Summary

Background

Previously reported results of phase 2 and phase 3 trials showed a significant improvement in the rate of objective response and progression-free survival with nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) plus ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) vs ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma. To our knowledge, this is the first report of overall survival data from a randomised, controlled trial evaluating the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma.

Methods

In this phase 2 trial (CheckMate 069), 142 patients aged ≥18 years with previously untreated, unresectable stage III or IV melanoma, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive an intravenous infusion of nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg or ipilimumab 3 mg/kg plus placebo, every 3 weeks for 4 doses, followed by nivolumab 3 mg/kg or placebo, respectively, every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Randomisation was done by an interactive voice response system with a permuted block schedule and stratification by BRAF mutation status. The primary endpoint (previously reported) was the rate of investigator-assessed objective response among patients with BRAF V600 wild-type melanoma. Overall survival was an exploratory endpoint. Efficacy analyses were done on the intention-to-treat population, where safety was evaluated in all treated patients. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01927419, and is ongoing but no longer enrolling patients.

Findings

Between September 16, 2013, and February 6, 2014, we screened 179 patients, randomly allocating 95 patients to nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 47 to ipilimumab (72 [76%] and 37 [79%] patients with BRAF V600 wild-type tumors, respectively). At a median follow-up of 24 months, overall survival rates in all randomized patients were 63·8% (95% CI 53·3–72·6) for nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs 53·6% (95% CI 38·1–66·8) for ipilimumab alone; median overall survival had not been reached in either group (hazard ratio 0·74, 95% CI 0·43–1·26; p=0.26). Grade 3–4 adverse events related to nivolumab plus ipilimumab were reported in 51 [54%] of 94 patients vs 9 [20%] of 46 patients related to ipilimumab alone. The most common treatment-related grade 3–4 adverse events in the combination group were colitis (12 [13%] of 94 patients) and increased alanine aminotransferase (10 [11%]), and for ipilimumab alone, were diarrhoea (five [11%] of 46 patients) and hypophysitis (two [4%]). Serious grade 3–4 adverse events related to nivolumab plus ipilimumab were reported in 34 [36%] of 94 patients vs 4 [9%] of 46 patients related to ipilimumab alone, which included colitis (10 [11%]) and diarrhoea (5 [5%]) in the combination group and diarrhoea (2 [4%]), colitis (1 [2%]), and hypophysitis (1[2%]) in the ipilimumab alone group.

Interpretation

While follow-up of the patients continues, the results of this analysis suggest that the combination of first-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab may lead to a higher overall survival rate vs first-line ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma. The results suggest encouraging survival outcomes with immunotherapy in this patient population.

Funding

Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Introduction

Survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma have, historically, been very poor, with a median overall survival of ~8 months and a 5-year survival rate from diagnosis of metastatic disease of ~10%.1 Ipilimumab, which blocks cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, was the first agent to demonstrate an improvement in overall survival in a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial of patients with advanced melanoma.2 In this phase 3 trial, the two-year overall survival rate of ipilimumab-treated patients was 25·3%.3 A pooled analysis of data from 12 clinical trials in advanced melanoma, in which some ipilimumab-treated patients were followed up to 10 years, showed durable long-term overall survival with a 3-year survival rate of 22%.4 Newer immune checkpoint inhibitors, which block the programmed death 1 receptor, include nivolumab and pembrolizumab. In a phase 3 trial (CheckMate 066), nivolumab monotherapy demonstrated an improvement in overall survival vs dacarbazine in treatment-naïve patients with BRAF wild-type tumours.5 Follow-up of patients in this study has shown 2-year overall survival rates of 58% with nivolumab and 27% with dacarbazine.6

Both nivolumab and pembrolizumab monotherapy have demonstrated superior efficacy outcomes compared with ipilimumab alone in phase 3 trials of advanced melanoma.7,8 In a phase 2 trial of treatment-naïve patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma (CheckMate 069), the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in objective response rate and longer progression-free survival compared with ipilimumab alone.9 More recently, the results of a phase 3 trial (CheckMate 067) also showed that nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab leads to longer progression-free survival and a higher objective response rate than is achieved with ipilimumab alone in treatment-naïve patients with advanced melanoma.7 In a phase 1 dose-finding study of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab, patient follow-up has shown a 3-year overall survival rate of 68% in previously treated and untreated patients with advanced melanoma.10 Here we present 2-year overall survival data from the CheckMate 069 trial, which, to our knowledge, is the first report of overall survival for the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab from a randomised, controlled trial in advanced melanoma.

Methods

Study design and patients

In this randomised, controlled, double-blind, phase 2 study, we recruited patients at 19 sites in 2 countries (France, United States). Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older and had histologically confirmed, unresectable stage III or stage IV metastatic melanoma with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, and known BRAFV600 mutation status. Patients were also required to have measurable disease by CT or MRI as per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tunors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) criteria, and to provide tumour tissue adequate for biomarker analyses (assessment of PD-L1). We excluded patients with active brain metastases or leptomeningeal metastases and those with ocular melanoma Patients with mucosal melanoma were allowed to enroll. Patients who had received prior systemic anticancer therapy for unresectable or metastatic melanoma were excluded, but prior adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment for melanoma was permitted (if completed at least 6 weeks prior to the date of first dose), and all related adverse events either returned to baseline or stabilized. BRAFV600 mutation testing was done during the screening period using a US Food and Drug Administration-approved test.

