Abstract

Objective

Neighborhood socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities exist in the amount and type of tobacco marketing at retail, but most studies are limited to a single city or state, and few have examined flavored little cigars. Our purpose is to describe tobacco product availability, marketing, and promotions in a national sample of retail stores and to examine associations with neighborhood characteristics.

Methods

At a national sample of 2,230 tobacco retailers in the contiguous US, we collected in-person store audit data on: Availability of products (e.g., flavored cigars), quantity of interior and exterior tobacco marketing, presence of price promotions, and marketing with youth appeal. Observational data were matched to census tract demographics.

Results

Over 95% of stores displayed tobacco marketing; the average store featured 29.5 marketing materials. 75.1% of stores displayed at least one tobacco product price promotion, including 87.2% of gas/convenience stores and 85.5% of pharmacies. 16.8% of stores featured marketing below three feet, and 81.3% of stores sold flavored cigars, both of which appeal to youth. Stores in neighborhoods with the highest (vs. lowest) concentration of African-American residents had more than two times greater odds of displaying a price promotion (OR=2.1) and selling flavored cigars (OR=2.6). Price promotions were also more common in stores located in neighborhoods with more residents under age 18.

Conclusions and relevance

Tobacco companies use retail marketing extensively to promote their products to current customers and youth, with disproportionate targeting of African Americans. Local, state, and federal policies are needed to counteract this unhealthy retail environment.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, point of sale, retail, marketing, advertising, disparities

Introduction

Despite recent progress in reducing overall tobacco use, disparities by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity persist.1 Data from the 2013–2014 National Adult Tobacco Survey indicate that about 32% of adults without a high school degree or who earn less than $20,000 per year used some form of tobacco, compared to about 10% of college graduates and 12% of people with annual incomes of $100,000 of more.2 In 2015, current tobacco use among middle school students was higher for Hispanic students (10.6%) compared with Non-Hispanic White (6.3%) or Black students (6.6%).3

Furthermore, use of specific tobacco products is growing, especially among youth. The 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that 63.5% of current adolescent smokers used flavored little cigars, and 53.6% used menthol cigarettes.4 In 2015, cigar use was highest among Black high school students compared with both White and Hispanic students.3 An estimated 5.6 million youth under age 18 in the United States (US) will die prematurely from tobacco-related illnesses if present adolescent smoking trends continue.5

The retail environment provides the tobacco industry with extensive opportunities to market current and emerging products to adults and youth. In 2014, the largest US cigarette and smokeless tobacco companies spent $8.2 billion in marketing and promotion at the point of sale (91% of annual marketing dollars), with the majority of this spending on promotions to reduce the price of tobacco products.6,7 In the National Youth Tobacco Survey, 76.2% of US students in grades 6–12 reported seeing tobacco advertising in stores.8 Among youth, greater exposure to cigarette advertising is associated with more positive attitudes toward smoking,9 greater susceptibility to smoking,10 and smoking initiation.10,11 Among adults, exposure to point of sale (POS) marketing is linked to greater cravings among current smokers,10 and smokers who quit are more likely to relapse if they live near a tobacco retailer.12 Almost 20% of current smokers use promotions or coupons to reduce cigarette prices,13 and these price minimizing behaviors are associated with fewer quit attempts and lower rates of quitting smoking.14–16

Tobacco industry documents illustrate marketing strategies to target racial and ethnic minorities17 and youth18 by exploiting the retail environment as the main channel to communicate with consumers.19 More POS tobacco advertising has been documented in predominantly African-American20,21 and low-income neighborhoods,20,22–24 near high schools with higher proportions of African-American,25 Hispanic and low-income students26 and in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of youth.25,27 These studies, however, are based on store samples from single cities or states, or focus primarily on marketing for a specific tobacco product. A recent systematic review 28 of tobacco retail studies found only four that included measures of cigar availability.

This is the first national study to estimate POS marketing and promotions for both cigarettes and other tobacco products (e.g. cigars, e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco), as well as the availability and marketing of products with youth appeal such as flavored cigars and advertising near candy. We also explore whether previous observations of marketing disparities observed in cities occur on a national level. The purpose of this paper is to (1) report the amount and types of tobacco marketing materials and promotions overall and by store type in a representative sample of US stores in the contiguous US that sell cigarettes and (2) examine whether tobacco marketing, promotions and flavored cigar availability are associated with neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

This study used data from Advancing Science and Policy in the Retail Environment (ASPiRE), funded by the National Cancer Institute’s State and Community Tobacco Control Research Initiative. ASPiRE is a consortium of researchers from the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis, the Stanford Prevention Research Center, and the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Sample

Selection of counties

To obtain a representative sample of tobacco retailers in the contiguous US, we employed a two-stage sampling design. In the first stage, we selected counties with minimal replacement using a probability proportionate to size (PPS) method developed by Chromy.29 We used 2010 Census data to identify all 3,109 counties and selected 100 with a probability of selection proportional to county population. In the final sample of 100 counties, 97 were unique.

