Abstract

Drought can severely damage crops, resulting in major yield losses. During drought, vascular land plants conserve water via stomatal closure. Each stomate is bordered by a pair of guard cells that shrink in response to drought and the associated hormone abscisic acid (ABA). The activation of complex intracellular signaling networks underlies these responses. Therefore, analysis of guard cell metabolites is fundamental for elucidation of guard cell signaling pathways. Brassica napus is an important oilseed crop for human consumption and biodiesel production. Here, non-targeted metabolomics utilizing gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were employed for the first time to identify metabolic signatures in response to ABA in B. napus guard cell protoplasts. Metabolome profiling identified 390 distinct metabolites in B. napus guard cells, falling into diverse classes. Of these, 77 metabolites, comprising both primary and secondary metabolites were found to be significantly ABA responsive, including carbohydrates, fatty acids, glucosinolates, and flavonoids. Selected secondary metabolites, sinigrin, quercetin, campesterol, and sitosterol, were confirmed to regulate stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana, B. napus or both species. Information derived from metabolite datasets can provide a blueprint for improvement of water use efficiency and drought tolerance in crops.

Introduction

Plants are sessile organisms that are continuously subjected during their lifecycles to a spectrum of environmental signals and stimuli, including both abiotic factors such as availability of water, light, and nutrients, and biotic factors such as interactions with both beneficial and pathogenic organisms. Accordingly, plants have evolved a suite of molecular mechanisms for external signal perception and transduction, facilitating acclimation to diverse environmental conditions1. Water deficit is one of the major abiotic stresses causing severe losses in crop production2. Drought triggers the biosynthesis, accumulation, and redistribution of abscisic acid (ABA), which promotes stomatal closure, inhibits stomatal opening, and thereby reduces water loss3–7. The pivotal role of stomata in ABA interactions during drought stress has resulted in extensive efforts to elucidate the ABA signaling pathways of guard cells, which border and regulate stomatal apertures. Genetic screens and recent systems biology studies have revealed many signaling events and molecular components that participate in ABA signaling8–15.

Knowledge of ABA signaling in guard cells has been largely derived from the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, which has limited economic value. Brassica napus, also known as oilseed rape or rape, is one of the largest commercial sources of vegetable oil. B. napus is grown worldwide for both human consumption and biodiesel production. B. napus is susceptible to drought stress, which can cause severe reduction in oilseed production16. An improved understanding of molecular responses to ABA in B. napus guard cells will inform genetic engineering and breeding approaches to enhance drought tolerance in crops.

Large scale B. napus guard cell protoplast isolation from B. napus leaves can be conducted with high purity and yield, which provides optimal material for –omics analyses on this single cell type17–19. Using an iTRAQ (isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation)-based comparative proteomics approach, 66 and 38 proteins were found to be significantly induced and suppressed by ABA in B. napus guard cells, respectively. These ABA responsive proteins participate in photosynthesis, metabolism, energy, protein synthesis, stress/defense (antioxidant system and glucosinolate-myrosinase system), membrane and transport processes, and protein folding/transport and degradation10. Recently, 65 thiol-based redox responsive proteins were identified from ABA-treated B. napus guard cells, which highlights redox switches as important regulatory mechanisms in ABA signal transduction in guard cells14.

Metabolites are direct physiological signatures and are highly correlated with phenotypes20; thus, study of cellular metabolomics is also indispensable for complete understanding of stress responses. Stress responsive metabolomes have been investigated in cell culture and in whole plants or whole organs, but rarely in single cell types21,22. One landmark application of metabolomics to study the stress regulated metabolome at the level of the single cell type was an investigation of the ABA responsive metabolic changes in guard cell protoplasts from A. thaliana wild type and heterotrimeric G-protein α subunit mutant, gpa1, using targeted metabolomics with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)12. In targeted metabolomics, paired mass/charge (m/z) ratios of the precursor ion and a selected daughter ion along with the chromatographic retention time, as acquired from analysis of authentic compounds (standards), are employed to identify a metabolite in experimental samples. Eighty-five signaling-related metabolites in A. thaliana guard cells were detected and quantified. The abundance of nearly half of these metabolites (41 out of 85) in wild type guard cells was significantly changed after ABA treatment. Interaction with other hormones, particularly indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), in ABA modulated stomatal movement was revealed, validating phytohormone crosstalk12. These targeted MRM-based profiles of the A. thaliana guard cell metabolome provided the first example of investigating dynamic metabolome changes of a single-cell-type in plants.

Plant metabolomes are highly diverse and have been recognized for their nutritional and medicinal value for centuries23. There are an estimated ~200,000 metabolites produced by the plant kingdom24. To date, however, only ~100 metabolites have been identified in guard cell protoplasts or implicated in guard cell functions18. The majority of these metabolites were identified in the targeted metabolomics study of Jin et al.12, while others were identified in focused studies on a specific metabolite or metabolic pathway. Recently, using guard cell enriched epidermal peels prepared from B. napus leaves, a material relatively easier to obtain, the guard cell metabolite inventory has been expanded to a few hundred metabolites, based on discovery from both targeted and non-targeted metabolomics platforms25,26.

