Abstract

Introduction

As part of a control strategy current guidance in the UK recommends more intense surveillance of HbA1C levels among those of South-east Asian or Chinese ethnicity above specified BMI thresholds. The objective of this study was to determine whether disparities in the identification and control of diabetes in England persisted despite these guidelines and assess current strategies in light of these findings.

Methods

Data were extracted from the 2013 Health Survey for England that included ethnicity, BMI status and HbA1C levels. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses were used to examine relationships among undetected diabetes, poorly controlled diabetes and a range of covariates including ethnicity and BMI. Concentration indices were used to examine the socio-economic gradient in disease detection and control among and between ethnic groups.

Results

In regression models that controlled for a range of covariates Asians were found to have a 5% point higher risk of undetected diabetes than Whites. With respect to disease management, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis were found to be at a 28% point and 21% point higher risk of poor disease control respectively than Whites. Concentration indices revealed better disease control among more affluent Whites than poor Whites, no significant pattern between income and disease management was found among Pakistanis and poorer disease control was more evident among more affluent than poorer Bangladeshis.

Conclusion

In the UK current guidance recommends practitioners consider testing for diabetes among South-east Asians and Chinese where BMI exceeds 23. Our findings suggest that the risk experienced by Asians in disease detection is independent of BMI and may warrant a more active screening policy than currently recommended. With respect to disease management, our findings suggest that Indians and Pakistanis experience particularly high levels of poor disease control that may also be usefully reflected in guidance.

Keywords: Diabetes, Disparities, Ethnicity, Quality of care, UK

Introduction

Diabetes is characterised by an impaired ability to produce or respond to the hormone insulin. Between 90% and 95% of diabetics suffer from type 2 diabetes [29]. The disease is associated with a significant economic burden [1, 11, 12, 31, 38] that based on current trends seems set to increase in many countries [7, 39, 41]. That it can remain asymptomatic for several years contributes to this burden by allowing complications associated with it to accumulate that could be avoided were it detected and managed earlier [8, 10, 34]. While prompt identification and effective management are clearly important to avoiding such costs, several studies highlight not only the existence of a substantial prevalence of undiagnosed disease [4, 14, 17, 20, 28, 32] but also the existence of distinct patterns of undiagnosed disease. In the UK, Moody et al. [20], for example, found that males, those who are older (greater than 34 years) and those who are ethnic Asians were more likely to have undiagnosed diabetes. In the US, Menke et al (2015) [17] similarly found that rates of undiagnosed diabetes were higher among those who were older (45 years plus) and among Asians compared with Whites or younger persons.

Other studies point to similar patterns regarding glycaemic control among those with diagnosed diabetes. In Scotland, for example, Negandhi et al. [21] highlight higher levels of HbA1C (a measure of glycated haemoglobin used to define diabetes status) among those of Pakistani and Indian ethnicity compared to White Scottish, findings echoed elsewhere in the UK by James et al. [13]. Similar findings were evident in Sweden, where native Swedes exhibited better glycaemic control relative to those of South-east Asian ethnicity [26] and in the US where Non-hispanic Blacks [5, 9] and Mexican-American men [9] exhibited poorer glycaemic control relative to Whites.

Beyond ethnicity, studies provide mixed evidence regarding the role of socio-economic status (SES) in undiagnosed and poorly controlled diabetes. Some such as Lee et al (2015) [15] report a higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes among the less well off compared to the better off in Korea, as do Moody et al. [20] in the UK and Zhang et al. [40] in China. By contrast, others such as [33, 41] found no role for income in the US with similar findings by Rathmann et al. [25] in Germany. Similarly, concerning education, the evidence is mixed. Zhang et al. [41], Lee et al. [15] and Wilder et al. [33] found no role for education in undiagnosed diabetes while Moody et al. [20] found that those who were better educated were less likely to be undiagnosed. A similar pattern is found regarding glycaemic control among those diagnosed with diabetes. While Zhang et al. [40] and Moody et al. [20] found those who were better educated exhibited better glycaemic control than those who were not, Lee et al. [15] found no role for education in glycaemic control and Marden et al. [16] found numeracy but not literacy skills were important in glycaemic control.

