Abstract

Objective

This study examined the effect of adjunctive telmisartan on psychopathology and cognition in olanzapine or clozapine treated patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

In a 12-week randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study, patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder received either telmisartan (80mg once per day) or placebo. Psychopathology was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), and a neuropsychological battery was used to assess cognitive performance. Assessments for psychopathology and cognition were conducted at baseline and week 12.

Results

Fifty-four subjects were randomized and 43 completed the study (22 in the telmisartan group, 21 in the placebo group). After 12-weeks of treatment, the telmisartan group had a significant decrease in PANSS total score compared to the placebo group (mean ± SD: −4.1 ± 8.1 versus 0.4 ± 7.5, p=0.038, Cohen’s d=0.57). There were no significant differences between the two groups in change from baseline to week 12 in PANSS subscale scores, SANS total score or any cognitive measures (p’s > 0.100).

Conclusion

The present study suggests that adjunctive treatment with telmisartan may improve schizophrenia symptoms. Future trials with larger sample sizes and longer treatment durations are warranted.

Keywords: schizophrenia, psychopathology, cognition, psychopharmacology

Introduction

Immune dysfunction and inflammation have been well-described in patients with schizophrenia (1, 2). Previous research has attempted to identify specific inflammatory markers in relation to schizophrenia. For example, both Naudin et al. (3) and Lin et al. (4) found that, compared with healthy controls, patients with chronic schizophrenia had significantly higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Several studies have suggested that the regulation of inflammatory and immunological processes may be related to the manifestation of symptoms and treatment response in schizophrenia. Our group previously reported that higher blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) or white blood cell count (WBC) were associated with a worse psychopathology profile in patients with schizophrenia (5, 6). Others found that higher baseline levels of cerebrospinal fluid pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) were associated with worsening psychotic symptoms during haloperidol withdrawal (7), while lower baseline serum levels of IL-2 were associated with greater improvement in clinical symptoms in schizophrenia patients treated with haloperidol or risperidone (8). Researchers have also examined the potential benefit of anti-inflammatory agents in treating schizophrenia (9). For example, celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) anti-inflammatory agent, when added to risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, significantly reduced psychopathology as measured by the PANSS total score (10). Another study found that aspirin given as adjuvant therapy to regular antipsychotic treatment reduced the symptoms of schizophrenia (11).

Patients with schizophrenia suffer from cognitive deficits especially in the domains of attention, verbal memory, and executive function (12). An accumulating body of evidence now suggests that the severity of cognitive impairments is highly correlated with the real life functioning in patients with schizophrenia (13). Studies have suggested that inflammation may play an important role in the development of cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia (14). Therefore, it is of great interest to explore the potential cognitive benefit of those agents with anti-inflammatory property in this patient population.

Telmisartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker (ARB), is approved for the treatment of hypertension alone or in combination with other antihypertensive agents. Pro-inflammatory properties of angiotensin II as well as anti-inflammatory effects of are well-established (15–17). For example, animal studies have demonstrated that peripherally administered ARBs can prevent or reverse the inflammatory process associated with brain ischemia and stroke (18, 19). In addition, telmisartan has been found to increase serum concentrations of adiponectin and reduce concentrations of high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) (20, 21) ; both of these effects are associated with protection from diabetes and atherosclerosis.

The discovery of angiotensin II receptors in the brain confirmed the existence of a brain angiotensin II system, which responds to angiotensin II generated in and transported into the brain (22). In rats, following peripheral administration, telmisartan can penetrate the blood-brain barrier in a dose- and time-dependent manner to inhibit centrally mediated effects of angiotensin II (23). Animal studies with peripherally administered ARBs have suggested that angiotensin II is involved in the modulation of cerebral blood flow, brain development, neuronal migration, processing of sensory information, cognition, and regulation of emotional response (24).

Aims of the study

We conducted a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of telmisartan 80 mg/day as an adjunctive therapy in clozapine or olanzapine treated schizophrenia patients. The effects of adjunctive telmisartan treatment on body weight and metabolism, the primary outcomes of the study, were reported separately (under review). The aims of this study were to:

Examine the effects of telmisartan on psychopathology and cognition after 12-week telmisartan treatment.

