Abstract

There has been a great deal of state-level legislative activity focused on immigration and immigrants over the past decade in the United States. Some policies aim to improve access to education, transportation, benefits, and additional services while others constrain such access. From a social determinants of health perspective, social and economic policies are intrinsically health policies, but research on the relationship between state-level immigration-related policies and Latino health remains scarce. This paper summarizes the existing evidence about the range of state-level immigration policies that affect Latino health, indicates conceptually plausible but under-explored relationships between policy domains and Latino health, traces the mechanisms through which immigration policies might shape Latino health, and points to key areas for future research. We examined peer-reviewed publications from 1986–2016 and assessed 838 based on inclusion criteria; 40 were included for final review. These 40 articles identified four pathways through which state-level immigration policies may influence Latino health: through stress related to structural racism; by affecting access to beneficial social institutions, particularly education; by affecting access to healthcare and related services; and through constraining access to material conditions such as food, wages, working conditions, and housing. Our review demonstrates that the field of immigration policy and health is currently dominated by a “one-policy, one-level, one-outcome” approach. We argue that pursuing multi-sectoral, multi-level, and multi-outcome research will strengthen and advance the existing evidence base on immigration policy and Latino health.

Keywords: Latino, structural racism, Immigrant/immigration, race/ethnicity, Health and wellness, law and policy, health inequalities, State-level policy, United States

Introduction

Immigration status in the United States is determined at the federal level, but state-level policies and practices vary substantially across time and place, expanding immigrants’ access to services and benefits in some states while constraining their access in others (Morse et al., 2016). From a social determinants of health perspective, social and economic policies are health policies, but there are gaps in our knowledge about the health effects of policies directed at immigrants (Gee and Ford, 2011; House et al., 2008). This paper therefore reviews and advances research regarding the relationship between the health of Latinos and the state-level immigration-and immigrant-focused policy context, which includes laws and regulatory measures concerning a given topic. This paper summarizes existing evidence about the range of state-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies that affect Latino health, indicates conceptually plausible but under-explored relationships between domains of policy and Latino health, traces the mechanisms through which such policies might shape Latino health, and points to key areas for future research.

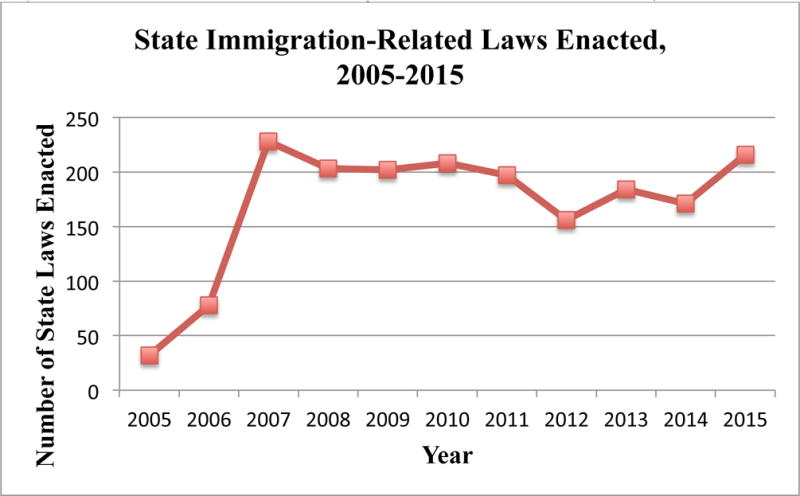

Between 2005 and 2007, substantial popular mobilization for immigration reform in the U.S. failed to bring about legislation at the federal level (Barreto et al., 2009). State-level legislative activity focused on immigration, however, increased precipitously in 2005, and has remained high since 2007 (Morse et al., 2016). Though fluctuations exist, states introduce approximately 1,300 immigration-related bills each year, some intended to increase immigrants’ access to services, benefits and rights, and others intended to restrict them; on average 200 have become law each year (Morse et al., 2016, 2014) (Figure 1). In the past decade, ten states passed a cluster of legislation known as omnibus laws, which impose penalties for the employment or harboring of undocumented immigrants, limit their access to public services, and allow for police stops for the sole purpose of verifying immigration status. This combination of restrictions serves to discourage undocumented immigrants’ very presence in the state (Morse et al., 2012). Legislative activity aimed at undocumented immigrants has also sought to affect (either by expanding or restricting) undocumented immigrants’ access to government-provided health care, identification (driver’s licenses, identification cards), and higher education (with rules or laws regarding admissions, in-state tuition, and financial aid at state universities and colleges) (Gusmano, 2012; Silva, 2015).

Figure 1. Number of State-Level Immigration-Related Laws Enacted, 2005–2015*.

Greater attention to state-level immigration-related policies as a driver of Latino health is justified not just by the proliferation of policies but also by related empirical research. A nascent body of work demonstrates how state-level policies unrelated to healthcare access affect health outcomes among members of marginalized groups (Krieger et al., 2013). Our approach is well-developed by Hatzenbuehler and colleagues who have demonstrated that the policy climate—a composite of the existing laws, their enforcement and practice, and the debates surrounding these laws—affects a wide range of health outcomes for sexual minorities (for a review see Hatzenbuehler, 2016).

