We systematically evaluate potential platforms for site-specifically incorporating two distinct noncanonical amino acids into proteins expressed in mammalian cells with optimal fidelity and efficiency – a technology that will have many enabling applications.

We systematically evaluate potential platforms for site-specifically incorporating two distinct noncanonical amino acids into proteins expressed in mammalian cells with optimal fidelity and efficiency – a technology that will have many enabling applications.

Abstract

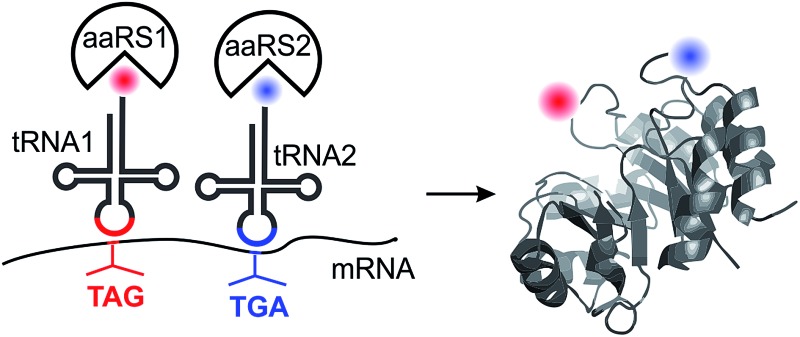

The ability to site-specifically incorporate two distinct noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) into the proteome of a mammalian cell with high fidelity and efficiency will have many enabling applications. It would require the use of two different engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS)/tRNA pairs, each suppressing a distinct nonsense codon, and which cross-react neither with each other, nor with their counterparts from the host cell. Three different aaRS/tRNA pairs have been developed so far to expand the genetic code of mammalian cells, which can be potentially combined in three unique ways to drive site-specific incorporation of two distinct ncAAs. To explore the suitability of using these combinations for suppressing two distinct nonsense codons with high fidelity and efficiency, here we systematically investigate: (1) how efficiently the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs suppress the three different nonsense codons, (2) preexisting cross-reactivities among these pairs that would compromise their simultaneous use, and (3) whether different nonsense-suppressor tRNAs exhibit unwanted suppression of non-cognate stop codons in mammalian cells. From these comprehensive analyses, two unique combinations of aaRS/tRNA pairs emerged as being suitable for high-fidelity dual nonsense suppression. We developed expression systems to validate the use of both combinations for the site-specific incorporation of two different ncAAs into proteins expressed in mammalian cells. Our work lays the foundation for developing powerful applications of dual-ncAA incorporation technology in mammalian cells, and highlights aspects of this nascent technology that need to be addressed to realize its full potential.

Introduction

Expanding the genetic code of a mammalian cell enables site-specific incorporation of new chemistries into its proteome, which can be used in powerful new ways to probe and engineer protein structure and function.1–6 This technology relies on the use of an engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS)/tRNA pair capable of charging a desired noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) in response to a nonsense or a frameshift codon. The ability to further advance this technology for the incorporation of two distinct ncAAs into the proteome of a mammalian cell with high fidelity and efficiency will spur many powerful applications, such as enabling site-specific attachment of two optical probes to study protein dynamics.7–10 To achieve this, each of the two ncAAs must be delivered by a distinct aaRS/tRNA pair that do not cross react with their counterparts from the host cell (i.e., orthogonal), nor with each other (mutually orthogonal). In E. coli, the M. jannaschii derived tyrosyl pair and the Methanosarcinaderived pyrrolysyl pair have been used together to achieve site-specific incorporation of two distinct ncAAs in response to two nonsense codons (e.g., TAG and TAA),8,9 or a nonsense and a frameshift codon (e.g., TAG and AGGA).10,11 In contrast, the technology enabling site-specific dual ncAA incorporation into proteins expressed in mammalian cells remains at its infancy.

