Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the present study is to study what is the best predictor of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) in IVF.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of all consecutive IVF/intracytoplasmic injection cycles performed during a 5-year period (2009–2014) in a single university fertility centre. All fresh IVF cycles where ovarian stimulation was performed with gonadotrophins and GnRH agonists or antagonists and triggering of final oocyte maturation was induced with the administration of urinary or recombinant hCG were analyzed (2982 patients undergoing 5493 cycles). Because some patients contributed more than one cycle, the analysis of the data was performed with the use of generalized estimating equation (GEE).

Results

Severe OHSS was diagnosed in 20 cycles (0.36%, 95% CI 0.20–0.52). The number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of triggering final oocyte maturation represents the best predictor of severe OHSS in IVF cycles. The cutoff in the number of follicles ≥10 mm with the best capacity to discriminate between women that will and will not develop severe OHSS was ≥15.

Conclusion

The presence of more than 15 follicles ≥10 mm on the day of triggering final oocyte maturation represents the best predictor of severe OHSS in IVF cycles.

Keywords: OHSS, IVF, Prediction, Prevention, Number of follicles

Introduction

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a serious iatrogenic complication of ovarian stimulation treatments for in vitro fertilization (IVF). According to the 2010 report of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in Europe by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), it has a prevalence of 0.3% of IVF cycles [1]. Although the incidence of OHSS is low and tends to decrease in recent years [1–4], the fact that subfertile women pursuing pregnancy by ART might experience a potentially lethal iatrogenic complication [5, 6] renders OHSS as one of the most important concerns of modern IVF practice.

The pathophysiology of OHSS is not fully understood, yet it is believed that a combination of factors such as genetic susceptibility [7, 8], ovarian hyperstimulation, and mainly the presence of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) initiate in some patients a cascade of events that involve increased production and activity of vasoactive substances. hCG is thought to play a crucial role in the development of the syndrome as severe forms are restricted to cycles with exogenous hCG (to induce ovulation or as luteal phase support) or with endogenous pregnancy-derived hCG [9]. Actually, two conditions appear to be a prerequisite to the development of the syndrome: multiple follicular growth and further extensive luteinization of these follicles. The syndrome is indeed exclusively postovulatory and is the consequence of a large production of vasoactive ovarian factor(s) such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), various interleukins, and angiotensin during the formation of the multiple corpora lutea [9–14].

This imbalance of vasoactive substances results in altered vascular permeability of mesothelial surfaces, inducing a vascular fluid leakage, which is the main physiological basis of the clinical symptoms of OHSS.

OHSS can have early or late onset. Early OHSS is an acute consequence of the exogenous hCG administration before oocyte retrieval in IVF cycles and is usually related to an excessive ovarian response to gonadotrophin stimulation. Late OHSS is induced by endogenous hCG produced from the starting pregnancy and is observed in women who become pregnant [15, 16]. Although hCG is administered in most IVF cycles for triggering final oocyte maturation, OHSS happens only rarely [2, 3] and it has been shown that the magnitude of ovarian response is well correlated with the risk of OHSS [17, 18].

Several strategies have been developed for the prevention of severe OHSS including cycle cancellation [19], coasting [20], decrease in the dose of hCG administration [21], cryopreservation of all embryos [22, 23], use of macromolecules such as albumin [24] or hydroxyethyl starch [25], and administration of cabergoline [26]. The development of GnRH antagonist protocols has rendered possible the triggering of ovulation with endogenous LH surge instead of hCG, which appeared to be associated with a decreased incidence of OHSS [27]. This was achieved through the administration of GnRH agonist [28] or more recently through the injection of kisspeptin-54 [29]. The increased acceptance of the GnRH antagonist protocol and the introduction of vitrification for embryo cryopreservation have rendered an alternative strategy, the administration of GnRH agonists for triggering final oocyte maturation combined with cryopreservation of all embryos, for transfer in subsequent frozen-thawed cycles [30] quite popular. This strategy seems to be quite effective, since severe OHSS occurrence following agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation has been limited in a small number of case reports [31–33]. In order to further decrease OHSS risk, it was recently proposed to administer gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist during the luteal phase [34, 35].

It should be noted that the use of the above strategies is meaningful when the risk of severe OHSS is particularly elevated and can be quantified prior to triggering of final oocyte maturation. The identification of prediction factors is therefore crucial.

So far, several attempts have been made to predict severe OHSS. Considering that the occurrence of the syndrome is largely correlated with the response of the ovaries to stimulation, indices of ovarian response have been used for this purpose. The level of estradiol, the number of follicles on the day of triggering final oocyte maturation, the number of oocytes retrieved, the total dose of gonadotrophins, and the duration of stimulation have been evaluated as predictors of severe OHSS occurrence with conflicting, however, results regarding their potential as single predictors of severe OHSS [2, 17, 36–38].

The aim of this study was to identify the best single predictor of severe OHSS in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF with gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues by analyzing a large number of IVF cycles from a single center.

