Abstract

Background

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common tremor disorder. In addition to its hallmark feature, kinetic tremor of the upper limbs, patients may have a number of non-motor symptoms and signs (NMS). Several lines of evidence suggest that ET is a neurodegenerative disorder and certain NMS may antedate the onset of tremor. This article comprehensively reviews the evidence for the existence of a “premotor phase” of ET, and discusses plausible biological explanations and implications.

Methods

A PubMed search in May 2017 identified articles for this review.

Results

The existence of a premotor phase of ET gains support primarily from longitudinal data. In individuals who develop incident ET, baseline (i.e., premotor) evaluations reveal greater cognitive dysfunction, a faster rate of cognitive decline, and the presence of a protective effect of education against dementia. In addition, baseline evaluations also reveal more self-reported depression, antidepressant medication use, and shorter sleep duration in individuals who eventually develop incident ET. In cross-sectional studies, certain personality traits and NMS (e.g., olfactory dysfunction) also suggest the existence of a premotor phase.

Discussion

There is preliminary evidence supporting the existence of a premotor phase of ET. The mechanisms are unclear; however, the presence of Lewy bodies in some ET brains in autopsy studies and involvement of multiple neural networks in ET as evident from the neuroimaging studies, are possible contributors. Most evidence is from a longitudinal cohort (Neurological Disorders of Central Spain: NEDICES); additional longitudinal studies are warranted to gain better insights into the premotor phase of ET.

Keywords: Essential tremor, premotor, prodromal, pre-clinical, non-motor

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common tremor disorder among adults.1 Although ET has long been regarded as a monosymptomatic benign movement disorder primarily characterized by kinetic tremor of the upper limbs, a range of additional motor and non-motor features has been described. Among the non-motor symptoms and signs (NMS) that have been described are cognitive impairment, depression, apathy, anxiety, personality characteristics, olfactory deficits, hearing problems, and sleep disturbances.2,3 There is evidence to suggest that most of the NMS observed in ET are not just epiphenomena, rather they are parts of the primary disease process.4 In this backdrop, the question that is thought provoking and the answer to which remains largely elusive is what does appear first in ET: tremor or the NMS? Other movement disorders in which NMS are frequently present and substantially worsen the health-related quality of life are Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD). In PD, certain NMS such as rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD), depression, and olfactory dysfunction may antedate the onset of motor symptoms by decades.5,6 Similarly patients with HD may have behavioral and/or cognitive problems long before the onset of motor symptoms.7,8 Considering the availability of robust evidence regarding the occurrence of these NMS before the onset of motor symptoms, the concept of a premotor stage is now well established in PD and HD. However, even though patients with ET can be burdened with several NMS, there has been no discussion as to whether there is a premotor phase in ET. It is important to review the evidence for the existence of a premotor phase in ET. Such a study could provide further insights into the neurobiological underpinnings of ET and establish the foundation for pre-clinical trials.

Evidence indicating that some of the NMS may appear before the onset of tremor in patients with ET would favor the existence of a premotor phase in ET. In this article, we comprehensively review the evidence for the presence of a premotor phase in ET, and discuss plausible biological explanations and implications.

