Abstract

The first total synthesis of aspeverin, a prenylated indole alkaloid isolated from Aspergillus versicolor in 2013, is described. Key steps utilized to assemble the core structure of the target include a highly diastereoselective Diels-Alder reaction, a Curtius rearrangement, and a unique strategy for installation of the geminal dimethyl group. A novel iodine(III)-initiated cyclization was then used to install the bicyclic urethane linkage distinctive to the natural product.

Graphical abstract

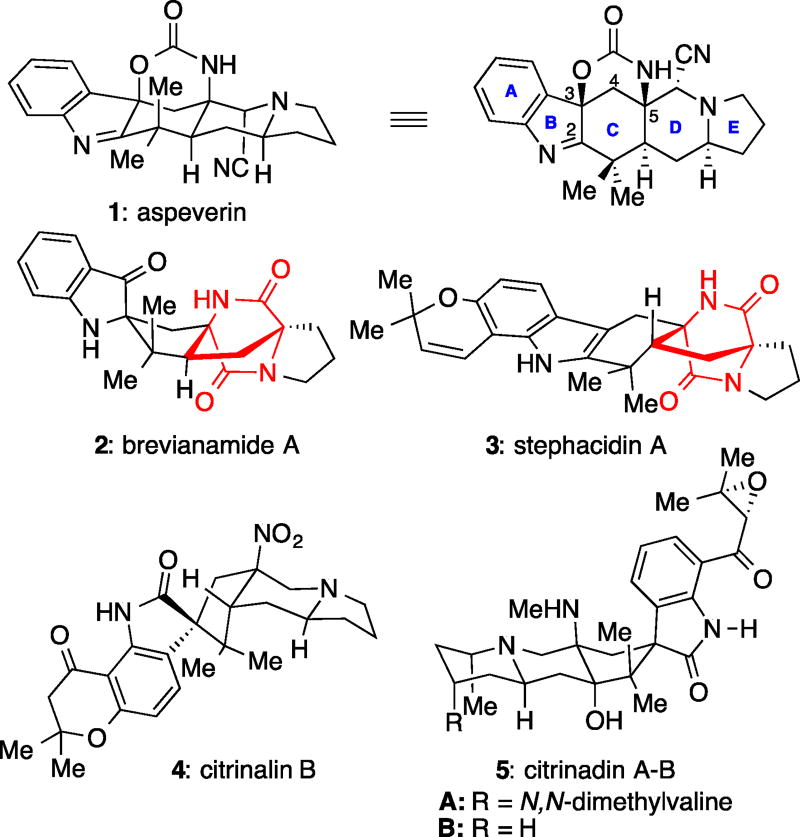

Prenylated indole alkaloids derived from fungi constitute a broad class of secondary metabolites containing a diverse array of molecular structures. Many of these alkaloids display important biological activities ranging from antibiotic and antihelmintic properties to potent cytotoxicity.1 This diversity in both structure and function has rendered various prenylated indoles attractive targets in total synthesis studies.2 Reported by Ji and co-workers and isolated from Aspergillus versicolor, aspeverin (1) has a number of structural features that prompted our attention from a synthetic perspective (Figure 1). Most striking is the unprecedented cyclic urethane linkage, joining the angular nitrogen atom in the C:D ring junction and the C-3 carbon of the indole ring. Additionally, 1 contains a rarely observed α-cyanoamine linkage.3

Figure 1.

Representative Prenylated Indole Alkaloids and Structure of Aspeverin (1).

A number of prenylated indole alkaloids with unusual scaffolds, including citrinalin B (4) and citrinadins A–B (5) among others, have received much synthetic attention in recent years.4,5 It is hypothesized that these molecules are biosynthetically derived from indole alkaloids bearing a bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane core structure, highlighted in red in the cases of 2 and 3.4b,1b The total syntheses of citrinadins A and B (5) were completed in 2013 by the Martin and Wood groups, respectively.6,7 During the course of our studies, elegant syntheses of ent-citrinalin B (ent-4) and cyclopiamine B (not shown) and related biosynthetic studies were completed in a collaborative venture between the Sarpong, Berlinck, Miller, Tantillo, and Andersen groups.8 Aspeverin appears to share structural similarities with this growing group of natural products, and it may well share similar origins.

