Abstract

SLC30A10 and SLC39A14 are manganese efflux and influx transporters, respectively. Loss-of-function mutations in genes encoding either transporter induce hereditary manganese toxicity. Patients have elevated manganese in the blood and brain and develop neurotoxicity. Liver manganese is increased in patients lacking SLC30A10 but not SLC39A14. These organ-specific changes in manganese were recently recapitulated in knockout mice. Surprisingly, Slc30a10 knockouts also had elevated thyroid manganese and developed hypothyroidism. To determine the mechanisms of manganese-induced hypothyroidism and understand how SLC30A10 and SLC39A14 cooperatively mediate manganese detoxification, here we produced Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout mice and compared their phenotypes with that of Slc30a10 single knockouts. Compared with wild-type controls, Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts had higher manganese levels in the blood and brain but not in the liver. In contrast, Slc30a10 single knockouts had elevated manganese levels in the liver as well as in the blood and brain. Furthermore, SLC30A10 and SLC39A14 localized to the canalicular and basolateral domains of polarized hepatic cells, respectively. Thus, transport activities of both SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 are required for hepatic manganese excretion. Compared with Slc30a10 single knockouts, Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts had lower thyroid manganese levels and normal thyroid function. Moreover, intrathyroid thyroxine levels of Slc30a10 single knockouts were lower than those of controls. Thus, the hypothyroidism phenotype of Slc30a10 single knockouts is induced by elevated thyroid manganese, which blocks thyroxine production. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of manganese detoxification and manganese-induced thyroid dysfunction.

Keywords: liver, manganese, metal homeostasis, thyroid, transporter, SLC30, SLC39, cation diffusion facilitator, excretion, parkinsonism

Introduction

Manganese is an essential metal that becomes toxic at elevated levels (1). When systemic levels increase, the metal accumulates in the brain, particularly in the basal ganglia, and induces neurotoxicity (1–4). The primary manifestation of manganese toxicity in occupationally exposed adults is the onset of a parkinsonian-like movement disorder (1, 3, 4). Recent epidemiological studies in human populations, along with assays in rodents, suggest that exposure to elevated manganese during early life induces behavioral, cognitive, and motor defects (5–17). In addition to elevated exposure, manganese toxicity may also occur because of decreased excretion. Indeed, as manganese is primarily eliminated via bile, patients with defective liver function because of cirrhosis or other diseases fail to excrete manganese and may suffer from manganese neurotoxicity in the absence of exposure to elevated manganese (2).

Over the last few years, two disorders of manganese metabolism that led to the retention of manganese in the body and induced neurotoxicity were discovered. In 2012, homozygous loss of function mutations in SLC30A10 were reported to increase manganese levels in the blood, brain, and liver and induce neurotoxicity (18–21). We recently reported that similar increases in blood, brain, and liver manganese occurred in Slc30a10 knockout mice (22). At the cellular level, our work revealed that the WT SLC30A10 protein functioned as a cell surface–localized manganese efflux transporter that reduced intracellular manganese levels and protected against manganese toxicity (23, 24). Disease-causing mutations blocked the intracellular trafficking and manganese efflux function of the transporter (23), enhancing sensitivity to manganese toxicity.

Separately, in 2016, mutations in SLC39A14 (also called ZIP14) were also reported to increase manganese levels in the blood and brain (but not in the liver; see below) and induce neurotoxicity in humans (25). Similar organ-specific changes in manganese levels were recently reported in Slc39a14 knockout mice (26, 27). Prior studies identified SLC39A14 as an influx transporter with the capability to transport manganese, zinc, iron, and cadmium to the cytosol of cells (28–33). Importantly, in human patients with mutations in SLC39A14, manganese levels were elevated in the blood and brain, but levels of iron, zinc, and cadmium in the blood were unaltered (25). Additionally, transport assays in cells demonstrated that disease-causing mutations inhibited the capability of SLC39A14 to mediate manganese influx (25). Overall, loss of the manganese transport capacity of SLC39A14 was implicated in increasing body manganese levels and inducing toxicity in patients harboring disease-causing mutations (25).

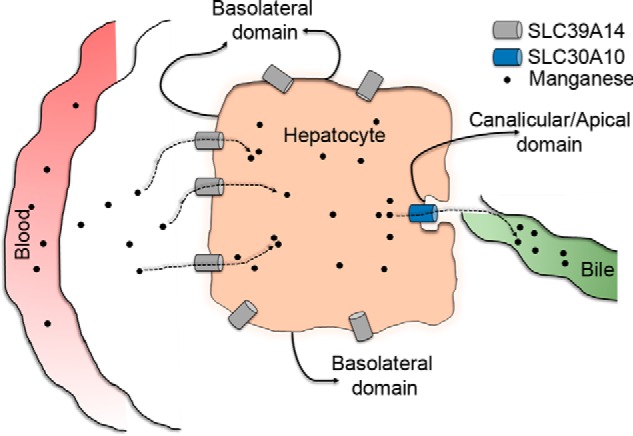

The mechanism by which loss of function of either an efflux transporter, SLC30A10, or an influx transporter, SLC39A14, may increase blood and brain manganese levels may rely on their activities in the liver. A proposed model is that SLC39A14 may mediate the influx of manganese from blood into hepatocytes, and SLC30A10 may subsequently mediate the efflux of manganese into bile (Fig. 1) (25–27, 34). This model needs to be experimentally verified (part of this study) but is consistent with the observation that depletion of SLC30A10, but not SLC39A14, enhanced liver manganese and induced liver pathology in humans and mice (18–22, 25–27).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the localization and function of SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 in polarized hepatocytes.

While working on Slc30a10 knockout mice, we made the completely unexpected discovery that these knockouts developed severe hypothyroidism (22). After weaning, Slc30a10 knockout mice failed to thrive and died prematurely (∼6–8 weeks of age) (22). By 6 weeks of age, serum thyroxine levels of Slc30a10 knockouts were ∼50–80% lower than that of littermate controls, whereas serum thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were ∼800–1000-fold greater (22). As thyroid hormone has profound effects on neurological function (35, 36), the unanticipated phenotype of Slc30a10 knockouts raises the possibility that thyroid dysfunction may be an unappreciated but clinically relevant aspect of manganese toxicity. A direct implication is that elucidating the mechanisms of hypothyroidism is now an essential step in understanding the pathobiology of manganese-induced disease in humans.

To gain insights into the mechanisms that induce hypothyroidism in Slc30a10 knockouts and better comprehend the process by which SLC30A10 and SLC39A14 cooperatively regulate manganese homeostasis, we generated mice lacking both Slc30a10 and Slc39a14 (double knockouts) and compared their phenotype with mice lacking either Slc30a10 only or Slc39a14 only (single knockouts). Our results show that SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 act synergistically to mediate hepatic manganese detoxification and that the hypothyroidism phenotype of Slc30a10 single knockouts is a consequence of manganese-induced inhibition of thyroxine production in the thyroid. These findings provide important new insights into the mechanisms of manganese detoxification and induced thyroid dysfunction and enhance our understanding of the biology of manganese homeostasis and toxicity.

