Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from computed tomography (FFRCT) predicts coronary revascularization and outcomes and whether its addition improves efficiency of referral to invasive coronary angiography (ICA) after coronary CT angiography (CTA).

Background

FFRCT may improve the efficiency of an anatomic CTA strategy for stable chest pain.

Methods

Observational cohort study of patients with stable chest pain enrolled in the PROMISE trial referred to ICA within 90 days after CTA. FFRCT was measured at a blinded core lab, and FFRCT results were unavailable to caregivers. We determined the agreement of FFRCT (positive if ≤0.80) with stenosis on CTA and ICA (positive if ≥50% left main or ≥70% other coronary artery), and predictive value for a composite of coronary revascularization or MACE (death, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina). We retrospectively assessed whether adding FFRCT ≤0.80 as a gatekeeper could improve efficiency of referral to ICA, defined as decreased rate of ICA without ≥50% stenosis and increased ICA leading to revascularization.

Results

FFRCT was calculated in 67% (181/271) of eligible patients (mean age 62 years, 36% women). FFRCT was discordant with stenosis in 31% (57/181) for CTA and 29% (52/181) for ICA. Most patients undergoing coronary revascularization had FFRCT ≤0.80 (91%, 80/88). FFRCT ≤0.80 was a significantly better predictor for revascularization or MACE than severe CTA stenosis (HR 4.3 [95% CI 2.4–8.9] versus 2.9 [1.8–5.1]; p=0.033). Reserving ICA for patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 could decrease ICA without ≥50% stenosis by 44%, and increase the proportion of ICA leading to revascularization by 24%.

Conclusion

In this hypothesis-generating study of patients with stable chest pain referred to ICA from CTA, FFRCT ≤0.80 was a better predictor of revascularization or MACE than severe stenosis on CTA. Adding FFRCT may improve efficiency of referral to ICA from CTA alone.

Keywords: fractional flow reserve, computational fluid dynamics, coronary computed tomography angiography, coronary angiography, coronary artery disease

More than 4 million Americans with stable chest pain undergo noninvasive diagnostic testing for suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) annually (1). Most have functional testing, which may lead to referral to invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and coronary revascularization. Coronary CT angiography (CTA) has emerged as an alternative whose strength is the accurate exclusion of significant coronary artery stenosis (negative predictive value: 97 to 99%). However, CTA has limited positive predictive value (64 to 86%), and so management of patients with stenosis on CTA is challenging (2,3). Furthermore, anatomic stenosis on CTA and ICA is often discordant with measures of hemodynamic significance such as invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) (4,5). The importance of the latter to improve clinical outcomes has been demonstrated in randomized comparisons of invasive FFR-guided versus stenosis-guided coronary revascularization (6,7).

Emerging computational fluid dynamics modeling techniques allow calculation of FFR noninvasively from standard CTA images (FFRCT) (8). FFRCT correlates well (r = 0.82) with invasive FFR, with a per-patient sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 79% for invasive FFR ≤0.80 indicating ischemia (9). The Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), a pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial of coronary CTA in patients with stable chest pain, provides an opportunity to test the potential impact of adding FFRCT to CTA as a gatekeeper to ICA against observed anatomic CTA-guided care. This PROMISE FFRCT substudy assessed patients referred to ICA from CTA to determine the association of a positive FFRCT ≤0.80 with coronary revascularization or MACE, to assess the agreement of FFRCT with significant stenosis on CTA and ICA, and to predict whether the addition of FFRCT to the CT-guided practice patterns observed in PROMISE could improve efficiency of an anatomic CTA strategy.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective observational cohort study was nested in PROMISE, a pragmatic North American multicenter comparative effectiveness trial that randomized patients with stable chest pain and without known CAD to anatomic coronary CTA versus functional testing between July 2010 and September 2013. The PROMISE trial has been described in detail elsewhere (10). For this study we included the subgroup randomized to CTA who subsequently underwent ICA as part of clinical care in the 90 days following CTA. Demographics and traditional cardiovascular risk factors were documented at enrollment. Institutional review board approval was obtained with waiver of informed consent.

