Abstract

Purpose

Emergency department assessment represents a critical but often missed opportunity to identify elder abuse, which is common and has serious consequences. Among emergency care providers, diagnostic radiologists are optimally positioned to raise suspicion for mistreatment when reviewing imaging of geriatric injury victims. However, little literature exists describing relevant injury patterns, and most radiologists currently receive neither formal nor informal training in elder abuse identification.

Methods

We present 2 cases to begin characterisation of the radiographic findings in elder abuse.

Results

Findings from these cases demonstrate similarities to suspicious findings in child abuse including high-energy fractures that are inconsistent with reported mechanisms and the coexistence of acute and chronic injuries. Specific injuries uncommon to accidental injury are also noted, including a distal ulnar diaphyseal fracture.

Conclusions

We hope to raise awareness of elder abuse among diagnostic radiologists to encourage future large-scale research, increased focus on chronic osseous findings, and the addition of elder abuse to differential diagnoses.

Keywords: Elder abuse, Elder abuse radiology findings, Geriatric injury, Intentional injury

Elder abuse is common and has serious consequences, but it is under-recognized. As many as 10% of U.S. older adults experience elder mistreatment each year [1,2], and evidence suggests that victims have dramatically increased mortality and morbidity [3]. Elder mistreatment involves a trusting relationship between an older person and another individual in which the trust has been violated in some way [1]. This includes sexual abuse, emotional/psychological abuse, neglect, financial exploitation, and physical abuse [1,2]. Unfortunately, fewer than 1 in 24 cases of elder abuse are identified and reported to the authorities [1,2]. Emergency department (ED) assessment represents a critical but often missed opportunity to identify elder abuse, as medical evaluation for acute injury or illness is frequently the only nonfamily contact available to isolated older adults [4,5]. Though extreme cases of mistreatment may be apparent on a cursory assessment, most are subtle [6] and require all providers to be vigilant for clues.

As many geriatric injury victims receive radiographic imaging in the ED, diagnostic radiologists are optimally positioned to raise suspicion for mistreatment [7]. Imaging findings pathognomonic or highly indicative for child abuse are well defined in the literature and play a critical role in child abuse detection [8,9]. Identifying and reporting these findings is a core component of radiologist training and practice. On the contrary, little radiology literature currently exists describing imaging correlates of elder mistreatment [7]. Formal or informal training in elder abuse assessment does not exist for diagnostic radiologists. Research suggests, however, that radiologists are interested in education about elder abuse [10] and predict that imaging correlates may exist [7]. Our aim is to validate that prediction by beginning to characterise the imaging findings in elder abuse.

Case A

A 98-year-old woman with a past medical history of dementia presented to her primary care physician with a 1-week history of left upper extremity pain with bruising and inability to ambulate. A fracture was detected on radiographs, and she was sent to the ED for evaluation and treatment. Her home care included a 24/7 home health aide and her son, who visited biweekly and was designated as her health care proxy. In the ED, the mechanism of her arm injury was unknown. Her son and aide denied any history of recent falls or trauma. The aide proposed that the patient injured herself when banging her arm on her hospital bed at home, and the son endorsed this as a plausible mechanism.

A radiograph of the injured left upper extremity demonstrated an acute, displaced, transverse fracture through the proximal humeral metadiaphysis (Figure 1). This injury pattern is associated with a high-energy mechanism and appeared to be inconsistent with the reported injury etiology. A trauma consult was placed with concerns for elder abuse.

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the left humerus demonstrates an acute transverse fracture of the proximal humeral metadiaphysis. There is medial displacement of the distal fracture fragment, as well as apex lateral angulation and an overriding component of the fracture fragments.

Additional imaging included computed tomography (CT) of the left shoulder; radiographs of the left wrist and forearm, pelvis, left femur, and bilateral hips; and CT of the head. The left forearm and wrist radiographs demonstrated a chronic fracture deformity of the distal ulnar and distal radial diaphyses (Figure 2). The left hip and pelvis radiographs revealed an acute comminuted intertrochanteric fracture of the left proximal femur. An age-indeterminate fracture deformity of the right inferior pubic ramus was also noted. Though suspicion for elder abuse persisted among providers, it was not confirmed during the hospitalization. The patient was ultimately discharged home, though she was moved to a nursing home soon afterwards.

Figure 2.

Radiograph of the left forearm demonstrates bowed chronic fractures deformities of the distal ulnar and radial diaphyses. A well-corticated ossific density adjacent to the distal ulna likely represents sequelae from previous trauma. There is marked degenerative change and extensive remodelling of the radiocarpal articulation.

