Abstract

Objective:

To report the CNS syndromes of patients ≥60 years of age with antibodies against neuronal surface antigens but no evidence of brain MRI and CSF inflammatory changes.

Methods:

This was a retrospective clinical analysis of patients with antibodies against neuronal surface antigens who fulfilled 3 criteria: age ≥60 years, no inflammatory abnormalities in brain MRI, and no CSF pleocytosis. Antibodies were determined with reported techniques.

Results:

Among 155 patients ≥60 years of age with neurologic syndromes related to antibodies against neuronal surface antigens, 35 (22.6%) fulfilled the indicated criteria. The median age of these 35 patients was 68 years (range 60–88 years). Clinical manifestations included faciobrachial dystonic seizures (FBDS) in 11 of 35 (31.4%) patients, all with LGI1 antibodies; a combination of gait instability, brainstem dysfunction, and sleep disorder associated with IgLON5 antibodies in 10 (28.6%); acute confusion, memory loss, and behavioral changes suggesting autoimmune encephalitis (AE) in 9 (25.7%; 2 patients with AMPAR, 2 with NMDAR, 2 with GABAbR, 2 with LGI1, and 1 with CASPR2 antibodies); and rapidly progressive cognitive deterioration in 5 (14.3%; 3 patients with IgLON5 antibodies, 1 with chorea; 1 with DPPX antibody–associated cerebellar ataxia and arm rigidity; and 1 with CASPR2 antibodies).

Conclusions:

In patients ≥60 years of age, the correct identification of characteristic CNS syndromes (FBDS, anti-IgLON5 syndrome, AE) should prompt antibody testing even without evidence of inflammation in MRI and CSF studies. Up to 15% of the patients developed rapidly progressive cognitive deterioration, which further complicated the differential diagnosis with a neurodegenerative disorder.

The characterization of antibodies against neuronal surface antigens as biomarkers of treatable neurologic syndromes has changed the diagnostic approach to encephalitis and other inflammatory CNS disorders.1 However, in patients ≥60 years of age with these syndromes, the differential diagnosis may be complicated by the fact that signs of inflammation on neuroimaging or CSF studies may be absent. Moreover, some antibody-associated CNS syndromes such as the recently described syndrome with IgLON5 antibodies2 rarely show inflammatory abnormalities.

We report the CNS syndromes of patients ≥60 years of age with antibodies against neuronal surface antigens but no evidence of inflammatory changes in brain MRI and CSF at initial evaluation or repeat studies when available.

METHODS

We retrospectively identified patients ≥60 years of age whose serum or CSF samples were sent to our laboratory for determination of neuronal antibodies. Studies included rat brain immunohistochemistry and a cell-based assay on HEK293 cells expressing LGI1, CASPR2, IgLON5, DPPX, mGluR5, NMDAR, AMPAR, GABAb receptor, or GABAa receptor as reported.3 Exclusion criteria included syndromes involving predominantly the spinal cord or the peripheral nervous system.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Written consent for the storage and use of the samples for research purposes was obtained from patients. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain.