Relationships reported in the literature can be seen to have informed screening guidelines for diabetes. In the UK, for example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend that general practitioners should consider blood tests for those aged 25 and over of South Asian or Chinese descent whose body mass index (BMI) is greater than 23 kg/m2 [22]. While a little different in terms of specifics, similar risk profiling related to age, obesity and ethnicity features in guidance offered by the US Preventive Services Task Force [30] though others have mooted the use of different thresholds for assessing diabetes risk related to ethnicity given different relationships between HbA1C and other measures of blood glucose across ethnic groups [2, 36].

The objective of this study is to ascertain whether current guidance related to diabetes screening in the UK appropriately reflects the differential risks of diabetes. We extend the analysis to examine whether distinct patterns in glycaemic control related to ethnicity are sufficient to warrant a reconsideration of disease management strategies in the UK. The article adds to current knowledge by extending the disaggregation of ethnicity to examine groups that have not yet been separately studied, specifically those of Bangladeshi ethnicity. We also compare socio-economic gradients in undiagnosed and poorly managed disease across ethnic groups to shed light on the factors that might explain their heterogeneous experience in diagnosis and disease control.

Methods

Data were extracted from the 2013 Health Survey for England (HSE). The HSE is an annual cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of community-dwelling individuals in England. Data are collected in two stages. In the first, respondents complete a health interview that includes details of self-reported conditions as well as the respondent’s socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, employment status, income, education, ethnicity, etc.). In the second stage the respondent is visited by a nurse who takes various physical measurements, records prescribed medication and takes biological samples. In most years approximately 8000 adults complete the first stage of the survey and around 6000 the second stage. The disease focus of the nurse visit varies from year to year. In 2013 a focus was placed on diabetes. Further details on the survey are available in [18]. All analyses reported here are based on this previously conducted study and do not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Ethnicity was examined regarding Whites, Blacks and Asians and, when sample size permitted, within Asians with respect to Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Indian and other Asians based on self-reported status. Undiagnosed diabetes was a constructed variable based on the respondent having an HbA1C level over 6.5% while self-reporting s/he was not diabetic. Poorly controlled diabetes was a constructed variable based on the respondent reporting diabetes as a condition s/he experienced and having an HbA1C above 6.5%. Other variables used in the analysis and their precise definition are presented in Table 4 of “Appendix 1”.

The distribution of HbA1C was graphed and compared visually by ethnic group. Descriptive statistics (mean and 95% confidence interval) were estimated and compared by ethnic group regarding the proportion of respondents who had undiagnosed and poorly controlled diabetes. Erryeger’s (2009) corrected concentration indices were estimated using the conindex commands [23] by ethnic group regarding undiagnosed and poorly controlled disease. The concentration index measures the distribution of undiagnosed (and poorly controlled) diabetes in the sample relative to the distribution of income. The index is bounded by values of 1 and −1. An over-representation of undiagnosed diabetes among those with low income would be reflected in a negative index and an over-representation among those with high income by a positive index. Logistic regression analyses were undertaken in which undiagnosed and poorly controlled diabetes respectively were regressed on functions that controlled for age, BMI, ethnicity, income, education and smoking status. To allow for the impact of differential access/use of GP services in diabetes detection and control, whether the respondent had visited the GP in the last 12 months was included as a covariate in the regression analyses. This allowed us to provide a sharper focus on the success or otherwise of current primary care screening practices in the detection and management of diabetes across ethnic and socio-economic groups. Confirmatory analyses were undertaken in which BMI was included as a series of categorical variables in the regression analyses with separate thresholds used to define groups at risk based on their relative risks of complications related to obesity. Among Chinese, thresholds were based on a WHO consensus statement [37]; among Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis they were based on a consensus statement from a group of Indian clinicians [19] and for other ethnicities on existing BMI classifications [37].