CTA

Electrocardiogram-gated CTA had been performed on CT scanners with at least 64 detector rows (10). “Advanced” scanners were defined as each manufacturer’s most advanced model available during the trial (General Electric HD 750, Phillips Brilliance iCT, Siemens SOMATOM Definition Flash, Toshiba Aquilion One). CTA was interpreted for stenosis by local physicians who made all clinical decisions. Severe stenosis, defined as an anatomic stenosis of ≥50% in the left main or ≥70% in other major epicardial coronary arteries, constituted a per-patient “positive” CTA result.

ICA

Subjects were referred to ICA by local physicians based on the results of CTA and other clinical characteristics. ICA had been performed according to standard practice (11) and interpreted for stenosis by local physicians who made all clinical decisions, including whether to pursue revascularization. As with CTA, a severe stenosis constituted a per-patient “positive” ICA result.

Coronary revascularization and MACE

The primary endpoint was a composite of revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE: death, nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI] or hospitalization for unstable angina). All subjects had at least 12 months of follow-up. A blinded independent clinical events committee had adjudicated all events.

Eligibility for FFRCT

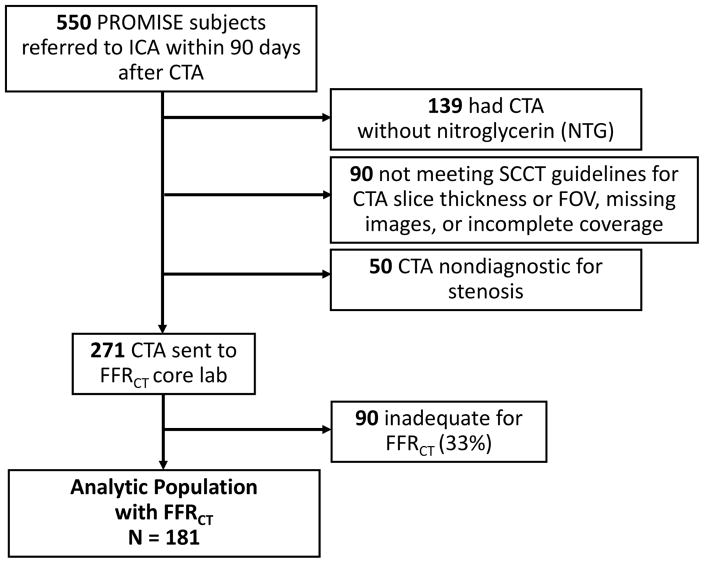

Prospectively established exclusion criteria included CTA performed without nitroglycerin, image reconstructions not compliant with Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) guidelines for pixel resolution (field of view >250mm or slice thickness ≥1mm) (12), missing images, incomplete coverage of the heart or coronary arteries, or image quality graded nondiagnostic for stenosis by a single cardiac radiologist (MTL) (Figure 1). CTA performed without nitroglycerin was excluded, based on data suggesting that FFRCT has better accuracy against invasive FFR when systemic nitrates are given (13).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

The analytic population included 181 subjects who had CTA, ICA, and FFRCT.

Computation of FFRCT from CTA

The FFRCT implementation employed in this study is computationally intensive and currently only available at a single core lab (HeartFlow, Redwood City, California) as a “send off” test (8). CTA datasets meeting eligibility criteria were sent to the FFRCT core lab. As previously validated in the NXT trial, the FFRCT core lab applied a second set of quantitative criteria to determine whether there was adequate image quality for FFRCT analysis based on whether the coronary artery lumen and myocardial boundaries could be clearly defined (9).

FFRCT was calculated blinded to all aspects of clinical care including CTA interpretation and clinical outcomes. The results of FFRCT were not available to care providers and did not affect clinical management. Techniques for calculation of FFRCT have been detailed (8) and accuracy against invasive FFR validated (9) elsewhere. Briefly, 3-dimensional models of the coronary arterial tree and myocardium were segmented from the standard CTA images used for diagnosis in the trial. Computational fluid dynamics techniques modeled coronary arterial flow under simulated maximal hyperemia. FFRCT was calculated as the ratio of mean simulated pressure to aortic pressure at all coronary artery locations measuring ≥1.8 mm. Occluded vessels were assigned a value of 0.5. The lowest per-patient FFRCT value is reported; a FFRCT ≤0.80 constituted a per-patient “positive” result.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between the analytic group who had FFRCT versus the excluded group who did not and between those with FFRCT ≤0.80 versus >0.80 were performed with the Wilcoxon 2-sample test/Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The primary study objective was to determine whether the addition of a positive FFRCT ≤0.80 was more strongly associated with the composite outcome of coronary revascularization or MACE than an anatomic-only finding of severe stenosis on CTA. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the relationship of a positive FFRCT or positive CTA compared to a negative test result for the time to the first clinical event (or censoring) for the composite endpoint (14). Relative risks were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals derived from Cox models; hazard ratios for a positive FFRCT versus positive CTA were compared with the chi-square test.