Patients provided consent to participate in this study, including follow-up for survival outcomes, using written informed consent forms. The protocol, amendments, and patient consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee at each study site prior to initiation of the trial.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly allocated 2:1 to either nivolumab plus ipilimumab or ipilimumab alone using an interactive voice response system. Once enrolled in the interactive voice response system, patients that met all eligibility criteria were randomised provided that the following information was provided: (1) patient number, (2) date of birth, and (3) BRAF V600 mutation status. We stratified randomisation by BRAF mutation status (V600 mutation-positive vs V600 wild-type). Randomisation procedures were carried out using permuted blocks within each stratum. The study funder, patients, investigators, and study site staff were blinded to the study drug administered. Each study site assigned an unblinded pharmacist/designee who called the interactive voice response system to obtain the treatment assignment for each patient. During the blinded portion of the study, unblinding of study treatment could occur if the investigator determined it is necessary for immediate medical management of the patient (who must have discontinued study treatment) or upon confirmed disease progression. Upon disease progression and after unblinding, patients in the ipilimumab group had the option to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until further disease progression.

Procedures

In the combination group, nivolumab was administered intravenously at a dose of 1 mg/kg over a period of 60 minutes, once every 3 weeks for four doses. Thirty minutes after the completion of each nivolumab infusion, patients received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg over a period of 90 minutes. After the fourth dose of both agents (induction phase), ipilimumab was discontinued and nivolumab was then administered as a single agent at 3 mg/kg over a period of 60 minutes, once every 2 weeks (maintenance phase). In the ipilimumab alone group, the same dosing schedule was used, except that nivolumab was replaced with matched placebo during both the combination and maintenance portions of the trial. Treatment was continued as long as clinical benefit (as defined by the investigator) was observed, until there were unacceptable side effects, patient request to stop study treatment or withdrawal of consent, pregnancy, or termination of the study by the sponsor Dosing interruptions were allowed for the management of adverse events, but dose reductions were not permitted. Patients who experienced disease progression, and were tolerating study therapy, could be treated beyond progression (with blinding maintained) or have blinded study therapy discontinued. After unblinding, patients in the ipilimumab alone group could receive nivolumab at 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until further disease progression; patients in the combination group were required to discontinue treatment.

Tumour response was assessed by the investigators by CT or MRI according to RECIST v1.1 criteria at the following time points: within 28 days prior to the first dose (baseline), 12 weeks after the first treatment, every 6 weeks thereafter for the first year, then every 12 weeks until disease progression or discontinuation of treatment. Responses required confirmation through a subsequent scan at least 4 weeks later. Safety evaluations were performed in patients who had received at least one dose of study treatment, and the severity of adverse events was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.Safety was evaluated in all patients who received at least one dose of study drug, and an adverse events was considered on-study if it occurred within 30 days after the last dose of study treatment. On-study laboratory assessments (including chemistry and haematology tests) were done within 72 hours prior to each dose during the induction phase; during the nivolumab maintenance phase, laboratory assessments were done within 72 hours prior to the first dose and every alternate dose thereafter. Tumour expression of PD-L1 was assessed in pretreatment samples at a central laboratory with the use of a validated, automated immunohistochemical assay (Bristol-Myers Squibb and Dako), as described.11 In each tumour tissue sample, at least 5% of tumour cells showing cell-surface PD-L1 staining of any intensity in a section containing at least 100 evaluable tumour cells was required to determine PD-L1–positivity.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the rate of confirmed objective response among patients with BRAF V600 wild-type tumours (as assessed by the investigators). Secondary endpoints included investigator-assessed progression-free survival in patients with BRAF wild-type tumours, the objective response rate and progression-free survival among patients with BRAF V600 mutation–positive tumours, and safety. Overall survival was an exploratory endpoint.

Statistical analysis

We planned a sample size of 100 patients with BRAF wild-type tumours randomised 2:1 to the two treatment groups. Given a two-sided alpha of 0.05, this number of patients provided an 87% power to detect a significant difference in objective response rate between the groups, assuming an objective response rate of 40% with the combination and 10% with ipilimumab alone.9 Assuming that 66% of the patients had BRAF wild-type tumours, we planned to randomise approximately 150 patients (50 with BRAF mutation-positive tumours). Analyses in the population with BRAF mutation-positive tumours were intended to be descriptive only and thus were not part of the sample size calculations.9 A hierarchical testing approach was applied to key secondary endpoints after analysis of the primary endpoint: the objective response rate among all randomly assigned patients was tested first, followed by progression-free survival among randomized patients with BRAF wild-type tumours, and then progression-free survival among all randomly assigned patients.