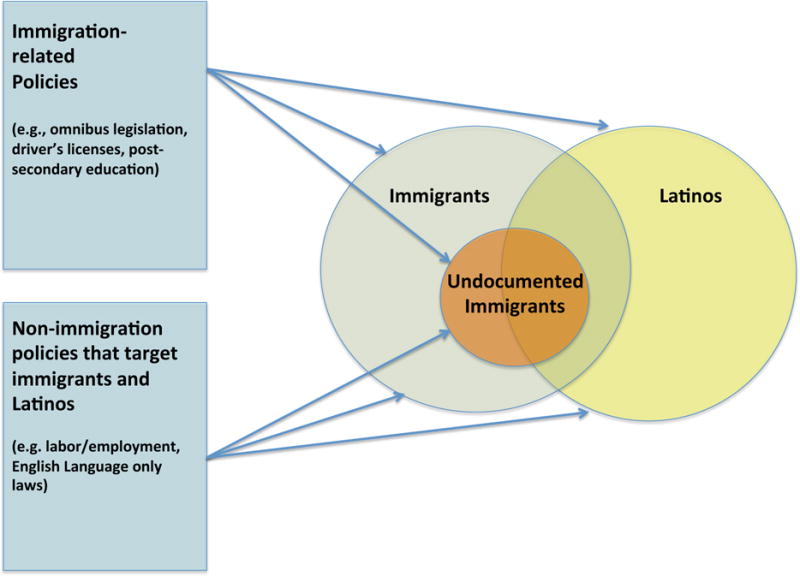

Our focus here is on state-level immigration- and immigrant-focused policies as social determinants of health for all Latinos, irrespective of migration status, despite the obvious fact that not all Latinos are immigrants, much less undocumented immigrants (Figure 2). First and most importantly, evidence suggests that exclusionary policies’ harmful effects can extend beyond their stated target to affect authorized immigrants and U.S. citizens (Moya and Shedlin, 2008; Sabo and Lee, 2015). Restrictive state-level immigration policies have harmful effects on immigrant and non-immigrant Latinos, particularly since approximately nine million Americans live in mixed-status families and nearly 10% of babies born each year have one undocumented parent (Aranda and Vaquera, 2015; Taylor et al., 2011). Moreover, for Latinos and Hispanics (the latter being a term we only use in reference to research that employs Hispanic as a category), race and immigration status are often conflated, and in the popular imagination Latino immigrants are frequently perceived to be undocumented (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). This means that anti-immigrant sentiments can facilitate racism and xenophobic attitudes toward all Latinos, irrespective of immigration status. Based on this rationale, the paper examines what is known about the impacts of state-level immigration and immigrant-oriented legislation on the health of all Latinos. We acknowledge, however, that when evidence demonstrates that particular policies negatively impact Latino health, there is likely an even stronger impact on the health of immigrant or undocumented Latinos (Rhodes et al., 2015; Sabo and Lee, 2015).

Figure 2. Relationship between state-level policies and the health of immigrants, Latinos, and undocumented immigrants.

A representation of the relationship between state-level policies and immigrants, undocumented immigrants, and Latinos. Although these groups must not be conflated, they can overlap. Additionally, health impacts in one group may influence others that do not belong to that group, but share a relationship with individuals in that group, such as kinship. Not drawn to scale.

The health status of Latinos in the US

Latinos are the largest immigrant group in America. In 2012, 42.7% of the U.S. foreign-born population came from Mexico, Central America, or South America (Brown and Patten, 2014); 35.5% of Latinos in the U.S. are foreign-born (Krogstad and Lopez, 2014). Latinos are less likely to have access to healthcare compared to non-Latino whites (Moya and Shedlin, 2008). This is especially true for undocumented Latino immigrants and their children, who are often ineligible for public insurance programs and, even when eligible, may be fearful of interacting with the healthcare system (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2010). Nearly 27% of Hispanics under age 65 were uninsured in 2014, a proportion that is twice that of non-Hispanic whites (CDC, 2014); nearly two-thirds of undocumented Latino immigrants lack health insurance (Bustamante et al., 2012).

Latinos also experience higher rates of morbidity and mortality for specific chronic conditions compared to non-Latinos. Hispanic adults are at disproportionate risk of diabetes (versus non-Hispanic white and Asian adults), HIV/AIDS (versus non-Hispanic white adults) and other conditions (CDC, 2016; Peek et al., 2007). Latinos with diabetes are more likely to experience related morbidities and mortality than non-Latinos (Peek et al., 2007). Among Latino immigrants, the process of migration itself can impact mental health; for example, Mexican migrants ages 18-35 have an elevated risk of depression and anxiety disorders compared to their counterparts who remained in Mexico (Torres and Wallace, 2013).

Current study

This review fills a critical gap in the literature on structural racism and health by exploring how state-level immigration policies may impact Latino health, and by emphasizing the importance of states as units of analysis. In addition, we look beyond immigration-specific policies to other policies that might disproportionately affect immigrants and Latinos, such as labor practices and language restrictions (e.g., English-only laws). This methodological approach has been applied previously (Galeucia and Hirsch, 2016) to examine how the policy context can impact Latino migrants’ HIV-related vulnerability. Thus, we examine how the policy environment in the state as a whole may affect multiple health-related outcomes, including those for which Latino health disparities are most extreme.

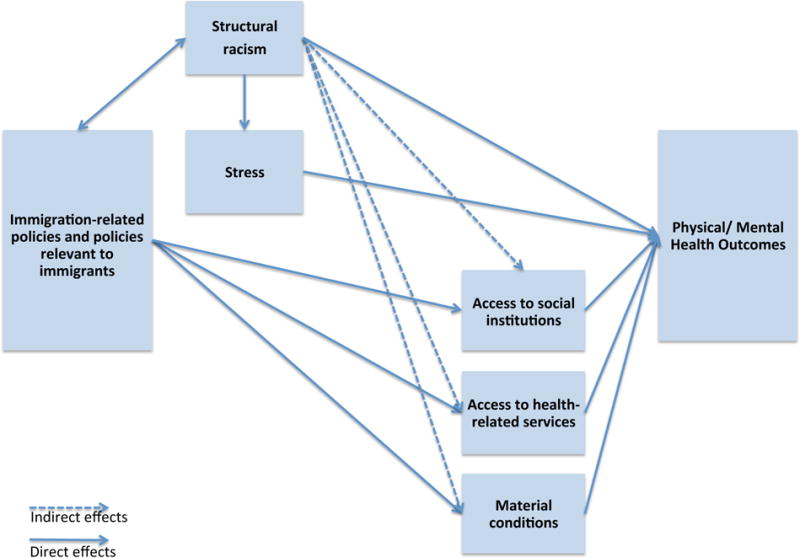

We begin with a description of the theoretical framework that organizes this paper and the methods. Next, we outline what is known about the health impacts of such policies, organizing the discussion by relevant policy domain, and propose four pathways (Figure 3) through which state-level immigration policies could contribute to Latino health disparities: 1) stress produced by structural racism; 2) access to beneficial social institutions, such as education; 3) access to health-related services; and 4) the material consequences of inequality, including limited access to food, income, and adequate housing. We conclude with a discussion and recommendations for further research.

Figure 3.

Theorized pathways through which immigration-related policies and policies relevant to immigrants may influence Latino health

Theoretical framework

Our work is informed by three conceptual approaches, each of which points to policy’s impact on population health. First, the social ecological model, which identifies how factors at multiple levels influence health (Sallis et al., 2008), provides a theoretical framework for considering how upstream factors, such as state-level policy, shape individual and community wellbeing. Second, we draw on prior work that argued for greater attention to ‘meso-level’ factors — that is, factors between the micro-individual level and macro-structural level that have an empirically described or conceptually plausible relationship to a health-relevant practice and that are potentially modifiable through collective action (Hirsch, 2014). The meso-level is relevant because it calls attention to policy as a modifiable dimension of the social ecological context.