To project whether the addition of FFRCT to the observed anatomical CTA strategy could improve the efficiency of referral to ICA from CTA, we prospectively defined an FFRCT-guided decision rule that reserved ICA for patients with FFRCT ≤0.80. The projected numbers of patients having ICA, ICA without ≥50% stenosis, and ICA leading to revascularization were described in comparison to what was observed in the trial. To determine the agreement of FFRCT results with CTA and ICA findings of coronary artery stenosis, angiographic lesion severity per category and respective FFRCT values were plotted in box-and-whisker plots. The proportion of subjects having FFRCT ≤0.80 across stenosis strata on ICA and CTA were compared using the chi-square test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4) and JMP Pro (version 12) from SAS Institute (Cary, North Carolina) with a two-sided level of significance of 0.05.

Results

Study population

Of the 609 patients who were randomized to the CTA arm of PROMISE and had ICA, 59 (9.7%) either did not have CT as their first diagnostic test, had ICA >90 days after CT, or had a non-contrast CT for calcium score only (no CTA). Of the remaining 550 patients, we excluded 139 (25%) because they did not receive nitroglycerin during CTA; 90 (16%) due to missing images, incomplete coverage of the heart, or CTA image reconstruction with field of view >250mm or slice thickness ≥1mm; and 50 (9%) whose CT images were nondiagnostic for the assessment of stenosis (Figure 1). Of the 271 patients (49%) who met prospectively defined inclusion criteria, 90 (33%) were inadequate for FFRCT analysis. Thus, the analytic study population consisted of 181 patients who had complete information on CTA, ICA, and FFRCT.

The average age was 62 years, 36% (66/181) were women, and 76% were at intermediate risk for obstructive CAD by the combined Diamond and Forrester and Coronary Artery Surgery Study risk score (Table 1) (15). Compared to those who did not have FFRCT (n=369), the analytic population who had FFRCT was less likely to be obese (34% versus 53%, p<0.001), consistent with the adverse effect of obesity on CT image quality. However, both groups had a similar burden of CAD, incident revascularization, and MACE (Supplemental Table 1). The 181 subjects were enrolled at 69 North American sites (mean: 2.6 per site). Coronary CTA datasets were acquired from all 4 major CT vendors (44% [80/181] General Electric, 11% [20/181] Phillips, 36% [66/181] Siemens, and 8% [15/181] Toshiba). Advanced CT scanners were used in 17% (31/181) of the CTAs evaluated with FFRCT compared to 12% (43/369, p for comparison=0.08) of the CTAs not evaluated with FFRCT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PROMISE FFRCT participants referred to ICA after CTA, according to FFRCT ≤0.80 or >0.80

| FFRCT ≤0.80 N = 131 |

FFRCT >0.80 N = 50 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age — mean ± SD, yr | 61.6 ± 8.1 | 62.5 ± 9.8 | 0.79 |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 42 (32%) | 24 (48%) | 0.046 |

| Racial/ethnic minority — no. (%) | 11 (8.5%) | 7 (14%) | 0.28 |

| Cardiac Risk factors – no. (%) | |||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 42 (31%) | 20 (40%) | 0.27 |

| Hypertension | 83 (63%) | 31 (62%) | 0.87 |

| Diabetes | 25 (19%) | 7 (14%) | 0.42 |

| Dyslipidemia | 91 (70%) | 31 (62%) | 0.34 |

| Family history premature CAD | 58 (45%) | 26 (52%) | 0.17 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1.0 |

| CAD equivalent | 28 (21%) | 13 (26%) | 0.51 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 39 (30%) | 13 (26%) | 0.62 |

| Smoking history | 77 (59%) | 24 (78%) | 0.17 |

| Combined Diamond and Forrester and CASS | 0.066 | ||

| Low (<25%) | 7 (5.3%) | 6 (12.0%) | |

| Intermediate (25–75%) | 98 (75%) | 40 (80%) | |

| High (>75%) | 26 (20%) | 4 (8.0%) | |

| CTA radiation dose — mean ± SD, mSv | 9.8 ± 6.4 | 9.8 ± 6.1 | 0.99 |

BMI = body mass index; CAD = coronary artery disease; CASS = Coronary Artery Surgery Study; CTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; FFRCT = noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from CTA; ICA = invasive coronary angiography.

