Abstract

The function of protein products generated from intramembraneous cleavage by the γ-secretase complex is not well defined. The γ-secretase complex is responsible for the cleavage of several transmembrane proteins, most notably the amyloid precursor protein that results in Aβ, a transmembrane (TM) peptide. Another protein that undergoes very similar γ-secretase cleavage is the p75 neurotrophin receptor. However, the fate of the cleaved p75 TM domain is unknown. p75 neurotrophin receptor is highly expressed during early neuronal development and regulates survival and process formation of neurons. Here, we report that the p75 TM can stimulate the phosphorylation of TrkB (tyrosine kinase receptor B). In vitro phosphorylation experiments indicated that a peptide representing p75 TM increases TrkB phosphorylation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Moreover, mutagenesis analyses revealed that a valine residue at position 264 in the rat p75 neurotrophin receptor is necessary for the ability of p75 TM to induce TrkB phosphorylation. Because this residue is just before the γ-secretase cleavage site, we then investigated whether the p75(αγ) peptide, which is a product of both α- and γ-cleavage events, could also induce TrkB phosphorylation. Experiments using TM domains from other receptors, EGFR and FGFR1, failed to stimulate TrkB phosphorylation. Co-immunoprecipitation and biochemical fractionation data suggested that p75 TM stimulates TrkB phosphorylation at the cell membrane. Altogether, our results suggest that TrkB activation by p75(αγ) peptide may be enhanced in situations where the levels of the p75 receptor are increased, such as during brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and epilepsy.

Keywords: autophosphorylation, intramembrane proteolysis, p75 neurotrophin receptor, receptor tyrosine kinase, transmembrane domain

Introduction

Intramembranous cleavage is mediated by γ-secretase, a multisubunit complex consisting of presenilin 1 or 2, nicastrin, anterior pharynx defective 1, and presenilin enhancer 2 (1). The p75 neurotrophin receptor undergoes sequential proteolytic cleavage first by metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17), which generates an ectodomain (ECD)2 and a carboxyl-terminal fragment (CTF) (2) similar to amyloid precursor protein (APP) and Notch-1. p75CTF is subsequently cleaved by γ-secretase and produces an intracellular domain, p75ICD, and a transmembrane domain, p75(αγ), that is predominately hydrophobic (3).

p75 is a type 1 membrane protein that is expressed in many neuronal cell types including stem cells, astrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursors, Schwann cells, and olfactory unsheathing glia. p75 is expressed during early development in many neural crest derivatives, such as sympathetic, sensory, enteric neurons, and Schwann cells (4). Significantly, later in development and in the adult, p75 expression is robustly up-regulated following injury, inflammation, or axotomy (5). The p75 receptor shares many common features with the tumor necrosis family of receptors, including extracellular cysteine repeats, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain with a death domain motif (6). Although controversial, p75 can exist as a monomer, as a dimer (7, 8), or in a trimeric form similar to other tumor necrosis family members (9).

There are many effects of p75 signaling because this receptor can bind pro- and mature neurotrophins to regulate a wide range of cellular functions, including programmed cell death, axonal growth and degeneration, cell proliferation, myelination, and synaptic plasticity through interaction with other receptors (10). For example, p75 modulates neurotrophin responsiveness through interactions with TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC (11). Moreover, p75 can modulate axonal guidance via association with the Nogo receptor and Lingo-1, as well as Ephrin A (12). The interaction between p75 and Sortilin facilitates pro NGF-induced neuronal apoptosis (13).

Studies on different regions of p75 suggested that the ECD binds to and sequesters pro-neurotrophins and other neurodegenerative ligands, thereby preventing neuronal death (14). The p75ICD has been found to exert an effect upon nuclear events and induce apoptosis through the transcription factor NFκB (15). Other in vitro experiments suggested that p75ICD can influence gene transcription events in the nucleus (16). Although the intramembranous cleavage of APP has been associated with the development of Alzheimer's disease (17, 18), the functional consequences of the transmembrane domain of p75, a similar product of γ-secretase cleavage, is not well understood.

The insulin receptor, which belongs to the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family, also undergoes cleavage by γ-secretase (19), producing an insulin receptor transmembrane peptide that can facilitate activation of the insulin receptor (20). This suggests the transmembrane domain of a receptor may possess functions after cleavage.

The p75 TM is highly conserved across species, much more so than the ligand-binding cysteine repeats or the cytoplasmic death domains (21). This strong conservation implies that the TM domain possesses a vital function. Previous studies indicated that the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of p75 were responsible for regulating the affinity of binding of NGF to TrkA and potentiating Trk-mediated survival signaling (22). In addition, p75 was co-precipitated with Trk receptors, particularly the TrkB receptor (11). These results implied that there are interactions between p75 and Trk receptors (11, 22). Another reason for considering the cleavage of p75 is that this receptor is frequently elevated during traumatic brain injury, seizures, and several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's dementia. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether the p75 TM, as well as the p75(αγ) peptide generated by intramembraneous cleavage, can have a functional consequence, such as influencing TrkB activity.

In this study, we focused on the TrkB receptor, which is widely expressed in the CNS. In contrast, TrkA is expressed predominately in sensory and sympathetic neurons in the peripheral nervous system and restricted to basal forebrain neurons in the brain (23). The TrkB receptor has been of considerable interest because of its involvement in many neurological and psychiatric disorders (24, 25). Consequently, there has been a concerted effort to understand how the TrkB receptor is regulated. It is known that p75 and the TrkB receptor interact (11); however, the mechanism of this interaction is not completely clear. Here, we provide evidence for an unexpected mechanism whereby p75 TM may associate with TrkB and influence its activation.

Results

The transmembrane domain of p75, but not EGFR or FGFR1, enhances TrkB phosphorylation

The TrkB receptor, a member of the tyrosine kinase family of transmembrane receptors, plays a prominent role in the development and maintenance of the vertebrate nervous system. TrkB is predominantly expressed in many CNS regions, including the cerebellum, cortex, hippocampus, and the striatum. TrkB receptor signaling through intracellular tyrosine kinase phosphorylation plays a critical role in survival, plasticity, and long-term potentiation (26, 27), as well as cognitive and psychiatric functions (28). TrkB receptor signal transduction is required for neuronal differentiation, axonal growth, and synaptic transmission (29, 30). All these actions of TrkB require autophosphorylation stimulated by neurotrophin binding. In addition to BDNF, TrkB can also be activated by NT-3, by NT-4, and through transactivation of G-protein–coupled receptor ligands such as adenosine (31, 32).

The p75 receptor can directly bind to both mature and pro-forms of the neurotrophins. Several reports have indicated that p75 interactions with Trk receptors (11) enhance binding affinity of Trk to ligands when both receptors are co-expressed (33, 34). However, the nature of p75/Trk interactions is not clear. To address this question, we established an in vitro phosphorylation assay to follow the activity of TrkB using a phospho-specific antibody against Tyr816 of TrkB (35). Based upon previous findings that p75 receptors lacking the extracellular domain could influence Trk binding (22), we designed an experiment to test whether the p75 TM domain (Table 1) has any effect upon TrkB activation.

