BNST, or between right CeA and left BNST reached statistical significance (all p's > 0.05).

Table 3.

Spatial coordinates and statistics from peak voxels exhibiting a significant seed ROI (CeA vs. BNST) × Hemisphere (left vs. right) interaction as determined by repeated measure ANOVA.

| Coordinates | F statistic | # of voxels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed ROI × Hemisphere | ||||||

| Right BNST | 6.8 | 5.6 | -1.2 | 225.31 | 204 | |

| Left CeA | -23.2 | -8.7 | -11.5 | 327.00 | 181 | |

| Right CeA | 26.2 | -8.7 | -11.5 | 327.00 | 149 | |

| Left BNST | -6.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 174.42 | 102 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | -54.4 | 22.6 | 23.5 | 39.92 | 35 | |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | -1.1 | 35.6 | -23.2 | 30.46 | 31 | |

| Middle temporal gyrus | -57.0 | 5.6 | -22.0 | 27.43 | 21 | |

Notably, the vmPFC (Figure 4) cluster exhibiting an interaction between seed ROI and hemisphere was located within the conjunction mask and was also located within an area that demonstrated an effect of hemisphere, specifically left CeA > right CeA, after correction for multiple comparisons (for details see, Supplemental Tables).

Figure 4.

Seed ROI x Hemisphere Effects within Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex. (A) Statistical image depicting results within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) that exhibit a significant interaction between seed ROI (CeA vs. BNST) and hemisphere (left vs. right). (B) Bar graphs depicting mean iFC values from the vmPFC as a function of ROI and hemisphere. iFC values are reported in arbitrary units (A.U.). Error bars reflect 1 standard error.

For completeness, we report results from paired t-tests assessing differences between left and right hemispheres, for both CeA and BNST seeds separately, within Supplemental Materials (for details, see Supplemental Table 2 and 3).

4. Discussion

In line with expectations, the whole-brain iFC maps of the CeA and BNST exhibited broad overlaps, particularly regarding connectivity with downstream neural effectors for defensive responses, such as the PAG and areas of the midbrain, and with upstream structures involved in threat-related information processing, such as the mPFC, hippocampus, and thalamus. The main and novel findings concern the regional differences in whole-brain iFC of these two structures. The CeA was more strongly connected to the insula, a region involved in internal-state information processing (Craig, 2002), and to regions supporting sensory processing, i.e., thalamus and fusiform gyrus (Alitto & Usrey, 2003; Tyler et al., 2013). Conversely, the BNST was more strongly connected to regions involved in the conscious appraisal of threat and decision-making, i.e., dorsal paracingulate gyrus (Mechias, Etkin, & Kalisch, 2010; Venkatraman, Rosati, Taren, & Huettel, 2009), motivated behavior, i.e., striatum (Liljeholm & O'Doherty, 2012), and self-referential processes, i.e., posterior cingulate cortex (pCC) (Northoff et al., 2006). Additionally, our results further demonstrate that the relative iFC strength of the CeA compared to the BNST within the vmPFC, inferior frontal gyrus, and middle temporal gyrus, vary between left and right hemispheres of the brain. These differences in iFC between the CeA and BNST will be discussed within the framework of the ongoing debate about the relative role of these structures in defensive responses (e.g. Davis et al., 2010; Shackman & Fox, 2016).

4.1. CeA, BNST, and defensive responses to threat

In agreement with findings from anatomical studies, both the CeA and the BNST were intrinsically connected to the PAG and areas of the midbrain. The PAG mediates physiological and behavioral defensive responses (Bandler, Keay, Floyd, & Price, 2000; LeDoux, Iwata, Cicchetti, & Reis, 1988) and the overlapping intrinsic connectivity of the CeA and the BNST with this structure may reflect their common role in initiating defensive responses to environmental threat.

Additionally, both the CeA and BNST exhibited intrinsic connectivity with multiple areas of the midline thalamus which previous research has suggested are important for the processing of threatening information. Both the CeA and BNST were intrinsically connected to an area of the thalamus consistent with the interthalamic adhesion. The interthalamic adhesion contains the nucleus reuniens, which is known from non-human research to receive afferents from both the CeA and BNST (Aggleton & Mishkin, 1984; Dong & Swanson, 2004). Additionally, areas of the medial dorsal thalamus likewise exhibit functional connections with both the CeA and BNST. Stimulation of the medial dorsal thalamus results in defensive behavioral responses (Roberts, 1962), and previous research suggests that the medial dorsal thalamus is involved with cued and context conditioning (Antoniadis & McDonald, 2006; Sarter & Markowitsch, 1985). Although our observed results do not extend into the lateral geniculate nucleus, the anatomical specificity of our findings suggests that patterns of iFC likely reflect the functional role of these thalamic nuclei in processing threatening emotional information.

