Abstract

Background:

Obesity in adolescence is the strongest risk factor for obesity in adulthood. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention on different anthropometric indices in 12–16-year-old boy adolescents after 12 Weeks of Intervention.

Methods:

A total of 96 male adolescents from two schools participated in this study. The schools were randomly assigned to intervention (53 students) and control school (43 students). Height and weight of students were measured and their body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Body fat percent (BF) and body muscle percent (BM) was assessed using a bioimpedance analyzer considering the age, gender, and height of students at baseline and after intervention. The obesity reduction intervention was implemented in the intervention school based on the Ottawa charter for health promotion.

Results:

Twelve weeks of intervention decreased BF percent in the intervention group in comparison with the control group (decreased by 1.81% in the intervention group and increased by 0.39% in the control group, P < 0.01). However, weight, BMI, and BM did not change significantly.

Conclusions:

The result of this study showed that a comprehensive lifestyle intervention decreased the body fat percent in obese adolescents, although these changes was not reflected in the BMI. It is possible that BMI is not a good indicator in assessment of the success of obesity management intervention.

Keywords: Adolescence obesity, BMI, body composition, lifestyle intervention

Introduction

Obesity is an important risk factor for many chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and osteoarthritis.[1,2,3] Adolescence period is considered an important period of physical growth and many biological, behavioral, and environmental factors can influence weight and body composition.[4] The change of body composition itself influences the risk of the other diseases through changing the sensitivity to insulin and the accumulation of adipokines.[5] The percent of obese adolescents (12–19-year-old) from 1980 to 2012 has reached about 21%.[6] Obesity in childhood and adolescence period is the prerequirement for adulthood obesity, type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, resistance to insulin, and the increasing of inflammatory cytokines.[7,8]

Available methods for evaluating the obesity in children and adolescents include the measurement of weight, body mass index (BMI), the percent of body fat (BF) and body muscle (BM), skin fold, and some laboratories methods.[9] Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold standard for determining the body composition.[10] It is a credible and trusted method for evaluating body composition in adults and children. Although DXA is an expensive and immobile method and also causes the exposure of the bones with rays.[11,12,13] In a study aimed to identify a cheaper and simpler method rather than DXA for evaluating BF in obese and overweight adolescent, it was recommended that bioimpedance analyzer compared with DXA could be the simplest and most exact fat tissue state in obese adolescents.[14] On the other hand, BMI is considered as the most popular method for the assessment of weight status. The persons younger than 20 with percentile of 95 and higher in BMI standard curves for this age was considered to be obese.[11] However, the main purpose of weight loss intervention in children and adolescents is decreasing the fat mass (FM) and maintain BM well regardless of its effect on their weight.[15] Hence, the purpose of this study was the implementation of a comprehensive health promotion intervention and the evaluation of its effects on different anthropometric measurements in 12–15-year-old adolescent boys. Furthermore, the focus of this paper is to compare of two assessment methods of physical health and fitness in adolescents: BMI and body composition.

Methods

This study was a randomized, controlled, school-based trial and carried out as a comprehensive health promoting school program involving 96 students in two boys’ high schools (including the grades 7–9) of a randomly chosen district of Tehran city (the district 5). Two schools were randomly allocated as the intervention and control schools.

The selection criteria of the schools included enrolled students were 12–15-year-old, they were similar regarding the implementation of health and sanitary programs and far enough physical distance from each other to reduce the possibility of interaction of students of case and control school. Considering that both schools were chosen from the same district, it was expected that the students were similar in terms of socioeconomic class and ecological and social backgrounds.

After conducting required coordination with schools, identifying obese and overweight students and obtaining consent forms from students and parents, 96 obese and overweight students (52 students in intervention school and 46 students in control school) participated in this study and all of them completed the study. Inclusion criteria were (i) age = 12–15 years; (ii) BMI ≥2 Z-scores; and (iii) lack of disease affecting weight.

Anthropometric measures

The height of students was measured with a calibrated tapeline fastened to a wall. Omron-BF511 bioimpedance analyzer (this device is a digital, mobile, and nonaggressive device that have eight electrodes that transfers the weak electrical currents [50 kHz and lower than 500 μA] through hands and feet) was utilized to measure weight, BMI, BF, and BM. The validity of this device has been confirmed in previous studies.[16] All measures have been taken between morning and noon at the beginning and after 12 weeks of intervention.