CTA and ICA stenosis

Most patients had severe (≥70% or ≥50% left main) stenosis on coronary CTA (66%, 120/181) and ICA (54%, 97/181) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stenosis, revascularization, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by FFRCT ≤0.80

| FFRCT ≤0.80 N = 131 |

FFRCT >0.80 N = 50 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTA stenosis – no. (%) | 0.002 | ||

| Mild (<50%) | 8 (6%) | 9 (18%) | |

| Moderate (50–69%) | 26 (20%) | 18 (36%) | |

| Severe (≥70% or ≥50% left main) | 97 (74%) | 23 (46%) | |

| Left main | 11 (8%) | 3 (6%) | 0.76 |

| One vessel | 65 (50%) | 17 (34%) | 0.004 |

| Two vessel | 24 (18%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Three vessel | 8 (6%) | 2 (4%) | |

| ICA stenosis — no. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Mild (<50%) | 20 (15%) | 29 (58%) | |

| Moderate (50–69%) | 23 (18%) | 12 (24%) | |

| Severe (≥70% or ≥50% left main) | 88 (67%) | 9 (18%) | |

| Left main | 9 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.065 |

| Single vessel | 57 (44%) | 8 (16%) | <0.001 |

| Two vessel | 17 (13%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Three vessel | 14 (11%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Revascularization — no. (%) | 80 (61%) | 8 (16%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 67 (51%) | 8 (16%) | |

| CABG | 13 (10%) | 0 | |

| MACE — no. (%) | 14 (11%) | 2* (4%) | 0.24 |

| Death | 1 (0.8%) | 0 | |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Hospitalization for unstable angina | 12 (9%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Composite of Revascularization or MACE — no. (%) | 83 (63%) | 10 (20%) | <0.001 |

Both patients with an event and FFRCT >0.80 did not have severe stenosis on ICA and were not revascularized.

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Coronary revascularization and MACE

During median follow-up of 29 months (IQR 18.9–36.3 months) the primary outcome of a composite of coronary revascularization or MACE occurred in 51% (93/181, Table 2). Overall, 49% (88/181) had coronary revascularization, including 75 PCI and 13 CABG. MACE occurred in 9% (16/181), including 1 death, 2 nonfatal MIs, and 13 hospitalizations for unstable angina.

FFRCT measurements

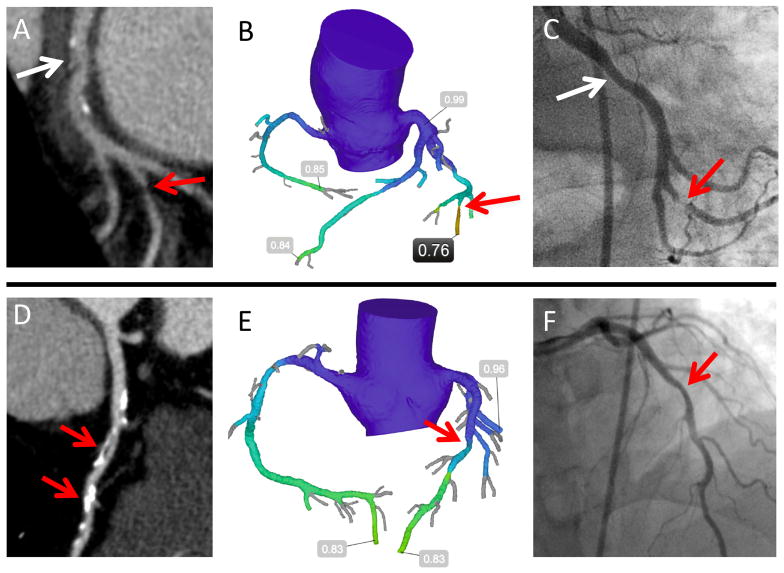

With per-patient FFRCT defined as the lowest FFRCT value for that patient, mean per-patient FFRCT was 0.71±0.13, with 72% (131/181) of patients having a FFRCT ≤0.80. Patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 were less likely to be women (32% versus 48%, p=0.046) but had otherwise similar demographics and risk factors compared to those with FFRCT >0.80 (Table 1). Two representative cases are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Representative CTA, FFRCT, and ICA.