Results

Manganese levels are elevated in the blood and brain, but not liver, of Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts

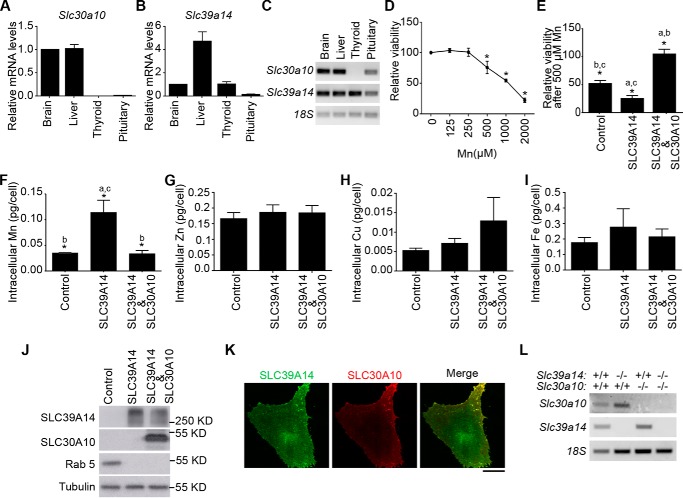

We demonstrated previously that manganese levels were elevated in the brain, pituitary, and thyroid of Slc30a10 single knockout mice (22). Hypothyroidism may occur because of changes in the thyroid or secondary to those in the brain or pituitary (36). Hypothyroidism because of pituitary dysfunction is generally associated with normal or decreased serum thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (36), but in Slc30a10−/− mice, thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were profoundly elevated (22), implying that pituitary function was not compromised. However, our previous work could not determine whether the thyroid dysfunction observed in Slc30a10 single knockouts occurred because of manganese-induced deficits in the brain or thyroid. To address this important question, the ideal experiment would have been to characterize a thyroid-specific Slc30a10 knockout. However, we did not detect Slc30a10 expression at the RNA level in the thyroid of wild-type mice (Fig. 2, A and C), suggesting that elevations in thyroid manganese levels likely occurred secondary to increased blood manganese evident in this strain (22), and raising doubts regarding whether a thyroid-specific knockout would provide meaningful data. Therefore, we instead sought to deplete a manganese importer that was expressed in the thyroid. We selected Slc39a14 for the reasons described below. Slc39a14 was robustly expressed in the mouse thyroid, albeit at a level lower than in the liver (Fig. 2, B and C). This finding was consistent with a previous report (37) and suggested that Slc39a14 may play a role in importing manganese into the thyroid. We also rigorously validated the manganese influx capability of SLC39A14 in culture. Transfection of SLC39A14WT enhanced the sensitivity of HeLa cells to manganese-induced death (Fig. 2, D and E). This effect was reversed when SLC30A10WT was co-transfected (Fig. 2E). Compared with transfection control, intracellular manganese levels were greater in HeLa cells transfected with SLC39A14WT but not in those co-transfected with SLC39A14WT and SLC30A10WT (Fig. 2F). The levels of zinc, copper, and iron were comparable between transfection conditions (Fig. 2, G–I), suggesting that SLC39A14 predominantly transported manganese in these cells. Note that prior work in cell culture, Caenorhabditis elegans, and mice demonstrated that SLC30A10 was a specific manganese transporter (22–24, 38, 39). We verified that, after transfection, SLC39A14WT and SLC30A10WT were well-expressed and that, consistent with prior results (23, 24, 28, 30–32, 40), both transporters robustly trafficked to the cell surface (Fig. 2, J and K). The cell culture data supported the idea that Slc39a14 may be important for the influx of manganese into thyroid cells. Finally, depletion of SLC39A14 in humans and mice was already reported to increase manganese levels in the blood and brain (25–27). Changes in thyroid manganese were unknown, but the available data implied that SLC39A14 played a role in regulating manganese homeostasis at the organism level.

Figure 2.

Expression and transport activity of SLC39A14 and SLC30A10. A–C, 6-week-old wild-type mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide. RNA was extracted from tissues. After this, samples were used to quantify mRNA levels using quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR analyses (A and B; normalized mRNA levels of Slc30a10 or Slc39a14 in brain were expressed as 1) or processed for reverse transcription PCR (C) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3 animals). D, HeLa cells were treated with indicated amounts of manganese for 16 h, and viability was assessed as described under “Materials and methods.” Viability of cells treated with 0 μm manganese was set to 100 (mean ± S.E.; n = 3; *, p < 0.05 for the difference between 0 μm manganese and other groups using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test). E, HeLa cells were transfected with indicated constructs. One day post-transfection, cultures were treated with 0 or 500 μm manganese for 16 h. Viability was then assessed. For each transfection condition, viability without manganese treatment was independently normalized to 100 and used to calculate relative viability after manganese exposure (mean ± S.E.; n = 3–5/transfection condition; *, p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc test, with a, b, and c indicating differences in comparison with cells transfected with control, SLC39A14, or SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 constructs, respectively). F–I, HeLa cells were transfected with indicated constructs. As described under “Materials and methods,” the control construct coded for Rab5-GFP. After 24 h, cultures were exposed to 125 μm manganese for 16 h. Cells were then collected, and absolute amounts of intracellular manganese (F), zinc (G), copper (H), and iron (I) were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (mean ± S.E.; n = 4/transfection condition; *, p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc test, with a, b, and c indicating differences in comparison with cells transfected with control, SLC39A14, or SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 constructs, respectively). J, HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-Rab5 (used as a control), GFP-SLC39A14WT, or GFP-SLC39A14WT and FLAG-SLC30A10WT. Two days after transfection, samples were processed for immunoblot analyses to detect GFP, FLAG, and tubulin. K, HeLa cells were co-transfected with GFP-SLC39A14WT and FLAG-SLC30A10WT. After 48 h, immunofluorescence analyses were performed to detect GFP and FLAG. Scale bar = 20 μm. L, mice of indicated genotypes were euthanized at 6 weeks of age. Samples of the liver were processed for reverse transcription PCR analyses.

We recovered a previously described full-body, constitutive Slc39a14 single knockout strain using cryopreserved sperm available from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (see details under “Materials and methods”) (41). We have recently described the generation of full-body, constitutive Slc30a10 single knockout mice (22). We then generated mice lacking both Slc39a14 and Slc30a10 by crossing Slc39a14+/− and Slc30a10+/− mice and intercrossing progeny that were heterozygous for both genes (see details under “Materials and methods”). For most assays in this report, we used animals of five genotypes produced by our breeding strategy: littermate wild-type controls (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/+), Slc39a14 heterozygous (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/−), Slc39a14 single knockouts (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14−/−), Slc30a10 single knockouts (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14+/+), and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14−/−). All mutant animals were produced at expected Mendelian ratios. We routinely genotyped animals by performing PCR from genomic DNA extracted from tail snips using gene-specific primers to amplify either the wild-type or knockout allele (see details under “Materials and methods”). To validate the genotype, we performed RT-PCR analyses on liver samples; both SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 were strongly expressed in the liver (Fig. 2, A–C). RT-PCR confirmed that Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10 single knockouts exhibited loss of SLC39A14 or SLC30A10 mRNA, respectively, whereas Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts exhibited loss of both gene products (Fig. 2L).

As the first experimental step in mice for this study, we analyzed metal levels in the blood, brain, and liver of 6-week-old animals. This time point was ideal because manganese toxicity led to premature death in Slc30a10 single knockouts at ages beyond 6 weeks, and we previously analyzed a large cohort of Slc30a10 single knockouts at this age (22), permitting direct comparisons between current and prior data. Additionally, our initial focus was on the blood, brain, and liver instead of the thyroid, for two reasons. First, this approach would allow us to recapitulate recently reported changes in manganese levels in these tissues in the single knockouts (22, 26, 27) and ensure that unexpected phenotypic alterations did not occur in the mutants used here. Second, we anticipated that the double knockouts would have lower liver and thyroid manganese than Slc30a10 single knockouts. Validation of this prediction in the liver would provide confidence in pursuing more challenging analyses of the thyroid gland.

