Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The Memory in Diabetes (MIND) substudy of the ACCORD study, a double 2×2 factorial parallel-group randomised clinical trial, tested whether intensive compared with standard management of hyperglycaemia, BP or lipid levels reduced cognitive decline and brain atrophy in 2977 people with type 2 diabetes. We describe the results of the observational extension study, ACCORDION MIND (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT00182910), which aimed to measure the long-term effects of the three ACCORD interventions on cognitive and brain structure outcomes approximately 4 years after the trial ended.

Methods

Participants (mean diabetes duration 10 years; mean age 62 years at baseline) received a fourth cognitive assessment and a third brain MRI, targeted at 80 months post-randomisation. Primary outcomes were performance on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) and total brain volume (TBV). The contrast of primary interest compared glycaemic intervention groups at the ACCORDION visit; secondary contrasts were the BP and lipid interventions.

Results

Of the surviving ACCORD participants eligible for ACCORDION MIND, 1328 (68%) were re-examined at the ACCORDION follow-up visit, approximately 47 months after the intensive glycaemia intervention was stopped. The significant differences in therapeutic targets for each of the three interventions (glycaemic, BP and lipid) were not sustained. We found no significant difference in 80 month mean change from baseline in DSST scores or in TBV between the glycaemic intervention groups, or the BP and lipid interventions. Sensitivity analyses of the sites with ≥70% participation at 80 months revealed consistent results.

Conclusions/interpretation

The ACCORD interventions did not result in long-term beneficial or adverse effects on cognitive or brain MRI outcomes at approximately 80 months follow-up. Loss of separation in therapeutic targets between treatment arms and loss to follow-up may have contributed to the lack of detectable long-term effects.

Keywords: Abnormal white matter volume, Brain MRI, Cognitive impairment, Total brain volume, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cognitive impairment and structural brain abnormalities [1–3]. Hypertension and dyslipidaemia are common comorbidities in type 2 diabetes. Evidence suggests that individuals with diabetes and elevated BP are more likely to have prevalent cognitive impairment and more brain atrophy than those with diabetes alone [4–7].

This report describes the results of ACCORDION MIND, the observational extension of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Memory in Diabetes (ACCORD MIND) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00182910 (see the ACCORDION Follow-on Study Group members listed in the electronic supplementary material [ESM]). ACCORD was a double 2×2 factorial clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00000620) initiated to test whether intensive compared with standard management of hyperglycaemia, BP or lipid levels reduced cardiovascular events or mortality, and secondarily total mortality [8]. The Memory in Diabetes (MIND) trial was embedded in the larger trial to test whether these same interventions also reduced decline in brain function and structure over a 40 month period [9]. ACCORD targeted people with long-standing diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular events with HbA1c levels of ≥7.5% (≥58 mmol/mol).

In ACCORD MIND, cognitive tests were administered at baseline (n=2977), 20 months and 40 months post-randomisation. The primary cognitive outcome in MIND was 40 month performance on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) [10]. The DSST was chosen because it is a test of psychomotor function and speed, domains believed to be reflective of vascular cognitive impairment, but it also includes aspects of learning and working memory [10], domains also affected by diabetes. The DSST has a wide distribution of scores in the target population, avoiding ceiling or floor effects.

Brain MRI was acquired in a subset of the MIND sample at baseline (n=614) and 40 months. The primary brain MRI outcome was total brain volume (TBV), which was chosen based on evidence that diabetes can lead to mixed vascular and neurodegenerative changes [11,12] and changes in TBV over time [13], and can affect the relationship between TBV and cognitive function. The secondary brain MRI outcome was abnormal white matter volume (AWM), which is indicative of diffuse and focal ischaemic, demyelinating and inflammatory processes that can lead to small vessel disease, and is associated with diabetes and impaired cognition [14,15].

The results of ACCORD MIND were as follows. We found no differences in mean DSST scores between the standard and intensive glycaemic groups at 40 months [14,15]. There was a modest but significant beneficial effect on TBV at 40 months, whereby the intensive group had a higher TBV (mean 4.6 cm3) than the standard group. We also found no significant differences in cognition between the treatment arms of the BP or lipid interventions [16]. Intensive BP control was associated with significantly lower TBV at 40 months follow-up. Interestingly, participants receiving the combination of intensive glycaemic and standard antihypertensive therapy experienced ~62% less TBV loss compared with the loss in the other three treatment arms (~−11.0 cm3 vs −17.8 cm3; p<0.0007) at 40 months follow-up. At 40 months, there was also significantly more AWM in the intensive glycaemictreatment group (mean 1.89 cm3 [95% CI 1.78, 2.0]) compared with the standard treatment group (1.71 cm3 [1.62, 1.80]; ratio of means 1.10 cm3 [1.02, 1.19]; p=0.0156). However, this effect seemed to be restricted to participants <60 years (interaction between the glycaemia intervention and baseline age; p=005) [16].

Previous extension studies of clinical trials in persons with diabetes have reported a sustained effect of an intervention beyond the period of exposure [17,18]. With ACCORDION MIND we sought to determine whether there were sustained or delayed long-term effects of the ACCORD MIND intensive interventions on the primary outcomes of the DSST and TBV, and the secondary cognitive endpoints and AWV MRI endpoint at ~80 months follow-up (or 40 months after the ACCORD MIND study end). Specifically, we sought to determine whether: (1) the mean change from baseline in cognitive function as measured by the DSST was less; and (2) the mean change from baseline in TBV was lower in the group randomised to intensive glycaemic control compared with the group randomised to standard glycaemic control. We also pursued similar analyses comparing changes in DSST and TBV, and secondary outcomes between the BP and lipid intensive and standard intervention arms, and measured possible interactions between the BP and glycaemia interventions.