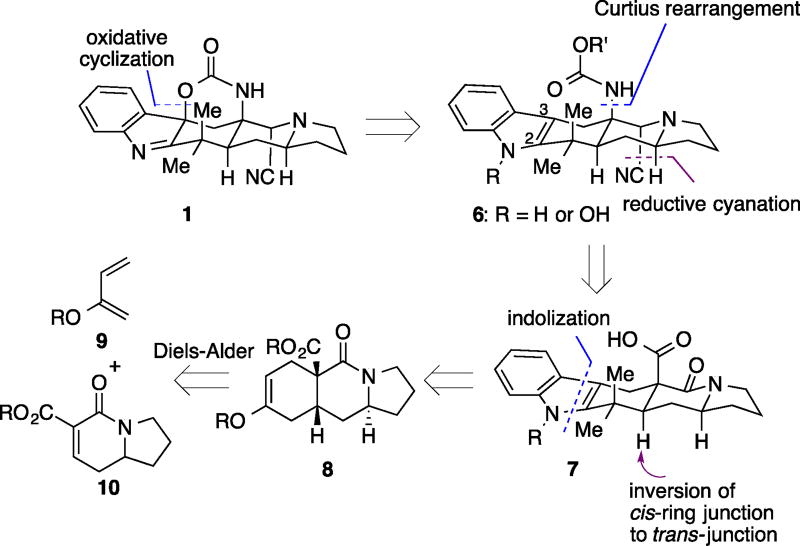

Retrosynthetically, we envisioned the synthesis of 1 as occurring through a late-stage oxidative cyclization of 6 to install the bicyclic urethane linkage. In this fashion, the normally nucleophilic indole would be serving as the electrophilic component in the cyclization event (Figure 2). Although oxidatively mediated addition of carbamates to 2,3-dialkyl substituted indoles has not been previously explored, we hoped that suitable electrophilic activation of the indole would set the stage for cyclization of a pendant carbamate.9 Indeed, oxidatively initiated addition of other nucleophiles to the C-3 carbon of indoles mediated by hypervalent iodine reagents as well as other oxidants are known.10,11 Alternatively, the corresponding N-hydroxyindole might also serve to enable nucleophilic attack of a carbamate at the C-3 position of the indole.11b, 12 We anticipated that our proposed route could well be preferable to an alternate approach involving discrete oxidation of the indole to a 3-hydroxyindolenine. Thus, in our proposed route, there is no need to control the stereochemical relationship between C3 and C5 (as shown in Figure 1). Moreover, 3-hydroxyindolenines are prone to undergo rearrangements to yield either pseudoindoxyl or spiro-oxindole rings.13 An oxidative cyclization approach would circumvent both of these potential issues.

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic Analysis

The α-cyanoamine functionality in 6 was traced back via a reductive cyanation of the corresponding lactam, culminating in axial attack of cyanide onto an intermediate iminium ion to control diastereoselectivity.14 The angular nitrogen atom could, in turn, arise from a Curtius-type rearrangement, thus leading back to carboxylic acid 7. This disconnection then prompted the possibility of using the ester precursor of the acid as a dienophilic activating group to build the CDE ring system of the molecule via a Diels-Alder reaction between 9 and 10, with facial selectivity guided by the distal stereocenter in indolizidine 10.15

This route would require manipulation of Diels-Alder adduct 8 to convert the initial cis-ring fusion into the required trans junction found in the natural product. We anticipated two potential synthetic sequences toward this end (Figure 3). It was previously shown that enol ethers within cis-decalin ring systems can undergo olefin isomerization, an effect we have capitalized upon to synthesize “iso-Robinson annulation” products such as 11.16 We were also interested in using known indole reactivity to form the trans-ring junction through a benzylic oxidation of indole 12.17 Thus a ketone (cf 13) would be used to achieve epimerization (cf 14). The ketone would then serve as a functional handle for installation of the geminal dimethyl group.

Figure 3.