Random selection of stores

The US does not have a mandatory licensing system for selling tobacco products; therefore no national sampling frame exists. To create a sampling frame, we purchased lists from two secondary data sources, Reference USA and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), which provided a list from Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. We then processed these lists using an approach validated in a previous study.30 Using NAICS codes, we selected ten store types that accounted for 98% of tobacco product sales in payroll establishments in the 2007 Census of Retail Trade (i.e., tobacco stores; supermarkets and grocery; convenience stores; gas stations with convenience stores; other gas stations; warehouse clubs and supercenters; news dealers and newsstands; beer, wine and liquor stores; pharmacies; discount department stores).31

Before sampling, we excluded chains known not to sell tobacco products (e.g., Target, Whole Foods). Pilot testing in a previous study30 showed that only Wal-Mart among the discount department stores, and only chain/retail stores among pharmacies were likely to sell tobacco products; therefore we included only Wal-Mart and the top 50 retail pharmacies in these categories. The resulting lists from the two secondary sources were merged and de-duplicated. Based on our power analysis, our goal was to complete audits in at least 2,000 stores. We randomly selected up to 55 stores in each of our selected counties, and called the list in order until we verified addresses and cigarette availability in 24 per county. Stores that could not be reached after three attempts, or that did not sell cigarettes, were deemed ineligible. Seven counties produced fewer than 24 verified stores even after calling all likely retailers in the county, resulting in a final sample of 2,346.

Data collection

Following general recommendations by Lee and colleagues,28 our trained data collectors used standardized approaches to conducting exterior and interior audits of tobacco marketing materials and promotions as well as tobacco product availability and placement. Data for each store were collected in person by a trained auditor using an electronic audit form designed for this study and programmed onto Apple iPads© using iSurvey©. Prior to conducting audits, 13 data collectors received a 5-hour in-person training that included field practice. All audits were conducted between June and October 2012. The University of North Carolina Office of Human Research Ethics determined that the study did not constitute human subjects research (12-0765).

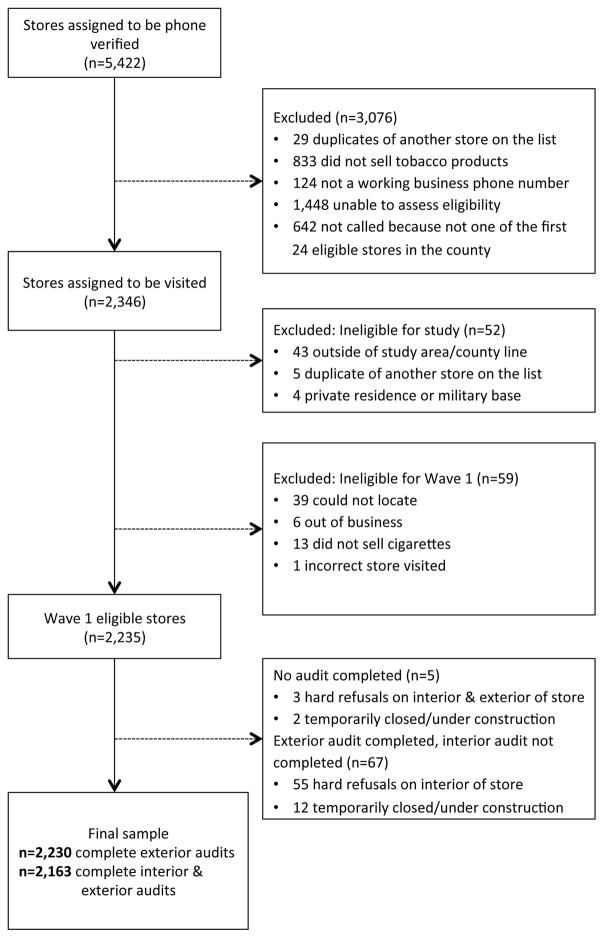

Figure 1 shows that exterior audits were completed at 2,230 stores, and among those, interior audits were completed at 2,163 stores (97.00% of eligible stores). Interior audits were not completed when store clerks refused permission to complete the audit or when the store was temporarily closed. Analyses of exterior characteristics use the larger sample (n=2,230), and all other analyses use stores with complete data for interior and exterior (n=2,163). On average, there were 22.3 complete stores successfully audited per county (min=6, max=67 where a county was sampled three times).

Figure 1.

WAVE 1 SAMPLING DIAGRAM, ASPIRE STUDY, 97 COUNTIES IN THE CONTINENTAL US (data collected 06/2012– 10/2012)

Measures

Tobacco marketing materials

Data collectors counted and coded branded signs (professional signs that include any imagery and font associated with tobacco company brand insignia), branded displays (portable units that hold tobacco products and can be moved easily), branded shelving units (large shelving units or power walls with a header display that are typically affixed to the wall or floor), and branded functional items (industry produced items with a brand or company logo that serve a functional purpose in addition to advertising the product, such as a Marlboro trash can). Data collectors recorded whether each marketing material was: 1) specific to cigarettes or other non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTP), such as cigarillos, smokeless tobacco, and e-cigarettes, and 2) located on the interior or exterior of the store, including in the parking lot. Total marketing materials measures the sum of interior and exterior.

Tobacco price promotions

Price promotions were defined as any multi-pack special (e.g., buy one get one free) or special price (e.g., $1.00 discount), and these were coded by product type and location (interior/exterior).