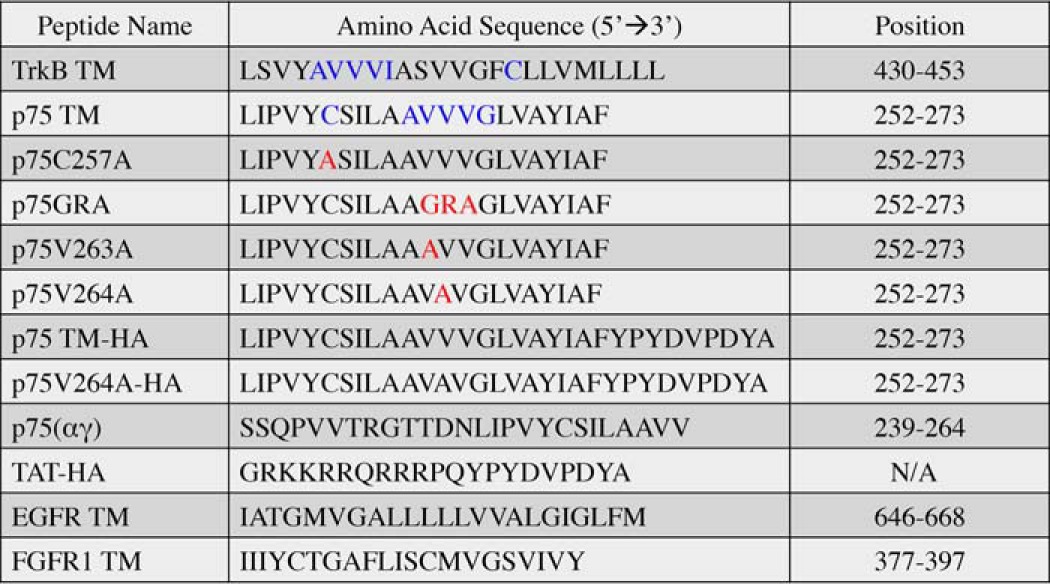

Table 1.

Amino acid sequences of the various peptides used in this study

TrkB TM and all p75 derivatives peptides were designated with the amino acid position according to the rat sequence. EGFR TM and FGFR1 TM were designated with the amino acid position according to the human sequence. Blue colored sequence “AVVVL” in TrkB TM and “AVVVG” in p75 TM represent self-associative motifs. Blue colored “C” TrkB TM and p75 TM are known to participate in disulfide binding. Red colored sequences represent the mutation sites.

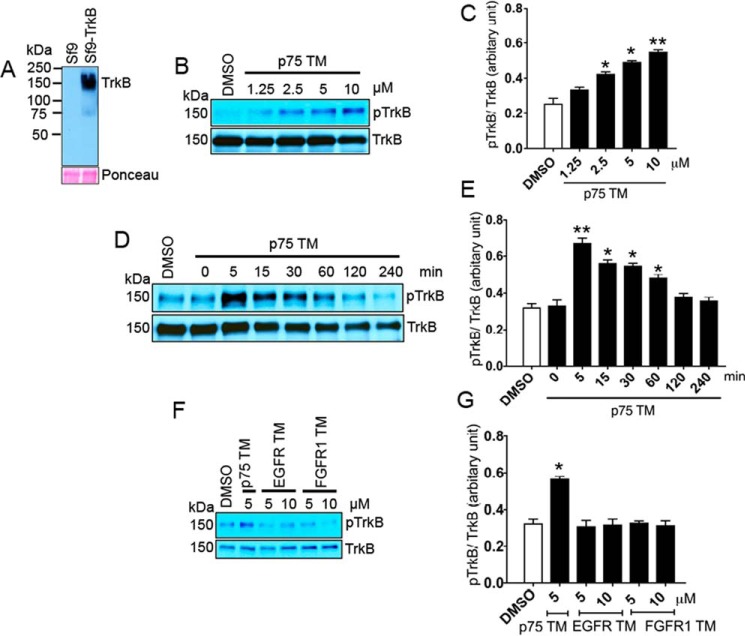

We incubated 600 ng (0.2 μm) of TrkB in 20 μg of solubilized Sf9-TrkB lysate (supplemental Fig. S1) with a peptide containing the transmembrane sequence of p75 (p75 TM). We observed increasing TrkB phosphorylation in response to increasing concentrations (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm) of p75 TM (Fig. 1, B and C). According to our stoichiometric calculation, 0.2 μm TrkB incubated with 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm p75 TM used in our study had TrkB:p75 TM ratios of 1:6.25, 1:12.5, 1:25, and 1:50, respectively.

Figure 1.

The transmembrane domain of p75 but not EGFR or FGFR1 enhances TrkB phosphorylation. A, protein expression levels of rat TrkB in Sf9 cells using the Bac-to-Bac® baculovirus expression system compared with non-transfected Sf9 cells. Ponceau staining was used as a loading control. B and C, Western blot and its corresponding quantification of an in vitro phosphorylation assay demonstrate a dose-dependent effect of p75 TM over 30 min on TrkB (Tyr816) phosphorylation. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus DMSO. D and E, Western blot and its analyses show effects of 5 μm p75 TM on TrkB phosphorylation over time. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. F and G, the effects of 5 and 10 μm EGFR and FGFR1 transmembrane domains on TrkB phosphorylation were detected by Western blot and quantified. *, p < 0.05. The ratios of 0.2 μm TrkB incubated with 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm of TM peptides were 1:6.25, 1:12.5, 1:25, and 1:50, respectively (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.).

To determine the time course of this activation, we assayed the effect of 5 μm p75 TM upon TrkB phosphorylation. The results indicated that the phosphorylation of TrkB increased dramatically within 5 min and persisted up to 60 min (Fig. 1, D and E). This time course is similar to the activation of TrkB by BDNF (36).

To test the specificity of p75 TM effects on TrkB phosphorylation, we tested the TM domain from other tyrosine kinase receptors, in particular the TM domains from FGFR1 and EGFR (Table 1). Phosphorylation assay data showed that neither EGFR TM nor FGFR1 TM could induce TrkB phosphorylation under similar conditions as incubation with p75 TM (Fig. 1, F and G). Because there is minimal homology between the TM domains of EGFR and FGFR1 with p75 TM, these results suggest that there is some specificity in the effects of p75 TM on TrkB activity.

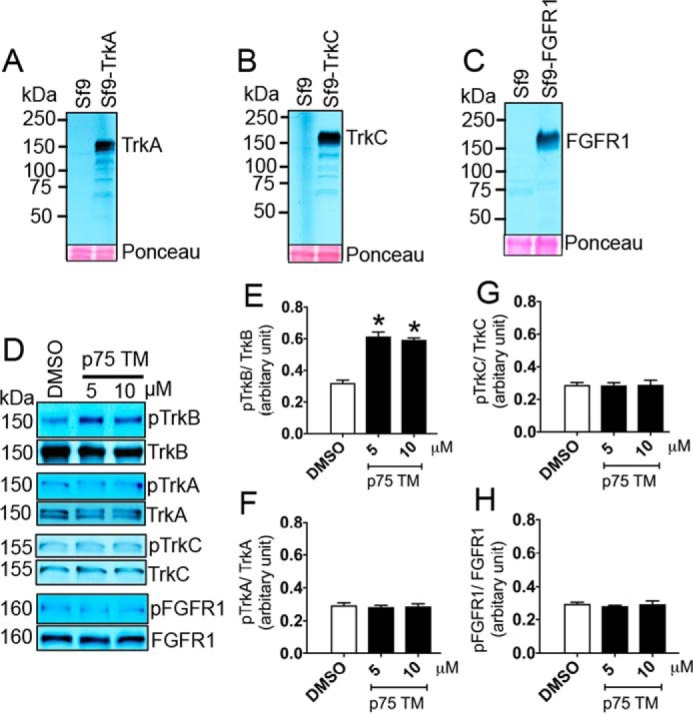

The transmembrane domain of p75 does not enhance TrkA, TrkC, or FGFR1 phosphorylation

Next, to examine whether TrkB is the only member of the RTKs that can be activated by the p75 TM, we extended our in vitro phosphorylation assay to elucidate whether 5 and 10 μm p75 TM alters TrkA (Tyr816), TrkC (Tyr820), or FGFR1 (Tyr653/Tyr654) phosphorylation under the same conditions utilized for TrkB. The data suggest that none of these receptors are activated by the p75 TM, supporting the specificity of p75 TM on TrkB phosphorylation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The transmembrane domain of p75 does not enhance TrkA, TrkC, or FGFR1 phosphorylation. A–C, protein expression of rat TrkA (A), TrkC (B), and human FGFR1 (C) in Sf9 cells using the Bac-to-Bac® baculovirus expression system compared with non-transfected Sf9 cells. Ponceau staining was used as a loading control. D, in vitro phosphorylation assay and a Western blot analysis were used to evaluate the effects of a 30-min incubation of 5 and 10 μm p75 TM on 0.2 μm TrkB (Tyr816), TrkA (Tyr816), TrkC (Tyr820), and FGFR1 (Tyr653/Tyr654) phosphorylation. E–H, a respective quantification of D (n = 3 independent experiments; means ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05 versus DMSO.