Structural racism provides a third framework for understanding the role of broad structures, including laws and policies, in producing health inequalities (Williams and Collins, 1995). Structural racism refers to the “social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial and ethnic groups”; research depicts exclusionary immigration policies as a form of structural racism (Gee and Ford, 2011, p. 116; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). This rendering of immigrants as racialized ‘others’ can create inequalities that influence health through multiple pathways (Gee and Ford, 2011; Powell, 2008). Gee and Ford (2011) also argue that immigration-related policies can be a form of structural racism that may limit healthcare access and contribute to stress, discrimination and illness among racial/ethnic minorities. Theories of structural racism point to two ways in which policies can negatively affect racial/ethnic minorities. One is through directly promulgating racism by restricting certain rights or protections (e.g., Arizona’s SB 1070 law, which allowed officers to stop individuals with the sole purpose of verifying immigration status). Another is through inaction—that is, policy inattention towards the concerns of marginalized groups (Link and Hatzenbuehler, 2016). Such inaction can be the result of motivations (e.g., those in power directly benefit from the racism) or of powerful groups attending to their own concerns, and ignoring the needs of the racial/ethnic minorities (Aranda and Vaquera, 2015; Gee and Ford, 2011; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). These three conceptual approaches point to state-level policies as potential drivers of Latino health outcomes.

Methods

The goal of this literature review was to examine empirical evidence in order to identify policy domains relevant to Latino health and the pathways through which state-level immigration policies may impact Latino health; it was not to conduct a systematic review of research on the relationship between immigration policy and Latino health, nor to assess the methodological strength of existing evidence. This literature review enabled us to determine whether there was evidence for certain pathways and to identify gaps in the evidence base. Based on this goal of identifying relevant policy domains and pathways, we applied a modified version of the PRISMA statement to conduct the review (Moher et al., 2009). This approach provided ample illustrative evidence to identify and inform the four pathways outlined in this paper.

Our literature review followed a two-step process. First, we identified relevant policy domains that could affect Latino health. We did so based on peer-reviewed sources (e.g., policy analyses), prior research (e.g., (Androff et al., 2011; Galeucia and Hirsch, 2016; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017; Hirsch, 2003a, 2003b; Toomey et al., 2013) and grey literature. Overall, as shown in Figure 2, we considered four types of state-level policies: those specifically aimed at immigration across multiple domains (the so-called omnibus policies); immigration-related policies that specifically target immigrants’ access to health, education, drivers’ licenses, and other state functions; non-immigration policies that target immigrants (e.g., English-language only laws) and policies that do not directly target immigrants but that have a disproportionate impact on Latinos—such as those affecting agricultural workers. Substantively, these four categories include the following policy domains: immigration and enforcement-related omnibus laws, labor/employment regulations, education, healthcare, driver’s licenses, and social services (Table 1). Grey literature—such as reports from the National Conference of State Legislatures and the National Immigration Law Center—served as a point of comparison to think about areas of policy-making that might be relevant for Latino health and yet under-explored in the peer-reviewed literature; it also ensured we captured the full policy landscape. Additionally, this approach allowed us to explore how policy makers and those conducting policy research frame and address immigration- and health-related questions. After creating an initial list of policy domains, we sought feedback from legal scholars whose work focuses on immigrant wellbeing to verify that our list of policy domains included all relevant categories.

Table 1.

Examples of immigration- and immigrant-related policy domains and the plausible pathways through which they may impact Latino health

| Policy Type | Plausible Pathways | Examples of evidence Linking policy domains to Health |

|---|---|---|

| Immigration & Enforcement-related Omnibus laws |

|

Berk and Schur 2001; Hardy et al 2012; Rhodes et al 2015; Salas, Ayon, and Gurrola 2013; Sabo et al 2013; Sabo and Lee 2015; Santos, Menjivar, and Godfrey 2013; Toomey et al 2013; White et al 2014 |

Labor/employment including:

|

|

Arbona et al 2010; Fleming et al 2016 |

Post-secondary education: Access for undocumented students to

|

|

Salas, Ayon, and Gurrola 2013; Kaushal 2008 |

Primary and secondary education

|

|

|

Education & employment

|

|

|

| Driver’s Licenses and Identification |

|

Rhodes et al 2015; Evenson et al 2002 |

Health

|

|

Graefe 2015; Kaushal and Kaestner 2005 |

Other services: access for immigrants to

|

|

Then, we searched for empirical research on the relationship between state-level policies across all of the above-mentioned domains and Latino health. Articles on the health-related impacts of relevant policies were identified by searching Social Science Citation Index, Pegasus-Columbia Law Library’s online catalog, PubMed, Web of Science, and Psychinfo for the following key words in various combinations: immigrant/immigration, undocumented, Latino/Hispanic, state, law, United States, policy/policies, health and wellness. These databases provided articles from a wide range of disciplines (e.g., anthropology, political science, psychology, law, sociology and public health), providing a comprehensive list of current research on the potential health impacts of immigration-related policies.