Tobacco products and marketing with youth appeal

We created four dichotomous indicators: 1) flavored cigar availability; 2) single cigar availability; 3) flavored and unflavored smokeless product availability (including snus); 4) tobacco products displayed near (i.e., within 12 inches of) candy, and 5) interior marketing materials placed at or below three feet. Cigars were defined to include cigarillos, little cigars, and large cigars. We considered flavors to include any flavor except tobacco or menthol/mint, which matches Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Product definitions.

Inter-rater reliability was assessed at 165 stores visited twice within an average of 30 days (range 6 to 49 days) in a convenience sample of 6 counties. Reliability for marketing materials was calculated using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and was 0.77 for total, 0.77 for interior, and 0.57 for exterior. Inter-rater reliability for any price promotions and flavored cigars sold was calculated using Cohen’s kappa and was 0.41, and 0.63, respectively.

Countermarketing

We observed whether stores displayed an interior graphic health warning sign.

Store type

We assessed whether marketing and product availability differed by type of store, and included it as a covariate to ensure that differences by neighborhood demographics did not simply reflect the types of stores in the neighborhood. Each store was categorized in the field using one of ten North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes, or as ‘other’ if no code seemed appropriate. We consolidated store types into seven categories: supermarket/grocery stores; gas station with or without convenience store (gas/convenience); convenience store (without a gas station); pharmacy/drug store; warehouse club/supercenter (including Wal-Mart); liquor store, and other (e.g., newsstands and other store types).

Store neighborhood characteristics

Using the latitude and longitude recorded by iSurvey©, stores were joined to their corresponding census tract using ArcGIS and Tiger/Line® Shape files from the 2010 US Census. Four measures for the store’s census tract were used to assess neighborhoods demographics: median household income (grouped into tens of thousands), percent of the population that is Non-Hispanic Black (identifying as one race only), Hispanic, and under age 18. These measures were obtained from the 2011 American Community Survey 5 year estimates (Geolytics). Race and ethnicity distributions were categorized into quartiles to ease interpretation of differences by neighborhood demographics. A Census indicator of region (West, South, Northeast, and Midwest) was also included as a control variable in multivariate analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We created national estimates of tobacco marketing materials, promotions and products by applying sampling weights that accounted for both county and store selection in the sampling design and non-response. We used mixed-effects modeling using HLM 732 to examine 1) whether store and neighborhood characteristics were associated with four outcomes: total tobacco marketing materials, price promotion availability, flavored cigar availability, and smokeless product availability; and 2) whether any observed relationships were maintained after controlling for store type because store type distributions are often related to neighborhood demographics. Of the youth appeal indicators, we chose to model neighborhood effects for flavored cigars, given the growing popularity of these products. A mixed-effects linear model was used for the continuous outcome (total marketing materials) and a generalized mixed-effects model was used for the dichotomous outcomes (presence of price promotion and availability of flavored cigars and smokeless). The mixed-effects models accounted for the clustering of stores (level 1, n=2,162) within counties (level 2, n=97) that resulted from our sampling design (total marketing materials, ICC=0.18; any promotion, ICC=0.13; 33 flavored cigars, ICC=0.11; smokeless, ICC=0.11). Clustering of stores in tracts was minimal: 80% had only one observed store. All models employed both store- and county-level weights. Median household income was log transformed and continuous variables were grand mean centered.

Results

Estimates of tobacco marketing at stores that sell cigarettes in the contiguous US are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of marketing materials and promotions (interior and exterior) for cigarettes and NCTP, and Table 2 specifies marketing materials, promotions, and youth appeal indicators by store type.

Table 1.

Estimates of branded tobacco marketing materials and promotions at tobacco outlets in the contiguous US (N =2,230)a, 2012

| Cigarettes | Non-cigarette tobacco products | Total (n=2,162) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Interior (n=2,162) | Exterior (n=2,229) | Interior (n=2,162) | Exterior (n=2,229) | ||

| Total marketing materials, mean (95% CI) | 14.5 (14.0, 15.0) | 2.5 (2.3, 2.7) | 11.7 (10.9, 12.4) | 0.9 (0.8,1.0) | 29.5 (28.3, 30.7) |

| Signs | 12.3 (11.9, 12.7) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.6) | 6.6 (6.2, 7.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | 22.2 (21.3, 23.0) |

| Functional items | 0.2 (0.2, 0.2) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | 0.14 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.5) |

| Displays | 0.4 (0.3, 0.4) | na | 4.3 (3.8, 4.7) | na | 4.6 (4.2, 5.1) |

| Shelving units | 1.6 (1.5, 1.7) | na | 0.66 (0.6, 0.7) | na | 2.3 (2.2, 2.4) |

| Any price promotions, % (95% CI) | 75.0 (73.0, 77.1) | ||||

| Special price | 66.2 (64.0, 68.4) | 23.3 (21.4, 25.2) | 28.8 (26.6, 30.9) | 3.7 (2.8, 4.5) | 71.2 (69.1, 73.3) |

| Multi-pack discount | 24.6 (22.7, 26.5) | 6.6 (5.6, 7.7) | 17.8 (16.1, 19.5) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.1) | 35.8 (33.6, 38.0) |

| Stores with graphic health warning signs, % (95% CI) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4) | ||||

N for interior and total measures is 2,163; N for exterior measures is 2,230. All estimates are weighted.

Table 2.

