Abstract

Purpose

Monitoring blood loss is important for management of surgical patients. This study reviews a device (Triton) that uses computer analysis of a photograph to estimate hemoglobin (Hb) mass present on surgical sponges. The device essentially does what a clinician does when trying to make a visual estimation of blood loss by looking at a sponge, albeit with less subjective variation. The performance of the Triton system is reported upon in during real-time use in surgical procedures.

Methods

The cumulative Hb losses estimated using the Triton system for 50 enrolled patients were compared with reference Hb measurements during the first quarter, half, three-quarters and full duration of the surgery. Additionally, the estimated blood loss (EBL) was calculated using the Triton measured Hb loss and compared with values obtained from both visual estimation and gravimetric measurements.

Results

Hb loss measured by Triton correlated with the reference method across the four measurement intervals. Bias remained low and increased from 0.1 g in the first quarter to 3.7 g at the case completion. The limits of agreement remained narrow and increased proportionally from the beginning to the end of the cases, reaching a maximum range of −15.3 g to 22.7 g. The median (IQR) difference of EBL derived from the Triton system, gravimetric method and visual estimation versus the reference value were 13 (74), 389 (287), and 4 (230) mL, respectively.

Conclusion

Use of the Triton system to measure Hb loss in real-time during surgery is feasible and accurate.

Keywords: Hemoglobin loss, intraoperative blood loss, gravimetric method, sponge blood estimation

INTRODUCTION

Accurate assessment of blood loss is an important aspect of surgical patient management. Blood loss is routinely assessed by visual estimation of the amount of blood in suction canisters, surgical sponges and surgical drapes, making it highly subjective with poor precision and accuracy [2–5].

The Triton system (Gauss Surgical, Inc., Los Altos, CA) is an FDA-cleared mobile application on an iPad tablet computer (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA). It uses the enabled tablet camera to capture images of surgical sponges, then uses image analysis algorithms and cloud-based machine learning to accurately estimate hemoglobin (Hb) mass on the surgical laparotomy sponges in real time. The performance of the device has been validated in bench-top and postoperative settings [7,8].

Here, the performance of the Triton system and its accuracy measuring Hb mass and blood loss from surgical sponges in real time is reported upon during a wide variety of surgical procedures. It was hypothesized that there would not be a clinically significant difference between the Triton measurement and the reference measurement of blood loss which was performed through the rinsing of sponges and subsequent measurement of Hb in the rinse solution.

METHODS

A prospective, single-center study was performed in which surgical sponges from consecutive cases were scanned in real-time using the Triton system. To evaluate the performance of the device in procedures with varying amounts of blood loss we included general, obstetric, orthopedic and urologic procedures. Enrollment was initiated in July 2013 and continued through October 2013. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, CA).

There were no patient-specific inclusion or exclusion criteria for the study. Preoperative Hb (g/dL) was recorded for each patient. Whenever hematocrit (Hct) was available instead of Hb, Hb was determined by dividing Hct by 3. Estimated blood loss (EBL) based on visual estimation by the clinical staff was routinely done and obtained from the surgical records. The surgical staff did not have access to Triton system estimates. All procedures were performed according to the standard of care and no modifications in patient management were made for the study. Patient consent was waived by the IRB.

Hemoglobin Loss and Blood Loss Measurements

Photographs of each sponge were immediately taken as they were removed from the surgical field as part of the routine process of recording sponge count. These images were captured with the aid of a pedal for the foot wirelessly connected to the iPad via Bluetooth (Figure 1). The captured images of the sponges were then encrypted and wirelessly transferred to a remote server where Hb mass (mHbTriton) was determined using Gauss’ Feature Extraction Technology (FET). FET dissects photographic and geometric information from relevant regions of interest, then employs fine-grained detection, classification, and thresholding schemes to filter out the effects of extraneous non-sanguineous fluids (e.g., saline) and to compensate for variability in intraoperative lighting conditions [8]. A cumulative value of the mHb in sponges is returned to the mobile display within seconds.

Fig. 1.

Sponge image capture during surgery

For a reference comparison, the Hb mass on each sponge was measured by manually rinsing the sponge with saline and measuring the Hb content of the effluent (mHbRinse). The accuracy of this method has been verified using sponges stained with known amounts of blood [7]. This assay was performed outside of the operating room and completed within two hours of the end of the case. EBL for each method was calculated by dividing the measured Hb loss by the patient’s preoperative blood Hb concentration. The individual weight of each sponge was also measured using a digital scale (A&D Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) immediately after scanning with the Triton system. The known dry weight of each sponge was subtracted to yield the total fluid weight, and reported as the gravimetric estimated blood loss (EBLWeight), assuming that each gram (g) weight corresponded to 1 mL volume (i.e. similar density as water).