RESULTS

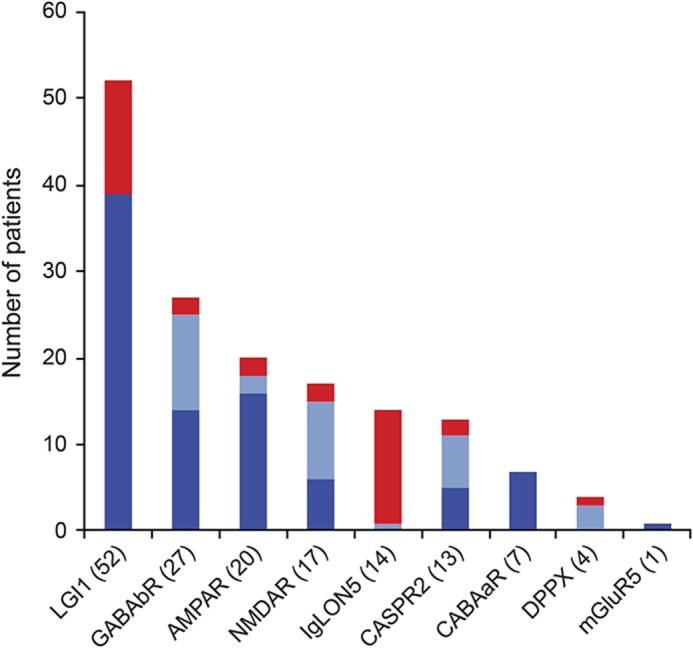

Of 155 patients with age ≥60 years and antibodies against neuronal surface antigens, 35 (22.6%) fulfilled the indicated criteria of CNS syndromes without evidence of inflammation. Among those 155 patients, the most common antibody was LGI1 (figure 1). Except for patients with IgLON5 antibodies who usually did not show evidence of inflammation (93%), the frequency of patients with this profile ranged from 25% (LGI1 antibodies) to 7% (GABAb receptor antibodies) (figure 1). Compared to younger patients (age <60 years), the frequency of this noninflammatory profile was higher in patients with LGI1 (25% vs 3%, p = 0.01) and IgLON5 (93% vs 50%, p = 0.03) antibodies (figure e-1 at Neurology.org).

Figure 1. Distribution of patients according to antibody type.

Frequency of patients ≥60 years of age with (blue) or without (red) CSF pleocytosis or inflammatory changes in the brain MRI. Number of cases for each antibody is shown in parentheses. Dark blue in the column indicates number of patients with brain MRI findings compatible with encephalitis; light blue indicates number of cases with normal MRI and CSF pleocytosis.