Intervention

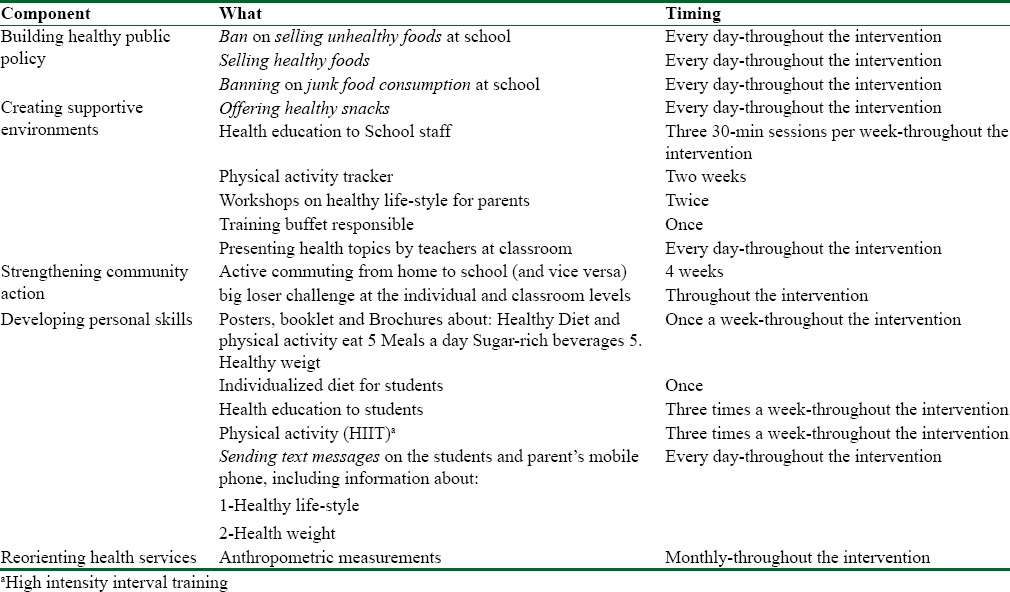

The intervention was implemented in school for 12 weeks (from February to May 2016) in two levels: in the first level, the environmental and lifestyle changes were applied to the school level, so all the students in the intervention school were covered. The five dimensions of Ottawa Charter[17] were used for systemic implementation of interventions in school level. Our intervention objects were (1) modify the health policy at the school level to influence weight and BMI, (2) creating supportive environment to weight reduction, (3) strengthen community action to achieve a healthy weight, (4) developing personal skills to adopt a healthy lifestyle, and (5) reorienting health services to prevent and treatment of obesity.[18] We had some strategies for every object and many operational activities for every strategy. The summary of our interventions is outlined in Table 1.[18]

Table 1.

Components of the intervention based on Ottawa charter dimensions

In the second level, the lifestyle interventions specifically covered obese students. At this level, the personalized diet and physical activity intervention were implemented for each participant. In addition, parents were provided an educational session regarding healthy meals and creating a supportive environment at home for healthy diet and physical activity. The method of appropriate implementation of diet has been instructed to parents and students through a face-to-face training, followed by booklets and phone calls. The personalized diet was adopted with free snacks offered in school days by researchers.

Furthermore, a high-intensity interval training[19] was carried out for improving the physical activity at the schools. In this method, students warmed up for 10 min under supervision of an exercise physiologist and they were involved in high-intensity exercise for a minimum of 30 min. At the end, they were given time to cool down their bodies. The details of exercise program have been explained elsewhere.[18] This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Reference Number: Ir.sbmu.nnftri.rec. 1394.22), Tehran, Iran.

Statistical analysis

Independent t-test was used to compare intervention and control groups at baseline. Furthermore, general linear model repeated measures was used to compare weight, height, BMI, and body composition changes of students in the intervention school with the control school's students considering both between groups and within (before and after in each group) groups differences together. Data were analyzed with SPSS for Windows version 7.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

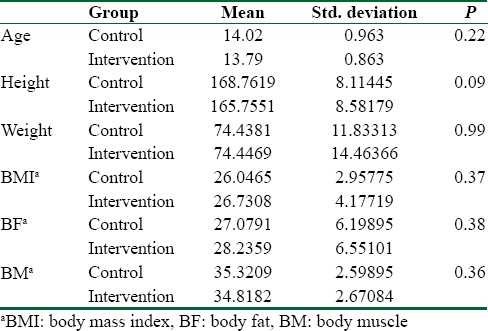

The study group included 96 adolescent boys with BMI ≥2 Z-scores for age and sex. The characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences between groups in age, height, weight, BMI, or BF before the intervention.

Table 2.