Non-targeted metabolomics provides a complementary approach to targeted metabolomics, with the aim to acquire not only the mass/charge ratio but also the tandem mass spectra of all detected precursor molecules20. Such information facilitates elucidation of the chemical structure of each molecule. Instead of selective detection of a pre-defined metabolite group, non-targeted metabolomics provides global information on the metabolome. To improve our knowledge of the functional guard cell metabolome, here we employed non-targeted metabolomics workflows utilizing two complementary platforms, i.e., gas chromatography (GC)-mass spectrometry (MS) and liquid chromatography (LC)-MS to profile the B. napus guard cell metabolome and its modulation by ABA, resulting in a profile of 390 non-redundant metabolites, 77 of which were ABA responsive. Based on these results, several secondary metabolites were chosen for targeted study and were found to show either antagonistic or additive effects on ABA-induced stomatal closure. Information derived from metabolite datasets will improve our knowledge of ABA signaling in guard cells.

Results

Physiological stomatal response to ABA in B. napus

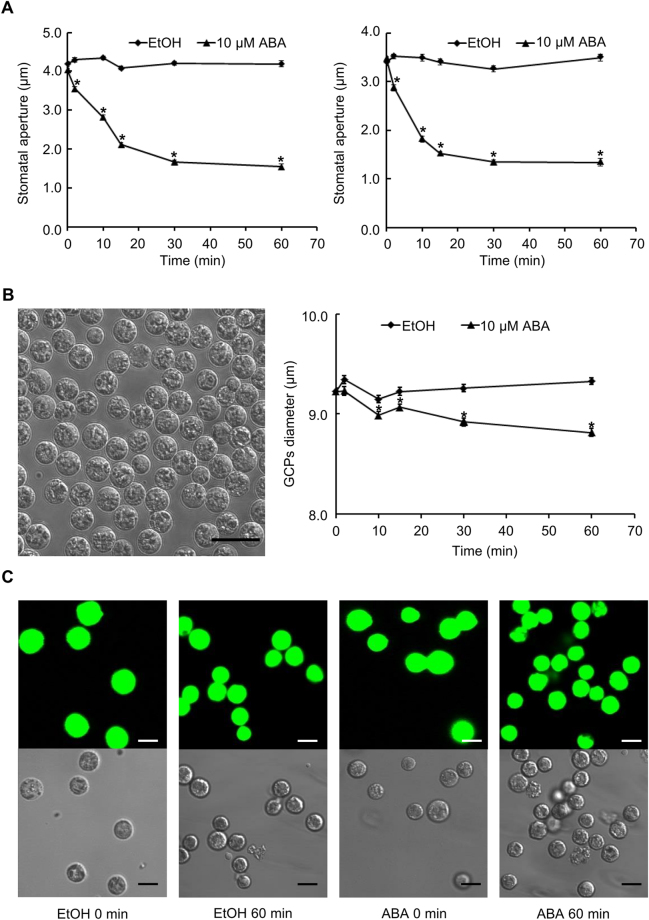

ABA regulated stomatal movement has been observed in a wide range of plant species, including A. thaliana and B. napus 10,12,27,28. Here we first confirmed that 10 µM ABA, a concentration typically used in assays of stomatal responses29–31, is sufficient to induce stomatal closure in both leaf pieces (Fig. 1A) and epidermal peels (Fig. 1A) of B. napus line DH12075. ABA-induced stomatal closure was observed within 2 min and closure was complete within 30 min of treatment in both materials (Fig. 1A). These results indicate the effectiveness of the ABA concentration used for our subsequent metabolomics analyses on B. napus guard cell protoplasts (GCPs). We also confirmed that the solvent for ABA application, ethanol, had no effect on stomatal apertures (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Responses to ABA in B. napus leaves, epidermal peels, and guard cell protoplasts. (A) ABA (10 µM) induces stomatal closure in both leaf pieces (left panel) and epidermal peels (right panel) of B. napus line DH12075. Data are means ± standard errors of 3 independent replicates with 100 ± 5 stomata measured for each sample. (B) ABA-induced shrinkage of B. napus GCPs. Representative image (left); scale bar indicates 25 µm. Data (right) are means ± standard errors of 4 independent replicates with 100 ± 5 GCPs measured for each sample. (C) B. napus GCPs are viable following ABA or ethanol (solvent control) treatment. Samples before treatment (0 min) and after treatment (ethanol (EtOH) 60 min and ABA 60 min) were FDA stained to assess cell viability. Scale bars indicate 10 µm. Asterisks in A and B indicate that ABA treatment differed significantly from the EtOH solvent control (Student’s t test; p < 0.05).

Although epidermal peels have been used for guard cell related –omics studies11,25,26,32, our metabolome analyses were performed on guard cell protoplasts, rather than on epidermal peels, in order to exclude metabolites arising from pavement cells and the cuticle. The viability of isolated GCPs (Fig. 1B) before and after ABA or ethanol treatment was confirmed by fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining (Fig. 1C). ABA responsiveness of the GCPs was evaluated by measuring protoplast diameters over a time course of ABA treatment (Fig. 1B). GCP shrinkage was observed when GCPs were treated with 10 µM ABA as compared to the ethanol (solvent) control (Fig. 1B and C). Together, these results confirm that viability and ABA responsiveness were maintained in B. napus GCPs after protoplasting and treatment.