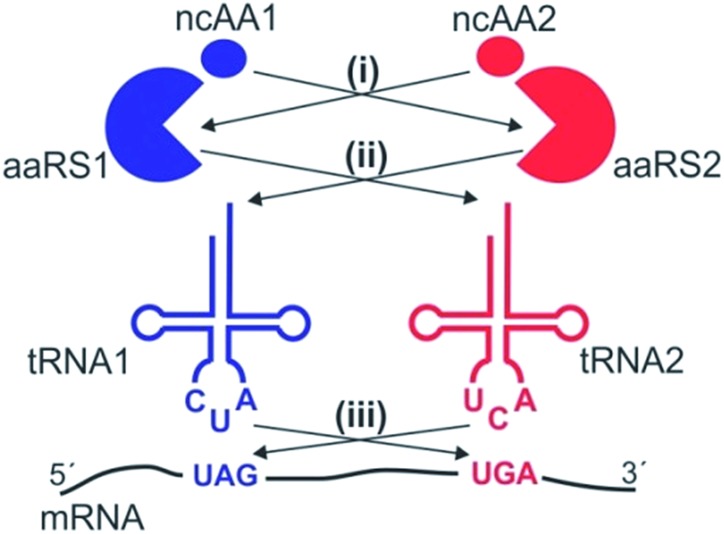

Three different aaRS/tRNA pairs have been developed so far for the genetic code expansion of mammalian cells: a tyrosyl (EcTyr)12 and a leucyl (EcLeu)13 pair derived from E. coli, and the archaeal pyrrolysyl (Pyl) pair.1–3,14 Even though it should be theoretically possible to use these pairs in three unique combinations to incorporate two distinct ncAAs into proteins expressed in mammalian cells, whether all of these combinations are indeed suitable remains unclear. The suppression systems driving the incorporation of two distinct ncAAs can cross-react at several levels (Fig. 1): (i) an aaRS may charge the substrate ncAA of the other aaRS, (ii) an aaRS may charge the non-cognate tRNA, and (iii) a suppressor tRNA may recognize the non-cognate nonsense codon. Furthermore, all three available aaRS/tRNA pairs have been developed as TAG suppressors, and their ability to suppress other nonsense codons – essential to achieve site-specific incorporation of two different ncAAs – remains largely uncharacterized. Although the Pyl pair was recently shown to be capable of TAA suppression in mammalian cells, and was used in conjunction with a TAG-suppressing EcTyr pair for dual ncAA incorporation for the first time,15 whether this system is free from any of these aforementioned cross-reactivities was not carefully analyzed, bringing into question its suitability for high-fidelity dual suppression.

Fig. 1. Potential cross-reactivities between two nonsense suppression systems. (i) One aaRS may charge the substrate ncAA of the other aaRS. (ii) One aaRS may charge the non-cognate tRNA. (iii) One nonsense suppressor tRNA may charge a non-cognate nonsense codon.

Here we report a systematic characterization of the three aforementioned orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs to better define the current scope of site-specific incorporation of two different ncAAs into proteins in mammalian cells. Our detailed analyses reveal critical guidelines for designing high-fidelity dual nonsense suppression systems in mammalian cells, and identify the combinations of EcTyr + Pyl, or EcLeu + Pyl pairs, suppressing TAG and TGA, as suitable candidates. We further demonstrate the feasibility of using both of these dual-nonsense suppression systems to enable site-specific incorporation of a various combinations of two distinct ncAAs into reporter proteins, including ones that enable chemoselective protein modification.

Results

Comparing the nonsense-suppression activities of the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs in mammalian cells

Site-specific incorporation of two different ncAAs is contingent upon the availability of two unique noncoding codons and mutually orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs that suppress them. As the three available pairs for mammalian genetic code expansion were all originally adapted as TAG suppressors,12–14 suppression systems for other “blank” codons must be first developed to achieve dual suppression. Besides TAG, the two other nonsense codons, as well as the quadruplet “frameshift” codons, are potential candidates for developing additional suppression systems. However, quadruplet suppression in mammalian cells remains significantly less efficient relative to nonsense suppression.16 We took a systematic approach to evaluate how efficiently the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs suppresses each of the three nonsense codons, to better characterize all available options for creating dual suppression systems. To rapidly evaluate these activities, we first established a modular transfection system for nonsense suppression in mammalian cells, where the genes encoding the nonsense suppressor tRNA, the aaRS, and an EGFP reporter harboring a nonsense codon at a permissive site, are encoded in three separate plasmids. This modular system enables facile testing of different cognate and non-cognate combinations of aaRS:tRNA:reporter to readily compare suppression activities for different codons, and to identify potential cross-reactivities.