Examine the role of telmisartan’s anti-inflammatory property in possible changes in clinical symptoms.

Methods

Participants

Adult outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were recruited from an urban community-based general mental health clinic in Boston, Massachusetts. Psychiatric diagnosis was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (25). Other inclusion criteria included: 1) age 18 to 65 years; 2) treatment with clozapine or olanzapine for at least 6 months; 3) stable dose of the current antipsychotic drug for at least 1 month; 4) English speaking and able to complete the cognitive assessment. Exclusion criteria were: 1) inability to provide informed consent; 2) current substance use; 3) unstable medical conditions; 4) current insulin treatment for diabetes; 5) history of immunosuppression; 6) current or recent radiation or chemotherapy for cancer; 7) chronic use of steroids; 8) pregnancy or breastfeeding; 9) use of diuretics, ACE inhibitors, spironolactone, potassium supplements, digoxin or warfarin because of possible drug-drug interactions with telmisartan. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, and followed the Good Clinical Practice guideline. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT00981526).

Procedure

At baseline, eligible subjects completed an assessment which included the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (26), the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (27), the Calgary Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) (28), the Heinrichs Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (29), and the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE) (30). The SAFTEE assesses 23 categories of possible drug side effects organized according to organ system or body region, with a total of 78 specific queries. Cognition assessment included: 1) The Verbal Fluency Test is to measure executive function. 2) The Trail Making Test is to measure psychomotor speed and mental set shifting. In Trails A, subjects draw lines connecting circles that are numbered 1 to 25. In Trails B, subjects connect circles by alternating between ascending numbers and letters in alphabetical order. 3) The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) is to measure verbal memory. 4) The Continuous Performance Test – Identical Pairs (CPT – IP) is to measure focused, sustained attention within a rapidly paced visual vigilance task. This is a computer generated timed test. Subjects are asked to respond as quickly as possible by pressing a key whenever 2 stimuli in a row are identical.

Follow up assessment

Subjects met with the research team every 2 weeks. Each visit included the assessment of vital signs and side effects. Study medication was dispensed during each visit. Subjects were asked to return their bottle of medication during each follow up visit; the quantity of extra study medication in the bottle was recorded to assess adherence. At week 12, the clinical rating scales and cognitive tests were repeated.

Study medication

After screening, subjects were randomized to either telmisartan or placebo in a double blind fashion based on a permuted block design with block size of 6. Subjects took 1 tablet per day (40 mg telmisartan or placebo) for the first 2 weeks, and then took 2 tablets per day (80 mg telmisartan or placebo) for the next 10 weeks. Clinically, the usual starting dose is 40mg once per day, and the maintenance dose is between 40–80mg once per day for hypertension treatment.

Assays for inflammatory markers

Fasting blood samples for inflammatory markers including high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and IL-6 were obtained at baseline and week 12. Laboratory assays were performed by the MGH GCRC Core Lab. Plasma levels of IL-6 were measured by a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Serum levels of hsCRP were measured via a high-sensitivity latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay on a BN II analyzer (Dade Behring, Newark, Del).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 24.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample. Group comparisons were performed using the independent t test for continuous variables, and the Fisher exact test or Chi-square test for categorical variables. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare change scores from baseline to week 12 between the two treatment groups controlling for baseline scores and potential confounding variables. Partial correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between variables of interest controlling for potential confounding variables. For all analyses, a p value less than 0.05 (2-tailed) was used for statistical significance. As the purpose of this proof of concept, pilot trial was more explanatory (i.e., identifying the effect of treatment) rather than pragmatic (i.e., identifying the utility of treatment for clinical practice), the statistical analysis was primarily focused on those participants who completed the study (completers), followed by ITT analysis with last observation carried forward (LOCF).

