Abstract

CAPA peptides, such as periviscerokinin (PVK), are insect neuropeptides involved in many signaling pathways controlling, for example, metabolism, behavior, and reproduction. They are present in a large number of insects and, together with their cognate receptors, are important for research into approaches for improving insect control. However, the CAPA receptors in the silkworm (Bombyx mori) insect model are unknown. Here, we cloned cDNAs of two putative CAPA peptide receptor genes, BNGR-A27 and -A25, from the brain of B. mori larvae. We found that the predicted BNGR-A27 ORF encodes 450 amino acids and that one BNGR-A25 splice variant encodes a full-length isoform (BNGR-A25L) of 418 amino acid residues and another a short isoform (BNGR-A25S) of 341 amino acids with a truncated C-terminal tail. Functional assays indicated that both BNGR-A25L and -A27 are activated by the PVK neuropeptides Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2, leading to a significant increase in cAMP-response element–controlled luciferase activity and Ca2+ mobilization in a Gq inhibitor–sensitive manner. In contrast, BNGR-A25S was not significantly activated in response to the PVK peptides. Moreover, Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 directly bound to BNGR-A25L and -A27, but not BNGR-A25S. Of note, CAPA-PVK–mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and receptor internalization confirmed that BNGR-A25L and -A27 are two canonical receptors for Bombyx CAPA-PVKs. However, BNGR-A25S alone is a nonfunctional receptor but serves as a dominant-negative protein for BNGR-A25L. These results provide evidence that BNGR-A25L and -A27 are two functional Gq-coupled receptors for Bombyx CAPA-PVKs, enabling the further elucidation of the endocrinological roles of Bom-CAPA-PVKs and their receptors in insect biology.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), neuropeptide, receptor internalization, signaling, calcium, internalization, periviscerokinin (PVK)

Introduction

Insect neuropeptides form a very important group of signaling molecules that play central roles in regulating metabolism, homeostasis, development, reproduction, behavior, and many other physiological processes (1). The insect neuropeptide clusters characterized by a distinct FXPRXamide C-terminal motif constitute one of the most studied neuropeptide families in insects, comprising cardioacceleratory peptide 2b (CAP2b)5/periviscerokinin (PVK)/pyrokinin (PK), pheromone biosynthesis–activating neuropeptide (PBAN), diapause hormone, ecdysis-triggering hormone, β- and γ-subesophageal neuropeptides, and some myotropins (2, 3). As a very important member of the FXPRXamide neuropeptide family, the first insect CAPA-related peptide was identified from Manduca sexta and showed cardioactive activity (4). Further studies have demonstrated that CAPA peptides are synthesized in median neurosecretory neurons of abdominal ganglia and released into hemolymph (5). The insect CAPA peptides have been shown to promote fluid secretion from Malpighian tubules in different insect species (3, 6). In contrast, CAPA-2 peptides were found to act as antidiuretic hormones in the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (7).

Neuropeptides exert their biological function through receptors present on the cell surface. The Drosophila melanogaster orphan G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) CG14575, which is evolutionarily related to the human neuromedin U receptor (8), was first identified as a cognate receptor for the CAPA peptides by two separate research groups (9, 10). Subsequently, CAPA receptors have been identified and characterized from D. melanogaster (11), Anopheles gambiae (12), R. prolixus (13), and Rhipicephalus microplus (14, 15). The gene sequences of CAPA receptor have been deduced in silico from genomes of Bombyx mori, Apis mellifera, Nasonia vitripennis, Papilio xuthus, Tribolium castaneum, Zootermopsis nevadensis, R. microplus, Ixodes scapularis, Tetranychus urticae, and Latrodectus hesperus (14, 16–23). It has been reported that the CAPA peptide-induced Malpighian tubule fluid secretion and muscle contraction are mediated by an increase of intracellular Ca2+ via inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-induced Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum and nifedipine- and verapamil-sensitive L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (24–27). CAP2b has been shown to increase intracellular cGMP but not cAMP in tubules in D. melanogaster (28, 29); A. aegypti, A. gambiae, and G. morsitans (6); and R. prolixus (7). However, detailed information on the downstream signaling remains to be elucidated.

In the silkworm B. mori, two splice variants of the capability (capa) gene, capa-a and capa-b, have been identified in silico. The capa-a variant encodes CAPA-PVK-1, CAPA-PVK-2, and CAPA-PK, whereas capa-b encodes identical CAPA-PVK-1 and -2 and a C-terminally extended form of CAPA-PK, showing many characteristics similar to those of the Manduca and Drosophila capa genes (30). Peptidomic analysis has shown that CAPA-PVK-1 has been detected in silkworm larvae and moths, whereas CAPA-PVK-2 has been found in silkworm eggs and larvae (31). Two orphan receptor genes, BNGR-A25 and -A27, have been identified in silico as putative CAPA-PVK receptors in the Bombyx genome (17, 32). However, there are still no biochemical and pharmacological data to confirm the bioinformatics analysis results. The CAPA signaling is considered as important in the regulation of a wide range of physiological processes. Pairing of orphan receptors with the endogenous peptides is an important step to fully understand the neuropeptide-mediated downstream signaling cascades. In addition, the silkworm is an economically important insect, being a primary producer of silk, and meanwhile, as a model of Lepidoptera, the silkworm could serve as a good system for investigation of signaling and physiological functions of the CAPA peptide/receptor system. Thus, identification of the cognate receptors for Bombyx CAPA-PVKs by using a reverse physiological approach will pave the way to elucidate the possible roles in the regulation of insect fluid homeostasis, cardioacceleratory effect, developmental processes, feeding, mating, and behavior (4, 33–35).

In the present study, we have cloned the cDNAs encoding the putative CAPA peptide receptors, BNGR-A27 and two splice variants of BNGR-A25, from the brain of the silkworm B. mori and heterogeneously expressed them in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells and Spodoptera frugiperda 21 (Sf21) cells. Further functional and pharmacological characterization clarified the signaling pathways mediated by these putative CAPA-PVK receptors.

Results

Cloning and expression of the putative Bombyx CAPA receptors BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27

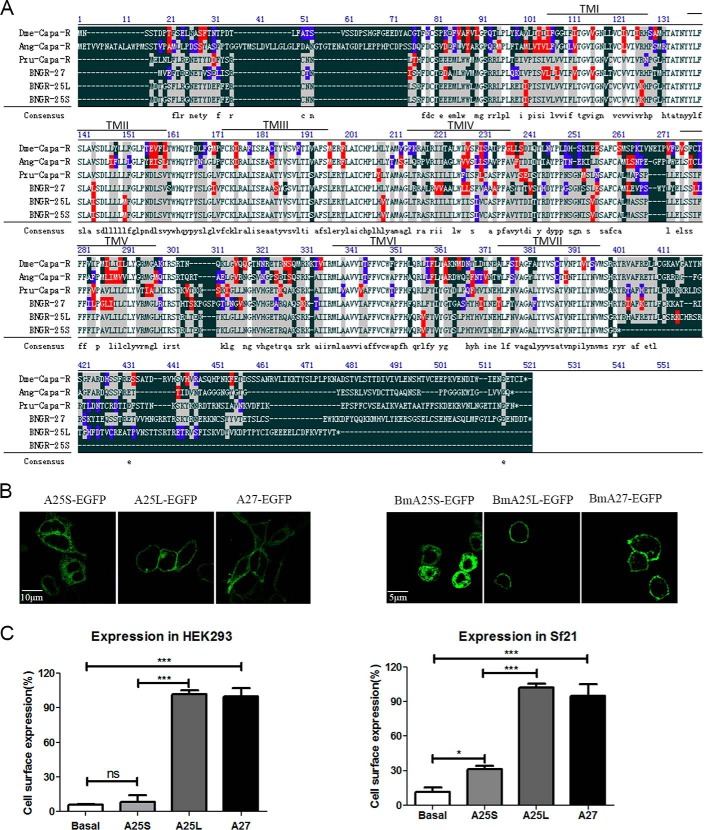

The Bombyx putative neuropeptide receptor genes BNGR-A25 and -A27 have been categorized into the same group of the CAPA-like receptors by genomic and phylogenetic analyses (17, 32). The cDNA sequences encoding the full-length BNGR-A27 (GenBankTM accession number AB330448) and two isoforms of BNGR-A25 (GenBankTM accession number AB330446 and the sequence of BNGR-A25L assembled by analysis of the RNA-seq data (SRR4425250 and SRR4425251)) were obtained by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from brain tissue of silkworm larvae. The full sequence of the predicted ORF of BNGR-A27 encodes a protein of 450 amino acids. We isolated two isoforms of BNGR-A25; the long isoform (BNGR-A25L) contains 418 amino acid residues with the intact C-terminal tail, whereas the short isoform (BNGR-A25S) consists of 341 amino acid residues with a truncated C-terminal tail. The 3′-RACE method was performed to obtain a 3′-RACE PCR fragment matching the truncated variant BNGR-A25S (supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Bioinformatics analysis of the sequences revealed that the Bombyx BNGR-A25 genomic gene is composed of seven exons and six introns, and the C-terminally truncated BNGR-A25S is generated by an intron retention event, leading to the introduction of a premature stop codon (TAA) that truncates the protein at residue 341 (supplemental Fig. S4). Protein sequence alignment between BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 and CAPA-like receptors from D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, and P. xuthus was performed (Fig. 1A). The amino acid sequence of BNGR-A25S shows 37.1, 40.3, and 66.2% identity with the D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, and P. xuthus CAPA receptors, respectively. BNGR-A25L shows 41.3, 44.1, and 72.7% identity with the D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, and P. xuthus CAPA receptors, respectively. BNGR-A27 shows 42.3, 42.4, and 58.4% identity with the D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, and P. xuthus CAPA receptors, respectively.