Methods

Original ACCORD study design

The ACCORD and ACCORD MIND studies have been described previously [8, 9]. Briefly, ACCORD was a North American randomised, multicentre, double 2 × 2 factorial trial of 10,251 middle-aged and older participants with type 2 diabetes. All participants in the main ACCORD trial were enrolled in the glycaemia trial to compare a therapeutic strategy targeted to a HbA1c level of <6.0% (42.1 mmol/mol) (intensive therapy arm) vs a strategy that targeted HbA1c levels of 7.0–7.9% (53.0–62.8 mmol/mol) (standard therapy arm). The BP trial included 46.2% of all participants and compared a therapeutic strategy targeting a systolic BP (SBP) of <120 mmHg (intensive therapy) to one targeting an SBP of <140 mmHg (standard therapy). Participants meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria with an SBP of 130–180 mmHg and taking no more than three antihypertensives were eligible for the BP trial. The remaining participants (53.8% of the total sample) were assigned to the lipid trial. The lipid trial compared masked administration of placebo or fenofibrate on HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in persons with HDL-C levels of <2.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) achieved through study-supplied simvastatin.

In February 2008, an increased mortality risk in the intensive glycaemia intervention arm was reported, leading to the termination of that arm and transition of those participants to the standard glycaemic intervention protocol [19]. In the MIND subcohort, this resulted in an average treatment period of 40 months for those in the intensive glycaemia intervention group. The lipid and BP trials continued to the planned completion date in June 2009, providing 56 months of exposure to the BP or lipid interventions. Similar to the larger ACCORD trial, in ACCORD MIND there was excellent separation between treatment groups for HbA1c, SBP and HDL in the glucose, BP and lipid trials, respectively.

ACCORDION MIND study design

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the ACCORD MIND subcohort participants had to meet the following criteria at baseline: age ≥55 years; HbA1c ≥7.5% (≥58 mmol/mol); high risk for cardiovascular events due to prevalent cardiovascular disease (CVD) or additional cardiovascular risk factors; and no clinical evidence of cognitive impairment or dementia.

Ethics

All participants in ACCORD MIND and ACCORDION MIND provided informed consent, and both studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the sponsors and each clinical site was approved to collect additional cognitive and MRI outcomes beginning in June 2011.

Recruitment and follow-up

For the ACCORD MIND trial, participants were recruited between January 2001 and October 2005. Follow-up of ACCORD MIND ended in June 2009. The ACCORDION follow-up visits occurred from 1 May 2011 (approximately 24 months post-ACCORD MIND) through to 31 October 2014 (60 months post-ACCORD MIND).

One additional follow-up cognitive assessment was added, targeted to be at 80 months (mean 86 months, range 69–116 months from baseline), providing four measures of cognition over an average of 7 years. An additional MRI was also acquired at the targeted 80 month follow-up (mean 84 months, range 69–112 months from baseline), providing three measures of brain structure during the study period.

Cognitive function outcome measures

Cognitive function was assessed in ACCORDION MIND using the same methodology as in ACCORD MIND as described previously [9]. The primary cognitive outcome remained the DSST score, defined as the number of correctly completed symbols in 120 seconds [10]. Secondary cognitive outcomes were: (1) the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [20], reported as the sum of the number of words (0–15) recalled during the immediate-, short- and delayed-recall trials; (2) modified Stroop Colour-Word Test [21] reported as the interference score (a higher score indicates worse function); and (3) the 30-point Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [22] administered to assess global cognitive function and to provide a metric to compare the MIND cohort with other study groups. Additionally, the Physician’s Health Questionnaire [23] was administered to screen for depression, a frequent comorbidity in individuals with type 2 diabetes and a factor that also influences cognitive test performance. Participants who were unable to come into study centres for cognitive testing were offered the option of taking the validated Telephone Interview Cognitive Status (TICS) [24, 25], an adaptation of the MMSE that is relatively well-correlated with MMSE items.

Brain MRI outcome measures and acquisition

The primary MRI outcome remained the TBV, and the secondary MRI outcome was AWM. The MRI acquisition and processing in ACCORDION followed the previously described protocol for the ACCORD MIND substudy [9, 26, 27]. Monthly MRI quality control procedures followed the American College of Radiology’s (ACR’s) MRIQC programme (www.acr.org/quality-safety/accreditation/mri, accessed 2 May 2016). The performance of the MRI scanners was consistent across study sites and throughout the duration of the study as reflected by ACR phantom measurements that always met or exceeded study thresholds.

Analytical methods

The mean and standard deviation for continuous baseline characteristics, as well as the counts and percentages for discrete baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and without an ACCORDION DSST, and with and without an MRI. To investigate whether the separation of physiological measures was maintained after the trial, we plotted the mean and 95% CI for HbA1c, SBP, and HDL-C and triacylglycerol levels over the ACCORDION follow-up by respective intervention.

Cognitive function

The primary glycaemia hypothesis in ACCORDION MIND was tested within the framework of a repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with an unstructured covariance matrix using Proc Mixed of SAS (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Maximum likelihood (ML) was used to estimate fixed effects. The ML techniques accounted for the correlation of measures within individuals and the possibility that missing outcomes depended on either observed covariates or on previously observed outcomes (missing at random [MAR]) [28, 29].

To test the primary hypotheses, we compared randomised groups on the achieved mean change from baseline at the 20 month, 40 month and 80 month cognitive assessments. Our model for change included measurements from all cognitive assessment visits, terms for the baseline value of the outcome, the glycaemia intervention, factors used to stratify randomisation (prior history of CVD, clinical centre network (CCN), allocation to BP or lipid trial, randomisation to the intensive BP group, and randomisation to the fibrate lipid group), a time factor (20 month, 40 month or 80 month visit), and the interaction between the time factor and the glycaemia effect. The hypothesis test of the glycaemia effect at the 20 month, 40 month or 80 month visits was performed using a linear contrast to compare the mean changes between randomised groups at each visit.