Case B

A 90-year-old woman with severe dementia presented to the ED for weakness and altered mental status reported by her son. He brought her in via cab, and she appeared disheveled, covered in feces, and fixed in the fetal position. Review of her medical records revealed a history of frequent falls, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and stroke with residual right-sided deficits. She had presented to our ED 1 year previously for pain following a mechanical fall. On physical examination, she had multiple ecchymoses over her body and face, including bilateral periorbital bruising. On initial presentation, she was hypothermic, hypernatremic, hypertensive, and bradycardic in triage. She was subsequently intubated for airway protection.

Several imaging studies were ordered in the ED, which revealed multiple fractures at various stages of healing. A chest radiograph demonstrated an acute, comminuted fracture of the right distal clavicle and multiple acute and chronic bilateral rib fractures (Figure 3). These fractures were further characterised with right clavicular radiographs and a CT of the chest. The chest CT revealed multiple acute right sided ribs fractures involving the right posterior first through third ribs, right anterior second and third ribs, right lateral eighth and ninth ribs, and right posterior 11th and 12th ribs. Non-acute healing fractures were seen involving the right anterolateral fourth through seventh ribs and right posterior fourth rib (Figure 4). There were additional healed chronic fracture deformities of the left anterior sixth and seventh ribs, left posterolateral third through sixth ribs, right anterolateral fourth and fifth ribs, and right posterolateral second, third, fifth, and 11th ribs. An acute, nondisplaced fracture of the right inferior pubic ramus and chronic fractures of the L2–L4 left transverse processes were noted on a CT of the abdomen and pelvis. A head CT revealed bilateral nasal bone fractures and a left frontal scalp hematoma without evidence of acute intracranial injury.

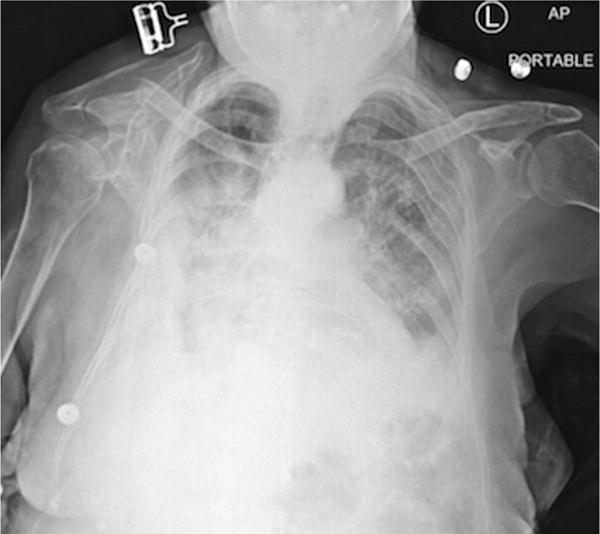

Figure 3.

A chest radiograph demonstrates an acute, comminuted, mildly displaced fracture of the distal third of the right clavicle. There are chronic fracture deformities of the left posterolateral third through sixth ribs and right posterolateral second, third, and fifth ribs. There are also findings of congestive heart failure with superimposed bilateral airspace opacities, right greater than left.

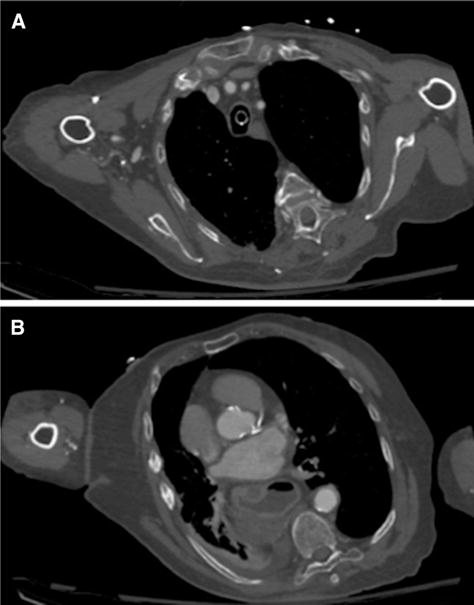

Figure 4.

(A) An axial image of a chest computed tomography at the level of the superior mediastinum demonstrates an acute, mildly displaced fracture of the anterior right second rib and a chronic fracture deformity of the lateral left third rib. (B) An axial image at the level of the heart demonstrates nonacute healing fractures of the lateral right sixth and seventh ribs. Additional acute, nonacute healing, and chronic rib fractures were present. An endotracheal tube, large hiatal hernia, coronary artery calcifications, and small right pleural effusion with adjacent consolidative change were noted.

During treatment, the patient was found to have abrasions to the labia and vaginal area suggestive of sexual abuse. Following admission, a brain magnetic resonance imaging was performed, which was notable for gyriform hemosiderin staining along the right Sylvian fissure, likely from prior subarachnoid hemorrhage. A geriatrics consult concluded that her physical exam findings were consistent with elder physical abuse and further investigation revealed previous adult protective services investigations for elder abuse. After a prolonged hospitalization, the patient was discharged to a shelter for elder abuse victims.