Lastly, the CeA and BNST were both intrinsically connected to the caudate and regions of the ventral striatum, hippocampus, and large regions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Specifically, areas of the medial prefrontal cortex included regions of vmPFC (BA 11) and more dorsal areas of the medial frontal lobe (BA 9/10), but few clusters were observed more caudally (i.e. BA 8/32). Exposure to threat can impact operant responding (Jaisinghani & Rosenkranz, 2015), in addition to influencing sensory (Grosso, Cambiaghi, Concina, Sacco, & Sacchetti, 2015) and cognitive processes (Okon-Singer, Hendler, Pessoa, & Shackman, 2015). The present results suggest that the CeA and BNST both interact with the neural networks that support instrumental, sensory, and cognitive responses to threat.

4.2. CeA: preferential coupling with somatic and sensory networks

The CeA, relative to the BNST, exhibited stronger coupling with targets involved in sensory processing. These regions consisted of the ventral posterior thalamus, the mid-insula, the fusiform gyrus, and areas of the post-central gyrus.

The thalamus is a complex multi-nuclei structure, and the ventral-posterior region of the thalamus processes noxious somatosensory information (Casey & Morrow, 1983). Fibers from the ventral-posterior thalamic region also co-terminate in the amygdala together with with input from other perceptual systems (Paré, Quirk, & Ledoux, 2004). The co-occurrence of action potentials from neurons responding to noxious stimuli and other neurons responding to perceptual qualities of originally neutral stimuli may form the basis of aversive stimulus-stimulus associations (Blair, Schafe, Bauer, Rodrigues, & LeDoux, 2001), and the greater iFC between the CeA and the ventral-posterior thalamic region may reflect the role of this thalamic subregion in facilitating fear conditioning.

The insula is a primary hub for processing interoceptive information (Craig, 2002). The iFC networks of the insula can be divided into three functional subdivisions (Deen et al., 2011). The dorsal anterior insula is functionally connected to the dACC and cognitive control network, the ventral anterior insula is connected to the pregenual cingulate cortex, whereas the posterior insula is functionally connected to the primary and secondary somatomotor cortices. Notably, the clusters more strongly connected to the CeA, compared to the BNST, were distributed broadly throughout the insula and appeared to be located in the posterior as well as the dorsal and ventral anterior subdivisions. This differential coupling suggests that, compared to the BNST, the CeA is more strongly communicates more strongly with regions involved with interoceptive processing within multiple functional domains.

The fusiform gyrus is part of the ventral visual processing stream and forms the core system for face perception and decoding, essential for social interactions (Dziobek I, Bahnemann M, Convit A, & Heekeren HR, 2010; Tyler et al., 2013). Previous research suggests that the amygdala interacts with the ventral visual stream during the processing of emotional information (Vuilleumier & Driver, 2007) and the enhanced coupled of the CeA and fusiform may reflect the well-established role of the amygdala in responding to discrete biologically relevant stimuli, such as human faces.

Finally, the post-central gyrus processes somatosensory related information (Shergill et al., 2013). Unfortunately, our functional imaging field of view did not extend into primary somatosensory cortex (see Supplemental Figure 1), and as such, the full extent to which the CeA is differentially coupled with the somatosensory system remains unclear.

Collectively, these results suggest that the CeA is functionally connected to regions which process visual, interoceptive, and somatosensory information more strongly than the BNST. This finding may reflect the particularly important generic role of the amygdala in integrating salience and valence of stimuli for adaptive behavioral responses. Although speculative, this relatively stronger functional association with the coding of sensory characteristics of stimuli and their associated affective value might reflect a closer link with the building blocks of fear learning. However, it should also be noted that the CeA was also more strongly connected to the right supramarginal gyrus, which is involved with a wide array of visuo-spatial processes including attention, saccade eye movements, and grasping (Simon, Mangin, Cohen, Le Bihan, & Dehaene, 2002). As such, it is unlikely that the preferential role of the CeA, compared to the BNST, be limited to strictly sensory domains.

