Abstract

Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1), involved in cancer progression and chemoradiation resistance, is overexpressed in not only cancer cells but also tumor blood vessels. In this study, we investigated the potential value of amido-bridged nucleic acid (AmNA)-modified antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting YB-1 (YB-1 ASOA) as an antiangiogenic cancer therapy. YB-1 ASOA was superior to natural DNA-based ASO or locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified YB-1 ASO in both knockdown efficiency and safety, the latter assessed by liver function. YB-1 ASOA administered i.v. significantly inhibited YB-1 expression in CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells, but not in cancer cells, in the tumors. With regard to the mechanism of its antiangiogenic effects, YB-1 ASOA downregulated both Bcl-xL/VEGFR2 and Bcl-xL/Tie signal axes, which are key regulators of angiogenesis, and induced apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. In the xenograft tumor model that had low sensitivity to anti-VEGF antibody, YB-1 ASOA significantly suppressed tumor growth; not only VEGFR2 but also Tie2 expression was decreased in tumor vessels. In conclusion, YB-1/Bcl-xL/VEGFR2 and YB-1/Bcl-xL/Tie signal axes play pivotal roles in tumor angiogenesis, and YB-1 ASOA may be feasible as an antiangiogenic therapy for solid tumors.

Keywords: YB-1, ASO, tumor angiogenesis, VEGFR2, Tie

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Advances in molecular biology and biochemical engineering have led to the development of molecular target-based therapies against cancers, which are expected to be less toxic than chemotherapeutic agents. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), single-stranded, 12- to 25-residue-length nucleic acids, bind to the complementary mRNA sequences coding for target molecules and inhibit gene translation via degradation of the mRNA by endogenous RNase H activity.1, 2, 3 However, unmodified ASOs, with phosphodiester-linked structures, have limited effectiveness in vivo because they are vulnerable to endogenous nucleases. To address this problem, chemically modified ASOs incorporated by locked nucleic acids (LNAs) or amido-bridged nucleic acids (AmNAs) with phosphorothioate-linked structures have been developed to achieve higher affinity and nuclease resistance with lower toxicity.4, 5, 6

To design ASO reagents useful for treating cancer patients, it is important to select target molecules that are upregulated in cancerous tissue regions and are related to tumor survival and progression. Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1), originally identified as a member of the cold-shock protein superfamily,7, 8 is overexpressed not only in cancer cells,9, 10, 11, 12 but also in vascular endothelia in tumor tissues.13 YB-1 plays an important role in proliferation, invasion, multi-drug resistance, and malignant transformation in a variety of cancers.14, 15, 16 YB-1 may also be involved in signaling by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a critical factor for angiogenesis.17, 18, 19 However, the biological significance of YB-1 in angiogenesis in a tumor microenvironment has not been well elucidated,20, 21 because intracellular delivery of the RNAi and protein reagents has not met full success in vivo, although in vitro and ex vivo transfection of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or dominant negative YB-1 mutants inhibits YB-1 activation and decreases viabilities of cancer cells22, 23 and vascular endothelial cells.24 We hypothesize LNA- and/or AmNA-based YB-1-targeting ASOs (designated as YB-1 ASOL and YB-1 ASOA, respectively) may enable evaluation of the influence of YB-1 on angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment, including cancer cells and stromal vasculatures.

In this study, we established YB-1 ASOA as an efficient YB-1 knockdown system in vivo and demonstrated that YB-1 ASOA exhibited antiangiogenic effects on proliferating vascular endothelial cells in the tumor microenvironment, mediated by the blockade of VEGF receptor (VEGFR) and Tie receptor signaling via Bcl-xL suppression. These results not only demonstrate the feasibility of YB-1 ASOA-based tumor dormancy therapy for intractable cancers in vivo but also provide proof of principle for the significance of YB-1 signaling in tumor angiogenesis.

Results

Establishment of an ASO-Based YB-1 Knockdown System

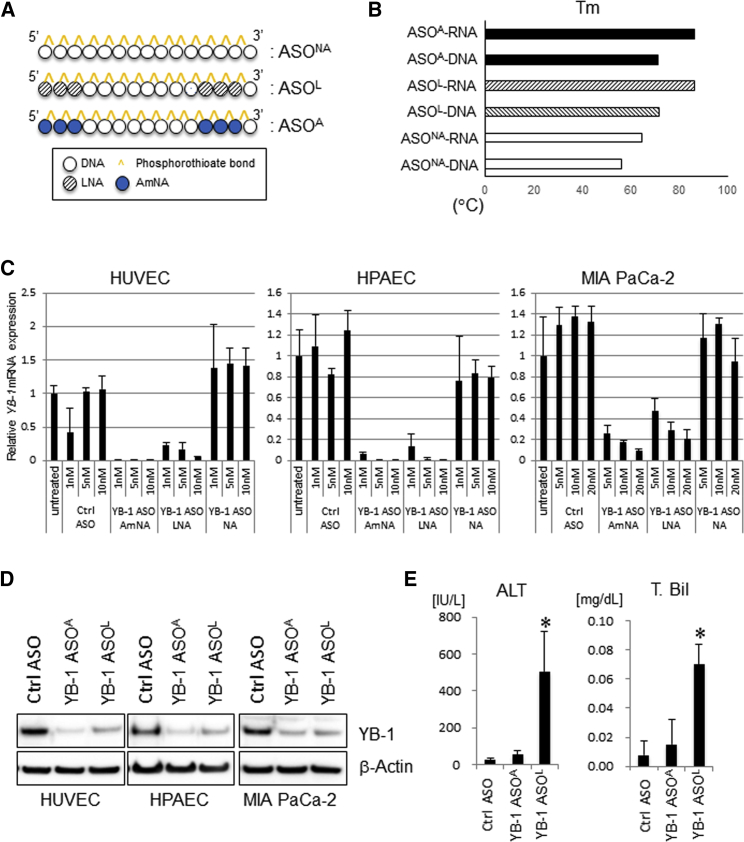

We generated a 15-mer ASO containing nucleic acids (ASONA) and chemically modified ASOs flanked by LNAs or AmNAs, with phosphorothioate-linked structures, targeting both mouse and human YBX1 mRNAs (YB-1 ASONA, YB-1 ASOL, and YB-1 ASOA, respectively) (Figure 1A; Figure S1). The sequences of ASOs were 5′-TmCT cct gca ccmC TGg-3′ for YB-1 ASOs and 5′-mCAT ttc gaa gtA mCT c-3′ for control ASO (uppercase, LNA or AmNA; lowercase, DNA; mC, 5-methylated cytosine). YB-1 ASOL and YB-1 ASOA showed superior thermal stabilities (Tm values), as an index of binding affinity to complementary RNA strands, compared to ASONA (Figure 1B). Correspondingly, knockdown efficiencies of YB-1 ASOA and YB-1 ASO were greater than that of YB-1 ASONA, at both mRNA and protein levels, in vascular endothelial and pancreatic cancer MIA PaCa-2 cells (Figures 1C and 1D). YB-1 ASOA exhibited slightly higher knockdown efficiency than YB-1 ASOL, but the difference was not significant (Figures 1C and 1D). To identify which ASO was most useful for in vivo application, we evaluated their safety potentials when systemically administered. In mice receiving YB-1 ASOL, but not YB-1 ASOA, there was elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (T. Bil), indicators of liver damage (Figure 1E), although renal function was not different between YB-1 ASOL and YB-1 ASOA (BUN, 24 ± 3 versus 22 ± 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.10 ± 0.02 versus 0.09 ± 0.02 mg/dL; n = 4). Therefore, we decided to use YB-1 ASOA for subsequent experiments to investigate in vivo efficacy and potential mechanism of action.

Figure 1.

Construction of YB-1 ASOs and Their Effects on YB-1 mRNA and Protein Expression In Vitro

(A) Schematic structures of several types of YB-1 ASOs. (B) Tm values of YB-1 ASO duplexes with DNA and RNA target strands. (C) qRT-PCR of human YBX1 mRNA in HUVECs, HPAECs, and MIA PaCa-2 cells transfected with YB-1 ASOs or control ASO (normalized to B2M). n = 3. (D) Immunoblots for YB-1 protein in HUVECs, HPAECs, and MIA PaCa-2 cells transfected with YB-1 ASOs or control ASO (5 nM). β-actin is the loading control. (E) Effects of i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA, YB-1 ASOL, or control ASO (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight) on liver function, evaluated by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and T. Bil values. *p < 0.01; n = 4 per group. Data are means ± SD.

