Abstract

We assessed availability of antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) at nearly 4000 acute care hospitals enrolled in the National Healthcare Safety Network. In 2015, 95% offered any AFST, 28% offered AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, and 33% offered reflexive AFST. Availability of AFST improved from 2011 to 2015, but substantial gaps exist in the availability of AFST.

Keywords: antifungal agents, antifungal susceptibility testing, candidemia, laboratory practices, resistance

Candidemia is 1 of the most common health care–associated bloodstream infections in the United States [1]. Candida albicans, which accounted for the majority of invasive Candida infections in the past, now causes <40% of invasive Candida infections, while more drug-resistant species, such as Candida glabrata, account for one-third of all invasive Candida infections [2]. Nearly 7% of all Candida isolates collected through an active population-based surveillance system in the United States during 2008–2014 were resistant to fluconazole [3], and 12% of C. glabrata isolates collected during 2014 had elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to echinocandins [4].

The 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Candidiasis Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend echinocandins as the firstline treatment for all invasive Candida infections [5]. Given the rise in Candida spp. that tend to be drug resistant, including the emergence of Candida auris [6] and the rise in echinocandin resistance among C. glabrata, it is important that clinicians have access to antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) to make optimal treatment decisions. The IDSA treatment guidelines strongly recommend testing for azole susceptibility for all bloodstream and other clinically relevant Candida isolates and consideration of testing for echinocandin susceptibility on all C. glabrata and Candida parapsilosis isolates and any Candida isolates from patients who have had prior treatment with an echinocandin [5]. Availability of AFST allows clinicians to make better treatment decisions for patients and can aid in antifungal stewardship efforts by facilitating transitioning from an echinocandin to an azole when appropriate [7]. Important factors to consider with AFST are whether testing is sent to an outside laboratory or performed on site, and whether the susceptibility testing is conducted reflexively, especially when Candida is isolated from a sterile body site, or whether a clinician must order AFST. On-site testing substantially improves time to result (<3 days vs ~7 days when isolates need to be sent to an outside laboratory) [8], and reflexive testing has the potential to do the same. Understanding how much and what type of testing for antifungal susceptibility is occurring in the United States can help promote best practices and improve patient outcomes. Our objective was to assess AFST availability and practices reported in 2011 and 2015 by acute care hospitals enrolled in the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).

METHODS

We analyzed data from NHSN’s Patient Safety Component Annual Hospital Survey [9] that were completed for calendar years 2011 and 2015 as of October 1, 2016. Completion of the survey is required for all hospitals participating in the NHSN. Information collected included hospital medical school affiliation, bed size, microbiology laboratory practices, and questions regarding access to AFST, the location of the laboratory performing AFST (on-site, affiliated, or reference/commercial laboratory), and the specific testing methods used for AFST, as well as various hospital characteristics. The analysis included US acute care hospitals from whom survey responses were available with the exclusion of psychiatric, inpatient rehabilitation and long-term acute care facilities. McNemar’s test was used to assess changes between 2011 and 2015 in the availability of AFST among hospitals that reported in both 2011 and 2015. Hospital characteristics were examined in a multivariate analysis that included medical school affiliation, bed size, availability of AFST in the hospital’s own laboratory or an affiliated medical center, and rates of Candida central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) [10].

Candida CLABSI rates included CLABSIs in which at least 1 of the reported pathogens was a Candida species. Hospitals with numerator and denominator (central line day) data reported from ≥1 acute care inpatient location (excluding rehabilitation) performing in-plan CLABSI surveillance for ≥1 month during 2015 were included. The total number of Candida CLABSIs was divided by the corresponding total number of central line days in each hospital to obtain the hospital’s rate per 1000 central line days used in the analysis. Logistic regression was used for the multivariate modeling to assess which factors were associated with a hospital offering AFST in its own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center and reflexive AFST. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4).