4.3. BNST: preferential coupling with attentional, motivational, and self-referential networks

The BNST, relative to the CeA, exhibited stronger coupling with regions involved in the anticipation of negative events and in the integration of self-referential values to behavior. These targets consisted of clusters in the ventral striatum, paracingulate gyrus, and posterior cingulate cortex (pCC).

The nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus are critical for the acquisition and performance of instrumental actions (Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2009). Although, there is no clear evidence that the BNST has direct anatomical connections with the caudate nucleus, recent research from independent samples has demonstrated that these two structures are strongly coupled at rest (Avery et al., 2014), and that fiber paths from the BNST to the medial prefrontal cortex travel through the head of the caudate (Krüger, Shiozawa, Kreifelts, Scheffler, & Ethofer, 2015). Taken together, the strong coupling of the BNST with the striatum might represent one mechanism underpinning how anxiety can impact motivated behavior (Avery, Clauss, & Blackford, 2016; Stamatakis et al., 2014).

The paracingulate region more coupled with the BNST than CeA was located within the rostral dorsal mPFC. Specifically, this cluster was located on the border of BA 8/32, caudally to areas identified through the conjunction analysis to be coupled with both the CeA and BNST. Meta-analyses have suggested that a similar area of the rostral dorsal mPFC is the most consistently activated region during the conscious appraisal of threat in instructed-fear conditioning paradigms (Mechias et al., 2010). This region has also recently received much attention with regards to negative affect, including anxiety, linking it to the generation and maintenance of threat appraisal (Bijsterbosch, Smith, & Bishop, 2015; Kim, Gee, Loucks, Davis, & Whalen, 2011; Shackman et al., 2011).

Meanwhile, the pCC, is more strongly coupled with the BNST than CeA. The pCC is involved in self-referential mental processes and mind-wandering (Northoff et al., 2006). Taken together, this differential connectivity pattern with structures involved in self-generated thoughts, typical of worry, may suggest a preferential involvement of the BNST with the cognitive aspects of anxiety, relative to the amygdala. However, pCC activity has been linked to other mental activities, including autobiographical memory (Spreng, Mar, & Kim, 2008) and researchers have suggested that the pCC may promote internally-directed cognition or may serve to regulate the focus of attention (Leech & Sharp, 2014). As such, our interpretation that iFC between the BNST and pCC reflects self-referential activity is speculative, and this enhanced connectivity may reflect other internally directed mental processes.

Finally, contrary to our expectation, the hippocampus was not found to be more strongly connected with the BNST than the CeA. The hippocampus is critical for contextual conditioning (Maren et al., 2013), which serves as a model for anxiety (defensive response to diffuse threat) (Davis et al., 2010), and therefore, was expected to be more closely associated with the BNST than the CeA. Although the BNST is strongly coupled with the anterior hippocampus, our results do not support the hypothesis that, compared to the CeA, the BNST is more strongly connected with the neural systems that support contextual threat learning at rest.

4.4. Laterality Effects

We hypothesized that differences in iFC between the CeA and BNST would vary across hemispheres, however, we made no a priori hypotheses concerning the location or directionality of such effect. Although previous research has addressed differences between the iFC of the left and right amygdala, the majority of studies focus on associations between iFC and between subject factors such as gender or mood diagnosis (Hahn et al., 2011; Kilpatrick, Zald, Pardo, & Cahill, 2006; Makovac et al., 2016). Further, prior work which has formally tested for differences between amygdala subregions do not report whole brain analyses testing for effects of CeA laterality (Roy et al., 2009). Nonetheless, findings from animal models and human neuroscience can provide insights into our results.

Research in animals suggests that dopamine and serotonin signaling within the left and right amygdala differentially impact behavior, and that pain processing within CeA, specifically, is lateralized (Andersen & Teicher, 1999; Bradbury, Costall, Domeney, & Naylor, 1985; Ji & Neugebauer, 2009) Additionally, meta-analyses have demonstrated that the left amygdala is more strongly activated than the right amygdala regardless of paradigm and stimulus type (Baas, Aleman, & Kahn, 2004). During the repeated presentation of emotional stimuli, the left amygdala habituates more slowly than the right amygdala which has led researchers to suggest that the left amygdala is specialized for sustained attention to discrete stimuli, whereas the right amygdala is specialized for the dynamic detection of emotional cues (Wright et al., 2001). Meanwhile, research has consistently demonstrated that the vmPFC is critically involved with the extinction of discrete conditioned stimuli during cued aversive Pavlovian learning (Ahs, Kragel, Zielinski, Brady, & LaBar, 2015; Milad et al., 2007; Phelps, Delgado, Nearing, & LeDoux, 2004), and it is possible that the enhanced connectivity between the left CeA and vmPFC reflects the need for enhanced regulation of sustained CeA responses in the left hemisphere.