Surgical start and end times were recorded, as well as the time at which each sponge was scanned intraoperatively. These data were used to group all of the measurements into four cumulative time-based quartiles: the 1st group consisted of all of the sponges removed from the surgical field and scanned into the system during the first quarter of time lapsed, the second group consisted of the sponges scanned during the first half of time lapsed, the third group consisted of the sponges scanned during the first three-quarters of time lapsed, and the fourth group consisted of all of the sponges scanned during the entirety of each surgical case.

To determine the effect of the sponges drying out on the accuracy of the Triton device’s measurements, each sponge was again scanned within 2 hours after the completion of surgery and prior to performing the manual Hb mass measurement described above to allow for comparison between the intraoperative value and a value obtained within this two-hour window. All study procedures were performed by trained operating room staff with standard protective gear and in accordance with standard operating room policies and procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Variables are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (SD), median/interquartile range (IQR) or count (%) as appropriate. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate whether the continuous variables followed normal distribution. For parameter estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided. The primary outcome variable was the bias of blood loss measurement, calculated as the mean difference between the Hb mass estimated by the Triton system (mHbTriton) and the directly measured Hb mass (mHbRinse). The two measurements were evaluated using the Bland-Altman method, wherein bias (mean difference between the two measures) and upper and lower limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96×SD) with their respective 95% CIs were computed [9]. An acceptance criterion of ±30 g per case was set a priori as the clinically acceptable maximum bias, which corresponded to a blood volume of ~250 mL (roughly the volume of ½ unit of whole blood) or approximately 3–5% of total blood volume in an average adult male [7–9]. Additionally, volumetric blood loss measures of the Triton system (EBLTriton, calculated by the Triton system using the estimated Hb mass and available Hb concentration of the patient) and the gravimetric method (EBLWeight) were compared with a two-sided paired t-test. Additional analyses were performed using t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test, and Pearson or Spearman’s Correlations as appropriate.

Prior studies indicated that the SD of the Hb mass bias was relatively low (~10 g or less) compared with the acceptance criterion (30 g), therefore a sample size of 50 cases was deemed adequate as it provided a 95% CI of ±0.5×SD (approximately ±5 g) around the limits of agreement [9]. This sample size would allow 90% certainty that the limits of a two-sided 95% CI would exclude a bias of 7.25×SD if there were truly no difference between the two measurement methods [10]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 13.0, SPSS, Inc).

RESULTS

Study Population and Procedures

A total of 797 sponges were analyzed from 50 surgical procedures. The types of surgical cases, number of sponges per surgical case, and average preoperative Hb levels are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Procedure Types with Sponge Count and corresponding Preoperative Hb levels (g/dl). Values are presented as number and percent or as mean and SD.

| Procedure Type | Number of Cases | Average Sponge Count & SD | Preoperative Hb (g/dl) & SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetrics | 29 | 58% | 16 | ± 6 | 12.1 | ± 1.1 |