Comparison between characteristics of the subjects at baseline using independent t-test

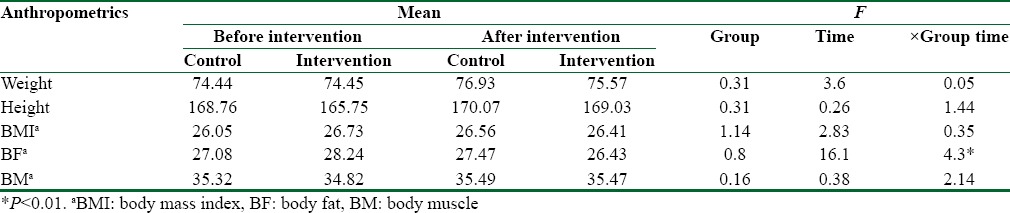

After 12 weeks of intervention, BF decreased significantly in intervention group's students in comparison with control group's students (decreased by 1.81% in intervention group and increased by 0.39% in control group, F = 4.3, P < 0.01). However, weight, BMI, and BM did not change significantly [Table 3].

Table 3.

Differences between anthropometric measurements of students using GLM repeated measures (df=1)

Discussion

This paper reports partly on effect of a comprehensive health promoting school program on different anthropometric measurements of 12–16-year-old boys. After 12 weeks of comprehensive intervention, a significant loss of FM has been observed, but there was no significant change in BMI level.

Regarding to the effects of lifestyle interventions on youth's body composition, the result of this study was compatible with some previous studies’ results.[4,20,21] In a study with 12-month intervention, lifestyle change and the use of Sibutramine in obese adolescents resulted in the increase of lean mass and decrease of FM.[20] In two other studies, the dietary-behavioral activity in 9-month[4] and 3-month[21] period in adolescents resulted in the reduction of fat tissue percent and maintain muscle mass. Furthermore, in the study of hospitalized obese children and adolescents, the significant reduction in BF tissue percent was observed through the implementation of similar intervention.[22] In another study, one-dimensional and traditional intervention was considered unsuccessful in fat tissue loss and the multidimensional intervention was considered effective for useful changes of body tissue compositions.[20,23,24]

The traditional obesity interventions have been focused on weight loss and its related indicators such as BMI to evaluate the success of the intervention. However, according to these criteria, many interventions reported limited successes in obesity management. In two intervention studies on weight loss, aligned with the present study results, the physical activity (along with calorie intake limitation or without it) resulted in fat-free mass gain and fat tissue loss, while BMI did not show the significant changes.[25,26] Moreover, Evans et al. reported that small changes in BF percent may not be accurately reflected in BMI.[27]

In a longitudinal study of white children, there was a direct relationship between total BF-free mass index and BMI percentile, whereas FM index and BF percent had more complicated relationships with BMI percentile depending on gender and age and whether BMI percentile was high or low. The results also suggest that BMI percentile changes may not accurately reflect changes in and BF percent in children over time, particularly among male adolescents and children with lower BMI.[10]

Chung reported that BMI has limitation in differentiating changes in BF mass and changes in fat-free mass.[9] Among overweight children, higher BMI levels can be a result of higher fat-free mass (not FM). It has been shown that BMI is not an ideal indicator of obesity since it is significantly influenced by the fat-free mass, especially in obese individuals.[28]

Generally, there is a doubt in regard to using BMI for evaluation and decision-making in control of the obesity. It is suggested that to achieve the best personalized obesity interventions, BF percent has to be considered.[29,30] Previous studies have reported that the precision of BMI as an indicator of fat tissue depends on the severity of obesity.[31,32] BMI is related to FM in healthy adults and it can be responsible for 75% of BF changes, but such relation in some of other age groups such as children is weak.[32] Hence, it is recommended to consider other anthropometric measurements (e.g., bioimpedance analyzer) in children.[12]

Short-time period of the intervention and the absence of adolescent girls in this study can be considered as limitations. Hence, it is recommended to run the next studies with longer intervention and on both boys and girls to increase generalizability of the data.

At the end of this article, it should be noted that this study was the first study in Iran that evaluated the effects of comprehensive health promotion intervention project (based on the Ottawa Charter) on obesity and anthropometric indices.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that the implementation of a comprehensive intervention for obesity management may result in improvements in the body composition indices although these changes may not be reflected in BMI. It is better to use the more accurate evaluation methods such as Simultaneous use of bioimpedance analysis and BMI. It is possible that BMI is not a good indicator in assessment of the success of obesity management intervention. Future studies in this regard are warranted.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and health education and health promotion office of Ministry of Health jointly sponsored the project.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the Health Education and Promotion Department of Ministry of Health (Code 8237). We acknowledge all the university and the schools staff and the study participants for their excellent cooperation.