Antitumor Efficacy of i.v. Administered YB-1 ASOA in Mice Harboring Subcutaneous Tumor Xenografts

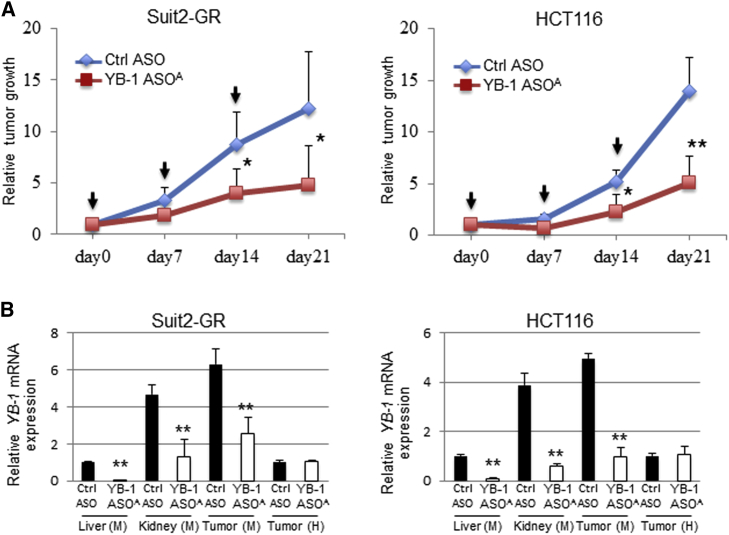

YB-1 ASOA, administered intravenously (i.v.), inhibited tumor growth by more than 50%, compared with control injected mice, on day 21 in the Suit2-GR and HCT116 xenograft models (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (Figure 2A). The xenograft tumors consisted of mouse stromal cells and implanted human cancer cells; thus, we evaluated knockdown efficiency of mouse and human YBX1 in tumor tissues using qRT-PCR with different primers to detect mouse and human YBX1. Expression of mouse YBX1 mRNA was significantly inhibited in liver, kidney, and tumor tissues in mice receiving i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA, compared with controls (**p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). In contrast, human YBX1 expression in tumor tissues was not inhibited.

Figure 2.

Antitumor Efficacy of i.v. Administered YB-1 ASOA in Mice Harboring Subcutaneous Tumor Xenografts

(A) Antitumor efficacy of i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight) in mice bearing HCT116 or Suit2-GR xenografts. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 7 per group. Black arrows represent administered time points of ASOs. (B) qRT-PCR of mouse YBX1 mRNA in liver, kidney, or tumor and human YBX1 mRNA in tumor tissues from mice harboring HCT116 and Suit2-GR xenografts and receiving YB-1 ASOA treatments (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight). **p < 0.001; n = 7 per group. Values are normalized to those for mouse or human 18S rRNAs. Data are means ± SD.

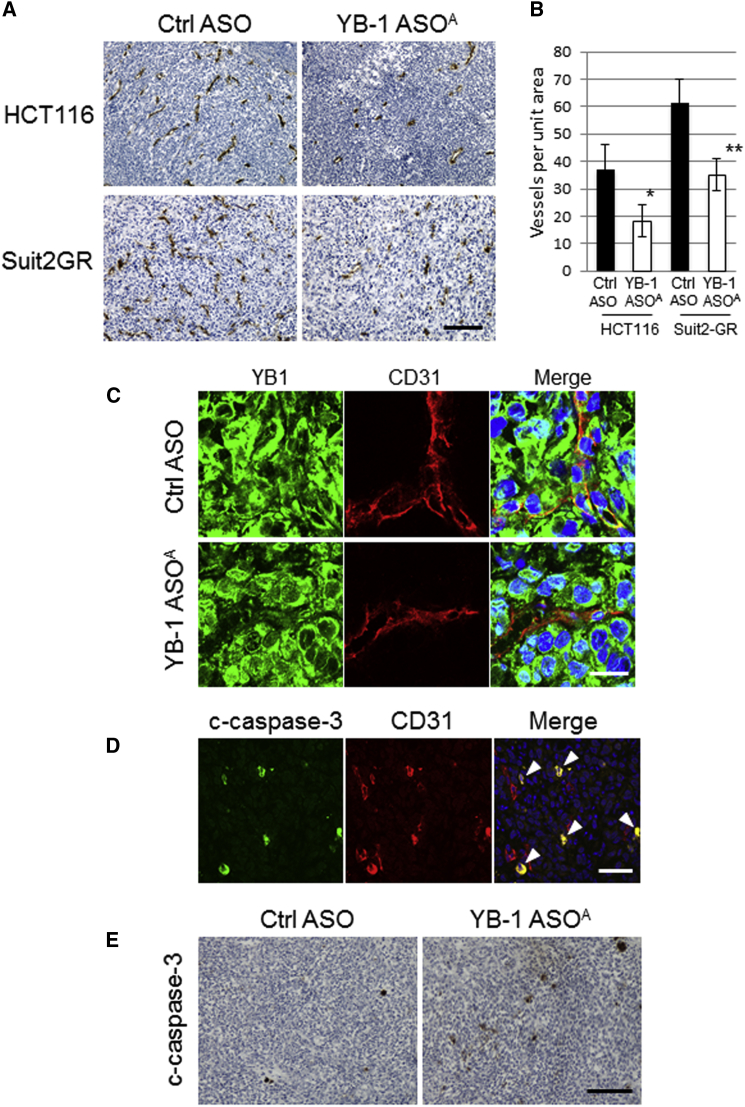

Antitumor Efficacy of i.v. Administered YB-1 ASOA Is Mediated by Antiangiogenic Effects

We hypothesized that the antitumor efficacy of YB-1 ASOA was mediated by angiogenesis inhibition rather than by a direct effect to cancer cells in the subcutaneous tumors, and we examined microvascular density in the tumor tissues by immunostaining for the mouse angiogenic marker CD31 (Figure 3A). In mice given i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA, the numbers of angiogenic vascular endothelial cells in HCT116 and Suit2-GR tumors decreased to 48% and 57%, respectively, compared with those in controls (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (Figure 3B), whereas the level of CD31 staining was not high in the liver or kidneys and was not affected by YB-1 ASOA i.v. administration (Figure S3). Next, we performed double staining for CD31 and YB-1 to analyze YB-1 expression in angiogenic endothelial cells in subcutaneous Suit2-GR tumors. YB-1 expression was greatly reduced in CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells in tumor tissues after i.v. administration of YB-1 ASOA, but not in most cancer cells (Figure 3C). This was consistent with the qRT-PCR results for mouse and human YBX1 mRNA expression (Figure 2B).

Figure 3.

i.v. Administered YB-1 ASOA Suppresses Tumor Growth In Vivo through Antiangiogenic Effects on Host Vascular Cells

(A) Representative immunostaining images showing CD31 in HCT116 and Suit2-GR tumors after YB-1 ASOA treatment (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight). Scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Quantification of microvascular density, assessed by CD31 staining per field, in HCT116 and Suit2-GR tumor tissues. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 6. Data are means ± SD. (C) Representative immunostaining images for YB-1 and CD31 in Suit2-GR tumor tissues in mice treated with YB-1 ASOA or control ASO (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight). Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Representative immunostaining images showing cleaved caspase-3 (c-caspase-3) and mouse CD31 in Suit2-GR tumor tissues from mice receiving i.v. YB-1 ASOA treatment (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight). Yellow signal (arrowhead) in merged images represents apoptosis (c-caspase-3) in CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. The fluorescent signal images (C and D) were obtained using immunofluorescence laser confocal microscopy. (E) Immunostaining of c-caspase-3 in Suit2-GR tumors from mice treated with i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight). YB-1 ASOA-treated, but not control, tumors had apoptotic cells. Scale bar, 200 μm.