Results

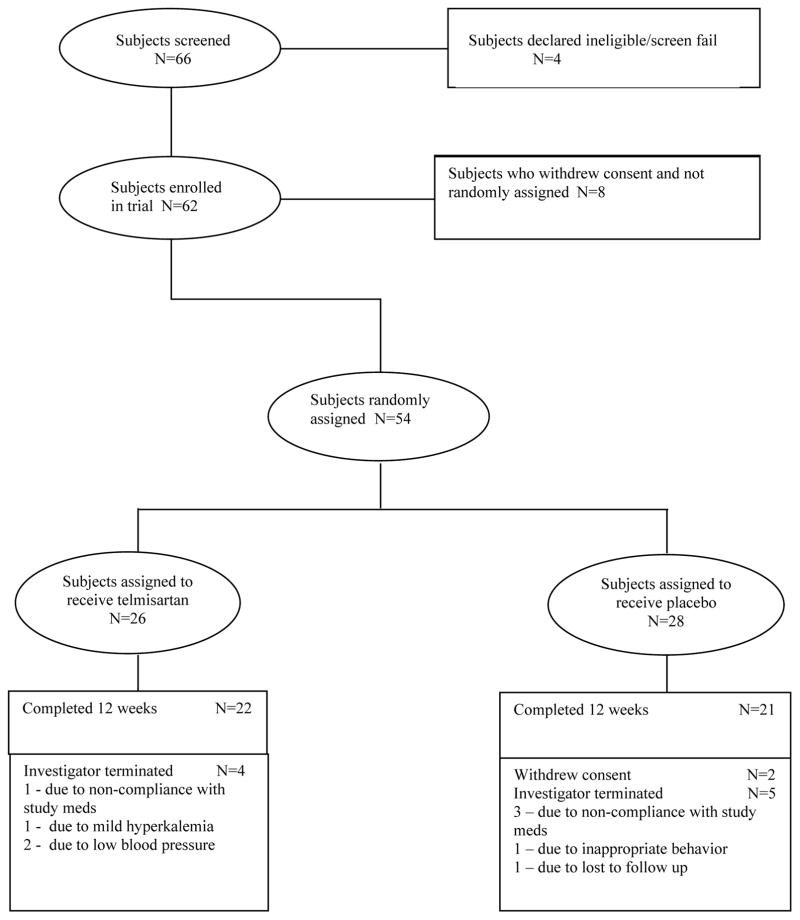

Sixty-six subjects were screened. Among those, 62 were enrolled and 54 were randomized (26 in the telmisartan group, 28 in the placebo group). Forty-three patients completed the study (22 in the telmisartan group, 21 in the placebo group), and were included in the final data analysis (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, gender, race, marital status, diagnosis (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder), clozapine or olanzapine treatment (p’s > 0.300). The telmisartan group tended to have more tobacco users than the placebo group (p = 0.091), lower education level (p = 0.149) and earlier age of illness onset (p = 0.142) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Chart flow for the study sample

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample

| Variable | Telmisartan (N=22) | Placebo (N=21) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

|

|||||

| Age (years) | 41.5 | 12.3 | 44.4 | 11.5 | 0.417 |

| Education (years) | 11.9 | 2.3 | 13.0 | 2.3 | 0.149 |

| Age of illness onset (years) | 20.5 | 5.2 | 23.0 | 5.7 | 0.142 |

| N | % | N | % | ||

|

|

|||||

| Gender | 0.650 | ||||

| Male | 18 | 82 | 16 | 76 | |

| Female | 4 | 18 | 5 | 24 | |

| Race | 0.500 | ||||

| Caucasian | 15 | 68 | 17 | 81 | |

| African American | 5 | 23 | 2 | 10 | |

| Other | 2 | 9 | 2 | 10 | |

| Marital status | 0.395 | ||||

| Single | 20 | 91 | 20 | 95 | |

| Married | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Separated | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Diagnosis | 0.739 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 9 | 41 | 11 | 52 | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 13 | 59 | 10 | 47 | |

| Tobacco use | 0.091 | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 59 | 7 | 33 | |

| No | 9 | 41 | 14 | 67 | |

| Clozapine | 0.835 | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 64 | 14 | 67 | |

| No | 8 | 36 | 7 | 33 | |

| Olanzapine | 0.907 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 36 | 8 | 38 | |

| No | 14 | 64 | 13 | 62 | |

Note: The total percentages may not equal to 100% because of rounding.