Metabolome profiling of B. napus guard cells

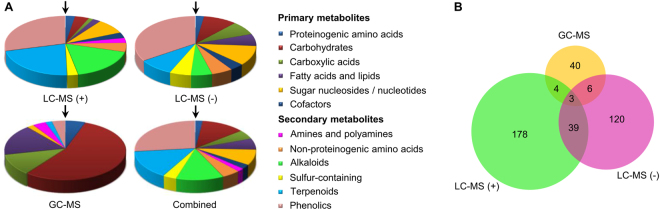

Two major objectives of this study were metabolome profiling and identification of ABA responsive metabolites in B. napus guard cells. We prepared a total of 226 million B. napus GCPs, obtained in ~50 GCP isolations from ~1500 g of B. napus leaves (fresh weight), for our metabolomics analyses. After protoplasting, B. napus GCPs were left untreated or exposed to a time course of ABA treatment (see next section). Pre-separation by gas chromatography (GC) or liquid chromatography (LC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry are robust methods to generate fragmentation patterns that can yield definitive metabolite identification. Here we first employed both GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS to explore the B. napus guard cell metabolome. Five replicates, each with 4–4.5 million untreated GCPs, were prepared and analyzed on the two platforms. For our GC-MS/MS analysis, applying a requirement for metabolite presence in at least 4 out of the 5 replicates of untreated sample (0 min) coupled with an identification score over 70 arising from a NIST 11 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA) mass spectral library search as the threshold, led to identification of a total of 53 metabolites. The majority of these metabolites (48 out of 53) are primary metabolites, as is expected for GC-MS analysis33–35, and fall into the categories of carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, fatty acids and lipids (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 1). For our LC-MS/MS analysis, the same requirement for presence in at least 4 out of the 5 replicates of untreated sample (0 min), coupled with an identification score threshold of ≥0.6 in MassBank, led to an identification of a larger number of metabolites (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 1). Under positive ion mode, 224 metabolites were identified, with nearly 80% involved in secondary metabolism. In particular, a number of carotenoids (subgroup of terpenoids) and flavonoids (subgroup of phenolics) were detected in positive mode (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Table 1). Under negative ion mode, 168 metabolites were identified, of which nearly two thirds were secondary metabolites, with the dominant group being phenolics (58 out of 168), followed by sugar nucleosides/ nucleotides, carbohydrates and carboxylic acids (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Metabolomic profiling using complementary platforms resulted in identification of 390 non-redundant metabolites in B. napus GCPs. (A) Classification of metabolites identified from each platform, mainly based on structural characteristics101. The metabolite categories are listed in the figure caption in the clock-wise order in which they appear in the figure, starting with “Proteinogenic amino acids” at the 12 o’clock position (arrow) in all four pie charts. No metabolites in the category of “Amines and polyamines” were identified by the LC-MS (−) platform. No metabolites were identified by GC-MS in the categories of “Cofactors”, “Non-proteinogenic amino acids”, “Alkaloids”, or “Sulfur-containing”. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of metabolites identified from each platform.

In total, 390 non-redundant metabolites were identified by our criteria in untreated B. napus guard cells. Each of the three datasets from GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS positive and negative ion modes contain a unique subset of metabolites and thus these methods are complementary (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Table 1). Only three metabolites, phenylalanine, ferulic acid, and sinapic acid, were identified by all three acquisition methods (Fig. 2B). Only 13 metabolites were found in common between GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS, while 42 were identified by both positive ion mode and negative ion mode in LC-MS/MS (Fig. 2B).

The KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) PATHWAY database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) contains a collection of manually compiled KEGG pathway maps representing molecular interaction and reaction networks of metabolism and other functions, derived from multiple organisms, including A. thaliana, B. napus, and B. rapa, a parental ancestor of B. napus. Of the metabolites we identified, there were 286 metabolites with a KEGG compound index. Of these, 124 metabolites mapped to the metabolic pathways available in KEGG from the reference species B. napus. The same set of metabolites also mapped to the metabolic pathways of B. rapa in KEGG. Distribution of identified metabolites on the metabolic map indicates that a wide variety of metabolic pathways are reseprented in the B. napus guard cell metabolome (Supplemental Fig. S1 and Supplemental Table 1). There are several reasons for incomplete mapping of all of our identified metabolites: 1) not all metabolites are indexed in KEGG. For example, a few of the flavonoids identified in our profiling, especially those in the glycosidic form, are not available in KEGG (Supplemental Table 1), which is consistent with previous observations on other plant metabolomes36. 2) KEGG pathway maps are based on experimental knowledge of metabolism, which can be far from complete.