RESULTS

A total of 4690 acute care hospitals participated in the NHSN’s Patient Safety Component Annual Hospital Survey in 2015, including 3438 (73.3%) general, 85 (1.8%) pediatric, and 17 (0.4%) oncology hospitals, and 856 critical access hospitals (18.3%). Of these, 4025 (85.8%) reported that they had a microbiology lab on-site or at an affiliated medical center to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and 1272 (31.6%) of these hospitals reported offering AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center. Overall, 95.5% (n = 4466) of the 4690 acute care hospitals offered any AFST, 28.4% (n = 1333) offered AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, and 32.5% (n = 1524) offered reflexive AFST. Pediatric (55.3%; n = 47/85) and oncology (64.7%; n = 12/17) hospitals more commonly offered AFST at their own laboratory or an affiliated medical center compared with general hospitals (28.0%; n = 964/3438). Reflexive AFST was offered by 33.0% (n = 1134/3438) of general hospitals, 57.6% (n = 49/85) of pediatric hospitals, and 70.6% (n = 12/17) of oncology hospitals. Broth microdilution (including YeastOne colorimetric microdilution) was the most common method used for AFST (56.0%; n = 2627/4690), followed by Vitek-2 (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France; 16.7%; n = 783/4690). Of the 773 hospitals that offered reflexive testing for echinocandins, 40.8% (n = 315) did so only for caspofungin and 37.9% (n = 293) offered testing for all 3 echinocandins, including anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin.

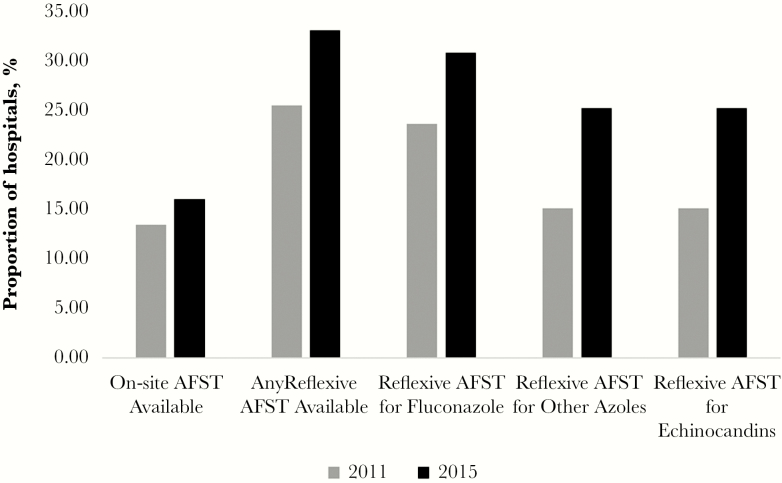

Three thousand nine hundred forty-seven hospitals completed the survey both in 2011 and 2015, allowing for comparison of AFST services between those years (Figure 1). The proportion of hospitals offering any AFST increased from 91.9% (n = 3629) in 2011 to 95.3% (n = 3763) in 2015 (P < .001). The proportion of hospitals offering AFST at their own hospital or an affiliated medical center increased from 26.2% (n = 1035) to 28.4% (n = 1121; P < .001), and hospitals offering reflexive AFST increased from 25.5% (n = 1005) to 33.1% (n = 1308; P < .001). Availability of reflexive AFST for echinocandins increased from 12.7% (n = 502) to 23.0% (n = 909) of hospitals between 2011 and 2015 (P < .001); reflexive AFST for fluconazole increased from 23.6% (n = 933) to 30.8% (n = 1217) during this period (P < .001).

Figure 1.

Comparison of availability of antifungal susceptibility testing availability in the hospital’s own laboratory or affiliated medical center and reflexive antifungal susceptibility testing in 2011 and 2015 among acute care hospitals enrolled in National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) that reported to the NHSN Patient Safety Component Annual Hospital Survey in both years (n = 3947). AFST, antifungal susceptibility testing.