Alternatively, lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex in primates reduce BNST metabolism and decrease freezing behavior (Fox et al., 2010). In line with this evidence, humans who have sustained damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex exhibit reduced resting metabolism within the BNST (Motzkin et al., 2015), suggesting that in contrast to its role in down-regulating amygdala responses, the vmPFC may serve to up-regulate activity within the BNST. Intriguingly, research suggests that vmPFC lesions impact the metabolism of the right, but not left BNST (Motzkin et al., 2015), and it is possible that the role of the vmPFC in generating BNST responses is reflected in the preferential iFC between the vmPFC and right BNST.

Nonetheless, interactions between seed ROI and hemisphere were also observed within the inferior frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus, and as such it is unclear whether this pattern necessarily reflects the differential impact of regulatory structures on CeA and BNST responses. Future research will be necessary to confirm these patterns and shed light on their functional significance.

4.5. Future Challenges

This study is not without limitations. First, the field of view (FOV) used for functional data collection did not include the most superior aspects of the frontal and parietal lobes (see Supplement F1). As such, these data cannot address whether the CeA and BNST are preferentially coupled with primary somatosensory and motor cortices, respectively. This is important as anatomical tract tracing studies in rodents indicate that the CeA receives a higher number of projections from cortical and sensory-related regions, whereas the BNST shows preferential inputs from motor-related regions (Bienkowski & Rinaman, 2012). Future research will need to fill this gap. Secondly, BNST seeds were hand drawn resulting in a unique seed region for each participant. CeA seeds meanwhile, were based on a standardized template and it is possible that this lack of anatomical specificity impacted the signal to noise ratio in our measurements. Additionally, caution should be used when interpreting clusters which exhibit significant iFC, yet are in close proximity to seed ROIs. Although the Euclidean distance between the BNST and caudate, and the distance between the CeA and lateral nucleus of the amygdala, are large enough that we would not expect these results to be due to smoothing (See Supplementary Results for full details), future research will be needed to replicate the pattern of findings reported here.

Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that the resting-state fMRI approach only informs connectivity patterns at rest. Patterns of connectivity during a task may complement these resting-state maps by challenging the networks of these maps and by providing functional significance. For example, the relative strength of the functional connectivity of the BNST and CeA may appear different during acute threat vs. sustained threat. The present work will help guide future experiments that test functional probes of the BNST and CeA networks. Lastly, findings in healthy participants will need to be contrasted with findings in patients suffering from anxiety or mood disorders, given the central role of the CeA and BNST in emotion perturbations.

4.6. Conclusion

Collectively, the findings of this study suggest that the human CeA is most strongly coupled with the neural systems that coordinate responses to sensory stimuli, whereas BNST is preferentially coupled with regions that support self-representational processes and goal-directed behavior. Additionally, these findings provide initial evidence that the relative strength of CeA and BNST iFC differ across left and right hemispheres, which may suggest differences in the lateralization of function between these nodes of the central extended amygdala. The relative strengths of iFC networks are thought to reflect the history of usage of these networks as well as structural connections between brain regions (Deco et al., 2011; Raichle, 2009). As such, these results can inform hypotheses about the organization of functional resting state networks and may shed light on the relative roles of the CeA and BNST within distributed neural networks that coordinate sensory, emotional, and cognitive responses to threat exposure.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The CeA and BNST have overlapping functional connections

The CeA is more strongly connected to regions involved in sensory processing

The BNST is more strongly connected to regions involved in motivational processing