Alternate Strategies for Conversion of 8 to 7

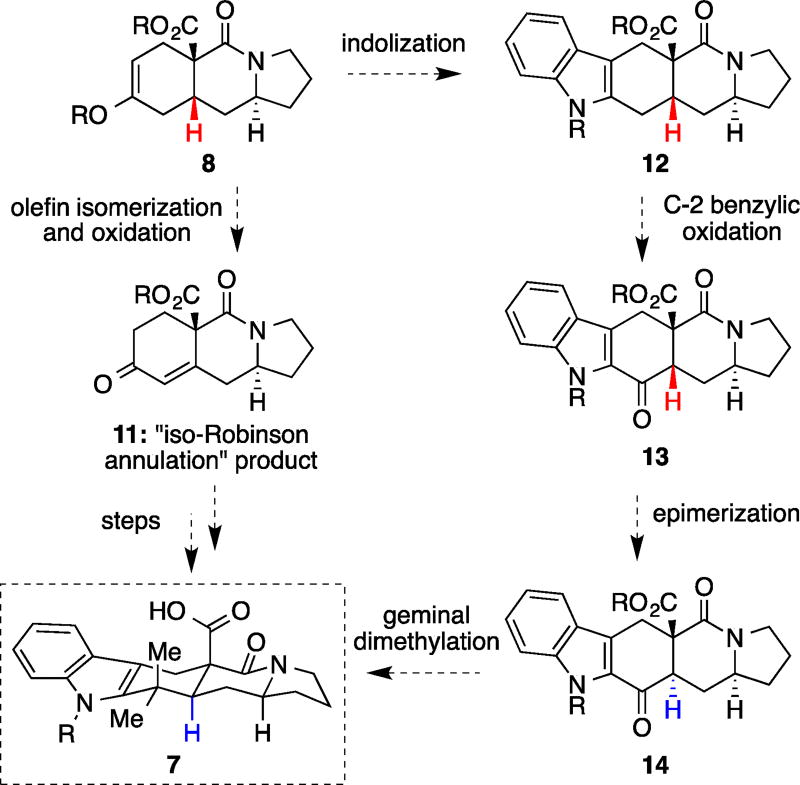

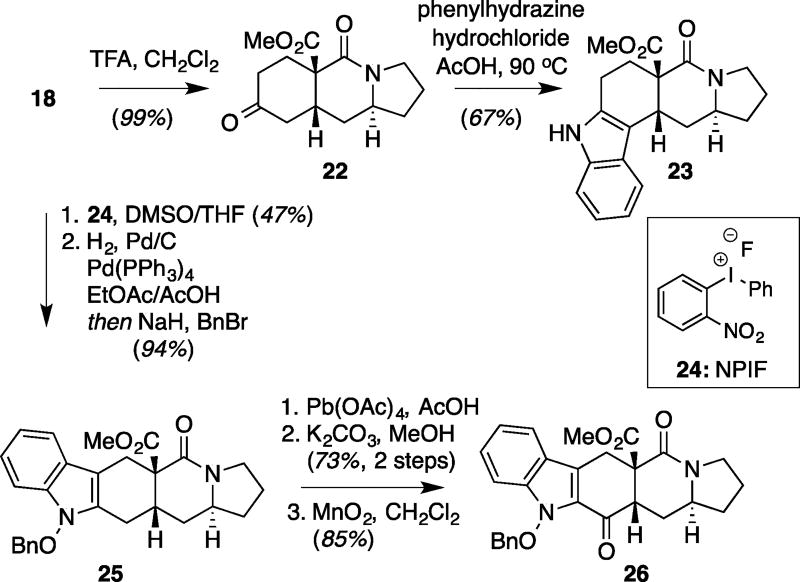

In the forward direction, we started with known indolizidine 15 (Scheme 1).18 Iodination of 15 using modified conditions reported by Johnson and co-workers, followed by a Pd-catalyzed carbonylation of the resulting iodide gave 16.19 As expected, 16 smoothly underwent a Diels-Alder reaction with 17 in the presence of ZnCl2 at room temperature to furnish 18 as a single diastereomer in 91% yield. We then explored both strategies discussed above to access key intermediate 21. Indeed, we found that the silyl enol ether double bond of 18 could be isomerized under previously described conditions to furnish 19.16a Subsequent oxidation of 19 via formation of the corresponding phenylselenide followed by elimination of the in-situ generated selenoxide furnished enone 20. It is well to note that this intermediate contains the stereochemical configuration opposite to that expected to arise using a Robinson annulation strategy.20 Unfortunately, preliminary efforts to efficiently elaborate enone 20 (and related systems) to furnish the trans-ring junction with the requisite geminal dimethyl group in place were not successful. Ultimately, we pursued the second strategy discussed in Figure 3.

Scheme 1.

Diels-Alder Reaction and Olefin Isomerization-Oxidation Sequence.

