The British HIV Association and the International AIDS Society ran the first joint symposium in an IAS conference. It covered a range of clinical and epidemiological topics and examined the current challenges and opportunities in implementing services within financial constraints. Four outstanding speakers gave overviews that are summarised below.

UK epidemiology and treatment cascade

Valerie Delpech

Public Health England

The United Kingdom provides free healthcare for all people diagnosed with HIV infection through 200 or so specialised HIV outpatient clinics. Monitoring of HIV care is undertaken by Public Health England using comprehensive data routinely collated from all HIV clinics.

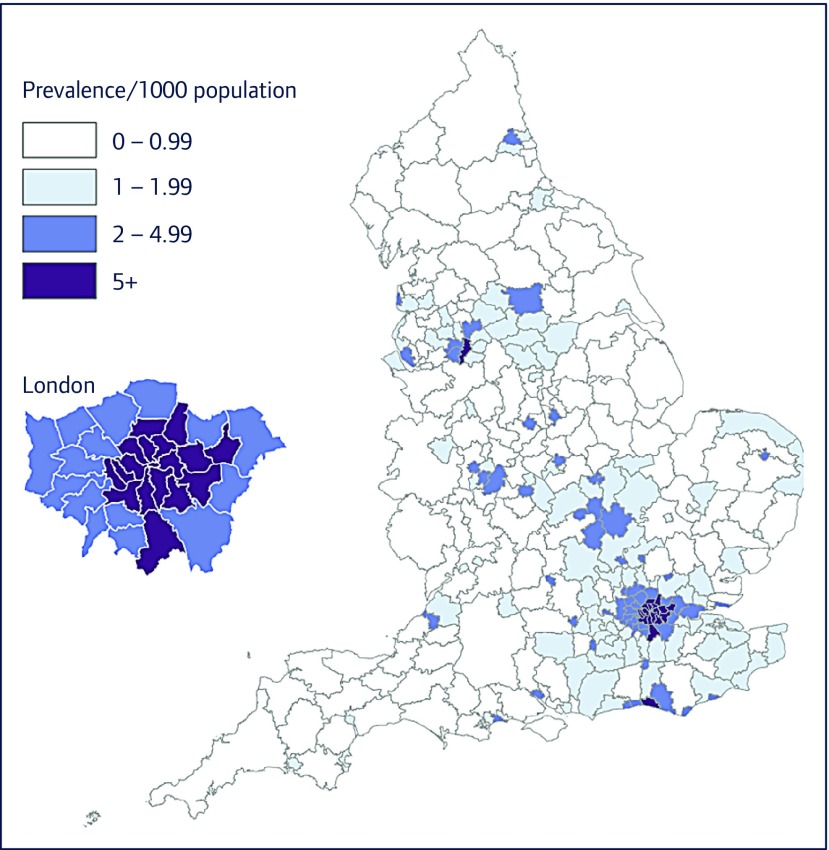

In 2015, an estimated 101,200 people (95% credible interval (CrI) 97,500–105,700) were living with HIV in the UK. This is equivalent to an HIV prevalence of 1.6 per 1000 individuals, or 0.16% (Figure 1). Of concern, 13,500 (95% CrI 10,200–17,800), or 13% (95% CrI 10–17%) people remain unaware of their infection and are at risk of passing on the virus to others. The new diagnosis rate remains high, driven by ongoing transmission and sustained testing. In 2015, 6095 people were diagnosed with HIV: this represents a new diagnosis rate of 11.4 per 100,000 individuals, which is higher than most other countries in Western Europe, the average being 6.3 per 100,000 people in 2015.

Figure 1.

Diagnosed HIV prevalence (per 1000 population aged 15–59 years): England, 2015. Overall prevalence rate: 2.26 (2.24–2.27) per 1000. (From Public Health England).

Over 95% of all people living with HIV (PLWH) in the UK have most likely acquired their infection through sexual contact, around half of whom are heterosexuals and half were gay/bisexual men. Although less common as a route of HIV exposure, transmission continues among people who inject drugs (PWID).

Overall in 2015, 47,000 (95% CrI 44,200–50,900) gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM) were estimated to be living with HIV, of whom 5800 (95% CrI 3200–9600), or 12% (95% CrI 7–19%) remained undiagnosed. HIV incidence (the number of new infections) remains particularly high in this group. In England an estimated 2800 (95% CrI 1700–4400) gay/bisexual men acquired HIV in 2015, with the vast majority acquiring the virus within the UK.