Materials and methods

Population

In this retrospective cohort study, the IVF cycles of 5 years of practice (March 2009–February 2014) from the Fertility Clinic of the Erasme Hospital of the French-speaking Free University of Brussels were reviewed. All fresh IVF cycles where ovarian stimulation was performed with gonadotrophins and GnRH agonists or antagonists and triggering of final oocyte maturation was induced with the administration of urinary or recombinant hCG were analyzed (2982 patients undergoing 5493 cycles). Oocyte donation cycles as well as those cycles in which hCG was administered during the luteal phase were excluded. Furthermore, cycles where coasting was performed in order to prevent OHSS were excluded from the present study. No other forms of OHSS prevention (e.g., albumin, cabergoline administration) were utilized during the study period.

Ovarian stimulation

Ovarian stimulation was performed with the use of daily gonadotrophins, and prevention of LH surge was accomplished with the administration of GnRH analogues. Starting dose was determined by the treating physician on the basis of age, basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), body mass index (BMI), and previous response to ovarian stimulation (range 75–300). Anti-mullerian (AMH) hormone was also used for this purpose in some patients since 2008, although its assessment became more systematic after 2011. Ovarian stimulation was monitored by transvaginal ultrasonography and assessment of estradiol and LH as required.

As soon as the criteria for final oocyte maturation were met (presence of three or more follicles ≥17 mm) either urinary (10,000 IU) or recombinant (250 μg) hCG was used to trigger final oocyte maturation. Oocyte retrieval was performed 36–38 h after hCG administration and embryos were fertilized either with conventional IVF or intracytoplasmic injection (ICSI). One to four embryos (mean ± standard deviation (SD) 1.4 ± 0.8) were transferred 2–5 days after fertilization depending on the age of the patient, the score of the embryos, and the number of previous trials. All women received micronized progesterone as luteal support.

Diagnosis and classification of OHSS

The primary outcome measure was occurrence of severe OHSS, while occurrence of moderate OHSS was considered as a secondary outcome measure. OHSS was assessed based on the criteria of Golan et al. [39]. Hence, moderate OHSS was diagnosed in patients with abdominal distension, discomfort associated or not with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, enlarged ovaries, and ultrasonographic evidence of ascites. Patients with severe OHSS were those who also had clinical evidence of ascites and/or hydrothorax, breathing difficulties or hemoconcentration, increased blood viscosity, and decreased renal perfusion [5]. All patients with severe OHSS were hospitalized, and supportive measures were taken until their clinical status was improved. Cases of moderate OHSS were monitored on an outpatient basis. If a patient was initially diagnosed with moderate OHSS but was subsequently diagnosed with severe OHSS with requirement for hospitalization, she was registered as a severe OHSS case. Patients that were diagnosed within 9 days after oocyte retrieval were classified as early-onset OHSS cases and those who were diagnosed after the first 9 days as late-onset OHSS cases [15, 16].

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) or as median (interquartile range (IQR)) depending on the normality of their distribution, which was evaluated by inspection of distribution plots and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Because some patients contributed more than one cycle, the analysis of the data was performed with the use of generalized estimating equation (GEE), which is an extension of the generalized linear model framework and accounts for any auto-correlation (clustering effect) between the data. Logit regression models were constructed in order to extract results regarding potential associations between predictors and dependent variables.

Using the results from the aforementioned GEE models, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed on significant predictors and areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated along with their binomial confidence intervals in order to identify the variable that could better discriminate between patients with and without severe OHSS. The optimal criterion for each ROC analysis was identified according to Youden’s index [40].

Multivariable GEE regression analyses were also performed in order to explore the possibility of constructing a combined model that could predict severe OHSS more efficiently than a model based on a single predictor.

Due to the retrospective nature of the data, not all cases in the database had complete records for every independent variable examined. All analyses were performed on the basis of a complete dataset. In bivariate logistic regression analyses, all evaluable cases (non-missing) for each variable were utilized. In multivariable regression analyses, all cases with non-missing data for all of the predictors were used. To check for the robustness of these results, all bivariate analyses were also performed on the basis of a complete-record dataset defined as these cases where data about follicles on the day of hCG, E2 levels on the day of hCG, and total FSH dose were available.

Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Stata (ver. 13.1 for Mac) and MedCalc (ver. 13.0). All statistical tests were two-sided, and alpha error was set at 0.05.

Results

In total, 2982 patients were stimulated with daily gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues and triggered with hCG with the intention to perform a fresh embryo transfer using own oocytes in 5493 cycles. In 2653 of these cycles, GnRH agonists were used for preventing premature LH surge, while in 2840 cycles, GnRH antagonists were used for the same purpose. Stimulation was performed with menotropins (n = 2289 cycles, 41.7%), urofollitropins (n = 15 cycles, 0.2%), or recombinant (n = 3189, 58.1%) FSH. Triggering of final oocyte maturation was performed in the majority of cases with 10,000 IU urinary hCG (n = 5331 cycles, 97.1%) while in 162 cycles (2.9%), 250 μg recombinant hCG was used. Embryo transfer was performed in 4824 cycles (87.8%), out of which 1874 had a positive pregnancy test (38.8% per ET) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cycle