Branded tobacco marketing materials and indicators or youth appeal by store type at tobacco outlets in the contiguous US (N =2,230), 2012

| Marketing Materials | Youth Appeal

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total marketing materials |

Any exterior marketing |

Any interior marketing |

Any price promotion |

Flavored cigars sold |

Single cigars sold | Any interior marketing below 3 ft. |

Any product within 12 in. of candy |

||

|

|

|||||||||

| Store Type | nb | Mean (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| Gas stations with or without convenience store | 945 | 39.5 (37.9, 41.2) | 76.2 (73.1, 79.2) | 99.3 (98.7, 99.8) | 87.2 (84.7, 89.8) | 92.8 (90.9, 94.7) | 90.2 (87.9, 92.2) | 20.2 (17.3, 23.0) | 13.4 (11.0, 15.8) |

| Supermarkets & other grocery | 399 | 15.9 (14.0, 17.8) | 22.7 (17.8, 27.6) | 90.0 (86.8, 93.2) | 57.4 (51.8, 63.0) | 61.4 (55.8, 66.9) | 54.5 (48.9, 60.2) | 12.9 (9.5, 16.3) | 4.1 (2.2, 6.1) |

| Convenience stores (without gas) | 258 | 28.0 (25.0, 31.0) | 64.4 (58.1, 70.6) | 93.8 (90.5, 97.2) | 73.2 (67.0, 79.4) | 84.4 (79.3, 89.4) | 81.0 (75.8, 86.3) | 17.3 (12.3, 22.2) | 11.4 (7.1, 15.8) |

| Pharmacy and drug stores | 236 | 16.0 (14.7, 17.2) | 1.4 (0.0, 3.1) | 98.9 (97.4, 100.0) | 85.5 (80.3, 90.6) | 90.3 (86.2, 94.5) | 87.7 (83.1, 92.3) | 0.0 | 1.2 (0.0, 2.6) |

| Beer, wine, and liquor stores | 224 | 13.6 (11.3, 15.9) | 37.9 (30.7, 45.0) | 83.6 (76.9, 90.2) | 50.9 (43.4, 58.5) | 51.3 (43.7, 59.0) | 53.3 (45.6, 60.9) | 14.1 (9.1, 19.1) | 10.5 (6.2, 14.7) |

| Tobacco stores | 93 | 76.7 (62.0, 91.4) | 81.1 (72.0, 90.0) | 95.2 (89.8, 100.0) | 79.4 (70.2, 88.5) | 98.0 (95.2, 100.0) | 96.8 (92.2, 100.0) | 59.4 (48.1, 70.8) | 26.5 (16.0, 36.9) |

| Warehouse clubs, supercenters and Walmart | 56 | 19.2 (15.1, 23.3) | 1.2 (0.0, 3.5) | 95.2 (89.8, 100.0) | 51.5 (37.6, 65.4) | 79.3 (68.1, 90.5) | 43.1 (29.4, 56.8) | 5.1 (0.0, 10.9) | 0.0 |

| Other establishment type | 16 | 6.4 (1.9, 10.9) | 27.4 (3.7, 51.2) | 77.5 (56.8, 98.2) | 33.2 (6.5, 59.9) | 29.6 (4.4, 54.7) | 35.6 (9.6, 61.7) | 18.0 (0.0, 37.2) | 0.0 |

| All stores | 2230c | 29.5 (28.3, 30.7) | 51.5 (49.3, 53.9) | 95.1 (94.0, 96.1) | 75.1 (73.0, 77.1) | 81.3 (79.4, 83.2) | 77.5 (75.5, 79.5) | 16.8 (15.1, 18.5) | 10.0 (8.6, 11.3) |

n for interior and total measures is 2,163, N for exterior measures is 2,230;

Unweighted count of outlet type, all other data are weighted;

Stores do not sum to 2,230 because 2 outlets were missing outlet type.

Marketing materials

Stores had an average of 29.5 (95% CI=28.3, 30.7) total marketing materials, with more materials on the interior than the exterior and more for cigarettes than NCTPs (Table 1). Among these, interior signs were the most common (cigarette 12.3, 95% CI=11.9, 12.7; NCTP 6.6, 95% CI=6.2, 7.0) followed by NCTP displays (4.3, 95% CI=3.8, 4.7) and cigarette shelving units (1.6, 95% CI=1.5, 1.7). Functional items were uncommon, as were graphic health warning signs.

Table 2 shows that nearly all (95.1%) of the stores displayed tobacco marketing materials on the interior, exterior or both (95% CI=94.0%, 96.1%). Not surprisingly, tobacco stores contained the most marketing materials (mean=76.7, 95% CI=62.0, 91.4), followed by gas/convenience stores (mean=39.5, 95% CI=37.9, 41.2) and convenience stores (mean=28.0, 95% CI=25.0–31.0). More than half of all gas/convenience stores, convenience stores, and tobacco stores marketed tobacco products outside, whereas just under a quarter of supermarkets, and fewer than 2% of pharmacies or warehouse clubs did.