HIV care in the UK is of a high standard for all. In 2015, 88,769 people received HIV care, up 73% from a decade ago (51,449 in 2006). This reflects the longer life expectancy conferred by effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), as well as consistent numbers of people newly diagnosed. Nearly all (97%) of the 6095 people diagnosed with HIV in 2015 were linked to specialist HIV care within 3 months of diagnosis, similarly to previous years. Furthermore, the vast majority (94%) of people accessing HIV care in 2015 were receiving ART and as a result have undetectable virus in blood and body fluids and are, therefore, very unlikely to transmit HIV to others. These indicators are monitored at the trust level on the National Health Service in England (NHSE) HIV clinical dashboard and indicate high quality of service throughout the country. Furthermore, epidemiological markers show that there is no indication of inequalities in HIV care received through the NHS by gender, ethnicity or HIV exposure. All subpopulations of PLWH have reached the UNAIDS targets of 90% diagnosed on ART and 90% with viral load suppression for those on ART. However, late presentation at diagnosis remains high and highlights the need for increased and expanded HIV testing. In 2015, 39% of adults were diagnosed at a late stage of infection.

New diagnoses in 2016 were considerably lower than in 2015, particularly among gay and bisexual men. This was due to high volumes of testing, initiation of early treatment following BHIVA treatment as prevention recommendations and the use of internet-based pre-exposure prophylaxis. We need to consolidate the scaling-up of testing and early commencement of ART across all parts of the country for all groups at greatest risk of HIV.

Prevention: supporting generic PrEP access and offering monitoring – legalities and practicalities. Efficiencies viewed through 90:90:90

Nneka Nwokolo

56 Dean Street, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital

No single HIV prevention initiative has proved to be effective so far. The most successful strategies have been where a combination of interventions has been adopted.

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), in association with other modalities such as treatment as prevention (TasP), have been shown to be the likely reasons for reductions in new HIV infections seen in San Francisco [1] and London [2].

However, PrEP is not available on the NHS in England, thereby forcing individuals to purchase generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) online. Generic formulations purchased via www.iwantprepnow.co.uk have been established to be genuine [3]; however, it is crucial that individuals purchasing PrEP online are screened appropriately for HIV, hepatitis B and C, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as well as undergoing assessment of their renal function.

The 56 Dean Street Clinic has provided monitoring for individuals purchasing generic PrEP since February 2016. With 336 person-years of follow-up, no new HIV or hepatitis infections have been diagnosed, although there was a 10% increase in STIs at follow-up. No significant deteriorations in renal function were seen [4].

In areas where PrEP is unavailable, it is crucial that HIV and sexual health services support individuals on generic PrEP by ensuring that they have access to monitoring. Several international PrEP guidelines exist and clinicians should familiarise themselves with guidance relevant to their clinical circumstances/country.

Concerns remain about STI risks in individuals on PrEP. However, data on risk compensation are conflicting [5–7] and efforts should continue to address these issues.

The England experience: commissioning and prescribing efficiencies

Laura Waters

Mortimer Market Centre

In the UK, like many other parts of the world, we are seeing increasing numbers of people accessing HIV care driven by a steady stream of new diagnoses and improved life expectancy for treated individuals [1, 2]. Despite falling short of the first UNAIDS ‘90’, with 87% of all people living with HIV estimated to be diagnosed, we have demonstrated excellent outcomes for the subsequent cascade elements with 96% of diagnosed people on ART and 94% of those suppressed [3]. Medical services are devolved in the UK and the focus of the presentation was England, which accounts for over 90% of all diagnosed HIV in the UK [3].

There are a number of mechanisms to fund healthcare, including taxation, private and social health insurance and direct user charges; NHSE is funded almost entirely by taxation [4]. Regardless of the system used, all countries face similar challenges of meeting rising medical demand from ageing populations in the face of financial pressures. Between 2012 and 2015, most NHS providers in England moved from a position of financial surplus to one of deficit [5] and, if UK healthcare spending was to keep pace with the average spending of the other 14 original European Union members we are facing an estimated $43 billion shortfall by 2020/21 [6].

The introduction of the Health & Social Care Act in England in 2012 saw the biggest re-organisation of the NHS since its inception and divided healthcare responsibility into three streams:

-

(1)

Local authorities: commissioning responsibility includes sexual health, drug/alcohol services and most HIV testing.

-

(2)

NHSE: commissions specialised services at a national level, including HIV treatment/care and drugs for HIV prevention plus antenatal HIV screening.

-

(3)

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs): groups of primary care providers that are responsible for commissioning almost everything else and some HIV testing.