For the primary endpoint, the comparison of investigator-assessed objective response rate between treatment groups was performed using Fisher’s exact test. An associated odds ratio and corresponding two-sided 95% CI were calculated. Time-to-event distributions (i.e., progression-free survival, overall survival, time to response, and duration of response) and rates at fixed timepoints were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methodologies. Hazard ratios and corresponding two-sided 95% CIs were estimated using a stratified Cox proportional hazards model. P values for comparisons between groups were calculated using a two-sided, log-rank test with stratification by BRAF mutation status. Per the statistical analysis plan, each efficacy analysis was adjusted for the baseline stratification factor (BRAF mutation status). Analyses of efficacy endpoints were done on the intention-to-treat population, and safety was evaluated in all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. For overall survival analyses, patients were censored on the date that they received subsequent therapy (including ipilimumab-treated patients who crossed over to receive nivolumab monotherapy per protocol). We did all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA). This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01927419.

Role of the funding source

Data collected by the funder were analysed in collaboration with all authors. The study sponsor funded writing and editorial support. All authors had full access to all the data in the current analyses and the corresponding author (FSH) had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

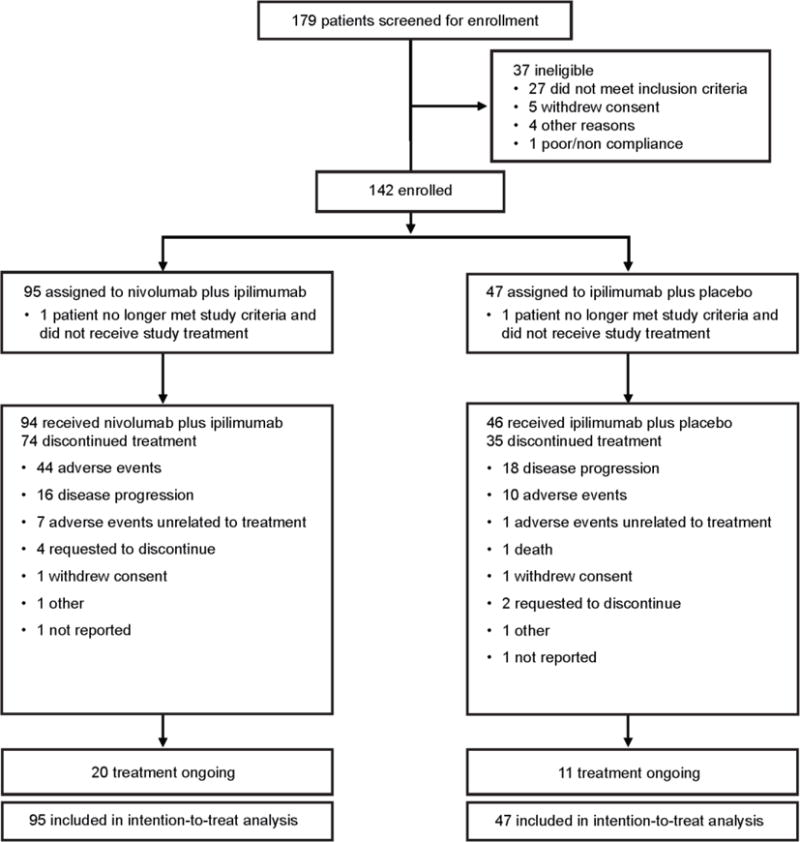

From August 23, 2013, to February 6, 2014, we enrolled 179 patients and randomly allocating 142 (109 with BRAF wild-type tumours and 33 with BRAFV600 mutation-positive tumours) to nivolumab and ipilimumab combination (95 patients) or ipilimumab and placebo (47 patients; figure 1). 72 randomised patients in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group and 37 in the ipilimumab plus placebo group had BRAF wild-type tumours. In each treatment group, one patient no longer met the study criteria following randomisation and thus did not receive study drug. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between both study groups for age, ECOG performance status, M stage, tumour PD-L1 expression ≥5%, and lactate dehydrogenase levels (appendix, p.2).

Figure 1.

Trial profile

At a median follow-up of 24·6 months (IQR 9·7–15·9) for combination therapy and 23·0 months (IQR 9·7–18·7) for ipilimumab (February 29, 2016 database lock), 13 (14%) of 94 patients in the nivolumab and ipilimumab group were continuing treatment vs 6 (13%) of 46 patients in the ipilimumab group; 59 (63%) and 22 (48%) patients, respectively, were continuing with follow-up in the study. The most common reasons for discontinuation of treatment were disease progression (17 [18%] in the combination group vs 19 [41%] in the ipilimumab group) and study drug toxicity (46 [49%] in the combination group vs 10 [22%] in the ipilimumab group). Patients received a median of four doses of nivolumab and ipilimumab in the combination group, with 38 [40%] having received at least one dose of nivolumab maintenance therapy, and a median of four doses of ipilimumab in the ipilimumab alone group. More patients randomised to ipilimumab therapy received subsequent treatment following disease progression (33 [70%] of 47 patients) vs those randomized to combination therapy (33 [35%] of 95 patients) (appendix, p.3). The most common subsequent treatment was anti-PD-1 therapy, in 29 (62%) of 47 patients randomised to ipilimumab (26 received crossover nivolumab per protocol and 3 received nivolumab or pembrolizumab off study) and in 17 (18%) of 95 patients randomised to combination therapy (appendix, p.3). Median time to subsequent therapy was not reached for combination therapy and was 6·1 months (95% CI 4·2–7·4) for ipilimumab.