Psychopathology and cognition outcome measures

ANCOVA analysis controlling for baseline value, tobacco use, education level, age of illness onset showed a significantly greater decrease from baseline in the PANSS total score at week 12 in the telmisartan group compared to the control group (p=0.038, Cohen’s d=0.57). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in week 12 changes on PANSS subscale scores (Positive Symptoms: p=0.105, d=0.39; Negative Symptoms: p=0.242, d=0.18; General Psychopathology: p=0.100, d=0.53), or SANS total score (p=0.295, d=0.32). Further, there were no significant differences between the two groups in week 12 changes on QLS total score, or any cognitive measures (CPT d prime, hits rate, reaction time of hits, false-alarm rate, HVLT- immediate recall and delayed recall, verbal fluency, Trails A and B) (p’s > 0.200, Table 2).

Table 2.

Psychopathology and cognition outcome measures after 12-week treatment

| Variable | Telmisartan (N=22) | Placebo (N=21) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 12 change Mean (SD) |

Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 12 change Mean (SD) |

||

| PANSS total | 71.2 (12.1) | −4.1 (8.1) | 70.5 (20.4) | 0.4 (7.5) | 0.038 |

| PANSS Positive | 16.7 (5.5) | −1.2 (2.5) | 16.4 (7.6) | −0.1 (3.1) | 0.105 |

| PANSS Negative | 19.9 (6.5) | −0.4 (2.9) | 20.0 (5.5) | 0.1 (2.8) | 0.242 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology | 34.6 (6.8) | −2.4 (5.4) | 34.1 (10.0) | 0.3 (4.7) | 0.100 |

| SANS total | 33.1 (13.2) | −2.2 (6.5) | 33.4 (13.3) | −0.3 (5.5) | 0.295 |

| QLS total | 69.7 (13.8) | 0.5 (6.4) | 72.2 (19.9) | −1.1 (4.4) | 0.586 |

| CPT d prime | 1.97 (0.91) | 0.06 (0.44) | 2.28 (0.77) | 0.15 (0.39) | 0.350 |

| CPT hits rate, % | 0.70 (0.18) | 0.00 (0.10) | 0.77 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.256 |

| CPT reaction time of hits, milliseconds | 557.3 (74.9) | −2.5 (49.5) | 547.2 (75.0) | −16.1 (46.2) | 0.631 |

| CPT false-alarm rate, % | 0.13 (0.10) | −0.01 (0.06) | 0.13 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.497 |

| HVLT immediate recall total | 19.8 (6.7) | 2.0 (4.0) | 20.8 (7.5) | 1.9 (3.4) | 0.680 |

| HVLT delayed recall | 6.1 (3.3) | 0.9 (1.6) | 6.0 (3.3) | 1.5 (1.7) | 0.552 |

| Verbal fluency total | 28.1 (11.0) | 1.8 (4.1) | 34.1 (14.9) | 0.6 (5.9) | 0.830 |

| Trails A, seconds | 42.5 (13.7) | −2.8 (9.5) | 40.3 (20.6) | −5.3 (9.9) | 0.277 |

| Trails B, seconds | 119.6 (54.7) | −7.6 (31.8) | 138.1 (85.8) | −7.0 (66.6) | 0.687 |

Notes: 1) Week 12 change equals week 12 value minus baseline value; 2) PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; 3) SANS, the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; 4) QLS, the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale; 5) CPT, the Continuous Performance Test; 6) HVLT, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; 7) p values were based on ANCOVA comparing between group differences in week 12 changes controlling for baseline values, age of illness onset, education and tobacco use.