Methodology

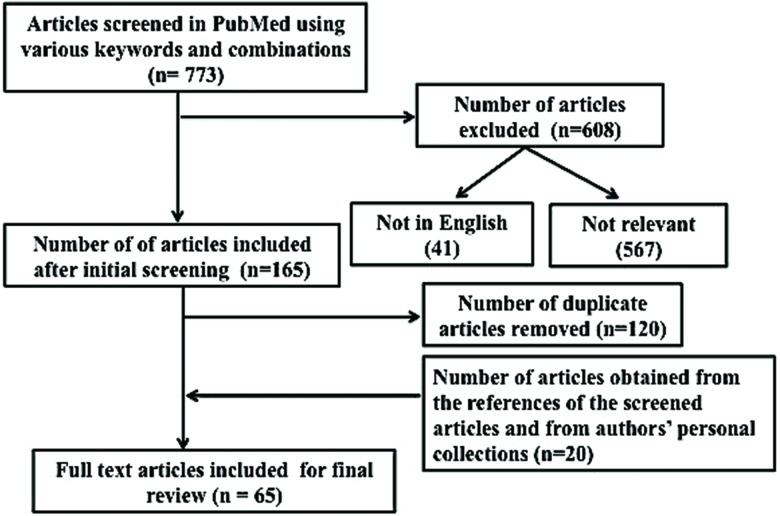

In May 2017, the authors used PubMed to search for the relevant literature using the term “essential tremor” with additional search terms being “premotor”, “prodromal”, “non-motor”, “cognition”, “memory”, “depression”, “apathy”, “anxiety”, “sleep”, “olfaction”, “hearing”, and “personality”. This search yielded 773 articles (Table 1, Figure 1). During the initial screening of the abstracts/full texts, the articles that were not relevant to this review, the duplicates, and those that were published in languages other than English were removed, leaving 45 remaining articles. The references from these articles as well as full text articles/abstracts from authors’ personal collections were also thoroughly searched for any additional articles, yielding 20 (from references: 19, from personal collections: 1) more articles (Table 1, Figure 1). In total, 65 articles pertinent to this topic were included for this review (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1. Results of Search for Articles from PubMed Using Various Key Words and their Combinations.

| Key Words and Combinations | Number of Publications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Included | Excluded | |

| Essential tremor AND premotor | 29 | 4 | 25 (not in English: 0, not relevant: 25) |

| Essential tremor AND prodromal | 5 | 0 | 5 (not in English: 0, not relevant: 5) |

| Essential tremor AND non-motor | 71 | 24 | 47 (not in English: 4, not relevant: 43) |

| Essential tremor AND cognition | 138 | 29 | 109 (not in English: 6, not relevant: 103) |

| Essential tremor AND memory | 71 | 17 | 54 (not in English: 2, not relevant: 52) |

| Essential tremor AND depression | 170 | 26 | 144 (not in English: 12, not relevant: 132) |

| Essential tremor AND apathy | 7 | 5 | 2 (not in English: 0, not relevant: 2) |

| Essential tremor AND anxiety | 101 | 14 | 87 (not in English: 9, not relevant: 78) |

| Essential tremor AND sleep | 74 | 16 | 58 (not in English: 5, not relevant: 53) |

| Essential tremor AND olfaction | 32 | 8 | 24 (not in English: 0, not relevant: 24) |

| Essential tremor AND hearing | 31 | 12 | 19 (not in English: 0, not relevant: 19) |

| Essential tremor AND personality | 44 | 10 | 34 (not in English: 3, not relevant: 31) |

| Total number of articles included for review after removing the duplicates | 45 | ||

| Total number of articles included from the reference sections of the shortlisted articles | 19 | ||

| Total number of articles included from authors’ personal collections | 1 | ||

| Final number of articles include for review | 65 | ||

Figure 1. Flow diagram summarizing the steps of our literature search.

Evidence suggesting presence of a premotor phase of ET

Cognitive dysfunction and the incidence of ET

Cognitive dysfunction in patients with ET has been reported in several case–control studies and deficits have been documented in several cognitive domains including attention, memory, visuospatial functions, and executive functions.9,10 With the exception of one longitudinal study (Neurological Disorders in Central Spain: NEDICES cohort), all others have compared cognitive function of prevalent ET cases with healthy controls (i.e., case-control studies).11 Owing to their cross-sectional design, these studies were therefore not able to evaluate whether cognitive impairment occurred prior to the onset of tremor in ET. In NEDICES, a longitudinal cognitive evaluation was performed in three groups of elderly subjects aged 65 years and older (premotor ET, prevalent ET, and controls).11 The premotor ET group comprised patients who were apparently normal at baseline and developed ET during the follow up (mean baseline age: 73.0±5.7 years) (i.e., they had incident ET at follow up) whereas the prevalent ET group comprised patients who already had a diagnosis of ET at baseline (mean baseline age: 73.6±6.3 years). The controls did not have a diagnosis of ET either at baseline or during follow up (mean baseline age: 72.4±5.8 years). Interestingly, the premotor ET group performed more poorly than controls on the baseline 37-item Mini Mental Status Examination (37-MMSE).11 Furthermore, the change in the 37-MMSE from baseline to first follow up (i.e., the rate of cognitive decline over a mean of 3.4±0.5 years) was greater in the premotor ET group than the controls. Although 37-MMSE is a screening instrument that provides insight into global cognitive function and is not a detailed cognitive test, these data suggest that subtle cognitive dysfunction in ET may precede the motor signs, and that cognitive function seems to be declining at a more rapid rate than in age-matched controls.