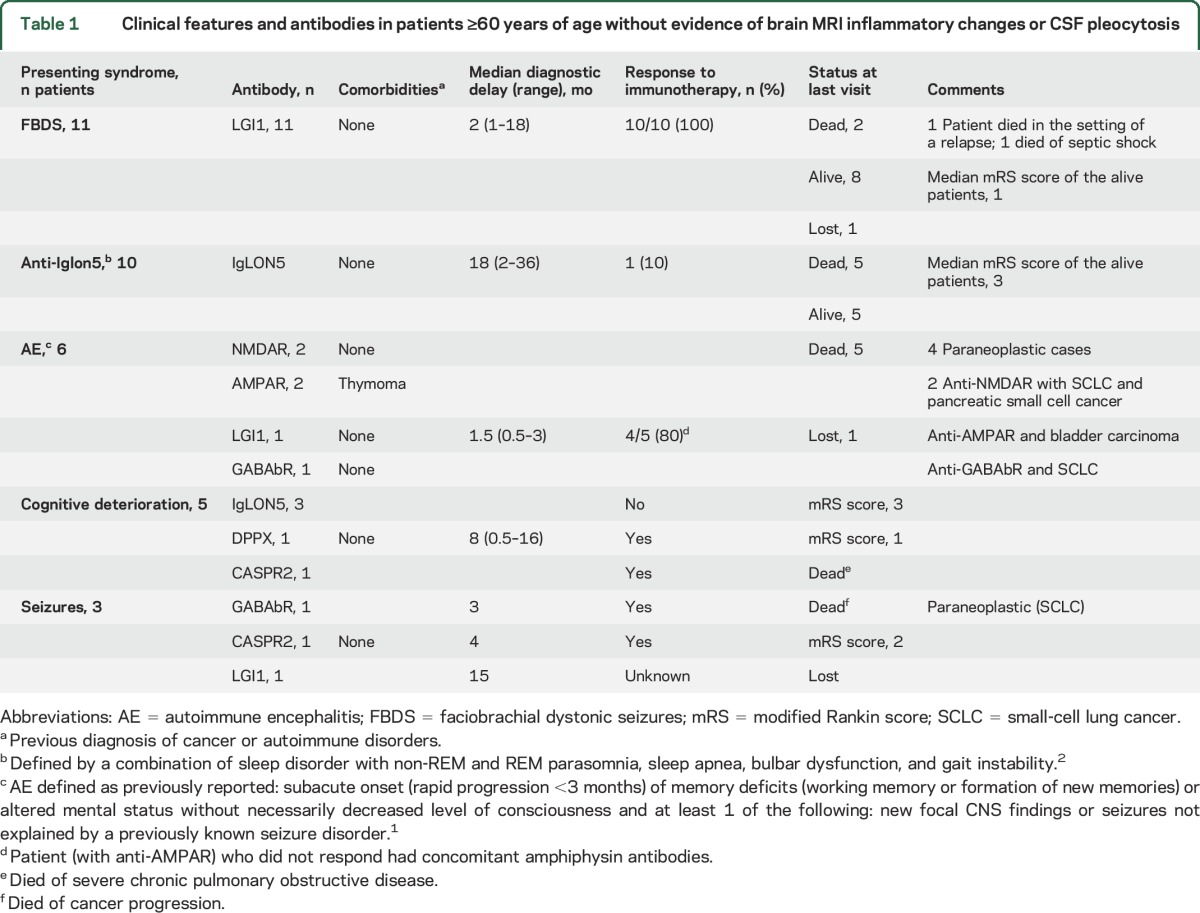

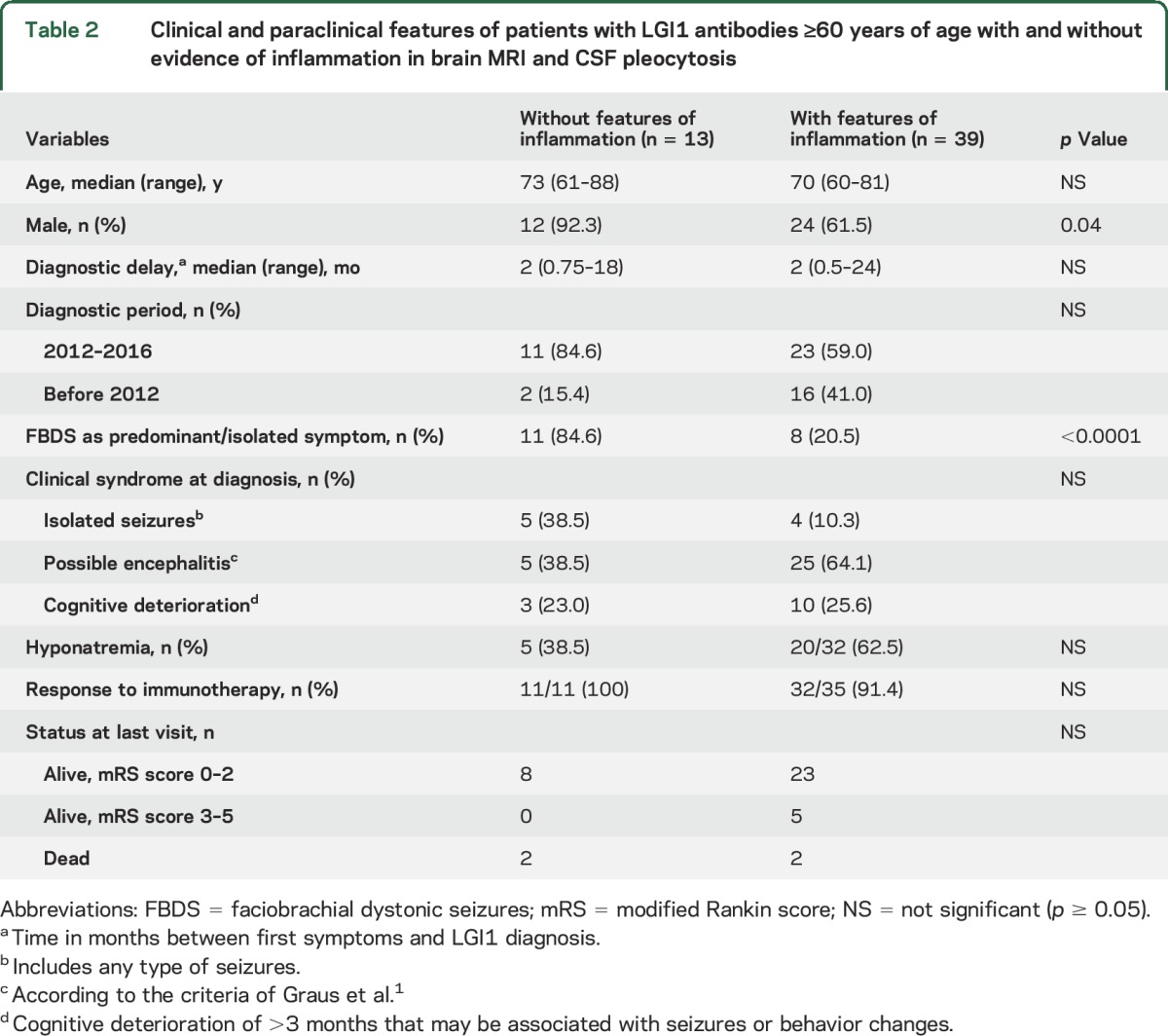

Eleven of 13 patients with LGI1 antibodies presented with faciobrachial dystonic seizures (FBDS), which were the most predominant or the only symptom for several weeks or months. All patients improved with immunotherapy (table 1). When these 13 patients were compared with the group of 39 patients of similar age range and LGI1 antibodies but with evidence of MRI or CSF inflammatory changes (e.g., limbic encephalitis or pleocytosis), those without inflammatory changes were more likely to present with isolated or predominant FBDS (85% vs 20%, p < 0.001) (table 2). As far as the remaining antibodies are concerned, no significant differences were observed between patients with or without inflammatory changes except for a longer diagnostic delay in those without inflammatory changes (median 3 vs 1 month, p < 0.005) (table e-1).

Table 1.

Clinical features and antibodies in patients ≥60 years of age without evidence of brain MRI inflammatory changes or CSF pleocytosis

Table 2.

Clinical and paraclinical features of patients with LGI1 antibodies ≥60 years of age with and without evidence of inflammation in brain MRI and CSF pleocytosis

Thirteen patients had IgLON5 antibodies; of these, 10 (77%) developed a clinical course characterized by bulbar symptoms (n = 9), gait instability (n = 8), and sleep dysfunction (n = 8), and the other 3 patients developed progressive cognitive decline (discussed later). The sleep dysfunction was characterized by episodes of vocalizations and purposeful-appearing motor activity during non-REM sleep, abnormal REM sleep, stridor, and apneas. None of the patients with IgLON-5 antibody showed substantial improvement with immunotherapy, including steroids in 8 patients, intravenous immunoglobulins in 7, and rituximab in 4 (table 1).

Nine (25.7%) patients presented with a clinical syndrome suggesting autoimmune encephalitis (AE), including acute episodes in a few days or weeks of confusion, memory loss, personality change, delirium, and agitation that resulted in initial psychiatric consultation in 2 of them. In 3 patients (1 with GABAb receptor, 1 with CASPR2, and 1 with LGI1 antibodies), the symptoms of AE were preceded by isolated epileptic seizures during 3, 4, and 15 months, respectively (table 1). In 2 of the remaining 6 patients, the syndrome evolved to typical anti-NMDAR encephalitis, and in 3 (1 with LGI1, 1 with GABAb receptor, and 1 with AMPAR antibodies), the syndrome suggested limbic encephalitis despite the normal MRI. Another patient with AMPAR antibodies, delirium, and decreased level of consciousness with extensor plantar responses fully recovered after treatment with steroids (table 1).