| Parametera | Estimates |

|---|---|

| Female age (years) | 35.0 (5.2) |

| Total dose of FSH (IU) | 2135 (840) |

| Duration of stimulation (days) | 10.3 (2.6) |

| E2 on the day of hCG (pg/mL) | 1768 (919) |

| Follicles <10 mm | 2.0 (3.8) |

| Follicles 10–14 mm | 3.4 (3.4) |

| Follicles 15–30 mm | 6.1 (3.6) |

| Total follicles | 11.5 (7.2) |

| Type of trigger | uhCG 5331 (97.1%), rhCG 162 (2.9%) |

| Cumulus oocyte complexes retrieved | 7.0 (4.8) |

| Type of fertilization | IVF 2133 (38.8%), ICSI 3360 (61.2%) |

| Number of cycles with embryo transfer | 4824 (87.8%) |

| Number of embryos transferred | 1.4 (0.8) |

| Number of embryos cryopreserved | 0.7 (1.6) |

| Cycles with positive pregnancy test | 1874 |

| Pregnancy rate per cycle (%) (95% CI) | 34.1 (32.9–35.4) |

| Pregnancy rate per patientb (%) (95% CI) | 35.0 (33.7–36.4) |

| Pregnancy rate per ET (%) (95% CI) | 38.8 (37.5–40.2) |

| Pregnancy rate per ET per patientb (%) (95% CI) | 39.8 (38.4–41.3) |

aData are presented as mean (standard deviation) or n (%)

bEstimates produced through generalized estimating equation (GEE) modeling which adjusts for auto-correlation of cycles

OHSS occurrence

Moderate OHSS occurred in 74 cycles (1.35%), and severe OHSS was diagnosed in 20 cycles (0.36%). Adjusting for the clustered form of data did not result in substantially different estimates of the OHSS risk (Table 2). Moderate and severe OHSSs were diagnosed in average at 11.6 and 10.8 days, respectively, after OPU. Overall, 30 cases had early moderate OHSS (40.5% of all moderate OHSS cases), while severe OHSS was more frequently diagnosed as a late severe OHSS (65.0%).

Table 2.

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome occurrence and characteristics

| Severity of OHSS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Severe | Total | |

| Occurrence of OHSS | |||

| n | 74 | 20 | 94 |

| Unadjusted risk (%) (95% CI) | 1.35% (1.04–1.65) | 0.36% (0.20–0.52) | 1.71% (1.37–2.05) |

| Adjusted riska (%) (95% CI) | 1.36% (1.05–1.67) | 0.38% (0.20–0.55) | 1.77% (1.42–2.13) |

| Time of OHSS diagnosis (days after oocyte retrieval) mean (SD) | 11.6 (7.0) | 10.8 (5.1) | 11.4 (6.6) |

| Type of OHSS | |||

| Early | 30 | 7 | 37 |

| Late | 44 | 13 | 57 |

aAdjusted risk produced through generalized estimating equation (GEE) modeling which adjusts for auto-correlation of data

Most patients with moderate (53/74, 71.6%) and severe (16/20, 80.0%) OHSSs had a positive pregnancy test. Only three cases with a negative pregnancy test had a late moderate OHSS. Regarding severe OHSS, all of the patients that were diagnosed with a late severe OHSS had a positive pregnancy test.

Predicting severe OHSS on the day of hCG

The characteristics of cycles with and those without severe OHSS are presented and compared in Table 3. Based on these results, the pre-hCG characteristics that were significantly different between these two groups were (a) the total dose of FSH required to complete stimulation, (b) the E2 levels on the day of hCG, and (c) the total number of follicles 10–14 and 15–30 mm (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between cycles with or without severe OHSS

| Parametera | Cycles with severe OHSS n = 20 | Cycles without severe OHSS N = 5473 | P b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female age (years)a | 34.4 | 34.6 | 0.531 |

| Total dose of FSH (IU)a | 1707 | 2103 | <0.001 |

| Type of GnRH analogue usedb | Agonist 8 Antagonist 12 |

Agonist 2645 Antagonist 2828 |

0.483 |

| Duration of stimulation (days)a | 10.3 | 10.3 | 0.937 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (pg/mL)a | 2855 | 1844 | <0.001 |

| Follicles <10 mma | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.552 |

| Follicles 10–14 mma | 7.4 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Follicles 15–30 mma | 11.7 | 6.3 | <0.001 |

| Type of triggerb | uhCG 19 rhCG 1 |

uhCG 5312 rhCG 161 |

0.562 |

| Cumulus oocyte complexes retrieveda | 13.4 | 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Type of fertilizationb | IVF 8 ICSI 12 |

IVF 2125 ICSI 3348 |

0.847 |

| Number of cycles with embryo transferb | 20 | 4804 | n.e. |

| Number of embryos transferreda | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.728 |

| Number of embryos cryopreserveda | 2.4 | 0.8 | 0.027 |

| Cycles with positive pregnancy test | 16 | 1858 | <0.001 |

n.e. not estimable

aContinuous variables are presented as means that have been calculated after adjusting for the auto-correlation of data

bAll p values have been calculated while adjusting for the auto-correlation of data