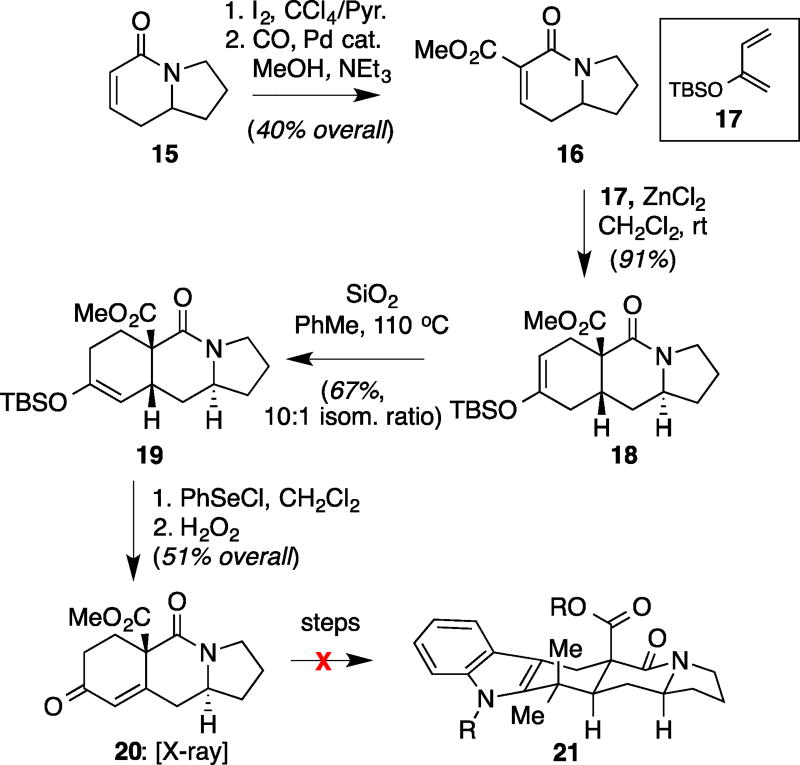

In this approach, we hoped to install the indole ring prior to inversion of the C:D ring junction and use the inherent reactivity of indoles to functionalize at the C-2 benzylic position. Reaction of 22 with phenylhydrazine produced only the undesired Fischer indole regioisomer 23. This regioselectivity was not unexpected, given the established regiochemical preference for Fischer indole syntheses within cis-fused ring systems.21 Accordingly, a two-step approach was taken. Regioselective arylation of 18 with o-nitrophenyliodonium fluoride (NPIF) 24 furnished a nitroaryl ketone, which underwent reductive cyclization, as precedented, to afford benzylated N-hydroxyindole 25 in excellent yield.22,23