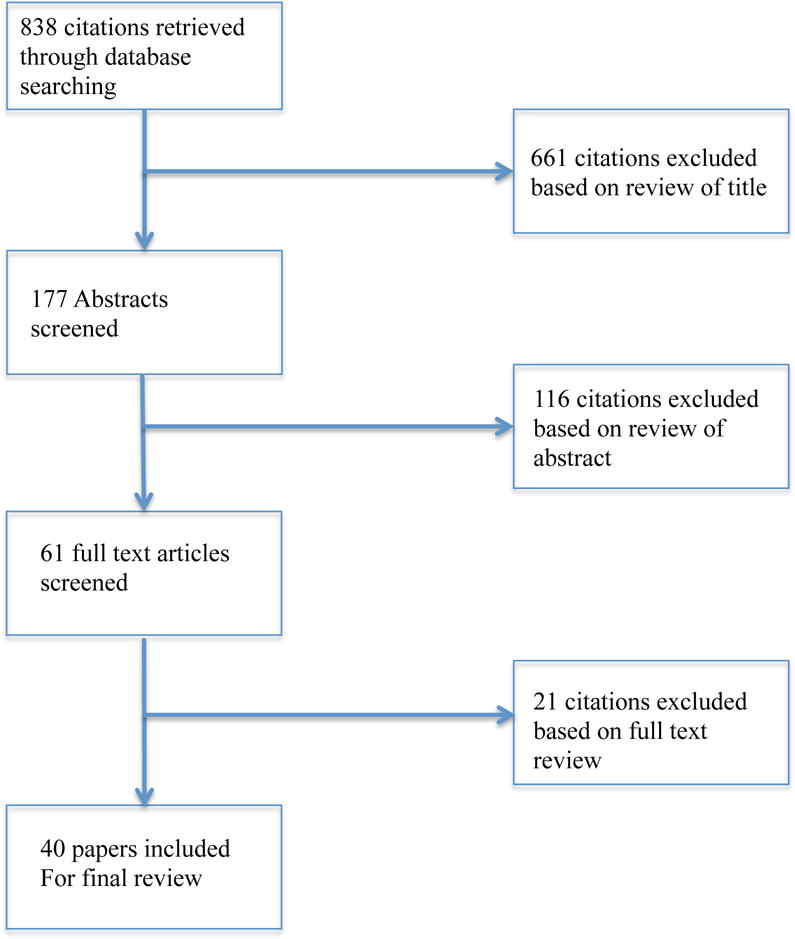

We searched for peer-reviewed articles from 1986–2016 due to the proliferation of statelevel legislation after the 1986 passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) which, among other things, required employers to attest to employees’ immigration status and made it illegal to knowingly hire undocumented immigrants. This search produced a total of 838 citations (See Figure 4 for flow chart of review process). The authors first reviewed the titles, then abstracts and ultimately complete manuscripts and included articles if they were written in English and focused on state-level immigration or immigrant-related policies, Latinos, and had a health disparity-related outcome; articles were excluded if they did not include both immigration-related policies and describe an empirical study. A total of 40 articles met these criteria [ONLINE FILE A] and informed the four pathways identified in this article.

Figure 4.

Flow diagram of search methods and manuscript selection

Results

Health impacts by policy type

In Figure 3, we present four pathways that emerged from our literature review through which state-level immigration- and immigrant-focused policies may influence Latino health. First, state action has symbolic significance, communicating whether or not immigrants are welcome regardless of immigration status. As noted above, immigration-related policies may also ‘spill over’ and affect non-immigrant Latinos. We see this as a form of structural racism which, as Gee and Ford (2011) have argued, contributes to ill-health in part through stress. Second, policies can impact health by limiting access to health-promoting social institutions such as secondary and higher education; Latinos already experience 11% lower high school graduation rates than white students across the U.S. and are underrepresented in higher education (Kena et al., 2016). Third, policies regulate both undocumented and documented immigrants’ access to health-related services and care. Finally, policies can affect the material conditions of people’s lives by influencing access to state benefit programs and to the labor market, as well as influencing workplace safety and working conditions, thus affecting income, food security and housing.

This section summarizes evidence for the health impacts, whether positive or negative, of each policy domain identified during the review (Table 1). It then discusses the pathways through which they might impact Latino health. For each policy domain, we describe example policies and discuss them in relation to the pathways described in Figure 3.

Immigration- and enforcement-related policies

Immigration-focused omnibus laws explicitly or implicitly derive their motivation from the desire to drive undocumented—and sometimes even documented—immigrants away from the state and restrict their rights and access to services. For example, a sponsor of Alabama’s 2011 omnibus law commented on his hope that the law would “make their lives difficult and they will deport themselves” (Fausset, 2014). The text of Arizona’s omnibus legislation, SB 1070, states, “The intent of this act is to make attrition through enforcement the public policy of all state and local government agencies in Arizona” (Senate Bill 1070, 2010). State policies that encourage immigration enforcement by local and state police officers may influence the health of Latinos through all four pathways in Figure 3.

The structural racism and resulting stress generated by such legislation discourages Latino immigrants, both documented and undocumented, from engaging in many aspects of daily life (Sabo et al., 2014). As suggested in Figure 3, via a pathway of structural racism, this legislation could plausibly reduce access to healthcare and detrimentally affect the material conditions of people’s lives (Hardy et al., 2012). Evidence suggests that stress and stigma generated by the passage of immigration-related legislation increased food insecurity for mixed-status families (Potochnick et al., 2016) and lowered enrollment in the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) (Winham and Armstrong, 2015). Arizona’s passage of SB 1070 negatively impacted Latino youth’s sense of being American, which caused a lower level of psychological well-being and lowered self-esteem (Santos et al., 2013). If exclusionary policy climates contribute to elevated stress, the pathway on structural racism suggests that this could likely increase levels of high blood sugar, high blood pressure, and other health risks among Latinos and Latino immigrants (Hardy et al., 2012).

Secondly, immigration-focused legislation impacted Latinos’ access to social institutions and often created confusion over eligibility for services, even for legal immigrants; even when states do provide benefits to immigrants they are primarily limited to legal permanent residents or refugees (Berk and Schur, 2001; Hagan et al., 2003). Exclusionary legislation can also drive immigrants to relocate to other states or to rural areas, which may lack the infrastructure to provide culturally- and linguistically-appropriate support for access to services such as food, education, or housing (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012).

As suggested by the healthcare access pathway, state-level immigration policies can reduce Latinos’ access to healthcare, with ample evidence of a spillover effect on all Latinos for policies intended to reduce access for immigrants. Proposition 187 in California was the most extreme state-level immigration-related legislation to date at its passage in 1996. Research showed that diagnoses of autism and tuberculosis decreased among Latinos following its implementation and rose again after its repeal, underlining the serious health consequences when such legislation restricts healthcare access (Berk and Schur, 2001; Fountain and Bearman, 2011; Ziv and Lo, 1995). A study of healthcare and public assistance utilization conducted before and after the passage of Arizona’s SB 1070 revealed decreased health service use among Mexican-American mothers, the majority of whom were US citizens, and their US-born infants (Toomey et al., 2013). After police in North Carolina signed 287(g) agreements with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, taking on the responsibility of enforcing federal immigration laws, Latina mothers sought prenatal care later and received lower-quality care than non-Latina mothers (Rhodes et al., 2015). Job insecurity as a result of exclusionary policies also decreased the affordability of care, and mistreatment and discrimination by clinic staff reduced the accommodation and acceptability of care (White et al., 2014). White and colleagues (2014) also found that Alabama’s omnibus immigration bill, HB 56, caused many immigrants, regardless of their status, to falsely believe that they were ineligible for healthcare and for clinic staff to erroneously reject some eligible patients who sought care.

Lastly, the pathway on material access suggests how exclusionary immigration policies can impact wages and working conditions for both undocumented and documented Latinos. The fear of being stopped and apprehended (Hardy et al., 2012) can affect Latinos’ ability to access resources ranging from nutrition and physical activity to employment. For example, access to transportation, including the ability to drive, is a barrier to physical activity among Latina immigrants (Evenson et al., 2002).

Employment/labor-related policies

Policy domains that govern the labor market and working conditions may impact Latino health through their effect on structural racism and material resources. Many states have recently adopted requirements that employers participate in the federal E-Verify system, which compares employees’ tax forms to federal government data to ensure that employers avoid hiring undocumented workers. E-Verify laws intentionally reduce undocumented workers’ access to the labor market, but they may also lead to a more general feeling of exclusion, and to negative mental health outcomes among legal immigrants and non-immigrant Latinos (Arbona et al., 2010), affecting health through the structural racism-related pathway.