The Plant Metabolic Network (PMN, http://www.plantcyc.org/) is another valuable compendium of plant compound information37. Of the metabolites we identified, 128 are included in the B. rapa compound list from PMN, which contains over 1700 non-redundant metabolites. For the 262 metabolites without a hit in the PMN B. rapa compound list, 92 have one or more chemical derivatives in the PMN list (Supplemental Table 1). Together with those metabolites mapped to KEGG pathways, 174 metabolites known to be present in B. rapa and/or B. napus are present in our metabolome profiling, suggesting considerable metabolite diversity in B. napus guard cells. Additionally, 29 metabolites out of the 390 metabolites we identified in B. napus guard cells were also detected in a previous, targeted study on A. thaliana guard cells that quantified a set of 85 specific metabolites12 (Supplemental Table 1). Misra et al.25 and Geng et al.26 recently reported 268 and 358 metabolites, respectively, in the metabolite profiling of guard cell enriched epidermal peels from B. napus, in studies of metabolome responses to bicarbonate and elevated CO2, respectively. Our identified metabolome had an overlap of 62 and 74 metabolites with those datasets, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Our metabolome profile (390 metabolites; 225 of which were not previously identified in other guard cell metabolome profiling datasets12,25,26) thus significantly expands our knowledge regarding the metabolome of this specialized cell type.

Identification of ABA-responsive metabolic signatures in B. napus GCPs

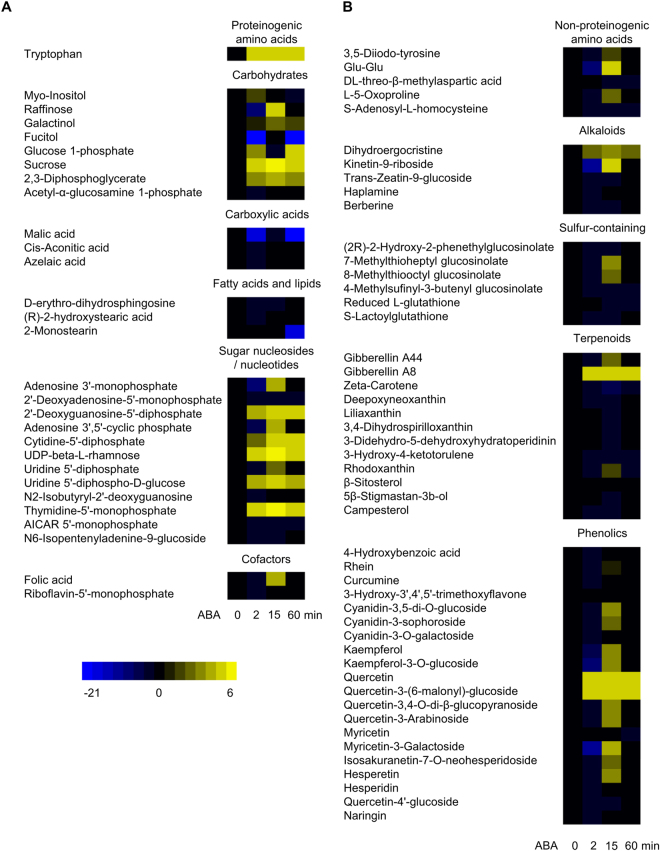

B. napus GCPs were treated with ABA at a final concentration of 10 µM for 0 (i.e., untreated GCPs; results discussed above), 2, 15, or 60 min, respectively. Given that ethanol (EtOH, solvent control) did not regulate stomatal movement in B. napus (Fig. 1A) and no significant changes in metabolites caused by ethanol were detected in A. thaliana guard cells12, only GCPs treated with ethanol for 15 min were prepared in our experiment. Five replicates of each sample, i.e., 0 min, ABA 2 min, ABA 15 min, ABA 60 min, and EtOH 15 min, were prepared and analyzed on GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS in parallel. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the 0 min and EtOH 15 min groups cluster together, whereas ABA treated groups are distinguished from 0 min and EtOH 15 min, indicating the ABA treatment as the major factor contributing to the cluster segregation (Supplemental Fig. S2). To identify responsive metabolites, we imposed a threshold of p value ≤0.05 in Student’s t test and at least 20% in fold change38,39. For these analyses, each treatment sample, i.e., ABA 2 min, ABA 15 min, ABA 60 min, and EtOH 15 min was compared to the 0 min sample. EtOH treatment for 15 min caused changes in only 12 metabolites, with 10, 1, and 1 identified from GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS positive mode, and LC-MS/MS negative mode, respectively (Supplemental Table 2). Eleven of these metabolites, for example, xylitol and palatinose, were also found in our ABA responsive dataset; these metabolites were not designated as ABA-regulated, due to their EtOH responsiveness. After combining the GC dataset with the two LC datasets, 17, 66, and 18 metabolites were found to be ABA responsive at time points 2 min, 15 min, and 60 min respectively, as compared to 0 min (Supplemental Table 2). The abundance changes of all these metabolites (77 unique metabolites in total) at different time points under ABA treatment are represented by heat maps (Fig. 3). None of these 77 metabolites was absent (i.e., no detection) in untreated (0 min) samples but present in ABA-treated samples, although some unidentified MS peaks appeared upon ABA treatment. Among the ABA responsive metabolites, 8, 27, and 48 metabolites were revealed by GC, LC positive mode, and LC negative mode, respectively. There was only one metabolite (galactinol) common to GC and LC negative mode, no metabolites common to GC and LC positive mode and only 5 metabolites common to LC positive mode and negative mode (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-ribofuranosyl 5′-monophosphate, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate, 2′-deoxyadenosine-5′-monophosphate, S-lactoylglutathione, and kaempferol) (Supplemental Table 2), again illustrating the value of multiple analysis methods. The major groups of the ABA responsive metabolites were phenolics (mostly flavonoids), carbohydrates, terpenoids (mostly tetraterpenoids), sugar nucleosides/nucleotides, and sulfur-containing metabolites (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 3.