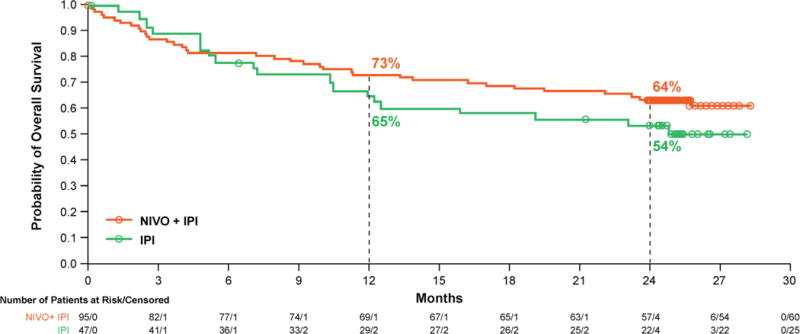

At median follow-up of 2 years, median overall survival in all randomized patients (with and without a BRAF V600 mutation) had not been reached in either group (hazard ratio 0·74; 95% CI 0·43–1·26; p=0.26; figure 2). Overall survival rates at 1 and 2 years were 73·4% (95% CI 63·2–81·2) and 63·8% (95% CI 53·3–72·6) in the combination group and were 64·8% (95% CI 49·1–76·8) and 53·6% (95% CI 38·1–66·8) in the ipilimumab alone group, respectively. A sensitivity analysis for overall survival in patients who received ipilimumab alone, with censoring at the time of crossover, showed similar results (appendix, p.7). We also did a subgroup analysis for overall survival with the combination vs ipilimumab across prespecified subgroups (appendix, p.8). This analysis included patients with BRAF wild-type tumours and those with BRAF mutation-positive tumours (appendix, p.8,10); however, small numbers of patients within these subgroups and the fact that more ipilimumab-treated patients received subsequent therapy (including BRAF or MEK inhibitors) may limit interpretation of these findings.

Figure 2. Overall survival.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival at a median follow-up of 2 years all randomised patients. 35 (37%) of 95 patients experienced an event (death) in the combination group vs 22 (47%) of 47 patients in the ipilimumab group.

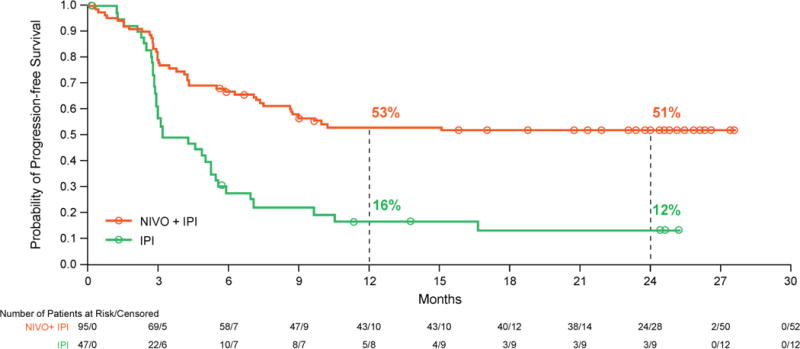

In all randomized patients, median progression-free survival has not been reached for the combination group and was 3·0 months (95% CI 2·7–5·1) in the ipilimumab group (hazard ratio 0·36; 95% CI 0·22–0·56; p<0.0001; figure 3). Progression-free survival rates at 2 years were 51·3% (95% CI 40·4–61·2) in the combination group and 12·0% (95% CI 3·8–25·2) for ipilimumab alone, and appeared to reach a plateau after 12 months. Similar to overall survival, we did a subgroup analysis for progression-free survival with the combination vs ipilimumab across prespecified subgroups (appendix, p.9). Among patients with BRAF mutation-positive tumours, median progression-free survival was 8·5 months (95% CI 2·8–not reached) for the combination group and was 2·7 months (95% CI 1·0–5·4) for ipilimumab alone (hazard ratio 0·38; 95% CI 0·15–1·00, p=0.041; appendix, p.11). Two-year progression-free survival rates were 44·1% (95% CI 22·9–63·4) in the combination group and 12·5% (95% CI 0·7–42·3) for ipilimumab alone.

Figure 3. Progression-free survival.

Kaplan-Meier curves for investigator-assessed disease progression (by RECIST version 1.1) at a median follow-up of 2 years in all randomised patients. 43 (45%) of 95 patients experienced an event (disease progression or death) in the combination group vs 35 (74%) of 47 patients in the ipilimumab group.