Figure 1.

Protein sequence alignment and expression of BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 in HEK293 and Sf21 cells. A, protein sequence alignment of BNGR-A25S (accession number AB330446), BNGR-A25L, and BNGR-A27 (accession number AB330448) with CAPA receptors from D. melanogaster (Dme-Capa-R; accession number NM_001275246); A. gambiae (Ang-Capa-R; accession number AY900217), and Papili oxuthus (Pxu-Capa-R; accession number XM_013315933). Spaces have been introduced to optimize alignment. The seven transmembranes α-helices are indicated by TM I to TM VII. The black area with white lettering indicates non-homologous residues; the white area with black lettering indicates identical residues; the gray area indicates the most frequent residues; the red area indicates strongly similar residues; and the blue area indicates weakly similar residues. B, HEK293 cells and Sf21 cells expressing BNGR-A25S-EGFP, -A25L-EGFP, and -A27-EGFP were examined by confocal microscopy. C, ELISA analysis expression of BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27. HEK293 cells and Sf21 cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged BNGR-A25S (light gray column), FLAG-tagged BNGR-A25L (dark gray column), FLAG-tagged BNGR-A27 (black column), or empty vector (white column) and subsequently detected by the M2 anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody via an ELISA assay. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from basal (control) (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Next, to verify correct expression and localization, BNGR-A25S, BNGR-A25L, and BNGR-A27 with an N-terminal FLAG or a C-terminal enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) were constructed and expressed in both human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells and Spodoptera frugiperda 21 (Sf21) cells. Western blot analysis indicated that BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 had similar total expression levels (supplemental Fig. S1A). Confocal microscopy revealed that BNGR-A25L and -A27 were predominantly expressed and localized to the cell surface with some intracellular accumulation in the absence of the ligand in both HEK293 and Sf21 cells, whereas BNGR-A25S was expressed but was predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). The ELISA analysis confirmed that both BNGR-A25L and -A27 exhibited significant cell-surface expression, whereas BNGR-A25S had almost no cell-surface expression in HEK293 cells and significantly decreased cell-surface expression in Sf21 cells compared with BNGR-A25L (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S1D). Further colocalization experiments demonstrated that extensive BNGR-A25S was observed within the endoplasmic reticulum, but obvious BNGR-A25S was retained in the Golgi compartments (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C).

BNGR-A25L and -A27 are specifically activated by Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and Bom-CAPA-PVK-2

The cyclic AMP-response element (CRE)-driven reporter gene-based functional assay was initially developed for determining the functional activity of Gs- and Gi-coupled GPCRs. However, previous studies showed that Gq-coupled receptors could induce CRE-driven reporter gene transcription through a Gq-dependent PKC/CREB cascade (36, 37). Our recent study (38) demonstrated that Gq-coupled Bombyx diapause hormone receptor is activated to induce a significant increase in CRE-driven luciferase activity in a Gq inhibitor–sensitive manner. Therefore, we employed this CRE-driven luciferase assay combined with specific inhibitors to evaluate the signaling activities of putative CAPA receptors. HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27, respectively, and pCRE-luc were established to determine the intracellular levels of cAMP. Upon stimulation with different concentrations of Bom-CAPA-PVK-1, -PVK-2, and -PK, BNGR-A25L and -A27 were activated, inducing a significant increase in luciferase activity in HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells by PVK-1 and PVK-2, whereas BNGR-A25S exhibited no response upon treatment with PVK-1, PVK-2, or PK (Fig. 2, A–C). Further investigation demonstrated that both BNGR-A25L and -A27 exhibited no response upon stimulation by other Bombyx neuropeptides, including adipokinetic hormone (AKH), corazonin, tachykinin; vice versa, Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2 failed to activate other Bombyx neuropeptide receptors, such as adipokinetic hormone receptor (AKHR), corazonin receptor, and tachykinin receptor (Fig. 2, E and F). However, a direct cAMP measurement assay by ELISA illustrated that PVK-1 and PVK-2 failed to induce significant cAMP production in HEK293-A25L or HEK293-A27 cells (Fig. 2D). These findings suggest that Gq but not Gs protein is likely to be involved in the BNGR-A25L/A27–mediated signaling (38–40).

Figure 2.

PVK-1- and PVK-2-induced expression of CRE-driven luciferase activity in BNGR-A25L/-A27– and pCRE-Luc–co-transfected HEK293 cells. A–C, dose-response curves of luciferase activities in HEK293 cells co-transfected with BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 and pCRE-Luc were determined in response to different concentrations of PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK. D, ELISA analysis of cAMP accumulation in BNGR-A25S–, BNGR-A25L–, or BNGR-A27–expressing HEK293 cells. cAMP levels in BNGR-A25S–, BNGR-A25L–, or BNGR-A27–expressing HEK293 cells were stimulated with DMEM (control), PVK-1 (1 μm), PVK-2 (1 μm), and PK (1 μm) for 15 min. E, CRE-driven luciferase activities in BNGR-A25L– or BNGR-A27– and pCRE-Luc–transfected HEK293 cells were measured in response to different B. mori neuropeptides. F, CRE-driven luciferase activities in AKHR/pCRE-Luc–, corazonin receptor (CrzR)/pCRE-Luc–, and tachykinin receptor (TKR)/pCRE-Luc–transfected HEK293 cells were measured in response to different B. mori neuropeptides. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from vehicle (control) (***, p < 0.001). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

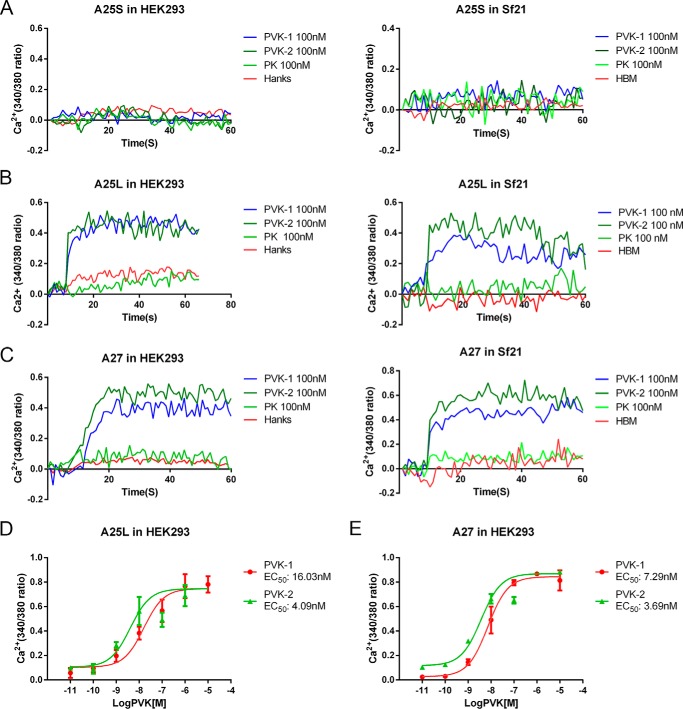

To further assess the functional activity of BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27, HEK293 cells and Sf21 cells expressing BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 were used to determine the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in response to agonists. PVK-1 and PVK-2 elicited a rapid increase of intracellular Ca2+ in a dose-dependent manner with EC50 values of 16.03 and 4.09 nm (Fig. 3, A, B, and D), respectively, in both HEK293-A25L and Sf21-A25L cells, but not in HEK293-A25S and Sf21-A25S cells. Similarly, HEK293-A27 and Sf21-A27 cells also could be stimulated by PVK-1 and PVK-2 and elicited a rapid increase of intracellular Ca2+ in a dose-dependent manner with EC50 values of 7.29 and 3.69 nm (Fig. 3, C and E), respectively. In contrast, Bom-CAPA-PK could not induce Ca2+ mobilization in both BNGR-A25L- and BNGR-A27-expressing cells. Taken together, our results suggest that BNGR-A25L and -A27 were specifically activated by Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2.

Figure 3.

PVK-1– and PVK-2–mediated induction of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in BNGR-A25L– or BNGR-A27–expressing cells. A, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293-A25S and Sf21-A25s cells were measured in response to PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK by using Fura-2/AM. B, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293-A25L and Sf21-A25L cells was measured in response to PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK by using Fura-2/AM. C, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293-A27 and Sf21-A27 cells was measured in response to PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK by using Fura-2/AM. D and E, dose-dependent curves of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells were determined in response to increasing concentrations of PVK-1 or PVK-2. All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results. Error bars, S.E.