Primary (A) and secondary (B) metabolites responsive to ABA at different time points in B. napus GCPs. At 2, 15, and 60 min heat maps represent log2 of fold change, i.e., the log2-transformed metabolite abundance (peak area) at each time point divided by the level at 0 min; a 0 min column is also provided for comparison. All metabolites depicted were significantly changed at one or more time points (2 min, 15 min, and 60 min) of ABA treatment. Abbreviations: UDP: uridine diphosphate; AICAR: 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-ribofuranosyl.

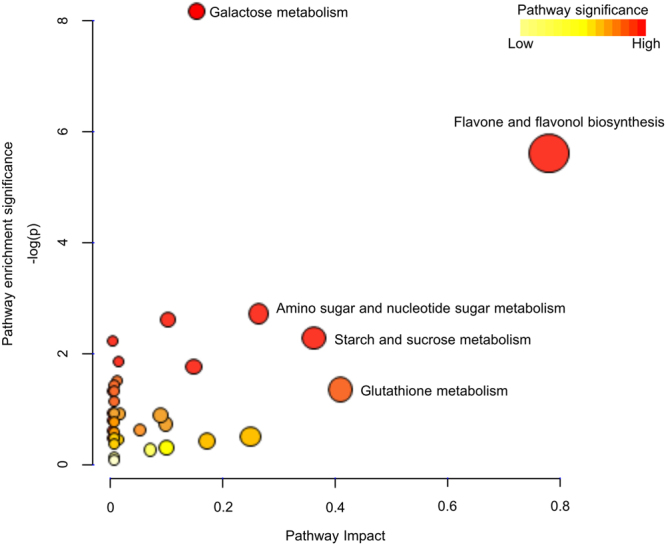

A pathway enrichment analysis was performed using all available KEGG IDs of the ABA responsive metabolites (58 out of 77) against the KEGG A. thaliana reference metabolome using MetaboAnalyst 3.040. Figure 4 shows all identified pathways from pathway enrichment analysis, which assesses the over-representation of inquiry compounds in known pathways, and their pathway impact values from pathway topology analysis, which indicate the importance of the identified metabolites to that pathway41 (Supplemental Table 3). Enriched pathways with high impact include flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism (Fig. 4). Flavone and flavonol are two subgroups of flavonoids that are widely distributed secondary metabolites in higher plants42. The majority (15 out of 17) of the flavonoids were upregulated by ABA at 15 min (Fig. 5A and B; Supplemental Table 2). Sugar metabolism is also highly impacted by ABA treatment (Fig. 4). For example, an increase in sucrose and glucose 1-phosphate was observed in B. napus GCPs under ABA treatment (Fig. 3). Uridine 5′-diphosphate (UDP), UDP-glucose, and UDP-rhamnose also showed significant upregulation by ABA treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Metabolic pathways affected by ABA treatment in guard cells revealed by pathway analysis. x axis represents the impact of the identified metabolites on the indicated pathway. y axis indicates the extent to which the designated pathway is enriched in the identified metabolites. Values were ascertained from MetaboAnalyst. Circle colors (see color scale for reference) indicate pathway enrichment significance. Circle size indicates pathway impact.

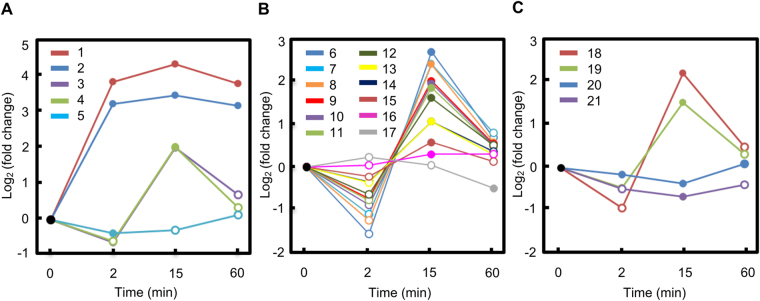

Figure 5.