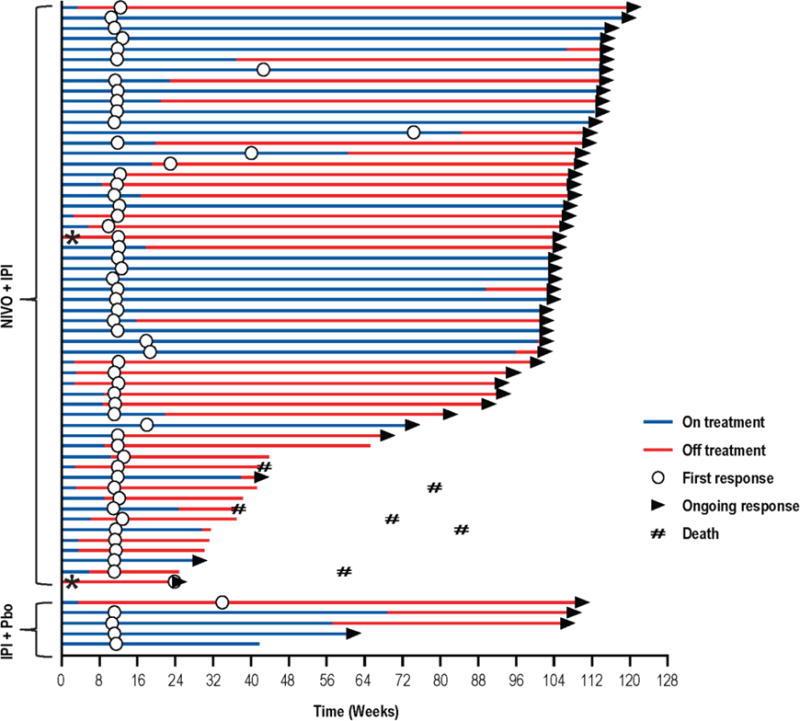

As previously reported,9 the nivolumab and ipilimumab group had a significantly higher response rate than the ipilimumab group (59% vs 11%) in all randomized patients (table 1). Complete responses were reported in 22% of patients in the combination group, and none in the ipilimumab group. Response rates in patients with BRAF mutation-positive tumours were 52% in the combination group vs 10% in the ipilimumab group (table 1).9 In the current analysis, median duration of response was not reached in either group for all randomised patients (table 1). Responses were durable with 45 (80%) of 56 ongoing in the combination group and 4 (80%) of 5 in the ipilimumab group (figure 4). The median change in tumour volume was a 70% reduction in the combination group, compared with a 5% increase in the ipilimumab alone group.

Table 1.

Response to treatment

| All randomized patients | Patients with BRAF wild-type tumours | Patients with BRAF mutation-positive tumours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab and ipilimumab (N=95) |

Ipilimumab (N=47) |

Nivolumab and ipilimumab (N=72) |

Ipilimumab (N=37) |

Nivolumab and ipilimumab (N=23) |

Ipilimumab (N=10) |

|

| Objective response* | 56 (59% [48–69]) | 5 (11% [3–23]) | 44 (61% [49–72]) | 4 (11% [3–25]) | 12 (52% [31–73]) | 1 (10% [0.3–45]) |

| Odds ratio for comparison | 12.2 (4.4–33.7, p<0.0001) | 13.0 (3.9–54.5, p<0.0001) | 9.8 (1.0–465.4) | |||

| Best overall response* | ||||||

| Complete response | 21 (22.1) | 0 | 16 (22.2) | 0 | 5 (21.7) | 0 |

| Partial response | 35 (36.8) | 5 (10.6) | 28 (38.9) | 4 (10.8) | 7 (30.4) | 1 (10.0) |

| Stable disease | 12 (12.6) | 14 (29.8) | 9 (12.5) | 13 (35.1) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Progressive disease | 15 (15.8) | 22 (46.8) | 10 (13.9) | 15 (40.5) | 5 (21.7) | 7 (70.0) |

| Unable to determine | 12 (12.6) | 6 (12.8) | 9 (12.5) | 5 (13.5) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Duration of response | ||||||

| Ongoing responders n/N (%) | 45/56 (80%) | 4/5 (80%) | 35/44 (80%) | 3/4 (75%) | 10/12 (83%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Median (95% CI, months) | NR | NR (6.9–NR) | NR (NR–NR) | NR (6.9–NR) | NR (6.1–NR) | NR |

Based on original database lock. Data are n (% [95% CI]) or n (%). Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

NR=not reached.

Figure 4. Time to and duration of response.

Swimmer plots show time to first response and duration of response, as defined by RECIST version 1.1, for responders who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab (top) or ipilimumab plus placebo (bottom). *Patients received only one dose of combination therapy before discontinuing treatment. Pbo=placebo.

We evaluated efficacy outcomes in the combination group by tumour PD-L1 status, in which 80 (85%) patients had quantifiable PD-L1 expression. No substantive differences in objective response rates were observed between patients with tumour PD-L1 expression ≥5% (58%, 95% CI 37–78) and tumour PD-L1 expression <5% (55%, 95% CI 41–69) (appendix, p.4). Similar results were observed for progression-free and overall survival (appendix, p.5). In all randomized patients who received combination therapy, 2-year overall survival rates were 66·7% (95% CI 44·3–81·7) for PD-L1 expression ≥5% (n=24) and 60·0% (95% CI 45·9–71·5) for PD-L1 expression <5% (n=56). While there were numeric differences in objective response rates, progression-free survival rates, and overall survival rates using a 1% cutoff for tumour PD-L1 expression, there were no statistically significant differences as indicated by overlapping confidence intervals (appendix, p.4,5).