To further examine the cause of decreased microvascular density in YB-1 ASOA-treated tumors, we evaluated apoptosis induction in vascular endothelial cells in HCT116 and Suit2-GR tumors treated with YB-1 ASOA. Apoptosis in angiogenic vascular cells was assessed by double staining for CD31 and cleaved caspase-3, a member of the cysteine-aspartic acid protease (caspases) family. Those cells that were intensely stained for cleaved caspase-3 were co-localized with angiogenic endothelial cells, positive for mouse CD31, in tumors treated with YB-1 ASOA (Figure 3D, arrowheads). In contrast, only a few cells positive for cleaved caspase-3 were detected in the control tumors (Figure 3E). These results suggest that i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA efficiently distributed to tumor vessels and induced apoptosis in angiogenic vascular endothelial cells, resulting in the inhibition of tumor growth.

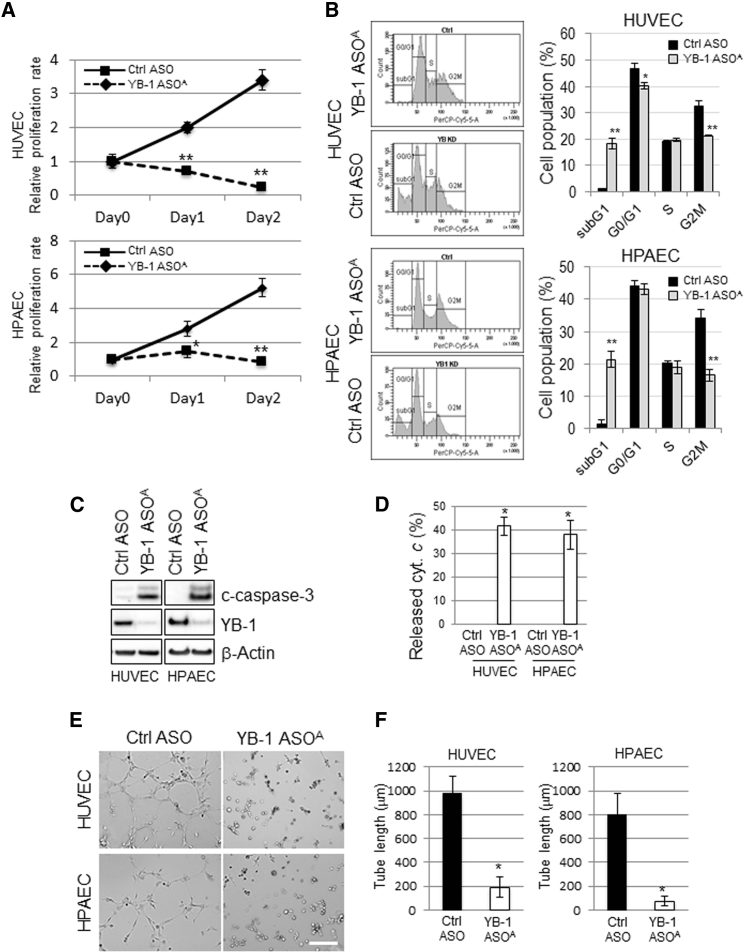

YB-1 ASOA Inhibits Proliferation and Tube Formation of Vascular Endothelial Cells

To explore the mechanism of YB-1 ASOA on inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, phenotypic changes by YB-1 knockdown were examined in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs). Transfection with YB-1 ASOA significantly inhibited proliferation of HUVECs and HPAECs (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (Figure 4A) and decreased the proportion of cells in G2/M phase to approximately 60% and 50% of the controls in YB-1 ASOA-treated HUVECs and HPAECs, respectively. Conversely, the proportion at sub-G1 phase, a fraction of apoptotic cells, was increased approximately 20-fold in HUVECs and HPAECs treated with YB-1 ASOA compared with controls (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Involvement of YB-1 in Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Tube Formation in Vascular Endothelial Cells

HUVECs and HPAECs were transfected with YB-1 ASOA or control ASOA (5 nM) and subjected to the following analyses. (A) Cell proliferation analysis with the WST-8 assay. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 3. (B) Cell-cycle distribution, analyzed in HUVEC and HPAEC by staining the DNA content with propidium iodide. The distribution was measured by flow cytometry. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 3. (C) Western blot analysis shows robustly increased c-caspase-3 (apoptosis) and decreased YB-1 levels in YB-1 ASOA-transfected cells. β-actin is the loading control. (D) Cytochrome c release from the IMS was detected in HUVECs and HPAECs transfected with YB-1 ASOA in the presence of a pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK, under immunofluorescence laser confocal microscopy. Data were obtained from 50 cells in each of three independent experiments. Quantitated levels of released cytochrome c were higher in cells with YB-1 ASOA transfection than in controls. *p < 0.001. (E) Representative images showing tube formation in HUVEC and HPAEC cultures transfected with YB-1 ASOA or control. Scale bar, 200 μm. (F) Quantitation of total tube length in 10 randomly chosen images using ImageJ software. *p < 0.001. Data are means ± SD.

Western blot analysis also showed robust cleavage of caspase-3, indicating induction of apoptosis, in cells with YB-1 knockdown, but not in controls (Figure 4C). We further evaluated apoptosis by the release of a pro-apoptotic protein, cytochrome c, from the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS), an upstream event of caspase activation.25 Cytochrome c release from mitochondrial marker protein TOMM20 (Figure S4) was observed in 41.6% of HUVECs and 38% of HPAECs with YB-1 knockdown, whereas no cytochrome c release was observed in controls (**p < 0.001) (Figure 4D).

We next examined the effects of YB-1 ASOA on angiogenesis by in vitro tube formation assay mimicking capillary-like structure formation of angiogenic endothelial cells in the critical process of angiogenesis in vivo.19 Tube formation was significantly inhibited to approximately 20% and 10% of control levels in HUVECs and HPAECs, respectively, transfected with YB-1 ASOA (*p < 0.01) (Figures 4E and 4F).

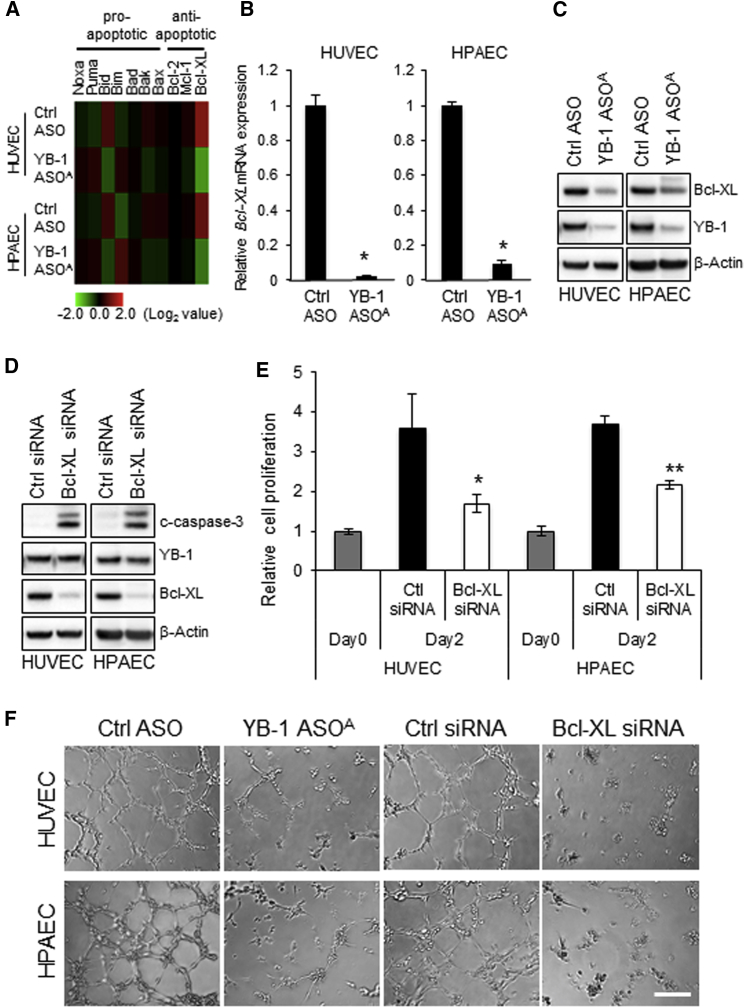

YB-1 ASOA-Mediated Bcl-xL Reduction Induces Apoptosis and Inhibition of Tube Formation in Vascular Endothelial Cells