The material pathway demonstrates how employment-related policies can influence the health of Latinos in both positive and negative ways by affecting wages and working conditions, particularly agricultural-related policies. Agricultural workers are predominantly Latino (83% in 2012), and nearly half are undocumented (US Department of Labor, 2012). Even those who are documented may exist in a state of substantial vulnerability, as temporary H2A agricultural worker visas are issued for workers on a particular farm, thus requiring them to endure labor conditions on that farm or else risk losing their visa. States may elect to include agricultural workers in benefits beyond the extent of federal policies—for instance, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Washington require agricultural workers be paid minimum wage and be entitled to workers’ compensation—with potential benefits related to earnings and consequently for the health of the Latino immigrant workers.

Because immigrant Latinos account for a disproportionate share of agricultural jobs, they are heavily affected by agricultural employers’ exemption from providing workers’ compensation in many states (McEowen, 2015). This puts agricultural workers at disproportionate risk of being unable to secure care if they experience a work-related accident. We found no empirical research examining the impact of state E-Verify, minimum wage, overtime, and worker’s compensation provisions on immigrant or Latino health; however, research among Latino immigrants in North Carolina found that the discrimination and marginalization resulting from dangerous working conditions and unsteady employment affected men’s health and wellbeing (Fleming et al., 2016). In addition, poverty-focused research clearly demonstrates that income and material resources have a critical impact on health (Alaimo et al., 2001; Ettner, 1996) and other work has shown that workers’ compensation positively affects self-reported health among injured workers (Lippel, 2007).

Education-related policies

State-level policies that dictate education access for undocumented students and English language learners may influence Latino health through the pathways of structural racism and access to social institutions and material goods. Relevant elementary and secondary education policies include bans on bilingual education or, as in Arizona, a ban on ethnic studies (Fischer, 2017). Policymakers designed this legislation to prohibit curricula that celebrated the history and culture of minority groups, and specifically a Mexican-American studies class that was later shown to increase graduation rates and standardized test scores (Cabrera et al., 2014). This type of legislation might heighten feelings of exclusion by using a school’s “hidden curriculum” to communicate that Latino culture and history are not valued by the educational system or government (Fields, 2008), thus negatively influencing health through the structural racism-related pathway.

Education access is one of the strongest predictors of health (Ross and Wu, 1995). Limiting post-secondary education access influences undocumented immigrants through the social institutions and material resources pathways. Even at a young age, undocumented Latinos fear that they will be unable to achieve their educational dreams of attending college due to legal restrictions (Salas et al., 2013). Furthermore, bans on education- and employment-based affirmative action in several states may have detrimental consequences for the social and economic mobility of immigrants and Latinos, with possible adverse health consequences. Together, policies limiting education and employment hinder access to the opportunities and resources that lead to positive health outcomes over the life course.

Research suggests that post-secondary education policies could also improve health outcomes by including access at public colleges and universities to admissions, in-state tuition, and financial aid for undocumented immigrants, many of whom were brought to the country as young children (Kaushal, 2008). These policies include state-level Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Acts designed to emulate the eponymous federal legislation package which would allow undocumented immigrants in the U.S. to obtain conditional residency if they entered the U.S. before age 16, completed high school, and passed criminal background checks; to obtain permanent residency one must attend post-secondary education or serve in the U.S. military. Increased college education availability and affordability could lead to a sense of inclusion and hope as well as to greater earning capacity, and thus improved resources and health (Flores, 2010; Kaushal, 2008). Kaushal (2008) found that providing in-state tuition to undocumented students was associated with increased college enrollment and the proportion of students with at least an associate degree. Another study showed that foreign-born noncitizens enrolled in college at increased rates in states that offer instate tuition to undocumented students compared to states that do not, suggesting a potential positive impact on health (Flores, 2010). In contrast, other states restrict access to education-related benefits, such as the six states that exclude undocumented people from eligibility for instate tuition, two of which entirely bar admission for undocumented individuals.

Driver’s license-related policies

Driver’s licenses affect physical and social mobility, employment, and mental health (e.g., resulting from fear of driving without a license). Additionally, the lack of a driver’s license deters Latino immigrants—regardless of documentation status, and particularly those living in mixed-status families—from seeking health care; Latino immigrants report being afraid to drive for fear of arrest and only do so for the most imperative reasons (e.g., to attend work) (Rhodes et al., 2015). Driver’s license policies may therefore influence Latino health—both positively and negatively—through all four proposed pathways: via structural racism; access to social institutions (such as school and social programs); healthcare services; and material resources (e.g., access to employment and healthy foods). Twelve states currently accept driver’s license applications regardless of immigration status. Other states offer driving privilege cards that are not valid for identification and contain a visual marker to denote an individual’s immigration status (e.g., “no lawful status”); a few states have enacted policies that explicitly prohibit issuing driver’s licenses to undocumented people (Teigen and Morse, 2013). Access to driver’s licenses represents a critical and rapidly-changing area of immigration-related policy, particularly given the importance of mobility for access to healthcare services and employment, and the proportion of the nation’s undocumented immigrant population that lives in areas without adequate public transportation.

Healthcare-related policies

Healthcare-related policies include access to healthcare coverage for documented and undocumented immigrants, requirements that healthcare providers participate in trainings in culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS), and policies that require healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants. The U.S. has a five-year waiting period before legal immigrants are eligible for federal benefits. This means that even legal immigrants may be unable to find affordable medical care without state-specific policies to facilitate access, thus demonstrating the importance of the healthcare access pathway. California, New York, and Washington, for example, have eliminated the five-year waiting period making legal immigrants immediately eligible for Medicaid if they meet other criteria (Gusmano, 2012). Other states provide additional funding to federally qualified health centers, which are required to serve patients regardless of immigration status (Gusmano, 2012). Even with these benefits, Latinos are overrepresented among the uninsured (Adams et al., 2013), which can result in delayed diagnoses, lack of treatment, and other precursors to negative health outcomes. Numerous studies have examined the relationship between healthcare-related policies and healthcare access among immigrants, particularly at the federal level. However, there is little peer-reviewed research on the relationship between state-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies and health outcomes, with most work to date focused on access to care.

Only one state, Arizona, requires that state health and social service employees report suspected undocumented immigrants to authorities. The pathways on structural racism and healthcare access suggest how such policies could powerfully impact immigrants and their family members, regardless of legal status, by generating fear around applying for state services, and thereby discouraging their use. Conversely, cultural competency training for healthcare providers improves providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills as well as patient satisfaction, although no change in health outcomes has yet been demonstrated (Beach et al., 2005). It is possible that culturally and linguistically appropriate services could influence Latino health through the structural racism pathway by promoting inclusivity, and through the healthcare access pathway by offering better care and increasing uptake among Latinos.