| Orthopedics | 6 | 12% | 13 | ± 3 | 11.5 | ± 1.5 |

| Urology | 3 | 6% | 22 | ± 10 | 12.9 | ± 3.1 |

| General Surgery | 12 | 24% | 16 | ± 6 | 11.9 | ± 2.1 |

| Total | 50 | 100% | 16.5 | ± 10.4 | 12.9 | ± 1.5 |

Comparison of Hemoglobin Loss as Measured by Device and by Rinsing Method

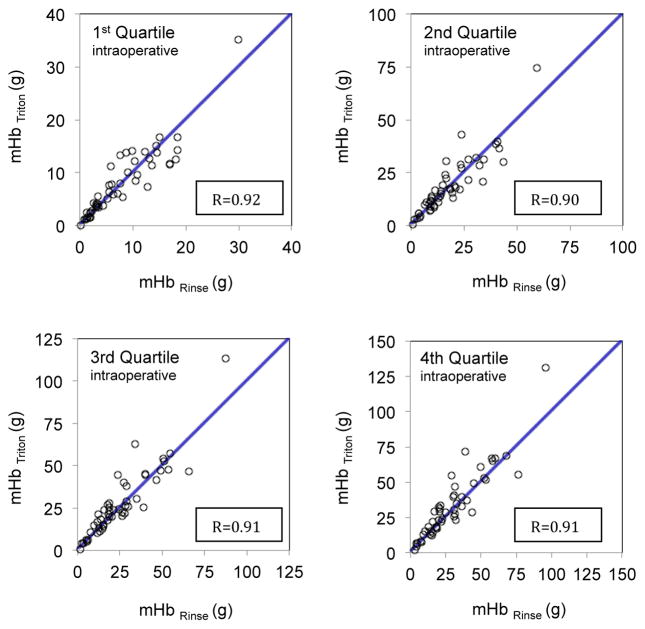

The median (IQR) Hb loss per case was 28.8 (30.9) g according to Triton system and 23.6 (23.2) g according to the rinsing method. Cumulative estimation of sponge Hb mass using the Triton System (mHbTriton) and direct measurement of Hb mass by rinsing method (mHbRinse) were correlated across all four quartiles (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the estimation of sponge Hb mass using the Triton System (mHbTriton) and direct measurement of Hb mass by rinsing (mHbRinse) across all four surgical time quartiles

Table 2.

Agreement of Hb mass as measured using the device (mHbTriton) compared with direct measurement by rinsing method (mHbRinse), across the four surgical time quartiles periods as well as at the post-operative re-scanning of sponges.

| Parameter | 1st Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile (All Sponges) | Post-operative Re-scanning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Sponge Count (SD) | 3 (1) | 7(3) | 11(4) | 16(6) | 16(6) |

| Hb Mass Range, g | 0.2 to 29.9 | 1.0 to 59.2 | 3.1 to 95.7 | 3.1 to 95.7 | 3.1 to 95.7 |

| Correlation Between the Methods (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.95) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.94) | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.95) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.95) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.95) |

| Bias (95% CI), g | 0.1 (−0.6 to 0.9) | 0.6 (−1.0 to 2.3) | 2.2 (−0.1 to 4.5) | 3.7 (1.0 to 6.5) | −0.9 (−3.3 to 1.5) |

| Lower Limit of Agreement (95% CI), g | −4.9 (−5.6 to −4.2) | −10.7 (−12.3 to −9.0) | −13.8 (−16.1 to −11.5) | −15.3 (−18.0 to −12.5) | −17.2 (−19.6 to −14.9) |

| Upper Limit of Agreement (95% CI), g | 5.2 (4.4 to 5.9) | 12 (1.3 to 13.6) | 18.2 (15.9 to 20.5) | 22.7 (20.0 to 25.5) | 15.4 (13.1 to 17.8) |

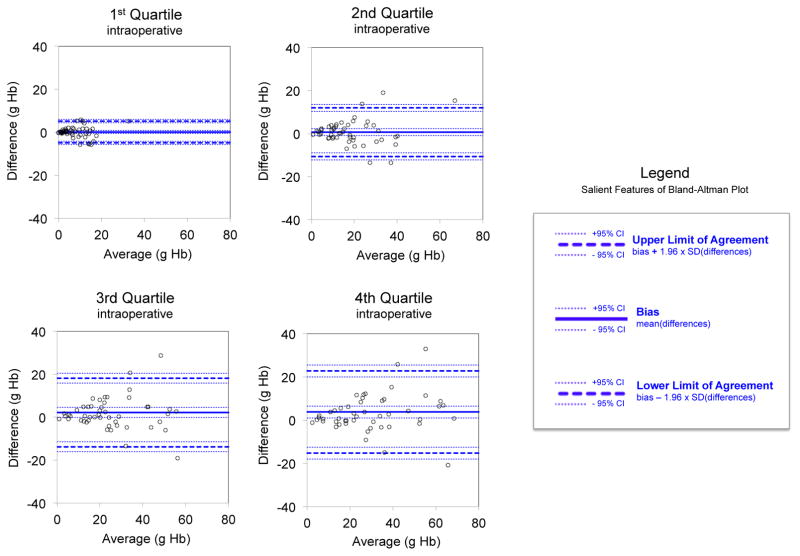

Bias of Hb mass followed a near normal distribution and was 3.73 (95% CI 0.98 to 6.49) g. The Hb mass bias was not correlated with preoperative Hb level, total sponge count per case, duration of surgery, time elapsed between the first and last sponges scanned in each case, or total fluid content of sponges for each case. There was no statistically significant correlation between the bias and mean of mHbTriton or mHbRinse (Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient 0.44, p=0.088). Figure 3 represents the assessment of agreement between the two methods across four quartiles using the Bland-Altman approach. Measures of agreement between mHbTriton and mHbRinse in various quartiles as well as the post-operative re-scanning of all sponges are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Bland and Altman plots of the agreement between the estimation of sponge Hb mass using the Triton System (mHbTriton) and direct measurement of Hb mass by rinsing (mHbRinse). Solid and dashed blue lines represent the bias and the limits of agreement, respectively. As depicted by the legend in the lower RHS, Dotted lines around the bias and the limits of agreement represent their corresponding upper and lower 95% confidence interval