Single predictors/bivariate logistic regression analyses

Bivariate logistic regression analyses (using the GEE framework) indicated that all three aforementioned variables were significant predictors of severe OHSS occurrence (Table 4). For every additional follicle ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, an 18% relative increase in the risk of severe OHSS was noted. Similarly, for every 1000 pg/mL increase in the E2 concentration on the day of hCG, the risk of severe OHSS was increased by 180%. On the other hand, for every additional 1000 IUs of FSH, the risk of severe OHSS was reduced by 79% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prediction of severe OHSS

| Predictor | Sample size | OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single predictors | ||||||||

| Follicles ≥10 mm* | 5181 | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | 0.904 (0.895–0.912) | ≥15 | 89.5 (74.0–99.0) | 82.9 (80.6–82.7) | 5.19 | 0.13 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (per 1000 pg/mL) | 5425 | 2.80 (1.80–4.37) | 0.790 (0.779–0.801) | ≥2.201 | 85.0 (62.1–96.8) | 71.8 (70.5–72.9) | 3.01 | 0.21 |

| Total dose of FSH (per 1000 IU) | 5488 | 0.21 (0.11–0.43) | 0.763 (0.751–0.774) | ≤1.700 | 85.0 (62.1–96.8) | 64.2 (62.9–65.5) | 2.37 | 0.23 |

| Follicles and E2 on the day of hCG and total FSH dose model* | ||||||||

| Follicles ≥10 mm | 5156 | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) | 0.916 (0.908–0.923) | >0.0054 | 84.2 (60.4–96.6) | 85.9 (84.9–86.9) | 5.98 | 0.18 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.89 (0.93–3.83) | |||||||

| Total dose of FSH (per 1000 IU) | 0.30 (0.11–0.82) | |||||||

*No significant difference between the models with follicles ≥10 mm vs. combined model (AUC diff 0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.06; p = 0.641)

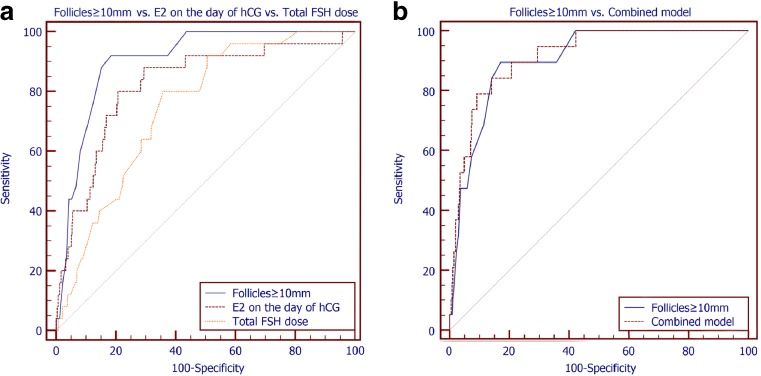

The capacity of these variables to discriminate between patients with or without severe OHSS was also assessed through ROC analyses (Fig. 1a). The number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG exhibited the largest area under the curve (AUC = 0.904, 95% CI 0.895–0.912), although this AUC was significantly different only when compared with the AUC of the total FSH dose (AUC diff +0.136, 95% CI 0.039–0.234). When compared with the AUC of the E2 on the day of hCG, no significant difference could be detected (AUC diff +0.111, 95% CI −0.005 to +0.227). Similarly, no difference was noted between the AUC of the E2 on the day of hCG and the total dose of FSH (AUC diff 0.025, 95% CI −0.107 to +0.157) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

a Receiver operator characteristic analyses of the ability of the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, the E2 levels on the day of hCG, and the total FSH dose to predict the occurrence of severe OHSS. b Receiver operator characteristic analyses of the ability of the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG and of the combined GEE model including the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, the E2 levels on the day of hCG, and the total FSH dose to predict the occurrence of severe OHSS

The cutoff in the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG with the best capacity to discriminate between women that will and will not develop severe OHSS was ≥15 (Table 4). More specifically, having ≥15 follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG translated in a substantially increased risk of severe OHSS as compared to having <15 follicles (OR 28.7, 95% CI 8.5–97.1). This cutoff was also able to identify 89.5% of cases of severe OHSS and also to correctly classify as not at risk for severe OHSS 82.9% of women that did not experience severe OHSS. Given the prevalence of severe OHSS in this population (0.36%) (Table 2), the positive predictive value of this cutoff is 1.86%, while the negative predictive value is 99.95%.

Regarding E2 levels on the day of hCG, the best cutoff identified was 2201 pg/mL (Table 4). Having a serum concentration of E2 on the day of hCG equal or more than 2201 pg/mL increases the odds of severe OHSS by 13.2 times (OR 13.2, 95% CI 3.9–44.8). This cutoff identified 85.0% of the cases of severe OHSS and also correctly classified as not being at risk for severe OHSS 71.8% of cases where severe OHSS did not develop. Given the prevalence of severe OHSS in this population (Table 2), the positive predictive value is 1.08%, while the negative predictive value is 99.92%.