Price promotions

Three quarters of stores displayed at least one tobacco price promotion (95% CI=73.0%, 77.1%); 71.2% displayed special prices (95% CI=69.1%, 73.3%) and 35.8% indicated multi-pack offers, such as buy one pack, get one free (95% CI=33.6%, 38.0%) (Table 2). Price promotions were common at all store types. Nearly 9 out 10 gas/convenience stores and pharmacies, 8 out of 10 tobacco stores, and 7 out of 10 convenience stores offered special prices or multipack discounts. Promotions were also present at more than half of supermarkets, warehouse clubs, and liquor stores.

Youth appeal

Flavored cigars were sold in 81.3% of stores (95% CI=79.4%, 83.2%), and single cigars (flavored or unflavored) were sold in 77.5% of stores (95% CI=75.5%, 79.5%); both products were widely available across store types..

Overall, 16.8% of stores displayed tobacco ads below 3 feet (95% CI=15.1%, 18.5%) and 10.0% (95% CI=8.6%, 11.3%) displayed tobacco products near candy. Rates were similar or slightly higher in store types that children are likely to visit34 such as gas/convenience and convenience stores.

Associations of neighborhood characteristics with tobacco marketing materials, promotions and products

Table 3 shows the results for four outcomes: tobacco marketing materials, any price promotions, any flavored cigars sold, and any smokeless sold, each modeled as a function of neighborhood demographics and region. Each outcome was modeled with and without store type as a covariate. For all four dependent variables, adding store type to the model (Models 2, 4, 6 and 8) results in a statistically significant improvement in model fit over Models 1, 3, 5 and 7 respectively as determined by using a log likelihood ratio test (p <0.01 for each model comparison, Table 3).

Table 3.

Store and neighborhood predictors of tobacco product marketing materials, price promotions, and flavored cigars at tobacco outlets in the contiguous US (N = 2,163), 2012

| Total marketing materials | Any price promotion | Flavored cigar availability | Smokeless Availability | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| β | (95% CI) | β | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 19.7 | (10.6,28.9) | 28.7 | (20.2, 37.2) | 1.8 | (1.2,2.9) | 4.4 | (2.4,7.9) | 5.5 | (3.1,9.6) | 15.7 | (7.7,32.4) | 2.9 | (1.9,4.4) | 8.8 | (5.4,14.1) |

| Level 1 (n=2163 stores) | ||||||||||||||||

| Store type | ||||||||||||||||

| Gas Station with or without convenience store (ref) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||||||

| Supermarket & other grocery | −22.3 | (−29.6, −15.0) | 0.1 | (0.1,0.2) | 0.1 | (0.09,0.2) | 0.2 | (0.1,0.2) | ||||||||

| Convenience store (without gas) | −9.1 | (−14.4, −3.8) | 0.4 | (0.3,0.6) | 0.6 | (0.3,0.9) | 0.3 | (0.2,0.4) | ||||||||

| Pharmacy and drug stores | −24.2 | (−27.7, −20.7) | 1.0 | (0.7,1.6) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.3) | 0.4 | (0.3,0.6) | ||||||||

| Beer, wine, and liquor stores | −24.3 | (−29.5, −19.2) | 0.1 | (0.1,0.2) | 0.1 | (0.1,0.1) | 0.1 | (0.1,0.1) | ||||||||

| Tobacco store | 61.8 | (27.8, 95.7) | 0.4 | (0.2,0.9) | 3.5 | (0.6,21.5) | 0.5 | (0.3,1.0) | ||||||||

| Warehouse clubs, supercenters and Walmart | −22.0 | (−27.5, −16.6) | 0.1 | (0.1,0.3) | 0.3 | (0.1,0.6) | 0.8 | (0.3,2.5) | ||||||||

| Other establishment type | −40.4 | (−50.5, −30.3) | 0.03 | (0.0,0.1) | 0.02 | (0.0,0.1) | 0.03 | (0.01,0.1) | ||||||||

| Neighborhood (tract) characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic, % | ||||||||||||||||

| Q1: < 2.02% (ref) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Q2: 2.02–5.98% | 1.0 | (−6.9, 9.0) | −0.3 | (−7.1, 6.6) | 0.9 | (0.6,1.2) | 1.1 | (0.7,1.7) | 0.7 | (0.4,1.0) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.3) | 0.6 | (0.4,0.9) | 0.7 | (0.5,1.1) |

| Q3: 5.98–16.8% | −3.8 | (−9.6, 2.1) | −4.0 | (−9.5, 1.5) | 1.1 | (0.7,1.6) | 1.2 | (0.7,2.0) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.3) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.4) | 0.8 | (0.6,1.2) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.2) |

| Q4: > 16.8% | −3.0 | (−10.8,4.8) | −3.4 | (−10.5, 3.7) | 0.8 | (0.5,1.3) | 1.0 | (0.6,1.6) | 0.7 | (0.4,1.1) | 0.8 | (0.3,1.3) | 0.4 | (0.3,0.7) | 0.5 | (0.3,0.8) |

| non-Hispanic Black, % | ||||||||||||||||

| Q1: < 1.01% (ref) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Q2: 1.01–4.96% | 2.9 | (−0.4, 6.2) | 3.0 | (−1.4, 7.3) | 1.7 | (1.2,2.4) | 1.8 | (1.2,2.6) | 1.5 | (1.1,2.2) | 1.6 | (1.0,2.4) | 1.2 | (0.8,1.8) | 1.2 | (0.8,1.9) |