Abundance changes along the time course of ABA treatment for quercetin and quercetin derivatives (A), non-quercetin flavonoids (B), and glucosinolates (C). Metabolites 1–22 are: 1: quercetin-3-(6″-malonyl)-glucoside; 2: quercetin; 3: quercetin-3-arabinoside; 4: quercetin-3,4′-O-di-beta-glucopyranoside; 5: quercetin-4′-glucoside; 6: myricetin-3-galactoside; 7: kaempferol; 8: kaempferol-3-O-glucoside; 9: cyanidin-3,5-di-O-glucoside; 10: hesperetin; 11: isosakuranetin-7-O-neohesperidoside; 12: cyanidin-3-sophoroside; 13: hesperidin; 14: naringin; 15: cyanidin-3-O-galactoside; 16: 3-hydroxy-3′,4′,5′-trimethoxyflavone; 17: myricetin; 18: 7-methylthioheptyl glucosinolate; 19: 8-methylthiooctyl glucosinolate; 20: (2 R)−2-hydroxy-2-phenethylglucosinolate; 21: 4-methylsufinyl-3-butenyl glucosinolate. Solid data points indicate statistically significant changes upon ABA treatment (Student’s t test; p value < 0.05) compared to 0 min data.

Effects of flavonoids, glucosinolates, and sterols in stomatal responses to ABA in A. thaliana and B. napus

Multiple flavonoids were identified as ABA-responsive in B. napus guard cells (Supplemental Table 2, Fig. 3, and Fig. 5A and B), most of which were glycosylated, i.e., linked with a sugar moiety. Although such conjugated metabolites are generally presumed to be inactive43, one study found that flavonoid glycosides such as quercetin 3-O-glucoside and kaempferol 3-O-glucoside exhibit radical scavenging activities, a feature that would suppress ROS42, which are known to promote stomatal closure44,45. We observed that quercetin and quercetin-3-(6″-malonyl)-glucoside were strongly induced by ABA (Fig. 5A). Two other quercetin derivatives, quercetin-3,4′-O-di-beta-glucopyranoside and quercetin-3-arabinoside were also induced while quercetin-4′-glucoside was slightly repressed (Fig. 5A and Supplemental Table 2). All of the other 12 non-quercetin related flavonoids were significantly induced by ABA treatment at 15 min except for myricetin (Fig. 5B and Supplemental Table 2).

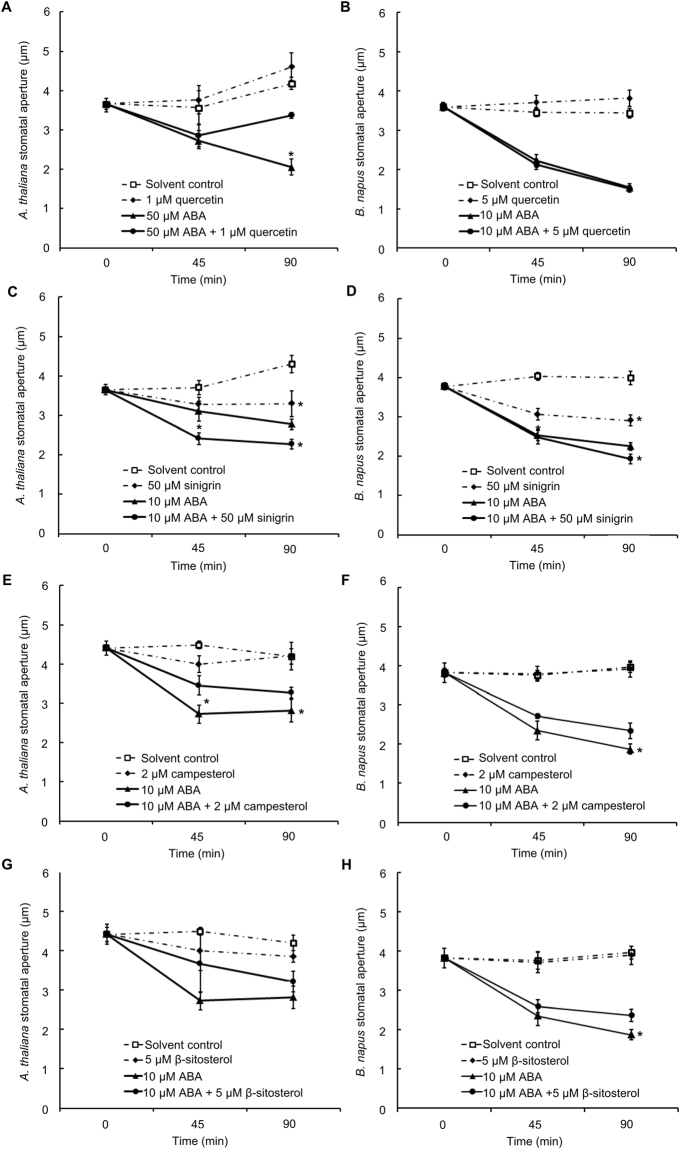

Based on the results of our large-scale metabolite analyses and previous observations46,47, we hypothesized that the identified flavonoids would modulate stomatal movements. As a test of this hypothesis, we applied a non-glycosidic form of one of the strongly ABA-upregulated flavonoids, quercetin, to investigate its effect on stomatal movement and its regulation by ABA in A. thaliana. Based on quercetin measurement in the leaves of A. thaliana 47,48, we estimated that in vivo quercetin concentration is close to 1 µM. In Arabidopsis leaves, application of 1 µM quercetin caused a slight increase in stomatal aperture compared to solvent control after 90 min treatment; however, without statistical significance (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, ABA-induced stomatal closure was opposed by 1 µM quercetin (Fig. 6A), suggesting an antagonistic role of quercetin in the ABA signaling pathway. A significant effect of quercetin was observed at 90 min, implying the interaction of quercetin with ABA either as a late stage signaling event or a sustained process. We also tested the effect of quercetin in B. napus leaf pieces. However, an antagonistic effect of quercetin in ABA (10 µM) -induced stomatal closure was not observed in B. napus even at concentrations up to 5 µM (Fig. 6B). The inconsistency of quercetin effect between the two species might be caused by species-dependent sensitivity to the metabolite tested.