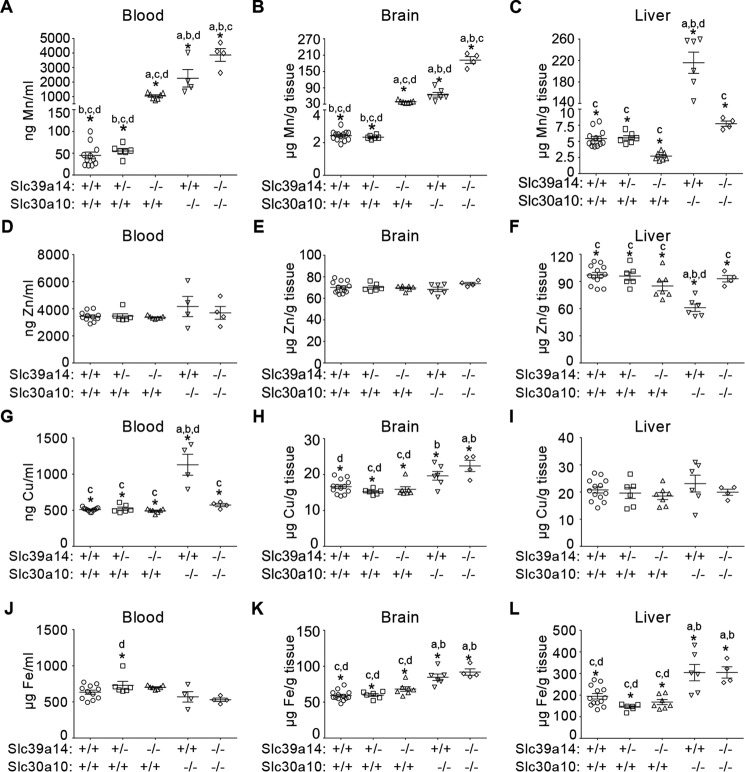

In Slc39a14 single knockouts, blood and brain manganese levels were ∼15–20-fold higher than in wild types (Fig. 3, A and B). Compared with Slc30a10 single knockouts, blood and brain manganese levels of Slc39a14 single knockouts were ∼40–50% lower (Fig. 3, A and B). Blood and brain manganese levels of the double knockouts were ∼80-fold higher than those of wild types and significantly greater than those of either single knockout (Fig. 3, A and B). Importantly, unlike Slc30a10 single knockouts, there was no increase in liver manganese in Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts (Fig. 3C). In all tissues, manganese levels were comparable between wild-type and Slc39a14 heterozygous mice (Fig. 3, A–C). Although some genotype-specific changes in levels of iron, copper, or zinc were observed, compared with manganese, these were relatively minor (Fig. 3, D–L); these changes were likely secondary to those observed with manganese. Thus, loss of Slc39a14 inhibits the elevation in liver manganese levels otherwise evident in mice lacking Slc30a10.

Figure 3.

Manganese levels are elevated in the blood and brain, but not in the liver, of mice lacking Slc39a14. A–L, mice of indicated genotypes were euthanized at 6 weeks of age. Absolute amounts of metals in blood, brain, and liver were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (for brain and liver, n = 13 WT, 9 males and 4 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/+); 6 Slc39a14 heterozygous, 3 males and 3 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/−); 7 Slc39a14 single knockout, 4 males and 3 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14−/−); 6 Slc30a10 single knockout, all males (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14+/+); and 4 Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout, 3 males and 1 female (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14−/−); for blood, animal numbers were the same, except that two fewer male mice in the WT and Slc30a10 single knockout groups were analyzed; *, p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc test, with a, b, c, and d indicating differences in comparison with WT, Slc39a14 single, Slc30a10 single, or Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts, respectively; horizontal lines indicate mean; errors bars indicate ± S.E.).

In polarized hepatic cells, SLC39A14 localizes to the basolateral aspect, whereas SLC30A10 localizes to the canalicular domain

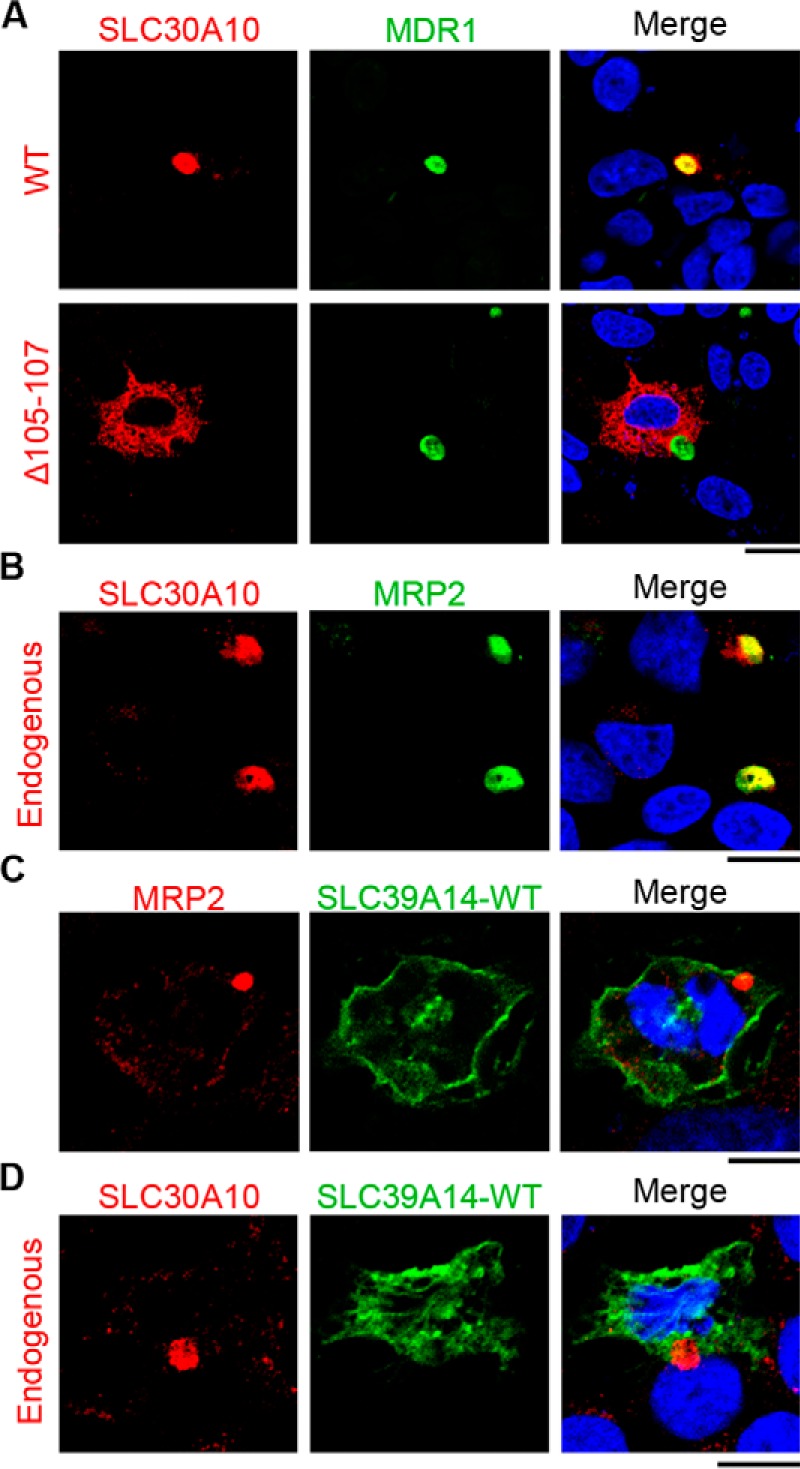

The tissue metal analyses provided experimental data consistent with the model that SLC39A14 imports manganese into hepatocytes, which is then excreted by SLC30A10 (Fig. 1). Hepatocytes are polarized cells that usually import metals and other solutes from their basolateral aspect, which interfaces with blood in the portal circulation (Fig. 1). Subsequently, intrahepatic metals are transported through the canalicular/apical domain into bile for excretion (Fig. 1). Thus, the above model predicts that SLC39A14 must localize to the basolateral aspect of hepatocytes, and SLC30A10 must localize to the apical/canalicular domain (Fig. 1). Given the clarity of the data from the double knockout, we felt it was important to test this prediction before working on the thyroid. For these assays, we used polarized HepG2 cells. SLC30A10WT overlapped with the canalicular marker MDR1 (Fig. 4A). As control, we verified that the disease-causing mutant, SLC30A10Δ105–107, failed to traffic to the cell surface and, instead, exhibited a reticular intracellular localization suggestive of retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 4A), consistent with our prior results in other cell types (23). It was important to detect localization of endogenous SLC30A10 as well. For this, we generated a custom antibody against the C terminus of the human protein and observed that endogenous SLC30A10 overlapped with another canalicular marker, MRP2 (Fig. 4B). Thus, SLC30A10 localizes to the canalicular domain of polarized hepatic cells. SLC39A14WT was also targeted to the plasma membrane, but it did not overlap with either the canalicular marker MRP2 or endogenous SLC30A10 (Fig. 4, C and D), implying that SLC39A14 localized to the basolateral domain. This observation was consistent with a prior report that localized SLC39A14 to the basolateral aspect of hepatocytes in rat liver sections (40). Thus, SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 localize to the basolateral and apical domains of polarized hepatic cells, respectively. Put together, results of Figs. 3 and 4 suggest that SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 act synergistically to mediate hepatic manganese homeostasis and detoxification.