| Q3: 4.96–15.8% | 7.7 | (−0.1,15.5) | 8.6 | (2.5, 14.8) | 1.7 | (1.1,2.4) | 1.6 | (1.0,2.3) | 1.4 | (1.0,2.1) | 1.3 | (0.8,2.2) | 1.2 | (0.8,1.6) | 1.1 | (0.8,1.6) |

| Q4: > 15.8% | 1.3 | (−4.1, 6.8) | 5.2 | (−2.4, 12.8) | 1.8 | (1.2,2.7) | 2.1 | (1.3,3.4) | 2.0 | (1.2,3.5) | 2.6 | (1.3,5.1) | 0.7 | (0.5,1.0) | 0.7 | (0.5,1.0) |

| Median household income, $10,000 | −0.2 | (−1.6, 1.1) | 0.6 | (−0.8, 2.1) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) | 0.9 | (0.9,1.0) | 0.9 | (0.9,1.0) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) |

| Population under age 18, % | 0.2 | (−0.2, 0.6) | −0.2 | (−0.5, 0.1) | 1.0 | (1.01,1.04) | 1.0 | (1.01,1.05) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.0) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.01) | 1.0 | (1.0,1.01) |

| Level 2 (n=97 counties) | ||||||||||||||||

| Region | ||||||||||||||||

| West (ref) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Northeast | 11.8 | (−4.1,27.7) | 8.6 | (−5.0, 22.3) | 1.8 | (1.0,3.3) | 2.2 | (1.1,4.4) | 0.5 | (0.3,0.9) | 0.5 | (0.3,0.9) | 0.5 | (0.3,0.9) | ||

| Midwest | 10.1 | (1.0, 19.2) | 7.9 | (−0.1, 15.8) | 2.2 | (1.2,3.9) | 2.2 | (1.1,4.1) | 0.7 | (0.4,1.3) | 0.6 | (0.3,1.2) | 1.0 | (0.5,2.2) | ||

| South | 15.9 | (6.1,25.7) | 11.7 | (2.5, 20.9) | 1.5 | (0.9,2.4) | 1.2 | (0.7,2.1) | 1.7 | (1.0,2.9) | 1.4 | (0.7,2.7) | 1.0 | (0.5,2.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Bold indicates significance at p<0.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| AIC | 20626 | 19768 | 6218 | 5960 | 5870 | 5600 | 6148 | 5894 | ||||||||

| χ 2 | 872 | 272 | 284 | 254 | ||||||||||||

| P value (for model comparison) | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

Marketing materials

Stores located in neighborhoods in the third quartile of percentage of non-Hispanic Black residents displayed significantly more marketing materials than stores in neighborhoods with the lowest percentage of non-Hispanic Black residents when store type was added to the model (Table 3, Model 2) (B=8.6, p=.02).

Price promotions

The odds of displaying a promotion were 1.8 times higher (95% CI=1.2, 2.7) in stores located in neighborhoods with the highest vs. lowest percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks (Table 3, Model 3). After adjusting for store type, the association persisted (OR=2.1, 95% CI= 1.3, 3.4) (Table 3, Model 4). Stores located in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of youth had greater odds of featuring price promotions (OR=1.03, 95% CI=1.00, 1.05). Neither the percentage of Hispanic residents nor median household income was associated with a price promotion being displayed. All store types had significantly lower odds of displaying a promotion compared with gas/convenience stores, except pharmacies, which did not differ significantly from gas/convenience stores (Table 3, Model 4).

Flavored cigar availability

Similar to the findings for price promotions, stores in the second and fourth quartile of the percentage of non-Hispanic Black residents had significantly higher odds of selling flavored cigars compared to stores in the first quartile (OR=1.5 and 2.0, respectively), (Table 3, Model 5). After adjusting for store type, the association was significant for these quartiles, with stores in quartile 4 having 2.6 times greater odds of flavored cigar availability compared to stores in quartile 1 (95% CI=1.3, 5.1), (Table 3, Model 6). Stores in quartile two for percent of Hispanic residents, as well as stores in areas with higher median household incomes, had significantly lower odds of selling flavored cigars (OR=0.6, 0.9 respectively) but these associations were non-significant after adjusting for store type (Table 3, Models 5–6). The percentage of the population under age 18 was not significantly associated with flavored cigar availability. All store types had significantly lower odds of selling flavored cigars compared with gas/convenience stores, with the exception of tobacco stores and pharmacies, which did not differ significantly from gas/convenience stores.

Smokeless product availability

The odds of a store selling smokeless tobacco products (including snus) was lower in neighborhoods in the highest quartile of Hispanic residents, compared with the lowest (OR=0.5, 95% CI=.3, .8) There were no significant associations with the percentage of Black residents, median household income, or the percentage of population under age 18 (Table 3, Models 7–8).

Conclusion

This is the first study to comprehensively examine retail marketing and promotions for cigarettes and other tobacco products by neighborhood characteristics in a representative sample of tobacco retailers in the contiguous US. Retail tobacco marketing was omnipresent. Stores featured nearly 30 tobacco product marketing materials on average, 75.1% featured one or more price promotions, and 81.3% sold flavored cigars. Stores in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of non-Hispanic Black residents were more likely to feature a price promotion or sell flavored cigars. Price promotions were also more common in stores located in neighborhoods with a greater proportion of youth. Taken together, these findings suggest that tobacco products, along with their advertising and promotions, are widely available in stores across the country and that tobacco companies appear to be targeting their products, including candy and fruit flavored products, by offering price promotions in neighborhoods with more youth and non-Hispanic Black residents.

