Introduction

Few young children consume recommended level of fruits and vegetables.1 High quality preschool programs often provide food experiences to expose children to healthy food options.2,3 However, personal experiences of early childhood educators may inhibit their ability to create a nurturing environment at mealtime and to educate children about nutritious foods. Together, We Inspire Smart Eating (WISE) was developed to support educators of young children4–14. The WISE curriculum is intended to be used in weekly food experiences in preschool such as Head Start and schools using the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP).15

The intervention, WISE, was designed to establish healthy early eating habits for children 3 to 8 years old. The intervention includes 3 key components: (a) a classroom curriculum, (b) educator training, and (c) parent education using materials for outreach. This report presents a brief summary of the development of the components of WISE. Change in nutrition knowledge of educators across time was examined. Sustainable knowledge is critical given that knowledge and awareness are necessary prerequisites for adoption of new behaviors.16,17 This report provides the foundation for later, more detailed process and impact evaluations of WISE. All activities in the project were approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences institutional review board.

Summary of Development

The development of WISE was based on USDA recommendations18 combined with concepts of the socio-ecological model.19 After an extensive literature review, WISE curriculum components were developed to be consistent with the research-based evidence of nutrition promotion for children. Further, components were aligned with state regulations, national standards, and recommendations from experts (e.g., American Pediatric Association). In the development of the classroom curriculum, classroom observations and in-person conversations with educators provided targets for educator training.20 For example, educators often pressured children to consume food regardless of hunger cues, they typically failed to model intake of healthy foods, and they discouraged manipulation of new foods.20 These attitudes often stem from a teacher’s personal history with food.21 Many educators lacked food as children, and 33% indicated current food insecurity.14

This formative work provided the basis of educator training targeting use of hunger cues, modeling healthy food consumption, and guiding children in sensory food experiences. WISE was structured to reduce educator time to meet existing educational requirements and be budget-sensitive. In the development of WISE parent education and outreach materials, secondary analyses of data from low-income families were analyzed.6 This informed the method and content of the parent education component.