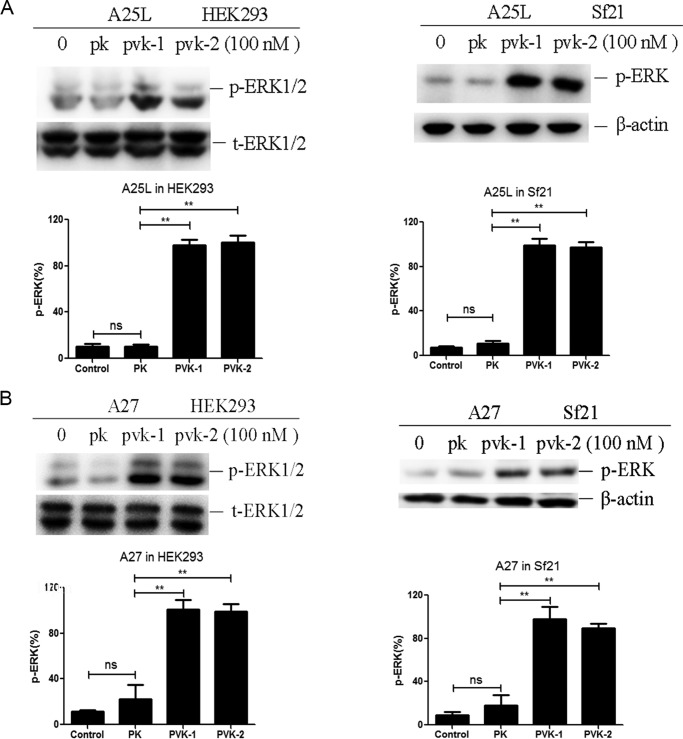

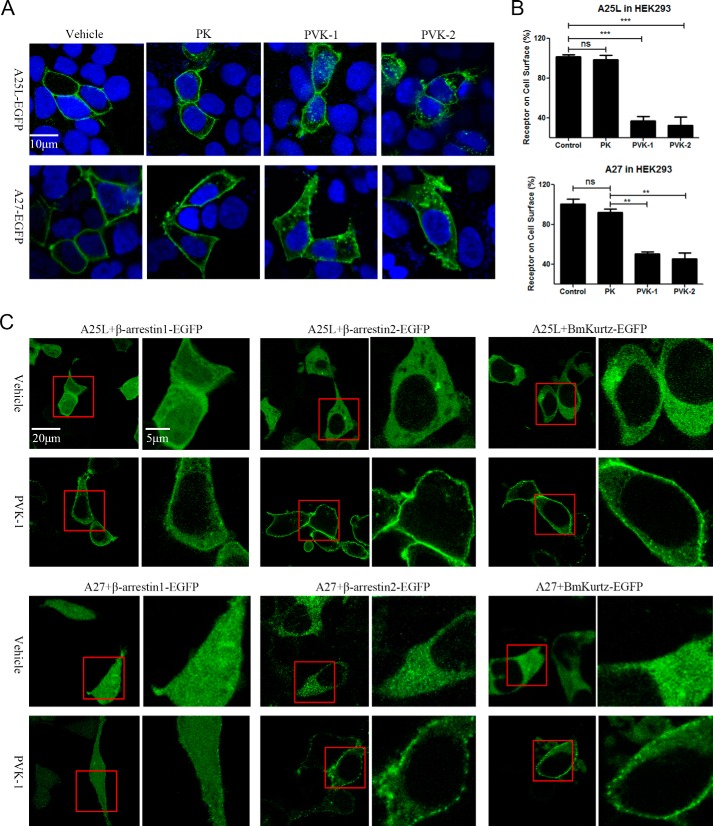

Bombyx CAPA receptors activate ERK1/2 signaling and undergo a rapid internalization upon agonist stimulation

The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 has long been used to measure the functional outcome of GPCR activation (1, 41). We therefore assessed the ERK1/2 activation by BNGR-A27. As shown in Fig. 4 (A and B), CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2 but not CAPA-PK elicited transient activation of ERK1/2 in both HEK293-A25L/Sf21-A25L cells and HEK293-A27/Sf21-A27 cells. In addition, upon agonist binding and activation, GPCRs undergo internalization from the cell surface to the cytoplasm, which is a well-characterized phenomenon (42). To visualize the internalization of BNGR-A25L and -A27, a plasmid vector to express them fused with EGFP at the C-terminal end was constructed. Observation with confocal microscopy revealed that upon activation by PVK-1 or PVK-2, BNGR-A25L and -A27 underwent a rapid and dramatic redistribution from the cell surface to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). This was also confirmed by quantitative ELISA data (Fig. 5B). Moreover, in an arrestin recruitment assay, using fusion expression of arrestins with EGFP at the C terminus, PVK-1 induced a significant translocation of β-arrestin2 and Bmkurtz, a novel nonvisual arrestin from Bombyx, from the cytoplasm into the plasma membrane, whereas only a small amount of β-arrestin1 was recruited to the plasma membrane in response to PVK-1 (Fig. 5C). Collectively, the current results suggest that both BNGR-A25L and -A27 are functional receptors specific for B. mori neuropeptides CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2. We therefore designated them as Bombyx CAPA receptors (Bom-CAPA-PVK-Rs).

Figure 4.

PVK-1– and PVK-2–induced ERK1/2 activation. A and B, PVK-1– and PVK-2–induced activation of ERK1/2. ERK1/2 phosphorylation of HEK293 cells or Sf21 cells transiently transfected with BNGR-A25L or BNGR-A27 and treated with 100 nm PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK for 5 min was assessed by Western blotting. The pERK was quantified by densitometry and expressed as a percentage of the total ERK. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from basal (control) (**, p < 0.01; ns, not significant). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Figure 5.

PVK-1 and PVK-2-mediated receptor internalization. A and B, internalization of BNGR-A25L and -A27 initiated by PVK-1 and PVK-2 in HEK293 cells. A, HEK293 cells transiently transfected with A25L-EGFP or A27-EGFP were stimulated with 100 nm PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK for 30 min and then examined by confocal microscopy. B, HEK293 cells transfected with FLAG-A25L or FLAG-A27 were stimulated with 100 nm PVK-1, PVK-2, and PK for 30 min, and the internalization of BNGR-A25L or -A27 was determined by ELISA. C, PVK-1 mediated recruitment of β-arrestin1, β-arrestin2, and BmKurtz in BNGR-A25L– or BNGR-A27–expressing HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells co-transfected with FLAG-A25L or FLAG-A27 and β-arrestin1-EGFP, β-arrestin2-EGFP, or Bombyx Kurtz-EGFP were stimulated with PVK-1 (100 nm) for 5 min and then examined by confocal microscopy. The squares in red are amplified toward the right of each corresponding image. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from basal (control) **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

BNGR-A25L and -A27 are directly activated by Bom-CAPA-PVK-1

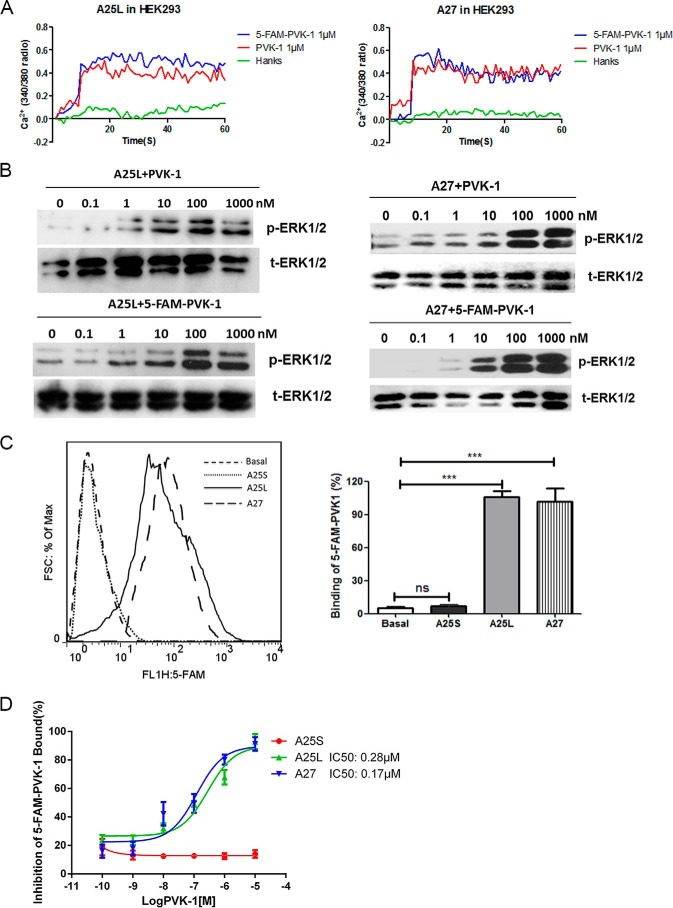

To confirm the direct interaction of BNGR-A25L and -A27 with Bom-CAPA-PVK peptides, competitive binding assays using a synthesized 5-fluorescein amide (5-FAM)–tagged PVK-1 at the N-terminal end (5-FAM–PVK-1) were performed. Functional assays showed that 5-FAM–PVK-1 could activate BNGR-A25L or -A27 in inducing intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation with an ability similar to PVK-1 (Fig. 6, A and B). To evaluate the direct interaction of CAPA-PVKs with putative CAPA receptors, putative CAPA receptor–expressing cells were incubated with 5-FAM–PVK-1 for 30–60 min and, after washing twice, analyzed by FACS. As shown in Fig. 6C, a significant increase in fluorescent intensity was detected in HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells, but not in HEK293-A25S cells, compared with untransfected HEK293 cells. In displacement competitive analysis with different concentrations of unlabeled PVK-1, 5-FAM–PVK-1 was shown to compete with unlabeled PVK-1, with IC50 values of 0.28 and 0.17 μm for BNGR-A25L and BNGR-A27, respectively (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 directly binds to and activates BNGR-A25L and -A27.