In another set of longitudinal analyses from the same data set, the NEDICES investigators explored the effects of baseline education on risk of incident dementia in premotor ET and prevalent ET groups.12 There was a differential effect of education on the risk of incident dementia in premotor and prevalent ET; thus, 16.7% of premotor ET patients with lower education (i.e., less than or equal to primary education) developed incident dementia vs. 3.3% of premotor ET patients with higher education (i.e., greater or equal to secondary education). Interestingly, this difference in risk of incident dementia was not observed in prevalent ET patients with lower vs. higher education. The data suggested the presence of a protective effect of education against dementia in premotor ET but not in prevalent ET patients. The authors interpreted their results as follows: as the pathological changes related to dementia in ET are presumed to be gradual and slowly progressive in nature, it is possible that these changes occurred before the onset of tremor in the incident ET cases and the protective effect of education was probably effective only up to a certain threshold of neurodegeneration.

Depression and incidence ET

Depression has commonly been reported in patients with ET13,14 and in ET has also been noted to be associated with embarrassment and poor health-related quality of life.15,16 As discussed above, patients with other movement disorders, including PD and HD, note the presence of depression prior to the onset of motor symptoms. However, similar reports in patients with ET are scant in the current literature. Louis et al.17 prospectively studied the relationship between self-reported depression at baseline and the risk of incident ET in the NEDICES cohort. In this longitudinal study, baseline self-reported depression and baseline self-reported use of antidepressants were each associated with incident ET (respective relative risks = 1.78 and 1.90). These data suggest that depression may be part of the primary disease process in ET rather than a response to the presence and disabling effects of tremor. This idea gains additional support from studies that did not detect a correlation between the severity of depression and the severity of tremor in patients with ET.18,19 Aside from this study of the NEDICES cohort, one retrospective study documented the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms prior to the index date (date on which a diagnosis of ET was made).20 In this 45-year retrospective study (1935–1979) in Rochester, Minnesota, the authors documented the presence of psychoneurosis in 16% of ET cases prior to the index date. However, details regarding the nature and onset of “psychoneurosis” were not explicitly described nor were control data reported in order to interpret whether the prevalence in ET cases was elevated above and beyond normal levels.

Sleep dysregulation as a premotor symptom

Although sleep disturbances like RBD has been established as a premotor symptom in PD and other synucleinopathies such as multiple system atrophy and dementia with Lewy bodies (LB), there is little information about premotor sleep dysregulation in ET. Cross-sectional studies have furnished mixed evidence regarding sleep disturbances in ET14,21,22 although the majority suggest that there is a problem,2 and several studies22,23 have reported that sleep quality scores in ET fall intermediately between patients with PD and healthy controls. However, it is difficult to ascertain if the sleep disturbances occur before or after the onset of tremor. Normal sleep is regulated through a coordinated expression of several neurotransmitters in the brainstem and hypothalamic neurons. In this context, it is important to note that the neuropathological investigations have revealed the presence of LB in brainstem structures especially in the locus coeruleus in the brains of some ET patients.24,25 As the premotor symptoms in PD (RBD, olfactory dysfunction, constipation, depression) have been speculated to be the result of caudo-cranial progression of LB deposition, which usually begins in the olfactory bulb and subsequently involves the brainstem structures,26 it is possible that as in PD the LB deposition in some of the ET patients begins before the onset of tremor and perhaps contributes towards a few of the NMS such as sleep dysregulation. Currently we are aware of only one study that prospectively studied the relationship between sleep duration and ET.27 In this study by Benito-León et al.,27 3,303 participants were followed up for a median duration of 3.3 years during which 76 subjects developed incident ET. Interestingly, participants who reported short duration of sleep (≤5 hours/day) at baseline had a higher risk of developing incident ET. The results of this study raise two possibilities - either short sleep duration is a premotor symptom of ET or short sleep duration is a risk factor for ET. Considering the fact that there are no biologically plausible explanations for a cause-and-effect relationship of short sleep duration and risk of ET, the short sleep duration is more likely to represent a premotor symptom of ET. Nonetheless, more studies are warranted in order to develop a more conclusive picture of the role of sleep dysregulation in the natural course of ET. Reports of RBD, which is an established premotor feature of PD, are rare in patients with ET. In a recently published abstract, Barbosa et al.28 reported the presence of RBD in 26.4% patients with ET and those ET patients with RBD had more autonomic dysfunction compared to those without RBD. As such a high prevalence of RBD has never been reported in patients with ET before, further studies need to confirm this finding and place it within the context of control data.