A greater presence of tobacco marketing in Black/African American neighborhoods has been found in other studies25,35 and systematic reviews.20,36 Of these, the study most similar to ours documented a 9% increase in the number of marketing materials for every 10 percentage point increase in the proportion of a store neighborhood that is Black/African American in Minneapolis.35 Based on our regression model we find that on average, stores in quartiles 3 or 4 (>4.96% non-Hispanic Black) have 10–30% more marketing materials than stores in quartile 1 (<1% non-Hispanic Black).

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to find more price promotions in neighborhoods with more children. Studies in California25 and New York37 found that stores in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of youth had more price promotions for menthol cigarettes. Our results suggest that the presence of price promotions for any tobacco product increased with the proportion of youth in the store neighborhood. We also found that products that appeal to youth are particularly prevalent in the types of stores that youth visit most frequently.34 Flavored cigars, in particular, were available in more than 80% of gas stations, convenience stores and pharmacies. Nearly half of all adolescents visit convenience stores at least once a week, and the odds of visiting are nearly double for African-American youth.34 The patterns of marketing and product availability are troubling given that point of sale tobacco marketing is related to increased youth initiation and tobacco use.10,11,38

Similar to other studies,24,35 we find no association between the proportion of Hispanic residents and any measures of marketing or product availability, with the exception of smokeless products, which were less likely to be available in the most heavily Hispanic areas. Perhaps the industry does not explicitly target Hispanic populations because they smoke at lower rates than other ethnic groups, or perhaps stores (e.g., tiendas) in Hispanic neighborhoods are smaller and less likely to feature marketing, have large tobacco product assortments, or offer price promotions. We also did not find differences between neighborhood income levels and measures of marketing or product availability. Lower levels of neighborhood income in both Omaha, Nebraska and Ontario, Canada were associated with more tobacco marketing materials and promotions,22,24 but in Minneapolis, larger proportions of the population using public assistance or living below 150% of the poverty level was only associated with menthol advertising, and not with overall number of marketing materials.35 Evidence that the amount of marketing materials, price promotions, and flavored products were related to several store neighborhood characteristics emphasizes the utility and importance of store environment assessments.

Our findings suggest that additional policies are needed to counteract this unhealthy retail environment, particularly for youth and for African American residents. The widespread availability of flavored cigars and single cigars should be addressed. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA)39 banned flavored cigarettes, but the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not ban flavors in cigars as part of their “deeming” rules. This would be important for a future regulation as African Americans smoke cigars at higher rates than whites.40,41 Local jurisdictions are implementing flavor restrictions and minimum pack size restrictions42 and these efforts should accelerate in the absence of federal rules. Given that the FDA flavored cigarette ban appears to have contributed to lower youth tobacco use,43 communities may want to enact bans on other flavored products.

Tobacco product price promotions are particularly appealing to youth44 and to low-income tobacco users.45 The tobacco industry significantly increased its use of price promotions after the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement.46 Jurisdictions, such as Providence, RI, and New York City, NY have banned tobacco industry price promotions including coupon redemption, special price discounts, and buy one get one free specials.47 These restricitions on price promotions appear to be on solid legal grounding based on recent court decisions, although comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising are unconstitutional.42 Similar restrictions should be implemented at other local, state, and federal levels. In spite of the large quantity of tobacco marketing materials in stores, policies to restrict advertising are less likely to survive legal challenges than policies to restrict sales, such as banning a type of product (e.g., menthol cigarettes), or regulating the manner (e.g., self-service displays) and location (e.g., prohibiting sales in pharmacies and near schools) of sale.42

Study strengths include a large representative sample of US stores, making this one of the few national studies of point-of-sale marketing. The current study used best practices for store audit data collection,28 included multiple tobacco products, and focused on youth appeal. A limitation is that we did not measure the size or prominence of marketing materials. Although the data collection protocol was standardized, these two measures had low reliability, making it more difficult to detect associations with store type and neighborhood demographics.28 The exclusion of Alaska and Hawaii from our sample due to the impracticably high cost of data collection in either place limits the generalizability of our sample to the contiguous United States. We also lumped all types of cigars together for parsimony, however, the use patterns of cigarillos vary from big cigars.

Future studies should identify the impact of programs and policies to curtail targeted marketing of tobacco products to vulnerable populations. The tobacco industry has a long history of targeting youth, racial/ethnic populations, and low-income individuals, and these practices continue. Given that most tobacco control interventions do little to reduce or eliminate disparities in tobacco use,48 finding such policy levers is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mike Bowling for his assistance in developing the sampling plan for this study.