Figure 4.

Localization of SLC39A14 and SLC30A10 in polarized hepatocytes. A, polarized HepG2 cells stably expressing the canalicular marker MDR1-GFP were transfected with FLAG-tagged SLC30A10WT or SLC30A10Δ105–107 and imaged to detect FLAG, GFP, and nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 5 μm. B, polarized HepG2 cells were stained to detect endogenous SLC30A10, the canalicular marker MRP2, and nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 5 μm. C and D, polarized HepG2 cells were transfected with GFP-SLC39A14WT and imaged to detect nuclei (blue), GFP, and the canalicular marker MRP2 or endogenous SLC30A10. Scale bars = 5 μm.

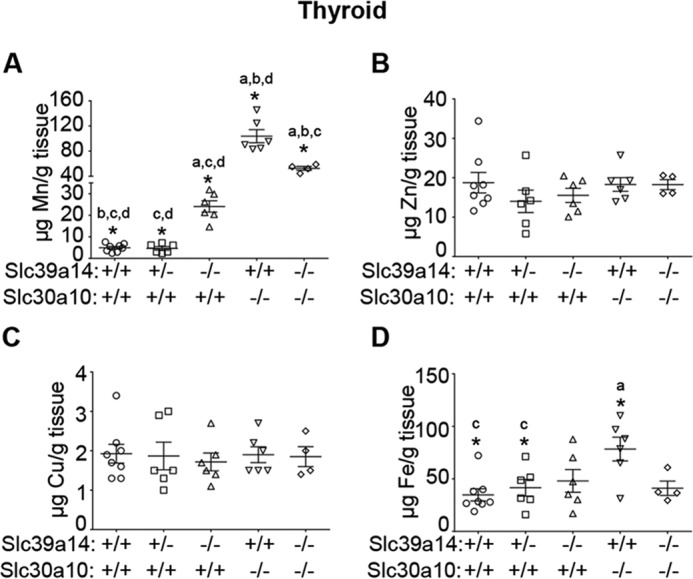

Slc39a14 single knockouts and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts are euthyroid

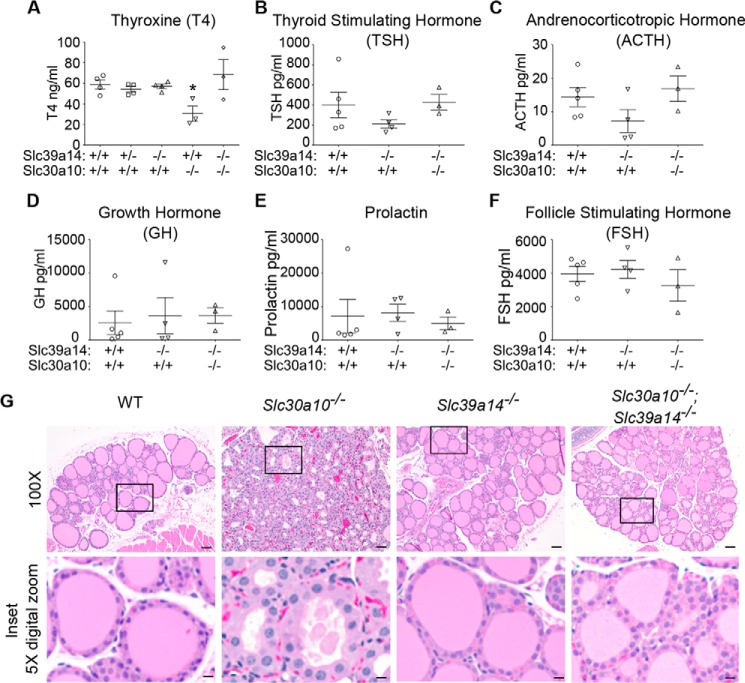

Having observed that depletion of Slc39a14 rescued elevated liver manganese levels in Slc30a10−/− mice, we sought to determine whether loss of Slc39a14 also rescued the thyroid dysfunction seen in mice lacking Slc30a10. Consistent with our recent report (22), thyroid manganese levels of Slc30a10 single knockouts were substantially (∼20-fold) higher than those of wild types (Fig. 5A). Importantly, although manganese levels in the thyroid of Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts were also greater than those of wild types, these levels were significantly lower than those of Slc30a10 single knockouts (∼75% lower for Slc39a14 single and ∼50% lower for double knockouts) (Fig. 5A). There was a minor increase in iron levels in Slc30a10 single knockouts (only ∼1-fold; this was likely secondary to alterations in manganese) and no genotype-specific changes in the levels of copper or zinc (Fig. 5, B–D). Put together, compared with Slc30a10 single knockouts, blood and brain manganese levels of Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts were higher (Fig. 3, A and B), whereas thyroid manganese levels were lower (Fig. 5A). In other words, there was a specific decrease in thyroid manganese levels in the double knockout mice, implying that these animals could be used to test the hypothesis that direct manganese toxicity in the thyroid induced hypothyroidism in Slc30a10 single knockouts. We included Slc39a14 single knockouts in the analyses of thyroid function as well because blood, brain, and thyroid manganese levels of these animals were higher than those of wild types but lower than those of Slc30a10 single or Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts (Figs. 3, A and B, and 5A). The prediction was that if a reduction in thyroid manganese protected the double knockouts against the onset of hypothyroidism, then the Slc39a14 single knockouts should also be protected. Serum thyroxine levels of Slc30a10 single knockouts were ∼50% lower than those of wild-type controls (Fig. 6A), consistent with our previous report (22). In contrast, serum thyroxine levels of Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout strains were comparable with those of wild types (Fig. 6A). Moreover, serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone as well as other anterior pituitary hormones tested were comparable between wild types and Slc39a14 single or Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout strains (Fig. 6, B–F). Finally, histological analyses confirmed that, consistent with our previous report (22), in the thyroid of Slc30a10 single knockouts, there was evidence of a decrease in colloid and diffuse hypertrophy of follicular cells (Fig. 6G). These changes were not detected in wild-type, Slc39a14 single, or Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout mice (Fig. 6G). Thus, although Slc30a10 single knockouts suffer from hypothyroidism, Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts do not. Overall, results of the metal and hormone measurement assays (Figs. 3, 5, and 6) put together indicate that direct manganese toxicity in the thyroid gland induces the hypothyroidism phenotype of Slc30a10 single knockout mice.

Figure 5.

Measurement of metal levels in the thyroid gland. A–D, absolute metal levels in the thyroid of 6-week-old mice of indicated genotypes were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (n = 8 WT, 6 males and 2 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/+); 6 Slc39a14 heterozygous, 2 males and 4 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/−); 6 Slc39a14 single knockout, 3 males and 3 females (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14−/−); 6 Slc30a10 single knockout, all males (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14+/+); and 4 Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout, 3 males and 1 female (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14−/−); *, p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc test, with a, b, c, and d indicating differences in comparison with WT, Slc39a14 single, Slc30a10 single, or Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts, respectively; horizontal lines indicate mean; errors bars indicate ± S.E.).

Figure 6.