Figure 6.

Direct interactions of PVKs with BNGR-A25L and -A27. A, 5-FAM–PVK-1 activities in induction of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization were measured using HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells. B, 5-FAM–PVK-1 activities in induction of ERK phosphorylation were measured using HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells. C, binding of 1 μm 5-FAM–PVK-1 to BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 expressed in HEK293 cells was measured in the absence of unlabeled peptides by FACS. D, analyses of dose-dependent competitive binding assays. Binding of 5-FAM–PVK-1 to BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 expressed in HEK293 cells was determined in the absence or presence of different concentrations of unlabeled PVK-1. The extent of binding was determined by fluorescence intensity. Nonspecific binding was determined by detecting 1 μm 5-FAM–PVK-1 binding in the presence of 10 μm unlabeled PVK-1, whereas specific binding was calculated by subtracting nonspecific binding from the total. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from basal (unlabeled PVK-1) (***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times.

Activation of Bombyx CAPA receptor via a Gq-dependent pathway

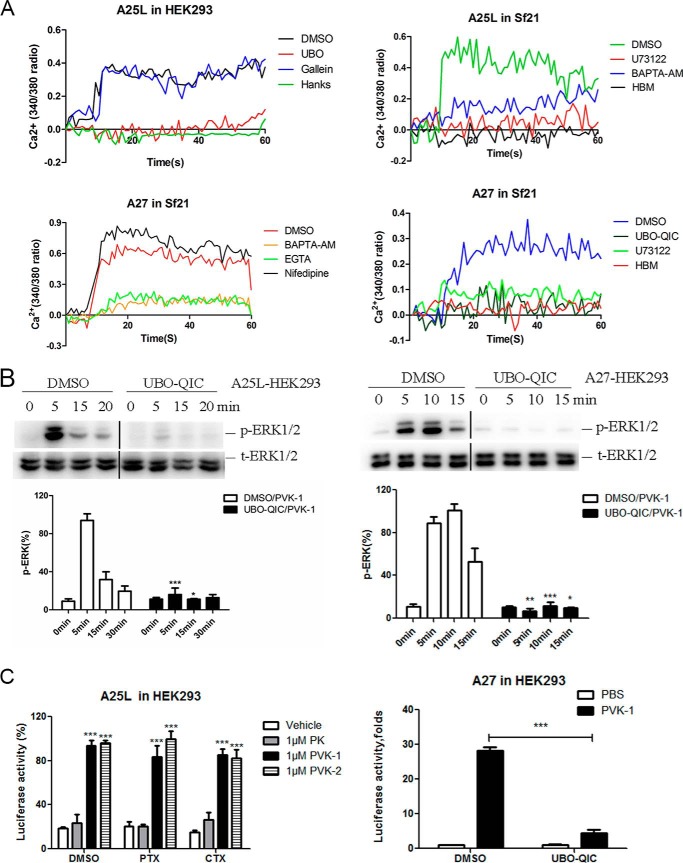

Bom-CAPA-PVK-R was activated to elicit intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in both HEK293-A25L/HEK293-A27 cells and Sf21-A25L/Sf21-A27 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Additional functional assays with specific inhibitors were performed to assess the detailed Bom-CAPA-PVK–mediated signaling pathways. Pretreatment with the Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC (43), PLC inhibitor U73122, extracellular calcium chelator EGTA, and intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM (44) led to a significant reduction in agonist-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization. By contrast, L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine and Gβγ inhibitor gallein (45) showed no effect on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization induced by PVK-1 (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC (43) and Gi inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX) were also used to characterize the signaling pathways involved in the activation of ERK1/2 or CRE-driven luciferase expression in HEK293-A25L and HEK293-A27 cells. Bombyx CAPA receptor-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and luciferase activity were significantly blocked by the Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC but could not be blocked by the Gi inhibitor PTX (Fig. 7, B and C). In addition, pretreatment with cholera toxin (CTX), an activator of Gs protein, caused a significant increase in CRE-driven luciferase activity in both vehicle- and PK-treated HEK293 cells, and stimulation with PVK-1 and PVK-2 induced further increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 7C). Taken together, the current results provide strong evidence that Bombyx CAPA receptor is specifically activated by Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2, via a Gq-dependent pathway, leading to the PLC-Ca2+-PKC signaling cascade.

Figure 7.

Activation of BNGR-A25L or -A27 via a Gq-dependent signaling cascade. A, effects of Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC (1 μm), Gβγ inhibitor gallein (10 μm), PLC inhibitor U73122 (10 μm), intracellular Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (100 μm), L-Ca2+ channel inhibitor nifedipine (10 μm), and extracellular Ca2+ chelator EGTA (10 μm) on PVK-1 (1 μm)-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in A25L-HEK293, A25L-Sf21, or A27-Sf21 cells. B, effects of Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC (1 μm) on PVK-1 (100 nm)-mediated activation of ERK1/2 in A25L-HEK293 or A27-HEK293 cells. C, effect of Gq inhibitor UBO-QIC (1 μm), Gi inhibitor PTX (100 ng/ml), and constitutive Gs agonist CTX (300 ng/ml) on PVK (1 μm)-mediated activation of CRE-driven luciferase activities in A25L-HEK293 or A27-HEK293 cells. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test revealed differences from control (DMSO) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

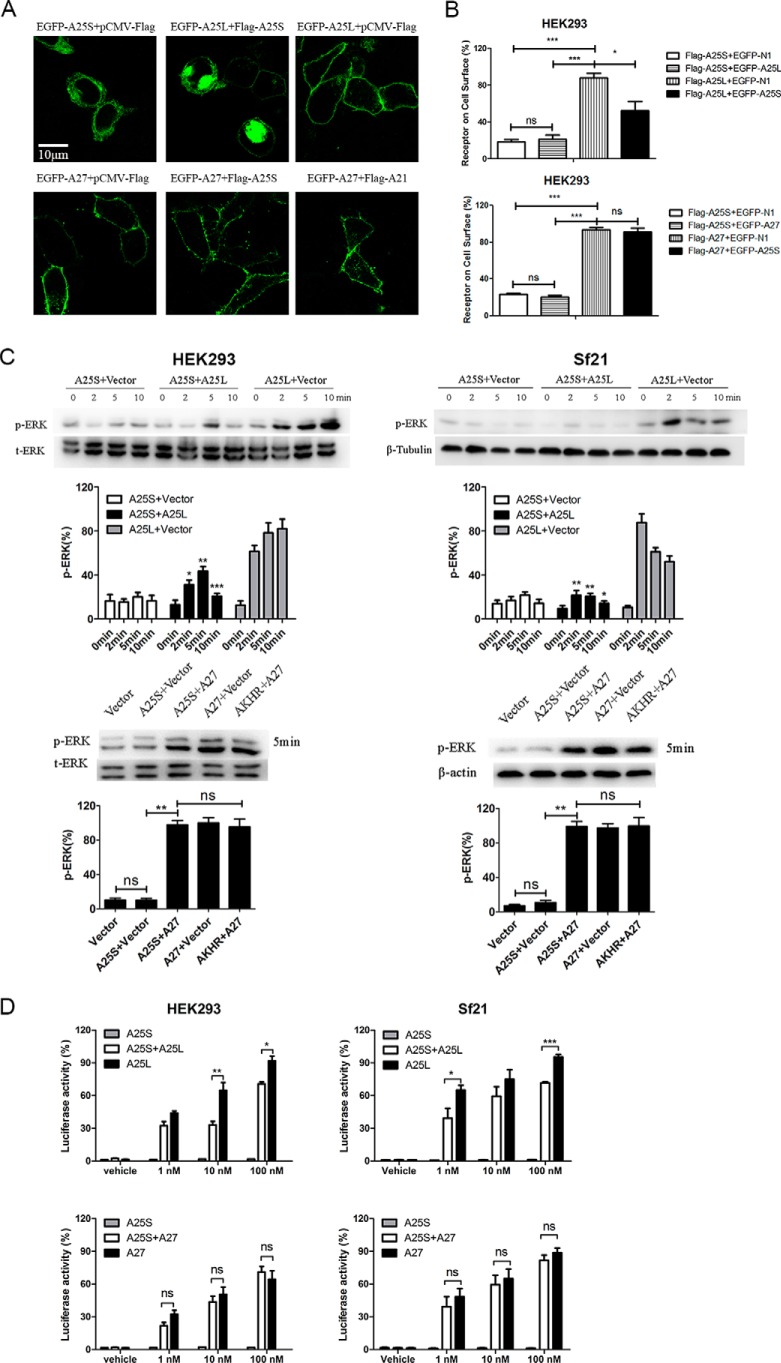

Isoform BNGR-A25S is not a functional CAPA receptor but acts as a dominant negative for BNGR-A25L