Restless legs syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a comorbidity in several neurological disorders including PD, ET, and Tourette syndrome.29–31 In fact, many patients with PD have RLS before the onset of motor symptoms. In a large prospective study of US veterans with a median follow-up time of 7.8 years, individuals with prevalent RLS had a twofold higher risk of incident PD than did individuals without RLS.32 Another prospective population-based study of US health professionals has also revealed higher rates of incident PD in subjects having severe prevalent RLS.33 These large population based prospective studies suggest that RLS is a premotor symptom of PD. There are fewer epidemiological studies on RLS in ET. In a study by Wu et al., which estimated the prevalence of ET and its NMS in a rural population in Shanghai, China, the prevalence of RLS was significantly higher in ET cases compared to healthy controls.34 However, as it was a cross sectional study, the natural course of RLS in ET was not clear. Ondo and Lai30 reported the presence of RLS in 33% of their ET patients who were consecutively evaluated; however, no control group was enrolled for comparison. Conversely none of the 68 consecutive patients with RLS who were recruited during the same time in this study had overtly pathological tremor amounting to a diagnosis of ET.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one case report that described the onset of RLS (childhood) much earlier than the onset of tremor (teen age) in a patient with ET.35 Prospective studies are warranted to gain better insights into the complex relationship between ET and RLS.

Premorbid personality in ET

Personality traits are defined as the relatively enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish individuals from one another.36 As personality traits may remain stable for a fair amount of time in a person’s life, traits (if premorbid) specific to a disease can be speculated to be a component of the premotor spectrum. Several studies have assessed personality traits in patients with movement disorders such as PD, HD, and ET. We are aware of three cross-sectional studies on patients with ET in which personality traits were compared with healthy controls.37–39 In the studies by Chaterjee et al.37 and Thenganatt et al.,38 the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ) was used to assess the personality traits and in both these studies patients with ET scored higher in the harm avoidance (HA) subscales. A high score on the HA subscale indicates that the person is pessimistic, fearful, shy, anxious, and is easily fatigued. Lorenz et al.39 used a revised version of the Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-R) to assess the personality traits in German patients with ET. The EPQ-R measures three dimensions of personality: extraversion (E), neuroticism (N), and psychoticism (P).40 In this study, the authors reported a significantly lower score on the P-scale, suggesting that ET patients are kinder, more tender-minded, and less aggressive than the normal population. Considering the cross-sectional design of the study, it is difficult to ascertain whether the personality trait observed by Lorenz et al. was premorbid personality or it was the psychological response to the tremor of ET. However, there is evidence that suggests that the traits represented on the Eysenck’s P-scale are heritable41,42 and they may have direct43,44 or indirect association45 with androgen action. This information suggests that low P-score is a premorbid personality in ET, rather than an epiphenomenon. As the complex interplay between testosterone and serotonin may affect aggression, fear and anxiety in a person,45,46 the results of the studies by Chatterjee et al.37 and Thenganatt et al.38 also appear to favor a premorbid personality in ET rather than secondary response to tremor, the reason being the personality dimensions of the TPQ have been associated with changes in neurotransmitter activity as the patients with high HA scores have increased 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) release from presynaptic neurons after the administration of serotonergic agonists.47

Clues from olfactory dysfunction

Olfactory dysfunction (hyposmia/anosmia) is an established premotor symptom of PD.6,48 However, the literature on olfactory dysfunction in ET remains controversial as studies have either reported no olfactory dysfunction49–52 or greater dysfunction53–55 in patients with ET compared to controls. In one of the studies reporting olfactory dysfunction in ET, the degree of deficit was unrelated to the severity of tremor and duration.53 Similar results (no correlation with disease stage and severity) have been described in the context of olfactory deficits in PD.56 This implies olfactory deficits, when present, are perhaps parts of the primary disease process rather being a secondary response.