Policies related to other services

Eligibility for federally-funded food and cash assistance is limited by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, leaving states to determine which, if any, immigrants are eligible for such services. As of 2010, seven states provided supplemental programs for food assistance for at least some qualified immigrants and 22 states provided cash assistance to qualified immigrants, though eligibility varies across states by type of immigrant group (Fortuny and Chaudry, 2011). These sources of support could directly improve nutrition and other basic needs through the material pathway, though we could not find any research on the health impacts of this policy.

Discussion

This paper synthesizes the evidence regarding state-level immigration and immigrant-related policy as a driver of Latino health outcomes in the U.S. and provides a conceptual model for how to think about the pathways that link these policies to health. The paper highlights the importance of examining a variety of policy domains including: omnibus policies that target multiple immigration-related domains; immigration-specific policies (e.g., around education access and driver’s licenses), non-immigration related policies that target immigrants (e.g., English-only laws), and policies likely to disproportionately impact Latinos (e.g., agricultural labor policies). Specifically, this paper identified four pathways through which state-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies can impact Latino health: through structural racism and access to social institutions, medical care, and material goods.

Recommendations for further research

There are important gaps in knowledge about the relationship between immigration-related and immigrant-focused policies and Latino health. In this section, we highlight several key areas to guide future research.

First, although most research fit the four pathways we describe, some evidence contradicts the notion that policies targeted at immigrants, whether documented or undocumented, might affect Latino health more generally. One study found a 10% increase in food insecurity among non-citizen Mexican households after the passage of immigration-related legislation (which fits within our framework), but found no ‘spillover effect’ to the broader Latino community (Potochnick et al., 2016). This may suggest that spillover effects are limited to specific pathways (e.g., healthcare seeking) or that there are other circumstances under which they do not exist. These hypotheses require empirical testing. Additionally, some studies that fit within the framework also suggested additional pathways that are intriguing but for which we found no other empirical support. These pathways include the impact of decreased trust of public officials (Salas et al., 2013), legal cynicism (Kirk et al., 2012), and the impact of moving to more rural/non-traditional immigrant communities (Hardy et al., 2012). Each of these pathways require greater attention in future research. Thus, future research should draw on, but also refine and potentially complicate, our model of the pathways through which the state-level policy environment influences Latino health.

Second, we have discussed how specific policy domains either affect Latino health or could, through our four proposed mechanisms, plausibly do so. It is also important, however, to consider the policy climate in the aggregate, including both restrictive and inclusionary policies. One model of this approach comes from sociology and economics and examines how welfare-related policies within and across states —both individually and in the aggregate—impact health outcomes (Bergqvist et al., 2013; Fosse et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2006). We are aware of only one study that examined how the state-level immigration-related policy climate as a whole impacts Latino health. Researchers created a multi-sectoral policy climate index that included 14 immigration and ethnicity-specific policies and then linked this index to individual-level mental health outcomes among Latinos (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017). Latinos in states with a more exclusionary policy climate had 1.14 times the rate of poor mental health days compared to Latinos in less exclusionary states (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017). This work suggests that a broad set of laws across multiple sectors including transportation, education, labor, health and social services are consequential for Latinos’ mental health.

Third, more disaggregated data are required to systematically examine whether the relationship between policy context and Latino health outcomes operates similarly or differently among specific subgroups of Latinos. In particular, advocates and researchers have called for work that separates Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and other Latino subgroups with distinct histories of settlement and assimilation. Disaggregating results by Latino subgroups will allow researchers to determine whether certain groups are disproportionately affected by state-level immigration laws. Similarly, few population-level data sets collect country of origin or documentation status; this may protect participants and reduce research mistrust, but it also limits our capacity to assess how policy affects the health of Latino subgroups. Assessing documentation status is particularly important because undocumented immigrants are more likely to report discrimination in healthcare settings and are less likely to have insurance than documented immigrants or American citizens, making them particularly vulnerable (Goldman et al., 2005).

Fourth, the majority of research on immigration policies and Latino health has focused on the state level, though other research also acknowledges the importance of expanding research to include municipal-level policies (Donato and Rodriguez, 2014; Sabo et al., 2014; Toomey et al., 2013) and federal level (Hardy et al., 2012; Kaushal and Kaestner, 2005). Future work should not only move beyond state-level policies, but also examine how immigration-related polices at multiple levels simultaneously impact Latino health. For example, places like Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Denver are considered ‘sanctuary cities’ because they do not allow law enforcement to inquire about an individual’s immigration status (Donato and Rodriguez, 2014), and some municipalities (e.g., New York City and San Francisco) will provide government-issued identification cards to undocumented immigrants which allow them to open bank accounts and access some city services. Future work should therefore examine whether more proximal levels of policy—such as at the city level—exert stronger health effects than policies at a more distal level—such as the state (e.g., how might living in a ‘sanctuary city’ in an exclusionary state impact the health of undocumented immigrants?).

Fifth, in order to encompass the full breadth of the policy environment as experienced by the residents of that region, research needs to expand beyond statutes passed by state legislatures, which has been the focus of most work to date. We therefore argue for the need to include policies resulting from administrative, executive, and judicial decisions. Administrative decisions are those that govern the procedures of an organization (e.g., a university system), executive decisions are those made by executives (e.g., governors), and judicial decisions are those made by the courts (e.g., same-sex marriage laws). Affirmative action, a policy that may impact Latino health and wellbeing, provides an example of the myriad ways a policy can be enacted: New Hampshire’s affirmative action ban occurred legislatively, Georgia’s occurred through a judicial decision, and California’s via voter proposition (Morse et al., 2016). In 2012, President Obama issued an executive action called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) that allows certain undocumented immigrants who entered the country as minors to receive, among other things, a driver’s license (Morse et al., 2016). In response, governors in Nebraska and Arizona issued counter-executive orders prohibiting the issue of driver’s licenses for DACA recipients.

Sixth, laws and policies reflect cultural values. At the same time, however, recent research also suggests that laws and polices shape social/cultural norms, including attitudes toward stigmatized groups (Kreitzer et al., 2014). We therefore need to understand how both policies and attitudes affect the health of Latinos. One methodological challenge to doing so is that few existing instruments that measure racism incorporate anti-immigrant sentiment, which likely under-estimates the experiences of immigrant communities (Gee et al., 2009).

Seventh, understanding the relationship between policies and Latino health is of course not only relevant in the U.S. Policies regarding immigrant incorporation vary widely across the European Union and are also likely to influence immigrant health. Similarly, state-level policies likely influence the health of both documented and undocumented immigrants that are not Latino, though further research is needed. Eighth, the majority of existing work examines how policies can be detrimental to Latino health. Future work should examine how policies (e.g., related to accessing higher education or driver’s licenses) might improve Latino health and mitigate health disparities.