Figure 6.

Effects of quercetin, sinigrin, campesterol, and β-sitosterol on stomatal apertures in A. thaliana (A,C,E and G) and B. napus (B,D,F and H) leaves. Data are means ± standard errors of at least 4 independent replicates with 100 ± 5 stomata measured for each sample. Asterisks indicate a significant effect of addition of the secondary metabolite (Student’s t test; p < 0.05).

Several glucosinolates were also found to be responsive to ABA in our guard cell metabolomes, with 7-methylthioheptyl glucosinolate and 8-methylthiooctyl glucosinolate significantly increasing after ABA treatment (Fig. 5C and Supplemental Table 2). The glucosinolate-myrosinase system is a defensive mechanism uniquely present in some plant families, including the Brassicaceae 49. Stomatal movement modulation by components in this system also has been recognized50–52. To investigate glucosinolate regulation of stomatal movement, we applied an allyl-glucosinolate, sinigrin, separately or with ABA, to A. thaliana and B. napus leaves. Sinigrin is a naturally occurring metabolite in A. thaliana and B. napus, and is hydrolyzed by myrosinases into allyl isothiocyanate and allyl cyanide53,54. Sinigrin-induced stomatal closure and an additive effect with 10 µM ABA in promotion of stomatal closure were observed with statistical significance in both A. thaliana (Fig. 6C) and B. napus (Fig. 6D).

Several phytosterols (β-sitosterol, 5β-stigmastan-3b-ol, and campesterol) were downregulated in guard cells upon ABA treatment (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 2). We applied campesterol (2 µM), either separately or with ABA (10 µM), to A. thaliana and B. napus. In both species, an antagonistic effect of campesterol on ABA-induced stomatal closure was observed (Fig. 6E and F). The effect of another phytosterol, β-sitosterol was also tested in the ABA-induced stomatal closure of A. thaliana and B. napus. An antagonistic effect of β-sitosterol (5 µM) in ABA- induced stomatal closure was observed in B. napus (Fig. 6H) but not consistently in A. thaliana (Fig. 6G).

Discussion

Complementary GC-MS and LC-MS platforms together with simplified extraction enhances coverage in metabolome profiling

Largely due to the differences in the ionization techniques and columns for molecule separation, GC-MS and LC-MS each exhibit detection biases for certain classes of metabolites. Temperature gradients for separation and electron ionization are commonly used in GC-MS, and primary metabolites, such as amino acids, carbohydrates, organic acids, and fatty acids are the main categories of metabolites detected with GC-MS33. LC-MS usually separates molecules based on their polarity and uses soft electrospray ionization, which in practice covers a wider range of metabolites, including plant secondary metabolite groups such as alkaloids, phenolics, and flavonoids33. These platform biases were also observed in our study: the majority of metabolites identified with GC-MS were primary metabolites whereas LC-MS analyses detected both primary and secondary metabolites (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 1). The three analysis conditions are complementary and overall 390 non-redundant metabolites were identified, making this dataset one of the largest to date for a plant single cell type22,55.

Ionization in LC-MS can generally be divided into positive mode, in which samples are protonated, and negative mode, in which samples are deprotonated. Typically, certain categories of metabolites can be preferentially resolved under a certain mode. For example, in our experiments, carotenoids were only detected under positive mode (Supplemental Table 1), mostly with the MS precursor in the radical cation form [M]*+ rather than the protonated form [M + H]+, a phenomenon that has been observed before56. On the other hand, more acids were identified under negative mode, which might be due to the prone-to-deprotonate feature of acids (Supplemental Table 1). Therefore, as previously known and as we observed in our study, no single analytical instrument is entirely robust to cover the whole metabolome profile. For broad coverage, it is necessary to utilize multiple platforms for metabolome profiling.

In addition to the choice of the instrumentation platforms, the selection of the metabolite extraction protocol is another key factor that influences metabolome coverage. Practically, only a fraction of the entire metabolome can be resolved, in part depending on the composition of the extraction solution. For example, inclusion of chloroform in the extraction solvent was found to be counterproductive in an untargeted LC-MS metabolomics workflow33. Additionally, metabolites, even if successfully extracted, might not be detected by mass spectrometry due to failure to be dissolved by the loading buffer prior to the analysis. Therefore, an unbiased and efficient extraction protocol is critically important to successful metabolome profiling. Although responsive to stimuli, GCPs lack cell walls, and so can be easily disrupted for metabolite release. Accordingly, in this study metabolites were extracted from GCPs simultaneously with derivatization, including heating and shaking steps for GC-MS/MS analysis, and vortexing with loading buffer for LC-MS/MS analysis. This procedure dramatically reduced sample processing time and potential sample loss caused by transfers during extraction.