Five (14.3%) patients (3 with IgLON5, 1 with DPPX, and 1 with Caspr2 antibodies) developed progressive cognitive decline including memory loss or dysfunction of other cognitive domains but without seizures or psychiatric symptoms. One of these IgLON5 antibody–positive patients also had chorea and the distinctive sleep disorder. The patient with DPPX antibodies developed dementia, gait ataxia, and rigidity preceded by diarrhea. The patient with CASPR2 antibodies had a pure amnestic syndrome without other symptoms.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that in patients ≥60 years of age with normal brain MRI and no CSF pleocytosis, the presence of antibodies against neuronal surface antigens is associated with well-characterized neurologic disorders such as FBDS,4 anti-IgLON5 syndrome,2 and AE1 and is less frequently associated with rapidly progressive dementia.5 A recent study indicates that basal ganglia MRI abnormalities can be detected in 42% of patients with FBDS.6 We did not see these MRI changes in our patients with isolated FBDS, but the MRIs were not centrally reviewed. However, in a series of 39 patients with anti-LGI1 encephalitis in whom brain MRIs were reassessed by a neuroradiologist, basal ganglia hyperintensities were seen in only 1 patient.7

The identification of IgLON5 antibodies was crucial for the initial clinical characterization of the core symptoms of this disease. Neuropathologic findings show a novel tauopathy suggesting a primary neurodegenerative etiology,2 but the possibility of pathogenic immune mechanisms is also suggested by experiments showing that antibodies cause an irreversible decrease of the density of neuronal surface IgLON5. Although our patients were refractory to immunotherapy, a few case reports suggest that early treatment may be effective.8

The most frequently used diagnostic criteria of encephalitis (of any cause) rely on the demonstration of decreased level of consciousness, neuroimaging findings suggesting inflammation, and CSF pleocytosis. In contrast, the recently proposed criteria of AE are less restrictive and do not require evidence of CNS inflammation.1 Our current findings confirm that these criteria are appropriate to identify as having possible AE those patients without evidence of CNS inflammation.