Ninth, attention to specific outcomes and precursors is needed. Most research to date has focused on immigration policy and Latino’s healthcare access. However, there may be variability in how the policy context shapes other health outcomes, such as diabetes-related mortality, how it affects key precursors of chronic disease, such as obesity, or how it shapes infectious diseases transmission. Existing population-level data sets that could help address such questions include the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Limitations

Although our review methodology attempted to conduct a broad and thorough initial search, limitations remain. We included grey literature to help identify relevant policy domains, but there are likely organizational websites or reports that did not appear in our searches. Though our search identified over 800 articles, some studies may have been missed due to variations in key words. Also, since our focus was on Latinos in the U.S., we only searched literature published in English. Finally, this paper included only state-level policies. Immigration-related policies across multiple levels (e.g., at the municipal, state, and federal level) likely impact Latino health, and it is important to examine how these policies interact to drive health disparities. Also, as we note, the four pathways we present reflect our critical synthesis of existing evidence; that model is a heuristic for thinking about how policy gets under the skin and impact health, not a comprehensive depiction of every possible pathway that researchers could discover.

Conclusion

Research on the impact of state-level policies on Latino health is important because it explores the effect of a modifiable structural variable—policy—on a vulnerable population. Perhaps the most urgent question at the present moment is the extent to which a supportive state-or municipal-level policy context can buffer the intense xenophobia that characterizes the current US federal policy landscape (Hirschfeld-Davis, 2017). This line of research could identify how structural racism and state-level policies impact the health of Latino populations, ultimately promoting the development of more inclusive and health-promoting policies. Such research might also promote collaboration among advocates in the areas of immigration, education, child and family welfare, labor, racial justice, social justice, and public health by articulating the shared interests that are at stake. The wealth of evidence suggests that exclusionary policies negatively affect the health of Latinos in the U.S.—regardless of immigration- or documentation-status. We have suggested additional avenues for future inquiry that we hope will generate new work on the role of policies in shaping the health of Latino populations.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies influence Latino health

Policies aimed at undocumented immigrants ‘spill over’ and affect all Latinos

State-level immigration policies shape Latino health through four pathways

Pathways include racism and access to institutions, healthcare, and material goods

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a pilot grant from the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (P30-MH43520; PI: Robert Remien, Ph.D.). During initial data collection, Dr. Philbin was supported by an NIMH training grant (T32-MH19139 Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; PI: Theodorus G.M. Sandfort, Ph.D.) Dr. Philbin currently receives support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA039804A). Dr. Hirsch was partially supported by the Columbia Population Research Center (P2-CHD058486).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams P, Kirzinger W, Martinez M. Summary Health Statistics for the US Population. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2013. (National Health Interview Survey, 2012. (No. 10(259)), Vital Health Statistics). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA, Jr, Briefel RR. Food insufficiency, family income, and health in US preschool and school-aged children. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:781. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Androff DK, Ayón C, Becerra D, Gurrola M, Salas L, Krysik J, Gerdes K, Segal E. U.S. Immigration Policy and Immigrant Children’s Well-being: The Impact of Policy Shifts. J Sociol Soc Welf. 2011;38:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda E, Vaquera E. Racism, the Immigration Enforcement Regime, and the Implications for Racial Inequality in the Lives of Undocumented Young Adults. Sociol Race Ethn. 2015;1:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, Wiesner M. Acculturative Stress Among Documented and Undocumented Latino Immigrants in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32:362–84. doi: 10.1177/0739986310373210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto MA, Manzano S, Ramirez R, Rim K. Mobilization, Participation, and Solidaridad Latino Participation in the 2006 Immigration Protest Rallies. Urban Aff Rev. 2009;44:736–764. [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes MW, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Cultural Competency: A Systematic Review of Health Care Provider Educational Interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergqvist K, Yngwe M, Lundberg O. Understanding the role of welfare state characteristics for health and inequalities — an analytical review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. J Immigr Health. 2001;3:151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Patten E. Statistical Portrait of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States, 2012. 2014. (Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project). [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, Carter-Pokras O, Wallace S, Rizzo J, Ortega A. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: the role of documentation status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:146–155. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NL, Milem JF, Jaquette O, Marx RW. Missing the (Student Achievement) Forest for All the (Political) Trees Empiricism and the Mexican American Studies Controversy in Tucson. Am Educ Res J. 2014;51:1084–1118. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. HIV Among Hispanics/Latinos [WWW Document] Cent Dis Control Prev. 2016 URL http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispaniclatinos/

- CDC. Summary Health Statistics. 2014. (National Health Interview Survey). [Google Scholar]

- Donato K, Rodriguez L. Police Arrests in a Time of Uncertainty The Impact of 287(g) on Arrests in a New Immigrant Gateway. Am Behav Sci. 2014;58:1696–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL. New evidence on the relationship between income and health. J Health Econ. 1996;15:67–85. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(95)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, Sarmiento OL, Macon ML, Tawney KW, Ammerman AS. Environmental, Policy, and Cultural Factors Related to Physical Activity Among Latina Immigrants. Women Health. 2002;36:43–56. doi: 10.1300/J013v36n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausset R. In Alabama Town, Obama Immigration Move Brings Hope and Sneers. N Y Times. 2014;12 [Google Scholar]

- Fields J. Risky lessons: Sex education and social inequality. Rutgers University Press; Piscataway, New Jersey: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H. Lawmaker seeks to expand limits on ethnic-studies at Arizona schools. Ariz Dly Star 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P, Villa-Torres L, Taboada A, Richards C, Barrington C. Marginalisation, discrimination and the health of Latino immigrant day labourers in a central North Carolina community. Health Soc Care. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hsc.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores SM. State Dream Acts: The Effect of In-State Resident Tuition Policies and Undocumented Latino Students. Rev High Educ. 2010;33:239–283. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny K, Chaudry A. A Comprehensive Review of Immigrant Access to Health and Human Services. The Urban Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fosse E, Bull T, Burstrom B, Fritzell S. Family Policy and Inequalities in Health in Different Welfare States. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44:233–253. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain C, Bearman P. Risk as Social Context: Immigration Policy and Autism in California. Sociol Forum. 2011;26:215–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2011.01238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeucia M, Hirsch JS. State and Local Policies as a Structural and Modifiable Determinant of HIV Vulnerability Among Latino Migrants in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:800–807. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial Discrimination and Health among Asian Americans: Evidence, Assessment, and Directions for Future Research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:130–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural Racism and Health Inequties. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8:115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D, Smith J, Sood N. Legal Status and Health Insurance among Immigrants. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1640–1653. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusmano M. Undocumented Immigrants in the United States: US Health Policy and Access to Care, Undocumented Immigrants and Access to Health Care. The Hastings Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Rodriguez N, Capps R, Kabiri N. The Effects of Recent Welfare and Immigration Reforms on Immigrants’ Access to Health Care. Int Migr Rev. 2003;37:444–463. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, Henley E. A Call for Further Research on the Impact of State-Level Immigration Policies on Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1250–1254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71:742–751. doi: 10.1037/amp0000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M, Prins S, Flake M, Philbin M, Frazer S, Hagen D, Hirsch J. Immigration Policies and Mental Health Morbidity among Latinos: A State-Level Analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;174:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS. Labor migration, externalities and ethics: Theorizing the meso-level determinants of HIV vulnerability. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS. A Courtship after Marriage: Sexuality and Love in Mexican Transnational Marriages. University of California Press; 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS. American Arrivals: Anthropology Engages the New Immigration. School for American Research Press; Santa Fe: 2003b. Anthropologists, migrants, and health research: confronting cultural appropriateness; pp. 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld-Davis J. Trump Orders Mexican Border Wall to Be Built and Plans to Block Syrian Refugees. N Y Times 2017 [Google Scholar]