To investigate whether the rate of decline within intervention groups was different during ACCORD vs ACCORDION, we also estimated change-point regression models for repeated measures to allow different slopes for the ACCORD and ACCORDION periods [30]. The 40 month measure was chosen as the change-point of the slope set to be at 40 months of follow-up and a compound symmetric covariance matrix was used [30]. Finally, we investigated whether the rate of decline in the intensive glycaemia arm was the same as that in the standard glycaemia group, within each of the ACCORD and ACCORDION study periods. To do this, we added interaction terms between the intervention groups and rate of decline in the specific time period to the models.

Models to test the BP and lipid interventions were similar to those described for the glycaemia interventions. The possible interactions between the BP and glycaemia interventions was tested by adding this term into the above models.

The secondary cognitive function outcomes were analysed using repeated measures models similar to those used for the DSST. Interactions between glycaemia and either BP or lipid intervention effects on cognitive function were investigated by adding two- and three-way interaction terms between the time effect and the intervention effects to the models. Within these models, linear contrasts were used to test for interaction effects at specific time points.

Brain MRI analyses

MRI measures, including TBV and secondarily, AWM, were analysed using a similar modelling approach to that used for cognitive function. As AWM was highly skewed in our data, it was log-transformed for the analysis (log (AWM+0.1)).

Missing outcomes sensitivity analysis

As we were not able to re-measure all ACCORD MIND participants in ACCORDION, the effects of missing data on the conclusions drawn in these analyses need to be understood. To gain insight into this effect we conducted three sensitivity analyses (see ESM Methods for further details).

Results

Participants

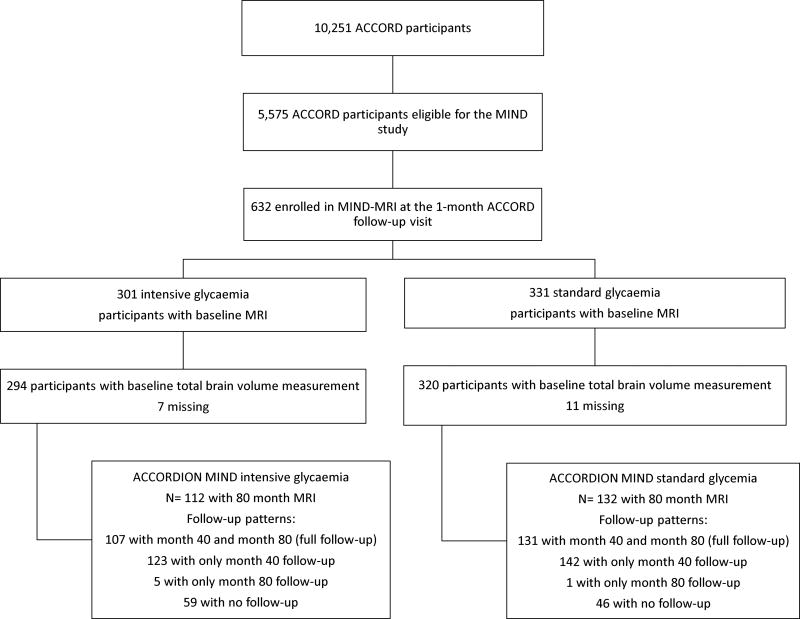

Of the 2572 (86% of baseline enrolment) surviving ACCORD MIND participants, 1962 (76%) consented to take part in the ACCORDION main study (not shown). Of these MIND participants, 1328 (68% of eligible; 52% of the baseline sample) completed the 80 month visit (Fig. 1). Of the 544 (89% of baseline enrolment) surviving participants enrolled in the MIND-MRI portion of the study, 432 (79%) consented to the ACCORDION main study (not shown). Of these, 292 (68% of eligible and 54% of all surviving ACCORD MIND participants) had an MRI at 80 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram for ACCORDION MIND cognitive function assessments

Fig. 2.

Consort diagram for ACCORDION MIND-MRI

On average, the cognitive tests in ACCORDION MIND were completed 47 ± 4 months (range 40–66) after the intensive glycaemia intervention was stopped, 31 ± 4 months (range 24–50) after final follow-up of the BP and lipid trials, 86 ± 8 months (range 69–116) after randomisation, and 46 ± 8 months (range 27–74) after the final ACCORD assessment at 40 months post-randomisation.

The mean age of the ACCORDION cohort at baseline was 62.1 ± 5.5 years, 43.1% were female and the mean duration of diabetes was 10.3 ± 7.0 years (Table 1). At baseline, participants missing the ACCORDION DSST measurement were slightly more likely to be female, less likely to be white, had lower education, a higher prevalence of previous CVD, were more likely to be current smokers and almost twice as likely to be uninsured. They also had a slightly higher mean HbA1c (8.4 ± 1.1 vs 8.2 ± 1.0; 68.3 vs 66.1 mmol/mol), and were less likely to be in the intensive glycaemic group and more likely to be in the BP trial than in the lipid trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics comparing participants with and without a DSST score at ACCORDION 80 month visit

| Overall (n=2977) | No M80 measurement (n=1649) |

M80 measurement complete (n=1328) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.5±5.8 | 62.8±6.0 | 62.1±5.5 |

| Sex, female | 1388 (46.6) | 815 (49.4) | 573 (43.1) |

| Intensive glycaemia arm | 1469 (49.3) | 785 (47.6) | 684 (51.5) |

| Subcohort | |||

| BP trial | 1439 (48.3) | 857 (52.0) | 582 (43.8) |

| Lipid trial | 1538 (51.7) | 792 (48.0) | 746 (56.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White only | 2074 (69.7) | 1095 (66.4) | 979 (73.7) |