The first patient (A–C) was referred to ICA based on (A) CTA moderate stenosis in the left circumflex (white arrow). Severe stenosis in an obtuse marginal (red arrow) was missed by the CT reader, but detected by (B) FFRCT of 0.76 and confirmed on (C) ICA showing severe stenosis, with subsequent PCI. Circumflex stenosis (white arrow) was mild and not revascularized. The second patient (D–F) was referred to ICA for (D) severe mid left anterior descending stenoses on CTA (red arrows). (E) FFRCT of 0.83 suggests no hemodynamically significant stenosis; (F) ICA demonstrated mild stenosis that was not revascularized.

Agreement of FFRCT with CTA and ICA

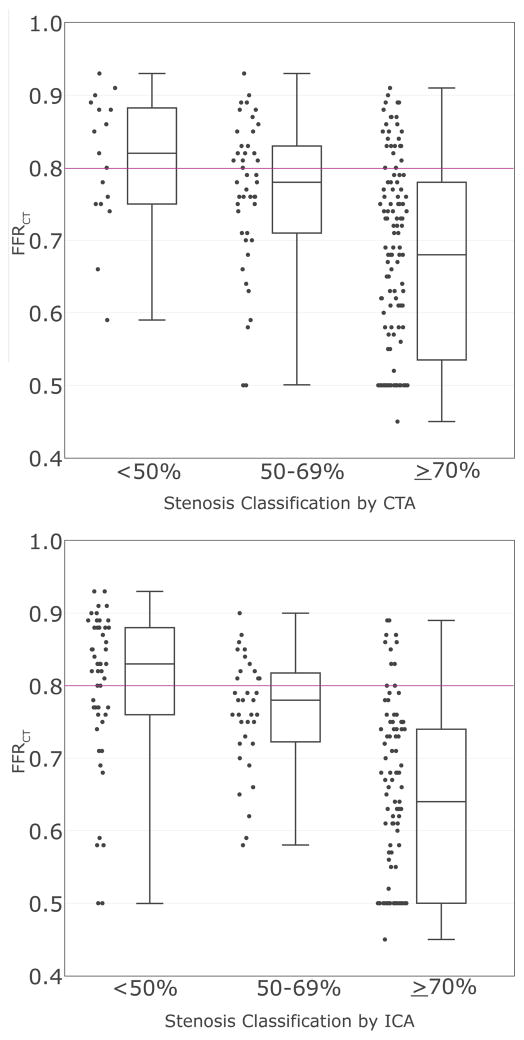

Compared to the degree of stenosis on CTA (worst per patient), mean FFRCT (lowest per patient) decreased from 0.81±0.09 for mild stenosis (<50%) to 0.77±0.10 for moderate stenosis (50–69%) to 0.67±0.13 for severe stenosis (p<0.001). Similar results were seen for ICA (0.80±0.11, 0.75±0.08, and 0.64 ±0.12, respectively; p <0.001) (Figure 3). There was agreement between FFRCT and CTA in 69% (124/181) of patients, among them 54% (97/181) with positive FFRCT ≤0.80 who had severe CTA stenosis and 15% (27/181) with negative FFRCT who had less than severe CTA stenosis (Table 2). A similar agreement rate of 71% (129/181) was seen between FFRCT ≤0.80 and severe ICA stenosis. The disagreement rates with FFRCT were 31% (57/181) for CTA and 29% (52/181) for ICA.

Figure 3. Box and Whisker Plots of Per-Patient FFRCT by Categories of (A) CTA and (B) ICA Stenosis.

The horizontal line corresponds to the FFRCT threshold for a positive test (FFRCT ≤0.80). FFRCT decreased with increasing degrees of stenosis on CTA and ICA (both p<0.001).

Association of FFRCT with coronary revascularization and MACE

Patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 were significantly more likely to have coronary revascularization (61%, 80/131 versus 16%, 8/50, hazard ratio (HR) 5.13 [95% CI 2.63–11.53; p<0.001] [Table 2]). There was a trend toward more patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 experiencing a MACE (11%, 14/131 versus 4%, 2/50, HR 2.67 [95% CI 0.75–17.02; p=0.14]). There were 2 MACE events (one nonfatal MI and one hospitalization for unstable angina) with FFRCT >0.80, both in patients with <70% stenosis on ICA who did not undergo coronary revascularization.