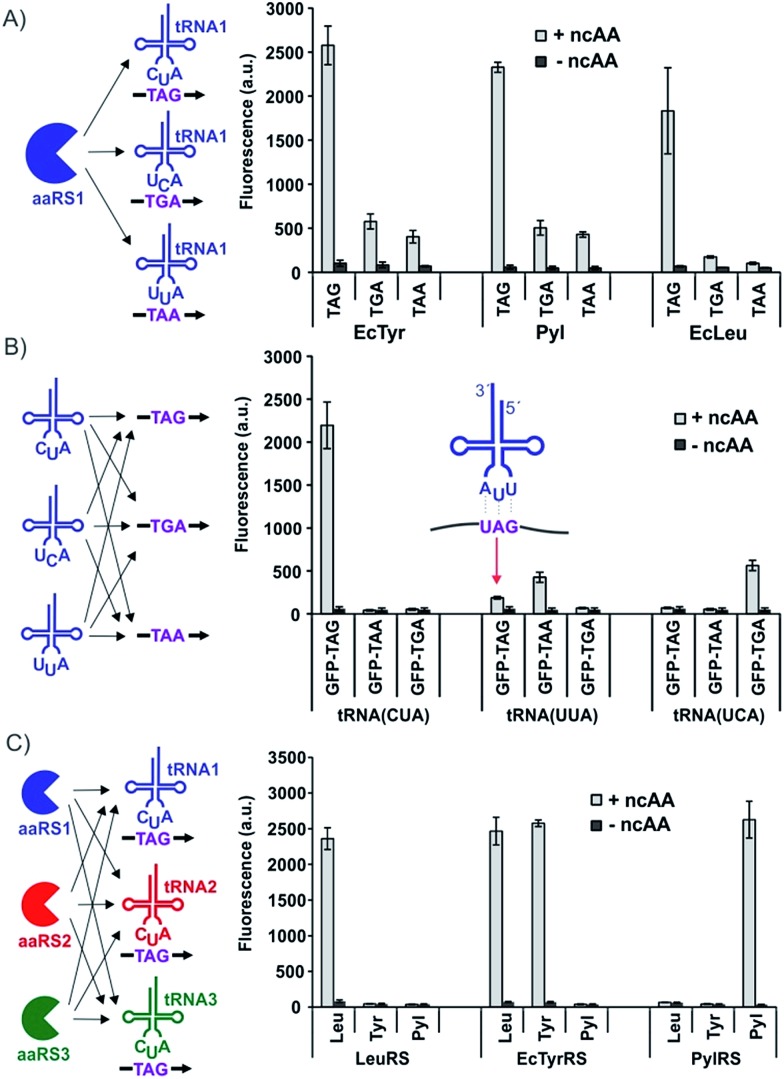

To characterize the different nonsense suppression activities of the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs, each aaRS plasmid was separately co-transfected into HEK293T cells with the three distinct nonsense suppressors of its cognate tRNA, as well as an EGFP-reporter harboring the matching nonsense codon at a permissive site (Fig. 3A). The relative expression levels of full-length EGFP, which can be easily measured using its characteristic fluorescence in the cell-free extract, were used to quantify the nonsense suppression efficiencies (Fig. 3A). For the EcTyr system, we used a previously described polyspecific aaRS and O-methyltyrosine (OMeY, 1; Fig. 2) as its substrate.17 For the Pyl system, we used the wild-type M. barkeri derived aaRS and Nε-boc-lysine (BocK, 6) as the substrate.14,17 A polyspecific EcLeuRS was used for the EcLeu system, and 2-aminocaprylic acid (Cap, 5) was used as its substrate.18 While all three pairs exhibited robust and similar levels of TAG-suppression activities, decoding efficiencies of TGA and TAA were significantly lower (Fig. 3A and S1†). For Pyl- and EcTyr-derived suppressors, expression levels of EGFP-39-TGA and EGFP-39-TAA reporters were 4–6 fold lower relative to EGFP-39-TAG. Suppression of TGA and TAA by the EcLeu pair was barely detectable over background, suggesting that its potential use in dual suppression will be restricted to TAG suppression. These results provide the much needed guidelines for optimal codon selection when designing dual suppression experiments in mammalian cells using the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs.

Fig. 3. Evaluation of the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs to identify optimal dual nonsense suppression systems. Full-length EGFP reporter expression, measured by its characteristic fluorescence in cell-free extract, is reported in each case to represent nonsense suppression efficiency. Each data point represents an average of three replicates; error bars represent S.D. (A) Each aaRS is cotransfected with three different nonsense suppressors of its cognate tRNA and the appropriate EGFP-mutant to evaluate how well each pair suppresses the three different nonsense codons. (B) Each of the three nonsense suppressing variants of tRNAPyl is co-transfected with three different nonsense mutants of EGFP, as well as PylRS, to evaluate if any of the nonsense suppressors can recognize a non-cognate nonsense codon. The basis of non-cognate UAG suppression by tRNAPylUUAvia wobble pairing is shown in the inset. (C) Each of the three different aaRSs was cotransfected with the three different TAG-suppressing tRNAs, as well as EGFP-39-TAG, to identify potential aminoacylation of non-cognate tRNAs.

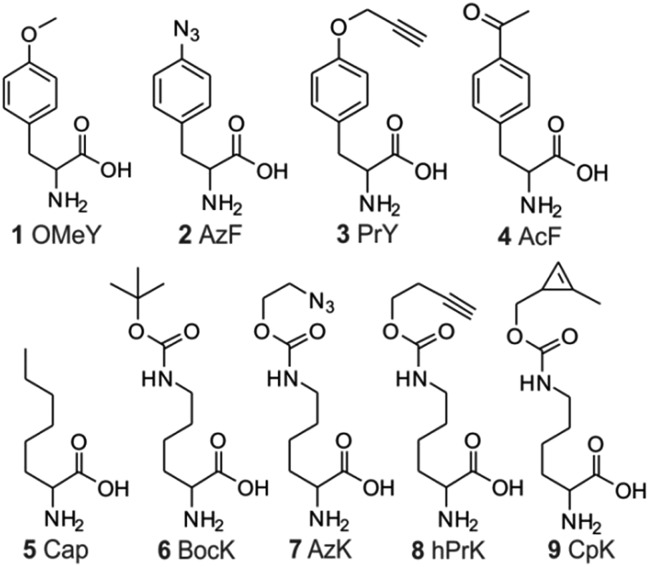

Fig. 2. Structures of ncAAs used in this work.