Discussion

These cases demonstrate the breadth of possible injuries in elder abuse and also suggest radiographic patterns that may be explored more deeply in future studies. These cases suggest that many of the same findings radiologists use to identify potential cases of child abuse are also present in elder abuse. In Case A, injuries inconsistent with the reported mechanism were present. Transverse humeral fractures most often require a high-energy mechanism of injury and the history provided by the patient’s caregivers of the patient banging her arm against a bedrail is unlikely to have caused this injury. This illustrates the importance of the radiologist reconciling injury patterns with mechanisms in the elderly as they do in the pediatric population. The detailed history necessary to perform such an analysis is often not provided as part of the imaging order; therefore, in cases with imaging findings consistent with high-energy mechanisms of injury but without documentation of such causes, the radiologist may want to discuss the reported history with the treating physician to ensure that potential cases of elder abuse are detected.

Both cases A and B had evidence of acute and chronic injuries in various stages of healing. Case B revealed acute fractures of the right clavicle and pelvis in combination with multiple acute, nonacute healing, and chronic, multifocal fractures of the bilateral ribs. In a pediatric case, these findings would have raised significant suspicion. Given the frequency of osteopenia/osteoporosis and fall injuries in the elderly, chronic bony injuries in older adults are often not considered to be of clinical consequence. Radiologists may mention these only in the body of their reports or even choose to not even report these findings as they have judged them to have little significance for the current clinical question. These cases illustrate that identifying, analysing, and reporting on these chronic injuries can likely contribute to increased recognition of elder abuse.

Uncommon fractures for accidental injury were present in these cases, suggesting that such injuries may be potential imaging findings for the detection of elder abuse. In case A, the patient had a chronic fracture deformity of the distal ulnar and distal radial diaphyses. While wrist injuries are common after a fall on outstretched hand, the distal radial metaphysis is much more commonly fractured. Fracture of the distal ulnar diaphysis is much less common, and the typical mechanism for this injury is trauma to a forearm raised in self-defense. In fact, a recent study on bruising patterns in elder abuse found that the bruising on the lateral wrist and forearm was more common in elder abuse victims than other older adults [6].

Radiographic findings potentially suggestive of elder abuse are summarized in Table 1. By describing these cases and highlighting their imaging characteristics, we hope to raise awareness among radiologists about this important and common phenomenon and to encourage future, larger-scale studies to identify imaging correlates. Next steps for researchers include comparing radiographic findings of abuse cases to those of unintentional injuries to identify patterns associated with or pathognomonic for elder abuse. Additionally, registries and other large databases may be used to assess the frequency and circumstances surrounding suspicious injury patterns such as ulnar diaphysis fracture or co-occurring acute and chronic fractures.

Table 1.

Radiographic findings potentially suggestive of elder abuse

| Injuries inconsistent with reported mechanism |

| Injuries in multiple stages of healing, particularly in maxillofacial region and upper extremities |

| Injury patterns uncommon in accidental injury, such as ulnar diaphysis fracture |

We have also identified changes to practice that may increase identification, including reconciliation of reported mechanism to injuries in geriatric trauma and increased focus on chronic bony findings. Most importantly, we hope that radiologists consider elder abuse as a possibility on their differential diagnosis, or this mistreatment may continue to be unrecognized.

Acknowledgments

Natalie Wong’s participation was supported by an MSTAR (Medical Student Training in Aging Research) grant from the American Federation for Aging Research. Tony Rosen’s participation has been supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant from the National Institute on Aging (R03 AG048109); he is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Mark Lachs is the recipient of a mentoring award in patient-oriented research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG022399).

References

- 1.National Center for Elder Abuse. The elder justice roadmap: a stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, financial, and social crisis. Available at: http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/Library/Gov_Report/docs/EJRP_Roadmap.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- 2.Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:292–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA. 1998;280:428–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond MC, Butler KH. Elder abuse and neglect: definitions, epidemiology, and approaches to emergency department screening. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:257–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyborne RD. Elder abuse: keeping the unthinkable in the differential. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:566–7. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiglesworth A, Austin R, Corona M, et al. Bruising as a marker of physical elder abuse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy K, Waa S, Jaffer H, Sauter A, Chan A. A literature review of findings in physical elder abuse. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013;64:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, Silver HK. The battered-child syndrome. Jama. 1962;181:17–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinman PK. Diagnostic imaging in infant abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:703–12. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.4.2119097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harpe JM, Rosen T, LoFaso VM, et al. Diagnostic radiologists’ knowledge, attitudes, training, and practice in elder abuse detection. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:S248. [Google Scholar]