Results

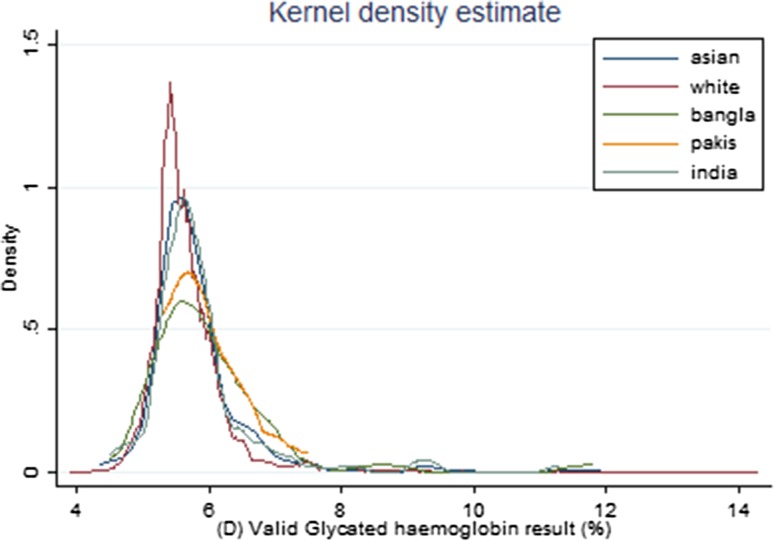

Figure 1 displays the distribution of HbA1C by ethnic groups. As can be seen not only is mean HbA1C higher among those of Asian ethnicity relative to Whites but the distributions are also quite different among specific ethnic Asian groups. The distribution of Asian’s HbA1C is typically centred to the right of those for Whites, for example, while the distribution for Bangladeshis exhibits a heavier tail than that for Pakistanis. In Table 1 descriptive statistics reveal that incomes among Pakistanis and Bangladeshis is significantly lower than those of Indians and Whites, the latter also tending to have higher levels of education.

Fig. 1.

Kernel density estimate. kernel = epanechnikov, bandwidth = 0.1362

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| Income | Median | Mean | Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | 24,718.31 | 33,612.67 | 32,979.14 | 34,246.20 |

| Asians | 17,769.78 | 27,664.03 | 25,249.65 | 30,078.41 |

| Bangladesh | 9919.68 | 12,023.68 | 9684.823 | 14,362.54 |

| Pakistani | 13,307.09 | 20,095.06 | 15,542.9 | 24,647.22 |

| Indians | 25,514.02 | 34,608.66 | 30,471.51 | 38,745.81 |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Having visited GP | 8696 | 0.7832 | 0.4121 | 0 | 1 |

| Age group | |||||

| 25–34 | 8795 | 0.1806 | 0.3847 | 0 | 1 |

| 35–44 | 8795 | 0.1532 | 0.3602 | 0 | 1 |

| 45–54 | 8795 | 0.2543 | 0.4355 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 8764 | 0.2708 | 0.4444 | 0 | 1 |

| BMI | 8798 | 25.9056 | 6.1745 | 12.4421 | 63.0914 |

| Smoke | |||||

| Ex-occasional smoker | 8725 | 0.3221 | 0.4673 | 0 | 1 |

| Never smoker | 8725 | 0.4834 | 0.4998 | 0 | 1 |

| Ethnic | |||||

| Black | 10,946 | 0.0293 | 0.1687 | 0 | 1 |

| Asian | 10,946 | 0.0732 | 0.2604 | 0 | 1 |

| Mixed | 10,946 | 0.0200 | 0.1400 | 0 | 1 |

| Any other | 10,946 | 0.0092 | 0.0956 | 0 | 1 |

| Male | 10,980 | 0.4577 | 0.4982 | 0 | 1 |

| Tertile of income | |||||

| Second tertile | 8790 | 0.3226 | 0.4675 | 0 | 1 |

| Highest tertile | 8790 | 0.3373 | 0.4728 | 0 | 1 |

In Table 2 the concentration indices in which equivalised household income is used as a ranking variable and undiagnosed and poorly controlled diabetes are used as health outcomes are presented. Small sample sizes precluded the estimation of indices for each specific ethnic group regarding undiagnosed disease. As the table shows, however, distinct patterns between Whites and Asians exist and regarding poorly controlled diabetes distinct patterns are evident among different ethnic groups of South-east Asians. While a pro-poor gradient is exhibited regarding poor control for Whites and Indians for example (that is, more poor Whites and Indians relative to their representation in the sample have poorly controlled disease), there is no significant gradient regarding Pakistanis and a pro-rich gradient is evident regarding Bangladeshis.