To explore factors downstream of YB-1 signaling, we examined gene expression profiles in YB-1 ASOA-transfected HUVEC and HPAEC using cDNA microarray analysis. The microarray analysis showed that expression of Bcl-xL, a member of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family of proteins, was significantly decreased in YB-1 ASOA-transfected cells (*p < 0.001) (Figure 5A). qRT-PCR and western blot confirmed repression of Bcl-xL expression at both mRNA and protein levels in HUVECs and HPAECs with YB-1 knockdown (Figures 5B and 5C). Consistently, transfection of Bcl-xL siRNA induced apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3 [c-caspase-3]) in HUVEC and HPAEC but did not change YB-1 expression (Figure 5D). Bcl-xL knockdown inhibited cell proliferation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (Figure 5E) and tube formation (Figure 5F) in a manner similar to YB-1 ASOA transfection in HUVECs and HPAECs. That is, formation of capillary-like structures was impaired similarly with both YB-1 and Bcl-xL knockdown, indicating that Bcl-xL acted downstream of the YB-1 signal. We assessed whether Bcl-xL overexpression reverses inhibition of vascular endothelial cell tube formation by YB-1 ASOA. Transduction of Bcl-xL by adeno-associated virus 2 particles partially rescued the YB-1 knockdown-mediated impairment of tube formation in HUVECs and HPAECs treated with YB-1 ASOA, suggesting that other factors downstream of YB-1, in addition to Bcl-xL, may be involved in tube formation in vascular endothelial cells (Figure S5; Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Figure 5.

YB-1 ASOA-Induced Apoptosis and Inhibition of Tube Formation Are Mediated by Bcl-xL Reduction in Vascular Endothelial Cells

(A) Heatmap analysis of cDNA microarray data showing highly downregulated Bcl-xL expression, among Bcl-2 family genes, in HUVECs and HPAECs transfected with YB-1 ASOA (5 nM). (B) Downregulation of Bcl-xL expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (normalized to values for 18S). *p < 0.01; n = 3. Data are means ± SD. (C) Immunoblots for Bcl-xL and YB-1 in HUVECs and HPAECs transfected with YB-1 ASOA or control ASO (5 nM). β-actin is the loading control. (D) Western blot analysis shows an increase in c-caspase-3 but no change in YB-1 protein levels in HUVECs and HPAECs transfected with Bcl-xL siRNA (5 nM). (E) Cell proliferation, assessed by WST-8 assay, was decreased in HUVECs and HPAECs by transfection with Bcl-xL siRNA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (F) Capillary-like tube formation was inhibited by transfection with Bcl-xL siRNA or YB-1 ASOA in HUVECs and HPAECs. Scale bar, 200 μm.

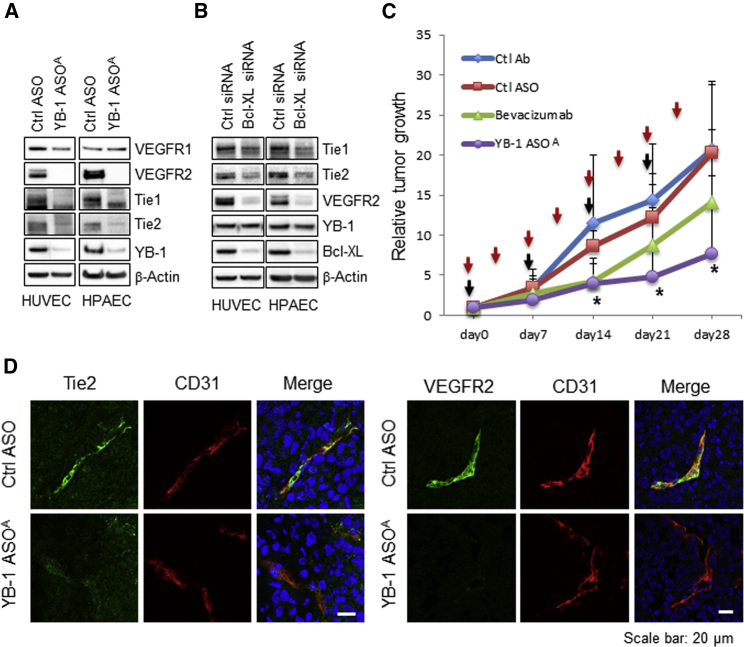

VEGFR2 and Tie Receptor Expression Is Inhibited by YB-1/Bcl-xL Knockdown in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells

We hypothesized that YB-1/Bcl-xL knockdown-mediated apoptosis may be related to the VEGF and VEGFR or angiopoietin/Tie pathway, because VEGF-VEGFR and angiopoietin-Tie receptor systems are the two major signaling pathways critical for a variety of vascular endothelial cell functions.26, 27, 28 Proliferation of HUVECs and HPAECs was moderately enhanced under the presence of a high concentration of VEGF (5 times higher than the manufacturer’s endothelial medium) or angiopoietin-1 (400 ng/mL) in a culture medium, but YB-1 ASOA-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation was not affected under the same culture conditions (Figure 6A). YB-1 protein expression or YB-1 knockdown efficiency was not changed by addition of VEGF or angiopoietin-1 (Figures S6A and S6B) or withdrawal of VEGF (Figures S6C and S6D) in the culture media in HUVECs and HPAECs. Expression of VEGFR2, Tie1, and Tie2, but not VEGFR1, was significantly reduced in YB-1 ASOA-transfected HUVECs and HPAECs (Figure 6A). Bcl-xL knockdown also decreased levels of these receptors, although it did not change YB-1 expression (Figure 6B). The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk did not affect the decreased VEGFR2 expression caused by YB-1 knockdown, whereas it inhibited cleavage of its target caspase-3 (Figure S7). These results suggest that YB-1 regulates expression of VEGFR2 and Tie receptors via an upstream Bcl-xL-mediated pathway, irrespective of caspase activation.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of YB-1/Bcl-xL Downregulates VEGFR2 and Tie-1/-2 Expression in Angiogenic Endothelial Cells in Tumor Microenvironments

(A and B) Western blot analysis showing inhibition of VEGFR2 and Tie-1/-2 expression in HUVECs or HPAECs transfected with YB-1 ASOA (5 nM) (A) or Bcl-xL siRNA (20 nM) (B). β-actin is the loading control. (C) Antitumor efficacy of YB-1 ASOA treatment (once per week for 4 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight) was superior to that of bevacizumab (twice per week for 4 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight) in mice bearing Suit2-GR xenografts. *p < 0.05; n = 9. Data are means ± SD. Red and black arrows represent administered time points of bevacizumab and ASOs, respectively. (D) Immunohistochemistry for VEGFR2, Tie2, and CD31 in the Suit2-GR tumors using laser confocal microscopy. The images show inhibition of Tie2 signals in CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells in tumor tissues treated with i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA (once per week for 4 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight), but not in the controls. Scale bar, 20 μm.

VEGFR2 and Tie2 Expression Is Inhibited in Suit2-GR Subcutaneous Tumors Treated with i.v. Administered YB-1 ASOA

We then compared YB-1 ASOA and an anti-VEGF antibody (bevacizumab) for antitumor efficacy in vivo. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited by YB-1 ASOA treatment (*p < 0.05 on days 14–28 versus the control ASO group). In contrast, the antitumor efficacy of bevacizumab was inefficient, with no significant reduction in tumor volumes compared with a control antibody-treated group (Figure 6C).To examined why bevacizumab-insensitive Suit2-GR tumors were susceptible to YB-1 ASOA treatment, we carried out the immunohistochemistry of VEGFR2 and Tie2 receptors in Suit2-GR subcutaneous tumor tissues in mice receiving i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA, because YB-1 knockdown inhibited the expression of Tie2 receptor, another major mediator of angiogenesis besides VEGF/VEGFR2, in HUVECs and HPAECs. Tie2 expression was greatly decreased in subcutaneous Suit2-GR tumor tissues treated with YB-1 ASOA compared with those in controls (Figure 6D).