Comparison of Estimated Blood Loss as Measured by the Device, by Rinsing Method, by Visual Estimation, and by Weighing of Sponges

Median EBL (IQR) values based on Triton system, rinsing method, gravimetric method and visual estimation were 247 (250), 218 (203), 565 (421), and 200 (290) mL, respectively. Visual EBL was not recorded for 6 cases and those cases were excluded only from analyses involving visual estimation of EBL. Figure 4 represents scatter plots of the direct measurement of blood loss using the rinsing method and blood loss estimated by the device, visual estimation, and the gravimetric method. EBL based on the rinsing method EBL was correlated with the EBL derived from the three other methods. On average, for each 1 mL increase in the EBL based on the rinsing method, Triton EBL increased by 1.12 mL (95% CI 1.18 to 1.59; R2=0.798), visual EBL increased by 2.54 mL (95% CI 1.62 to 5.85, R2=0.233), and gravimetric EBL increased by 2.47 mL (95% CI 2.12 to 2.95, R2=0.760).

Fig. 4.

Accuracy comparisons between the direct physical measurement of blood loss (EBLRinse) and (A) blood loss estimated by the device (EBLTriton); (B) blood loss estimated by visual estimation by the clinical staff (EBLVisual); and (C) blood loss as measured by weighing of sponges (EBLWeight)

Biases of EBL (IQR) derived from Triton system, visual estimation, and gravimetric method with the direct rinsing method as the reference value were 13 (74), 4 (230), and 389 (287) mL, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Clinicians are routinely tasked with monitoring the blood loss during surgery and the amount and rate of surgical blood loss is among the criteria recommended by guidelines to make transfusion decisions [1]. With no reliable and clinically feasible measurement method available, clinicians are often forced to rely on their visual estimation to monitor blood loss, a technique known to have low reliability and accuracy [3,4]. Some have gone as far as questioning the continued use of visual estimation of blood loss in clinical practice given the lack of accuracy [11]. Approaches such as educational interventions and aids (e.g. cards with printed standard pictures corresponding to various amounts of blood loss) have been utilized in an attempt to improve the accuracy and precision of visual estimation, but these efforts have resulted in limited success [12,13]. Gravimetric assessment of blood loss is another well-described method, however results for this technique can be inconsistent with measurements potentially affected by recording bias, amniotic fluid/saline corruption, and human error [19].

Here a clinical study of the performance of the Triton system to estimate real-time blood loss in sponges is reported in a series of 50 mixed surgical cases at a single center. Using a machine-learning algorithm and based on the extent and intensity of the blood stain on the sponge, the device estimates the amount of Hb present on each sponge [7,8]. The device essentially does what a clinician does in trying to make a visual estimation of blood loss by looking at the sponge, albeit with much more accuracy and precision and less subjective variation.

The performance of the device has been validated in several other studies. In a laboratory study performed under various lighting settings, in the presence of various potentially interfering agents, and using a variety of standard commonly used surgical sponges, the bias of measured Hb on a per-sponge basis (versus the known amount of blood added to each sponge) was 0.01 g (upper and lower limits of agreement −1.16 and 1.19 g, respectively) [8]. In a study of 46 human subjects undergoing various surgeries, surgical sponges were collected, stored, then measured postoperatively for blood loss. The bias of total Hb per case measured by the Triton system versus the reference method (manual rinsing) was 9.0 g (upper and lower limits of agreement −7.5 and 25.5 g, respectively) [7]. The present study shares many similarities with the latter human study, but with the important distinction of measurements being performed real-time in the operating room as individual sponges were being removed from the surgical field. Hence, the present study provides a more practical assessment of how the device performs in real-world clinical setting.