Alternative splicing–generated GPCR variants result in precisely regulated differences in expression and trafficking, ligand-binding properties, signaling pathways, and G protein–coupling efficiency (46). As shown in Figs. 1B, 2A, 3A, and 5D, when expressed alone, BNGR-A25S is certainly not a functional CAPA receptor. We therefore assess the possible effects of BNGR-A25S on expression and signaling when co-expressed with BNGR-A25L and BNGR-A27. Results derived from confocal microscopy and quantitative ELISAs showed that BNGR-A25L and -A27 are predominantly localized at the plasma membrane; in contrast, BNGR-A25S exhibits preferential retention in intracellular compartments (Fig. 1, B and C). However, co-expression of BNGR-A25S resulted in intense cytoplasmic accumulation of BNGR-A25L, but not BNGR-A27 (Fig. 8, A and B). Additionally, when co-expressed with BNGR-A25S, BNGR-A25L, but not BNGR-A27, exhibited a significant reduction in ERK phosphorylation and CRE-driven luciferase activity in response to the stimulation of Bom-CAPA-PVKs (Fig. 8, C and D). Taken together, these results suggest that BNGR-A25S is more likely to play a dominant-negative role in the regulation of the cell-surface expression and signaling of canonical BNGR-A25L.

Figure 8.

Effects of co-expression of BNGR-A25S on the cell-surface expression and functional activities of the canonical BNGR-A25L. A, confocal observation of expression of BNGR-A25L (top) and BNGR-A27 (bottom) in HEK293 cells co-transfected with or without BNGR-A25S, pCMV-FLAG, and FLAG-BNGR-A21 as controls. B, ELISA analysis of BNGR-A25L and -A27 expression in HEK293 cells co-transfected with or without BNGR-A25S. EGFP-N1 was transfected as a control. C and D, effects of co-expression of BNGR-A25S with BNGR-A25L or -A27 on PVK-mediated induction of ERK activation and CRE-driven luciferase activities. C, ERK phosphorylation of HEK293 cells or Sf21 cells transiently transfected with BNGR-A25S, BNGR-A25S and BNGR-A25L, or BNGR-A25L and treated with 100 nm PVK-1 for 5 min was assessed by Western blotting. pCMV-FLAG or AKHR was co-transfected into cells as a control vector. D, luciferase activity in HEK293 cells co-transfected with BNGR-A25S, BNGR-A25S and BNGR-A25L, or BNGR-A25L and pCRE-Luc was determined in response to different concentrations of PVK-1. Error bars, represent S.E. for three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test revealed differences from BNGR-A25L or -A27 (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Discussion

The CAPA signaling system is considered a potential target for medical importance and crop pest control. Therefore, identification of its receptors is essentially required for elucidation of the signaling mechanism(s) involved in the regulation of fluid homeostasis and even for further development of selective and environmentally friendly pest-control insecticides. Since the identification of the first CAPA receptor from D. melanogaster (9, 10), CAPA receptors have been subsequently found in representatives of the major orders, including Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera (47). CAPA receptors have also been identified in important vectors of medical and veterinary pathogens, such as different mosquito species, kissing bug, and tick (12–14, 48, 49), but not in A. aegypti (47). Genomic data mining and phylogenetic analysis suggested the presence of two paralogs of CAPA receptors in the genomes of M. sexta and the honey bee A. mellifera (16, 18). Our previous study indicated that in the B. mori genome, of 46 putative neuropeptide receptor genes, two orphan GPCR genes, BNGR-A25 and -A27, have been identified as putative CAPA peptide receptors (32). In this study, we have cloned three paralogs of putative CAPA receptors, BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27, from the silkworm B. mori. Using both HEK293 and Sf21 cells, after transfection with expression constructs, BNGR-A25L and -A27 exhibited high-level expression and correct localization on the cell surface. BNGR-A25L and -A27 were specifically activated in intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation by Bombyx CAPA-PVK-1 and CAPA-PVK-2, but not by Bombyx CAPA-PK and other neuropeptides, including Bombyx corazonin and tachykinin. Moreover, the synthetic Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 peptide N-terminally tagged with a 5-FAM–based binding assay demonstrated that Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 directly bound to BNGR-A25L and -A27. In addition, our data further showed that Bom-CAPA-PVK-R underwent a rapid internalization from the cell surface to the cytoplasm via a β-arrestin–dependent pathway following exposure to agonists. Ligand-induced receptor internalization has been recognized as a key element to regulate the strength and duration of receptor-mediated cell signaling and to directly reflect the activation of the receptor (51). Collectively, our data provide biochemical and pharmacological evidence to confirm that Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2 are the canonical ligands for BNGR-A25L and -A27. Based on phylogenetic analysis and our current results, therefore, we suggest that BNGR-A25L and -A27 are paired with neuropeptides Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2 and are better named Bom-CAPA-PVK-R1 and Bom-CAPA-PVK-R2, respectively.

Previous investigation of the myomodulatory activity of CAPA-PVKs using the cockroach hyperneural muscle bioassay showed that CAPA-PVK–induced muscle contractions were essentially dependent on the Ca2+ influx through both voltage-dependent nifedipine-sensitive and non-voltage (receptor)–operated Ca2+ channels (27). In the fruit fly, the Dme-CAPA-PVKs and Mas-CAPA-PVK-2 have been shown to activate tubule fluid secretion by increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the principal cells through both IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum and L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (24–26). In the current study, our data demonstrated that upon agonist stimulation, Bom-CAPA-PVK-R1 and -R2 evoked a rapid and transient rise of intracellular Ca2+ in a dose-dependent manner in both HEK293 and Sf21 cells (Fig. 3). Data derived from experiments with different inhibitors showed that Gq, PLC, IP3 receptor, and Ca2+ channels located on the plasma membrane are involved in Bom-CAPA-PVK-R–mediated Ca2+ mobilization. However, the Gβγ subunit and the L-type Ca2+ channel are not involved in the Bom-CAPA-PVK-R-triggered Ca2+ signaling cascade (Fig. 7A). Previous studies indicated that CAPA-PVKs activated Ca2+ influx through nifedipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane (24, 25, 52). A recent study using a genetically encoded aequorin-based luminescent Ca2+ reporter targeted to only tubule principal cells demonstrated that CAPA peptides trigger intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in a biphasic manner: a fast primary response followed by a slow secondary response (53). Taken together, our results suggest that Bom-CAPA-PVK-R1 and -R2 are Gq-coupled receptors, upon binding with agonist; Bom-CAPA-PVK-R1 and -R2 evoke intracellular Ca2+ mobilization through the IP3 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum and Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane. However, there need to be more experiments to clarify which Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane are involved in the Bom-CAPA-PVK-R–induced Ca2+ influx.

Recent studies using emerging genetic sequencing technologies have demonstrated that a single gene could generate different transcriptional isoforms because of a process known as alternative splicing, allowing the generation of several structurally and functionally distinct protein isoforms (54–56). Of 353 GPCRs detected from human airway smooth muscle, 192 GPCRs have, on average, five different expressed receptor isoforms due to splicing events (57). There are four B. mori pheromone biosynthesis–activating neuropeptide receptor variants and up to 25 alternative splicing proteins of the mouse Oprm1 gene (58). Alternative splicing also could act as a major mechanism that modulates gene expression and function of GPCRs in different species (46, 59–61). The C-terminally truncated splice variants of the μ-opioid receptor and human somatostatin receptor subtype 5 (SST5) have been found to be functionally active (62, 63). However, the majority of truncated GPCR splice variants serve as dominant-negative mutants in the regulation of the cell-surface expression and signaling of canonical receptors (64). In the current study, we identified BNGR-A25S as a splice variant with a truncated C-terminal tail generated by an intron retention event. Further investigation indicated that BNGR-A25S is not a functional receptor but is likely to act as a dominant-negative mutant for BNGR-A25S. However, additional studies are required to address the physiological roles of this splice variant BNGR-A25S in different tissues and different development stages.