Mice lacking Slc39a14 are euthyroid. A, thyroxine levels were measured in serum samples collected from male 6-week-old mice of indicated genotypes. Only males were used because the hypothyroidism phenotype is more severe in male Slc30a10 single knockouts (n = 4 WT (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/+); 4 Slc39a14 heterozygous (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/−); 4 Slc39a14 single knockout (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14−/−); 3 Slc30a10 single knockout (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14+/+); and 3 Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14−/−); *, p < 0.05 for the difference between WT and other groups using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test; horizontal lines indicate mean; errors bars indicate ± S.E.). B–F, serum levels of anterior pituitary hormones were measured from samples collected from male 6-week-old mice (n = 5 WT (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14+/+); 4 Slc39a14 single knockout (Slc30a10+/+/Slc39a14−/−); and 3 Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockout (Slc30a10−/−/Slc39a14−/−); there were no differences between WT and other groups using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test; horizontal lines indicate mean; errors bars indicate ± S.E.). G, sections of thyroid were generated from 6-week-old mice of indicated genotypes, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and imaged. Scale bars = 100 μm (full frame) and 20 μm (inset).

Interestingly, the thyroid of the double knockouts showed some follicle-to-follicle variability in height of the epithelium and density of colloid, which was not evident in Slc39a14 single knockout or wild-type mice (Fig. 6G). Notably, thyroid manganese levels of the double knockouts were higher than those of Slc39a14 single knockouts but lower than those of Slc30a10 single knockouts (Fig. 5A). It may be that the amount of manganese that accumulated in the thyroid of the double knockouts was sufficient to induce some tissue alterations but not to produce hypothyroidism.

Intrathyroid thyroxine production is deficient in Slc30a10 single knockouts

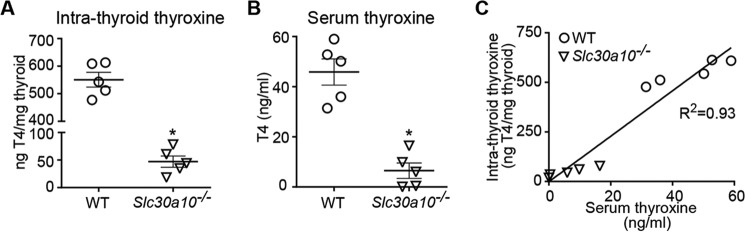

Thyroxine is produced in the thyroid gland by iodination and subsequent proteolytic cleavage of thyroglobulin protein (35, 36). Intrathyroid thyroxine is then secreted into the blood (35, 36). Inhibition of thyroxine production was a possible mechanism by which elevated thyroid manganese could induce hypothyroidism in Slc30a10−/− mice. To test this hypothesis, we extracted thyroxine from thyroid glands of wild-type or Slc30a10 single knockouts and compared levels. Importantly, compared with wild types, levels of intrathyroid thyroxine of Slc30a10 single knockout mice were significantly lower (Fig. 7A). In the same animals, serum thyroxine levels of Slc30a10 single knockouts were also significantly lower (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, on a per-animal basis, there was a strong correlation between intrathyroid and serum thyroxine levels (Fig. 7C). That is, mice with lower intrathyroid thyroxine also had lower serum thyroxine (Fig. 7C). In sum, our results indicate that, in Slc30a10 single knockouts, manganese toxicity in the thyroid inhibits thyroxine production, which decreases serum thyroxine levels and induces hypothyroidism.

Figure 7.

Intrathyroid thyroxine levels are lower in Slc30a10 single knockouts. A and B, thyroxine levels were measured in samples of the thyroid (A) or serum (B) obtained from 6-week-old male WT or Slc30a10 single knockout mice (n = 5 for each genotype; *, p < 0.05 by t test; horizontal lines indicate mean; errors bars indicate ± S.E.). C, correlation between levels of serum and intrathyroid thyroxine from A and B above.

Discussion

Our results imply that hypothyroidism in Slc30a10 single knockouts occurs because of direct manganese-dependent injury to the thyroid gland and not as a consequence of manganese-induced damage to another organ, such as the brain. The mechanism is a profound deficiency in intrathyroid thyroxine production. Further support for the role of manganese toxicity in inducing hypothyroidism in Slc30a10 knockouts comes from our previously published finding that a low-manganese diet reduced body manganese levels and rescued thyroid dysfunction (22). Our work sets the stage for future studies to determine the precise step in thyroxine biosynthesis that is impacted by manganese. As an example, manganese may affect the function of transporters required for iodide import. Indeed, a study in rodents demonstrated that there was a reduction in the uptake of iodide into the thyroid of rats treated with manganese (42). Alternatively, elevated cellular manganese impacts intracellular trafficking (43–46). Therefore, during manganese toxicity, trafficking of thyroglobulin between thyroid epithelial cells and the follicular lumen, which is required for thyroxine production (35, 36), may be compromised. Additionally, coupling of iodine to thyroglobulin is dependent on activity of the heme-containing enzyme thyroid peroxidase (35, 36, 47), and mismetallation of this peroxidase may inhibit thyroxine production.

Slc39a14 single knockouts and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts were euthyroid, although their thyroid manganese levels were greater than those of wild types. Therefore, a related implication of our findings is that manganese levels in the thyroid need to increase beyond a threshold before thyroid dysfunction becomes evident. The euthyroid status of mice lacking Slc39a14 suggests that these animals may be useful to study the neurotoxic effects of manganese in the absence of thyroid dysfunction.

The discovery that Slc30a10 knockout mice develop hypothyroidism suggests that thyroid dysfunction may be an unappreciated facet of manganese toxicity that contributes to the neurological symptoms evident in the disease. Literature on the relationship between thyroid biology and manganese toxicity is quite limited, but a few prior studies support this idea. In humans, an association between occupational exposure to elevated manganese and changes in serum thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels was reported in one study (48). Levels of plasma manganese were elevated in individuals with goiter in another study (49). In rodents, administration of manganese was reported to reduce serum levels of thyroxine or induce goiter (42, 50, 51). Thus, there is precedent for our discovery of manganese-induced thyroid defects in Slc30a10 knockout mice. Moreover, thyroid hormone plays a major role in neural development, and hypothyroidism in early life may produce defects in cognition, learning, attentional, and intellectual capabilities (35, 36, 52). Interestingly, similar neurological deficits are reported in human and rodent studies of early-life manganese exposure (5–17). Thus, it is also possible that thyroid dysfunction may enhance the neurological deficits observed during manganese toxicity. Mice lacking Slc30a10 and/or Slc39a14 may be useful models to study the relationship between thyroid function and manganese-induced neurotoxicity. A positive result in rodent assays may provide justification for conducting well controlled epidemiological studies to elucidate the relationships between thyroid function, manganese exposure, and neurological deficits in humans and, subsequently, for performance of clinical trials to determine whether thyroxine supplementation protects.

Compared with wild-type controls, liver manganese levels of Slc30a10 single knockouts were elevated whereas those of Slc39a14 single and Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts were not. These results are consistent with findings in human patients harboring loss-of-function mutations in SLC39A14 or SLC30A10 and with recent publications on Slc30a10 and Slc39a14 single knockouts (18–22, 25–27). The available evidence indicates that SLC39A14 is obligatorily required for the influx of manganese from blood into hepatocytes, and SLC30A10 is obligatorily required for the efflux of manganese from hepatocytes to bile (Fig. 1).

Other transporters in the SLC30 family mediate zinc efflux (53–55), and SLC30A10 was initially thought to be a zinc transporter (56). However, recent work by us and others shows that SLC30A10 primarily mediates manganese but not zinc efflux (20, 22–24, 34, 38, 39, 57). Important pieces of evidence that led to the above conclusion came from our studies showing that, in cell culture, overexpression of SLC30A10 reduced intracellular manganese levels and protected against manganese toxicity but did not impact zinc levels or toxicity (23, 24); in C. elegans, overexpression of SLC30A10 protected against manganese but not zinc toxicity (23, 38), and in Slc30a10−/− mice, levels of tissue manganese, but not zinc, were elevated (22). The lack of elevation in tissue zinc levels in the current cohort of Slc30a10−/− mice is consistent with our prior findings. We also reported that the putative metal-binding site within the transmembrane domain of SLC30A10 differed from that of related zinc transporters (24); such differences may underlie the transport specificity of SLC30A10.