The Curriculum

Classroom Curriculum

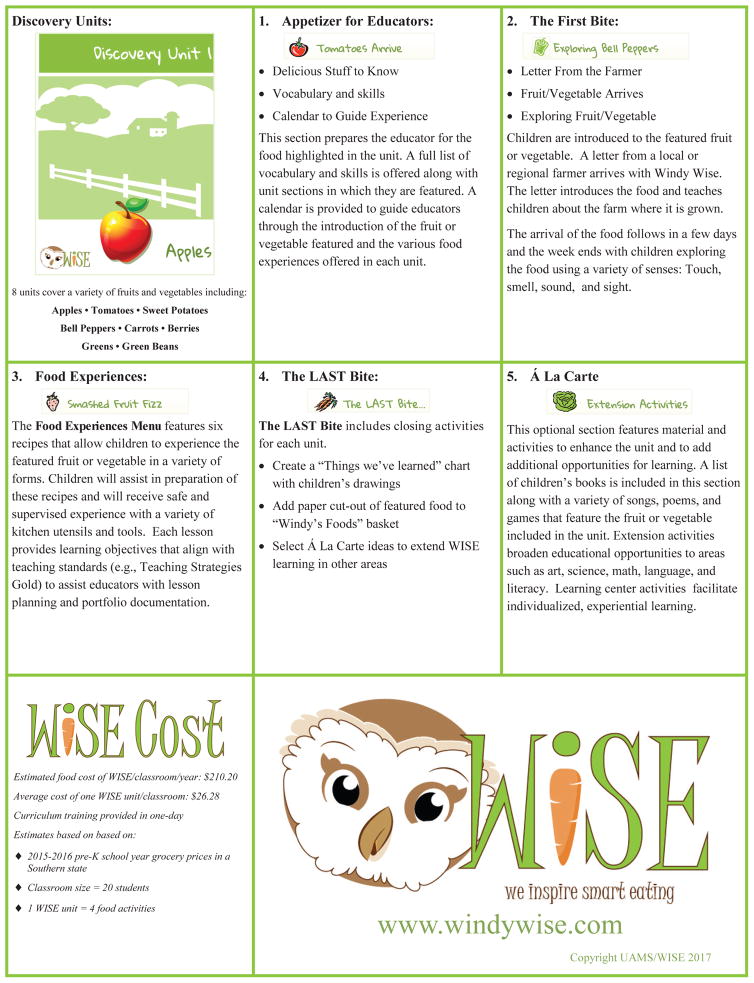

In an extensive manual, WISE is organized with 8 monthly Discovery Units as listed in Figure 1, Discovery Units. Figure 1 describes 5 steps found in each Unit. Each Unit provides background ‘Appetizer’ education (Step 1). The month begins with a farmer letter and the arrival of the food. The curriculum mascot, Windy Wise, is a barn owl puppet who “travels” between the classroom and farm to deliver farm news. Food is introduced with sensory exploration (Step 2).

Figure 1.

For the remainder of the month, educators select food activities for weekly hands-on food interactions in small groups (Step 3). The primary objective is to maximize children’s interaction with foods. Materials support the integration of WISE into other educational activities (e.g., math). Each month includes closing activities to transition to the next food (Steps 4 and 5). Foods introduced early in the school year recur as companion ingredients in later months.

Educator Training

Training for educators consists of an interactive 6-hour training based on adult learning theories22,23 and includes active instruction, monitoring, and feedback. In training, educators explored their role in child nutrition, discussed food attitudes and beliefs, practiced using WISE, and practiced using resources to connect with and educate families. Post training, educators reported learning new information (98%), understanding the goals of WISE (100%), holding the view that WISE would be useful (100%), and feeling prepared to implement WISE (100%).

Parent Engagement

Parents received ‘back pack’ letters from the farmer. Based on behavioral economics theory, the puppet mascot activities were used to excite children24 to increase the likelihood information from WISE would transfer to the home. Parent education was facilitated with an invitation to join a public WISE Facebook page where Windy provided ongoing posts related to the curriculum and nutrition for families with low resources and young children.

Educator Nutrition Knowledge

WISE was implemented (2015–16) in 20 Head Start classrooms, 13 Kindergarten, and 15 First Grade classrooms (N = 48 classroom with 56 educators). Nutrition knowledge of educators was assessed using an investigator-developed, 8-item nutrition knowledge survey 4 times: before and after training, about 2 months after implementation and at the end of the school year (internal consistency ranged from .68 to .71 depending on assessment). Repeated measures ANOVA of 50 (89%) complete cases indicated that knowledge differed statistically across the year (F(3,47)=30.21, p < .000) with post training increase sustained up to 9 months after training.

Discussion

WISE was developed with an extensive research foundation and grounding in the evidence base of the disciplines of nutrition, obesity prevention, early childhood, and adult learning styles. WISE was specifically designed for programs serving high-risk children from resource-poor backgrounds but may have the potential for transfer to other settings. This study demonstrated that WISE can be successfully integrated into existing Head Start and Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP) programs with associated significant and sustained changes in educator nutrition knowledge over the school year. However, it should be noted that the internal consistency of the assessment varied from less than adequate (.68) to adequate (.71). Support from educators for the curriculum was high after training and at the end of the year. The evaluation of WISE is ongoing and will include additional examination of the consumption of fruits and vegetables by preschool children, parent perceptions of WISE, and educator views of classroom components. Ongoing evaluation results, details on the cost and acquisition of WISE can be found in Figure 1 and at http://windywise.com/. In addition, new studies will fund the examination of how varied implementation approaches affect classroom use of the WISE curriculum and improve to child outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2011-68001-30014 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and by the Translational Research Institute (TRI), grants UL1TR000039 and KL2TR000063 through the NIH National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grimm K, Kim S, Yaroch A, Scanlon K. Fruit and vegetable intake during infancy and early childhood. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Supplement 1):S63–S69. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Accessed February 13, 2017];Subchapter B—The Administration for Children and Families, Head Start Program | ECLKC. http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/45-cfr-chap-xiii.