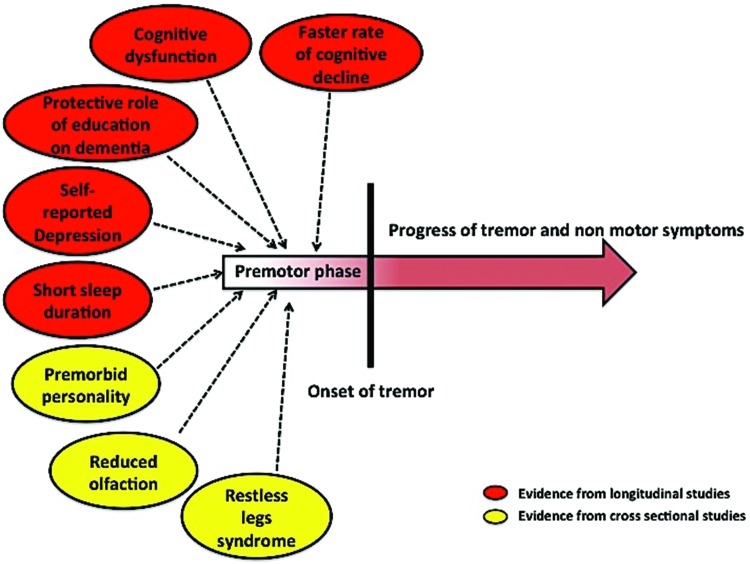

Hypotheses for the premotor phase

To date, the bulk of evidence that favors the existence of a premotor phase of ET is derived from the studies on the NEDICES cohort. In individuals who develop incident ET, baseline (i.e., premotor) evaluations reveal greater cognitive dysfunction, a faster rate of cognitive decline, and the presence of a protective effect of education against dementia. In addition, in these same individuals, baseline (i.e., premotor) evaluations reveal more self-reported depression and antidepressant medication use, and shorter sleep duration. These data are the suggestive evidence of the existence of a premotor phase of ET (Figure 2). In addition, certain personality traits and NMS such as RLS and possible olfactory dysfunction, which have long been regarded as premotor symptoms of PD, also provide some evidence that a premotor phase exists in ET (Figure 2). From the point of view of the disease pathophysiology, there is biological support for this notion. As described above, the neuropathological investigations have revealed LB deposition in several regions of the brain of ET patients in some studies. It is very much possible that similar to PD, the natural course of certain NMS may follow the degree and distribution of the LB in the brain. Numerous structural and functional neuroimaging studies have explored the neural correlates of ET.57,58 Although alteration in the components of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network has been the major result across the imaging studies,59–62 several studies have also noted abnormalities in structures that do not have any apparent role in genesis of tremor. For example, the functional neuroimaging studies by Benito-León et al.61 and Fang et al.63 have revealed altered connectivity in multiple resting state brain networks (default mode network, fronto-parietal network, visual network), which are presumed to regulate various cognitive processes. Similarly the structural neuroimaging studies by Bhalsing et al., which were aimed at comparing the gray64 and white matter65 microstructural changes in ET patients with and without cognitive impairment, have revealed structural alterations in several regions of brain (reduced gray matter volume in the medial frontal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, insula, cingulate, and white matter changes in frontal cortex, cingulate, superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus) that have not been described to play any role in the genesis of tremor in ET. These data suggest that the disease pathology in ET is not limited only to the motor network, but, rather, it is possible that multiple structures or networks may be involved in parallel. In other words, ET may be a neurodegenerative disorder with alteration of several neural networks. It is possible that the beginning of alterations in certain networks predates the alterations of other networks. Hence if the alteration in networks or structures that theoretically correspond to a NMS occur earlier than alterations in the motor network, the patient will have the respective NMS as a premotor symptom.

Figure 2. Summary of the evidence that favors the existence of a premotor phase of essential tremor.