The rates of treatment-related adverse events of any grade were 92% (86 of 94 patients) and 94% (43 of 46 patients) in the combination and ipilimumab alone groups, respectively, at the time of the latest data lock. In the combination and ipilimumab groups, respectively, diarrhea (42 [45%] vs 16 [35%] of patients), rash (40 [43%] vs 14 [30%] of patients), fatigue (34 [36%] vs 22 [48%] of patients) and pruritus (38 [40%] vs 15 [33%] of patients) were the most frequent treatment-related adverse events (table 2). Treatment-related grade 3–4 adverse events continue to be seen more commonly in the combination group than in the ipilimumab group (51 [54%] vs 9 [20%] of patients), and led to treatment discontinuation in 28 (30%) of 94 patients and 4 (9%) of 46 patients, respectively. Serious grade 3–4 adverse events related to nivolumab plus ipilimumab were reported in 34 [36%] of 94 patients vs 4 [9%] of 46 patients related to ipilimumab alone. The most common treatment-related serious grade 3–4 adverse events in the combination group were colitis (10 [11%]) and diarrhoea (5 [5%]), and in the ipilimumab alone group, were diarrhoea (2 [4%]), colitis (1 [2%]), and hypophysitis (1 [2%]). There were no new safety signals in the current analyses.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Nivolumab and ipilimumab (n=94) | Ipilimumab (n=46) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Overall | ||||||||

| Any event | 34 (35) | 41 (44) | 10 (11) | 1 (1)* | 34 (74) | 8 (17) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Adverse events reported in 10% or more of patients | ||||||||

| Rash | 36 (38) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 14 (30) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 37 (39) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 15 (33) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash maculo-papular | 12 (13) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 6 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 33 (35) | 8 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 11 (24) | 4 (9) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Nausea | 19 (20) | 8 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 8 (17) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Colitis | 5 (5) | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (9) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 29 (31) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 22 (48) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 14 (15) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 6 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chills | 11 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase | 19 (20) | 7 (7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 14 (15) | 8 (9) | 2 (2) | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased lipase | 8 (9) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased amylase | 9 (10) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 11 (12) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 16 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypophysitis | 10 (11) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 10 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 11 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 9 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse events leading to discontinuation | ||||||||

| Any event | 6 (6) | 23 (25) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | 0 |

Data are n (%).

Death due to ventricular arrhythmia occurred within the safety reporting period per protocol, ie, up to 30 days after the last dose of study drug. Two other deaths occurred outside of the safety window reporting period: one in a patient who was clinically improving from pneumonitis and had an iatrogenic pneumothorax (69 days after the last treatment) and one in a patient with panhypopituitarism with cortisol deficiency and adrenal crisis (87 days after the last treatment).

A total of 35 (37%) treated patients in the combination group and 22 (48%) in the ipilimumab group had died at the time of the last data cutoff, with 25 of 35 (71%) and 20 of 22 (91%) due to disease progression, respectively. As originally reported, three deaths were attributed by the investigators to treatment-related adverse events in the combination group (none in the ipilimumab group).9 In the current analyses, there have been no additional treatment-related deaths. Select treatment-related adverse events of potential immune-mediated cause occurred more frequently in the nivolumab and ipilimumab group (83 [88%] of 94 patients) than in the ipilimumab alone group (37 [80%] of 46 patients) (appendix, p.6). The most common grade 3–4 treatment-related select adverse events in the combination group were colitis (12 [13%] of 94 patients), increased alanine aminotransferase (10 [11%] of 94 patients), and diarrhea (9 [10%] of 94 patients). Diarrhea was the most commonly reported treatment-related grade 3–4 adverse event in the ipilimumab group (5 [11%] of 46 patients), followed by hypophysitis (2 [4%] of 46 patients).

With the use of immune-modulating agents, the majority (>85%) of grade 3–4 select adverse events resolved in both groups following established algorithms. Time to resolution across all organ categories was typically between 4 and 8 weeks. However, most endocrine events were not considered by the investigators to be resolved, even if well-controlled, due to the requirement for long-term hormone replacement. Among 35 patients who discontinued nivolumab plus ipilimumab treatment at any time due to study drug toxicity, 23 (66%) developed a response, of which 17 (74%) remain in response.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current analysis represents the longest follow-up of patients with advanced melanoma who received the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab in a randomised, controlled trial. At a median follow-up of 2 years, overall survival rates were not statistically different between combination therapy and ipilimumab alone in the all randomised patient population. The results in the overall population were generally consistent across patient subgroups, including those with elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels and M1c disease, although caution is warranted when interpreting these results due to small patient numbers within the subgroups. Note, however, that fewer patients in the current study had elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels and M1c disease compared with other nivolumab trials in advanced melanoma,7 which may have favorably impacted survival outcomes. The interpretation of overall survival differences within the subgroup of patients with BRAF V600 mutation-positive melanoma was limited due to small numbers of patients and the likely effect of crossover to BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment after progression.