Inflammatory markers

ANCOVA analysis controlling for baseline value, tobacco use, education level, age of illness onset showed that the telmisartan group had a significant decrease from baseline in plasma levels of IL-6 at week 12 compared to the control group (−1.49 ± 4.07 pg/mL versus 0.71 ± 2.49 pg/mL, p = 0.019, d=0.65) (mean ± SD). However, there were no significant difference between the two groups in week 12 change in serum levels of hsCRP (−0.49 ± 3.42 mg/L versus −0.35 ± 2.67 mg/L, p = 0.866, d=0.05). Partial correlation analysis found no significant relationships between the change in plasma levels of IL-6 and changes in PANSS total or subscale scores, SANS total score, QLS total score or any cognitive measures (p’s > 0.100).

Side effect assessment

There were no serious adverse events during the study. For all randomized subjects (N=54), the side effects reported in more than 5% of the subjects taking telmisartan were diarrhea, fatigue/tiredness, dizziness/faintness, sore throat, nasal congestion, lightheadedness, and chest pain (Table 3). There were no significant differences between the two groups for listed side effects except dizziness/faintness (23% in the telmisartan group versus 4% in the control group, p=0.047). Three subjects in the telmisartan group and none in the placebo group discontinued from the study because of a significant decrease in systolic, diastolic, or orthostatic blood pressure.

Table 3.

Side effect assessment for all randomized subjects (N=54)*

| Adverse event | Telmisartan (N=26) | Placebo (N=28) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Diarrhea | 3 | 12 | 2 | 7 | 0.663 |

| Fatigue/tiredness | 4 | 15 | 3 | 11 | 0.699 |

| Dizziness/faintness | 6 | 23 | 1 | 4 | 0.047 |

| Sore throat | 2 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0.604 |

| Nasal congestion | 2 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 1.000 |

| Lightheadedness | 3 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 0.342 |

| Chest pain | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0.105 |

Occurred in more than 5% of the subjects taking telmisartan

The ITT analysis with LOCF

The analysis was repeated in the ITT population with LOCF. There were no significant differences between the two groups in demographic or general clinical characteristics (p’s > 0.200). ANCOVA analysis controlling for baseline value showed a significantly greater decrease from baseline in the PANSS total score at week 12 in the telmisartan group compared to the control group (−3.7 ± 8.5 versus 0.7 ± 8.1, p=0.041, Cohen’s d=0.53). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in week 12 changes on PANSS subscale scores (p’s > 0.200). In addition, there were no significant differences between the two groups in week 12 changes on QLS total score, or any cognitive measures (CPT d prime, hits rate, reaction time of hits, false-alarm rate, HVLT- immediate recall and delayed recall, verbal fluency, Trails A and B) (p’s > 0.200). Further, there were no significant differences between the two groups in week 12 changes in serum levels of IL-6 or hsCRP (p’s > 0.200).

Discussion

We believe that this study represents the first double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial to examine the impact of adjunctive telmisartan therapy on psychopathology and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or clozapine. The 12-week study showed that telmisartan treatment had a beneficial effect on psychopathology as reflected by a significant decrease in PANSS total score. About two thirds of the study participants were taking clozapine, which suggests that the majority of subjects in the study did not respond well to other antipsychotic agents. The suggested benefit of telmisartan to improve schizophrenia symptoms in a group of relatively treatment refractory patients is encouraging.

Both animal and human studies have shown that ARBs ameliorate inflammatory conditions and reduce oxidative stress (31). Our study showed that 12-week telmisartan treatment significantly decreased plasma levels of IL-6. This finding is consistent with the report based on a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of telmisartan therapy in the general population (32). ARBs, telmisartan in particular, penetrate the brain parenchyma when administered systemically (33). Telmisartan may improve schizophrenia symptoms by its anti-inflammatory effect on the brain even though our study failed to show a significant relationship between the week 12 change in IL-6 and the week 12 changes in psychopathology measures.

A recent animal study reported that telmisartan attenuates cognitive impairment caused by chronic stress in rats (34). Studies have also reported that ARBs protect against cognitive deterioration in patients with mild cognitive impairment (35), and may delay the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (36). It has been proposed that telmisartan may exert its cognitive benefit via up-regulation of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and inhibition of neuro-inflammation and oxidative-nitrosative stress (37). Our study failed to demonstrate cognitive benefit of 12-week adjunctive telmisartan therapy in olanzapine or clozapine treated patients with schizophrenia. Benefits mediated via neurotrophic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms may require a longer treatment duration than the 12-week period of the current trial.