Conclusion

To summarize, although limited in number, there is some current evidence that suggests the existence of a premotor phase of ET. As a majority of the evidence is from studies involving the NEDICES cohort, more population-based longitudinal studies are crucial for further characterization of the premotor phase of ET. In this context, individuals who are at higher risk of developing ET (i.e., unaffected first-degree relatives of ET patients) appear to be an ideal population for the future longitudinal studies in order to gain more insights into the premotor phase of ET (Table 2); no data on the prevalence of non-motor symptoms in these at-risk relatives have been published.

Table 2. Future Directions for Research on the Premotor Phase of Essential Tremor.

| More population-based longitudinal studies. |

| Confirmation of the results of the studies on the NEDICES cohort in other populations. |

| Longitudinal clinical evaluation of individuals at high risk of developing ET (e.g., unaffected first-degree relatives of ET cases). |

| Functional and structural neuroimaging in high-risk individuals and their correlation with premotor symptoms, if present. |

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Lenka is sponsored by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR, New Delhi) for his MD-PhD (Clinical Neurosciences) fellowship at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India. Dr. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the Commission of the European Union (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD—platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451). Dr. Louis has received research support from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R01 NS094607 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS39422 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS046436 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS073872 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS085136 (principal investigator) and NINDS #R01 NS088257 (principal investigator). He has also received support from the Claire O’Neil Essential Tremor Research Fund (Yale University).

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement: Not applicable for this category of article.