Completing ovarian stimulation with a total dose of FSH equal or less than 1700 IU was the best cutoff for the detection of women at high risk for severe OHSS (Table 4). By using this threshold, 85.0% of the cases of severe OHSS were identified and 64.2% of women not diagnosed with severe OHSS were correctly classified. Considering the prevalence of severe OHSS in this population (Table 2), the positive predictive value is 0.85%, while the negative predictive value is 99.92%.

Combined model of predictors/multivariable logistic regression analyses

Subsequently, the three aforementioned variables were included in the same model, aiming to produce a model with improved characteristics. The combined model had a larger AUC than the one of the total number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG (Table 4); however, this difference was not significant (AUC diff +0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to +0.06) (Fig. 1b). The optimal threshold identified for the combined model (expressed as a score) had higher specificity (85.9%), at the expense of lower sensitivity (84.2%) when compared to the total number of follicles ≥10 mm (Table 4). Considering the prevalence of severe OHSS in this population (Table 2), the positive predictive value of using this method is 2.11%, while the negative predictive value is 99.93%.

Sensitivity analyses

Complete-record cases

Restricting the analyses only in the complete-record cases (those cycles where information about all three variables was available, n = 5120) did not substantially alter the conclusions drawn (Table 5). The total number of follicles ≥10 mm had the largest AUC, and the optimal threshold to discriminate between cycles with or without severe OHSS was still ≥15.

Table 5.

Prediction of severe OHSS (complete-record analysis)

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity(95% CI) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single predictors | |||||||

| Follicles ≥10 mm | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | 0.904 (0.895–0.912) | ≥15 | 89.5 (66.9–98.7) | 64.2 (62.9–65.5) | 5.22 | 0.13 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (per 1000 pg/mL) | 2.88 (1.80–4.58) | 0.790 (0.779–0.801) | ≥2.210 | 85.0 (62.1–96.8) | 71.8 (70.5–72.9) | 3.01 | 0.21 |

| Total dose of FSH (per 1000 IU) | 0.20 (0.09–0.42) | 0.763 (0.751–0.774) | ≤1.700 | 85.0 (62.1–96.8) | 64.2 (62.9–65.5) | 2.37 | 0.23 |

Type of GnRH analogue

Repeating the analysis separately for cycles where GnRH agonists and GnRH antagonists were used did not materially change the conclusions of the main analysis. The total number of follicles ≥10 mm remained the predictor with the best performance. Notably, although in GnRH antagonist cycles, the optimal cutoff for identification of cases at high risk for severe OHSS was still ≥15 follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, in the GnRH agonist cycles, this cutoff was ≥16.

Other predictors of high ovarian response

Including the value of AMH in the same model, the total number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG for the 3074 cycles (n = 1770 women) for which this information was available did not improve the predictive ability of the model. The value of serum anti-mullerian hormone was not significantly associated with the occurrence of severe OHSS when an adjustment was made for the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG trigger (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.74–1.08). Similarly, a diagnosis of PCOS (n = 552) was also not significantly associated with the occurrence of severe OHSS, when the total number of follicles ≥10 mm was controlled for (OR 1.63, 95% CI 0.27–9.99).

Predicting moderate OHSS on the day of hCG

The performance of the single predictors and the combined model to predict the occurrence of moderate OHSS is depicted in Table 6. Overall, the discriminatory capacity of these variables to predict moderate OHSS was lower as compared to their capacity to predict the occurrence of severe OHSS. The total number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG had a significantly larger AUC as compared to E2 on the day of hCG and the total FSH dose (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, this AUC was not significantly different from the AUC of the combined model (AUC diff −0.007, 95% CI −0.022 to +0.006) (Fig. 2b).

Table 6.

Prediction of moderate OHSS

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single predictors | |||||||

| Follicles ≥10 mm* | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | 0.787 (0.775–0.798) | ≥12 | 74.7 (62.9–84.2) | 70.4 (69.1–71.6) | 2.52 | 0.36 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.80 (1.50–2.15) | 0.691 (0.678–0.703) | ≥1.540 | 85.1 (75.0–92.3) | 47.4 (46.0–48.7) | 1.62 | 0.31 |

| Total dose of FSH (per 1000 IU) | 0.53 (0.38–0.75) | 0.635 (0.622–0.648) | ≤1.700 | 59.5 (47.4–70.7) | 64.5 (63.2–65.8) | 1.67 | 0.63 |

| Follicles and E2 on the day of hCG and total FSH dose model* | |||||||

| Follicles ≥10 mm | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 0.796 (0.785–0.807) | >0.0127 | 80.3 (69.1–88.8) | 69.7 (68.4–70.9) | 2.65 | 0.28 |

| E2 on the day of hCG (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.16 (0.88–1.52) | ||||||

| Total dose of FSH (per 1000 IU) | 0.75 (0.52–1.08) | ||||||

*No significant difference between the models with Follicles ≥10mm vs. Combined model (AUC diff: 0.010, 95% CI: -0.006 to 0.025; p = 0.231)

Fig. 2.