Only 1 of 4 patients with DPPX antibodies in the current series had normal MRI and CSF studies. In a previous study of 20 patients9 whose data were not uniformly available, 7 (35%) had age ≥60 years, 7 of 10 had normal CSF, and 0 of 13 had MRI features of encephalitis, suggesting that patients with this disorder may be prone to present without CNS inflammatory abnormalities.

Our findings do not support the common believe that in the elderly rapidly progressive dementia is a frequent clinical presentation of disorders mediated by antibodies against neuronal surface antigens.6 We believe that this low frequency of cases in our series is not due to selection bias because our laboratory is a reference center for patients with suspected prion dementia and the frequency of patients with antibodies against neuronal surface antigens in those patients is <2%.10 On the other hand, we acknowledge a selection bias of patients with IgLON5 antibodies probably due to our original description of the disorder and the limited accessibility to commercial diagnostic tests.2

Overall, our findings suggest that physicians should be aware of the occurrence of immune-mediated CNS disorders without signs of brain inflammation in MRI and CSF studies. Some clinical manifestations such as FBDS, anti-IgLON5 syndrome, or rapidly progressive symptoms compatible with AE often suggest the diagnosis. Despite this, the diagnosis is challenging for a small proportion of patients with predominant cognitive decline. In these cases, additional clues such as gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea) or unexplained progressive sleep dysfunction may suggest an autoimmune case, which can be assessed with autoantibody testing.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AE

autoimmune encephalitis

- FBDS

faciobrachial dystonic seizures

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Escudero, Dalmau, Graus. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Escudero, Guasp, Dalmau, Graus. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Obtained funding: Graus, Dalmau. Study supervision: Dalmau, Graus.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was supported in part by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, FEDER, Spain (FIS 15/00377, F.G.; FIS 14/00203, J.D.), Instituto de Salud Carlos III CD14/00155 (E.M.-H.), Centros de Investigación Biomédica en Red de enfermedades raras (E.M.-H., J.D.) NIH RO1NS077851 (J.D.), and Fundació Cellex (J.D.).

DISCLOSURE

D. Escudero, M. Guasp, H. Ariño, C. Gaig, and E. Martínez-Hernández reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Dalmau receives royalties from Athena Diagnostics for the use of Ma2 as an autoantibody test and from Euroimmun for the use of NMDA, GABAB receptor, GABAA receptor, DPPX, and IgLON5 as autoantibody tests; he has received an unrestricted research grant from Euroimmun. F. Graus received a licensing fee from Euroimmun for the use of IgLON5 as an autoantibody test. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaig C, Graus F, Compta Y, et al. Clinical manifestations of the anti-IgLON5 disease. Neurology 2017;88:1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irani SR, Stagg CJ, Schott JM, et al. Faciobrachial dystonic seizures: the influence of immunotherapy on seizure control and prevention of cognitive impairment in a broadening phenotype. Brain 2013;136:3151–3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, Sejvar JJ, Miller BL. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol 2008;64:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan EP, Kotsenas AL, Britton JW, et al. Basal ganglia T1 hyperintensity in LGI1-autoantibody faciobrachial dystonic seizures. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2:e161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Sonderen A, Thijs RD, Coenders EC, et al. Anti-LGI1 encephalitis: clinical syndrome and long-term follow-up. Neurology 2016;87:1449–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haitao R, Yingmai Y, Yan H, et al. Chorea and parkinsonism associated with autoantibodies to IgLON5 and responsive to immunotherapy. J Neuroimmunol 2016;300:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobin WO, Lennon VA, Komorowski L, et al. DPPX potassium channel antibody: frequency, clinical accompaniments, and outcomes in 20 patients. Neurology 2014;83:1797–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grau-Rivera O, Sánchez-Valle R, Saiz A, et al. Determination of neuronal antibodies in suspected and definite Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:74–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.