FFRCT ≤0.80 was significantly associated with the composite endpoint of MACE or revascularization compared to those with FFRCT >0.80 (63%, 83/131 versus 20%, 10/50, HR 4.31 [95% CI 2.35–8.88; p<0.001]). Severe stenosis on CTA was also significantly associated with the composite endpoint compared to lesser stenosis (63%, 76/120 versus 28%, 17/61, HR 2.90 [95% CI 1.76–5.10]; p<0.001]. However, FFRCT ≤0.80 was significantly better than severe CTA stenosis at predicting the composite endpoint (HR 4.31 for FFRCT versus 2.90 for CTA stenosis; p=0.033). This is notable as FFRCT results were not available to physicians during the trial while the CTA results guided management.

Potential improvement in efficiency of referral to ICA by adding FFRCT

Reserving ICA for patients with a positive FFRCT (≤0.80) could reduce the number of ICA following CTA by 28% (50/181), decrease the rate of ICA without ≥50% stenosis by 44% (from 27% [49/181] to 15% [20/131]), and increase the rate of ICA leading to revascularization by 24% (from 49% [88/181] to 61% [80/131]). On the other hand, this rule would result in 9% fewer (8/88) coronary revascularizations (8 PCI, 0 CABG); the impact of which cannot be estimated in this study. On ICA, 6 of these patients had PCI of severe single-vessel stenosis (none involving the left main or proximal left anterior descending coronary arteries), and 2 had PCI of moderate (50 to 69%) proximal left anterior descending stenoses. Notably, none of these patients experienced a MACE.

In a sensitivity analysis, we recalculated these figures including the 90 patients whose images were sent to the FFRCT core lab but were inadequate for FFRCT analysis. Assuming a worst case that all 90 proceeded to ICA, we estimate a lesser reduction in the rate of ICA by 18% (50/271), decrease in the rate of ICA without ≥50% stenosis by 20% (from 31% [84/271] to 25% [55/221]), and increase in the rate of ICA leading to revascularization by 15% (from 49% [134/271] to 57% [126/221]).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the potential impact of adding noninvasively calculated FFRCT to an anatomic CTA strategy for evaluation of stable chest pain. In patients referred to ICA after CTA, we demonstrate that retrospectively obtained FFRCT has better predictive value for the composite outcome of coronary revascularization or MACE than severe (≥70%) stenosis on CTA. Furthermore, our data suggest that adding information on FFRCT to coronary CTA may improve the efficiency of referral to ICA by lowering the number of invasive angiograms, decreasing the proportion of ICA without ≥50% stenosis, and increasing the rate of subsequent coronary revascularization.

We demonstrate that noninvasive FFRCT values decrease with increasing luminal stenosis, but also that there is substantial disagreement between anatomic significance (severe stenosis) and hemodynamic significance (FFRCT ≤0.80) for both CTA (31%) and ICA (29%), similar to the 25% discrepancy rate between invasive FFR and ICA found in the FAME trial (4). In addition, patients with FFRCT ≤0.80 were substantially more likely to suffer revascularization or MACE compared to those with FFRCT >0.80 (HR 4.31, p<0.001). While the prognostic value of FFR has been shown in invasive studies such as DEFER (16) and FAME (7), it has not been previously reported for noninvasive FFRCT in an observational setting where FFRCT did not alter clinical management. Moreover, the association of FFRCT with revascularization and MACE was significantly stronger than for severe stenosis on CTA (HR 4.31 versus 2.90, p=0.033), a notable result as stenosis guided the clinical decision for coronary revascularization, whereas FFRCT was not available to caregivers in the trial.