| Spanish/hispanic | 212 (7.1) | 120 (7.3) | 92 (6.9) |

| Black, non-hispanic | 484 (16.3) | 302 (18.3) | 182 (13.7) |

| Asian, not hispanic or black | 67 (2.3) | 43 (2.6) | 24 (1.8) |

| Other | 140 (4.7) | 89 (5.4) | 51 (3.8) |

| Education | |||

| < High school graduate | 392 (13.2) | 262 (15.9) | 130 (9.8) |

| High school graduate/GED | 769 (25.8) | 462 (28.0) | 307 (23.1) |

| Some college/tech | 1027 (34.5) | 554 (33.6) | 473 (35.6) |

| College graduate or more | 789 (26.5) | 371 (22.5) | 418 (31.5) |

| Prior CVD | 869 (29.2) | 521 (31.6) | 348 (26.2) |

| Live with someone | 2320 (77.9%) | 1253 (76.0%) | 1067 (80.3%) |

| Uninsured | 516 (17.3%) | 361 (21.9%) | 155 (11.7%) |

| Alcohol >8 drinks per week | 257 (8.6%) | 115 (7.0%) | 142 (10.7%) |

| Depression | 872 (29.3%) | 503 (30.5%) | 369 (27.8%) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 1327 (44.6) | 726 (44.1) | 601 (45.3) |

| Former | 1295 (43.5) | 699 (42.5) | 596 (44.9) |

| Current | 352 (11.8) | 221 (13.4) | 131 (9.9) |

| SF-36 General Health | 36.9±12.8 | 37.4±13.3 | 36.3±12.1 |

| Diabetes duration | 10.4±7.3 | 10.5±7.6 | 10.3±7.0 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 8.3±1.1 (67.2) | 8.4±1.1 (68.3) | 8.2±1.0 (66.1) |

Data presented are mean ± SD or n (%)

The differences in characteristics between ACCORDION MIND participants with and without an MRI were very similar to those with and without complete DSST outcomes (Table 2). In addition, those without a follow-up MRI had longer duration of diabetes (10.1 ±7.5 vs 9.7 ± 6.8 years).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics comparing participants with and without an MRI at ACCORDION 80 month visit

| Overall (n=614) | No M80 MRI (n=322) | M80 MRI complete (n=292) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.4±5.7 | 62.7±6.1 | 62.0±5.3 |

| Sex, female | 273 (44.5) | 144 (44.7) | 129 (44.2) |

| Intensive glycaemia arm | 294 (47.9) | 159 (49.4) | 135 (46.2) |

| Subcohort | |||

| BP trial | 378 (61.6) | 202 (62.7) | 176 (60.3) |

| Lipid trial | 236 (38.4) | 120 (37.3) | 116 (39.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White only | 420 (68.4) | 213 (66.1) | 207 (70.9) |

| Spanish/hispanic | 39 (6.4) | 18 (5.6% | 21 (7.2) |

| Black, non-hispanic | 103 (16.8) | 55 (17.1) | 48 (16.4) |

| Asian, not hispanic or black | 9 (1.5) | 6 (1.9) | 3 (1.0) |

| Other | 43 (7.0) | 30 (9.3) | 13 (4.5) |

| Education | |||

| < High school graduate | 62 (10.1) | 41 (12.7) | 21 (7.2) |

| High school graduate/GED | 148 (24.1) | 79 (24.5) | 69 (23.6) |

| Some college/tech | 210 (34.2) | 113 (35.1) | 97 (33.2) |

| College graduate or more | 194 (31.6) | 89 (27.6) | 105 (36.0) |

| Prior CVD | 160 (26.1) | 97 (30.1) | 63 (21.6) |

| Live with someone | 468 (76.2) | 242 (75.2) | 226 (77.4) |

| Uninsured | 103 (16.8) | 64 (19.9) | 39 (13.4) |

| Alcohol >8 drinks per week | 56 (9.1) | 31 (9.6) | 25 (8.6) |

| Depression | 192 (31.3) | 106 (32.9) | 86 (29.5) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 275 (44.9) | 136 (42.4) | 139 (47.6) |

| Former | 258 (42.1) | 134 (41.7) | 124 (42.5) |

| Current | 80 (13.1) | 51 (15.9) | 29 (9.9) |

| SF-36 General Health | 37.0±12.9 | 37.2±13.1 | 36.7±12.7 |

| Diabetes duration | 9.9±7.2 | 10.1±7.5 | 9.7±6.8 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 8.2±1.0 (66.1) | 8.3±1.1 (67.2) | 8.1±0.9 (65.0) |

Data presented are mean ± SD or n (%)

Long-term effects of the glycaemia intervention

Separation of HbA1c measures

The substantial separation in mean HbA1c achieved between the treatment arms during ACCORD and ACCORD MIND was not sustained during ACCORDION MIND (6.5% intensive vs 7.6% standard [47.5 vs 59.6 mmol/mol] at 36 months, and 7.6% (59.6 mmol/mol) in both arms at the final ACCORDION MIND visit; see ESM Fig. 1).

Cognitive test scores

We found no significant difference between the two glycaemic intervention groups in the adjusted 80 month DSST mean change scores (Table 3), or in the mean change scores for the MMSE, RAVLT or Stroop tests, adjusting for prior history of CVD, CCN, allocation to BP or lipid trial, randomisation to the intensive BP group, and randomisation to the fibrate lipid group. The results for the MMSE outcome, including observations with the converted TICS-41 scores, were similar to the results from the original MMSE assessments (data not shown). The addition of baseline factors predictive of missing outcomes provided results that were consistent with the results from the primary analysis (data not shown). In addition, sensitivity subgroup analyses conducted among sites with ≥70% participation at 80 months revealed similar results for all cognitive analyses (ESM Table 1).

Table 3.