In our study, more patients experienced dizziness and faintness in the telmisartan group than in the control group, which was likely related to the blood pressure lowering effect of telmisartan. As blood pressure response to telmisartan is dose related over the range 10–80mg (38), future studies may consider flexible dosing of telmisartan to minimize possible side effects of dizziness and faintness.

There are several limitations in the present study. As this was an exploratory trial, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. The small sample size prevents meaningful subgroup analysis for those patients receiving olanzapine or clozapine monotherapy; it is unclear whether or not telmisartan may have differential effects on psychopathology and cognition for olanzapine versus clozapine treated patients. In addition, it is unclear if the findings from this study are generalizable to those patients taking antipsychotic agents other than olanzapine or clozapine. Another limitation is the relatively short intervention (12 weeks).

Future trials with larger sample sizes and longer durations of treatment are needed to better understand the effects of adjunctive telmisartan therapy on psychopathology, cognition, and safety in patients with schizophrenia, and to identify biomarkers or subgroups of patients that might predict treatment response. Further, it will be of great interest to examine the potential benefit of telmisartan in individuals in the prodrome phase or with first episode psychosis.

Significant outcomes

Telmisartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, improved clinical symptoms in patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or clozapine.

The therapeutic effect of telmisartan might be related to its anti-inflammatory property.

Limitations

The small sample size prevents meaningful subgroup analysis for those patients receiving olanzapine or clozapine monotherapy.

It is unclear if the findings from this study are generalizable to those patients taking antipsychotic agents other than olanzapine or clozapine.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosures

Dr. Fan has received research support or honoraria from Allergen, Janssen, Alkermes, Avanir, Neurocrine, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Jarskog has received research support from Auspex/Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Otsuka. Dr. Freudenreich has received research support or honoraria from Avanir, Neurocrine, and Janssen. Dr. Goff has received research support from Avanir. Dr. Henderson has received research support from Otsuka. Drs. Song, Natarajan, and Shukair report no competing interests.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00981526

Funding sources

This study was supported by Grant 5K23MH082098 from the National Institutes of Health (Dr. Fan), the NARSAD Young Investigator Award (Dr. Fan).