Multicenter trials of CTA in patients with acute (17,18) and stable chest pain (10) suggest that CTA leads to greater referral to ICA compared to usual care. In PROMISE, patients in the CTA arm had 51% more ICA than those in the functional arm (12.2% versus 8.1%). Our results suggest that adding FFRCT to anatomic CTA, with a positive FFRCT ≤0.80 as a criterion for referral to ICA, may address this by reducing referral to ICA from CTA by up to 28%. Extrapolation to all 550 patients in PROMISE who underwent ICA as part of the anatomic CTA strategy should be interpreted with caution, but could decrease the rate of referral to ICA in the anatomic arm from 12.2% to 9.5%, which is more comparable to the ICA rate of 8.1% observed in the functional testing arm (10). Furthermore, adding FFRCT to CTA could increase the proportion of ICA leading to coronary revascularization from 49% to 61%. Such projections may be justified as the burden of CAD and coronary revascularization were similar between the 181 patients in whom we measured FFRCT and the 369 patients who were also referred for ICA but did not have FFRCT (Supplemental Table 1).

Our study included PROMISE patients with stable chest pain referred to ICA after CTA. Thus FFRCT was not assessed in isolation, but in the context of CTA findings that prompted referral to ICA. We did not include patients whose CTA results did not prompt referral to ICA, and so our results do not address use of FFRCT in this broader group. Our findings suggesting that the addition of FFRCT could be incremental to anatomic CTA as a gatekeeper to ICA within a North American trial support and expand on a recent European cohort study (PLATFORM: Prospective LongitudinAl Trial of FFRCT Outcome and Resource IMpacts) of patients with planned ICA, which reported that combined CTA/FFRCT led to a very low (12%) rate of ICA without ≥50% stenosis and a high rate of ICA leading to revascularization (72%), similar to the rates we found by adding FFRCT to CTA in PROMISE (15% and 61%, respectively) (19). The similarity of these numbers are remarkable as all of our patients were referred to ICA from CTA, whereas this was not the case in PLATFORM.

In our study, 91% (80/88) of coronary revascularizations had a positive FFRCT. This mirrors FAME, which found that 90% of patients considered for stenosis-guided revascularization had a positive invasive FFR (7). The sound agreement of positive FFRCT with observed clinical decisions to pursue revascularization in PROMISE is notable, as FFRCT was measured independent of clinical care and not available to caregivers. This finding is also important as in PROMISE nearly all revascularization decisions were made without the guidance of invasive FFR, which reflected practice in the community at that time (20). Although there was no significant difference in outcomes between CTA and functional arms of PROMISE, our data provide some reassurance that most coronary revascularizations were likely performed in hemodynamically significant lesions.

Limitations of the data and FFRCT technique should be considered. One-half of patients referred to ICA from CTA were excluded by prespecified entry criteria, mostly because they did not follow SCCT guidelines for standard CTA including administration of nitroglycerin and high image pixel resolution (12). Guidelines recommend nitroglycerin and high resolution images for standard coronary CTA as they aid the diagnosis of stenosis; they are also necessary for FFRCT as they provide a better approximation of the vessel anatomy under maximal hyperemia (13,21). Presumably more sites would have followed these now standard practices had they known that FFRCT would be performed. Furthermore, CT technology has advanced rapidly since PROMISE, and the data likely do not represent the current state of the art. In PROMISE, most CTA was performed on standard 64-slice CT scanners, with only 17% using advanced CT scanners that have since been succeeded by a new generation of CT equipment.

FFRCT has different image quality requirements than traditional assessment for stenosis. When confronted with motion artifact, physicians interpreting CTA for stenosis often integrate multiple cardiac phases to piece together a complete coronary artery. In contrast, the current implementation of FFRCT requires that the entire coronary tree and myocardium be evaluable on a single cardiac phase. A third (33%) of the CTAs sent to the FFRCT core lab were inadequate for FFRCT analysis — this is higher than reported in dedicated FFRCT trials such as NXT (13% inadequate, 10 European and Asian sites) and PLATFORM (12% inadequate, 11 European sites) (9,19). This may be explained by the fact that NXT and PLATFORM were dedicated FFRCT studies, with sites receiving specific FFRCT training and feedback including standard administration of nitroglycerin and appropriate image reconstruction. In contrast, PROMISE sites did not know that FFRCT would be performed and did not receive specific FFRCT training or feedback.

In this observational study, the results of FFRCT were not available to caregivers and did not affect clinical decision making. We can only project how physicians would have used the FFRCT results had they been available. Six patients had PCI with a FFRCT >0.80. Previous trials found that FFRCT has good accuracy compared to invasive FFR and that revascularization can be safely deferred with a FFRCT >0.80, but due to the observational design we cannot know for certain what would have happened in these 6 patients. A final limitation is the small sample size and low number of outcomes in keeping with the low event rate in the PROMISE trial. Hospitalization for unstable angina was the most common adverse event and had the potential for bias, as it may have been triggered by the knowledge that CAD was present on CTA.