In conclusion, we have paired Bom-CAPA-PVK-1 and -PVK-2 as specific canonical ligands for the Bombyx orphan receptors BNGR-A25L and -A27. Upon direct interaction with neuropeptide ligands, the Bom-CAPA-PVK receptors couple to Gq protein, triggering intracellular Ca2+ mobilization through the IP3 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum and Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane. Exposure to agonists also elicits ERK1/2 phosphorylation and receptor internalization. In addition, the Bombyx orphan receptor as a splice variant with a truncated C-terminal tail, BNGR-A25S, exhibits no functional activity when expressing alone but shows dominant-negative effects on cell-surface expression and signaling of co-expressed BNGR-A25L in response to Bom-CAPA-PVKs (Fig. 8). Our present study provides the first in-depth insights into Bom-CAPA-PVK-Rs–mediated signaling and will be helpful for further elucidation of the roles of Bom-CAPA-PVK-Rs in the regulation of fundamental physiological processes.

Experimental procedures

Materials

DMEM and FBS were purchased from Hyclone (Beijing, China). TC100 insect medium were purchased from Applichem (Darmstadt, Germany). X-tremeGENE HP was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany). G418, Lipofectamine 2000, and Opti-MEM®I reduced serum medium were purchased from Invitrogen. The pEGFP-N1 vector was purchased from Clontech. The pCMV-FLAG vector, monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, DMSO, and nifedipine were purchased from Sigma. Anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) and anti-ERK1/2 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). University of Bonn-Gq inhibitor compound (UBO-QIC) is a natural compound purified from plant (Ardisia crenata), and was purchased from Prof. Evi Kostenis (University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany). Go6983, U73122, U0126, BAPTA-AM, and gallein were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). EGTA, radioimmune precipitation lysis buffer, anti-β-actin antibody, anti-β-tubulin antibody, and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). The Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester derivative (Fura-2/AM) was purchased from Dojindo (Kyushu, Japan). The HEK293 was kindly provided by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The Sf21 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Zhifang Zhang (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Zhenjiang, China). Bom-CAPA-PVK-1, PVK-2, PK, and 5-FAM–PVK-1 were synthesized by GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the sequences are shown in supplemental Table S1.

Sequence analysis

All primers were designed using Primer Premier version 5.0 software and synthesized by Shanghai GENEray Biotechnology. cDNA and DNA segments obtained from sequencing were edited, assembled, and aligned with Editseq, Seqman, and MegAlign, respectively, in Lasergene version 7.1 software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). The transmembrane helices were predicted by TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0)6 and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/).6 The CAPA-PVK receptor sequences of other insects were accessed from GenBankTM. Splign (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/splign/splign.cgi)6 (67, 68) was used to analyze alternative splicing patterns through the Silkworm Genome Database, SilkDB (http://silkworm.genomics.org.cn/)6 (69, 70); B. mori whole-genome shotgun sequence (accession number NW_004582018.1); and Silkworm transcriptome data.

Molecular cloning and plasmid construction

Total RNA was isolated from the brain of B. mori larvae using the RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara BIO, Kusatsu, Japan), following the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Takara BIO) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To amplify the full-length sequences encoding BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27, six pairs of primers for each receptor were designed based on the sequences of GenBankTM accession numbers AB330446 and AB330448 and the sequence of BNGR-A25L assembled by analysis of the RNA-seq data (SRR4425250 and SRR4425251). As shown in Table 1 and supplemental Table S2, all primers were used in this paper. To express in insect cells, corresponding PCR products were cloned into pBmIE1-FLAG and pBmEGFP-N1, which replaced the corresponding sites of pCMV-FLAG and pEGFP-N1, as described previously (65). EGFP was fused at the C-terminal end of receptors.

Table 1.

Primers used in this work

Underlines indicate restriction enzyme cutting sites containing protective bases.

| GenBankTM accession no. | Purpose | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| AB330446 (BNGR-A25S) | Cloning into pCMV-FLAG/pBmIE1-FLAG | CCCAAGCTTGGGATGGATACTGGTTCGTTCCTTC |

| CGCGGATCCGCGTTACCTTCCACTCATTACATTG | ||

| Cloning into pEGFP-N1/pBmEGFP-N1 | CCGCTCGAGCGGATGGATACTGGTTCGTTCCTTC | |

| CCCAAGCTTGGGCCTTCCACTCATTACATTGTAC | ||

| AB330448 (BNGR-A27) | Cloning into pCMV-FLAG/ pBmIE1-FLAG | CCCAAGCTTGGGATGGTTGAATTCACACGAGAC |

| CGCGGATCCGCGTTAAGTGTCATCATTCTCCTCTC | ||

| Cloning into pEGFP-N1/pBmEGFP-N1 | CCGCTCGAGCGGATGGTTGAATTCACACGAG | |

| CCCAAGCTTGGGAGTGTCATCATTCTCCTCTC | ||

| AB330448 (BNGR-A25L) | Cloning into pCMV-FLAG/pBmIE1-FLAG | CCGGAATTCCGCCACCATGGATACTGGTTCGTTCCTTC |

| CGCGGATCCGCGTCATGTCACAGTGAAAACCTTAAAG | ||

| Cloning into pEGFP-N1/pBmEGFP-N1 | CCGGAATTCCGCCACCATGGATACTGGTTCGTTCCTTC | |

| CGCGGATCCCGTGTCACAGTGAAAACCTTAAAGT |

The corresponding PCR products of BNGR-A25S and -A27 were cloned into the sites of HindIII and BamHI of pCMV-FLAG/pBmIE1-FLAG and XhoI and HindIII of pEGFP-N1/pBmEGFP-N1. The corresponding PCR products of BNGR-A25L were cloned into the sites of EcoRI and BamHI of pCMV-FLAG/pBmIE1-FLAG/pEGFP-N1/pBmEGFP-N1, respectively. All of the targeted fragments were recombined by the Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Beyotime) and named FLAG-A25S, FLAG-A25L, and FLAG-A27; BmFLAG-A25S, BmFLAG-A25L, and BmFLAG-A27; A25S-EGFP, A25L-EGFP, and A27-EGFP; and BmA25S-EGFP, BmA25L-EGFP, and BmA27-EGFP, respectively. All of the constructs described above were sequenced by Hangzhou Tsingke Biology Co. to verify their sequences and orientations.

Cell culture and transfection

The human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (HEK293) was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 4 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. The Sf21 cell line was maintained in TC100 insect medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 28 °C. The BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 cDNA plasmid constructs were transfected into HEK293 and Sf21 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 and X-tremeGENE HP, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two days after transfection, stably expressing cells were selected by the addition of 800 mg/liter G418.

cAMP accumulation measurement

The pCRE-Luc was performed to investigate the intracellular levels of cAMP as a reporter gene system that contains the cAMP-response elements and firefly luciferase coding region as described before (65). Cells transiently or stably co-expressing BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 with pCRE-Luc were grown to 90–95% confluence in 96-well plates and stimulated with different concentrations of Bom-CAPA-PVK-1, -PVK-2, or -PK in DMEM without FBS for 4–6 h at 37 °C. Luciferase activity was detected by a firefly luciferase assay kit (KenReal, Shanghai, China). First, each well of cells was lysed by 40 μl of lysis buffer for 15 min, and then 30 μl of the whole-cell lysate were mixed with 15 μl of detection buffer for 10 min. Finally, the CRE-luciferase activity was measured using a 96-well TopCount NXT scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The direct cAMP concentration was assessed using a commercially available cAMP detection kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Intracellular calcium measurement

The fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-2/AM was performed to detect the intracellular calcium flux, as described previously (39). Briefly, the stably or transiently expressing BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 HEK293 and Sf21 cells were washed twice with PBS and suspended at 5 × 106 cells/ml in Hanks' balanced salt solution for HEK293 cells or Hepes-buffered medium for Sf21 cells. The cells were then loaded with 3 μm Fura-2/AM for 30 min. Cells were washed twice in Hanks' solution or Hepes-buffered medium. Then cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of Bom-CAPA-PVK-1, -PVK-2, and -PK. Finally, intracellular calcium flux was measured for 60 s by the ratio of excitation wavelengths at 340 and 380 nm in a fluorescence spectrometer (Infinite 200 PRO, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). All experiments of measuring Ca2+ mobilization were repeated independently at least 3–5 times.

Measurement of cell-surface receptor

ELISA was performed for quantification of receptors on the cell surface as described before (66). First, cells were transfected with various target GPCRs. 48 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with or without corresponding ligands for the indicated time. Next, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and blocked for 60 min with 1% bovine serum albumin in TBS (20 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.5). Then the cells were incubated for 2 h with a 1:2000 dilution of the mouse anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) and washed three times with TBS followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:2000 in 1% BSA/TBS) for 60 min. 150 μl of HRP substrate (Sigma) were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 20–30 min. The reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl 1% SDS, and the samples were measured at 405 nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader.

Ligand competition binding assay

Flow cytometer analysis was used to detect the binding ability of PVK-1 with BNGR-A25S, -A25L, and -A27 as described previously (50). HEK293 cells stably or transiently expressing FLAG-A25S, FLAG-A25L, or FLAG-A27 were washed with PBS containing 0.2% BSA (FACS buffer). We designed and synthesized N-terminal 5-FAM green-labeled Bom-PVK-1 peptides (supplemental Fig. S5). 5-FAM–PVK-1 and PVK-1 were diluted into FACS buffer to different concentrations and then added to the cells incubated on ice for 60–90 min. The cells were washed three times in FACS buffer and suspended in FACS buffer with 1% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. The binding ability of PVK-1 with BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of 5-FAM and presented as a percentage of total binding.