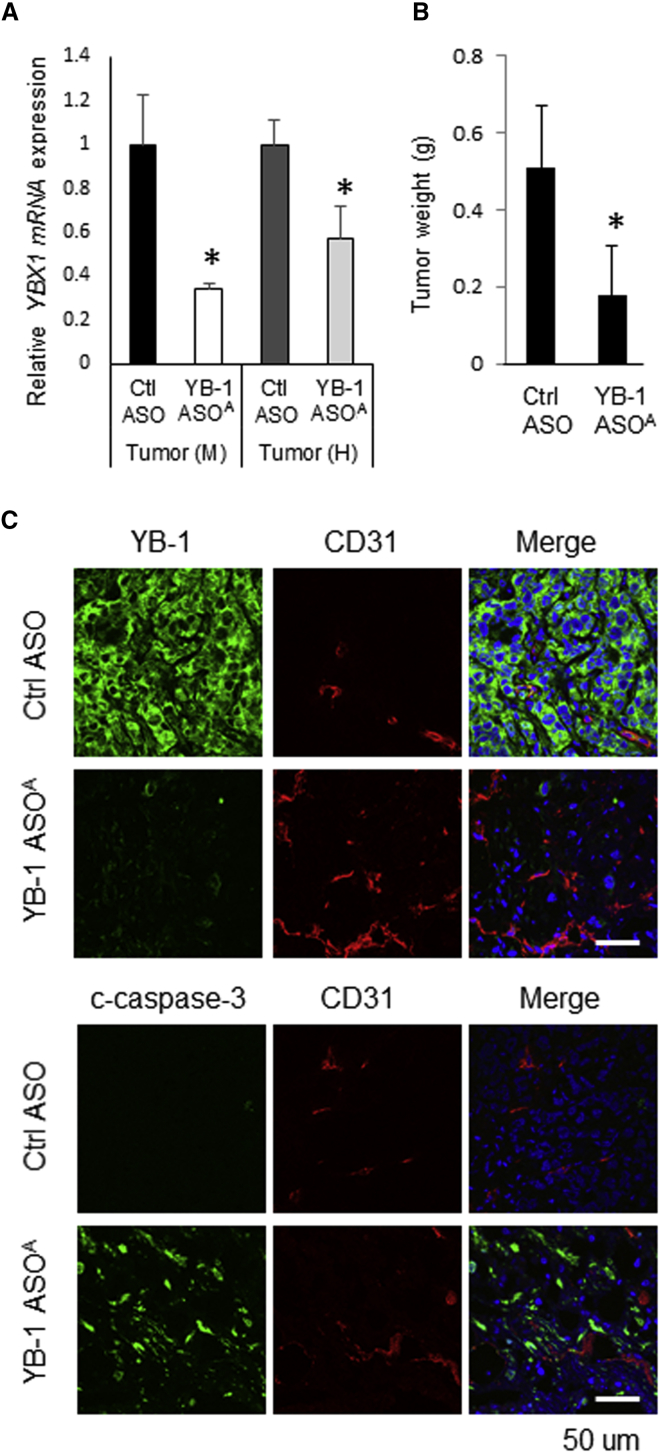

Antitumor Efficacy of i.p. Administered YB-1 ASOA in Mice Harboring Peritoneally Disseminated Tumors

YB-1 ASOA, when administered intraperitoneally (i.p.), significantly inhibited not only mouse but also human YBX1 mRNA expression in peritoneally disseminated RMG-1 tumors (p < 0.05; n = 5) (Figure 7A). Accordingly, i.p. administered YB-1 ASOA significantly suppressed the growth of disseminated RMG-1 tumors compared with the controls (p < 0.05 on days 21) (Figure 7B). Correspondingly, immunohistochemical analysis showed decreased YB-1 and increased cleaved caspase-3 expression not only in mouse CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells but also in most human ovarian cancer cells, in disseminated tumors treated with i.p. administered YB-1 ASOA (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Antitumor Efficacy of i.p. Administered YB-1 ASOA in Mice Harboring Peritoneal Dissemination

(A) qRT-PCR analysis shows an inhibition of mouse and human YBX1 expression in peritoneally disseminated RMG-1 tumors treated with i.p. administered YB-1 ASOA. *p < 0.05; n = 3. Values are normalized to those for mouse and human 18S rRNAs. (B) Disseminated RMG-1 tumor growth was inhibited on day 21 in mice treated with YB-1 ASOA (once per week for 3 weeks at 10 mg/kg body weight) compared with control ASOs. *p < 0.05; n = 5. Data are means ± SD. (C) Immunohistochemistry for CD31 and YB-1 or c-caspase-3 using laser confocal microscopy. The images show decreased YB-1 and increased c-caspase-3 levels in not only CD31-positive angiogenic endothelial cells but also most disseminated RMG-1 cancer cells after i.p. administration of YB-1 ASOA. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we have established a platform of AmNA-modified YB-1 targeted ASOs that inhibit multiple angiogenic signals (YB-1/Bcl-xL/VEGFR2 and YB-1/Bcl-xL/Tie signaling axes) and elicit apoptosis of tumor vessels in several xenograft models, suggesting a potential of YB-1 ASOA as a novel tumor dormancy therapy.

To elucidate the role of YB-1 in angiogenesis in a tumor microenvironment, we screened the ASO sequences to inhibit YB-1 expression and then generated chemically modified YB-1 ASOA and YB-1 ASOL for in vivo use, which were confirmed for higher thermal stability (Figure 1B) and more efficient knockdown of YB-1 (Figure 1C) in cancer and vascular endothelial cells compared with YB-1 ASONA. We next compared two modified YB-1 ASOs and found that YB-1 ASOA had no toxicity, unlike YB-1 ASOL, which showed hepatotoxicity with elevated ALT and T. Bil in blood chemistry tests (Figure 1E). A study has shown RNase H1-dependent hepatotoxicity caused by gapmer-structured ASOs, such as LNA-modified ASOs.29 The toxicity of AmNA-ASOs has been little studied. Because the structural design of YB-1 ASOA was identical to that of YB-1 ASOL as a gapmer-type modification, the difference in hepatotoxicity might be explained by a higher RNase H1-independent toxicity of LNA-ASOs compared with AmNA-ASOs, whereas α-L-LNA-modified ASOs have been developed to reduce hepatotoxicity but represent a higher propensity for immune stimulation.30 Therefore, we employed YB-1 ASOA to examine the role of YB-1 in tumor growth and angiogenesis in xenograft tumor mice models.

Because YB-1 is a negative regulator for apoptosis in cancer cells,22, 31 we first hypothesized that YB-1 ASOA acted directly on cancer cells, suppressed their YB-1 expression and induced apoptosis. However, when YB-1 ASOA was administered i.v. to subcutaneous xenografts, the outcome was different from our hypothesis, with YB-1 suppression not in the human cancer cells but solely in the mouse cells (Figure 2D). This indicates that the antitumor efficacy observed in i.v. treated xenografts was probably not caused by direct effects on the cancer cells, even though YB-1 ASOA was distributed to tumor tissues, as well as kidneys (Figures 2A and 2B). Our second hypothesis was that YB-1 ASOA affected tumor growth by downregulating vascularization in the tumor tissues,32 because YB-1 is overexpressed in tumor vessels in a variety of solid tumors13 and the activity of phosphorothioate ASOs has been shown in the tumor microenvironment.33, 34, 35 The immunohistochemical analysis by double staining of CD31 and YB-1 in subcutaneous tumor tissues showed that i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA suppressed YB-1 expression primarily in mouse vascular endothelial cells and induced their apoptosis, leading to angiogenesis inhibition. This may be caused by YB-1 ASOA reagents being delivered to the tumor vessels efficiently rather than inside the tumor nests. Moreover, gene mutations rarely occur in the tumor vessels, indicating that YB-1 ASOA resistance may not be frequently induced by YB-1 ASOA treatment.