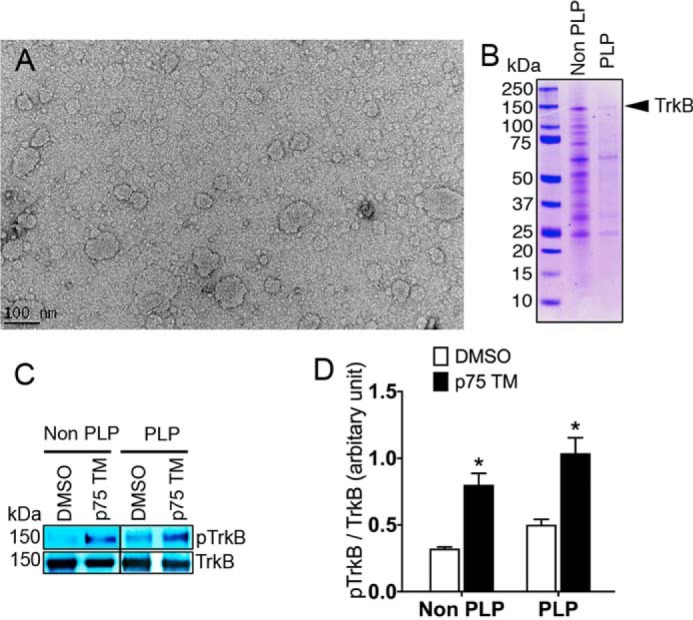

The phosphorylation of reconstituted TrkB in brain lipids (TrkB proteoliposome) is enhanced upon treatment with p75 TM

The in vitro phosphorylation experiment was conducted in the presence of detergents to solubilize the TrkB protein. To assess the effect of p75 in the absence of detergent, we established a proteoliposome system to provide a more natural environment for the phosphorylation assay. To prepare the proteoliposomes, TrkB was reconstituted in brain lipids by using Bio-Beads SM2 to remove the detergent (37). Subsequently, the effect of 5 μm p75 TM on TrkB phosphorylation over 30 min was assessed using the in vitro phosphorylation assay and Western blot. Our results demonstrate that the p75 TM peptide is capable of inducing TrkB phosphorylation in the absence of detergent (Fig. 3). This suggests that p75 TM is capable of activating TrkB in the environment of a lipid bilayer, which may occur in vivo when p75 undergoes cleavage.

Figure 3.

The phosphorylation of TrkB embedded in proteoliposomes is enhanced upon treatment with p75 TM. A, proteoliposome formation was confirmed by electron microscopy. Scale bar, 100 nm. B, Coomassie Blue (R250) staining was used to detect TrkB in solubilized Sf9 cells in non-proteoliposome (Non PLP) and proteoliposome (PLP) samples. C and D, Western blot and its quantification represent the effect of 5 μm p75 TM over 30 min on the phosphorylation of TrkB (Tyr816) in non-proteoliposome and proteoliposome samples. The TrkB:p75 TM ratio was 1:25 (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05 versus DMSO.

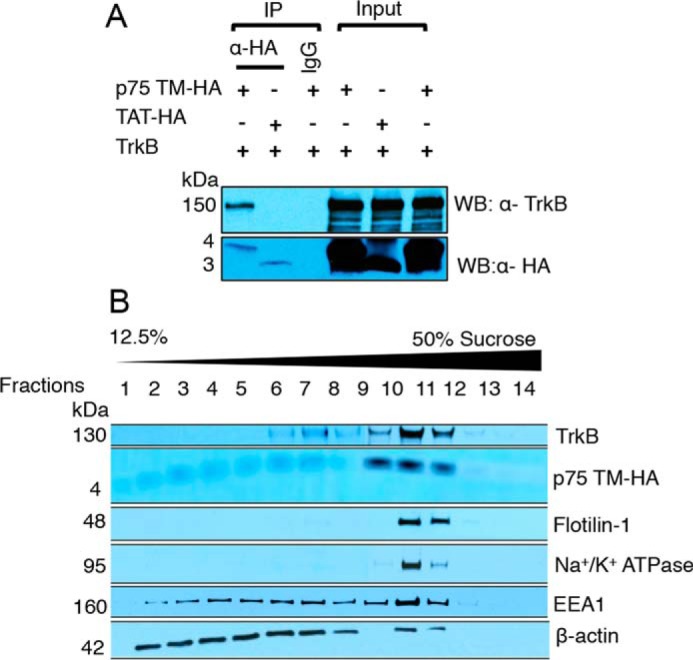

The transmembrane domain of p75 interacts with TrkB and co-localizes with TrkB in lipid raft regions of the plasma membrane in vitro

Previous studies showed that the activation of TrkB signal transduction pathways were initiated in lipid rafts (38). Furthermore, the mechanism by which the transmembrane domain of the insulin receptor triggers the activation of the insulin receptor was proposed to interact with and facilitate a dimerization of the holo-receptors at the plasma membrane (20). Therefore, we sought to examine whether there are similar interactions between p75 TM and TrkB and whether this interaction occurs at the cell membrane and lipid raft regions.

To test whether p75 TM interacts with TrkB, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay using a p75 TM peptide linked to an C′-terminal HA epitope and solubilized TrkB protein. Mouse anti-HA antibody was used to immobilize p75 TM-HA or TAT-HA. TrkB was detected by a Western blot using rabbit anti-TrkB (H-181) (Fig. 4A). The interaction between p75 TM-HA with TrkB was also confirmed by reverse co-IP using anti-rabbit polyclonal TrkB (H-181) antibody to immobilize TrkB and mouse anti-HA antibody to detect p75 TM-HA (supplemental Fig. S2). Our results demonstrated that p75 TM-HA interacted with TrkB. We then examined whether p75 TM co-localizes with TrkB using sucrose subcellular fractionation experiments. Using Flotilin-1 as a marker of lipid rafts and Na+/K+-ATPase as a cell membrane marker, we found that p75 TM was localized with TrkB in the lipid raft fractions, whereas the p75 TM and TrkB distribution was not significantly detected in cytosolic cell compartments, including early endosomes using EEA1 as a marker (Fig. 4B). This suggests that p75 TM may stimulate TrkB phosphorylation through an interaction that may take place at the cell surface.

Figure 4.

The transmembrane domain of p75 interacts with TrkB and co-localizes with TrkB in lipid raft regions of the plasma membrane in vitro. A, the interaction between p75 TM peptide and TrkB was detected in Sf9-TrkB cell lysates by co-IP. Mouse anti-HA antibody was used to immobilize p75 TM-HA or TAT-HA. TrkB was detected by Western blot using rabbit anti-TrkB (H-181). Mouse IgG was used as an IP control, and it did not pull down p75 TM-HA or TAT-HA. TAT-HA was used as a control for HA tag. B, sucrose subcellular fractionation assay was used to detect the distribution of p75 TM and the TrkB receptor. The membrane was then probed with antibodies against Flotilin-1 (lipid raft marker), Na+/K+-ATPase (cell membrane marker), EEA1 (early endosome marker), and β-actin (a cytosolic marker) (n = 3 individual experiments).