Evaluating potential mischarging of non-cognate stop codons by three different nonsense-suppressor tRNAs

TAG is the obvious choice to drive the incorporation of one of the ncAAs for dual incorporation, since all three pairs suppress it with high efficiency. To identify an optimal second codon to be used in combination with TAG, it is important to rule out any cross-reactivity at the level of codon-anticodon recognition. We used our modular three-plasmid transfection system to identify the existence of any such cross-reactivity among the three nonsense suppressor tRNAs. Three plasmids, encoding the three different nonsense suppressors of tRNAPyl, were each separately cotransfected with the three different nonsense mutants of the EGFP reporter, as well as the plasmid encoding wild-type PylRS (Fig. 3B). In the absence of any mischarging of non-cognate nonsense codons by these suppressors, EGFP fluorescence should only be expected when a suppressor tRNA plasmid is combined with the reporter harboring its cognate nonsense codon. However, we observed a substantial level of TAG suppression by tRNAPylUUA (TAA suppressor), likely due to wobble pairing (Fig. 3B and S2†).19 The TAA-suppressing tRNAEcTyrUUA also exhibited the same behavior (Fig. S3†), which indicates that non-cognate TAG suppression is a general property of TAA-suppressing tRNAs, precluding the TAG + TAA codon combination for high-fidelity dual suppression. Since no such cross-reactivity was found between the TAG and TGA suppression systems, our results identify TAG + TGA as an optimal codon combination for incorporating two different ncAA into proteins in mammalian cells with high fidelity and efficiency.

Evaluating potential cross-reactivities among three aaRS/tRNA pairs

If the two different aaRS/tRNA pairs driving the incorporation of two distinct ncAAs cross-react with each other, the fidelity of the platform will be compromised. To identify any such cross-reactivity among the three available aaRS/tRNA pairs, we again took advantage of our modular three-plasmid transfection system described above. The aaRS associated with each pair was separately cotransfected into HEK293T cells with the three different TAG-suppressing tRNAs, as well as an EGFP reporter harboring a TAG codon (Fig. 3C). If all three pairs were mutually orthogonal, then EGFP fluorescence should only be observed when an aaRS is co-transfected with its cognate tRNA. While this was largely the case, robust EGFP fluorescence was observed when EcTyrRS was co-transfected with tRNAEcLeuCUA (Fig. 3C and S4†). Although this cross-reactivity was unexpected, given both pairs are derived from the same organism, it is not without precedent. It has been previously shown that altering the anticodon of various E. coli tRNAs makes them substrates for non-cognate E. coli aaRSs.20–22 These results identify the combination of EcTyr and EcLeu pairs as unsuitable for high-fidelity dual suppression in mammalian cells, but suggest that the other two combinations, EcTyr + Pyl and EcLeu + Pyl, can be used for this purpose.