Because general acute care hospitals represented the largest group of hospitals, we assessed characteristics of hospitals with complete survey and Candida CLABSI data reported to NHSN in 2015 (3357 of 3438 hospitals) (Table 1). Overall, 28.3% (n = 951/3357) of general acute care hospitals offered AFST at their laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, and 33.3% (n = 1119/2257) offered reflexive AFST. Thirty-eight percent (n = 440/1152) of general acute care hospitals with a medical school affiliation offered AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, compared with 23.2% (n = 511/2205) of those without a medical school affiliation. Twenty-five percent (n = 294/1162) of hospitals with ≤100 beds offered reflexive testing compared with 60.0% (n = 150/250) of hospitals with >500 beds. Twenty-two percent (n = 449/2017) of hospitals with a Candida CLABSI rate of 0 (ie, reported no CLABSIs caused by Candida in 2015) offered AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, and 27.5% (n = 554/2017) offered reflexive AFST; among hospitals with a non-0 Candida CLABSI rate in 2015, 37.5% (n = 502/1340) offered AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center, and 42.2% (n = 565/1340) offered reflexive AFST. Factors significantly associated with offering AFST at the hospital’s own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center were having a medical school affiliation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23–1.74) and having a non-0 Candida CLABSI rate (aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16–1.71). Higher numbers of hospital beds were associated with progressively greater odds (up to an aOR of 3.23; 95% CI, 2.28–4.59; for hospitals with >500 beds compared with hospitals with hospitals with ≤100 beds). Factors significantly associated with offering reflexive AFST included having AFST available at the hospital’s own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center (aOR, 9.61; 95% CI, 8.06–11.50), having a medical school affiliation (aOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.03–1.51), having a non-0 Candida CLABSI rate (aOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.00–1.52), and higher bed size (>500 beds: aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.17–2.57; compared with ≤100 beds).

Table 1.

General Hospital Characteristics and Types and Locations of AFST Reported to the National Health Safety Network Patient Safety Component Annual Hospital Survey in 2015

| Automatic or Reflexive Testing, % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. of Hospitals a | Any AFST Offered, No. (%) |

AFST Offered at the Hospital’s Own Laboratory or at an Affiliated Medical Center,

No. (%) |

Reflexive AFST Offered,

No. (%) |

Fluconazole, No. (%) |

Other azoles,

No. (%) |

Echinocandins,

No. (%) |

| Medical school affiliation | |||||||

| Yes | 1152 | 1118 (97.0) | 440 (38.2) | 493 (42.8) | 464 (40.3) | 385 (33.4) | 348 (30.2) |

| No | 2205 | 2088 (94.7) | 511 (23.2) | 626 (28.4) | 586 (26.6) | 465 (21.1) | 425 (19.3) |

| Number of beds | |||||||

| 0–100 | 1162 | 1106 (95.2) | 227 (19.5) | 294 (25.3) | 268 (23.1) | 207 (17.8) | 192 (16.5) |

| 101–200 | 903 | 858 (95.0) | 247 (27.4) | 286 (31.7) | 266 (29.5) | 223 (24.7) | 201 (22.3) |

| 201–500 | 1042 | 994 (95.4) | 333 (32.0) | 389 (37.3) | 375 (36.0) | 305 (29.3) | 272 (26.1) |

| >500 | 250 | 248 (99.2) | 144 (57.6) | 150 (60.0) | 141 (56.4) | 115 (46.0) | 108 (43.2) |

| Laboratory | |||||||

| Hospital has own laboratory or affiliated medical center that performs AFST | 951 | 951 (100.0) | N/A | 673 (70.8) | 642 (67.5) | 506 (53.2) | 484 (50.9) |

| Hospital offers AFST via nonaffiliated or commercial laboratory | 2406 | 2255 (93.7) | N/A | 446 (18.5) | 408 (17.0) | 344 (14.3) | 289 (12.0) |

| Candida CLABSI rate per 1000 central line days | |||||||

| 0 | 2017 | 1914 (94.9) | 449 (22.3) | 554 (27.5) | 518 (25.7) | 418 (20.7) | 383 (19.0) |

| Non-0 | 1340 | 1292 (96.4) | 502 (37.5) | 565 (42.2) | 532 (39.7) | 432 (32.2) | 390 (29.1) |

Abbreviations: AFST, antifungal susceptibility testing; CLABSI, central line–associated bloodstream infection.

a3357 of 3438 hospitals (97.6%) had complete survey data and Candida CLABSI rate data from 2015.