Glycaemia intervention effect on cognitive function outcome

| Endpoint | Time point | n | Glycaemia intervention | Difference in mean changesb |

p value for difference in mean change |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Intensivea | Standarda | |||||

| DSST | Baselinec | 2957 | 52.55 | 52.55 | ||

| 20 months | 2747 | 51.52 (51.10, 51.94) | 50.98 (50.56, 51.39) | |||

| 40 months | 2629 | 50.93 (50.51, 51.36) | 50.61 (50.18, 51.03) | |||

| 80 months | 1323 | 49.10 (48.52, 49.69) | 48.79 (48.19, 49.38) | |||

| 20 month change | 2747 | −1.03 (−1.45, −0.61) | −1.57 (−1.99, −1.16) | 0.54 (−0.04, 1.13) | 0.07 | |

| 40 month change | 2629 | −1.62 (−2.04, −1.19) | −1.94 (−2.37, −1.52) | 0.33 (−0.27, 0.93) | 0.29 | |

| 80 month change | 1323 | −3.45 (−4.03, −2.86) | −3.76 (−4.36, −3.17) | 0.32 (−0.52, 1.15) | 0.46 | |

| RAVLT | Baselinec | 2968 | 7.52 | 7.52 | ||

| 20 months | 2762 | 7.88 (7.79, 7.97) | 7.85 (7.76, 7.94) | |||

| 40 months | 2629 | 8.00 (7.90, 8.10) | 7.99 (7.90, 8.09) | |||

| 80 months | 1307 | 7.45 (7.32, 7.59) | 7.51 (7.38, 7.65) | |||

| 20 month change | 2762 | 0.36 (0.27, 0.45) | 0.33 (0.24, 0.42) | 0.03 (−0.10, 0.16) | 0.63 | |

| 40 month change | 2629 | 0.48 (0.38, 0.58) | 0.47 (0.38, 0.57) | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.14) | 0.92 | |

| 80 month change | 1307 | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.13) | −0.06 (−0.25, 0.13) | 0.54 | |

| Stroop | Baselinec | 2941 | 32.0 | 32.0 | ||

| 20 months | 2705 | 30.86 (30.19, 31.54) | 31.46 (30.78, 32.12) | |||

| 40 months | 2590 | 31.46 (30.70, 32.22) | 32.07 (31.32, 32.82) | |||

| 80 months | 1286 | 35.21 (34.14, 36.28) | 35.80 (34.71, 36.89) | |||

| 20 month change | 2705 | −1.14 (−1.81, −0.46) | −0.54 (−1.20, 0.12) | −0.60 (−1.54, 0.35) | 0.22 | |

| 40 month change | 2590 | −0.54 (−1.30, 0.22) | 0.07 (−0.68, 0.82) | −0.61 (−1.67, 0.45) | 0.26 | |

| 80 month change | 1286 | 3.21 (2.14, 4.28) | 3.80 (2.71, 4.89) | −0.59 (−2.12, 0.94) | 0.45 | |

| MMSE | Baselinec | 2977 | 27.39 | 27.39 | ||

| 20 months | 2777 | 27.27 (27.16, 27.37) | 27.27 (27.17, 27.37) | |||

| 40 months | 2654 | 27.04 (26.90, 27.18) | 27.05 (26.92, 27.19) | |||

| 80 months | 1320 | 26.96 (26.82, 27.11) | 27.00 (26.85, 27.14) | |||

| 20 month change | 2777 | −0.12 (−0.23, −0.02) | −0.12 (−0.22, −0.02) | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.14) | 0.94 | |

| 40 month change | 2654 | −0.35 (−0.49, −0.21) | −0.34 (−0.47, −0.20) | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.18) | 0.90 | |

| 80 month change | 1320 | −0.43 (−0.57, −0.28) | −0.39 (−0.54, −0.25) | −0.03 (−0.24, 0.17) | 0.75 | |

Least squares mean (95% CI). For DSST, RAVLT and MMSE a negative change value represents a decline in cognitive score; for the Stroop test, a positive change value represents a worsening score

Difference calculated as intensive minus standard arm mean changes

Baseline mean is the overall mean for both groups combined as measured pre-randomisation. This value is used to obtain the least squares mean estimates at follow-up. Models are adjusted for baseline outcome measure, visit and the factors used to stratify randomisation: second trial assignment (BP or lipid), randomised group allocation within the BP and lipid trials, CCN and history of CVD

MRI outcomes

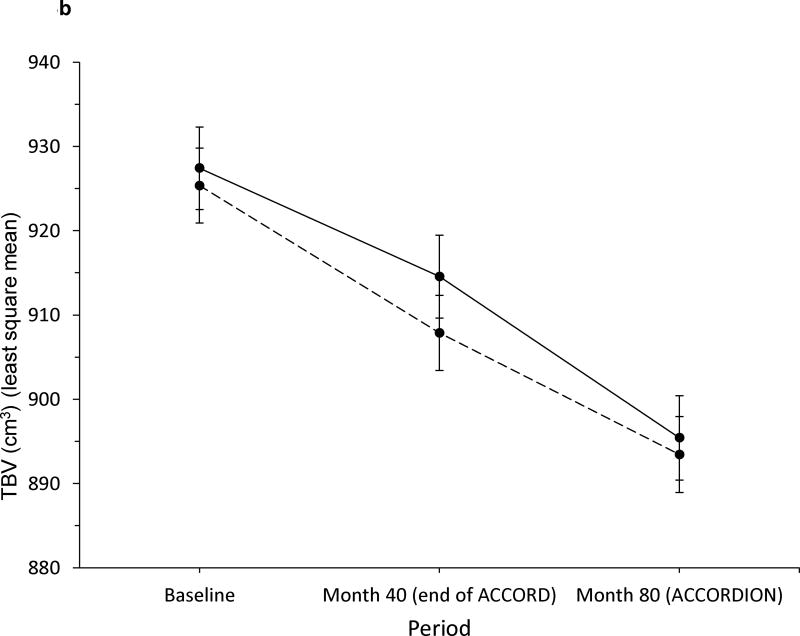

Although a significantly smaller decline in TBV was seen for the intensive vs standard glycaemic therapy group at 40 months (4.6 cm3 [95% CI 2.0, 7.3]) less compared with baseline; p=0.0006), it did not persist at 80 months (p=0.91). The interaction between glycaemia intervention and time was significant (p=0.02 for equality of 40- and 80 month effects). Likewise, although logAWM was significantly higher in the intensive glycaemic therapy group at 40 months (p=0.01), this difference did not persist at 80 months (p=0.41) (Table 4) and the interaction with time was not significant (p=0.30). Additionally, at the sites with ≥70% participation at 80 months, results for all MRI analyses were similar (ESM Table 2).