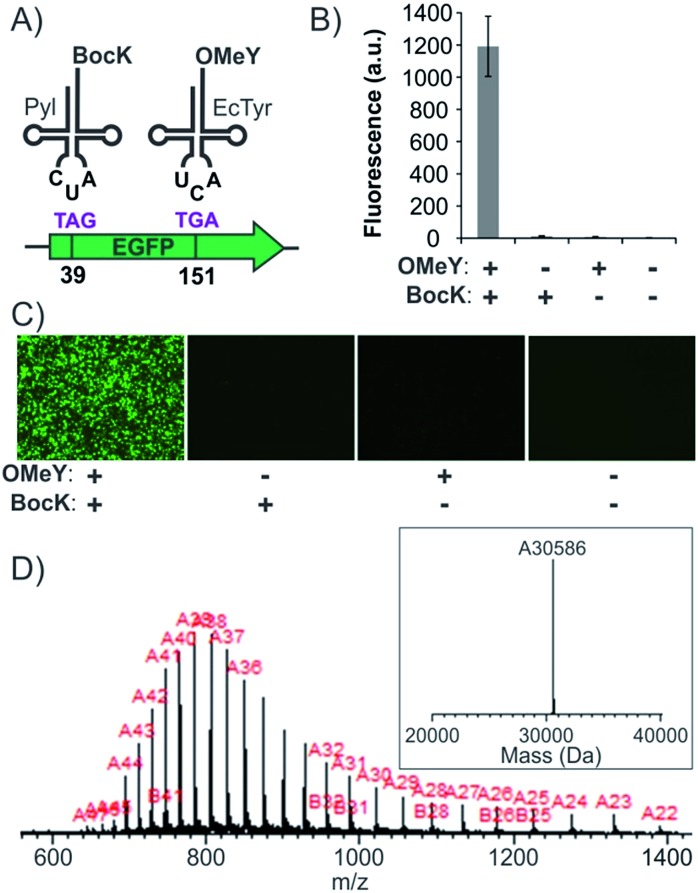

Dual suppression using Tyr and Pyl pairs

The systematic analyses of the available suppression systems presented above facilitate the identification of suitable combinations of mutually orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs, as well as nonsense codons, for efficient and accurate dual suppression in mammalian cells. Next, we focused on developing expression systems for these potential combinations to achieve site-specific incorporation of two ncAAs into proteins. The EcTyr and Pyl pairs were previously used as TAG and TAA suppressors, respectively, for site-specific incorporation of two different ncAAs in mammalian cells.15 However, we show here that this codon combination is not optimal due to an intrinsic cross-reactivity described above. To create a higher-fidelity dual suppression system using the TAG + TGA codon combination, we needed to address which codon will be assigned to which pair. Since the EcTyr and Pyl pairs suppress TAG and TGA at similar levels, it was not immediately obvious what would be an optimal codon assignment. Consequently, we created plasmid systems to experimentally evaluate both possibilities. Expression cassettes for the EcTyr- and Pyl-aaRS/tRNA pairs were incorporated into two separate pAcBac plasmids (Fig. S5†).17,23 Since tRNA expression level limits nonsense-suppression efficiency, a multicopy-tRNA cassette was included in each plasmid.23,24 For both EcTyr and Pyl, two different plasmids were created: one encoding the TAG suppressor tRNA, the other encoding the corresponding TGA suppressor. A CAG promoter-driven EGFP reporter, harboring a TAG and a TGA at positions 39 and 151, respectively, was also introduced into the pAcBac plasmid harboring the EcTyr system (Fig. S5A†). Plasmids encoding EcTyrTAG + PylTGA or EcTyrTGA + PylTAG suppression systems were cotransfected into HEK293T cells and the expression of the EGFP-39TAG-151TGA reporter from the EcTyr-plasmid was analyzed by the appearance of the characteristic EGFP fluorescence. Robust EGFP expression was only observed when 1 mM of both BocK and OMeY were both included in the medium (Fig. 4B and C). The EcTyrTGA + PylTAG combination was found to yield higher levels of reporter expression in general relative to EcTyrTAG + PylTGA (Fig. S6†). The full-length reporter protein was isolated using a C-terminal polyhistidine tag by immobilized metal ion chromatography (IMAC) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS analysis (Fig. 4D), which confirmed a mass consistent with the incorporation of the desired ncAAs. Efficiency of dual ncAA incorporation into EGFP-39TAG-151TGA reporter was found to be roughly 7.5% relative to the corresponding wild-type EGFP reporter (no nonsense mutation; Table 1).

Fig. 4. Site-specific incorporation of BocK and OMeY into EGFP-39-TAG-151-TGA. (A) The scheme of dual suppression. (B) Expression of the full-length EGFP reporter, measured by its characteristic fluorescence in cell-free extract, upon transfecting HEK293T cells with pAcBac3-EcTyrTGA-EGFP** and pAcBac1-PylTAG (Fig. S5†), in the presence or absence of the two ncAAs. (C) Fluorescence microscopy images of the cells for the same experiment. (D) ESI-MS of the IMAC-purified protein confirms a mass consistent with the incorporation of the desired ncAAs.

Table 1. Representative yields of EGFP-39-TAG-151-TGA reporter incorporating various combinations of ncAAs.

| ncAA at 39TAG | ncAA at 151TGA | Yield (μg/10 cm dish) | Yield (% of wild-type reporter) |

| Tyr (wild type) | Tyr (wild type) | 175 | |

| BocK, 6 | OMeY, 1 | 13 | 7.5 |

| hPrK, 8 | AzF, 2 | 2 | 1.1 |

| PrY, 3 | AzK, 7 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| AzK, 7 | AcF, 4 | 1.8 | 1 |

| CpK, 9 | AzF, 2 | 8 | 4.6 |

| Cap, 5 | BocK, 6 | 4.5 | 2.6 |

Dual suppression using EcLeu and Pyl pairs

Our work identifies the combination of EcLeu + Pyl as an additional unexplored option for co-incorporating two distinct ncAAs into proteins in mammalian cells. To investigate the feasibility of using this new dual suppression system, we used a combination of EcLeuTAG + PylTGA, since the EcLeu pair does not suppress TGA efficiently. A pAcBac plasmid was constructed harboring a CMV-driven EcLeuRS, 8 copies of the tRNAEcLeuCUA driven by H1 promoters, and an EGFP-Y39TAG-Y151TGA reporter (Fig. S5C†). This plasmid was cotransfected with the aforementioned pAcBac plasmid harboring the PylTGA system, and the expression of the full-length EGFP reporter was monitored. Only when Cap and BocK were added at 1 mM concentration each did we observe robust expression of the EGFP reporter (Fig. 5B and S7†). ESI-MS analysis of the reporter protein isolated using IMAC confirmed successful incorporation of the two supplemented ncAA (Fig. 5C). Expression yield of EGFP-39TAG-151TGA reporter was found to be roughly 2.6% relative to the corresponding wild-type EGFP reporter (Table 1). So far, a very limited set of ncAAs have been genetically encoded in mammalian cells using the EcLeu system. However, this pair has been engineered to accept a set of structurally disparate ncAAs in S. cerevisiae,13,18,25–29 indicating the high plasticity of its active site. Further evolution of this aaRS/tRNA pair and the adaptation of the resulting systems in mammalian cells will facilitate the co-incorporation of many novel combinations of ncAAs.