Table 2.

Concentration indices regarding diabetes control and diagnosis by ethnic group

| Poorly controlled group | Concentration index | Confidence interval | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poorly controlled (Bangladesh) | 0.09375 | 0.0406 | 0.1470 | 32 |

| Poorly controlled (Pakistani) | −0.1600 | −0.3455 | 0.0255 | 10 |

| Poorly controlled (Indians) | −0.0400 | −0.0615 | −0.0215 | 68 |

| Poorly controlled (Asians) | −0.01951 | −0.0273 | −0.0117 | 167 |

| Poorly controlled (Whites) | −0.0528 | −0.5283 | −0.0525 | 3447 |

| Undiagnosed (all) | −0.0543 | −0.0547 | −0.0540 | 3747 |

| Undiagnosed (White) | −0.0429 | −0.0433 | −0.0426 | 3447 |

| Undiagnosed (Black) | −0.0048 | −0.0099 | 0.0195 | 65 |

| Undiagnosed (Asian) | −0.0719 | −0.0780 | −0.0658 | 167 |

In Table 3 the results of a series of logistic regression analyses are presented. Regarding undiagnosed disease and controlling for having seen a GP in the past 12 months, those of Asian ethnicity, those who are older, who are male and who have a higher BMI are seen to be more likely to have undiagnosed disease compared to the relevant comparator groups. Those who have higher incomes are less likely to be undiagnosed compared to those with lower incomes. Regarding poorly controlled disease and again controlling for having seen a GP in the past 12 months, those who are Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi are seen to be more likely to have poorly controlled disease compared to Whites. While Blacks are also more likely to have poorly controlled disease this only attains borderline significance. Those who are better educated and those with higher incomes are seen to be less likely to have poorly controlled disease compared to those less well educated and those with lower incomes. As with undiagnosed, those who are older and with higher BMI are more likely to have poorly controlled diabetes. Confirmatory analysis of undiagnosed and poorly controlled disease are reported in Table 5 of Appendix 1. As can be seen Asians remain more likely to experience undiagnosed disease relative to Whites adjusting for Chinese and Indian specific BMI thresholds. For glycaemic control, Pakistanis and Indians with diabetes remain significantly less likely to exhibit glycaemic control than Whites. While Bangladeshis appeared more likely to exhibit poor glycaemic control this failed to attain statistical significance.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses

| Variables | Undiagnosed diabetes margins | Poorly controlled diabetes margins |

|---|---|---|

| visit_GP | 0.0114 (0.00789) | 0.0273** (0.0107) |

| Age group (ref.: 16–44) | ||

| 45–54 | 0.0132** (0.00621) | 0.0215*** (0.00762) |

| 55–64 | 0.0327*** (0.00872) | 0.0379*** (0.00922) |

| 65+ | 0.0416*** (0.00878) | 0.0709*** (0.00977) |

| Education (age person finished continuous full-time education ≥19) | −3.72e−05 (0.00751) | −0.0217** (0.00986) |

| BMI | 0.00327*** (0.000546) | 0.00461*** (0.000620) |

| Ex-occasional/regular smoker | −0.0147 (0.00988) | 0.00557 (0.0103) |

| Current smoker | −0.0143 (0.00981) | −0.00210 (0.0100) |

| Ethnicity (ref.: whites) | ||

| Black | 0.0777* (0.0434) | |

| Indian | 0.142*** (0.0522) | |

| Pakistani | 0.212*** (0.0735) | |

| Bangladeshi | 0.284** (0.129) | |

| Chinese and other Asian | 0.0194 (0.0453) | |

| Chinese | ||

| Other asian | ||

| Mixed | −0.00998 (0.0255) | |

| Any other | 0.0451 (0.0715) | |

| Male | 0.0154*** (0.00580) | 0.0210*** (0.00698) |

| 17,402–34,788 | 0.00254 (0.00752) | −0.00294 (0.00860) |

| >34,788 | −0.0162** (0.00686) | −0.0178** (0.00866) |

| Black | 0.0188 (0.0199) | |

| Asian | 0.0467*** (0.0121) | |

| Observations | 3205 | 3408 |

Note: margins report average partial effects. Figures in parentheses report standard errors