Funding/Support: Funding for this study was provided by grant number U01 CA154281 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute as part of the State and Community Tobacco Control Initiative. The funders had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, writing, or interpretation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Ribisl has served as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers and Internet tobacco vendors. Dr. Ribisl and Ms. Feld have a royalty interest in a mobile store observation system owned by UNC-Chapel Hill. This system is not described or mentioned in this paper.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report - United States, 2013. MMWR. 2013;62(Suppl 3):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu SS, Neff L, Agaku IT, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(27):685–691. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6527a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students--United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Apelberg BJ, King BA. Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students--United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1066–1070. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6438a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Services USDoHaH. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2014. Washington D.C: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2014. Washington D.C: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Trends in exposure to pro-tobacco advertisements over the Internet, in newspapers/magazines, and at retail stores among U.S. middle and high school students, 2000–2012. Prev Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim AE, Loomis BR, Busey AH, Farrelly MC, Willett JG, Juster HR. Influence of retail cigarette advertising, price promotions, and retailer compliance on youth smoking-related attitudes and behaviors. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(6):E1–E9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182980c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y, et al. The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):315–320. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu X, Pesko MF, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB, Malarcher AM, Pechacek TF. Cigarette price-minimization strategies by US smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(5):472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi K, Hennrikus DJ, Forster JL, Moilanen M. Receipt and redemption of cigarette coupons, perceptions of cigarette companies and smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):418–422. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, Claire AWS. Use of price-minimizing strategies by smokers and their effects on subsequent smoking behaviors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;14(7):864–870. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O’Connor RJ, et al. How do price minimizing behaviors impact smoking cessation? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(5):1671–1691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. R. J. Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry CL. The tobacco industry and underage youth smoking: tobacco industry documents from the Minnesota litigation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(9):935–941. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):377–384. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JG, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russel S, Ribisl KM. A Systematic Review of Neighborhood Disparities in Point-of-Sale Tobacco Marketing. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreland-Russell S, Harris J, Snider D, Walsh H, Cyr J, Barnoya J. Disparities and menthol marketing: additional evidence in support of point of sale policies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(10):4571–4583. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.John R, Cheney MK, Azad MR. Point-of-sale marketing of tobacco products: taking advantage of the socially disadvantaged? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(2):489–506. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laws MB, Whitman J, Bowser DM, Krech L. Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing in demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 2):ii71–73. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siahpush M, Jones PR, Singh GK, Timsina LR, Martin J. The association of tobacco marketing with median income and racial/ethnic characteristics of neighbourhoods in Omaha, Nebraska. Tobacco control. 2010;19(3):256–258. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted advertising, promotion, and price for menthol cigarettes in California high school neighborhoods. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):116–121. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cowling DW, Kline RS, Fortmann SP. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Preventive medicine. 2008;47(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantrell J, Kreslake JM, Ganz O, et al. Marketing little cigars and cigarillos: advertising, price, and associations with neighborhood demographics. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1902–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JG, Henriksen L, Myers AE, Dauphinee AL, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of store audit methods for assessing tobacco marketing and products at the point of sale. Tob Control. 2014;23(2):98–106. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chromy JR. Sequential sample selection methods. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the American statistical association, survey research methods section; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Angelo H, Fleischhacker S, Rose SW, Ribisl KM. Field validation of secondary data sources for enumerating retail tobacco outlets in a state without tobacco outlet licensing. Health Place. 2014;28:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Census Bureau. Economic Census; generated by H. D’Angelo; using American Factfinder hfcgN. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.HLM 7.00 for Windows [Computer software] [computer program] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290–297. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders-Jackson A, Parikh NM, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Convenience store visits by US adolescents: Rationale for healthier retail environments. Health Place. 2015;34:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Widome R, Brock B, Noble P, Forster JL. The relationship of neighborhood demographic characteristics to point-of-sale tobacco advertising and marketing. Ethnicity & health. 2013;18(2):136–151. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.701273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Primack BA, Bost JE, Land SR, Fine MJ. Volume of tobacco advertising in African American markets: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(5):607–615. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waddell EN, Sacks R, Farley SM, Johns M. Point-of-Sale Tobacco Marketing to Youth in New York State. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(3):365–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion on Smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribisl KM. Research gaps related to tobacco product marketing and sales in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):43–53. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobacco product use among middle and high school students--United States, 2011 and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(45):893–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al. Tobacco product use among adults--United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lange T, Hoefges M, Ribisl KM. Regulating Tobacco Product Advertising and Promotions in the Retail Environment: A Roadmap for States and Localities. J Law Med Ethics. 2015;43(4):878–896. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courtemanche CJ, Palmer MK, Pesko MF. Influence of the Flavored Cigarette Ban on Adolescent Tobacco Use. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierce JP, Gilmer TP, Lee L, Gilpin EA, de Beyer J, Messer K. Tobacco industry price-subsidizing promotions may overcome the downward pressure of higher prices on initiation of regular smoking. Health Econ. 2005;14(10):1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/hec.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornelius ME, Driezen P, Hyland A, Fong GT, Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM. Trends in cigarette pricing and purchasing patterns in a sample of US smokers: findings from the ITC US Surveys (2002–2011) Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl 3):iii4–iii10. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loomis BR, Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker JM, Mann NH. Point of purchase cigarette promotions before and after the Master Settlement Agreement: exploring retail scanner data. Tob Control. 2006;15(2):140–142. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLaughlin I, Pearson A, Laird-Metke E, Ribisl K. Reducing tobacco use and access through strengthened minimum price laws. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1844–1850. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]