This study indicates that real-time use of the device by the operating room staff was feasible and yielded similarly accurate results as a previous study [7]. Analysis of Triton measurements and reference measurements accumulated during the first 25%, 50%, 75% and throughout the duration of the cases indicated that the correlation remained strong (Figure 2) and the bias remained relatively small as it increased from 0.1 g in the first quarter to 3.7 g at the completion of the case. The limits of agreement remained narrow and increased proportionally from the beginning to the end of the cases across all 4 time quartiles. Considering the mean observed preoperative Hb level of 12 g/dL, this Hb bias corresponds to a mean blood volume of approximately 31 ml. Assessment of Bland-Altman plots (Figure 3) indicated that the bias remained relatively constant throughout a wide range of Hb mass, and the limits of agreement of the Triton method and reference method (direct rinsing) stayed within the preset acceptance criterion of 30 g per case (corresponding to a blood volume of ~250 mL). Note also that scanning dried sponges 2 hours post-operatively did not significantly change the results observed immediately post-operatively (see Table 2).

Conversely, visual estimation performed poorly as a method to determine EBL. Even though the median EBL bias determined by the Triton system was larger than the visual estimation method (13 mL vs. 4 mL), the bias of the visual method had a substantially larger variability, as indicated by the larger IQR (230 mL for visual estimation vs. 74 mL for the Triton measurement). This is also depicted in Figure 4, which shows that despite overall apparent correlation between the visual estimates and reference measurements, there is a wider scatter of data points, compared with Triton measurement which are more consistent and stay closer to the line of perfect correlation.

Lastly, the gravimetric EBL had the highest median bias (389 mL) and largest spread (IQR 287 mL). The correlation between gravimetric EBL and reference method remained statistically significant, but as can be seen in Figure 4, the gravimetric method had a systematic bias in over-estimating the EBL. This is most likely due to the presence of fluid other than blood and debris on the sponges, which are reflected in the increased weight.

Accurate tracking of blood loss during surgical procedures requires an understanding of where the lost blood collects. A major portion of the lost blood collects on surgical sponges but some is also collected by suctioning the surgical field and ends up in canisters (for possible reinfusion using a cell saver system) or discarded. While the Triton system addresses the first part, consideration of the amount of the suctioned blood (alongside with any other fluids that might have diluted it) is also important and this aspect is addressed by a related device (Triton Canister App, Gauss Surgical, Inc., Los Altos, USA) that is also cleared by the FDA. Importantly, the Triton system is not affected by the presence of other fluids on the sponges as its measurements are based on the colorimetric analysis of images focusing on Hb [8].

Although the sample size of this study was justified by a power analysis, the relatively small number of patients spread across a variety of procedures is a potential limitation of this study. Also, blood loss in the cohort was relatively low with only one patient losing greater than 100 g of Hb (by assay method). Further studies among patients with higher blood loss and with varied amounts of surgical irrigation would be helpful.

Table 3 summarizes some of the currently available transfusion guidelines that incorporate surgical blood loss as part of decision making process. Potential lines of study may include new forms of real-time clinical decision support. For example, if expected bleeding curves – expected blood loss over time – for a given procedure or perioperative period can be established, patients who are bleeding excessively may be identified earlier. In addition, knowing the volume of blood contained in laparotomy sponges may improve the efficiency of intraoperative blood recovery. For instance, when a large amount of blood is found to be present in surgical sponges, this blood could be rinsed out and directed into cell salvage devices, then returned to the patient rather than being discarded [18]. The ability to objectively and accurately measure surgical blood loss will undoubtedly lead to better-informed and more timely volume resuscitation and transfusion decisions.

Table 3.

Consideration of rate and blood loss amount as factors in making transfusion decisions

| Guidelines | Patients/Settings | Considerations for RBC Transfusion |

|---|---|---|

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)14 | General surgical patients (perioperative) |

|

| College of American Pathologists (CAP)17 | Unspecified/general patient populations |

|

| Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohematology (SIMTI)16 | General surgical patients (perioperative) |

|

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons and The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (STS/SCA)15 | Cardiac surgery |

|

Acknowledgments

Information for LWW regarding depositing manuscript into PubMed Central: This research was funded by National Institutes of Health grant number T32GM075770.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32GM075770). Equipment for this study was provided by Gauss Surgical, Inc., Los Altos, USA.

Footnotes

This manuscript was screened for plagiarism using Article Checker.

IRB: The investigational protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, CA)

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS AND POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Javidroozi is a consultant for Gauss Surgical, Inc.; Dr. Tully is an employee of Gauss Surgical, Inc.; Dr. Adams is a scientific advisor for Gauss Surgical, Inc.. Authors Konig, Waters, Philip, Ting, Abbi declare that they have no conflict of interest. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for human studies were followed. Patient consent for study of the sponge contents was waived by the IRB.