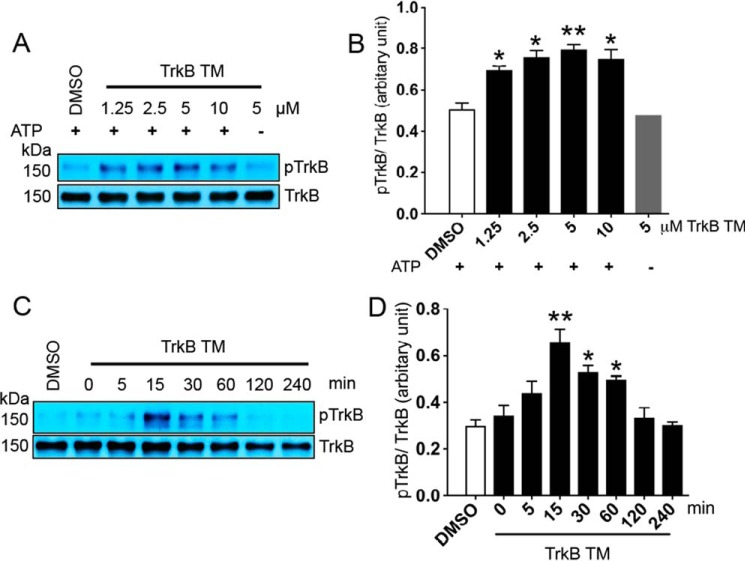

The transmembrane domain of TrkB enhances the phosphorylation of the TrkB receptor

It has been reported that the activation of the insulin receptor can be enhanced by its own transmembrane domain (20). Because TrkB and the insulin receptor both belong to the RTK family, we investigated whether TrkB TM is capable of triggering TrkB phosphorylation using our in vitro phosphorylation assay. Incubation of 0.2 μm solubilized TrkB with 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm TrkB TM (Table 1), in same ratio utilized for p75 TM dose-dependent experiments, stimulated TrkB phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner within 30 min (Fig. 5, A and B). To address the time course of the response, 5 μm TrkB TM was then incubated with TrkB over a 4-h time course. The Western blot demonstrated that the phosphorylation of TrkB could be enhanced within 15 min and persisted up to 60 min (Fig. 5, C and D). This suggests that TrkB phosphorylation can be enhanced by treatment with its own transmembrane domain. The interaction between the transmembrane domain of TrkB and the TrkB receptor may help provide insight into how p75 TM increases TrkB phosphorylation. Because p75 TM and TrkB TM both have more than four common amino acid residues implicated in their dimerization, including a cysteine and three valines in self-associative motifs (Table 1, blue), we propose that the self-associative motifs may play a role in TrkB activation (9, 39).

Figure 5.

Transmembrane domain of TrkB enhances phosphorylation of the TrkB receptor. A and B, Western blot and its corresponding analyses demonstrate a dose-dependent effect of TrkB TM over 30 min on TrkB (Tyr816) phosphorylation using an in vitro phosphorylation assay. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus DMSO. 5 μm TrkB TM treatment in the absence of ATP was utilized as an experimental control. C and D, Western blot and its statistical analyses show the time-dependent effects of 5 μm TrkB TM on TrkB phosphorylation. The ratios of 0.2 μm TrkB incubated with 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm of TrkB TM were 1:6.25, 1:12.5, 1:25, and 1:50, respectively. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus DMSO (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.).

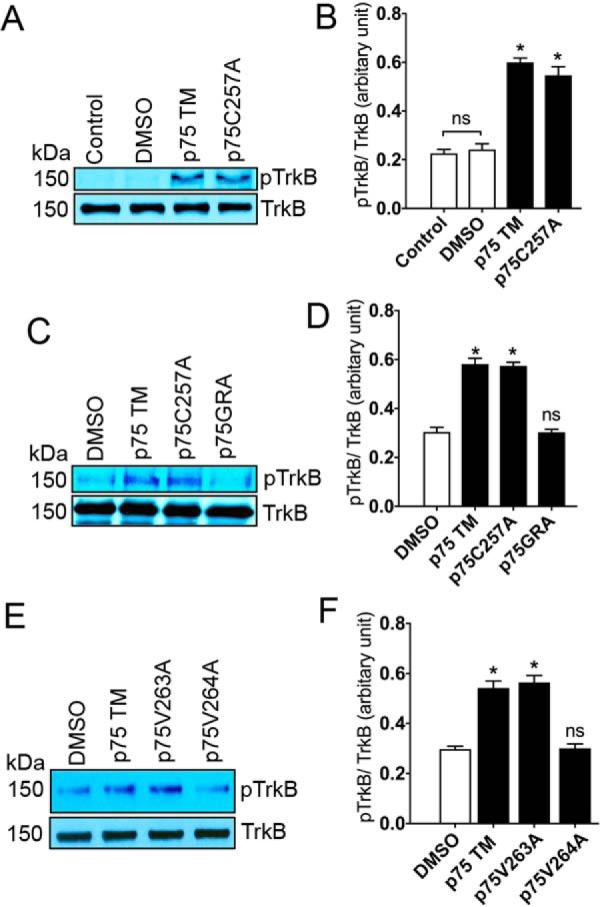

Mutagenesis analyses reveal that valine 264 is critical for p75 TM-induced TrkB phosphorylation

To characterize which regions in p75 TM are responsible for inducing TrkB phosphorylation, we tested the effects of several mutations in the transmembrane domain on stimulating TrkB activation. Each peptide is designated with the amino acid position according to the rat sequence (Table 1). A cysteine residue at position 257 in the transmembrane domain of human p75 is known to stabilize receptor dimerization through a disulfide bond and increase p75 activity (8). The cysteine residue was shown to induce constitutive p75 dimerization and activate the receptor even in the absence of NGF (40). These studies implied that the cysteine residue is crucial for p75 receptor activity. We therefore investigated whether a specific mutation of cysteine to alanine (C257A) in p75 TM influences TrkB activation. Incubation of the C257A p75 transmembrane peptide was still capable of inducing in vitro TrkB phosphorylation, suggesting that the cysteine residue may not participate in p75 TM-induced TrkB activation (Fig. 6, A and B). In addition, a series of consecutive valine residues in the transmembrane domain of p75 have been proposed to act as a self-associative motif, AVVVG (Table 1, blue) (39, 41). This hydrophobic series of amino acids overlaps with the site of cleavage by the γ-secretase complex (3). Previously, a mutation of a valine residue in this motif was reported to change the motif orientation and prevent γ-secretase cleavage of the receptor (41).

Figure 6.

Mutagenesis analyses reveal that valine 264 is critical for p75 TM-induced TrkB phosphorylation. A–F, Western blots and corresponding quantifications show the effects of 30-min incubations with 5 μm p75 TM, p75C257A, p75GRA, p75V763A, or p75V764A on TrkB phosphorylation (Tyr816) using an in vitro phosphorylation assay. The ratio of 0.2 μm TrkB incubated with 5 μm of TM peptides was 1:25 (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05 versus DMSO.

To examine whether the AVVVG motif is involved in TrkB activation, we generated a peptide with a triple mutation replacing the valines in p75 TM to GRA (Table 1). The results using the in vitro TrkB phosphorylation assay demonstrated that the triple mutation prevented the effects of p75 TM upon TrkB phosphorylation (Fig. 6, C and D). We also explored the effects of an individual mutation of valine to alanine at position 263 and 264 (Table 1), which is adjacent to the γ-secretase cleavage site, on TrkB phosphorylation. The results showed that the phosphorylation of TrkB was significantly decreased after incubation with the p75V264A peptide, whereas the p75V263A induced the same levels of TrkB phosphorylation as p75 TM (Fig. 6, E and F). Because p75V264A, unlike p75 TM, does not stimulate TrkB phosphorylation, we ran a co-IP assay to see whether p75V264A interacts with TrkB. Our results showed that p75V264A did not interact with TrkB (supplemental Fig. S2).

Because p75GRA and p75V264A mutations failed to interact and stimulate TrkB phosphorylation, we sought to understand whether or not the mutations alter secondary structure of p75. To address this issue, we utilized the SPLIT 4.0 SERVER program (http://splitbioinf.pmfst.hr/split/4/)3 (42) to predict the α-helix preference of p75 neurotrophin receptor and the effect of mutations utilized in this study. According to the α-helix predictions made by the program, GRA slightly reduced α-helix preference; however, V264A mutation did not impact α-helix preference in the p75 neurotrophin receptor, which suggests that p75V264A does not disrupt the intermembrane region (supplemental Fig. S3).