a Receiver operator characteristic analyses of the ability of the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, the E2 levels on the day of hCG, and the total FSH dose to predict the occurrence of moderate OHSS. b Receiver operator characteristic analyses of the ability of the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG and of the combined GEE model including the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG, the E2 levels on the day of hCG, and the total FSH dose to predict the occurrence of moderate OHSS

Discussion

This study supports that the best predictor of severe OHSS, in IVF cycles where stimulation has been performed with daily gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues, is the total number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG administration. A combined model including the number of follicles ≥10 mm, E2 levels on the day of hCG, and the total dose of FSH did not improve significantly the predictive ability of the model. A cutoff of ≥15 follicles ≥10 mm appears to offer the overall best performance and is associated with high sensitivity and specificity for the identification of severe OHSS. Moderate OHSS occurrence can be identified using a cutoff of ≥12 follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG although the sensitivity and specificity are not as high as those observed for severe OHSS prediction.

The issue of predicting OHSS has been evaluated in the past [18, 41–45] although not as frequently as one would expect considering the importance and the clinical implications of OHSS. Efforts have been made to identify patients at risk of OHSS prior to initiation of stimulation [44–49]. However, it is clear that since OHSS is closely linked with ovarian response to stimulation, prediction of OHSS becomes more reliable when ovarian stimulation has been completed and the ovarian response is known. It is at this time that prediction of severe OHSS is also clinically useful since important measures can be applied to reduce OHSS risk. The current study emphasized on these two important aspects in order to provide clinicians with a more reliable prediction of severe OHSS at a time where they can choose to either reduce the dose of hCG or use GnRH agonist for triggering final oocyte maturation (in GnRH antagonist cycles) or apply other preventive measures (e.g., administration of cabergoline from the day of hCG).

This study seems to be in agreement with previous reports that have also identified the number of follicles on the day of hCG as a consistent predictor of severe OHSS [2, 41, 47, 50, 51]. Moreover, in the study by Papanikolaou et al. [2], it was also suggested that the number of follicles ≥11 mm had significantly larger AUC as compared to the E2 levels on the day of hCG. The identified cutoff in that study was ≥18 follicles ≥11-mm follicles, which is comparable to the one identified in the current study (≥15 follicles ≥10 mm).

It should be noted that the risk for severe OHSS (adjusted risk 0.36%) is lower than what has been reported previously. This discrepancy might reflect the different diagnostic criteria used between studies, differences in the populations analyzed, or more importantly differences in the ovarian stimulation strategy. In the study by Papanikolaou et al. [2], the incidence of severe OHSS was 2.1%. However, it should be noted that the mean number of oocytes retrieved in that study (OHSS 21.3; non-OHSS 11.0) [2] was substantially higher than the one in the current study (OHSS 13.4; non-OHSS 7.2) (Table 3), which might have accounted for the difference in the incidence of severe OHSS. This is in agreement with a prevalence of OHSS of 0.3% IVF cycles in the last report of ART in Europe by ESHRE [1] and the decreased incidence of the syndrome during recent years [1].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study that investigates potential pre-ovulatory predictors of severe OHSS in ovarian stimulation for IVF. Furthermore, it provides data from a relatively recent time period, and hence, it is likely to reflect more accurately current practice. This study includes data from a single center, which increases the homogeneity of the population in terms of ovarian stimulation and especially in terms of diagnosis of OHSS using a single definition. Moreover, the data have been analyzed while accounting for the non-independence of data and this strengthens the validity of the conclusions drawn.

This study is also characterized by some limitations. The retrospective nature of this study renders it potentially vulnerable to multiple sources of bias. Most importantly, the diagnosis of OHSS is an area where significant variability can be present. Although a single definition was used throughout the study period, and the main outcome measure (i.e., severe OHSS) included hospitalization, which is a more robust indicator, potential misclassification of OHSS cases cannot be excluded. Furthermore, due to the retrospective nature of this study, not all cases had information about the three main predictors. However, a sensitivity analysis including only complete-record cases (Table 5) did not materially change the results obtained. The present study also included both GnRH agonist and antagonist cycles. A sensitivity analysis performed in GnRH agonist or antagonist cycles confirmed the main finding, i.e., that the total number of follicles ≥10 mm is the best predictor of severe OHSS. In the same sensitivity analysis though, it was noted that the optimal cutoff in GnRH agonist cycles is ≥16 follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG whereas for GnRH antagonist cycles, the proposed cutoff is ≥15 follicles ≥10 mm. The triggering of final oocyte maturation was performed in all cycles using either 10,000 IU urinary hCG or 250 μg recombinant hCG. Therefore, our data cannot be applied in cycles where final oocyte maturation is performed with lower doses of hCG or GnRH agonists.