Fig. 5. Site-specific incorporation of two ncAAs into EGFP-39-TAG-151-TGA using EcLeuTAG + PylTGA dual suppression system. (A) Scheme of the dual suppression. (B) Expression of the full length EGFP reporter, measured by its characteristic fluorescence in cell-free extract, upon transfecting HEK293T cells with pAcBac3-EcLeuTAG-EGFP** and pAcBac1-PylTGA (Fig. S5†), in the presence or absence of the two ncAAs. (C) ESI-MS of the IMAC-purified protein confirms a mass consistent with the incorporation of the desired ncAAs.

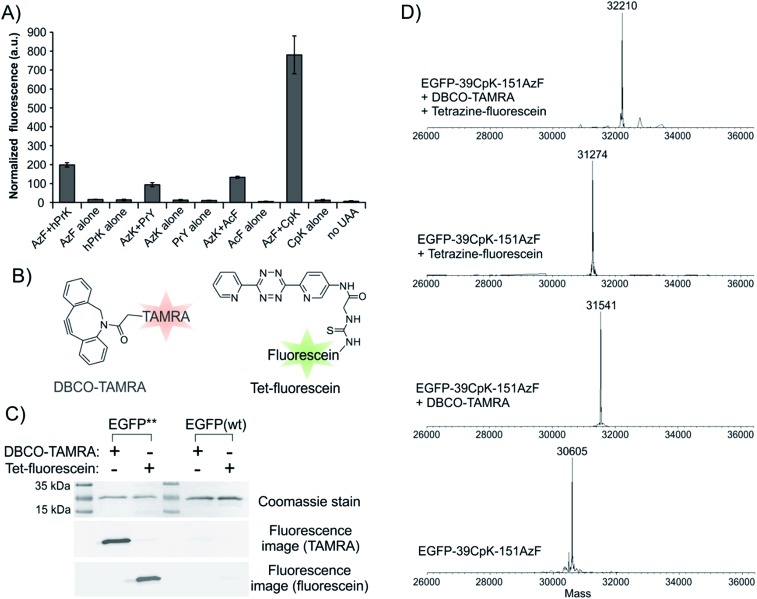

Site-specific incorporation of two mutually compatible bioconjugation handles

The ability to express proteins with two different functionalities for mutually compatible bioorthogonal conjugation chemistry is highly desirable, as it enables site-specific attachment of two distinct entities – such as two biophysical probes. Although two mutually compatible bioorthogonal handles (ketone and azide) were previously incorporated into two different subunits of one protein,15 the feasibility of incorporating two such ncAAs into a single polypeptide expressed in mammalian cells has not yet been demonstrated. Moreover, labeling the ketone side chain with alkoxyamines requires a low pH of 4.5, which significantly compromises the utility of this conjugation strategy. Being able to incorporate two functionalities, which can be independently and efficiently functionalized under physiologically relevant conditions would be more desirable. The Pyl pair has been engineered to genetically encode a large number of ncAAs with a diverse bioorthogonal conjugation handles.2,14,30–32 In contrast, a much more limited set is available through EcTyr (only 2, 3, and 4; Fig. 2),2,17 while no bioconjugation handle has been genetically encoded using EcLeu. In the experiment described in Fig. 4, both aaRSs are capable of charging several different ncAAs (i.e., polyspecific)2,3,14,17 with various bioconjugation handles. We took advantage of this polyspecificity to achieve simultaneous incorporation of (i) AzF (2; Fig. 2) + hPrK (8), (ii) PrY (3) + AzK (7), and (iii) AcF (4) + AzK, (iv) AzF + CpK (9), in each case incorporating different combinations of two distinct bioorthogonal conjugation handles into the reporter protein at the same time (Fig. 6A and S8†). Resulting full-length reporter proteins were purified by IMAC using a C-terminal poly-histidine tag (isolated yields of 1–8 μg/10 cm dish, 0.6–4.6% relative to wild-type EGFP; Table 1) and the incorporation of the appropriate ncAAs were verified by ESI-MS analysis (Fig. S9† and 6D). The azide, alkyne, ketone, and the cyclopropene functionalities incorporated using these amino acids can be functionalized using strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition,33 Cu(i)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition,34 condensation with hydrazine/alkoxyamines,35 and inverse electron demand Diels–Alder reaction with electron deficient tetrazines,36–38 respectively. The combination of azide and cyclopropene functionalities is particularly attractive, since the conjugation reactions used to label them spontaneously proceed under physiological catalyst-free conditions. Moreover, incorporation efficiency of AzF + CpK was found to be significantly higher relative to other combinations of bioconjugation handles (Fig. 6A and Table 1). Additionally, the bioconjugation reactions targeting these two groups should be mutually compatible enabling site-specific dual labeling of the resulting protein. Indeed, we demonstrated that the azide and the cyclopropene functionalities of EGFP-39CpK-151AzF can be fully labeled by DBCO-TAMRA and tetrazine-fluorescein, respectively, using SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS analysis (Fig. 6C and D). The labeling reactions could be performed simply by sequential addition of the two reagents in one pot under ambient conditions at pH 7. We also confirmed the presence of the azide and alkyne functionalities on EGFP-39hPrK-151AzF and EGFP-39PrY-151AzK by demonstrating their successful labeling using DBCO-Cy5 and Alexa Fluor488-picolyl azide, via strain-promoted33 and Cu(i)-catalyzed34 cycloaddition, respectively (Fig. S10†). Our work provides several options for site-specifically incorporating two bioconjugation handles into one protein expressed in mammalian cells, including one that enables spontaneous one-pot site-specific dual labeling of the resulting protein.