A higher than expected 2-year overall survival rate of 53·6% was observed in the ipilimumab group compared to rates previously reported in ipilimumab phase 3 trials (25·3% and 28·9%).3,12 This was likely due to 57% of ipilimumab-treated patients crossing over to receive nivolumab monotherapy while on study, and additional subsequent therapies (not commercially available during the prior ipilimumab phase 3 trials) received by these patients off study. We did not formally characterize the response to subsequent anti-PD-1 therapy after progression on ipilimumab in CheckMate 069, as this has been addressed in other studies in advanced melanoma.13,14 Median progression-free survival was significantly longer in the combination group vs ipilimumab alone for all randomised patients and those with BRAF mutation-positive tumours. Progression-free survival rates were markedly higher in the combination group than in the ipilimumab group, which, in contrast to overall survival rates, would not be impacted by ipilimumab-treated patients crossing over to receive nivolumab or other subsequent therapies.

While the prognosis for patients with advanced melanoma has historically been very poor, several agents approved since 2011 have shown promise in improving survival outcomes. A 2-year survival rate of 58% has been reported for nivolumab monotherapy in treatment-naïve patients with BRAF wild-type tumours from a phase 3 study.6 In a phase 1 study of heavily pretreated patients who received nivolumab monotherapy at 3 mg/kg, 2- and 5-year survival rates were 47% and 35%, respectively.15 More recently, a pooled analysis of data from a phase 1b study of pembrolizumab monotherapy showed a 2-year survival rate of 49% in previously treated and treatment-naïve patients (60% in treatment-naïve patients alone).16 It remains unclear how overall survival with nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy compares to that of initial anti-PD-1 monotherapy, and further follow-up of patients in the phase 3 CheckMate 067 trial may provide important information on this topic.

Significantly higher rates of confirmed objective responses were previously shown with nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs ipilimumab alone in CheckMate 0699 and in the phase 3 CheckMate 067 trial,7 with more complete responses. The current analysis showed that the median reduction in tumour burden with the combination, and a small increase in the median change in tumor burden with ipilimumab alone, persisted with continued follow-up. Responses remained durable, as evidenced by most responders remaining in response and median duration of response not having been reached. As previously reported for objective response rate,9 and extended here to include survival data, the apparently better efficacy of the combination vs ipilimumab alone was observed regardless of tumour PD-L1 expression at the 5% cutoff. Prior studies of anti-PD-1 monotherapy suggest better efficacy in patients with tumour PD-L1 expression ≥5% than in patients with PD-L1 expression <5%.8,13 The lack of such differences with combination therapy in CheckMate 069 may reflect T-cell infiltration into the tumour caused by ipilimumab, which then provides a more favourable tumour microenvironment for anti-PD-1 agents to act.9,14 However, efficacy outcomes were numerically different at the 1% cutoff in the current analysis, and.in the CheckMate 067 trial in which PD-L1 status was a stratification factor, longer progression-free survival and higher response rates with the combination were observed in patients with tumour PD-L1 expression ≥5% than in those with expression <5%.7

In general, there is a higher incidence of treatment-related adverse events with nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs ipilimumab alone.7,9 In the current analysis from CheckMate 069, the rates of treatment-related adverse events of any grade were 92% and 94% (grade 3–4, 54% and 20%) in the combination and ipilimumab alone groups, respectively, vs 91% and 93% (grade 3–4, 54% and 24%) at the time of the original database lock.9 The types and frequencies of treatment-related adverse events, and rate of events leading to discontinuation, were consistent with prior reports and there were no new safety signals. One exception is the incidence of colitis in patients who received ipilimumab alone, which was lower in the current analysis than previously reported in larger, phase 3 studies.7,8 Possible explanations include the generally better health of patients in the CheckMate 069 study compared with other studies, and the possible reassignment of grade 3 or 4 colitis upon follow-up.

Three study drug-related deaths were originally reported in CheckMate 069,9 but there were no new deaths related to treatment with follow-up. The results suggest a favorable benefit-risk profile for nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs ipilimumab alone, with the majority of adverse events having resolved in both groups using established safety guidelines involving immune-modulating medications as required. Further evaluation of the combination of anti-PD-1 agents and ipilimumab to improve the benefit-risk profile remains an area of particular interest. Recently reported data from the KEYNOTE-029 phase 1 study of pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg and ipilimumab 1 mg/kg in advanced melanoma, followed by pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg as maintenance therapy, showed an investigator-assessed response rate of 57% with 38% of patients experiencing a treatment-related adverse event of grade 3–4.17