Altogether, these data suggests that a valine 264 in p75 TM has consequences upon both intramembraneous cleavage by γ-secretase (43) and activation of the TrkB receptor. Because the transmembrane domain of TrkB, like p75, induces TrkB phosphorylation and both TrkB and p75 possess a self-associative motif with shared triple valines, we hypothesize that the cluster of valines in p75 TM may be involved in triggering TrkB phosphorylation.

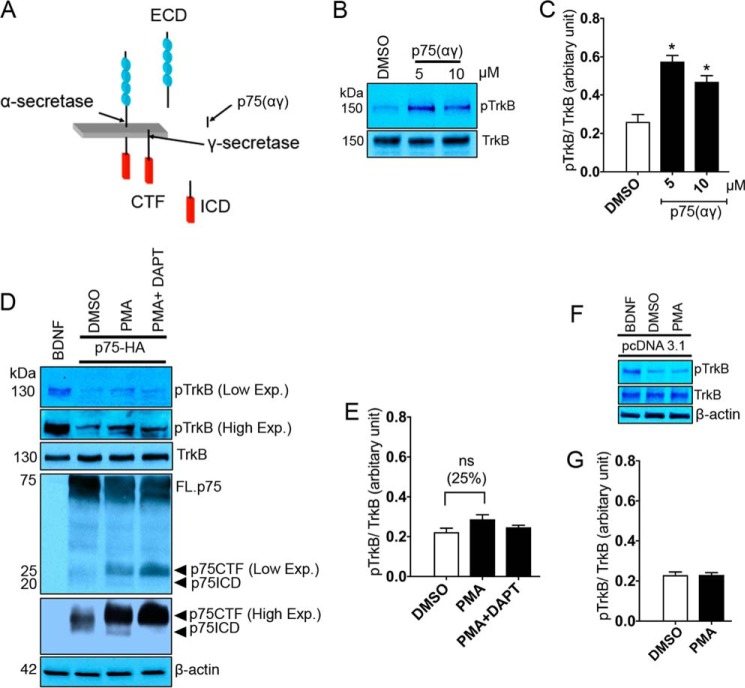

The transmembrane domain of p75, once liberated by intramembranous cleavage, enhances TrkB phosphorylation

Valine residue 264 in p75 TM is implicated in triggering TrkB phosphorylation. This residue is located in a p75 fragment that is physiologically released after intramembranous cleavage, p75(αγ) (Fig. 7A) (3, 43). Therefore, we sought to determine whether the p75(αγ) peptide (Table 1) can also stimulate TrkB phosphorylation using an in vitro phosphorylation assay. Our results suggest that incubation of 0.2 μm solubilized TrkB protein with p75(αγ) dramatically promotes TrkB phosphorylation (Fig. 7, B and C). To determine whether these in vitro results translated to live cells, we transfected HEK293-TrkB cells with 2 μg p75-HA for 24 h. The cells were then treated for 45 min with either 100 ng/ml PMA, an activator of metalloproteases, thus promoting ectodomain cleavage of p75, or alternatively a combination of PMA and 10 μm N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT), a γ-secretase inhibitor (3, 44). Treatment with PMA enhanced TrkB phosphorylation in HEK293-TrkB transfected with p75 by 25% (Fig. 7, D and E, and supplemental Fig. S4), but not in HEK293-TrkB transfected with mock vector, pcDNA3.1 (Fig. 7, F and G). Simultaneous treatment of PMA with DAPT prevented intramembranous cleavage of p75 and any impact on TrkB phosphorylation (Fig. 7, D and E, and supplemental Fig. S4). The effects of PMA on TrkB phosphorylation in HEK293-TrkB transfected with p75 was not dramatic, which may be a result of inefficient p75 cleavage induced by PMA or differences in substrate specificity by α-secretases. In addition, the p75(αγ) peptide, like the ICD, is likely very labile and rapidly degraded (45). This result, along with our in vitro data, suggests that p75(αγ), as a product of intramembranous cleavage of p75, may induce TrkB activation in circumstances when these receptors are highly co-expressed during development or after neuronal injury.

Figure 7.

The transmembrane domain of p75, once liberated by intramembranous cleavage, enhances TrkB phosphorylation. A, schematic diagram represents that p75 is initially cleaved by ADAM17 leading to p75ECD and p75CTF generation. The CTF is further processed at an intramembranous site by γ-secretase, which generates p75ICD and p75(αγ). B and C, the Western blot and its quantification show the effects of 30-min incubation with 5 and 10 μm p75(αγ) on TrkB phosphorylation (Tyr816) using an in vitro phosphorylation assay. The ratio of 0.2 μm TrkB incubated with 5 and 10 μm p75(αγ) were 1:25, and 1:50, respectively (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05 versus DMSO. D, HEK293-TrkB cells were transfected with 2 μg of p75-HA for 24 h. The cells were then washed with PBS and treated for 45 min with either 100 ng/ml PMA or a combination of PMA and 10 μm DAPT. 20 μg of total protein was subjected to Western blot to detect phosphorylated (Tyr816) and total TrkB. The full-length p75 (FL.p75) and its fragments (p75CTF and ICD) were detected by rabbit anti-p75 (9992) antibody (3). Non-transfected HEK293-TrkB cells treated with 50 ng/ml BDNF over 30 min were used as positive control for phosphorylated TrkB antibody. E, representative quantification demonstrates the effects of PMA or PMA/DAPT on TrkB (Tyr816) phosphorylation. F and G, the Western blot and its quantification represent the effects of 100 ng/ml PMA for 45 min on TrkB phosphorylation in HEK293-TrkB cells transfected with mock vector, pcDNA3.1 (n = 3 individual experiments; means ± S.E.).

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the transmembrane domain of p75 could activate the TrkB receptor. In contrast, the transmembrane domain of other receptors failed to induce TrkB phosphorylation. We also tested whether other related the RTK members, including TrkA and TrkC, which have a high homology with TrkB (46, 47) and display similar structural domains, are affected by p75 TM. However, the p75 TM has a profound effect mainly on TrkB phosphorylation. Furthermore, we utilized co-immunoprecipitation and sucrose subcellular fractionation assays to explore how p75 TM may enhance TrkB phosphorylation. We found that p75 TM interacts with the TrkB receptor, and this association likely occurs in lipid rafts and the cell membrane. Moreover, mutagenesis revealed that a valine residue at position 264 in p75 TM was critical for the p75 TM-induced TrkB phosphorylation.

The p75 receptor undergoes similar cleavages as APP and Notch-1. It is cleaved first by ADAM17, leading to p75ECD and p75CTF (2). The CTF is processed at an intramembranous site by γ-secretase and generates p75ICD and a 26-amino acid peptide, p75(αγ), which covers 60% of the transmembrane domain (3). The transmembrane region of p75 is highly conserved across species, and it is known to influence NGF-binding kinetics (22).

Our in vitro assays results demonstrated that p75 TM enhances TrkB phosphorylation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Neither the EGFR TM nor the FGFR1 TM influenced TrkB phosphorylation. Moreover, p75 TM did not alter the phosphorylation of TrkA, TrkC, or FGFR1 receptors. These results altogether suggest a level of specificity for TrkB activation by p75 TM.

To minimize any possible effects on TrkB phosphorylation by detergents, we removed detergents from the TrkB buffer and reconstituted the receptor in brain lipids to form proteoliposomes and provide a more natural context for the effect of p75 TM on TrkB phosphorylation. The data indicate that p75 TM is capable of triggering TrkB phosphorylation in proteoliposomes in the absence of detergent. Taken together, these experiments suggest that the TM domain of p75 may have a signaling function, in addition to anchoring the receptor in the membrane. The observed effect of the TrkB TM on TrkB phosphorylation and the recent report on the effect of insulin receptor TM on insulin receptor phosphorylation (20) suggest that there are likely transmembrane domains that have additional functions dependent upon sequence specific interactions.