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Katherine O'Connell, Andrew Davis, and Brendon Nacewicz. This work utilized the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov). This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Mental Health, project number ZIAMH002798 (clinical protocol 02-M-0321, NCT00047853) to CG, and research grants from the National Institutes of Health (DA040717 and MH107444) to AJS. The authors report no competing interest. The author(s) declare that, except for income received from the primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past 3 years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AAhs F, Kragel PA, Zielinski DJ, Brady R, LaBar KS. Medial prefrontal pathways for the contextual regulation of extinguished fear in humans. NeuroImage. 2015;122:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Mishkin M. Projections of the amygdala to the thalamus in the cynomolgus monkey. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;222(1):56–68. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220106. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902220106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitto HJ, Usrey WM. Corticothalamic feedback and sensory processing. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2003;13(4):440–445. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00096-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Serotonin laterality in amygdala predicts performance in the elevated plus maze in rats. Neuroreport. 1999;10(17):3497–3500. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199911260-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadis EA, McDonald RJ. Fornix, medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and mediodorsal thalamic nucleus: Roles in a fear-based context discrimination task. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2006;85(1):71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.08.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery SN, Clauss JA, Blackford JU. The Human BNST: Functional Role in Anxiety and Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):126–141. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.185. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery Suzanne N, Clauss JA, Winder DG, Woodward N, Heckers S, Blackford JU. BNST neurocircuitry in humans. NeuroImage. 2014;91:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas D, Aleman A, Kahn RS. Lateralization of amygdala activation: a systematic review of functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Research Reviews. 2004;45(2):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandler R, Keay KA, Floyd N, Price J. Central circuits mediating patterned autonomic activity during active vs. passive emotional coping. Brain Research Bulletin. 2000;53(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman MG, Peltier S, Nee DE, Kross E, Deldin PJ, Jonides J. Depression, rumination and the default network. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;nsq080 doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq080. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: “liking”, “wanting”, and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski MS, Rinaman L. Common and distinct neural inputs to the medial central nucleus of the amygdala and anterior ventrolateral bed nucleus of stria terminalis in rats. Brain Structure and Function. 2012;218(1):187–208. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0393-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-012-0393-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijsterbosch J, Smith S, Bishop SJ. Functional connectivity under anticipation of shock: Correlates of trait anxious affect versus induced anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2015 doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00825. Retrieved from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/jocn_a_00825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Birn RM, Shackman AJ, Oler JA, Williams LE, McFarlin DR, Rogers GM, et al. Kalin NH. Evolutionarily conserved prefrontal-amygdalar dysfunction in early-life anxiety. Molecular Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):915–922. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.46. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn Rasmus M, Smith MA, Jones TB, Bandettini PA. The respiration response function: the temporal dynamics of fMRI signal fluctuations related to changes in respiration. Neuroimage. 2008;40(2):644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair HT, Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala: a cellular hypothesis of fear conditioning. Learning & Memory. 2001;8(5):229–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury AJ, Costall B, Domeney AM, Naylor RJ. Laterality of dopamine function and neuroleptic action in the amygdala in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24(12):1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90149-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3908(85)90149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey KL, Morrow TJ. Ventral posterior thalamic neurons differentially responsive to noxious stimulation of the awake monkey. Science. 1983;221(4611):675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.6867738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AL, Fair DA, Dosenbach NUF, Miezin FM, Dierker D, Van Essen DC, et al. Petersen SE. Defining functional areas in individual human brains using resting functional connectivity MRI. NeuroImage. 2008;41(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney RE, Joormann J, Eugène F, Dennis EL, Gotlib IH. Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10(4):470–478. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.4.470. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.10.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical Research. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Reynolds RC, Taylor PA. AFNI and Clustering: False Positive Rates Redux. bioRxiv. 2016;065862 [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3(8):655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Watson SJ. Ventral subicular interaction with the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: Evidence for a relay in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;332(1):1–20. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.903320102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Shi C. The extended amygdala: are the central nucleus of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially involved in fear versus anxiety? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;877(1):281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Miles L, Grillon C. Phasic vs sustained fear in rats and humans: role of the extended amygdala in fear vs anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):105–135. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Jirsa VK, McIntosh AR. Emerging concepts for the dynamical organization of resting-state activity in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(1):43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2961. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA. Three Systems of Insular Functional Connectivity Identified with Cluster Analysis. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21(7):1498–1506. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq186. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhq186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Swanson LW. Organization of axonal projections from the anterolateral area of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2004;468(2):277–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.10949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziobek I, Bahnemann M, Convit A, Heekeren HR. THe role of the fusiform-amygdala system in the pathophysiology of autism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):397–405. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.31. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H. Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(28):7900–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602413113. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602413113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders—non-patient edition. New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonov V, Evans AC, Botteron K, Almli CR, McKinstry RC, Collins DL, et al. Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. NeuroImage. 2011;54(1):313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonov VS, Evans AC, McKinstry RC, Almli CR, Collins DL. Unbiased nonlinear average age-appropriate brain templates from birth to adulthood. NeuroImage. 2009;47:S102. [Google Scholar]