*** Significant at p < 0.01; ** significance at p < 0.05; * significance at p < 0.1

Discussion

Previous work has shown that in the UK, Asians are at greater risk of their diabetes going undiagnosed and when diagnosed of it being poorly controlled [13, 20, 21]. This is reflected to an extent in current guidance on screening where NICE [22] suggest that GPs and practice nurses “…should…consider a blood test for those aged 25 and over of South Asian or Chinese descent whose body mass index (BMI) is greater than 23 kg/m” [22]. Our analyses reveal that despite this guidance in 2013 Asians remained more likely to have undiagnosed diabetes than Whites and among those with diagnosed diabetes there is evidence that Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in particular were more likely to exhibit poor glycaemic control. That in both instances elevated risks existed in regressions where contact with doctor services was controlled for indicates that this is not simply an issue of potentially lower service uptake by these groups but also of the manner in which these groups are served.

Regarding undiagnosed disease, as seen in Table 3, the magnitude of the penalty experienced by Asians is significant and independent of age and BMI. (These results are supported by confirmatory analysis reported in Table 5 “Appendix 1”.) The marginal effect of Asian ethnicity on risk of undiagnosed disease is equivalent to approximately 14 BMI points. That is, it is equivalent to moving someone from underweight to obese. Given the effects of ethnicity are independent of age and BMI, it is debatable whether the ethnicity risk premium is appropriately reflected in current guidance, which refers to consideration being given to testing conditional on age and BMI. In short, it could be argued that advice might usefully be rephrased as “GPs and practice nurses should offer a blood test to persons of South Asian or Chinese descent regardless of age and BMI status”. While such a change would require an assessment of its cost effectiveness and budgetary impact, it seems reasonable that it should at a minimum be investigated.

Regarding the management of diabetes, as seen in Table 3, currently those of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi descent exhibit poorer glycaemic control relative to Whites controlling for age, BMI and socio-economic status. (These results are largely supported by confirmatory analyses in Table 5 of the “Appendix 1”. While the result regarding Bangladeshis failed to attain statistical significance this may indicate a poorer correlation in risk between Indian-specific BMI thresholds and disease risk among Bangladeshis.) Again the extent of elevated risk can be assessed by comparison with the change in BMI that would be required to raise risk by an equivalent amount. In Table 3 with respect to diabetic Pakistanis, the marginal effect of their ethnicity on having an HbA1C measure that exceeds 6.5% is equivalent to a change in BMI of approximately 46 BMI points (moving from underweight to extreme obesity).

Given this, it is questionable whether current incentives contained within the UK’s Quality Outcomes Framework are sufficient or are sufficiently targeted to address poor glycaemic control among several Asian groups.

As with the failure to detect diabetes, failure to control blood sugar among diabetics will impact directly on the economic burden of the disease and on the distribution of that burden. In the UK, the estimated cost of diabetes in 2010/11 was £23.7 billion of which £9 billion was estimated to be born directly by patients and their families in the form of higher absenteeism, presenteeism, informal care and mortality [11]. It seems reasonable to conclude that a substantial proportion of this burden might be avoided if the disease is detected earlier and effective management adopted before complications associated with it can accumulate [8, 10, 34]. This has the potential to reduce both the burden of disease and disparities in the distribution of that burden. As with diagnosis, using ethnicity to help target disease management efforts would have to be assessed in terms of its cost effectiveness and budgetary impact. As with diagnosis, however, that such a policy should be investigated seems reasonable.

Consideration of our results regarding concentration indices alongside regression analyses provides potentially valuable insights into the source of difference between ethnic groups. Both Asians and Whites exhibit a pro-poor pattern of undiagnosed disease, that is, one in which those who are less well off are over-represented among undetected diabetics relative to their representation in the population. This indicates a role for poverty in the failure to detect diabetes, an inference supported by the statistical significance of income in the regression analysis. The picture may be somewhat more complex than this though. Thus while the concentration index among Asians is significantly higher in absolute terms than that for Whites—suggesting poverty among Asians may have a particularly deleterious effect—the heterogeneous experience of Asians regarding glycaemic control may well be mirrored in respect to undiagnosed disease. Sample size meant it was not possible for us to pursue this line of enquiry but it is one that warrants further research.