Alterations of TM sequences in the p75 receptor revealed important amino acid residues in p75 TM important for stimulating TrkB phosphorylation. A structural study on p75 TM using nuclear magnetic resonance has shown that cysteine 257 in p75 TM participates in receptor dimerization through a disulfide bond and promotes p75 ligand-dependent signaling downstream, resulting in greater cell survival (39). However, our experiments using a mutation in p75 TM, p75C257A, suggest that cysteine 257 is not critical for p75 TM-induced TrkB phosphorylation, because the p75C257A peptide was still able to enhance TrkB activity. In contrast, we found that a specific mutation in p75V264A in the AVVVG motif, which has no predicted effect on α-helix preference, abolished p75 TM-induced TrkB phosphorylation. This suggests that valine 264, which is known to be adjacent to the site of intramembrane proteolysis of p75 catalyzed by the γ-secretase complex, plays a crucial role in inducing TrkB phosphorylation (3, 43).

Valine 264 is located in a p75 fragment, p75(αγ), which is released after intramembranous cleavage (3, 43), and the in vitro phosphorylation assay suggested that p75(αγ) peptide can alone stimulate TrkB phosphorylation; we then tested whether the activation of metalloprotease by PMA to promote sequential cleavage of p75 and generate the p75(αγ) fragment in cells could alter TrkB phosphorylation. Our data showed that the phosphorylation of TrkB in HEK293-TrkB cells expressing p75 was enhanced by 25% in response to PMA treatment, which is not a statistically significant increase. This could be due to low efficiency of the effects of PMA upon α-secretase cleavage and the lack of sufficient substrate required for γ-secretase activity. Differences in substrate specificity or cellular environment and characteristics, such as lipid composition, may also exert an effect upon the efficiency of cleavage (3). Furthermore, it is known that the p75 ICD peptide degrades rapidly; as such, it is likely that p75(αγ) does as well (45).

In conclusion, our study in vitro and within live cells suggest that p75 TM and p75(αγ) may impact TrkB activation in circumstances where these receptors' expression levels are increased and when cleavage is maximal. Based upon these results, it is conceivable that small molecules that interact with transmembrane domains may possess agonistic qualities, as has been observed with the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (48). Additional in vivo studies will be needed to determine whether TrkB activation by small peptides can represent a therapeutic strategy.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and transfections

The human embryonic kidney 293 cell line stably expressing human TrkB (HEK293-TrkB) (49) was maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mm glutamine, and 200 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (Sf9) cells were grown in ESF921 insect cell culture medium (Expression System, Davis, CA) and maintained in monolayer cultures shaken at 95 rpm for 72 h. HEK293-TrkB cells were transfected with 2 μg of rat p75-HA plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000TM (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Peptides, antibodies, and reagents

All peptides including rat p75 TM, p75C257A, p75GRA, p75V263A, p75V264A, p75 TM-HA, p75V264A-HA, p75(αγ), TAT-HA, rat TrkB TM, human EGFR TM, and human FGFR1 TM with ≥70% purity, were synthesized by Biomatik (Wilmington, DE) (Table 1). Rabbit anti-p75 (9992) (3), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-TrkA (Y816) (50), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-TrkB (Y816) (35), sheep polyclonal anti-phospho-TrkC (Y820) (ab79811) (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-FGFR (Y653/Y654) (55H2) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), rabbit polyclonal TrkB (H-181) (Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal pan Trk (C-14) (Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-FGFR (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal anti-HA (12CA5) (Roche Diagnostics), mouse monoclonal anti-early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) (Sigma), mouse polyclonal anti-flotillin-1 (BD Transduction Laboratories, Billerica, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+/K+-ATPase (Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (Sigma) were used as primary antibodies. Normal mouse and rabbit IgG (Sigma), mouse, and rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma) were used in this study. BDNF was purchased from Peprotech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and DAPT were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Tyrosine kinase receptors expression and solubilization

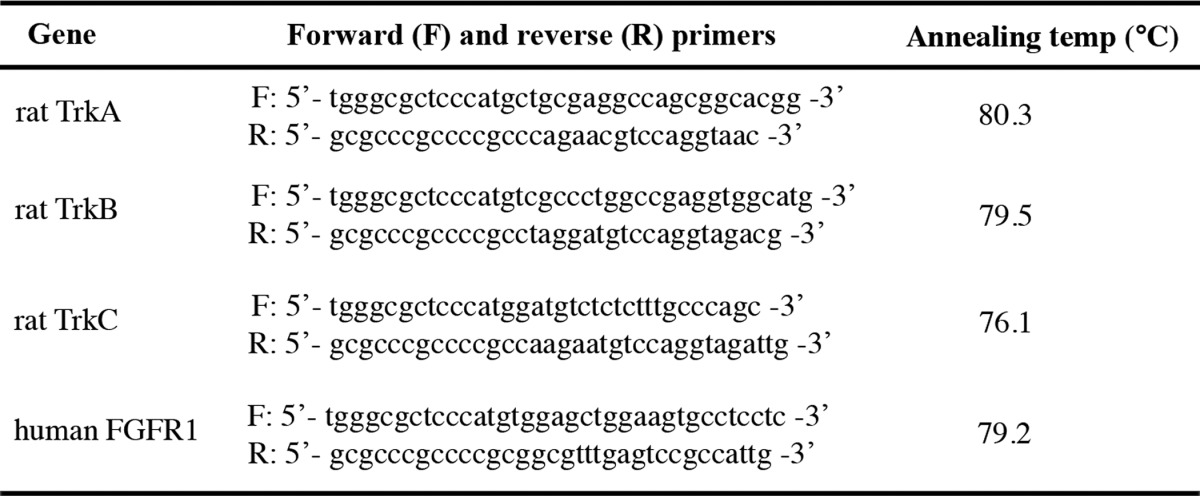

Rat TrkA, TrkB, TrkC (51), and human FGFR1 (from Prof. Dalibor Sames, Columbia University, New York, NY) with a carboxyl-terminal GFP were synthesized and subcloned in the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions using PCR and primers (Table 2).

Table 2.

PCR primer pair sequences used for cloning tyrosine kinase receptors in Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system

Sf9 cells were transfected with bacmid plasmids using Cellfectin II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions to obtain recombinant P1 baculoviruses. Sf9 cells were infected with P1 to generate P2 viruses. The cells were subsequently infected with P2 to obtain P3 viruses with the required titer level. Eventually Sf9 cells were infected with P3 viruses and left at 27 °C for 72 h to express TrkA, TrkB, TrkC, and FGFR1 (Figs. 1A and 2, A–C). The cells were harvested in the solubilization buffer, which contained PBS, 1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside detergent (Sigma), protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and 2 mm PMSF (Sigma), and kept on ice at 4 °C for 2 h. The cells were then subjected to sonication followed by high-speed centrifugation at 39,000 rpm/40 min to solubilize the transmembrane proteins.

In vitro phosphorylation assay

The solubilization buffer of Sf9 lysates was dialyzed to phosphorylation buffer which contained 25 mm HEPES, 15 mm MgCl2, 10 mm MnCl2, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100 by overnight dialysis at 4 °C using 10,000 molecular weight cutoff dialysis cassettes (Rockford). The total protein was measured by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and subsequently flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen. The samples were kept at −80 °C until use.

Because of high hydrophobicity, all peptides were dissolved in DMSO (Fisher Scientific) and were further diluted in distilled H2O. To investigate whether the peptides could induce tyrosine kinase receptor phosphorylation, TM peptides were incubated with TrkA, TrkB, TrkC, and FGFR1 proteins in the presence of 25 μm ATP on a rotator at 37 °C. To stop phosphorylation reactions, SDS-loading buffer was added to the samples and boiled for 5 min. A dose-dependent and time course effect of TM peptides on receptor phosphorylation was detected by Western blot. To detect the total protein as a loading control for phosphorylated receptors, the membrane was stripped with 0.2 m glycine and 1% SDS for 15 min, blocked, and incubated with anti-TrkA, TrkB, TrkC, and FGFR1 antibodies (52, 53).