In summary, the results of the current analysis from CheckMate 069 show encouraging survival outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with treatment-naïve advanced melanoma. Patients continue to be followed for overall survival in the CheckMate 069 trial. Additional information on survival outcomes with the nivolumab and ipilimumab combination in treatment-naïve advanced melanoma will be obtained by continued follow-up of patients in CheckMate 069 and upon maturity of overall survival data from the larger CheckMate 067 trial.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We performed a search to identify all studies evaluating combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma patients, with a focus on studies that included overall survival as either a primary, secondary, or exploratory endpoint. Our search included PubMed and congress abstracts from the annual meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the European Society of Medical Oncology/European Cancer Congress, and the Society for Melanoma Research, between January 1, 2012 and March 1, 2016. We used the search terms “PD-1”,“PD-L1”, “nivolumab”, “MK-3475”, “pembrolizumab”, “lambrolizumab”, “MPDL3280A”, “MEDI4736” AND “ipilimumab”; each search term AND “combination” with or without “overall survival”; “immune checkpoint inhibitor” AND “combination” with or without “overall survival”. Our search identified several ongoing studies evaluating combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors, most of which are early phase clinical trials without long-term follow-up of the patients for overall survival.

Added value of this study

Before this report, the longest survival follow-up for patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab was from a phase 1, dose-escalation study (CA209-004). In this relatively small study of untreated and previously treated patients, a 3-year overall survival rate of 68% was reported. To our knowledge, this is the first report of overall survival data from a randomised, controlled trial evaluating the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab as a first-line treatment for advanced melanoma.

Implications of all the available evidence

Combination therapy is emerging as an effective treatment option for advanced melanoma. Our survival data further support the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab as an effective first-line treatment option for patients with advanced melanoma, regardless of BRAF mutation status. The combination of these immune checkpoint inhibitors was approved for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma in the USA in January 2016 and in the European Union in May 2016.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this study and the clinical study teams. Financial support for the study was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Ward A. Pedersen, PhD and Cara Hunsberger of StemScientific, an Ashfield Company (Lyndhurst, New Jersey, USA), and were funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

FSH reports a consulting or advisory role with and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and a pending patent from ImmuneTarget. JC has served on advisory boards for and received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb. ACP has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has been paid to participate in a speakers’ bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb. CR has received honoraria from and had a paid consulting or advisory role with Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, and Roche. DFMcD has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, and Pfizer and received clinical research funding from Prometheus Labs. NM has received honoraria from and had a paid consulting or advisory role with Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche; provided expert testimony for Amgen, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Roche; and had travel or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Roche. MSE owns stock in Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Johnson & Johnson; has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck; received research funding from Alkermes, Argus, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ImmuNext, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Polynoma; and had travel or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck. DRM owns stock in Bristol-Myers Squibb; has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Atreca and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has been paid to participate in a speakers’ bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. AKS has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. MHT has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Eisai Inc., Onyx Pharmaceuticals, and PDX Pharma and received research funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celldex, Eisai Inc., Merck KGaA, and Novartis. PAO has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb and received research funding from Armo Biosciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MedImmune and Merck. CH is employed by and owns stock in Bristol-Myers Squibb. PG is employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and owns stock in Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck. JJ is employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. JDW has received honoraria from EMD Serono and Janssen Oncology; has had a paid consulting or advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Jounce Therapeutics, MedImmune, Merck, Polaris Pharma, Polynoma, and Ziopharm; received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, and Merck; is a co-investigator on an issued patent for DNA vaccines of cancer in companion animals; and has had travel or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. MAP reports advisory board participation for and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Contributors

FSH contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the report. JC, ACP, KG, DFMcD, GL, NM, JFG, SSA, MS, MSE, DRM, AKS, MHT, and PAO contributed to data collection and data interpretation. CR contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, and data interpretation. CH was the biomarker lead for the study. PG was the medical monitor for the study and JJ was the lead statistician for the current analyses. JDW and MAP contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the report.

Declaration of interests

KG, GL, JKG, SSA, and MS declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Garbe C, Eigentler TK, Keilholz U, Hauschild A, Kirkwood JM. Systematic review of medical treatment in melanoma: current status and future prospects. Oncologist. 2011;16:5–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott D, Haanen J, Chen TT, et al. MDX010-20 Investigators Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma patients surviving more than 2 years following treatment in a phase III trial (MDX010-20) Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2694–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1889–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkinson V, Ascierto PA, Long GV, et al. Two-year survival and safety update in patients with treatment-naïve advanced melanoma (MEL) receiving nivolumab or dacarbazine in CheckMate 066. Society for Melanoma Research Annual Meeting; San Francisco, California, USA. Nov 18–21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sznol M, Callahan MK, Kluger H, et al. Updated survival, response and safety data in a phase 1 dose-finding study (CA209-004) of concurrent nivolumab (NIVO) and ipilimumab (IPI) in advanced melanoma. Society for Melanoma Research Annual Meeting; San Francisco, California, USA. Nov 18–21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maio M, Grob JJ, Aamdal S, et al. Five-year survival rates for treatment-naïve patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1191–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–84. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:908–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase 1 trial. American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Apr 16–20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long GV, Atkinson V, Cebon JS, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus ipilimumab (ipi) for advanced melanoma: Results of the KEYNOTE-029 expansion cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):15S. abstr 9506. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.