As noted by Rhodes et al. [27], with specific reference to Bangladeshi diabetics, language, culture and poverty may combine to present particular barriers in terms of both access to care and the quality of care received when accessed. The ability to afford transport, prolonged visits to Bangladesh during which access to ongoing care may not be possible as well as cultural issues around women attending clinics were cited as issues in access and quality of care. Such issues may present differential barriers to those who are relatively more recent migrants to England than those who have a more established history in the country. It is notable, for example, that among South-east Asians, in terms of waves of migrants Indians preceded Pakistanis who in turn preceded Bangladeshis to the UK [24]. This sequence mirrors the rank order of marginal effects in diabetes control suggesting not just language but assimilation more generally may contribute to differences between ethnicities in observed glycaemic control. Unfortunately, it was not possible to explore the relationship among migration history, diagnosis and glycaemic control with the data available in the Health Survey for England as information on how recently families migrated was not recorded. This area though does offer a potentially fruitful line of future investigation.

Beyond ethnicity the negative association among disease control, income and education after controlling for use of GP services are consistent with the predictions of the Grossman health investment model [6]. This model predicts that as income increases and/or as education increases so too will investments in health. The relative magnitude of the two marginal effects in this case is instructive. Finishing education after 19 years of full-time education compared to earlier was more than equivalent to a move from the lowest to the highest income tertile (a change that would involve approximately £17,386 per annum in this sample). This suggests that in terms of its impact on health, education has a larger effect than income. These findings regarding the relative magnitude of education and income are consistent with those of other authors who show education to have a higher impact on health [3, 35] and health-improving behaviours [3]. They also underscore the limitations of healthcare as a means of addressing broader socio-economic disparities though. Whether more forceful screening strategies, health promotion and aggressive disease management framed around personalised medicine can address some of the disparities noted in this study warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated that after controlling for use of GP services Asians are at higher risk of undetected diabetes than are Whites in England. It has shown that among Asians distinct patterns in glycaemic control are evident with those of Pakistani and Indian descent experiencing particular disadvantage and evidence indicating this may also extend to Bangladeshis. Our analysis suggests that current guidance on screening for diabetes may not adequately reflect the relative risks experienced by ethnic minorities and barriers may exist that limit the effectiveness of current practice regarding glycaemic control. Our findings on socio-economic status, however, also underscore the limitations of healthcare to address inequalities whose origins reflect broader inequalities in society related to education and incomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by funding HRB RL/2013/16 for the study's conduct and publication costs. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Mimi Xiao and Ciaran O’Neill have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the UK Data Archive repository http://www.data-archive.ac.uk.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Appendix 1

Table 4.

Definition of variables used in regression analyses

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Visited GP | Having visited GP in the past 12 months |

| Age group | 16–24 |

| 25–34 | |

| 35–44 | |

| 45–54 | |

| Education | Age person finished continuous full-time education. =1 if ≥19 |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| Smoking status | Never smoker |

| Ex-occasional smoker | |

| Never smoker | |

| Ethnic | Black |

| Asian | |

| Mixed | |

| Any other | |

| Gender | Male = 1 |

| Tertile of income | Lowest tertile (≤17,402) |

| Second tertile (17,402–34,788) | |

| Highest tertile (>34,788) | |

| BMI categories | |

| Others1 | |

| Underweight | Below 18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 |

| At risk (overweight) | 25–29.9 |

| At higher risk (obese) | 30+ |

| Chinese1 | |

| Underweight | Below 18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–22.9 |

| At risk (overweight) | 23–27.49 |

| At higher risk (obese) | 27.5+ |

| Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi2 | |

| Underweight | <18 |

| Normal weight | 18–22.9 |

| At risk (overweight) | 23–24.9 |

| At higher risk (obese) | 25+ |

Table 5.