Proteoliposome assay

Porcine brain lipid in chloroform (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) was transferred into a glass test tube and dried by N2 until a lipid film appeared. The lipids were further dried under vacuum for 2 h. The lipids were rehydrated in phosphorylation buffer supplemented with 4% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside and mixed with solubilized TrkB with a lipid protein ratio of 12.5 (w/w). Detergents were subsequently removed from the samples by overnight incubation with 600 mg of Bio-Beads SM2 resin (Bio-Rad) at 4 °C (37). The proteoliposomes containing TrkB were isolated using high-speed centrifugation, 50,000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C. The proteoliposome pellet was resuspended in phosphorylation buffer without Triton X-100. The samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analyzed. Electron microscopy of negatively stained samples (Fig. 3A) and SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue (R250) staining (Fig. 3B) were utilized to confirm TrkB proteoliposome formation (54, 55).

Co-immunoprecipitation

p75 TM-HA or p75V264A-HA or TAT-HA peptides (10 μg) were premixed with 250 μg of solubilized Sf9-TrkB in 500 μl of Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at 4 °C for 2 h before co-IP. The premixed p75 TM-HA/TrkB or p75V264A-HA/TrkB or TAT-HA/TrkB lysates were incubated with 1 μg of either mouse anti-HA or rabbit anti-TrkB (H-181) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Mouse and rabbit IgG served as negative controls for antibody pulldown in co-IP experiments. Subsequently, protein A-agarose beads (Sigma) were used to immobilize the antibodies and IgG. The beads were then washed four times with 0.01% Tween 20 in TBS (TBST), boiled in SDS loading buffer, and subjected to Western blot. 10 μg of sample lysate was loaded as a comparative (input) control.

Sucrose subcellular fractionation

HEK293-TrkB cells were mechanically lysed in TBS supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture and 2 mm PMSF by passing the sample through a 27-gauge needle six times (Sigma). The lysate was then subjected to centrifugation at 100 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was isolated, and the total protein was measured by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). 150 μg of HEK293-TrkB cell supernatants were premixed with 10 μg of p75 TM-HA at 4 °C for 2 h prior to sucrose fractionation. The premixed sample was loaded on top of a continuous 12.5–50% sucrose/TBS gradient and centrifuged at 31,000 rpm for 3 h at 4 °C using a SW60 rotor (Beckman). An equal volume of each fraction was taken and subjected to Western blot using 4–15% Tris-glycine and 16.5% Tris-Tricine precast gels (Bio-Rad). The membrane was probed with anti-TrkB (H-181), anti-HA (p75 TM-HA), anti-Flotilin-1 (protein marker for lipid raft), anti-Na+/K+-ATPase (cell membrane marker), anti-EEA1 (protein marker for early endosome), and anti-β-actin (a cytosolic marker) antibodies (56).

Western blot

The concentration of total protein isolated from Sf9, Sf9-TrkB, and HEK293-TrkB was measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). 20–30 μg of the protein was separated by either 4–15% Tris-glycine precast gels (Bio-Rad) or 4–12% Bis-Tris precast gels (Invitrogen). 16.5% Tris-Tricine precast gels (Bio-Rad) were used to separate small peptides like p75 TM-HA, p75V264A-HA, and TAT-HA by electrophoresis. The proteins and peptides were transferred to a 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked by 3% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature (22 °C) and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in 3% BSA in TBST (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in 3% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed with TBST and developed with a Kodak X-OMAT 2000 machine (Rochester, NY) using chemiluminescence reagents (GE Healthcare) and X-ray film (GeneMate, Kaysville, UT).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 provided by New York University School of Medicine. Variables between groups were determined by either one-way repeated measures analysis of variance or Student's t test. The values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data are presented as means ± S.E.

Author contributions

M. V. C. conceived and supervised the project; K. S. designed and performed most experiments and data analysis; M. M., S. P., S. A., and M. L. L.-R. contributed by performing parts of experiments; K. S. and M. V. C. wrote the manuscript. D. L. S. contributed to experimental design and scientific discussions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dalibor Sames (Department of Chemistry, Columbia University) for providing human FGFR1 plasmid. We also thank Dr. Da-Neng Wang and Dr. David Sauer (Department of Structural Biology, New York University School of Medicine) for sharing reagents and helping with the RTK purification from Sf9 cells.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AG025970. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- ECD

- ectodomain

- CTF

- carboxyl-terminal fragment

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- TM

- transmembrane

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- co-IP

- co-immunoprecipitation

- EEA

- early endosome antigen

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- DAPT

- N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline.