DISCUSSION

Using a data set that represents a majority of US acute care hospitals, we found that in 2015 nearly all hospitals reported offering AFST, but only approximately 1 in 4 hospitals offered AFST services at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center and 1 in 3 offered reflexive AFST. Although nearly all hospitals reported having microbiology labs at their own hospital or at an affiliated medical center, only about one-third had access to AFST in these locations. It is encouraging that the proportion of hospitals with access to AFST increased from 2011 to 2015 and that a substantial proportion of hospitals that serve neonates and patients with malignancies, who are among the highest-risk groups for invasive and drug-resistant Candida infections, offer AFST at their own laboratory or at an affiliated medical center and offer reflexive AFST. Large general hospitals with medical school affiliations also appear to be more likely to have AFST services. Notably, over half of hospital laboratories reported using broth microdilution, the gold standard for fungal susceptibility testing.

A substantial gap still exists in availability of AFST services. Two-thirds of general acute care hospitals that had a non-0 Candida CLABSI rate, meaning they had reported some episodes of candidemia during 2015, reported using commercial or reference laboratories for AFST, and over half did not provide reflexive AFST. Reflexive AFST remains an unmet need at many hospitals, especially for echinocandin susceptibility testing given increasing use as firstline therapy and growing echinocandin resistance [4].

Barriers to having AFST services at the hospital’s own laboratory may include lack of personnel trained in mycology, low isolate volume to justify maintaining a mycology laboratory, costs associated with AFST, and not recognizing the importance of obtaining AFST results quickly. Further exploration of these factors is needed to help expand AFST access in the future. Hospitals using commercial or reference laboratories for AFST services could consider requesting reflexive testing of Candida species isolated from selected specimen types or for selected species, consistent with IDSA treatment guideline recommendations. AFST results are all the more important now for the management of Candida infection given the recent emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris infections [11] and echinocandin-resistant C. glabrata [4]. Expansion of AFST services could not only improve care of patients with candidemia but also improve care of patients with other fungal diseases such as invasive aspergillosis, for which voriconazole resistance is an emerging concern [12].

Our findings are based on self-reported data from hospital personnel, and no verification of AFST availability was conducted. However, these data remain the most comprehensive available on the subject. Because of the wording of the questions in the survey, we could not reliably distinguish between on-site AFST availability and AFST performed at an affiliated medical center. Additionally, it is possible that AFST availability varies by Candida species (eg, C. glabrata may be more likely to be tested), and this level of detail was not available in the survey.

Improved access to timely and accurate AFST is needed, particularly in hospitals with high rates of invasive Candida infections. Access to these services may increase as laboratories and clinicians adopt the 2016 IDSA guidelines to perform AFST on all clinically relevant Candida isolates. To have the maximum impact on antifungal stewardship practices and patient outcomes, clinician education on selecting appropriate therapy for particular fungal species based on resistance profiles should be accompanied by expansion of AFST services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Edwards, Maggie Dudeck, and Daniel Pollock. The authors have no reported conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W et al. . Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH et al. . Changes in incidence and antifungal drug resistance in candidemia: results from population-based laboratory surveillance in Atlanta and Baltimore, 2008–2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cleveland AA, Harrison LH, Farley MM et al. . Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas, 2008–2013: results from population-based surveillance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vallabhaneni S, Cleveland AA, Farley MM et al. . Epidemiology and risk factors for Echinocandin nonsusceptible Candida glabrata bloodstream infections: data from a large multisite population-based Candidemia Surveillance Program, 2008–2014. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR et al. . Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vallabhaneni S, Kallen A, Tsay S et al. . Investigation of the first seven reported cases of Candida auris, a globally emerging invasive, multidrug-resistant fungus—United States, May 2013–August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah DN, Yau R, Weston J et al. . Evaluation of antifungal therapy in patients with candidaemia based on susceptibility testing results: implications for antimicrobial stewardship programmes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pai MP, Pendland SL. Antifungal susceptibility testing in teaching hospitals. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CfDCaP (CDC). Patient safety component-annual hospital survey. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/forms/57.103_pshospsurv_blank.pdf. Accessed 10 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. CfDCaP (CDC). Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line-associated bloodstream infection). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf. Accessed 10 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsay S, Welsh RM, Adams EH et al. . Notes from the field: ongoing transmission of Candida auris in health care facilities—United States, June 2016–May 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:514–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiederhold NP, Gil VG, Gutierrez F et al. . First detection of TR34 L98H and TR46 Y121F T289A Cyp51 mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:168–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]