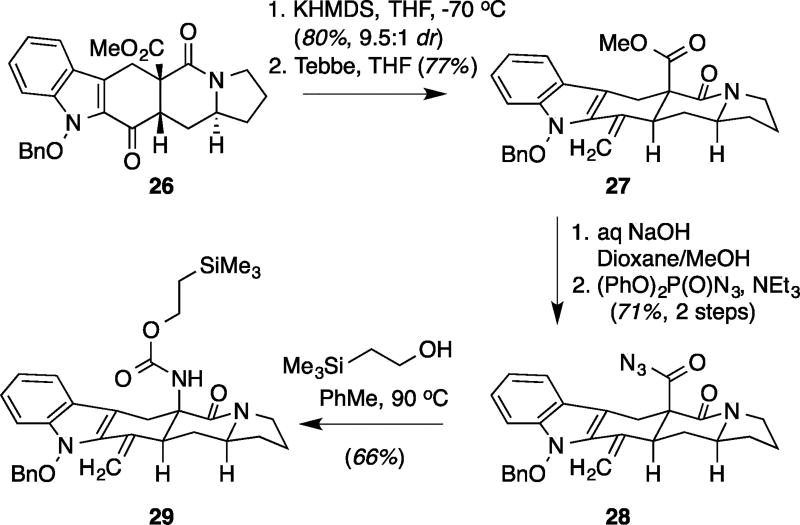

With the pentacylic ring system in place, we focused our attention towards inverting the cis-ring fusion. Using a stepwise oxidation approach, 25 efficiently reacted with Pb(OAc)4 in AcOH to install an acetate functionality benzylic to the C-2 carbon of the indole.17c Subsequent hydrolysis and oxidation of the resulting alcohol using MnO2 afforded the desired ketone 26 in good overall yield. Pleasingly, following treatment with KHMDS at low temperature, the enolate of 26 underwent kinetic protonation to yield the desired trans-ring junction in 9.5:1 dr (separable) and 80% isolated yield (Scheme 3). Although attempts at functionalizing this electron-rich ketone proved to be quite challenging, methylenation could be accomplished using the Tebbe reagent, giving 27 in 77% yield.24 Before turning our attention to installation of the requisite geminal dimethyl group, we first subjected the carboxylic acid of 27 to Curtius rearrangement conditions.25 Formation of acyl azide 28 followed by thermolysis in the presence of 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethanol yielded the desired carbamate 29.

Scheme 3.

Epimerization and Curtius Rearrangement.

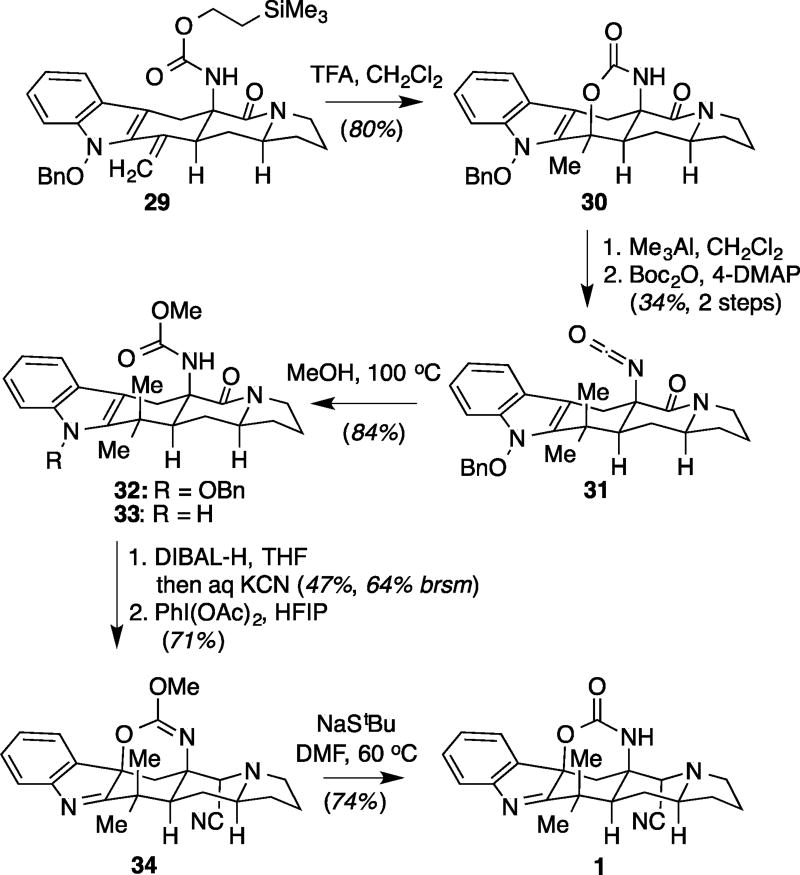

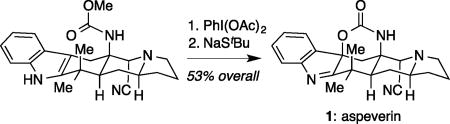

Faced with the challenge of converting the exocyclic methylene into a geminal dimethyl group, an unexpected cyclization product ultimately proved to be useful. Treatment of 29 with TFA cleanly afforded bicycle 30 in 80% yield (Scheme 4). Reaction of 30 with Me3Al successfully reopened the cyclic carbamate to install the desired geminal dimethyl group, with formation of the corresponding primary amine. Attempts to reprotect the free amine with a tert-butoxycarbonyl group instead resulted in formation of stable isocyanate 31 in 34% yield over two steps.26 Upon heating 31 in MeOH, 32 is rapidly formed (not isolated). Extended heating of 32, however, led entirely to 33 (and benzaldehyde) via disproportionation of the N-benzyloxy indole. Partial reduction of 33 with DIBAL-H followed by workup with a concentrated KCN solution afforded the corresponding α cyanoamine as a single diastereomer in 47% yield along with recovered starting material.27 Gratifyingly, upon treatment with a slight excess of PhI(OAc)2 in HFIP, this carbamate underwent the desired oxidative cyclization to form 34 in 71% yield as the only substantially observed product. Subsequent demethylation using sodium tert-butylthiolate in DMF cleanly afforded 1 in 74% yield, which was in spectroscopic agreement with reported data for the natural product.