References

- 1.Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girgis RR, Kumar SS, Brown AS. The cytokine model of schizophrenia: emerging therapeutic strategies. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naudin J, Capo C, Giusano B, Mege JL, Azorin JM. A differential role for interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1997;26(2–3):227–33. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin A, Kenis G, Bignotti S, Tura GJ, De Jong R, Bosmans E, et al. The inflammatory response system in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: increased serum interleukin-6. Schizophr Res. 1998;32(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan X, Pristach C, Liu EY, Freudenreich O, Henderson DC, Goff DC. Elevated serum levels of C-reactive protein are associated with more severe psychopathology in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149(1–3):267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan X, Liu EY, Freudenreich O, Park JH, Liu D, Wang J, et al. Higher white blood cell counts are associated with an increased risk for metabolic syndrome and more severe psychopathology in non-diabetic patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1–3):211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAllister CG, van Kammen DP, Rehn TJ, Miller AL, Gurklis J, Kelley ME, et al. Increases in CSF levels of interleukin-2 in schizophrenia: effects of recurrence of psychosis and medication status. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1291–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang XY, Zhou DF, Cao LY, Zhang PY, Wu GY, Shen YC. Changes in serum interleukin-2, -6, and -8 levels before and during treatment with risperidone and haloperidol: relationship to outcome in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):940–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommer IE, van Westrhenen R, Begemann MJ, de Witte LD, Leucht S, Kahn RS. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory agents to improve symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):181–91. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller N, Riedel M, Scheppach C, Brandstatter B, Sokullu S, Krampe K, et al. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of celecoxib add-on therapy compared to risperidone alone in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):1029–34. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laan W, Grobbee DE, Selten JP, Heijnen CJ, Kahn RS, Burger H. Adjuvant aspirin therapy reduces symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):520–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05117yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004;72(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misiak B, Stanczykiewicz B, Kotowicz K, Rybakowski JK, Samochowiec J, Frydecka D. Cytokines and C-reactive protein alterations with respect to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II Cell Signaling: Physiological and Pathological Effects in the Cardiovascular System. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;26:26. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navalkar S, Parthasarathy S, Santanam N, Khan BV. Irbesartan, an angiotensin type 1 receptor inhibitor, regulates markers of inflammation in patients with premature atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):440–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda T, Hoshida S, Nishino M, Tanouchi J, Otsu K, Hori M. Relationship between effects of statins, aspirin and angiotensin II modulators on high-sensitive C-reactive protein levels. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169(1):155–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando H, Jezova M, Zhou J, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade decreases brain artery inflammation in a stress-prone rat strain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:345–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito T, Yamakawa H, Bregonzio C, Terron JA, Falcon-Neri A, Saavedra JM. Protection against ischemia and improvement of cerebral blood flow in genetically hypertensive rats by chronic pretreatment with an angiotensin II AT1 antagonist. Stroke. 2002;33(9):2297–303. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000027274.03779.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miura Y, Yamamoto N, Tsunekawa S, Taguchi S, Eguchi Y, Ozaki N, et al. Replacement of valsartan and candesartan by telmisartan in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes: metabolic and antiatherogenic consequences. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):757–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koulouris S, Symeonides P, Triantafyllou K, Ioannidis G, Karabinos I, Katostaras T, et al. Comparison of the effects of ramipril versus telmisartan in reducing serum levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(11):1386–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauser W, Johren O, Saavedra JM. Characterization and distribution of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the mouse brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;348(1):101–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gohlke P, Weiss S, Jansen A, Wienen W, Stangier J, Rascher W, et al. AT1 receptor antagonist telmisartan administered peripherally inhibits central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298(1):62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saavedra JM. Brain angiotensin II: new developments, unanswered questions and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25(3–4):485–512. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-4011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):624–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kay SR, Opler LA, Lindenmayer JP. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): rationale and standardisation. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;(7):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. The British journal of psychiatry Supplement. 1989;(7):49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E, Joyce J. Reliability and validity of a depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophrenia research. 1992;6(3):201–8. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90003-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT., Jr The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388–98. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacology bulletin. 1986;22(2):343–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saavedra JM. Evidence to Consider Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers for the Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(2):259–79. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0327-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takagi H, Mizuno Y, Yamamoto H, Goto SN, Umemoto T. Effects of telmisartan therapy on interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(4):368–73. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda A, Fushiki H, Murakami Y, Sasaki H, Miyoshi S, Kakuta H, et al. Brain penetration of telmisartan, a unique centrally acting angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, studied by PET in conscious rhesus macaques. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39(8):1232–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wincewicz D, Braszko JJ. Telmisartan attenuates cognitive impairment caused by chronic stress in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66(3):436–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hajjar I, Hart M, Chen YL, Mack W, Novak V, HCC, et al. Antihypertensive therapy and cerebral hemodynamics in executive mild cognitive impairment: results of a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):194–201. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kume K, Hanyu H, Sakurai H, Takada Y, Onuma T, Iwamoto T. Effects of telmisartan on cognition and regional cerebral blood flow in hypertensive patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2012;12(2):207–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khallaf WA, Messiha B, Abo-Youssef A, El Sayed NS. Protective effects of Telmisartan and tempol on lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment, neuro-inflammation and amyloidogenesis: possible role of brain derived neurotrophic factor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker AB, Azevedo ER, Baird MG, Smith SJ, Arnold JM, Humen DP, et al. ARCTIC: assessment of haemodynamic response in patients with congestive heart failure to telmisartan: a multicentre dose-ranging study in Canada. Am Heart J. 1999;138(5 Pt 1):843–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]