Localization and translocation assay by confocal microscopy

For the expression and translocation analysis of receptor, HEK293 cells and Sf21 cells transiently or stably expressing BNGRs-EGFP were seeded into glass coverslip 6-well plates (39). After treatment with various ligands for the indicated time or concentration, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were mounted in 50% glycerol and visualized by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss LSM510 laser-scanning confocal microscope attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and linked to a LSM5 computer system. Excitation was performed at 488 nm, and the fluorescence detection used a 505–530-nm bandpass filter.

Immunoblot analysis

To examine the phosphorylated form of ERK, HEK293 cells or Sf21 cells expressing BNGR-A25S, -A25L, or -A27 were incubated for the indicated times with different concentrations of Bom-CAPA-PVK-1, -PVK-2, and -PK. Subsequently, the cells were lysed by lysis buffer (Beyotime) containing protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) at 4 °C for 30 min on a rocker and then scraped. Afterward, proteins were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and then probed with rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody (1:2000) (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by detection using HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Beyotime). The membranes were stripped and reprobed using a polyclonal anti-β-actin/anti-β-tubulin (1:5000) (Beyotime) or anti-ERK1/2 antibody (1:2000) (Cell Signaling Technology) as a control for protein loading. Immunoreactive bands were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Cell Signaling Technology), and the membranes were then scanned using a Tanon 5200 chemiluminescent imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The intensities of bands were quantified by the Bio-Rad Quantity One imaging system.

Author contributions

N. Z. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. Y. S., L. S., and F. H. conceived the study. Z. S., Y. C., and L. H. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments. Z. S. contributed to the preparation of the figures and manuscript. Z. C. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in supplemental Fig. S2. H. Y., X. H., and Y. S. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in supplemental Figs. S2 and S3. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Q. Xia (State Key Laboratory of Silkworm Genome Biology, Southwest University, China) and F. Li (Institute of Insect Sciences, Zhejiang University, China) for considerable assistance in analyzing two sequence read archives from NCBI (i.e. SRR4425250 and SRR4425251).

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grant 2012CB910402 and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31272375, 31572462, and 31072090. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S3.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- CAP2b

- cardioacceleratory peptide 2b

- GPCR

- G protein–coupled receptor

- CRE

- cAMP-response element

- PVK

- periviscerokinin

- PK

- pyrokinin

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- CTX

- cholera toxin

- PTX

- pertussis toxin

- AKH

- adipokinetic hormone

- AKHR

- adipokinetic hormone receptor

- PBAN

- pheromone biosynthesis–activating neuropeptide

- IP3

- inositol trisphosphate

- HEK293

- human embryonic kidney 293

- Sf21

- Spodoptera frugiperda 21

- 5-FAM

- 5-fluorescein amide

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- BAPTA-AM

- 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester

- UBO-QIC

- University of Bonn-Gq inhibitor compound.