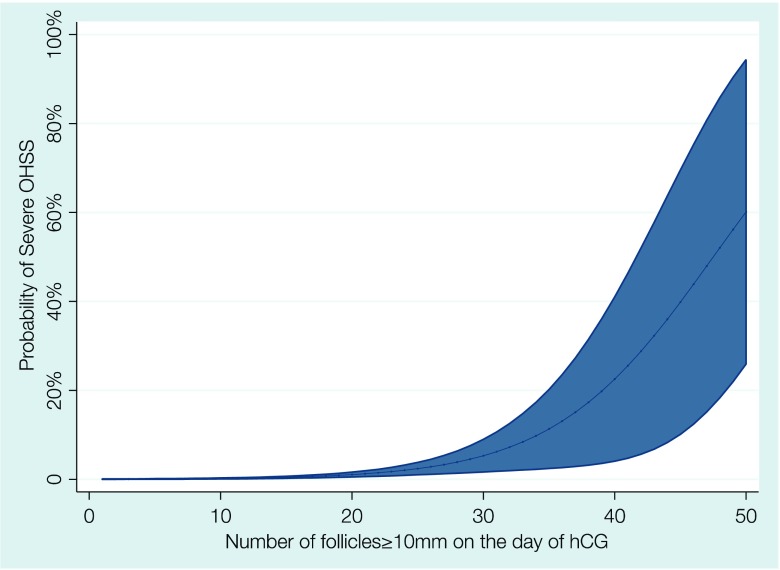

The findings from this study can provide a simple and effective way of identifying patients at high risk for severe OHSS. The number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG appears to be the best predictor and a graphical representation of the probability of severe OHSS occurrence as a function of the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG is presented in Fig. 3. Using a cutoff of ≥15 follicles ≥10 mm allows for the identification of 89.5% of severe OHSS cases. Using the prevalence of severe OHSS that was observed in this study, the presence of <15 follicles ≥10 mm means that the chance of severe OHSS in that cycle is reduced to 0.05% (5/10,000 cycles). However, in only 1.86% of those cycles, identified as at risk for severe OHSS (≥15 follicles ≥10 mm), the syndrome will actually develop.

Fig. 3.

Association between number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG and the probability of severe OHSS (shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals)

In conclusion, the number of follicles ≥10 mm on the day of hCG seems to be the best predictor of severe OHSS after ovarian stimulation with gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues for IVF. Using, a threshold of 15 follicles allows for the identification of patients with particularly increased risk where preventive measures should be taken.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (P2014/210).