Scheme 4.

Completion of the Synthesis of Aspeverin.

In summary, we have completed the first total synthesis of aspeverin (1) in 20 steps from known indolizidine 15. Moreover, 15 is known in enantiopure form, lending this synthetic route to an asymmetric synthesis if desired.18,28 Key steps in our overall route include: (1) a highly diastereoselective Diels-Alder reaction to build up the CDE ring system of the molecule, which can be efficiently epimerized to yield the desired trans-ring fusion; (2) an unconventional approach to the installation of a geminal dimethyl group via a Me3Al-mediated ring opening of 30; and (3) a novel oxidative cyclization of an angular carbamate promoted by PhI(OAc)2 to yield the cyclic urethane linkage observed in the natural product. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first example of an intramolecular cyclization of a carbamate functionality onto an indole mediated by a hypervalent iodine reagent, a strategy that may have further implications for substrate-controlled oxidations of indoles.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Attempted Fischer Indole Synthesis and Regioselective Indolization Followed by Benzylic Oxidation.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Samuel J. Danishefsky (MSKCC) is foremost acknowledged for his intellectual mentorship and for his assistance in preparation of this manuscript. Support was provided by an Amgen predoctoral fellowship as well as the Tri-Institutional PhD Program in Chemical Biology (MSKCC, Weill-Cornell Medical College, Rockefeller University). We thank Dr. George Sukenick (MSKCC) for NMR assistance and the MSKCC core facility for mass spectrometric assistance; Serge Ruccolo (Columbia University, Gerard Parkin Lab) for X-ray experiments (NSF, CHE-0619638); and Drs. Andrew G. Roberts and William F. Berkowitz (MSKCC) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental procedures, characterization data (including spectra for new compounds), X-ray crystal structures, and CIF data can be found in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Williams RM, Stocking EM, Sanz-Cervera JF. Top. Curr. Chem. 2000;209:97–173. [Google Scholar]; (b) Finefield JM, Frisvad JC, Sherman DH, Williams RM. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:812–833. doi: 10.1021/np200954v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Miller KA, Williams RM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3160–3174. doi: 10.1039/b816705m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For representative examples: Williams RM, Glinka T, Kwast E, Coffman H, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:808–821.von Nussbaum F, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:2259–2262. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000616)39:12<2175::aid-anie2175>3.0.co;2-j.Schkeryantz JM, Woo JCG, Siliphaivanh P, Depew KM, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11964–11975.Baran PS, Guerrero CA, Hafensteiner BD, Ambhaikar NB. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:3960–3963. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461864.Herzon SB, Myers AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5342–5344. doi: 10.1021/ja0510616.Williams RM, Cao J, Tsujishima H, Cox RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12172–12178. doi: 10.1021/ja036713+.

- 3.Ji N-Y, Liu X–H, Miao F-P, Qiao M-F. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2327–2329. doi: 10.1021/ol4009624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Tsuda M, Kasai Y, Komatsu K, Sone T, Tanaka M, Mikami Y, Kobayashi J. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3087–3089. doi: 10.1021/ol048900y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mugishima T, Tsuda M, Kasai Y, Ishiyama H, Fukushi E, Kawabata J, Watanabe M, Akao K, Kobayashi J. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:9430–9435. doi: 10.1021/jo051499o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kushida N, Watanabe N, Okuda T, Yokoyama F, Gyobu Y, Yaguchi T. J. Antibiotics. 2007;60:667–673. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pimenta EF, Vita-Marques AM, Tininis A, Seleghim MHR, Sette LD, Veloso K, Ferreira AG, Williams DE, Patrick BO, Dalisay DS, Andersen RJ, Berlinck RGS. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1821–1832. doi: 10.1021/np100470h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bian Z, Marvin CC, Martin SF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10886–10889. doi: 10.1021/ja405547f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong K, Enquist JA, Jr, McCallum ME, Smith GM, Matsumaru T, Menhaji-Klotz E, Wood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10890–10893. doi: 10.1021/ja405548b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercado-Marin EV, Garcia-Reynaga P, Romminger S, Pimenta EF, Romney DK, Lodewyk MW, Williams DE, Andersen RJ, Miller SJ, Tantillo DJ, Berlinck RGS, Sarpong R. Nature. 2014;509:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature13273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Although not directly applicable in this context, intramolecular cyclizations of carbamates onto 2-thiophenyl substituted indoles have been reported: Feldman KS, Vidulova DB, Karatjas AG. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6429–6440. doi: 10.1021/jo050896w.