A novel pathway for YB-1 ASOA-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis may be through suppressing Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL, major antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 protein family, because Bcl-2 promotes angiogenesis in tumor microenvironments by enhancing VEGF expression and HIF-1 transcriptional activity25, 36, 37, 38 and Bcl-xL upregulates angiogenesis through secretion of interleukin-8, an angiogenic factor, from cancer cells.39, 40, 41 Our microarray analysis showed the interaction of YB-1 with the Bcl-xL signal in vascular endothelial cells. It has been reported that osteopontin-induced angiogenesis is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, an inducer of YB-1 activation,42 and by ERK signals, concomitant with upregulation of Bcl-xL and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB),43 and that co-stimulation of VEGF and angiopoietin-1 promotes angiogenesis with upregulated Bcl-xL and downregulated caspase-3 in myocardial infarction heart.44 Thus, we examined the involvement of Bcl-xL in VEGF/VEGFR and angiopoietin/Tie signals in vascular endothelial cells. In HUVECs and HPAECs treated with YB-1 ASOA and Bcl-xL siRNA, YB-1 knockdown-mediated Bcl-xL reduction inhibited the expression of VEGFR2 and Tie-1/-2 receptors, irrespective of caspase activation. These results indicate that the mechanism of antiangiogenic function of YB-1 ASOA may be mediated by the blockade of VEGF/VEGFR2 and angiopoietin/Tie signaling pathways. The mechanism was examined in human vascular endothelial cell lines, because mouse cell lines of vascular endothelia are not established and our final goal is a clinical application. It was confirmed that YB-1 ASOA incubation without transfection reagents inhibited YB-1 expression in mouse tumor cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S8), although the YB-1 ASOA activity plateaued around 500–750 nM. Inhibited VEGFR2/Tie signals and induction of apoptosis in mouse tumor vessels was likely induced by the YB-1 knockdown effect, because the sensitivity to YB-1 ASOA was higher in vascular endothelial cells compared with tumor cells.

The two signal pathways of VEGF/VEGFR and angiopoietin/Tie independently regulate tumor angiogenesis,45, 46 indicating that angiogenic inhibitors affecting both pathways would be highly effective compared with single-target reagents. Because VEGFR2 and Tie2 expression was inhibited by i.v. administered YB-1 ASOA in angiogenic endothelial cells in a tumor microenvironment, it is not surprising that YB-1 ASOA, when given i.v., induced apoptosis to tumor vessels in a bevacizumab-resistant xenograft tumor model. The safety potential of YB-1 ASOA was confirmed by body weight (Figure S9) and blood examinations (Table 1). In addition, YB-1 ASOA, when given i.p, distributed to peritoneally disseminated tumors more efficiently compared with i.v. administration to subcutaneous tumors (Figure S10), inhibited both mouse and human YB-1 expression, and exhibited higher antitumor efficacy against peritoneal dissemination via the mechanism of direct apoptosis to cancer cells (Figure 7). Therefore, YB-1 ASOA, unlike anti-VEGF antibodies or tyrosine kinase inhibitors of VEGFR,47 could act not only on tumor vessels but also on cancer cells, which may depend on the distribution routes and infiltration efficiency of ASO reagents into tumor nests. For future clinical applications, we are evaluating the maximum tolerated dose and therapeutic windows using three animal species (mouse, rat, and cynomolgus monkey).

Table 1.

Blood Tests in Mice after i.v. Administration of YB-1 ASOA

| Suit2-GR Subcutaneous Tumor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (102/μL) | RBC (104/μL) | HGB (g/dL) | HCT (%) | PLT (104/μL) | |

| Saline | 43 ± 5 | 752 ± 22 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 37.3 ± 1.4 | 94.2 ± 27.0 |

| Ctrl ASO | 29 ± 12 | 779 ± 39 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 38.5 ± 2.1 | 100.5 ± 33.3 |

| YB-1 ASOA | 54 ± 14 | 741 ± 48 | 11.8 ± 0.9 | 37.4 ± 2.4 | 90.4 ± 26.9 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | Cre (mg/dL) | AST (IU/L) | ALT (IU/L) | T. Bil (mg/dL) | |

| Saline | 32.4 ± 3.7 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 147 ± 103 | 37 ± 15 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Ctrl ASO | 27.9 ± 5.4 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 170 ± 183 | 45 ± 19 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| YB-1 ASOA | 24.6 ± 3.5 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 158 ± 71 | 58 ± 29 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| HCT116 Subcutaneous Tumor | |||||

| WBC (102/μL) | RBC (104/μL) | HGB (g/dL) | HCT (%) | PLT (104/μL) | |

| Ctrl ASO | 48 ± 8 | 715 ± 55 | 13.1 ± 0.3 | 35.7 ± 2.7 | 136.2 ± 10.8 |

| YB-1 ASOA | 39 ± 9 | 696 ± 43 | 13.0 ± 0.6 | 35.5 ± 2.3 | 123.7 ± 40.5 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | Cre (mg/dL) | AST (IU/L) | ALT (IU/L) | T. Bil (mg/dL) | |

| Ctrl ASO | 21.2 ± 2.0 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 80 ± 10 | 26 ± 3 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| YB-1 ASOA | 17.4 ± 2.6 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 148 ± 39 | 77 ± 19 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

YB-1 ASOA or control (Ctrl) ASOs (10 mg/kg body weight [BW]) were i.v. administered to nude mice harboring Suit2-GR or HCT116 subcutaneous tumors once per week for 3 weeks. Blood samples were collected 1 week after the final administration of ASOs and subjected to the blood examinations. WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; HGB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet.

In conclusion, YB-1/Bcl-xL/VEGFR2 and YB-1/Bcl-xL/Tie signaling axes play important roles in angiogenesis and YB-1 ASOA could exert antitumor efficacy against a variety of cancers by inducing apoptotic changes in new blood vessels. YB-1 ASOA may, therefore, exemplify a novel strategy of tumor dormancy therapy.

Materials and Methods

ASOs

Phosphorothioate ASOs containing DNA, LNA, or AmNA monomers (Figure 1A; Figure S1) were synthesized using an automated DNA synthesizer by GeneDesign (Ibaraki, Japan), based on methods described by Nishina et al.48 The 3′ end of LNA-ASOs or AmNA-ASOs was not chemically modified because of very low efficiency of AmNA-ASO synthesis. To select YB-1 ASOs with high knockdown efficiency, we performed screening experiments using real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) in several cancer cell lines transfected with LNA-type ASOs targeting 64 sites on the YB-1 mRNA. In the selected LNA-ASOs, we replaced LNA monomers at the flanked regions of the ASOs with AmNA monomers (Figure 1A) to compare in vitro knockdown efficiency and in vivo safety potentials between LNA-ASOs and AmNA-ASOs. Finally, we changed the length of ASOs from 13 to 18 nucleotides to optimize the length of YB-1 ASOs with the highest knockdown efficiency. Evaluation of ASO properties was described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture

The primary human endothelial cells, HUVECs (C2519A) and HPAECs (CC-2530), were from Lonza (Tokyo, Japan). Human pancreatic MIA PaCa-2 and colorectal HCT116 carcinoma cell lines were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and the ovarian cancer RMG-1 cell line was from Japanese Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). The gemcitabine-resistant human pancreatic Suit2-GR cancer cell line was a gift from Dr. Masao Tanaka (Kyushu University).49 Suit2-GR and HCT116 cell lines stably expressing luciferase were established as previously reported.50 HUVECs and HPAECs were cultured in EGM-2 basal media (Lonza) supplemented with the SingleQuots Kit (Lonza). HCT116 and RMG-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Nacalai Tesque, Tokyo, Japan), and MIA PaCa-2 and Suit2-GR cells were cultured in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque), all supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Tokyo, Japan), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere equilibrated with 95% air and 5% CO2.

Antibodies and Reagents

We obtained antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signal, Tokyo, Japan), CD31 (BD Pharmingen, Tokyo, Japan), cytochrome c (BD Pharmingen), Tom20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), VEGFR1 (Abcam, Tokyo, Japan), VEGFR2 (Cell Signal), Bcl-xL (Cell Signal), Tie1 (Santa Cruz), Tie2 (Santa Cruz), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A polyclonal antibody against recombinant YB-1 was provided by Dr. Michihiko Kuwano (Kyushu University). The VECTASTAIN Elite HRP ABC Kit (rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG] and rat IgG) and Peroxidase Substrate Kit were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA).

In Vitro Transfection of ASOs and siRNAs

Cells were plated at 3 × 103–1 × 104 cells/cm2 24 hr before transfection. Cells were transfected with siRNA duplexes or ASOs at the indicated concentration using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using a High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche, Tokyo, Japan). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with a QuantiTect SYBR Green Reverse Transcription-PCR Kit (Roche) on a Light Cycler 480 II instrument (Roche). The data from qRT-PCR were normalized to the data for a housekeeping gene, either 18S rRNA or human B2M. PCR amplification was performed in three independent experiments. The probe to detect YB-1 was Universal ProbeLibrary Probe #16 (Roche). Sets of primers were 5′-cgc agt gta gga gat gga gag-3′ and 5′-gaa cac cac cag gac ctg taa-3′ for YB-1; 5′-gta acc ccg ttg aac ccc att-3′ and 5′-cca tcc aat cgg tag tag cg-3′ for 18S; and ProbeLibrary sets for human B2M gene (Roche).