- 3.Head Start: National Center on Health. Health Services Newsletter: Family Style Means. Natl Cent Heal. 2015;3(3) https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/tta-system/health/docs/health-services-newsletter-201503.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swindle T. Setting the TABLE: Teaching and Bringing Nutrition Learning to Early Education. In. Poster Presented to Translational Science; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swindle T, Kyzer A, Johnson D, Whiteside-Mansell L. Identifying family nutritional deficiencies: The usefulness of the Family Map Health Module. In. The 38th Annual Head Start Conference; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward W, Swindle T, Kyzer A, Whiteside-Mansell L. Low Fruit/Vegetable Consumption in the Home: Cumulative Risk Factors in Early Childhood. Early Child Educ J. 2015;43(5):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s10643-014-0661-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swindle T, Whiteside-Mansell L, McKelvey L. Food insecurity: Validation of a two-item screen using convergent risks. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22(7):932–941. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9652-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swindle T, Ward W, Whiteside-Mansell L, Brathwaite J, Bokony P, Conners-Burrow N, McKelvey L. Pediatric Nutrition Parenting Impacts Beyond Financial Resources. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013 doi: 10.1177/0009922813505904.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteside-Mansell L, Swindle T, Swanson M, Bradley R, Ward W, McKelvey L, Burrow N. Early Predictors of Long-term Obesity Development In Impoverished Families. In. 2009 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Seattle, WA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swindle TM, Whiteside-Mansell L, McKelvey L. Food Insecurity: Validation of a Two-Item Screen Using Convergent Risks. J Child Fam Stud. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9652-7.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swindle TM, Ward WL, Whiteside-Mansell L, Bokony P, Pettit D. Technology Use and Interest Among Low-Income Parents of Young Children: Differences by Age Group and Ethnicity. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.06.004.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward WL, Swindle Taren M, Kyzer AL, Whiteside-Mansell L. Low Fruit/Vegetable Consumption in the Home: Cumulative Risk Factors in Early Childhood. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10643-014-0661-6.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swindle T, Ward WL, Whiteside-Mansell L, Brathwaite J, Bokony PA, Conners-Burrow N, McKelvey LM. Pediatric nutrition: Parenting impacts beyond financial resources. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014;53:793–795. doi: 10.1177/0009922813505904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swindle TM, Ward WL, Bokony P, Whiteside-Mansell L. A Cross-Sectional Study of Early Childhood Educators’ Childhood and Current Food Insecurity and Dietary Intake. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2016 Dec;:1–15. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2016.1227752.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evaluation of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program. Food and Nutrition Service; [Accessed March 16, 2017]. https://www.fns.usda.gov/evaluation-fresh-fruit-and-vegetable-program. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heller LJ, Skinner CS, Tomiyama AJ, et al. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change; pp. 1997–2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Heal Educ Behav. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKinnon C, Baker S, Auld G, et al. Identification of Best Practices in Nutrition Education for Low-Income Audiences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(4):S152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronfenbrenner U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. 2005 https://books.google.com/books?hl=en%7B&%7Dlr=%7B&%7Did=fJS-Bie75ikC%7B&%7Doi=fnd%7B&%7Dpg=PT7%7B&%7Ddq=Making+human+beings+human%7B&%7Dots=QwjKwP3MXr%7B&%7Dsig=kgAaRcl5ZtTuwPDY6N%7B_%7DJ%7B_%7DbtFNG0.

- 20.Swindle T, Whiteside-Mansell L. Educator Interactions at Head Start Lunches: A Context for Nutrition Education. [Accessed February 16, 2016];FASEB J. 2015 29(1 Supplement):731–732. http://www.fasebj.org/content/29/1_Supplement/731.2.short. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteside-Mansell L, Johnson D, Bokony P, McKelvey L, Burrow N, Swindle T. Using the Family Map: Supporting Family Engagement with Parents of Infants and Toddlers. Special Issue on Parent Involvement and Engagement in Head Start for Dialog. Res J Early Child F. 2013;16(1):20–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaslow M, Tout K, Halle T, Whittaker JV, Lavelle B. Toward the Identification of Features of Effective Professional Development for Early Childhood Educators. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine SL. Translating adult development research onto staff development practices. J Staff Dev. 1985;6(1):6–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cravener TL, Schlechter H, Loeb KL, et al. Feeding Strategies Derived from Behavioral Economics and Psychology Can Increase Vegetable Intake in Children as Part of a Home-Based Intervention: Results of a Pilot Study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(11):1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]