Logistic regression analyses

| Variables | Undiagnosed margins | Poor margins |

|---|---|---|

| Visit_GP | 0.0174** (0.00800) | 0.0353*** (0.0112) |

| Age group (ref.: 16–44) | ||

| 45–54 | 0.0132** (0.00579) | 0.0266*** (0.00775) |

| 55–64 | 0.0359*** (0.00898) | 0.0426*** (0.00945) |

| 65+ | 0.0409*** (0.00848) | 0.0752*** (0.00935) |

| edu | −0.00628 (0.00743) | −0.0254** (0.0101) |

| Obesity status (ref.: underweight/normal weight) | ||

| Over | 0.00300 (0.00511) | 0.00638 (0.00650) |

| Obese | 0.0396*** (0.00742) | 0.0654*** (0.00876) |

| Smoking status (ref.: non-smoker) | ||

| Ex-occasional/regular smoker | −0.00944 (0.00909) | 0.00687 (0.0102) |

| Current smoker | −0.00836 (0.00886) | −0.000764 (0.00989) |

| Ethnicity (ref.: Whites) | ||

| Black | 0.0798* (0.0450) | |

| Indian | 0.0789** (0.0395) | |

| Pakistani | 0.150** (0.0639) | |

| Bangladeshi | 0.118 (0.0878) | |

| Chinese and other Asian | −0.00110 (0.0351) | |

| Mixed | −0.00943 (0.0333) | |

| Any other | 0.0652 (0.0663) | |

| Male | 0.0163*** (0.00569) | 0.0175** (0.00700) |

| Tertile of income (ref.: <17,402) | ||

| 17,402–34,788 | 0.00156 (0.00744) | −0.00576 (0.00856) |

| >34,788 | −0.0153** (0.00670) | −0.0218** (0.00861) |

| Black | 0.0313* (0.0171) | |

| Asian | 0.0351*** (0.0124) | |

| Observations | 3397 | 3651 |

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/1EFBF060408FF00A.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diabet Care. 2013;36:1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen RM, Smith EP, Arbabi S, Quinn CT, Franco RS. Do red blood cell indices explain racial differences in the relationship between hemoglobin A1c and blood glucose? J Pediatrics. 2016;176:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler DM, Lleas-Muney A. Education and health: evaluating theories and evidence. NBER working paper 12352, 2006. http://www.nber.org/papers/w12352. Accessed May 2017.

- 4.Dall TM, Yang W, Halder P, Franz J, Byrne E, Semilla AP, Stuart B. Type 2 diabetes detection and management among insured adults. Population Health Metrics. 2016;14(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egede LE, Mueller M, Echols CL, Gebregziabher M. Longitudinal differences in glycemic control by race/ethnicity among veterans with type 2 diabetes. Med Care. 2010;48(6):527–533. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d558dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Political Econ. 1972;80(2):223–255. doi: 10.1086/259880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Patterson JK. Cardiovascular risk factors in confirmed prediabetic individuals: does the clock for coronary heart disease start ticking before the onset of clinical diabetes? JAMA. 1990;263(21):2893–2898. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440210043030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Care. 1999;22(3):403–408. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris MI, Klein R, Welborn TA, Knuiman MW. Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4–7 yr before clinical diagnosis. Diabet Care. 1992;15(7):815–819. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, Taylor M, Varley D. Estimating the current and future costs of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med. 2012;29(7):855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs E, Hoyer A, Brinks R, Icks A, Kuß O, Rathmann W. Healthcare costs of Type 2 diabetes in Germany. Diabet Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.James GD, Baker P, Badrick E, Mathur R, Hull S, Robson J. Ethnic and social disparity in glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; cohort study in general practice 2004–9. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(7):300–308. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Wong R, Ottenbacher KJ, Al Snih S. Prediabetes, undiagnosed diabetes, and diabetes among Mexican adults: findings from the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HY, Hahm MI, Choi KS, Jun JK, Suh M, Nam CM, Park EC. Different socioeconomic inequalities exist in terms of the prevention, diagnosis and control of diabetes. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(6):961–965. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marden S, Thomas PW, Sheppard ZA, Knott J, Lueddeke J, Kerr D. Poor numeracy skills are associated with glycaemic control in Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021–1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mindell J, Biddulph JP, Hirani V, Stamatakis E, Craig R, Nunn S, Shelton N. Cohort profile: the health survey for England. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1585–1593. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra A, Chowbey P, Makkar BM, Vikram NK, Wasir JS, Chadha D, et al. Consensus Group. Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moody A, Cowley G, Ng Fat L, Mindell JS. Social inequalities in prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and impaired glucoseregulat ion in participants in the Health Surveys for England series. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010155. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negandhi PH, Ghouri N, Colhoun HM, Fischbacher CM, Lindsay RS, McKnight JA, Petrie J, Philip S, Sattar N. Wild SH; Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Ethnic differences in glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus living in Scotland. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NICE, Type 2 diabetes: prevention in people at high risk Guidance PH 38, 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph38/chapter/1-Recommendations#flowchart-identifying-and-managing-risk-of-type-2-diabetes. Accessed May 11 2017.