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from control or YB-1 ASOA-transfected HUVECs and HPAECs. The quality of RNA in each sample was evaluated using Expression RNA Analysis kits and an automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Biotinylated cDNA was prepared from 0.5 μg total RNA using an Ambion WT Expression Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan) and hybridized with Human Gene 2.1 ST Array strips at 45°C for 16 hr. Array slides were washed, stained, and scanned in the GeneAtlas System (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Microarray data analysis was performed using GeneSpring GX 13.1 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Western Blot Analysis

Cultured cells were harvested into SDS buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 0.5% glycerol, 2% SDS). Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Extract samples (15 μg protein) were electrophoresed on precast acrylamide gels (Invitrogen). The protein bands were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (New England Biolabs, Tokyo, Japan). The membranes were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hr. Chemiluminescent detection was performed with the ECL Prime reagent (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Fresh tissues were embedded in OCT freezing medium and frozen using Histo-Tek PINO (AS ONE, Osaka, Japan). Tissues were sectioned at an 8 μm thickness, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Wako, Osaka, Japan) for 15 min at room temperature, and pretreated with methanol containing 1% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase. The sections were incubated with a primary antibody at 4°C overnight and the secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature, followed by histochemical detection using the ABC system (Vector Laboratories) with hematoxylin counterstaining. Images were acquired with an Eclipse 55i upright microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Immunofluorescence images were acquired with a C2 confocal microscope (Nikon) after incubation with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). For analysis of cytochrome c release, HUVECs and HPAECs were grown on coverslips (Matsunami, Osaka, Japan). Cells were transfected with YB-1 ASOA in the presence of 100 μM z-VAD-FMK, a broad caspase inhibitor. Cells were fixed and immunostained for cytochrome c as described earlier.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was quantified with Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, on days 0, 1, and 2 after transfection. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a GloMax-Multi+ Microplate Multimode Reader (Promega, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell-Cycle Analysis

Cells were harvested with trypsin, washed with PBS, and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 1 hr. After resuspension in PBS containing 0.1% BSA, cells were treated with RNase (50 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 min, stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/mL; Nacalai Tesque) for 15 min, and subjected to cell-cycle analysis using a flow cytometer (FACS Canto II; BD Biosciences).

Tube Formation Assay with Human Microvascular Endothelial Cells

Growth factor-depleted Matrigel (Corning, Tokyo, Japan) was added to plates at 150 μL/cm2 and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow the gel to solidify. Human microvascular endothelial cells (HUVECs or HPAECs, 3.5 × 104 cells/cm2) were then plated onto the Matrigel. After 5.5 hr incubation at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2, bright-field images were acquired with Digital Sight DS-Qi1Mc (Nikon). Ten images per sample were obtained, and the total length of tube-like structures in each field was measured using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Animals and Study Approval

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Kyushu University. Female 6-week-old athymic nude mice (BALB/cAnNCrj-nu) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan (Yokohama, Japan) and allowed to acclimatize for 1 week before the start of experiments.

In Vivo Treatments

Subcutaneous tumor models were prepared by injecting nude mice with pancreatic Suit2-GR or colorectal HCT116 cancer cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) in the flanks. After 1 week, YB-1 ASOA solutions were administered via tail vein once per week for 3 weeks at a dose of 10 mg/kg (days 0, 7, and 14). Tumor size was calculated using the formula a × 1/2 × b2 (a, long; b, short tumor distance) each week. On day 21, tumor, liver, and kidney tissues were obtained to determine knockdown efficiency and antiangiogenic effects of the treatments by immunohistochemistry for CD31 and cleaved caspase-3. Blood samples were collected and subjected to hematology and blood chemistry tests to assess the safety of i.v. administered YB-1 ASO. In a separate experiment, YB-1 ASOA (10 mg/kg) was administered i.v. once per week for 4 weeks in mice with subcutaneous Suit2-GR tumors, and this treatment was compared with bevacizumab antibody (10 mg/kg), given twice per week for the same period. Efficacy was determined by assessing tumor growth and microvascular density in tumor tissues on day 28.

Peritoneal dissemination was generated by i.p. implantation of RMG-1 ovarian cancer cells in nude mice (5 × 105 cells/mouse). After 1 week, YB-1 ASOA (10 mg/kg) was administered i.p. once per week for 3 weeks (days 0, 7, and 14). Antitumor efficacy was evaluated by tumor weight on day 21.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 12 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All data are represented as means ± SD. Student’s t test was used to compare mean values between two groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