Table 4.

Glycaemia intervention effects on MRI outcomes

| Endpoint | Time point | n | Glycaemia intervention | Difference in mean changesb |

p value for difference in mean change |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Intensivea | Standarda | |||||

| TBV, cm3 | Baselinec | 614 | 927.5 | 927.5 | ||

| 40 months | 503 | 914.4 (912.4, 916.3) | 909.7 (907.9, 911.5) | |||

| 80 months | 292 | 894.9 (892.3, 897.6) | 894.7 (892.3, 897.2) | |||

| 40 month change | 503 | −13.1 (−15.1, −11.2) | −17.8 (−19.6, −16.0) | 4.6 (2.0, 7.3) | 0.0006 | |

| 80 month change | 292 | −32.6 (−35.2, −29.9) | −32.8 (−35.2, −30.3) | 0.2 (−3.4, 3.8) | 0.91 | |

| logAWMd | Baselinec | 614 | −0.03 | −0.03 | ||

| 40 months | 503 | 0.64 (0.58, 0.70) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.59) | |||

| 80 months | 292 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.95) | 0.81 (0.73, 0.89) | |||

| 40 month change | 503 | 0.67 (0.61, 0.73) | 0.57 (0.52, 0.62) | 0.10 (0.02, 0.18) | 0.014 | |

| 80 month change | 292 | 0.89 (0.80, 0.98) | 0.84 (0.76, 0.92) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | 0.41 | |

Least squares mean (95% CI). For TBV, a negative change value represents a decline in volume in cm3

Difference calculated as intensive minus standard arm mean changes

Baseline mean is the overall mean for both groups combined as measured pre-randomisation. This value is used to obtain the least squares mean estimates at follow-up. Models are adjusted for baseline outcome measure, visit and the factors used to stratify randomisation: second trial assignment (BP or lipid), randomised group allocation within the BP and lipid trials, CCN and history of CVD

Transformation: log(AWM+0.1)

Comparisons of ACCORD and ACCORDION rates of change

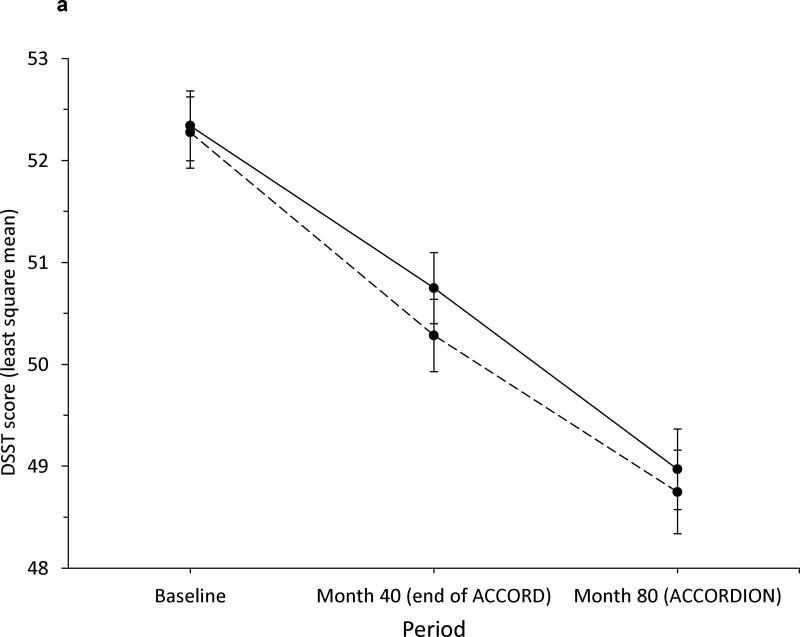

Within intervention groups, there was no evidence of a different annual rate of decline in DSST between the ACCORD and ACCORDION periods (intensive glycaemia: −0.48 and −0.46 DSST units/year, respectively, p=0.90; standard glycaemia: −0.60 and 0.40 DSST units/year, respectively, p=0.10; see Fig. 3a). The total decline in DSST score of ~3.5 points in both groups over 80 months was −0.23 standard deviations from baseline. Additionally, the rates of decline were not significantly different between intensive and standard glycaemia groups within each period (ACCORD period p=0.20; ACCORDION period p=0.56). In contrast, we did find significant differences in the rate of TBV decline during the ACCORD and ACCORDION periods (intensive glycaemia: −3.86 and −5.34 cm3/year, respectively, p=0.03; standard glycaemia: −5.24 and −4.03 cm3/year, respectively, p=0.02; see Fig. 3b). However, these changes were in the reverse direction, essentially countering the previous apparent beneficial effect on TBV of the intensive vs standard glycaemic treatment. This reversal is also captured in the significant differences in rate of TBV loss between the two groups within each period (ACCORD period significantly less decline in the intensive glycaemic group p=0.002; ACCORDION period significantly less decline in the standard group p=0.014).

Fig. 3.

Rate of change in (a) DSST score and (b) TBV (in cm3) during ACCORD MIND and ACCORDION MIND. Solid line, intensive arm; dashed line, standard arm. Error bars indicate 95% CI

Long-term effects of the BP and lipid interventions

Separation of BP and lipid measures

The separations in BP and lipid treatment targets that were achieved during ACCORD (ESM Figs 2 [SBP], 3 [HDL] and, 4 [triacylglycerol]) were not sustained during ACCORDION.

Cognitive test scores

There were no significant differences in adjusted mean change in DSST scores at 80 months or for the MMSE, RAVLT or Stroop tests (ESM Table 3) between intensive vs standard BP therapy or between the fibrate vs placebo lipid groups. However, when missing MMSE scores were replaced by converting TICS-41 scores to MMSE scores, there was a significant, but clinically negligible, difference in adjusted mean change in MMSE scores at 80 months (p=0.047) between the fibrate (−0.21 [95% CI −0.39, −0.03]) vs placebo (0.06 [95% CI −0.13, 0.25]) lipid groups, but not between the BP arms (results not shown). In addition, in sensitivity analyses that added depression to the primary models for each cognitive test score there was no appreciable change in any of the glycaemia, BP or lipid intervention results. There was also no significant interaction between the glycaemia and BP arms for any of the cognitive tests at any visit (ESM Table 4).