- 23.O’Donnell O, O’Neill S, Van Ourti T, Walsh B. conindex: estimation of concentration indices. Stata J. 2016;16(1):112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of National Statistics, 2013. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160107164635/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_346219.pdf. Accessed May 11 2017.

- 25.Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, Giani G, Holle R, Meisinger C, Mielck A. Sex differences in the associations of socioeconomic status with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the elderly population: the KORA Survey 2000. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(6):627–633. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawshani A, Svensson AM, Rosengren A, Zethelius B, Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S. Impact of ethnicity on progress of glycaemic control in 131,935 newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide observational study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. BMJ Open. 2005;5(6):e007599. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes P, Nocon A, Wright J. Access to diabetes services: the experiences of Bangladeshi people in Bradford, UK. Ethnicity and Health. 2003;8(3):171–188. doi: 10.1080/1355785032000136407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosella LC, Lebenbaum M, Fitzpatrick T, Zuk A, Booth GL. Prevalence of prediabetes and undiagnosed diabetes in Canada (2007–2011) according to fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c screening criteria. Diabet Care. 2015;38(7):1299–1305. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubino F. Is type 2 diabetes an operable intestinal disease? A provocative yet reasonable hypothesis. Diabet Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S290–S296. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu AL. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):861–868. doi: 10.7326/M15-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sortsø C, Green A, Jensen PB, Emneus M. Societal costs of diabetes mellitus in Denmark. Diabet Med. 2016;33(7):877–885. doi: 10.1111/dme.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamayo T, Rosenbauer J, Wild SH, Spijkerman AMW, Baan C, Forouhi NG, Rathmann W. Diabetes in Europe: an update. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilder RP, Majumdar SR, Klarenbach SW, Jacobs P. Socio-economic status and undiagnosed diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Practice. 2005;70(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams R, Van Gaal L, Lucioni C. Assessing the impact of complications on the costs of Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45(7):S13–S17. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):816–820. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolffenbuttel BH, Herman WH, Gross JL, Dharmalingam M, Jiang HH, Hardin DS. Ethnic differences in glycemic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Care. 2013;36(10):2931–2936. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organisation Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang W, Dall TM, Halder P, Gallo P, Kowal SL, Hogan PF, Petersen M. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2012. Diabet Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zghebi SS, Steinke DT, Carr MJ, Rutter MK, Emsley RA, Ashcroft DM (2017) Examining trends in type 2 diabetes incidence, prevalence and mortality in the UK between 2004 and 2014. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Zhang H, Xu W, Dahl AK, Xu Z, Wang HX, Qi X. Relation of socio-economic status to impaired fasting glucose and Type 2 diabetes: findings based on a large population-based cross-sectional study in Tianjin. China Diabet Med. 2013;30(5):e157–e162. doi: 10.1111/dme.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang N, Yang X, Zhu X, Zhao B, Huang T, Ji Q. Type 2 diabetes mellitus unawareness, prevalence, trends and risk factors: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2010. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(2):594–609. doi: 10.1177/0300060517693178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the UK Data Archive repository http://www.data-archive.ac.uk.