Unlike SLC30A10, prior studies indicate that, in cell culture, SLC39A14 has the capacity to transport zinc, iron, and cadmium in addition to manganese (28–33). However, we discovered that, in HeLa cells, SLC39A14 robustly transported manganese but not zinc or iron. Cell type-specific differences in the capability of SLC39A14 to transport metals other than manganese may depend on the differential expression of metal transporters in different cells. Importantly, in human patients with mutations in SLC39A14, only manganese levels were elevated (25). Additionally, recent studies on Slc39a14−/− mice (26, 27) and this work revealed that knockouts primarily accumulated manganese. Thus, at the organism level, the primary function of SLC39A14 appears to be to mediate transport and regulate homeostasis of manganese.

Interestingly, brain manganese levels of Slc39a14 single knockouts were ∼15-fold greater than those of wild types, suggesting that Slc39a14 is not required for the influx of manganese into neuronal cells. So far, the identity of transporters that specifically mediate the influx of manganese into neuronal and glial cells is unclear. Interestingly, the double knockouts had higher brain manganese than Slc30a10 single knockouts. It is possible that depletion of both Slc30a10 and Slc39a14 has a more profound effect on increasing the body burden of manganese than depletion of either transporter by itself. This idea is consistent with the observation that blood manganese levels of the double knockouts were greater than those of either single knockout. It is also possible that the activity of Slc30a10 in the brain plays a role in reducing manganese levels in the central nervous system. Overall, clinical and animal studies on SLC30A10 and SLC39A14 (18–22, 25–27), as well as on another manganese transporter named SLC39A8 (also called ZIP8; loss of function of SLC39A8 induces manganese deficiency (58–60)), suggest that there are important differences in the mechanisms by which different organs regulate manganese homeostasis. Careful characterization of organ-specific knockouts of these transporters is essential to better understand the mode of regulation of manganese homeostasis at the whole-animal level.

In conclusion, activities of Slc39a14 and Slc30a10 are required for the excretion of manganese by the liver, and hypothyroidism in Slc30a10 single knockout mice occurs because of manganese-induced inhibition in thyroxine production.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

All experiments with mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Austin. We recently described the generation of full-body, constitutive Slc30a10 single knockouts (22). Full-body, constitutive Slc39a14 knockout mice in which coding exons 1–3 of Slc39a14 are deleted have been described previously (41). Cryopreserved sperm for Slc39a14+/− males (B6;129S5-Slc39a14tm1Lex/Mmucd) was obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center, a National Institutes of Health–funded strain repository, and was donated to the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center by Lexicon Genetics Inc. The strain was recovered by in vitro fertilization (61) at the Mouse Genetic Engineering Facility of the University of Texas at Austin. Heterozygous Slc39a14+/− animals were crossed to obtain Slc39a14−/− single knockouts. To generate Slc30a10/Slc39a14 double knockouts, animals heterozygous for knockout of Slc30a10 or Slc39a14 were crossed to obtain mice that were heterozygous for knockout of both genes. These double heterozygous animals were then intercrossed to obtain the double knockout. Mice were housed in the specific pathogen-free facility of the University of Texas at Austin in a room maintained at ∼21 °C with a 12-h light-dark cycle (lights on between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m.). Animals were weaned at 21 days of age. After weaning, three to four littermates of the same sex were kept per cage. Animals had free access to food and water and were fed PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, which contains ∼84 μg of manganese/g of chow.

Genotyping

Animals were genotyped by performing PCR from genomic DNA extracted from tail snips. Primers and PCR conditions used to amplify Slc30a10 alleles were identical to those described by us recently (22). Primers used to amplify Slc39a14 alleles were as follows: for the wild-type allele, 5′ TCA TGG ACC GCT ATG GAA AG 3′ and 5′ GTG TCC AGC GGT ATC AAC AGA GAG 3′; for the knockout allele, 5′ GCA GCG CAT CGC CTT CTA TC 3′ and 5′ TGC CTG GCA CAT AGA ATG C 3′. PCR was performed using a touch-down cycling protocol; for the first cycle, annealing was at 65 °C, for the next nine cycles, the annealing temperature was reduced by 1 °C per cycle, and for the subsequent 30 cycles, annealing was at 55 °C. In each cycle, denaturation was at 94 °C for 15 s, and elongation was at 72 °C for 40 s. This PCR produced one band of ∼160 base pairs for the wild-type and one band of ∼470 base pairs for the knockout allele. Techniques and reagents used to extract genomic DNA and perform PCR were described previously (22).

Reverse transcription PCR

Mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide. Tissues were isolated and processed as described previously (22, 23). PCR primers and conditions used to amplify Slc30a10 gene product were also described previously (22). Primers used to amplify the Slc39a14 gene product were as follows: 5′ AAG TCC CTG CTC GAC CAC 3′ and 5′ CTG GGA ATC CAG CTG CTG 3′. PCR conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

Mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide. Further processing was performed as described previously (22, 23). Primers for amplifying Slc30a10 and 18S gene products were described previously (22) and were as described above for the Slc39a14 gene product. Transcript levels were quantified using the ΔΔCT method; 18S was the internal control (62).

Metal and serum hormone measurements and histology analyses using mouse samples

These were performed exactly as described by us recently (22).

Intrathyroid thyroxine measurements

Thyroid was harvested from mice euthanized using carbon dioxide, as described by us recently (22). After this, per animal, one lobe of the thyroid was resuspended in 500 μl of homogenizing buffer (50 mm each of sodium barbital (pH 8.6), sodium azide, and EDTA). Samples were sonicated (2 pulses of 20 s each) and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant, which was the homogenate, was used for digestion and extraction of thyroxine. For this, 150 μl of digestion buffer (100 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.8), 0.625 mg/ml Pronase, and 2.45 mm 2-thiouracil) was added to 150 μl of homogenate. To this mixture, 15 μl of toluene was added. The solution was vortexed and then incubated for 48 h in a water bath kept at 37 °C. Finally, samples were boiled for 2 min to inactivate the protease, and thyroxine levels were measured using the AccuDiag T4 ELISA kit (Diagnostic Automation/Cortex Diagnostics, Inc., Woodland Hills, CA), as described by us recently for serum samples (22). To ensure that readings were within the standard curve, samples were diluted 2- to 4-fold using toluene-supplemented digestion buffer that lacked Pronase. ELISA readings (in ng/ml) were used to calculate total thyroxine per thyroid lobe (in nanograms), which was divided by the weight of the thyroid lobe to obtain thyroxine levels in units of nanograms of thyroxine per milligram of thyroid.

Cell culture assays: Plasmids and antibodies

We previously described FLAG-SLC30A10WT, FLAG-SLC30A10Δ105–107, and GFP-Rab5 (used as a control) constructs (23, 24). To generate a plasmid coding for SLC39A14WT, we produced complementary DNA from RNA extracted from HepG2 cells, amplified SLC39A14 by using 5′ GTC GGT ACC ATG AAG CTG CTG CTG CTG CAC 3′ and 5′-CGC GGA TCC CCC AAT CTG GAT CTG TCC TGA ATA C 3′ primers, cleaved the PCR product using KpnI and BamHI enzymes, and ligated the cleaved product into pEGFP-N3 vector. To generate a custom antibody against SLC30A10, we purified the C-terminal domain of human SLC30A10 (residues 308–485) along with an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase tag. Protein purification was performed as described by us previously (45, 46). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against this immunogen was generated using the services of Covance Biologicals. Antibodies against the bile canalicular marker MRP2, FLAG epitope, and tubulin have been described by us previously (23, 24, 63). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against GFP was from Clontech.

Cell culture assays: HeLa cells

Detailed methodologies for growth, transfection, treatment with manganese (as manganese chloride), viability assessment using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide reagent, intracellular metal measurements, immunoblot analyses, and immunofluorescence microscopy are provided in Refs. 23, 24, and 64. These techniques were performed exactly as described previously (23, 24, 64).

Cell culture assays: HepG2 cells

Wild-type HepG2 cells or those stably overexpressing the canalicular marker MDR1-GFP were grown, polarized, transfected, and imaged as described previously (63, 65).

Statistical analyses

Animal numbers are provided in the figure legends. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way ANOVA2 and appropriate post hoc tests. Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student's t test. The Prism 6 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) was used. p < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Asterisks in graphs denote statistically significant differences.