MRI outcomes

Despite previous results of a significantly larger decline in TBV in the intensive BP therapy vs standard BP therapy group at 40 months (−4.5 cm3 [95% CI −7.9, −1.2]; p=0.01) [10], there was no significant difference in TBV decline between the groups at 80 months. TBV declined by –32.4 cm3 in the intensive group and –34.4 cm3 in the standard group (p = 0.29) (ESM Table 5). There was also no significant interaction between the glycaemic and BP arms on brain MRI measures for TBV or logAWM at 80 months (ESM Table 6); thus the apparent protective effect of the interaction of the intensive glycaemic treatment protocol with standard BP therapy at 40 months did not persist.

Discussion

We found no long-term effects of the intensive glycaemic, BP or lipid interventions on cognition or brain structure outcomes at 80 months follow-up in ACCORDION MIND. Most noteworthy is the lack of a sustained effect on TBV of any of the treatment arms, despite significant MRI findings at 40 months. Specifically, at 80 months of follow-up there was no longer evidence for less atrophy associated with intensive glycaemic therapy, or increased atrophy associated with intensive BP control nor any persistence of an interactive effect for the combination of standard antihypertensive therapy plus intensive glycaemic control being associated with the least atrophy. However, the lack of any long-term effect also means the intensive treatment arms did not have long-lasting detrimental effects on cognition or TBV, despite the overall increased risk of mortality in the intensive glycaemic group that led to early ACCORD termination.

We sought to determine whether there was a long-term effect of the initial glycaemic intervention because previous studies in people with diabetes, including the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) and DCCT [18, 31], had demonstrated a delayed effect of glycaemic control on microvascular outcomes. In addition, the initial ACCORD glycaemia results showed a benefit in some microvascular outcomes, including delayed onset of albuminuria, some measures of neuropathy (loss of ankle jerk and light touch) and cataract surgery (adjusted OR 0.89 [95% CI 0.80, 0.99]; p=0.03) [32]. The ACCORDION EYE study also recently reported a delayed beneficial effect of a mean of 3.7 years of intensive glycaemic control on the progression of diabetic retinopathy during the 8-year follow-up in ACCORDION Eye (n=1310) [33]. Diabetic retinopathy progressed in 5.8% of individuals in the intensive glycaemic treatment group vs 12.7% in the standard group (adjusted OR 0.42 [95% CI 0.28, 0.63]; p<0.0001). Therefore, we hypothesised that we might observe a delayed beneficial effect on cognition if there were metabolic changes induced by the glycaemic intervention, and that the difference in TBV would be maintained or increased.

There may be several explanations for the lack of observed long-term effects in ACCORDION. Importantly, the substantial differences in therapeutic targets of each of the three interventions (glycaemic, BP and lipid) were not sustained during ACCORDION. The provision of free medications and frequent follow-up clinic visits during the study intervention may have reinforced treatment compliance and consequently treatment arm separation. The substantial loss to follow-up at 80 months limited power to discern differences in outcomes, even if effects had been sustained. In addition, participants with the greatest risk for cognitive change and TBV decline were more likely to miss the DSST at 80 months; on average, they were less educated, of non-white race/ethnicity, and had a longer duration of diabetes, higher HbA1c levels and more CVD, all of which are factors known to impact on the trajectory of cognitive decline [34–37]. Therefore, there was a bias towards a healthier cohort. However, our missing data sensitivity analyses suggest that this bias would not substantially alter the conclusions.

The lack of inclusion of a usual care glycaemic, BP and lipid control groups may have also hampered our ability to evaluate the true short- and long-term impact of intensive risk factor reduction on brain outcomes. Furthermore, we cannot generalise our findings to other groups beyond healthier people with long-term type 2 diabetes, relatively poorly controlled HbA1c levels (mean 8.3% [67.2 mmol/mol]) and at high risk of CVD, with a mean baseline MMSE score >27.

The 10-year average duration of type 2 diabetes at trial entry may have been too long, and the negative vascular metabolic memory generated too strong for even the intensive ACCORD glycaemic intervention to reverse changes already present in the brain [38]. In comparison, the UKPDS was conducted in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, and thus with a much shorter exposure to diabetes [17]. Participants in the DCCT long-term follow-up study, EDIC (the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications), had type 1 diabetes and were younger (mean age 47.7 years at EDIC baseline) [18, 31]. Importantly, our results point to the need to define what constitutes a sufficient treatment time interval to provide sustained post-treatment effects given a specific diabetes duration [38].

The strengths of ACCORDION MIND include its prospective design within a well-executed randomised clinical trial in a large type 2 diabetes population, attainment of substantial treatment endpoint separation at the end of the trial between treatment groups for the three interventions, the high degree of data capture until 40 months, and the ability to capture cognitive and anatomic brain outcomes.

Conclusion

In the ACCORDION MIND study, we found no long-term effects of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia, BP or lipid levels on cognitive function or TBV at 80 months follow-up, approximately 4 years after the intensive glycaemia intervention was terminated, and after substantial separations in treatment targets in all three intervention groups in ACCORD MIND. These findings, in addition to the lack of significant cognitive outcomes in ACCORD MIND at 40 months, do not support aggressive glycaemic, BP and lipid control to prevent cognitive decline in older people who have had type 2 diabetes for, on average, 10 years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank M. Bartkoske, and S. Pederson, both at the Berman Center for Clinical Research, and N. Booth, at the Chronic Disease Research Group, all at the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis for their assistance in manuscript preparation.