Conclusions

In this hypothesis-generating study of patients with stable chest pain referred to ICA after CTA, we found that adding FFRCT may improve the efficiency of referral to ICA, addressing a major concern of an anatomic CTA strategy. FFRCT has incremental value over anatomic CTA in predicting revascularization or major adverse cardiovascular events.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

Competency in Medical Knowledge

Fractional flow reserve derived noninvasively from coronary CTA (FFRCT) can assess the functional importance of coronary lesions.

Competency in Patient Care and Procedural Skills

Guidelines recommend determining the functional significance of coronary lesions prior to revascularization.

Translational Outlook

CT substudy data suggest that FFRCT is associated with observed revascularization and MACE. The addition of FFRCT to CTA has the potential to improve efficiency of management of patients with stable chest pain who are referred to ICA after CTA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Souma Sengupta and Dr. Campbell Rogers (HeartFlow) for calculation of FFRCT, as well as the PROMISE participants, staff, and investigators for their contributions to the trial.

Abbreviations

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- FFR

invasive fractional flow reserve measured during ICA

- FFRCT

noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from CTA

- ICA

invasive coronary angiography

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- PLATFORM

Prospective LongitudinAL Trial of FFRCT: Outcome and Resource Impacts

- PROMISE

PROspective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain

Footnotes

Funding and Disclosures: This work was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from HeartFlow, Inc, Redwood City, CA. The parent PROMISE trial was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL098237, R01HL098236, R01HL098305, and R01HL098235. Dr. Lu’s effort was supported by the American Roentgen Ray Society Scholarship. Dr. Ferencik’s effort was supported by the American Heart Association Fellow to Faculty Award. Dr. Mark has received grant support from Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, AGA Medical, Merck, Oxygen Biotherapeutics, and AstraZeneca as well as personal fees from Medtronic, CardioDx, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Jaffer has received grant support from Siemens and Canon USA, and is a consultant for Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. Dr. Leipsic is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences, Samsung, Philips, Pi-Cardia, Circle CVI, GE Healthcare, and HeartFlow. Dr. Douglas has received grants from HeartFlow and GE HealthCare. Dr. Hoffmann has received grants from HeartFlow and Siemens Healthcare and in addition is a consultant to HeartFlow. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, data analysis, or decision to submit the manuscript. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of HeartFlow or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ladapo JA, Blecker S, Douglas PS. Physician decision making and trends in the use of cardiac stress testing in the United States: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:482–90. doi: 10.7326/M14-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonino PA, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2816–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budoff MJ, Nakazato R, Mancini GB, et al. CT Angiography for the Prediction of Hemodynamic Significance in Intermediate and Severe Lesions: Head-to-Head Comparison With Quantitative Coronary Angiography Using Fractional Flow Reserve as the Reference Standard. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1208–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min JK, Taylor CA, Achenbach S, et al. Noninvasive Fractional Flow Reserve Derived From Coronary CT Angiography: Clinical Data and Scientific Principles. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2015;8:1209–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S, et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291–300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naidu SS, Rao SV, Blankenship J, et al. Clinical expert consensus statement on best practices in the cardiac catheterization laboratory: Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:456–64. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ, et al. SCCT guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:190–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leipsic J, Yang TH, Thompson A, et al. CT angiography (CTA) and diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve: results from the Determination of Fractional Flow Reserve by Anatomic CTA (DeFACTO) study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:989–94. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44–e164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pijls NH, van Schaardenburgh P, Manoharan G, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention of functionally nonsignificant stenosis: 5-year follow-up of the DEFER Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:299–308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, et al. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas PS, Pontone G, Hlatky MA, et al. Clinical outcomes of fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography-guided diagnostic strategies vs. usual care in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the prospective longitudinal trial of FFRct: outcome and resource impacts study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3368–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dattilo PB, Prasad A, Honeycutt E, Wang TY, Messenger JC. Contemporary patterns of fractional flow reserve and intravascular ultrasound use among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: Insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2337–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takx RA, Sucha D, Park J, Leiner T, Hoffmann U. Sublingual Nitroglycerin Administration in Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography: a Systematic Review. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:3536–42. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3791-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.