K.N. invented the study design. K. Setoguchi, L.C., S. Obchoei, N.H., F.H., K.K., and K. Shinkai performed in vitro and in vivo experiments and data analyses. S. Obika and T.Y. contributed to the design of ASO structures and sequences. F.W. and M.H.-S. analyzed the properties of ASOs. K. Setoguchi and K.N. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hirokazu Nankai (GeneDesign, Inc.) and Izumi Nakamura and Masako Naito (Kyushu University) for technical assistance. We thank Drs. Masao Tanaka and Michihiko Kuwano (Kyushu University) for providing the pancreatic cancer Suit2-GR cell line and YB-1 antibody, respectively. This study was supported by a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (14524896 to K.N.) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (16ck0106082h0003 to K.N.) and KAKENHI (Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (16H05402 to K.N.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). K. Setoguchi was supported by a grant from the Research Resident Development Program of the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, Japan.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Materials and Methods and ten figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2017.09.004.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Crooke S.T. Antisense strategies. Curr. Mol. Med. 2004;4:465–487. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu H., Lima W.F., Zhang H., Fan A., Sun H., Crooke S.T. Determination of the role of the human RNase H1 in the pharmacology of DNA-like antisense drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17181–17189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galarneau A., Min K.L., Mangos M.M., Damha M.J. Assay for evaluating ribonuclease H-mediated degradation of RNA-antisense oligonucleotide duplexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005;288:65–80. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-823-4:065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vester B., Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acid): high-affinity targeting of complementary RNA and DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13233–13241. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahlestedt C., Salmi P., Good L., Kela J., Johnsson T., Hökfelt T., Broberger C., Porreca F., Lai J., Ren K. Potent and nontoxic antisense oligonucleotides containing locked nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5633–5638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yahara A., Shrestha A.R., Yamamoto T., Hari Y., Osawa T., Yamaguchi M., Nishida M., Kodama T., Obika S. Amido-bridged nucleic acids (AmNAs): synthesis, duplex stability, nuclease resistance, and in vitro antisense potency. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:2513–2516. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohno K., Izumi H., Uchiumi T., Ashizuka M., Kuwano M. The pleiotropic functions of the Y-box-binding protein, YB-1. BioEssays. 2003;25:691–698. doi: 10.1002/bies.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyabin D.N., Eliseeva I.A., Ovchinnikov L.P. YB-1 protein: functions and regulation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2014;5:95–110. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee M., Rancso C., Stühmer T., Eckstein N., Andrulis M., Gerecke C., Lorentz H., Royer H.D., Bargou R.C. The Y-box binding protein YB-1 is associated with progressive disease and mediates survival and drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:3714–3722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinkai K., Nakano K., Cui L., Mizuuchi Y., Onishi H., Oda Y., Obika S., Tanaka M., Katano M. Nuclear expression of Y-box binding protein-1 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer and its knockdown inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in mice tumor models. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;139:433–445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J., Lee C., Yokom D., Jiang H., Cheang M.C., Yorida E., Turbin D., Berquin I.M., Mertens P.R., Iftner T. Disruption of the Y-box binding protein-1 results in suppression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and HER-2. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4872–4879. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashihara M., Azuma K., Kawahara A., Basaki Y., Hattori S., Yanagawa T., Terazaki Y., Takamori S., Shirouzu K., Aizawa H. Nuclear Y-box binding protein-1, a predictive marker of prognosis, is correlated with expression of HER2/ErbB2 and HER3/ErbB3 in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009;4:1066–1074. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi M., Shimajiri S., Izumi H., Hirano G., Kashiwagi E., Yasuniwa Y., Wu Y., Han B., Akiyama M., Nishizawa S. Y-box binding protein-1 is a novel molecular target for tumor vessels. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1367–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evdokimova V., Tognon C., Ng T., Ruzanov P., Melnyk N., Fink D., Sorokin A., Ovchinnikov L.P., Davicioni E., Triche T.J., Sorensen P.H. Translational activation of snail1 and other developmentally regulated transcription factors by YB-1 promotes an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:402–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giménez-Bonafé P., Fedoruk M.N., Whitmore T.G., Akbari M., Ralph J.L., Ettinger S., Gleave M.E., Nelson C.C. YB-1 is upregulated during prostate cancer tumor progression and increases P-glycoprotein activity. Prostate. 2004;59:337–349. doi: 10.1002/pros.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasham A., Print C.G., Woolley A.G., Dunn S.E., Braithwaite A.W. YB-1: oncoprotein, prognostic marker and therapeutic target? Biochem. J. 2013;449:11–23. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiello L.P., Pierce E.A., Foley E.D., Takagi H., Chen H., Riddle L., Ferrara N., King G.L., Smith L.E. Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10457–10461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K.J., Li B., Winer J., Armanini M., Gillett N., Phillips H.S., Ferrara N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature. 1993;362:841–844. doi: 10.1038/362841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnaoutova I., Kleinman H.K. In vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:628–635. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akiyama K., Ohga N., Hida Y., Kawamoto T., Sadamoto Y., Ishikawa S., Maishi N., Akino T., Kondoh M., Matsuda A. Tumor endothelial cells acquire drug resistance by MDR1 up-regulation via VEGF signaling in tumor microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coles L.S., Lambrusco L., Burrows J., Hunter J., Diamond P., Bert A.G., Vadas M.A., Goodall G.J. Phosphorylation of cold shock domain/Y-box proteins by ERK2 and GSK3beta and repression of the human VEGF promoter. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5372–5378. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H., Sun R., Gu M., Li S., Zhang B., Chi Z., Hao L. shRNA-mediated silencing of Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1) suppresses growth of neuroblastoma cell SH-SY5Y in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J.H., Cui N.P., Wang S., Zhao M.Z., Wang B., Wang Y.N., Chen B.P. Overexpression of YB1 C-terminal domain inhibits proliferation, angiogenesis and tumorigenicity in a SK-BR-3 breast cancer xenograft mouse model. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6:33–42. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W., Wang H.J., Wang B., Li Y., Qin Y., Zheng L.S., Zhou J.S., Qu P.H., Shi J.H., Zhang H.S. The role of the Y box binding protein 1 C-terminal domain in vascular endothelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35:24–32. doi: 10.1089/dna.2015.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Bufalo D., Biroccio A., Leonetti C., Zupi G. Bcl-2 overexpression enhances the metastatic potential of a human breast cancer line. FASEB J. 1997;11:947–953. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.12.9337147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung D.W., Cachianes G., Kuang W.J., Goeddel D.V., Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science. 1989;246:1306–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson A.K., Dimberg A., Kreuger J., Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling—in control of vascular function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augustin H.G., Koh G.Y., Thurston G., Alitalo K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:165–177. doi: 10.1038/nrm2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasuya T., Hori S., Watanabe A., Nakajima M., Gahara Y., Rokushima M., Yanagimoto T., Kugimiya A. Ribonuclease H1-dependent hepatotoxicity caused by locked nucleic acid-modified gapmer antisense oligonucleotides. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30377. doi: 10.1038/srep30377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seth P.P., Jazayeri A., Yu J., Allerson C.R., Bhat B., Swayze E.E. Structure activity relationships of α-L-LNA modified phosphorothioate gapmer antisense oligonucleotides in animals. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2012;1:e47. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasham A., Moloney S., Hale T., Homer C., Zhang Y.F., Murison J.G., Braithwaite A.W., Watson J. The Y-box-binding protein, YB1, is a potential negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35516–35523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watnick R.S. The role of the tumor microenvironment in regulating angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006676. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong D., Kurzrock R., Kim Y., Woessner R., Younes A., Nemunaitis J., Fowler N., Zhou T., Schmidt J., Jo M. AZD9150, a next-generation antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of STAT3 with early evidence of clinical activity in lymphoma and lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:314ra185. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto Y., Loriot Y., Beraldi E., Zhang F., Wyatt A.W., Al Nakouzi N., Mo F., Zhou T., Kim Y., Monia B.P. Generation 2.5 antisense oligonucleotides targeting the androgen receptor and its splice variants suppress enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer cell growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:1675–1687. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diermeier S.D., Chang K.C., Freier S.M., Song J., El Demerdash O., Krasnitz A., Rigo F., Bennett C.F., Spector D.L. Mammary tumor-associated RNAs impact tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Cell Rep. 2016;17:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biroccio A., Candiloro A., Mottolese M., Sapora O., Albini A., Zupi G., Del Bufalo D. Bcl-2 overexpression and hypoxia synergistically act to modulate vascular endothelial growth factor expression and in vivo angiogenesis in a breast carcinoma line. FASEB J. 2000;14:652–660. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iervolino A., Trisciuoglio D., Ribatti D., Candiloro A., Biroccio A., Zupi G., Del Bufalo D. Bcl-2 overexpression in human melanoma cells increases angiogenesis through VEGF mRNA stabilization and HIF-1-mediated transcriptional activity. FASEB J. 2002;16:1453–1455. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0122fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trisciuoglio D., Desideri M., Ciuffreda L., Mottolese M., Ribatti D., Vacca A., Del Rosso M., Marcocci L., Zupi G., Del Bufalo D. Bcl-2 overexpression in melanoma cells increases tumor progression-associated properties and in vivo tumor growth. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005;205:414–421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giorgini S., Trisciuoglio D., Gabellini C., Desideri M., Castellini L., Colarossi C., Zangemeister-Wittke U., Zupi G., Del Bufalo D. Modulation of bcl-xL in tumor cells regulates angiogenesis through CXCL8 expression. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:761–771. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch A.E., Polverini P.J., Kunkel S.L., Harlow L.A., DiPietro L.A., Elner V.M., Elner S.G., Strieter R.M. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science. 1992;258:1798–1801. doi: 10.1126/science.1281554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dean N.M., Bennett C.F. Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapeutics for cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:9087–9096. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bader A.G., Vogt P.K. Phosphorylation by Akt disables the anti-oncogenic activity of YB-1. Oncogene. 2008;27:1179–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai J., Peng L., Fan K., Wang H., Wei R., Ji G., Cai J., Lu B., Li B., Zhang D. Osteopontin induces angiogenesis through activation of PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 in endothelial cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:3412–3422. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tao Z., Chen B., Tan X., Zhao Y., Wang L., Zhu T., Cao K., Yang Z., Kan Y.W., Su H. Coexpression of VEGF and angiopoietin-1 promotes angiogenesis and cardiomyocyte proliferation reduces apoptosis in porcine myocardial infarction (MI) heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2064–2069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018925108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jendreyko N., Popkov M., Rader C., Barbas C.F., 3rd Phenotypic knockout of VEGF-R2 and Tie-2 with an intradiabody reduces tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8293–8298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503168102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siemeister G., Schirner M., Weindel K., Reusch P., Menrad A., Marmé D., Martiny-Baron G. Two independent mechanisms essential for tumor angiogenesis: inhibition of human melanoma xenograft growth by interfering with either the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor pathway or the Tie-2 pathway. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3185–3191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhargava P., Robinson M.O. Development of second-generation VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: current status. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2011;13:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishina K., Piao W., Yoshida-Tanaka K., Sujino Y., Nishina T., Yamamoto T., Nitta K., Yoshioka K., Kuwahara H., Yasuhara H. DNA/RNA heteroduplex oligonucleotide for highly efficient gene silencing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7969. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohhashi S., Ohuchida K., Mizumoto K., Fujita H., Egami T., Yu J., Toma H., Sadatomi S., Nagai E., Tanaka M. Down-regulation of deoxycytidine kinase enhances acquired resistance to gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(4B):2205–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumagai M., Shimoda S., Wakabayashi R., Kunisawa Y., Ishii T., Osada K., Itaka K., Nishiyama N., Kataoka K., Nakano K. Effective transgene expression without toxicity by intraperitoneal administration of PEG-detachable polyplex micelles in mice with peritoneal dissemination. J. Control. Release. 2012;160:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.