In terms of HIV care this means that all new antiretrovirals (ARVs) from Stribild onwards require a separate NHSE commissioning policy post-licensing and that all HIV commissioning regions are expected to produce and follow cost-based prescribing policies with the use of generics prioritised over pill burden if the patient is willing to switch. The NHSE policy for tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) has attracted much discussion; essentially TAF-based products are restricted to those with renal or bone issues where tenofovir DF and abacavir are not optimal [7]. This approach is supported by cohort data that demonstrates a very low risk of kidney impairment amongst TDF-treated individuals who have a low predicted risk of CKD [8]. Commissioning levers are also applied, whereby a proportion of funding is withheld if pre-agreed targets are not met, for example, limiting the proportion of people undergoing CD4 testing. In addition NHS England has introduced targets for switching ARVs based on costs; examples include a target to switch 60% of individuals on Atripla to Truvada and generic efavirenz and to switch 95% of people on Kivexa to generic abacavir/lamivudine. This switch programme has achieved savings of £32 million over 2 years, £15 million from Kivexa switches alone (NHS England, personal communication).

Ultimately all HIV services face rising demand and increasing proportions of patients with age-related comorbidities and complexities, most in the face of tightened budgets. As long as we continue to consider the ethical principles of medical care and ensure that the quest for justice does not ignore the importance of autonomy, then we can prescribe based on cost, yet also do the best for the patients under our care. We must remember, after all, that our world class outcomes and impressive life expectancy figures are based on drugs that many guidelines would consider 'old'.

Tougher times: adapting to increasing demand with declining resources. The patient perspective

Angelina Namiba

Salamander Trust

In order to ensure that the presentation was representative and not just informed by one patient voice, I have conducted a mini ‘qualitative survey’ with people living with HIV. Responses were received from 12 women and five men living with HIV. I asked them the question about what, from their perspective as patients, could be done to adapt to increasing demand with diminishing resources.

There were varying responses including one where the recommendation was to, ‘overthrow the Tory government and tax multinationals to get resources to fund health and social care.’ The other responses fell into four main themes:

-

•

Investment in structured peer support to compliment clinical care.

-

•

DIY. They felt that as patients, they had the skills and expertise to do a lot in terms of their own care as well as in supporting peers. This was important to enable patients to not feel so completely reliant on the system.

-

•

Organisational collaboration. Not just between HIV charities, but also between HIV charities and those working with patients in other disease areas.

-

•

Effective use of modern technology. Particularly for patients who are responding well to ARVs and have no other health issues.

In summary, patients felt that, whatever the cost savings, it was important to not to lose sight of the fact that:

-

•

All services/initiatives need to be embedded in, and informed by community.

-

•

They also had a caution around the message that ‘we can do it all ourselves’, as it washes responsibility off the government's hands.

-

•

Community-based services and mobilisation are most effective as part of a well-funded NHS; a good education system and a compassionate society that doesn't blame, but encompasses those who face health and social care inequalities.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the UK is doing extremely well in terms of meeting the UNAIDS targets of 90-90-90. However, in order to achieve a ‘truly 360 degree view’, we need to move beyond viral suppression by adding a fourth ‘90’ to the treatment continuum: one that is about ensuring good quality of life for patients living with HIV.

References

- 1. Buchbinder S, Packer T.. Getting to zero: an update. Available at: www.gettingtozerosf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GTZ_Health-Commission_02MAY17_From-HC-website.pdf ( accessed September 2017).

- 2. Brown A, Mohammed H, Ogaz D et al. Fall in new HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men (MSM) at selected London sexual health clinics since early 2015: testing or treatment or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? Euro Surveill 2017; 22: 30553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang X, et al. InterPrEP: internet-based pre-exposure prophylaxis with generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine in London – analysis of pharmacokinetics, safety and outcomes. HIV Med 2017; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aloysius I, Savage A, Zdravkov J et al. InterPrEP. Internet-based pre-exposure prophylaxis with generic tenofovir DF/emtricitabine in London: an analysis of outcomes in 641 patients. J Virus Erad 2017; 3: 218– 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B et al. On-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2237– 2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 53– 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 1601– 1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2103: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2017; 4: e349– e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2014; 28: 1193– 1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirwan PD, Chau C, Brown AE et al. HIV in the UK. 2016 report. December 2016. Public Health England, London Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/hiv-in-the-united-kingdom ( accessed September 2017).

- 4. McKenna H, Dunn P, Northern E, Buckley T.. How health care is funded. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/how-health-care-is-funded ( accessed September 2017).

- 5. Health Foundation Chart: the changing geography of NHS deficits. Available at: www.health.org.uk/chart-changing-geography-nhs-deficits ( accessed September 2017).

- 6. Appleby J. How does NHS spending compare with health spending internationally? Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2016/01/how-does-nhs-spending-compare-health-spending-internationally ( accessed September 2017).

- 7. Specialised Commissioning Team, NHSE Clinical Commissioning Policy: Tenofovir alafenamide for treatment of HIV 1 in adults and adolescents. Reference: NHS England: 16043/P. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/f03-taf-policy.pdf ( accessed September 2017).

- 8. Flandre P, Pugliese P, Allavena C et al. Does first-line antiretroviral regimen impact risk for chronic kidney disease whatever the risk group? AIDS 2016, 30: 1433– 1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]