References

- 1.Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2010;25:534–541. doi: 10.1002/mds.22838. doi: 10.1002/mds.22838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis ED. Non-motor symptoms in essential tremor: A review of the current data and state of the field. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;22((Suppl. 1)):S115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.08.034. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandran V, Pal PK. Essential tremor: beyond the motor features. Park Relat Disord. 2012;18:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.12.003. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jhunjhunwala K, Pal PK. The non-motor features of essential tremor: a primary disease feature or just a secondary phenomenon? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2014:4. doi: 10.7916/D8D798MZ. doi: 10.7916/D8D798MZ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri KR, Schapira AH V. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:464–474. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70068-7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman JG, Postuma R. Premotor and nonmotor features of Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27:434–441. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000112. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snowden JS, Craufurd D, Thompson J, Neary D. Psychomotor, executive, and memory function in preclinical Huntington’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24:133–145. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.2.133.998. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.2.133.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenka A, Kamble NL, Sowmya V, Jhunjhunwala K, Yadav R, Netravathi M, et al. Determinants of onset of Huntington’s disease with behavioral symptoms: Insight from 92 patients. J Huntingtons Dis. 2015;4:319–324. doi: 10.3233/JHD-150166. doi: 10.3233/JHD-150166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F. Population-based case-control study of cognitive function in essential tremor. Neurology. 2006;66:69–74. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192393.05850.ec. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192393.05850.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bermejo-Pareja F. Essential tremor--a neurodegenerative disorder associated with cognitive defects? Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:273–282. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.44. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Sánchez-Ferro Á, Bermejo-Pareja F. Rate of cognitive decline during the premotor phase of essential tremor: a prospective study. Neurology. 2013;81:60–66. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297ef2b. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297ef2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benito-León J, Contador I, Louis ED, Cosentino S, Bermejo-Pareja F. Education and risk of incident dementia during the premotor and motor phases of essential tremor (NEDICES) Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogu O, Louis ED, Sevim S, Kaleagasi H, Aral M. Clinical characteristics of essential tremor in Mersin, Turkey: a population-based door-to-door study. J Neurol. 2005;252:570–574. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0700-8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandran V, Pal PK, Reddy JYC, Thennarasu K, Yadav R, Shivashankar N. Non-motor features in essential tremor. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;125:332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01573.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis ED, Huey ED, Gerbin M, Viner AS. Depressive traits in essential tremor: Impact on disability, quality of life, and medication adherence. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1349–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03774.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis ED, Cosentino S, Huey ED. Depressive symptoms can amplify embarrassment in essential tremor. J Clin Mov Disord. 2016;3:11. doi: 10.1186/s40734-016-0039-6. doi: 10.1186/s40734-016-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis ED, Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group Self-reported depression and anti-depressant medication use in essential tremor: cross-sectional and prospective analyses in a population-based study. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:1138–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01923.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacritz LH, Dewey R, Giller C, Cullum CM. Cognitive functioning in individuals with “benign” essential tremor. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:125–129. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702001121. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tröster AI, Woods SP, Fields JA, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Higginson CI, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in essential tremor: an expression of cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathophysiology? Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:143–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00341.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajput A, Offord KP, Beard CM, Kurland L. Essential tremor in Rochester, Minnesota: a 45-year study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:466–470. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.5.466. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adler CH, Hentz JG, Shill HA, Sabbagh MN, Driver-Dunckley E, Evidente VGH, et al. Probable RBD is increased in Parkinson’s disease but not in essential tremor or restless legs syndrome. Park Relat Disord. 2011;17:456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.007. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerbin M, Viner AS, Louis ED. Sleep in essential tremor: a comparison with normal controls and Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barut BO, Tascilar N, Varo A. Sleep disturbances in essential tremor and Parkinson disease: a polysomnographic study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:655–662. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4778. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JPG, Honig LS, Rajput A, Robinson CA, et al. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130:3297–3307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis ED, Honig LS, Vonsattel JP, Maraganore DM, Borden S, Moskowitz CB. Essential tremor associated with focal nonnigral Lewy bodies: a clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1004–1007. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.1004. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, De Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F. Short sleep duration heralds essential tremor: A prospective, population-based study. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1700–1707. doi: 10.1002/mds.25590. doi: 10.1002/mds.25590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbosa R, Mendonça M, Ladeira FR, Migue RB. Relation between REM-sleep behaviour disorder and dysautonomic symptoms in essential tremor patients. Mov Disord. 2017;32:500. doi: 10.7916/D8Z61VW5. doi: 10.1002/mds.27087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lespérance P, Djerroud N, Diaz Anzaldua A, Rouleau GA, Chouinard S, Richer F. Restless legs in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1084–1087. doi: 10.1002/mds.20100. doi: 10.1002/mds.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ondo WG, Lai D. Association between restless legs syndrome and essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21:515–518. doi: 10.1002/mds.20746. doi: 10.1002/mds.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peeraully T, Tan E-K. Linking restless legs syndrome with Parkinson’s disease: clinical, imaging and genetic evidence. Transl Neurodegener. 2012;1:6. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-6. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szatmari S, Bereczki D, Fornadi K, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Molnar MZ. Association of restless legs syndrome with incident Parkinson’s disease. Sleep. 2017;40:S5–S9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw065. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong JC, Li Y, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A, Gao X. Restless legs syndrome: an early clinical feature of Parkinson disease in men. Sleep. 2014;37:369–372. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3416. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y, Wang X, Wang C, Suna Q, Song N, Zhou Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of non-motor symptoms of essential tremor in Shanghai rural area. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;22:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.10.617. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.10.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larner AJ, Allen CM. Hereditary essential tremor and restless legs syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:254. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.858.254. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.858.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts BW, Mroczek D. Personality trait change in adulthood. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee A, Jurewicz EC, Applegate LM, Louis ED. Personality in essential tremor: further evidence of non-motor manifestations of the disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:958–961. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.037176. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.037176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thenganatt MA, Louis ED. Personality profile in essential tremor: a case-control study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:1042–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.05.015. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenz D, Schwieger D, Moises H, Deuschl G. Quality of life and personality in essential tremor patients. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1114–1118. doi: 10.1002/mds.20884. doi: 10.1002/mds.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Hodder & Stoughton; Kent, UK: 1975. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. doi: 10.1177/014662168000400106. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neale MC, Philippe Rushton J, Fulker DW. Heritability of item responses on the Eysenck personality questionnaire. Pers Individ Dif. 1986;7:771–779. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(86)90075-9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillespie NA, Evans DE, Wright MM, Martin NG. Genetic simplex modeling of Eysenck’s dimensions of personality in a sample of young Australian twins. Twin Res. 2004;7:637–648. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663814. doi: 10.1375/twin.7.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eysenck HJ. Biological dimensions of personality. Handbook of personality: theory and research. 1990:244–276. In. Available at. http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1990-98135-010.