- Fox AS, Shelton SE, Oakes TR, Converse AK, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. Orbitofrontal cortex lesions alter anxiety-related activity in the primate bed nucleus of stria terminalis. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(20):7023–7027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5952-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(9):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana MA, Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Vervliet B, Cardoner N, Àvila-Parcet A, Radua J. Neural signatures of human fear conditioning: an updated and extended meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Molecular Psychiatry. 2016;21(4):500–508. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.88. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;44(1):162–167. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<162::aid-mrm23>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso A, Cambiaghi M, Concina G, Sacco T, Sacchetti B. Auditory cortex involvement in emotional learning and memory. Neuroscience. 2015;299:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn A, Stein P, Windischberger C, Weissenbacher A, Spindelegger C, Moser E, et al. Lanzenberger R. Reduced resting-state functional connectivity between amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in social anxiety disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley KM, Herbert H, Moga MM, Saper CB. Efferent projections of the infralimbic cortex of the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;308(2):249–276. doi: 10.1002/cne.903080210. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.903080210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton C, Josephs O, Stadler J, Featherstone E, Reid A, Speck O, et al. Weiskopf N. The impact of physiological noise correction on fMRI at 7T. Neuroimage. 2011;57(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaisinghani S, Rosenkranz JA. Repeated social defeat stress enhances the anxiogenic effect of bright light on operant reward-seeking behavior in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015;290:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Neugebauer V. Hemispheric Lateralization of Pain Processing by Amygdala Neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;102(4):2253–2264. doi: 10.1152/jn.00166.2009. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00166.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Saad ZS, Simmons WK, Milbury LA, Cox RW. Mapping sources of correlation in resting state FMRI, with artifact detection and removal. Neuroimage. 2010;52(2):571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick LA, Zald DH, Pardo JV, Cahill LF. Sex-related differences in amygdala functional connectivity during resting conditions. NeuroImage. 2006;30(2):452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Gee DG, Loucks RA, Davis FC, Whalen PJ. Anxiety dissociates dorsal and ventral medial prefrontal cortex functional connectivity with the amygdala at rest. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 2011;21(7):1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq237. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhq237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger O, Shiozawa T, Kreifelts B, Scheffler K, Ethofer T. Three distinct fiber pathways of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis to the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Cortex. 2015;66:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8(7):2517–2529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech R, Sharp DJ. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain. 2014;137(1):12–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt162. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeholm M, O'Doherty JP. Contributions of the striatum to learning, motivation, and performance: an associative account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(9):467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.07.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makovac E, Meeten F, Watson DR, Herman A, Garfinkel SN, Critchley HD, Ottaviani C. Alterations in Amygdala-Prefrontal Functional Connectivity Account for Excessive Worry and Autonomic Dysregulation in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Phan KL, Liberzon I. The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(6):417–428. doi: 10.1038/nrn3492. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechias ML, Etkin A, Kalisch R. A meta-analysis of instructed fear studies: implications for conscious appraisal of threat. NeuroImage. 2010;49(2):1760–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Wright CI, Orr SP, Pitman RK, Quirk GJ, Rauch SL. Recall of Fear Extinction in Humans Activates the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampus in Concert. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzkin JC, Philippi CL, Oler JA, Kalin NH, Baskaya MK, Koenigs M. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex damage alters resting blood flow to the bed nucleus of stria terminalis. Cortex. 2015;64:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.11.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T, Brett M, Andersson J, Wager T, Poline JB. Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. NeuroImage. 2005;25(3):653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain—A meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. NeuroImage. 2006;31(1):440–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okon-Singer H, Hendler T, Pessoa L, Shackman AJ. The neurobiology of emotion–cognition interactions: fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2015;9:58. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oler JA, Birn RM, Patriat R, Fox AS, Shelton SE, Burghy CA, et al. Kalin NH. Evidence for coordinated functional activity within the extended amygdala of non-human and human primates. NeuroImage. 2012;61(4):1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oler JA, Tromp DPM, Fox AS, Kovner R, Davidson RJ, Alexander AL, et al. Fudge JL. Connectivity between the central nucleus of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the non-human primate: neuronal tract tracing and developmental neuroimaging studies. Brain Structure and Function. 2016:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1198-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-016-1198-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Olmos JS, Heimer L. The concepts of the ventral striatopallidal system and extended amygdala. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;877(1):1–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Quirk GJ, Ledoux JE. New vistas on amygdala networks in conditioned fear. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92(1):1–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00153.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Sambugaro E, Torti T, Danelli L, Ferri F, Scialfa G, et al. Sassaroli S. Neural correlates of worry in generalized anxiety disorder and in normal controls: a functional MRI study. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(01):117–124. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, LeDoux JE. Extinction learning in humans: role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron. 2004;43(6):897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME. A Paradigm Shift in Functional Brain Imaging. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(41):12729–12734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4366-09.2009. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4366-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WW. Fearlike behavior elicited from dorsomedial thalamus of cat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1962;55(2):191–197. doi: 10.1037/h0040360. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Shehzad Z, Margulies DS, Kelly AMC, Uddin LQ, Gotimer K, et al. Milham MP. Functional connectivity of the human amygdala using resting state fMRI. NeuroImage. 2009;45(2):614–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Markowitsch HJ. Involvement of the amygdala in learning and memory: A critical review, with emphasis on anatomical relations. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1985;99(2):342–380. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.2.342. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.99.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Fox AS. Contributions of the Central Extended Amygdala to Fear and Anxiety. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(31):8050–8063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0982-16.2016. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0982-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, Davidson RJ. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(3):154–167. doi: 10.1038/nrn2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Papademetris X, Constable RT. Graph-theory based parcellation of functional subunits in the brain from resting-state fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2010;50(3):1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shergill SS, White TP, Joyce DW, Bays PM, Wolpert DM, Frith CD. Modulation of somatosensory processing by action. NeuroImage. 2013;70:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CJ, Cassell Md. Cortical, thalamic, and amygdaloid connections of the anterior and posterior insular cortices. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;399(4):440–468. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981005)399:4<440::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981005)399:4<440∷AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM, Liberzon I. The Neurocircuitry of Fear, Stress, and Anxiety Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35(1):169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon O, Mangin JF, Cohen L, Le Bihan D, Dehaene S. Topographical Layout of Hand, Eye, Calculation, and Language-Related Areas in the Human Parietal Lobe. Neuron. 2002;33(3):475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00575-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim ASN. The Common Neural Basis of Autobiographical Memory, Prospection, Navigation, Theory of Mind, and the Default Mode: A Quantitative Meta-analysis. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;21(3):489–510. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21029. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.21029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis AM, Sparta DR, Jennings JH, McElligott ZA, Decot H, Stuber GD. Amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis circuitry: implications for addiction-related behaviors. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, Moser EI. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2014;15(10):655–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3785. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GM, Apergis J, Bush DEA, Johnson LR, Hou M, Ledoux JE. Lesions in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis disrupt corticosterone and freezing responses elicited by a contextual but not by a specific cue-conditioned fear stimulus. Neuroscience. 2004;128(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrisi S, O'Connell K, Davis A, Reynolds R, Balderston N, Fudge JL, et al. Ernst M. Resting state connectivity of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis at ultra-high field. Human Brain Mapping. 2015;36(10):4076–4088. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22899. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Chiu S, Zhuang J, Randall B, Devereux BJ, Wright P, et al. Taylor KI. Objects and Categories: Feature Statistics and Object Processing in the Ventral Stream. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25(10):1723–1735. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00419. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyszka JM, Pauli WM. In vivo delineation of subdivisions of the human amygdaloid complex in a high-resolution group template. Human Brain Mapping. 2016 doi: 10.1002/hbm.23289. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hbm.23289/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman V, Rosati AG, Taren AA, Huettel SA. Resolving response, decision, and strategic control: evidence for a functional topography in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(42):13158–13164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2708-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Driver J. Modulation of visual processing by attention and emotion: windows on causal interactions between human brain regions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2007;362(1481):837–855. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2092. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J, Morris RW, Bouton ME. Effects of bed nucleus of the stria terminalis lesions on conditioned anxiety: Aversive conditioning with long-duration conditional stimuli and reinstatement of extinguished fear. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120(2):324–336. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CI, Fischer Hakan, Whalen PJ, McInerney SC, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Differential prefrontal cortex and amygdala habituation to repeatedly presented emotional stimuli. Neuroreport. 2001;12(2):379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.