References

- 1. De Strooper B. (2003) Aph-1, Pen-2, and Nicastrin with presenilin generate an active γ-secretase complex. Neuron 38, 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weskamp G., Schlöndorff J., Lum L., Becherer J. D., Kim T. W., Saftig P., Hartmann D., Murphy G., and Blobel C. P. (2004) Evidence for a critical role of the tumor necrosis factor α convertase (TACE) in ectodomain shedding of the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4241–4249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zampieri N., Xu C. F., Neubert T. A., and Chao M. V. (2005) Cleavage of p75 neurotrophin receptor by α-secretase and γ-secretase requires specific receptor domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14563–14571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rao M. S., and Anderson D. J. (1997) Immortalization and controlled in vitro differentiation of murine multipotent neural crest stem cells. J. Neurobiol. 32, 722–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cragnolini A. B., and Friedman W. J. (2008) The function of p75NTR in glia. Trends Neurosci. 31, 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lin Z., Tann J. Y., Goh E. T., Kelly C., Lim K. B., Gao J. F., and Ibanez C. F. (2015) Structural basis of death domain signaling in the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Elife 4, e11692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He X. L., and Garcia K. C. (2004) Structure of nerve growth factor complexed with the shared neurotrophin receptor p75. Science 304, 870–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vilar M., Charalampopoulos I., Kenchappa R. S., Simi A., Karaca E., Reversi A., Choi S., Bothwell M., Mingarro I., Friedman W. J., Schiavo G., Bastiaens P. I., Verveer P. J., Carter B. D., and Ibáñez C. F. (2009) Activation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor through conformational rearrangement of disulphide-linked receptor dimers. Neuron 62, 72–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anastasia A., Barker P. A., Chao M. V., and Hempstead B. L. (2015) Detection of p75NTR trimers: implications for receptor stoichiometry and activation. J. Neurosci. 35, 11911–11920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reichardt L. F. (2006) Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361, 1545–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bibel M., Hoppe E., and Barde Y. A. (1999) Biochemical and functional interactions between the neurotrophin receptors trk and p75NTR. EMBO J. 18, 616–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schecterson L. C., and Bothwell M. (2008) An all-purpose tool for axon guidance. Sci. Signal. 1, pe50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nykjaer A., Lee R., Teng K. K., Jansen P., Madsen P., Nielsen M. S., Jacobsen C., Kliemannel M., Schwarz E., Willnow T. E., Hempstead B. L., and Petersen C. M. (2004) Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature 427, 843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yao X. Q., Jiao S. S., Saadipour K., Zeng F., Wang Q. H., Zhu C., Shen L. L., Zeng G. H., Liang C. R., Wang J., Liu Y. H., Hou H. Y., Xu X., Su Y. P., Fan X. T., et al. (2015) p75NTR ectodomain is a physiological neuroprotective molecule against amyloid-β toxicity in the brain of Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Psychiatry 20, 1301–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanning K. C., Hudson M., Amieux P. S., Wiley J. C., Bothwell M., and Schecterson L. C. (2003) Proteolytic processing of the p75 neurotrophin receptor and two homologs generates C-terminal fragments with signaling capability. J. Neurosci. 23, 5425–5436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parkhurst C. N., Zampieri N., and Chao M. V. (2010) Nuclear localization of the p75 neurotrophin receptor intracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5361–5368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Selkoe D. J. (1996) Amyloid β-protein and the genetics of Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18295–18298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hardy J., and Selkoe D. J. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kasuga K., Kaneko H., Nishizawa M., Onodera O., and Ikeuchi T. (2007) Generation of intracellular domain of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase by γ-secretase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 360, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee J., Miyazaki M., Romeo G. R., and Shoelson S. E. (2014) Insulin receptor activation with transmembrane domain ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19769–19777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bothwell M. (2006) Evolution of the neurotrophin signaling system in invertebrates. Brain Behav. Evol. 68, 124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Esposito D., Patel P., Stephens R. M., Perez P., Chao M. V., Kaplan D. R., and Hempstead B. L. (2001) The cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of the p75 and Trk A receptors regulate high affinity binding to nerve growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32687–32695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chao M. V., and Hempstead B. L. (1995) p75 and Trk: a two-receptor system. Trends Neurosci. 18, 321–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Autry A. E., and Monteggia L. M. (2012) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 64, 238–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu B., Nagappan G., Guan X., Nathan P. J., and Wren P. (2013) BDNF-based synaptic repair as a disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 401–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kang H., and Schuman E. M. (1995) Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science 267, 1658–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J., Tanoue A., Wu C., and Mobley W. C. (2006) TrkB binds and tyrosine-phosphorylates Tiam1, leading to activation of Rac1 and induction of changes in cellular morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10444–10449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Minichiello L. (2009) TrkB signalling pathways in LTP and learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 850–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cowley S., Paterson H., Kemp P., and Marshall C. J. (1994) Activation of MAP kinase kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell 77, 841–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meakin S. O., MacDonald J. I., Gryz E. A., Kubu C. J., and Verdi J. M. (1999) The signaling adapter FRS-2 competes with Shc for binding to the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA. A model for discriminating proliferation and differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9861–9870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chao M. V. (2003) Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang E. J., and Reichardt L. F. (2001) Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 677–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hempstead B. L., Martin-Zanca D., Kaplan D. R., Parada L. F., and Chao M. V. (1991) High-affinity NGF binding requires coexpression of the trk proto-oncogene and the low-affinity NGF receptor. Nature 350, 678–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benedetti M., Levi A., and Chao M. V. (1993) Differential expression of nerve growth factor receptors leads to altered binding affinity and neurotrophin responsiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 7859–7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arévalo J. C., Waite J., Rajagopal R., Beyna M., Chen Z. Y., Lee F. S., and Chao M. V. (2006) Cell survival through Trk neurotrophin receptors is differentially regulated by ubiquitination. Neuron 50, 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soppet D., Escandon E., Maragos J., Middlemas D. S., Reid S. W., Blair J., Burton L. E., Stanton B. R., Kaplan D. R., Hunter T., Nikolics K., and Parada L. F. (1991) The neurotrophic factors brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 are ligands for the trkB tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell 65, 895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lévy D., Bluzat A., Seigneuret M., and Rigaud J. L. (1990) A systematic study of liposome and proteoliposome reconstitution involving Bio-Bead-mediated Triton X-100 removal. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1025, 179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pereira D. B., and Chao M. V. (2007) The tyrosine kinase Fyn determines the localization of TrkB receptors in lipid rafts. J. Neurosci. 27, 4859–4869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nadezhdin K. D., García-Carpio I., Goncharuk S. A., Mineev K. S., Arseniev A. S., and Vilar M. (2016) Structural basis of p75 transmembrane domain dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 12346–12357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vilar M., Charalampopoulos I., Kenchappa R. S., Reversi A., Klos-Applequist J. M., Karaca E., Simi A., Spuch C., Choi S., Friedman W. J., Ericson J., Schiavo G., Carter B. D., and Ibáñez C. F. (2009) Ligand-independent signaling by disulfide-crosslinked dimers of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3351–3357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sykes A. M., Palstra N., Abankwa D., Hill J. M., Skeldal S., Matusica D., Venkatraman P., Hancock J. F., and Coulson E. J. (2012) The effects of transmembrane sequence and dimerization on cleavage of the p75 neurotrophin receptor by γ-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43810–43824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Juretić D., Lee B., Trinajstić N., and Williams R. W. (1993) Conformational preference functions for predicting helices in membrane proteins. Biopolymers 33, 255–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jung K. M., Tan S., Landman N., Petrova K., Murray S., Lewis R., Kim P. K., Kim D. S., Ryu S. H., Chao M. V., and Kim T. W. (2003) Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of the p75 neurotrophin receptor modulates its association with the TrkA receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42161–42169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dovey H. F., John V., Anderson J. P., Chen L. Z., de Saint Andrieu P., Fang L. Y., Freedman S. B., Folmer B., Goldbach E., Holsztynska E. J., Hu K. L., Johnson-Wood K. L., Kennedy S. L., Kholodenko D., Knops J. E., et al. (2001) Functional γ-secretase inhibitors reduce β-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J. Neurochem. 76, 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Domeniconi M., Zampieri N., Spencer T., Hilaire M., Mellado W., Chao M. V., and Filbin M. T. (2005) MAG induces regulated intramembrane proteolysis of the p75 neurotrophin receptor to inhibit neurite outgrowth. Neuron 46, 849–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lamballe F., Klein R., and Barbacid M. (1991) trkC, a new member of the trk family of tyrosine protein kinases, is a receptor for neurotrophin-3. Cell 66, 967–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Klein R., Parada L. F., Coulier F., and Barbacid M. (1989) trkB, a novel tyrosine protein kinase receptor expressed during mouse neural development. EMBO J. 8, 3701–3709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neumann S., Padia U., Cullen M. J., Eliseeva E., Nir E. A., Place R. F., Morgan S. J., and Gershengorn M. C. (2016) An enantiomer of an oral small-molecule TSH receptor agonist exhibits improved pharmacologic properties. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 7, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Narisawa-Saito M., Iwakura Y., Kawamura M., Araki K., Kozaki S., Takei N., and Nawa H. (2002) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates surface expression of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid receptors by enhancing the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2 interaction in developing neocortical neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40901–40910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rajagopal R., Chen Z. Y., Lee F. S., and Chao M. V. (2004) Transactivation of Trk neurotrophin receptors by G-protein-coupled receptor ligands occurs on intracellular membranes. J. Neurosci. 24, 6650–6658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yano H., Cong F., Birge R. B., Goff S. P., and Chao M. V. (2000) Association of the Abl tyrosine kinase with the Trk nerve growth factor receptor. J. Neurosci. Res. 59, 356–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deyev I. E., Mitrofanova A. V., Zhevlenev E. S., Radionov N., Berchatova A. A., Popova N. V., Serova O. V., and Petrenko A. G. (2013) Structural determinants of the insulin receptor-related receptor activation by alkali. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 33884–33893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kitamura T., Kitamura Y., Kuroda S., Hino Y., Ando M., Kotani K., Konishi H., Matsuzaki H., Kikkawa U., Ogawa W., and Kasuga M. (1999) Insulin-induced phosphorylation and activation of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3B by the serine-threonine kinase Akt. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 6286–6296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Simeonov P., Werner S., Haupt C., Tanabe M., and Bacia K. (2013) Membrane protein reconstitution into liposomes guided by dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. Chem. 184, 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Neves P., Lopes S. C., Sousa I., Garcia S., Eaton P., and Gameiro P. (2009) Characterization of membrane protein reconstitution in LUVs of different lipid composition by fluorescence anisotropy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 49, 276–28119121912 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Uldry M., Steiner P., Zurich M. G., Béguin P., Hirling H., Dolci W., and Thorens B. (2004) Regulated exocytosis of an H+/myo-inositol symporter at synapses and growth cones. EMBO J. 23, 531–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.