References

- 1. Masler E. P., Kelly T. J., and Menn J. J. (1993) Insect neuropeptides: discovery and application in insect management. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 22, 87–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang H., Wei Z., Nachman R. J., Adams M. E., and Park Y. (2014) Functional phylogenetics reveals contributions of pleiotropic peptide action to ligand-receptor coevolution. Sci. Rep. 4, 6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Predel R., and Wegener C. (2006) Biology of the CAPA peptides in insects. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 63, 2477–2490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huesmann G. R., Cheung C. C., Loi P. K., Lee T. D., Swiderek K. M., and Tublitz N. J. (1995) Amino acid sequence of CAP 2b, an insect cardioacceleratory peptide from the tobacco hawkmoth Manduca sexta. FEBS Lett. 371, 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tublitz N. J., and Truman J. W. (1985) Identification of neurones containing cardioacceleratory peptides (CAPs) in the ventral nerve cord of the tobacco hawkmoth, Manduca sexta. J. Exp. Biol. 116, 395–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pollock V. P., McGettigan J., Cabrero P., Maudlin I. M., Dow J. A., and Davies S. A. (2004) Conservation of capa peptide-induced nitric oxide signalling in Diptera. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 4135–4145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paluzzi J. P., and Orchard I. (2006) Distribution, activity and evidence for the release of an anti-diuretic peptide in the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 907–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hewes R. S., and Taghert P. H. (2001) Neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 11, 1126–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park Y., Kim Y. J., and Adams M. E. (2002) Identification of G protein-coupled receptors for Drosophila PRXamide peptides, CCAP, corazonin, and AKH supports a theory of ligand-receptor coevolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11423–11428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iversen A., Cazzamali G., Williamson M., Hauser F., and Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. P. (2002) Molecular cloning and functional expression of a Drosophila receptor for the neuropeptides capa-1 and -2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 299, 628–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosenkilde C., Cazzamali G., Williamson M., Hauser F., Søndergaard L., DeLotto R., and Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. (2003) Molecular cloning, functional expression, and gene silencing of two Drosophila receptors for the Drosophila neuropeptide pyrokinin-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 309, 485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olsen S. S., Cazzamali G., Williamson M., Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. P., and Hauser F. (2007) Identification of one capa and two pyrokinin receptors from the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paluzzi J. P., Park Y., Nachman R. J., and Orchard I. (2010) expression analysis, and functional characterization of the first antidiuretic hormone receptor in insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10290–10295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Y., Bajracharya P., Castillo P., Nachman R. J., and Pietrantonio P. V. (2013) Molecular and functional characterization of the first tick CAP2b (periviscerokinin) receptor from Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 194, 142–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang Y., Nachman R. J., and Pietrantonio P. V. (2015) Molecular and pharmacological characterization of the Chelicerata pyrokinin receptor from the southern cattle tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 60, 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hauser F., Cazzamali G., Williamson M., Blenau W., and Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. (2006) A review of neurohormone GPCRs present in the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster and the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Prog. Neurobiol. 80, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamanaka N., Yamamoto S., Zitnan D., Watanabe K., Kawada T., Satake H., Kaneko Y., Hiruma K., Tanaka Y., Shinoda T., and Kataoka H. (2008) Neuropeptide receptor transcriptome reveals unidentified neuroendocrine pathways. PLoS One 3, e3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hauser F., Neupert S., Williamson M., Predel R., Tanaka Y., and Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. (2010) Genomics and peptidomics of neuropeptides and protein hormones present in the parasitic wasp Nasonia vitripennis II. J. Proteome Res. 9, 5296–5310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hauser F., Cazzamali G., Williamson M., Park Y., Li B., Tanaka Y., Predel R., Neupert S., Schachtner J., Verleyen P., and Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. (2008) A genome-wide inventory of neurohormone GPCRs in the red flour beetle. Tribolium castaneum. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 29, 142–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veenstra J. A. (2014) The contribution of the genomes of a termite and a locust to our understanding of insect neuropeptides and neurohormones. Front. Physiol. 5, 454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gondalia K., Qudrat A., Bruno B., Fleites Medina J., and Paluzzi J. V. (2016) Identification and functional characterization of a pyrokinin neuropeptide receptor in the Lyme disease vector, Ixodes scapularis. Peptides 86, 42–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Veenstra J. A., Rombauts S., and Grbić M. (2012) In silico cloning of genes encoding neuropeptides, neurohormones and their putative G-protein coupled receptors in a spider mite. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 277–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Christie A. E., and Chi M. (2015) Neuropeptide discovery in the Araneae (Arthropoda, Chelicerata, Arachnida): elucidation of true spider peptidomes using that of the Western black widow as a reference. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 213, 90–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosay P., Davies S. A., Yu Y., Sözen M. A., Kaiser K., and Dow J. A. (1997) Cell-type specific calcium signalling in a Drosophila epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 110, 1683–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MacPherson M. R., Pollock V. P., Broderick K. E., Kean L., O'Connell F. C., Dow J. A., and Davies S. A. (2001) Model organisms: new insights into ion channel and transporter function: L-type calcium channels regulate epithelial fluid transport in Drosophila melanogaster. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C394–C407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pollock V. P., Radford J. C., Pyne S., Hasan G., Dow J. A., and Davies S. A. (2003) norpA and itpr mutants reveal roles for phospholipase C and inositol (1,4,5)-triphosphate receptor in Drosophila melanogaster renal function. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wegener C., and Nässel D. R. (2000) Peptide-induced Ca2+ movements in a tonic insect muscle: effects of proctolin and periviscerokinin-2. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 3056–3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davies S. A., Stewart E. J., Huesmann G. R., Skaer N. J., Maddrell S. H., Tublitz N. J., and Dow J. A. (1997) Neuropeptide stimulation of the nitric oxide signaling pathway in Drosophila melanogaster Malpighian tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 273, R823–R827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Donnell M. J., Dow J. A., Huesmann G. R., Tublitz N. J., and Maddrell S. H. (1996) Separate control of anion and cation transport in malpighian tubules of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 11631175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roller L., Yamanaka N., Watanabe K., Daubnerová I., Zitnan D., Kataoka H., and Tanaka Y. (2008) The unique evolution of neuropeptide genes in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu X., Ning X., Zhang Y., Chen W., Zhao Z., and Zhang Q. (2012) Peptidomic analysis of the brain and corpora cardiaca-corpora allata complex in the Bombyx mori. Int. J. Pept. 2012, 640359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan Y., Sun P., Wang Y., He X., Deng X., Chen X., Zhang G., Chen X., and Zhou N. (2010) The G protein-coupled receptors in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schooley D. A., Horodyski F. M., and Coast G. M. (2012) Hormones controlling homeostasis in insects. In Insect Endocrinology (Gilbert L. I., ed) pp. 366–429, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altstein M., Hariton A., and Nachman R. J. (2013) FXPRLamide (pyrokinin/PBAN) family. In Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides, 2nd Ed (Kastin A. J., ed) pp. 255–266, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fan Y., Pereira R. M., Kilic E., Casella G., and Keyhani N. O. (2012) Pyrokinin β-neuropeptide affects necrophoretic behavior in fire ants (S. invicta), and expression of β-NP in a mycoinsecticide increases its virulence. PLoS One 7, e26924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen W., Shields T. S., Stork P. J., and Cone R. D. (1995) A colorimetric assay for measuring activation of Gs- and Gq-coupled signaling pathways. Anal. Biochem. 226, 349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Durocher Y., Perret S., Thibaudeau E., Gaumond M. H., Kamen A., Stocco R., and Abramovitz M. (2000) A reporter gene assay for high-throughput screening of G-protein-coupled receptors stably or transiently expressed in HEK293 EBNA cells grown in suspension culture. Anal. Biochem. 284, 316–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jiang X., Yang J., Shen Z., Chen Y., Shi L., and Zhou N. (2016) Agonist-mediated activation of Bombyx mori diapause hormone receptor signals to extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 through Gq-PLC-PKC-dependent cascade. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75, 78–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li G., Shi Y., Huang H., Zhang Y., Wu K., Luo J., Sun Y., Lu J., Benovic J. L., and Zhou N. (2010) Internalization of the human nicotinic acid receptor GPR109A is regulated by Gi, GRK2, and Arrestin3. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22605–22618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang J., Huang H., Yang H., He X, Jiang X., Shi Y., Alatangaole D., Shi L., and Zhou N. (2013) Specific activation of the G protein-coupled receptor BNGR-A21 by the neuropeptide corazonin from the silkworm, Bombyx mori, dually couples to the Gq and Gs signaling cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 11662–11675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumari P., Srivastava A., Banerjee R., Ghosh E., Gupta P., Ranjan R., Chen X., Gupta B., Gupta C., Jaiman D., and Shukla A. K. (2016) Functional competence of a partially engaged GPCR-β-arrestin complex. Nat. Commun. 7, 13416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shenoy S. K., and Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) Multifaceted roles of β-arrestins in the regulation of seven-membrane-spanning receptor trafficking and signalling. Biochem. J. 375, 503–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jacobsen S. E., Nørskov-Lauritsen L., Thomsen A. R., Smajilovic S., Wellendorph P., Larsson N. H., Lehmann A., Bhatia V. K., and Bräuner-Osborne H. (2013) Delineation of the GPRC6A receptor signaling pathways using a mammalian cell line stably expressing the receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 347, 298–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Deng X., Yang H., He X., Liao Y., Zheng C., Zhou Q., Zhu C., Zhang G., Gao J., and Zhou N. (2014) Activation of Bombyx neuropeptide G protein-coupled receptor A4 via a Gαi-dependent signaling pathway by direct interaction with neuropeptide F from silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45, 77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Casey L. M., Pistner A. R., Belmonte S. L., Migdalovich D., Stolpnik O., Nwakanma F. E., Vorobiof G., Dunaevsky O., Matavel A., Lopes C. M., Smrcka A. V., and Blaxall B. C. (2010) Small molecule disruption of Gβγ signaling inhibits the progression of heart failure. Circ. Res. 107, 532–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oladosu F. A., Maixner W., and Nackley A. G. (2015) Alternative splicing of G protein-coupled receptors: relevance to pain management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 90, 1135–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caers J., Verlinden H., Zels S., Vandersmissen H. P., Vuerinckx K., and Schoofs L. (2012) More than two decades of research on insect neuropeptide GPCRs: an overview. Front. Endocrinol. 3, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Paluzzi J. P., and Orchard I. (2010) A second gene encodes the anti-diuretic hormone in the insect, Rhodnius prolixus. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 317, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paluzzi J. P., Russell W. K., Nachman R. J., and Orchard I. (2008) Isolation, cloning, and expression mapping of a gene encoding an antidiuretic hormone and other CAPA-related peptides in the disease vector, Rhodnius prolixus. Endocrinology 149, 4638–4646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cvejic S., Zhu Z., Felice S. J., Berman Y., and Huang X. Y. (2004) The endogenous ligand Stunted of the GPCR Methuselah extends lifespan in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moore C. A., Milano S. K., and Benovic J. L. (2007) Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 451–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kean L., Cazenave W., Costes L., Broderick K. E., Graham S., Pollock V. P., Davies S. A., Veenstra J. A., and Dow J. A. (2002) Two nitridergic peptides are encoded by the gene capability in Drosophila melanogaster. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 282, R1297–R1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Terhzaz S., Cabrero P., Robben J. H., Radford J. C., Hudson B. D., Milligan G., Dow J. A., and Davies S. (2012) Mechanism and function of Drosophila capa GPCR: a desiccation stress-responsive receptor with functional homology to human neuromedinU receptor. PLoS One 7, e29897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pan Q., Shai O., Lee L. J., Frey B. J., and Blencowe B. J. (2008) Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 40, 1413–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodley L., and Valcárcel J. (2002) Regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 1, 266–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fedor M. J. (2008) Alternative splicing minireview series: combinatorial control facilitates splicing regulation of gene expression and enhances genome diversity. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1209–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Einstein R., Jordan H., Zhou W., Brenner M., Moses E. G., and Liggett S. B. (2008) Alternative splicing of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily in human airway smooth muscle diversifies the complement of receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5230–5235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee J. M., Hull J. J., Kawai T., Goto C., Kurihara M., Tanokura M., Nagata K., Nagasawa H., and Matsumoto S. (2012) Re-evaluation of the PBAN receptor molecule: characterization of PBANR variants expressed in the pheromone glands of moths. Front. Endocrinol. 3, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee H. J., Wall B., and Chen S. (2008) G-protein-coupled receptors and melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 21, 415–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Majumdar S., Grinnell S., Le Rouzic V., Burgman M., Polikar L., Ansonoff M., Pintar J., Pan Y. X., and Pasternak G. W. (2011) Truncated G protein-coupled μ opioid receptor MOR-1 splice variants are targets for highly potent opioid analgesics lacking side effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19778–19783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Markovic D., and Challiss R. A. (2009) Alternative splicing of G protein-coupled receptors: physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 66, 3337–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Córdoba-Chacón J., Gahete M. D., Duranprado M., Pozo-Salas A. I., Malagón M. M., Gracia-Navarro F., Kineman R. D., Luque R. M., and Castaño J. P. (2010) Identification and characterization of new functional truncated variants of somatostatin receptor subtype 5 in rodents. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 67, 1147–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lu Z., Xu J., Rossi G. C., Majumdar S., Pasternak G. W., and Pan Y. X. (2015) Mediation of opioid analgesia by a truncated 6-transmembrane GPCR. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 2626–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McManus S., and Roux S. (2012) The roles played by highly truncated splice variants of G protein-coupled receptors. J. Mol. Signal. 7, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang H., He X., Yang J., Deng X., Liao Y., Zhang Z., Zhu C., Shi Y., and Zhou N. (2013) Activation of cAMP-response element-binding protein is positively regulated by PKA and calcium-sensitive calcineurin and negatively by PKC in insect. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 1028–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang H., He X., Deng X., Li G., Ying G., Sun Y., Shi L., Benovic J. L., and Zhou N. (2010) Bombyx adipokinetic hormone receptor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 via G protein-dependent PKA and PKC but β-arrestin-independent pathways. Biochemistry 49, 10862–10872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kapustin Y., Souvorov A., Tatusova T., and Lipman D. (2008) Splign: algorithms for computing spliced alignments with identification of paralogs. Biol. Direct 3, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kapustin Y., Souvorov A., and Tatusova T. (2004) Splign - a hybrid approach to spliced alignments. Abstracts of the Eighth Annual International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology (RECOMB 2004): Currents in Computational Molecular Biology. Abstr. K11, p. 741 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Biology Analysis Group (2004) A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 306, 1937–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wang J., Xia Q., He X., Dai M., Ruan J., Chen J., Yu G., Yuan H., Hu Y., Li R., Feng T., Ye C., Lu C., Wang J., Li S., et al. (2005) SilkDB: a knowledgebase for silkworm biology and genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D399–D402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.