Contributor Information

Gerhardt Konig, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA. Contribution: This author performed data analysis and manuscript preparation. Attestation: Gerhardt Konig attests to approving the final manuscript and to the integrity of the data analysis reported in this manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: None.

Jonathan H. Waters, Departments of Anesthesiology and Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Contribution: manuscript preparation. Attestation: Jonathan Waters attests to approving the final manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: None.

Mazyar Javidroozi, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center. Contribution: study design, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation. Attestation: Mazyar Javidroozi attests to approving the final manuscript and to the integrity of the statistical analysis reported in this manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: Mazyar Javidroozi is a consultant for Gauss Surgical, Inc.

Bridget Philip, Department of Anesthesiology, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA. Contribution: This author performed data collection and manuscript preparation. Attestation: Bridget Philip attests to approving the final manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: none.

Vicki Ting, Department of Obstetrics, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA. Contribution: This author performed data collection and manuscript preparation. Attestation: Vicki Ting attests to approving the final manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: none.

Gaurav Abbi, Department of Orthopedics, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA. Contribution: This author performed data collection and manuscript preparation. Attestation: Gaurav Abbi attests to approving the final manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: none.

Eric Hsieh, Gauss Surgical, Inc. Contribution: study design, data collection and Figure development. Attestation: Eric Hsieh attests to approving the final manuscript and to the integrity of the statistical analysis reported in this manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: Eric Hsieh is an employee of Gauss Surgical, Inc.

Griffeth Tully, Gauss Surgical, Inc. Contribution: data analysis, manuscript preparation. Attestation: Griffeth Tully attests to approving the final manuscript and to the integrity of the data analysis reported in this manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: Griffeth Tully is an employee of Gauss Surgical, Inc.

Gregg Adams, Department of Surgery, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA. Contribution: This author performed data collection and manuscript preparation. Attestation: Gregg Adams attests to approving the final manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: Gregg Adams is a scientific advisor of Gauss Surgical, Inc.

References

- 1.Shander A, Gross I, Hill S, et al. A new perspective on best transfusion practices. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:193–202. doi: 10.2450/2012.0195-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guinn NR, Broomer BW, White W, et al. Comparison of visually estimated blood loss with direct hemoglobin measurement in multilevel spine surgery. Transfusion. 2013;53:2790–4. doi: 10.1111/trf.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCullough TC, Roth JV, Ginsberg PC, Harkaway RC. Estimated blood loss underestimates calculated blood loss during radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urol Int. 2004;72:13–6. doi: 10.1159/000075266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seruya M, Oh AK, Boyajian MJ, et al. Unreliability of intraoperative estimated blood loss in extended sagittal synostectomies. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:443–9. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.PEDS11180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toledo P, Eosakul ST, Goetz K, et al. Decay in blood loss estimation skills after web-based didactic training. Simul Healthc. 2012;7:18–21. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318230604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griebel L, Prokosch HU, Kopcke F, et al. A scoping review of cloud computing in healthcare. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes AA, Konig G, Ting V, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel system for monitoring surgical hemoglobin loss. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:588–94. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konig G, Holmes AA, Garcia R, et al. In vitro evaluation of a novel system for monitoring surgical hemoglobin loss. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:595–600. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julious SA. Sample sizes for clinical trials with normal data. Stat Med. 2004;23:1921–86. doi: 10.1002/sim.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schorn M. Measurement of blood loss: review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuckerwise LC, Pettker CM, Illuzzi J, et al. Use of a novel visual aid to improve estimation of obstetric blood loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:982–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dildy GA, III, Paine AR, George NC, Velasco C. Estimating blood loss: can teaching significantly improve visual estimation? Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:601–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000137873.07820.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Practice guidelines for perioperative blood transfusion and adjuvant therapies: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:198–208. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Saha SP, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and blood conservation in cardiac surgery: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists clinical practice guideline. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S27–S86. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liumbruno GM, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, et al. Recommendations for the transfusion management of patients in the peri-operative period. II. The intra-operative period. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:189–217. doi: 10.2450/2011.0075-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon TL, Alverson DC, AuBuchon J, et al. Practice parameter for the use of red blood cell transfusions: developed by the Red Blood Cell Administration Practice Guideline Development Task Force of the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:130–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shander A, Javidroozi M. Strategies to reduce the use of blood products: a US perspective. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25:50–8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834dd282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johar, et al. Assessing Gravimetric Estimation of Intraoperative Blood Loss. J Gynecol Surg. 1993;(9):151. doi: 10.1089/gyn.1993.9.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]