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.Kupka MS, Ferraretti AP, de Mouzon J, Erb K, D’Hooghe T, Castilla JA, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2010: results generated from European registers by ESHRE†. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2099–2113. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papanikolaou EG, Pozzobon C, Kolibianakis EM, Camus M, Tournaye H, Fatemi HM, et al. Incidence and prediction of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in women undergoing gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2005;85:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smitz J, Camus M, Devroey P, Erard P, Wisanto A, Van Steirteghem AC. Incidence of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after GnRH agonist/HMG superovulation for in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1990;5:933–937. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarlatzis BC, Griesinger G, Leader A, Rombauts L, Ijzerman-Boon PC, BMJL M. Comparative incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following ovarian stimulation with corifollitropin alfa or recombinant FSH. Reprod BioMed Online. 2012;24:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: classifications and critical analysis of preventive measures. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:275–289. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navot D, Bergh PA, Laufer N. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in novel reproductive technologies: prevention and treatment. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:249–261. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)55188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delbaere A, Smits G, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Genetic predictors of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:590–591. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daelemans C, Smits G, de Maertelaer V, Costagliola S, Englert Y, Vassart G, et al. Prediction of severity of symptoms in iatrogenic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by follicle-stimulating hormone receptor Ser680Asn polymorphism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6310–6315. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delbaere A, Smits G, De Leener A, Costagliola S, Vassart G. Understanding ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Endocrine. 2005;26:285–290. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:26:3:285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI. Pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:449–451. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)55459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delbaere A, Bergmann PJ, Gervy-Decoster C, Staroukine M, Englert Y. Angiotensin II immunoreactivity is elevated in ascites during severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: implications for pathophysiology and clinical management. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:731–737. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delbaere A, Bergmann PJ, Gervy-Decoster C, Camus M, de Maertelaer V, Englert Y. Prorenin and active renin concentrations in plasma and ascites during severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:236–240. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delbaere A, Smits G, Olatunbosun O, Pierson R, Vassart G, Costagliola S. New insights into the pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. What makes the difference between spontaneous and iatrogenic syndrome? Hum Reprod. 2004;19:486–489. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evbuomwan I. The role of osmoregulation in the pathophysiology and management of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2013;16:162–167. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.831996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyons CA, Wheeler CA, Frishman GN, Hackett RJ, Seifer DB, Haning RV. Early and late presentation of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: two distinct entities with different risk factors. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:792–799. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur RS, Akande AV, Keay SD, Hunt LP, Jenkins JM. Distinction between early and late ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:901–907. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aboulghar M. Prediction of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Estradiol level has an important role in the prediction of OHSS. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1140–1141. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris RS, Paulson RJ, Sauer MV, Lobo RA. Predictive value of serum oestradiol concentrations and oocyte number in severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:811–814. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balen AH, Braat D, West C, Patel A, Jacobs HS. Cumulative conception and live birth rates after the treatment of anovulatory infertility: safety and efficacy of ovulation induction in 200 patients. Hum Reprod. 1994; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.D’Angelo A, Brown J, Amso NN. Coasting (withholding gonadotrophins) for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;:CD002811. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kashyap S, Parker K, Cedars MI, Rosenwaks Z. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome prevention strategies: reducing the human chorionic gonadotropin trigger dose. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:475–485. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada I, Matson PL, Horne G, Buck P, Lieberman BA. Is continuation of a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) necessary for women at risk of developing the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome? Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1090–1093. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salat-Baroux J, Alvarez S, Antoine JM, Cornet D. Treatment of hyperstimulation during in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. Oxford University Press; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Venetis CA, Kolibianakis EM, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Papadimas I, Tarlatzis BC. Intravenous albumin administration for the prevention of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95:188–96–196.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graf MA, Fischer R, Naether OG, Baukloh V, Tafel J, Nückel M. Reduced incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by prophylactic infusion of hydroxyaethyl starch solution in an in-vitro fertilization programme. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2599–2602. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.12.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang H, Hunter T, Hu Y, Zhai S-D, Sheng X, Hart RJ. Cabergoline for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008605–5. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008605.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humaidan P, Papanikolaou EG, Tarlatzis BC. GnRHa to trigger final oocyte maturation: a time to reconsider. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2389–2394. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fauser BC, de Jong D, Olivennes F, Wramsby H, Tay C, Itskovitz-Eldor J, et al. Endocrine profiles after triggering of final oocyte maturation with GnRH agonist after cotreatment with the GnRH antagonist ganirelix during ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:709–715. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbara A, Jayasena CN, Christopoulos G, Narayanaswamy S, Izzi-Engbeaya C, Nijher GMK, et al. Efficacy of kisspeptin-54 to trigger oocyte maturation in women at high risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) during in vitro fertilization (IVF) therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3322–3331. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griesinger G, Schultz L, Bauer T, Broessner A. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome prevention by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation in a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol in combination with a “freeze-all” strategy: a prospective multicentric study. Fertil. Steril. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Fatemi HM, Popovic-Todorovic B, Humaidan P, Kol S, Banker M, Devroey P, et al. Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist trigger and “freeze-all” approach in GnRH antagonist protocol. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1008–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurbuz AS, Gode F, Ozcimen N, Isik AZ. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist trigger and freeze-all strategy does not prevent severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a report of three cases. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;29:541–544. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling LP, Phoon JWL, Lau MSK, Chan JKY, Viardot-Foucault V, Tan TY, et al. GnRH agonist trigger and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: relook at ‘freeze-all strategy’. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;29:392–394. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lainas GT, Kolibianakis EM, Sfontouris IA, Zorzovilis IZ, Petsas GK, Lainas TG, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels following luteal gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist administration in women with severe early ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. BJOG. 2014;121:848–855. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lainas TG, Sfontouris IA, Zorzovilis IZ, Petsas GK, Lainas GT, Kolibianakis EM. Management of severe early ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by re-initiation of GnRH antagonist. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;15:408–412. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CD, Wu MY, Chao KH, Chen SU, Ho HN, Yang YS. Serum estradiol level and oocyte number in predicting severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 1997;96:829–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Angelo A, Davies R, Salah E, Nix BA, Amso NN. Value of the serum estradiol level for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a retrospective case control study. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steward RG, Lan L, Shah AA, Yeh JS, Price TM, Goldfarb JM, et al. Oocyte number as a predictor for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and live birth: an analysis of 256,381 in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golan A, Ron-El R, Herman A. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: an update review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1949;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blankstein J, Shalev J, Saadon T, Kukia EE, Rabinovici J, Pariente C, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: prediction by number and size of preovulatory ovarian follicles. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delvigne A, Vandromme J, Barlow P, Lejeune B, Leroy F. Are there predictive criteria of complicated ovarian hyperstimulation in IVF? Hum Reprod. 1991;6:959–962. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiedler K, Ezcurra D. Predicting and preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): the need for individualized not standardized treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:32-2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navot D, Relou A, Birkenfeld A, Rabinowitz R, Brzezinski A, Margalioth EJ. Risk factors and prognostic variables in the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:210–215. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ocal P, Sahmay S, Cetin M, Irez T, Guralp O, Cepni I. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count as predictive markers of OHSS in ART cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:1197–1203. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9627-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bódis J, Török A, Tinneberg HR. LH/FSH ratio as a predictor of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:869–870. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.4.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danninger B, Brunner M, Obruca A, Feichtinger W. Prediction of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by ultrasound volumetric assessment [corrected] of baseline ovarian volume prior to stimulation. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1597–1599. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gustafson O, Carlström K, Nylund L. Androstenedione as a predictor of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:918–921. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee T-H, Liu C-H, Huang C-C, Wu Y-L, Shih Y-T, Ho H-N, et al. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone and estradiol levels as predictors of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in assisted reproduction technology cycles. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:160–167. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aramwit P, Pruksananonda K, Kasettratat N, Jammeechai K. Risk factors for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in Thai patients using gonadotropins for in vitro fertilization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1148–1153. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Enskog A, Henriksson M, Unander M, Nilsson L, Brännström M. Prospective study of the clinical and laboratory parameters of patients in whom ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome developed during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:808–814. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]