Fig. 6. Site-specific incorporation of two different bioconjugation handles into EGFP-39-TAG-151-TGA. (A) Expression of the full length EGFP reporter, measured by its characteristic fluorescence in cell-free extract, upon transfecting HEK293T cells with pAcBac3-EcTyrTGA-EGFP** and pAcBac1-PylTAG (for hPrK + AzF, AzK + AcF, and CpK + AzF), or pAcBac3-EcTyrTAG-EGFP** and pAcBac1-PylTGA (for AzK + PrY) in the presence or absence of indicated ncAAs. (B) Structures of DBCO-TAMRA and Tet-fluorescein. (C) Treating EGFP-39CpK-151AzF with DBCO-TAMRA or Tet-fluorescein leads to appropriate fluorescence-labeling, as shown by fluorescence imaging following SDS-PAGE. Wild-type EGFP fails to undergo labeling under identical conditions. (D) ESI-MS analysis reveals complete single or dual labeling of EGFP-39CpK-151AzF upon treatment with DBCO-TAMRA or Tet-fluorescein or both reagents.

Discussion

In this report we systematically explore the current scope and limitations of site-specifically incorporating two distinct ncAAs into proteins expressed in mammalian cells using the three available orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs. Our work highlights the importance of carefully characterizing potential cross-reactivities when combining two distinct aaRS/tRNA pairs for dual suppression. We found two significant cross-reactivities that limit the current scope of this technology: mischarging of the tRNAEcLeuCUA by EcTyrRS, and the undesired suppression of the TAG codon by TAA-suppressor tRNAs in general. Although it is likely that a TAG-suppressor tRNA would significantly outcompete its TAA-suppressing counterpart for charging the TAG codon when both are present, low levels of ncAA-misincorporation at this site will be sufficient to jeopardize many downstream applications. This could be further exacerbated if the engineered aaRS charging the TAG suppressor tRNA has a lower activity than the one charging the TAA suppressor. Consequently, the use of the TAG + TAA codon combination for dual suppression is not optimal. It is possible that the observed cross-reactivity between TAG-suppressing tRNAEcLeuCUA and EcTyrRS may be avoided if a different anticodon variant of tRNAEcLeu could be used.20 However, the utility of the other nonsense suppressors of tRNAEcLeu is compromised by their very low suppression efficiency. It may be possible to engineer tRNAEcLeu in the future to eliminate its unexpected cross-reactivity with EcTyrRS, and facilitate the development of a 3rd dual suppression system in mammalian cells using EcLeu and EcTyr.

We have also developed two unique platforms for dual-ncAA mutagenesis in mammalian cells by generating plasmid systems that co-express EcTyrTGA + PylTAG or EcLeuTAG + PylTGA suppressors. The utility of the former system was highlighted by site-specifically incorporating an azide and an alkyne, a ketone and an azide, and a cyclopropene and an azide into proteins expressed in mammalian cells. Spontaneous one-pot quantitative functionalization of both bioorthogonal groups in the CpK + AzF dual-labeled protein was also demonstrated, simply by sequentially adding the cyclooctyne and the tetrazine reagents to the protein. Several additional combinations of mutually compatible bioorthogonal conjugation chemistries have recently been developed that enables facile, spontaneous dual modification of target proteins.10,39–41 Further development of our dual-ncAA mutagenesis platforms to access these chemistries which can be independently functionalized in the context of a living cell will provide powerful technology to probe and engineer protein function in vivo.

Despite these exciting advances, low efficiency of dual nonsense suppression (0.6–7.5% of wild-type reporter) currently limits the overall scope of this technology. One major factor contributing to the low efficiency is the weak activity of the TGA suppressor tRNAs relative to their TAG-suppressing counterparts. Using directed evolution to develop more efficient TGA suppressing tRNAs may circumvent this issue. Another factor that restricts the current scope of dual ncAA mutagenesis arises from the limited set of ncAAs that have been genetically encoded in eukaryotes using the EcTyr or the EcLeu pairs, relative to Pyl. Since Pyl is orthogonal both in eukaryotes and bacteria, it is the only eukaryote-compatible platform which can be engineered using the facile E. coli selection system to change its substrate specificity.1–3,20 Consequently, the overwhelming majority of the ncAAs have been genetically encoded in eukaryotes using this platform.2,20 Development of additional platforms which can be engineered using the E. coli selection system to generate ncAA-specific variants can overcome this limitation.20 A third challenge comes from the suboptimal efficiency of the mutant aaRSs for charging some of the ncAAs of interest. For example, the efficiency of simultaneously incorporating OMeY and BocK (Fig. S6† and Table 1) was significantly higher than other ncAA combinations, when using the same expression system. Further evolution of the aaRSs to achieve improved charging of the desirable ncAAs could also enhance the efficiency of dual ncAA incorporation.