Author contributions

C. L., S. H., T. J., W. S., E. V. P., and B. K. D. performed experiments. C. L., R. S. P., A. C. G., D. R. S., and S. M. interpreted data. C. L. and S. M. prepared figures. S. M. conceived the project and wrote the paper with contributions from C. L., R. S. P., A. C. G., M. A., and D. R. S. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Veerle Darras (KU Leuven, Belgium) for providing the protocol used for extracting thyroxine from thyroid glands.

This work was supported by NIEHS, National Institutes of Health Grants R01-ES024812 and R00-ES020844 (to S. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Aschner M., Erikson K. M., Herrero Hernández E., Hernández E. H., and Tjalkens R. (2009) Manganese and its role in Parkinson's disease: from transport to neuropathology. Neuromolecular Med. 11, 252–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butterworth R. F. (2013) Parkinsonism in cirrhosis: pathogenesis and current therapeutic options. Metab. Brain Dis. 28, 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olanow C. W. (2004) Manganese-induced parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1012, 209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perl D. P., and Olanow C. W. (2007) The neuropathology of manganese-induced Parkinsonism. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66, 675–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaudin S. A., Nisam S., and Smith D. R. (2013) Early life versus lifelong oral manganese exposure differently impairs skilled forelimb performance in adult rats. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 38, 36–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beaudin S. A., Strupp B. J., Strawderman M., and Smith D. R. (2017) Early postnatal manganese exposure causes lasting impairment of selective and focused attention and arousal regulation in adult rats. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 230–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhang S. Y., Cho S. C., Kim J. W., Hong Y. C., Shin M. S., Yoo H. J., Cho I. H., Kim Y., and Kim B. N. (2013) Relationship between blood manganese levels and children's attention, cognition, behavior, and academic performance: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 126, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bouchard M., Laforest F., Vandelac L., Bellinger D., and Mergler D. (2007) Hair manganese and hyperactive behaviors: pilot study of school-age children exposed through tap water. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 122–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bouchard M. F., Sauvé S., Barbeau B., Legrand M., Brodeur M. È., Bouffard T., Limoges E., Bellinger D. C., and Mergler D. (2011) Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 138–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Claus Henn B., Ettinger A. S., Schwartz J., Téllez-Rojo M. M., Lamadrid-Figueroa H., Hernández-Avila M., Schnaas L., Amarasiriwardena C., Bellinger D. C., Hu H., and Wright R. O. (2010) Early postnatal blood manganese levels and children's neurodevelopment. Epidemiology 21, 433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kern C. H., Stanwood G. D., and Smith D. R. (2010) Preweaning manganese exposure causes hyperactivity, disinhibition, and spatial learning and memory deficits associated with altered dopamine receptor and transporter levels. Synapse 64, 363–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan K., Factor-Litvak P., Wasserman G. A., Liu X., Ahmed E., Parvez F., Slavkovich V., Levy D., Mey J., van Geen A., and Graziano J. H. (2011) Manganese exposure from drinking water and children's classroom behavior in Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 1501–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan K., Wasserman G. A., Liu X., Ahmed E., Parvez F., Slavkovich V., Levy D., Mey J., van Geen A., Graziano J. H., and Factor-Litvak P. (2012) Manganese exposure from drinking water and children's academic achievement. Neurotoxicology 33, 91–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lucchini R. G., Guazzetti S., Zoni S., Donna F., Peter S., Zacco A., Salmistraro M., Bontempi E., Zimmerman N. J., and Smith D. R. (2012) Tremor, olfactory and motor changes in Italian adolescents exposed to historical ferro-manganese emission. Neurotoxicology 33, 687–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oulhote Y., Mergler D., Barbeau B., Bellinger D. C., Bouffard T., Brodeur M. È., Saint-Amour D., Legrand M., Sauvé S., and Bouchard M. F. (2014) Neurobehavioral function in school-age children exposed to manganese in drinking water. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 1343–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riojas-Rodríguez H., Solís-Vivanco R., Schilmann A., Montes S., Rodríguez S., Ríos C., and Rodríguez-Agudelo Y. (2010) Intellectual function in Mexican children living in a mining area and environmentally exposed to manganese. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1465–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wasserman G. A., Liu X., Parvez F., Ahsan H., Levy D., Factor-Litvak P., Kline J., van Geen A., Slavkovich V., LoIacono N. J., Cheng Z., Zheng Y., and Graziano J. H. (2006) Water manganese exposure and children's intellectual function in Araihazar, Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 124–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lechpammer M., Clegg M. S., Muzar Z., Huebner P. A., Jin L. W., and Gospe S. M. Jr. (2014) Pathology of inherited manganese transporter deficiency. Ann. Neurol. 75, 608–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quadri M., Federico A., Zhao T., Breedveld G. J., Battisti C., Delnooz C., Severijnen L. A., Di Toro Mammarella L., Mignarri A., Monti L., Sanna A., Lu P., Punzo F., Cossu G., Willemsen R., et al. (2012) Mutations in SLC30A10 cause parkinsonism and dystonia with hypermanganesemia, polycythemia, and chronic liver disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 467–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tuschl K., Clayton P. T., Gospe S. M. Jr., Gulab S., Ibrahim S., Singhi P., Aulakh R., Ribeiro R. T., Barsottini O. G., Zaki M. S., Del Rosario M. L., Dyack S., Price V., Rideout A., Gordon K., et al. (2012) Syndrome of hepatic cirrhosis, dystonia, polycythemia, and hypermanganesemia caused by mutations in SLC30A10, a manganese transporter in man. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 457–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tuschl K., Mills P. B., Parsons H., Malone M., Fowler D., Bitner-Glindzicz M., and Clayton P. T. (2008) Hepatic cirrhosis, dystonia, polycythaemia and hypermanganesaemia: a new metabolic disorder. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 31, 151–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hutchens S., Liu C., Jursa T., Shawlot W., Chaffee B. K., Yin W., Gore A. C., Aschner M., Smith D. R., and Mukhopadhyay S. (2017) Deficiency in the manganese efflux transporter SLC30A10 induces severe hypothyroidism in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 9760–9773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leyva-Illades D., Chen P., Zogzas C. E., Hutchens S., Mercado J. M., Swaim C. D., Morrisett R. A., Bowman A. B., Aschner M., and Mukhopadhyay S. (2014) SLC30A10 is a cell surface-localized manganese efflux transporter, and parkinsonism-causing mutations block its intracellular trafficking and efflux activity. J. Neurosci. 34, 14079–14095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zogzas C. E., Aschner M., and Mukhopadhyay S. (2016) Structural elements in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the metal transporter SLC30A10 are required for its manganese efflux activity. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 15940–15957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tuschl K., Meyer E., Valdivia L. E., Zhao N., Dadswell C., Abdul-Sada A., Hung C. Y., Simpson M. A., Chong W. K., Jacques T. S., Woltjer R. L., Eaton S., Gregory A., Sanford L., Kara E., et al. (2016) Mutations in SLC39A14 disrupt manganese homeostasis and cause childhood-onset parkinsonism-dystonia. Nat. Commun. 7, 11601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aydemir T. B., Kim M. H., Kim J., Colon-Perez L. M., Banan G., Mareci T. H., Febo M., and Cousins R. J. (2017) Metal transporter Zip14 (Slc39a14) deletion in mice increases manganese deposition and produces neurotoxic signatures and diminished motor activity. J. Neurosci. 37, 5996–6006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xin Y., Gao H., Wang J., Qiang Y., Imam M. U., Li Y., Wang J., Zhang R., Zhang H., Yu Y., Wang H., Luo H., Shi C., Xu Y., Hojyo S., et al. (2017) Manganese transporter Slc39a14 deficiency revealed its key role in maintaining manganese homeostasis in mice. Cell Discovery 3, 17025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Girijashanker K., He L., Soleimani M., Reed J. M., Li H., Liu Z., Wang B., Dalton T. P., and Nebert D. W. (2008) Slc39a14 gene encodes ZIP14, a metal/bicarbonate symporter: similarities to the ZIP8 transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1413–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenkitkasemwong S., Wang C. Y., Mackenzie B., and Knutson M. D. (2012) Physiologic implications of metal-ion transport by ZIP14 and ZIP8. Biometals 25, 643–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liuzzi J. P., Aydemir F., Nam H., Knutson M. D., and Cousins R. J. (2006) Zip14 (Slc39a14) mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake into cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liuzzi J. P., Lichten L. A., Rivera S., Blanchard R. K., Aydemir T. B., Knutson M. D., Ganz T., and Cousins R. J. (2005) Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to the hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6843–6848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pinilla-Tenas J. J., Sparkman B. K., Shawki A., Illing A. C., Mitchell C. J., Zhao N., Liuzzi J. P., Cousins R. J., Knutson M. D., and Mackenzie B. (2011) Zip14 is a complex broad-scope metal-ion transporter whose functional properties support roles in the cellular uptake of zinc and nontransferrin-bound iron. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C862–C871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeong J., and Eide D. J. (2013) The SLC39 family of zinc transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 612–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mukhopadhyay S. (2017) Familial manganese-induced neurotoxicity because of mutations in SLC30A10 or SLC39A14. Neurotoxicology 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hall J. E. (2016) in Textbook of Medical Physiology, pp. 951–963, Elsevier, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 36. Braveman L. E., and Cooper D. S. (eds) (2013) Werner & Ingbar's The thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text, 10th Ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taylor K. M., Morgan H. E., Johnson A., and Nicholson R. I. (2005) Structure-function analysis of a novel member of the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters, ZIP14. FEBS Lett. 579, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen P., Bowman A. B., Mukhopadhyay S., and Aschner M. (2015) SLC30A10: a novel manganese transporter. Worm 4, e1042648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishito Y., Tsuji N., Fujishiro H., Takeda T. A., Yamazaki T., Teranishi F., Okazaki F., Matsunaga A., Tuschl K., Rao R., Kono S., Miyajima H., Narita H., Himeno S., and Kambe T. (2016) Direct comparison of manganese detoxification/efflux proteins and molecular characterization of ZnT10 protein as a manganese transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 14773–14787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nam H., Wang C. Y., Zhang L., Zhang W., Hojyo S., Fukada T., and Knutson M. D. (2013) ZIP14 and DMT1 in the liver, pancreas, and heart are differentially regulated by iron deficiency and overload: implications for tissue iron uptake in iron-related disorders. Haematologica 98, 1049–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tang T., Li L., Tang J., Li Y., Lin W. Y., Martin F., Grant D., Solloway M., Parker L., Ye W., Forrest W., Ghilardi N., Oravecz T., Platt K. A., Rice D. S., et al. (2010) A mouse knockout library for secreted and transmembrane proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 749–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buthieau A. M., and Autissier N. (1977) The effect of Mn2+ on thyroid iodine metabolism in rats. C R Seances Soc. Biol. Fil. 171, 1024–1028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mukhopadhyay S., Bachert C., Smith D. R., and Linstedt A. D. (2010) Manganese-induced trafficking and turnover of the cis-Golgi glycoprotein GPP130. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1282–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mukhopadhyay S., and Linstedt A. D. (2011) Identification of a gain-of-function mutation in a Golgi P-type ATPase that enhances Mn2+ efflux and protects against toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 858–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mukhopadhyay S., and Linstedt A. D. (2012) Manganese blocks intracellular trafficking of Shiga toxin and protects against Shiga toxicosis. Science 335, 332–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mukhopadhyay S., Redler B., and Linstedt A. D. (2013) Shiga toxin-binding site for host cell receptor GPP130 reveals unexpected divergence in toxin-trafficking mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 2311–2318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Le S. N., Porebski B. T., McCoey J., Fodor J., Riley B., Godlewska M., Góra M., Czarnocka B., Banga J. P., Hoke D. E., Kass I., and Buckle A. M. (2015) Modelling of thyroid peroxidase reveals insights into its enzyme function and autoantigenicity. PLoS ONE 10, e0142615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Misiewicz A., Radwan K., Karmoliński M., Dziewit T., and Matysek A. (1993) Effect of occupational environment containing manganese on thyroid function. Endokrynol. Pol. 44, 57–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Giray B., Arnaud J., Sayek I., Favier A., and Hincal F. (2010) Trace elements status in multinodular goiter. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 24, 106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Buthieau A. M., and Autissier N. (1983) Effects of manganese ions on thyroid function in rat. Arch. Toxicol. 54, 243–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kawada J., Nishida M., Yoshimura Y., and Yamashita K. (1985) Manganese ion as a goitrogen in the female mouse. Endocrinol. Jpn. 32, 635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zoeller R. T., Tan S. W., and Tyl R. W. (2007) General background on the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 37, 11–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huang L., and Tepaamorndech S. (2013) The SLC30 family of zinc transporters: a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 548–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kambe T., Tsuji T., Hashimoto A., and Itsumura N. (2015) The physiological, biochemical, and molecular roles of zinc transporters in zinc homeostasis and metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 95, 749–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kolaj-Robin O., Russell D., Hayes K. A., Pembroke J. T., and Soulimane T. (2015) Cation diffusion facilitator family: structure and function. FEBS Lett. 589, 1283–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bosomworth H. J., Thornton J. K., Coneyworth L. J., Ford D., and Valentine R. A. (2012) Efflux function, tissue-specific expression and intracellular trafficking of the Zn transporter ZnT10 indicate roles in adult Zn homeostasis. Metallomics 4, 771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xia Z., Wei J., Li Y., Wang J., Li W., Wang K., Hong X., Zhao L., Chen C., Min J., and Wang F. (2017) Zebrafish slc30a10 deficiency revealed a novel compensatory mechanism of Atp2c1 in maintaining manganese homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boycott K. M., Beaulieu C. L., Kernohan K. D., Gebril O. H., Mhanni A., Chudley A. E., Redl D., Qin W., Hampson S., Küry S., Tetreault M., Puffenberger E. G., Scott J. N., Bezieau S., Reis A., et al. (2015) Autosomal-recessive intellectual disability with cerebellar atrophy syndrome caused by mutation of the manganese and zinc transporter gene SLC39A8. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 886–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lin W., Vann D. R., Doulias P. T., Wang T., Landesberg G., Li X., Ricciotti E., Scalia R., He M., Hand N. J., and Rader D. J. (2017) Hepatic metal ion transporter ZIP8 regulates manganese homeostasis and manganese-dependent enzyme activity. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 2407–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Park J. H., Hogrebe M., Grüneberg M., DuChesne I., von der Heiden A. L., Reunert J., Schlingmann K. P., Boycott K. M., Beaulieu C. L., Mhanni A. A., Innes A. M., Hortnagel K., Biskup S., Gleixner E. M., Kurlemann G., et al. (2015) SLC39A8 deficiency: a disorder of manganese transport and glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 894–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeo T., and Nakagata N. (2011) Reduced glutathione enhances fertility of frozen/thawed C57BL/6 mouse sperm after exposure to methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Biol. Reprod. 85, 1066–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Livak K. J., and Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔ C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Polishchuk E. V., Concilli M., Iacobacci S., Chesi G., Pastore N., Piccolo P., Paladino S., Baldantoni D., van Ijzendoorn S. C., Chan J., Chang C. J., Amoresano A., Pane F., Pucci P., Tarallo A., et al. (2014) Wilson disease protein ATP7B utilizes lysosomal exocytosis to maintain copper homeostasis. Dev. Cell 29, 686–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Selyunin A. S., and Mukhopadhyay S. (2015) A conserved structural motif mediates retrograde trafficking of Shiga toxin types 1 and 2. Traffic 16, 1270–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chesi G., Hegde R. N., Iacobacci S., Concilli M., Parashuraman S., Festa B. P., Polishchuk E. V., Di Tullio G., Carissimo A., Montefusco S., Canetti D., Monti M., Amoresano A., Pucci P., van de Sluis B., et al. (2016) Identification of p38 MAPK and JNK as new targets for correction of Wilson disease-causing ATP7B mutants. Hepatology 63, 1842–1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]