References

- 1.Morrill AC, Chinn CD. The obesity epidemic in the United States. J Public Health Policy. 2004;25:353–66. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3190035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1499S–505S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemet D, Barkan S, Epstein Y, Friedland O, Kowen G, Eliakim A. Short- and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioral-physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e443–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks EP, Zemel B, Moore RH, Berkowitz RI. Change in body composition during a weight loss trial in obese adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:26–35. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard LM, Wisemandle W, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Guo SS, Siervogel RM. Childhood body composition in relation to body mass index. Pediatrics. 2001;107:344–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Lobstein TI. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2006;1:11–25. doi: 10.1080/17477160600586747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: Childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Clinical practice. Overweight children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2100–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp043052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung S. Body mass index and body composition scaling to height in children and adolescent. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;20:125–9. doi: 10.6065/apem.2015.20.3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demerath EW, Schubert CM, Maynard LM, Sun SS, Chumlea WC, Pickoff A, et al. Do changes in body mass index percentile reflect changes in body composition in children? Data from the Fels Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e487–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM, Pietrobelli A, Goulding A, Goran MI, Dietz WH. Validity of body mass index compared with other body-composition screening indexes for the assessment of body fatness in children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:978–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Venrooij LM, Verberne HJ, de Vos R, Borgmeijer-Hoelen MM, van Leeuwen PA, de Mol BA. Preoperative and postoperative agreement in fat free mass (FFM) between bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:789–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colley D, Cines B, Current N, Schulman C, Bernstein S, Courville AB, et al. Assessing body fatness in obese adolescents: Alternative methods to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Digest (Wash D C) 2015;50:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleary J, Daniells S, Okely AD, Batterham M, Nicholls J. Predictive validity of four bioelectrical impedance equations in determining percent fat mass in overweight and obese children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:136–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Miguel-Etayo P, Moreno LA, Santabárbara J, Martín-Matillas M, Piqueras MJ, Rocha-Silva D, et al. Anthropometric indices to assess body-fat changes during a multidisciplinary obesity treatment in adolescents: EVASYON Study. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:523–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pribyl MI, Smith JD, Grimes GR. Accuracy of the Omron HBF-500 body composition monitor in male and female college students. Int J Exerc Sci. 2011;4:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson M, Lindström B. A salutogenic interpretation of the Ottawa Charter. Health Promotion International. 2008;23:190–9. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29:563–70. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laursen PB, Jenkins DG. The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: Optimising training programmes and maximising performance in highly trained endurance athletes. Sports Med. 2002;32:53–73. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Miguel-Etayo P, Moreno LA, Iglesia I, Bel-Serrat S, Mouratidou T, Garagorri JM. Body composition changes during interventions to treat overweight and obesity in children and adolescents; a descriptive review. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28:52–62. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.1.6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazzer S, Boirie Y, Poissonnier C, Petit I, Duché P, Taillardat M, et al. Longitudinal changes in activity patterns, physical capacities, energy expenditure, and body composition in severely obese adolescents during a multidisciplinary weight-reduction program. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:37–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knöpfli BH, Radtke T, Lehmann M, Schätzle B, Eisenblätter J, Gachnang A, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary inpatient intervention on body composition, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in severely obese girls and boys. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaston TB, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Changes in fat-free mass during significant weight loss: A systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:743–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dao HH, Frelut ML, Oberlin F, Peres G, Bourgeois P, Navarro J. Effects of a multidisciplinary weight loss intervention on body composition in obese adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:290–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiménez-Pavón D, Kelly J, Reilly JJ. Associations between objectively measured habitual physical activity and adiposity in children and adolescents: Systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:3–18. doi: 10.3109/17477160903067601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dulloo AG, Jacquet J. Adaptive reduction in basal metabolic rate in response to food deprivation in humans: A role for feedback signals from fat stores. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:599–606. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans EM, Saunders MJ, Spano MA, Arngrimsson SA, Lewis RD, Cureton KJ. Body-composition changes with diet and exercise in obese women: A comparison of estimates from clinical methods and a 4-component model. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:5–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiquete E, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Ochoa-Guzmán A, Sánchez-Orozco LV, Lara-Zaragoza EB, Basaldúa N, et al. The Quételet index revisited in children and adults. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Lorenzo A, Soldati L, Sarlo F, Calvani M, Di Lorenzo N, Di Renzo L. New obesity classification criteria as a tool for bariatric surgery indication. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:681–703. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carey DG, Raymond RL. Can body mass index predict percent body fat and changes in percent body fat with weight loss in bariatric surgery patients? J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22:1315–9. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816d45ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman KJ. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 3):S56–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Berenson GS, Horlick M. Body mass index and body fatness in childhood. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:618–23. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000171128.21655.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]