- 10.For examples of hypervalent iodine-mediated addition of nucleophiles to indoles: Awang DVC, Vincent A. Can. J. Chem. 1980;58:1589–1591.Braun NA, Bray JD, Ciufolini MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4985–4988.Takayama H, Misawa K, Okada N, Ishikawa H, Kitajima M, Hatori Y, Murayama T, Wongseripipatana S, Tashima K, Matsumoto K, Horie S. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5705–5708. doi: 10.1021/ol062173k.Ishikawa H, Takayama H, Aimi N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5637–3639.

- 11.(a) Newhouse T, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10886–10887. doi: 10.1021/ja8042307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gassman PG, Campbell A, Mehta G. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:2749–2758. [Google Scholar]; (c) Büchi G, DeShong PR, Katsumura S, Sugimura Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:5084–5086. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somei M, Noguchi K, Yamada F. Heterocycles. 2001;55:1237–1240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Greshock TJ, Grubbs AW, Williams RM. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6124–6130. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miller KA, Tsukamoto S, Williams RM. Nature Chem. 2009;1:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nchem.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Finch N, Gemenden CW, Hsu IH–C, Kerr A, Sim GA, Taylor WI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:2229–2235. doi: 10.1021/ja01088a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polniaszek RP, Belmont SE. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4868–4874. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brewster AG, Broady S, Glenn E, Hermitage SA, Hughes M, Moloney MG, Woods G. Lett. in Org. Chem. 2005;2:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng F, Dai M, Angeles AR, Danishefsky SJ. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:3076–3080. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20868G.Angeles AR, Dorn DC, Kou CA, Moore MAS, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1451–1454. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604308.Angeles AR, Waters SP, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13765–13770. doi: 10.1021/ja8048207.For a detailed analysis of olefin stability in fused ring systems: Velluz L, Valls J, Nominé G. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 1965;4:181–270.

- 17.For representative examples of oxidation benzylic to the C-2 position of indoles: Yoshida K, Goto J, Ban Y. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1987;35:4700–4704.Zaimoku H, Hatta T, Taniguchi T, Ishibashi H. Org. Lett. 2012;14:6088–6091. doi: 10.1021/ol302983t.Kametani T, Takahashi K, Kigawa Y, Ihara M, Fukumoto K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1977:28–31.Sakai S–I, Kubo A, Katsuura K, Mochinaga K, Ezaki M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1972;20:76–81.

- 18.Park SH, Kang HJ, Ko S, Park S, Chang S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:2621–2624. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CR, Adams JP, Braun MP, Senanayake CBW, Wovkulich PM, Uskokovic MR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:917–918. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) House HO, Umen MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1000–1003. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wenkert E, Berges DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:2507–2509. doi: 10.1021/ja00986a061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Howe R, McQuillin FJ. J. Chem. Soc. 1955:2423–2428. [Google Scholar]

- 21.For a detailed analysis of the regioselectivity of Fischer indole syntheses within fused ring systems of varying stereochemistry: Diedrich CL, Frey W, Christoffers J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007;28:4731–4737.

- 22.(a) Iwama T, Birman VB, Kozmin SA, Rawal VH. Org. Lett. 1999;1:673–676. doi: 10.1021/ol990759j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kozmin SA, Rawal VH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:13523–13524. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belley M, Beaudoin D, St-Pierre G. Synlett. 2007:2999–3002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tebbe FN, Parshall GW, Reddy GS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:3611–3613. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiori T, Ninomiya K, Yamada SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:6203–6205. doi: 10.1021/ja00772a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knölker H–J, Braxmeier T, Schlechtingen G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:2497–2500. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durand J–O, Larchevêque M, Petit Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5743–5746. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alternatively, compound S2 (see Supporting Information) is known in enantioenriched form: Stead D, O’Brien P, Sanderson A. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1409–1412. doi: 10.1021/ol800109s.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.