- 44.Turakulov R, Jorm AF, Jacomb PA, Tan X, Easteal S. Association of dopamine-β-hydroxylase and androgen receptor gene polymorphisms with Eysenck’s P and other personality traits. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;37:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2003.08.011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Birger M, Swartz M, Cohen D, Alesh Y, Grishpan C, Kotelr M. Aggression: the testosterone-serotonin link. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montoya ER, Terburg D, Bos PA, van Honk J. Testosterone, cortisol, and serotonin as key regulators of social aggression: a review and theoretical perspective. Motiv Emot. 2012;36:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9264-3. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerra G, Zaimovic A, Timpano M, Zambelli U, Delsignore R, Brambilla F. Neuroendocrine correlates of temperamental traits in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:479–496. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00004-4. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:329–339. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Busenbark KL, Huber SJ, Greer G, Pahwa R, Koller WC. Olfactory function in essential tremor. Neurology. 1992;42:1631–162. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.8.1631. doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.8.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah M, Muhammed N, Findley LJ, Hawkes CH. Olfactory tests in the diagnosis of essential tremor. Park Relat Disord. 2008;14:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.12.006. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quagliato LB, Viana MA, Quagliato EMAB, Simis S. Olfaction and essential tremor. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67:21–24. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000100006. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2009000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKinnon J, Evidente V, Driver-Dunckley E, Premkumar A, Hentz J, Shill H, et al. Olfaction in the elderly: a cross-sectional analysis comparing Parkinson’s disease with controls and other disorders. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120:36–39. doi: 10.3109/00207450903428954. doi: 10.3109/00207450903428954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louis ED, Bromley SM, Jurewicz EC, Watner D. Olfactory dysfunction in essential tremor: a deficit unrelated to disease duration or severity. Neurology. 2002;59:1631–1633. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000033798.85208.f2. doi: 10.1212/WNL.61.6.871-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Applegate LM, Louis ED. Essential tremor: mild olfactory dysfunction in a cerebellar disorder. Park Relat Disord. 2005;11:399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.03.003. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Louis ED, Rios E, Pellegrino KM, Jiang W, Factor-Litvak P, Zheng W. Higher blood harmane (1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole) concentrations correlate with lower olfactory scores in essential tremor. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.02.013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doty RL, Deems DA, Stellar S. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a general deficit unrelated to neurologic signs, disease stage, or disease duration. Neurology. 1988;38:1237–1244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1237. doi: 10.1212/WNL.38.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Louis ED, Huang CC, Dyke JP, Long Z, Dydak U. Neuroimaging studies of essential tremor: how well do these studies support/refute the neurodegenerative hypothesis? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2014:4. doi: 10.7916/D8DF6PB8. doi: 10.7916/D8DF6PB8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharifi S, Nederveen AJ, Booij J, Van Rootselaar AF. Neuroimaging essentials in essential tremor: a systematic review. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;5:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.003. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lenka A, Bhalsing KS, Panda R, Jhunjhunwala K, Naduthota RM, Saini J, et al. Role of altered cerebello-thalamo-cortical network in the neurobiology of essential tremor. Neuroradiology. 2017;59:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1771-1. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1771-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yin W, Lin W, Li W, Qian S, Mou X. Resting state fMRI demonstrates a disturbance of the cerebello-cortical circuit in essential tremor. Brain Topogr. 2016;29:412–418. doi: 10.1007/s10548-016-0474-6. doi: 10.1007/s10548-016-0474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Romero JP, Hernández-Tamames JA, Manzanedo E, Álvarez-Linera J, et al. Altered functional connectivity in essential tremor: a resting-state fMRI study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1936. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001936. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buijink AWG, Van Der Stouwe AMM, Broersma M, Sharifi S, Groot PFC, Speelman JD, et al. Motor network disruption in essential tremor: a functional and effective connectivity study. Brain. 2015;138((10)):2934–2947. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv225. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fang W, Chen H, Wang H, Zhang H, Liu M, Puneet M, et al. Multiple resting-state networks are associated with tremors and cognitive features in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1926–36. doi: 10.1002/mds.26375. doi: 10.1002/mds.26375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhalsing KS, Upadhyay N, Kumar KJ, Saini J, Yadav R, Gupta AK, et al. Association between cortical volume loss and cognitive impairments in essential tremor. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:874–883. doi: 10.1111/ene.12399. doi: 10.1111/ene.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhalsing KS, Kumar KJ, Saini J, Yadav R, Gupta AK, Pal PK. White matter correlates of cognitive impairment in essential tremor. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:448–453. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4138. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]