- House J, Schoeni R, Kaplan G, Pollack H. Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2008. The health effects of social and economic policy: the promise and challenge for research and policy; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N. In-state Tuition for the Undocumented: Education Effects on Mexican Young Adults. J Policy Anal Manage. 2008;27:771–792. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Kaestner R. Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:697–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kena G, Hussar W, McFarland J, De Brey C, Musu-Gillette L, Wang X, Zhang J, Rathbun A, Wilkinson-Flicker S, Diliberti M, Barmer A, Bullock Mann F, Dunlop Velez E. The Condition of Education 2016. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, D.C.: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk D, Papachristos A, Fagan J, Tyler T. The Paradox of Law Enforcement in Immigrant Communities: Does Tough Immigration Enforcement Undermine Public Safety? The Annals. 2012;641:79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer RJ, Hamilton AJ, Tolbert CJ. Does Policy Adoption Change Opinions on Minority Rights? The Effects of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage. Polit Res Q. 2014;67(4):795–808. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Chen J, Coull B, Waterman P, Beckfield J. The Unique Impact of Abolition of Jim Crow Laws on Reducing Inequities in Infant Death Rates and Implications for Choice of Comparison Groups in Analyzing Societal Determinants of Health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2234–2244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, Lopez MH. Hispanic Nativity Shift. Pew Res Cent Hisp Trends Proj 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Hatzenbuehler M. Stigma as an Unrecognized Determinant of Population Health: Research and Policy Implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41:653–673. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3620869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippel K. Workers describe the effect of the workers’ compensation process on their health: A Québec study. Int J Law Psychiatry, Special Issue: Work and Mental Health. 2007;30:427–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEowen R. Workers’ Compensation and the Exemption for Agricultural Labor, Cetner for Agricultural Law and Taxation. Iowa State University 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse A, Johnston A, Heisel H, Carter A, Lawrence M, Segreto J. State Omnibus Immigration Legislation and Legal Challenges. National Conference of State Legislatures; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morse A, Mendoza GS, Lam CW, German E. 2013 Immigration Report. National Conference of State Legislatures; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morse A, Soria Mendoza G, Mayorga J. Report on 2015 State Immigration Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moya EM, Shedlin MG. Policies and Laws Affecting Mexican-Origin Immigrant Access and Utilization of Substance Abuse Treatment: Obstacles to Recovery and Immigrant Health. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1747–1769. doi: 10.1080/10826080802297294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V, Muntaner C, Borrell C, Benach J, Quiroga A, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Verges N, Pasarin I. Politics and health outcomes. The Lancet. 2006;368:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes Health Disparities. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2007;64:101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D. Health Care Access Among Hispanic Immigrants: ¿Alguien Está Escuchando? [Is Anybody Listening?] NAPA Bull. 2010;34:47–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4797.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick S, Chen JH, Perreira K. Local-Level Immigration Enforcement and Food Insecurity Risk among Hispanic Immigrant Families with Children: National-Level Evidence. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J. Structural racism: building upon the insights of John Calmore. N C Law Rev. 2008;86:791–816. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, Song E, Alonzo J, Downs M, Lawlor E, Martinez O, Sun CJ, O’Brien MC, Reboussin BA, Hall MA. The Impact of Local Immigration Enforcement Policies on the Health of Immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:329–337. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Wu C. The Links Between Education and Health. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Sabo S, Lee A. The Spillover of US Immigration Policy on Citizens and Permanent Residents of Mexican Descent: How Internalizing “Illegality” Impacts Public Health in the Borderlands. Front Public Health. 2015;3:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo S, Shaw S, Ingram M, Teufel-Shone N, Carvajal S, Guernsey de Zapien J, Rosales C, Redondo F, Garcia G, Rubio-Goldsmith R. Everyday violence, structural racism and mistreatment at the US—Mexico border. Soc Sci Med. 2014;109:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas LM, Ayon C, Gurrola M. Estamos Traumados: The Effect of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment and Policies. J Community Psychol. 2013;41:1005–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2008:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- Santos CE, Menjívar C, Godfrey E. Effects of SB 1070 on Children. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2013. (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2335240). [Google Scholar]

- Senate Bill 1070. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Silva A. Undocumented Immigrants, Driver’s Licenses, and State Policy Development: A Comparative Analysis of Oregon and California. UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment; UCLA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Lopez MH, Passel J, Motel S. Unauthorized Immigrants: Length of Residency, Patterns of Parenthoo. PewResearchCenter; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teigen A, Morse A. Driver’s Licenses for Immigrants. National Conference of State Legislatures; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, Updegraff KA. Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 Immigration Law on Utilization of Health Care and Public Assistance Among Mexican-Origin Adolescent Mothers and Their Mother Figures. Am J Public Health. 2013;104:S28–S34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Wallace SP. Migration Circumstances, Psychological Distress, and Self-Rated Physical Health for Latino Immigrants in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1619–1627. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor. The National Agricultural Worker Survey 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med, Part Special Issue: Place, migration & health. 2012;75:2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Yeager VA, Menachemi N, Scarinci IC. Impact of Alabama’s Immigration Law on Access to Health Care Among Latina Immigrants and Children: Implications for National Reform. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:397–405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Collins C. US Socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annu Rev Sociol. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Winham D, Armstrong T. Nativity, Not Acculturation, Predicts SNAP Usage Among Low-income Hispanics With Food Insecurity. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2015;10:202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv TA, Lo B. Denial of Care to Illegal Immigrants — Proposition 187 in California. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1092–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.