Funding ACCORD was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contracts N01-HC-95178, N01-HC-95179, N01-HC-95180, N01-HC-95181, N01-HC-95182, N01-HC-95183, N01-HC-95184, IAA#Y1-HC-9035 and IAA#Y1- HC-1010. ACCORDION MIND was funded through an intra-agency agreement between the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and NHLBI (AG-0008), NIA contract (HSN271201000023C) and the NIA Intramural Research Program. Other components of the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute of Diabetes, and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Eye Institute, contributed funding. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded ACCORD substudies of cost-effectiveness and health-related quality of life. General Clinical Research Centers provided support at many sites.

The following companies provided study medications, equipment or supplies: Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL, USA); Amylin Pharmaceutical (San Diego, CA, USA); AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP (Wilmington, DE, USA); Bayer HealthCare LLC (Tarrytown, NY, USA); Closer Healthcare Inc. (Tequesta, FL, USA); GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals (Philadelphia, PA, USA); King Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Bristol, TN, USA); Merck & Co., Inc. (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA); Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (East Hanover, NJ, USA); Novo Nordisk, Inc. (Princeton, NJ, USA); Omron Healthcare, Inc. (Schaumburg, IL, USA); Sanofi U.S. (Bridgewater, NJ, USA); Schering-Plough Corporation (Kenilworth, NJ, USA). The donors of medications and devices had no role in the study design, data accrual and analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- ACCORD

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes

- ACCORD MIND

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Memory in Diabetes

- AWM

Abnormal white matter volume

- CCN

Clinical centre network

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DSST

Digit Symbol Substitution Test

- EDIC

Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications

- HDL-C

HDL-cholesterol

- M80

80 month follow-up

- MAR

Missing at random

- ML

Maximum likelihood

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- NIA

National Institute on Aging

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- RAVLT

Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TBV

Total brain volume

- TICS

Telephone Interview Cognitive Status

- UKPDS

UK Prospective Diabetes Study

Footnotes

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00182910

Duality of interest The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author contributions All authors made substantial contributions to (1) conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) gave final approval of the version to be published. JDW and MEM are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Biessels GJ, Stakenborg S, Brunner E, Brayne C, Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez A, Wolfsgruber S, Lange C, et al. Elevated HbA1c is associated with increased risk of incident dementia in primary care patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;44:1203–1212. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jongen C, van der Grond J, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ, Viergever MA, Pluim JP. Automated measurement of brain and white matter lesion volume in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1509–1516. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias PK, Elias MF, D'Agostino RB, et al. NIDDM and blood pressure as risk factors for poor cognitive performance The Framingham Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1388–1395. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.9.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt R, Launer LJ, Nilsson LG, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in diabetes: the Cardiovascular Determinants of Dementia (CASCADE) study. Diabetes. 2004;53:687–692. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahtiluoto S, Polvikoski T, Peltonen M, et al. Diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia: a population-based neuropathologic study. Neurology. 2010;75:1195–1202. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d7f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wardlaw JM, Allerhand M, Doubal FN, et al. Vascular risk factors, large-artery atheroma, and brain white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2014;82:1331–1338. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buse JB, Bigger JT, Byington RP, et al. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial: design and methods. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:21i–33i. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson JD, Miller ME, Bryan RN, et al. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Memory in Diabetes Study (ACCORD-MIND): rationale, design, and methods. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:112i–122i. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wechsler D. The Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernooij MW, de Groot M, van der Lugt A, et al. White matter atrophy and lesion formation explain the loss of structural integrity of white matter in aging. Neuroimage. 2008;43:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox NC, Schott JM. Imaging cerebral atrophy: normal ageing to Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2004;363:392–394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15441-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnick S, Inaba K, Karamanos E, et al. Clinical relevance of magnetic resonance imaging in cervical spine clearance: a prospective study. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:934–939. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Harten B, de Leeuw FE, Weinstein HC, Scheltens P, Biessels GJ. Brain imaging in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2539–2548. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Launer LJ, Miller ME, Williamson JD, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomised open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:969–977. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White NH, Sun W, Cleary PA, et al. Prolonged effect of intensive therapy on the risk of retinopathy complications in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: 10 years after the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1707–1715. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houx PJ, Jolles J, Vreeling FW. Stroop interference: aging effects assessed with the Stroop Color-Word Test. Exp Aging Res. 1993;19:209–224. doi: 10.1080/03610739308253934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein MF. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology & Behavioral Neurology. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fong TG, Fearing MA, Jones RN, et al. Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status: creating a crosswalk with the Mini-Mental State Examination. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldszal AF, Davatzikos C, Pham DL, Yan MX, Bryan RN, Resnick SM. An image-processing system for qualitative and quantitative volumetric analysis of brain images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:827–837. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199809000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lao Z, Shen D, Liu D, et al. Computer-assisted segmentation of white matter lesions in 3D MR images using support vector machine. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molenberghs G, Kenward MG, editors. Missing data in clinical studies. Chichester: Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudson DJ. Fitting segmented curves whose join pointes to have to be estimated. JASA. 1966;61:1097–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin CL, Waberski BH, Pop-Busui R, et al. Vibration perception threshold as a measure of distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: results from the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2635–2641. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ismail-Beigi F, Craven T, Banerji MA, et al. Effect of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia on microvascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the ACCORD randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:419–430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60576-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Follow-On (ACCORDION) Eye Study Group and the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Follow-On (ACCORDION) Study Group. Persistent effects of intensive glycemic control on retinopathy in type 2 diabetes in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) follow-on study. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1089–1100. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaffe K, Falvey C, Harris TB, et al. Health ABC Study. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: prospective study. BMJ. 2013;19:347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rawlings AM, Sharrett AR, Schneider AL, et al. Diabetes in midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:785–793. doi: 10.7326/M14-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haring B, Leng X, Robinson J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline in postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000369. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bianchi C, Miccoli R, Del PS. Hyperglycemia and vascular metabolic memory: truth or fiction? Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:403–410. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.