Conclusions

Site-specific dual ncAA mutagenesis is an emerging technology with enormous potential. Our work takes a systematic approach to define the current scope of this technology in mammalian cells, and establishes two distinct platforms for incorporating two different ncAAs into proteins expressed in these cells. We also highlight the need to further expand the repertoire of ncAAs genetically encoded in eukaryotes using the EcTyr and EcLeu pairs, and to develop improved TGA suppressor tRNAs for this technology to realize its full potential and spur a plethora of powerful applications.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank NIH (R01GM124319 to A. C.) and The Richard and Susan Smith Family Foundation, Newton, MA, for financial support.

Footnotes

References

- Chin J. W. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014;83:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas A., Lercher L., Spicer C. D., Davis B. G. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:50–69. doi: 10.1039/c4sc01534g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. C., Schultz P. G. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Brock A., Chen S., Chen S., Schultz P. G. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Takimoto J. K., Louie G. V., Baiga T. J., Noel J. P., Lee K. F., Slesinger P. A., Wang L. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1063–1072. doi: 10.1038/nn1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K., Hayashi A., Sakamoto A., Kiga D., Nakayama H., Soma A., Kobayashi T., Kitabatake M., Takio K., Saito K., Shirouzu M., Hirao I., Yokoyama S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4692–4699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney C. M., Wissner R. F., Petersson E. J. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015;28:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Sun S. B., Furman J. L., Xiao H., Schultz P. G. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1828–1837. doi: 10.1021/bi4000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W., Huang Y., Wang Z., Russell W. K., Pai P. J., Russell D. H., Liu W. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:3211–3214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Sachdeva A., Cox D. J., Wilf N. M., Lang K., Wallace S., Mehl R. A., Chin J. W. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H., Wang K., Davis L., Garcia-Alai M., Chin J. W. Nature. 2010;464:441–444. doi: 10.1038/nature08817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J. W., Cropp T. A., Anderson J. C., Mukherji M., Zhang Z., Schultz P. G. Science. 2003;301:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.1084772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N., Deiters A., Cropp T. A., King D., Schultz P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14306–14307. doi: 10.1021/ja040175z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W., Tharp J. M., Liu W. R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1844:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Chatterjee A., Choi S. H., Bajjuri K. M., Sinha S. C., Schultz P. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:14080–14083. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W., Schultz P. G., Guo J. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:1640–1645. doi: 10.1021/cb4001662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Xiao H., Bollong M., Ai H. W., Schultz P. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:11803–11808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309584110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustad E., Bushey M. L., Brock A., Chittuluru J., Schultz P. G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:6004–6006. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani G., McClain W. H. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:18–23. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italia J. S., Addy P. S., Wrobel C. J., Crawford L. A., Lajoie M. J., Zheng Y., Chatterjee A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. J., Adachi T., Inokuchi H., Soll D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:3463–3467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll L., Berg P. Nature. 1969;223:1340–1342. doi: 10.1038/2231340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Lewis Jr T. L., Igo P., Polleux F., Chatterjee A. ACS Synth. Biol. 2017;6:13–18. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied W. H., Elsasser S. J., Uttamapinant C., Chin J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15577–15583. doi: 10.1021/ja5069728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai H. W., Shen W., Brustad E., Schultz P. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:935–937. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerer D., Chen S., Wu N., Deiters A., Chin J. W., Schultz P. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:9785–9789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Guo J., Lee H. S., Schultz P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12540–12543. doi: 10.1021/ja4059553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. S., Guo J., Lemke E. A., Dimla R. D., Schultz P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12921–12923. doi: 10.1021/ja904896s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke E. A., Summerer D., Geierstanger B. H., Brittain S. M., Schultz P. G. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Z., Hong S., Chen X., Chen P. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:742–751. doi: 10.1021/ar200067r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikić I., Kang J. H., Girona G. E., Aramburu I. V., Lemke E. A. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:780–791. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K., Chin J. W. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4764–4806. doi: 10.1021/cr400355w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletten E. M., Bertozzi C. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:666–676. doi: 10.1021/ar200148z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldal M., Tornøe C. W. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952–3015. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen A., Dawson P. E. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:2543–2548. doi: 10.1021/bc800310p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman M. L., Royzen M., Fox J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13518–13519. doi: 10.1021/ja8053805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj N. K., Weissleder R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:816–827. doi: 10.1021/ar200037t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K., Chin J. W. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:16–20. doi: 10.1021/cb4009292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva A., Wang K., Elliott T., Chin J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7785–7788. doi: 10.1021/ja4129789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikic I., Plass T., Schraidt O., Szymanski J., Briggs J. A., Schultz C., Lemke E. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:2245–2249. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. M., Prescher J. A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015;28:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.