Metabolite identification and annotation

In the early days of mass spectrometry based metabolomics, m/z was used for identification, sometimes together with chromatographic retention time. A major disadvantage of this type of identification is that isomers and stereoisomers cannot be differentiated due to their identical mass and occasional co-elution on chromatography57. With the advent of tandem mass spectrometry, fragmentation patterns (MS/MS or MSn) of a compound provide another important, and often defining, feature for metabolite identification58. Databases with mass spectral information are essential references for metabolomics studies. MassBank is the first public database of metabolite mass spectra, and over 50% are MS/MS or MSn spectra. These spectra were acquired on a variety of instruments (~30 types) under independent conditions and contributed by ~30 research groups worldwide. In MassBank, the function “Spectrum Search” retrieves spectra that are similar to the experimentally-acquired inquiry spectrum, and a similarity score (within the range 0–1) is calculated to indicate the confidence of identification. MassBank shows superior performance for metabolite identification using tandem mass spectral search59,60. Due to its public availability, large number of reference spectra, and user-friendly scoring system, we chose MassBank to annotate the features acquired from our LC-MS/MS analysis. Using 0.6 as the threshold for similarity score61, we identified 224 non-redundant compounds from 2620 monoisotopic features acquired under positive mode and 168 non-redundant compounds from 2327 monoisotopic features acquired under negative mode. Together with the data from our GC-MS/MS analysis, identification of these metabolites greatly improves our knowledge of the guard cell metabolome.

B. napus guard cell metabolome is related to stomatal function

Unlike the guard cell transcriptome8,11 and proteome10,14, the guard cell metabolome has remained largely unknown, in part due to the greater difficulty of sample preparation and technical limitations in metabolomics18. Here we employed complementary non-targeted metabolomics platforms for guard cell metabolome profiling and identified metabolites of both primary and secondary metabolism.

Primary metabolites are central components of the B. napus guard cell metabolome (Supplemental Table 1 and Fig. 2). Previous studies suggested that guard cells contain fewer chloroplasts and possess lower photosynthetic capability than mesophyll cells62. Here we identified a variety of sugars including monosaccharides (fructose and glucose), disaccharides (sucrose), and polysaccharides in B. napus guard cells (Supplemental Table 1). These carbohydrates might have been either previously synthesized elsewhere and transported into guard cells or generated by guard cell photosynthesis62. Guard cells contain abundant mitochondria and exhibit high rates of mitochondrial respiration63,64 and energy related proteins were also found to be enriched in B. napus guard cells17. The carboxylic acids and fatty acids found in our metabolite analysis are potential carbon sources to fuel stomatal movement, consistent with a recent report on the importance of triacylglycerol metabolism to blue light-induced stomatal opening65.

Plant secondary metabolites are usually low in abundance but with important functions not only for plants but also for human nutrition and medicine66. Major groups of plant secondary metabolites include phenolics, terpenoids, and nitrogen-containing metabolites (such alkaloids and amines). Flavonoids are a large family of plant secondary metabolites with benzo-γ-pyrone structure67. We identified a total of 76 flavonoids in B. napus guard cells (Supplemental Table 1). Flavonoids have antioxidant activity and ROS, e.g., H2O2 and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), e.g., NO, not only serve as secondary messengers in guard cell signal transduction but also cause mild oxidative stress in guard cells14,44. It can be speculated that flavonoids might participate in redox homeostasis maintenance for proper responsiveness of the guard cell system47,68,69.

Glucosinolates are hydrophilic nitrogen and sulphur containing glycosides that participate in responses to abiotic and biotic stresses49,70. At least 11 different glucosinolates have been identified and quantified in B. napus leaves71. We identified 7 aliphatic and 2 aromatic glucosinolates in B. napus guard cells (Supplemental Table 1), some of which were previously detected in other organs of B. napus or related species. For example, glucoerucin was detected in B. napus hypocotyl and cotyledon but not in seeds72; 3-methylthiopropyl and 3-methylsulfinylpropyl glucosinolates were detected in B. oleracea seeds73.

Plant sterols and steroid hormones are essential for plant development, reproduction, and responses to various abiotic and biotic stresses, including drought, salt, heat, cold, hypoxia, pesticides, and heavy metals74. Several A. thaliana brassinosteroids (BR)-related mutants are affected in stomatal function75,76 and a possible interaction between BR and ABA has been suggested77. B. napus guard cells are rich in steroids (Supplemental Table 1), suggesting a possible correlation to stomatal function in stress responses.

A recent study observed that ~45% stomata of a guard cell specific chlorophyll-deficient mutant were continuously closed, suggesting that photosynthesis is critical to maintain turgor in guard cells78. Additionally, the guard cell chloroplast is a site for light and CO2 sensing in guard cells62,79,80. Identification of tetraterpenoids, including several carotenoids, provides metabolite details for guard cell chloroplasts (Supplemental Table 1). For example, violaxanthin is a key component in both carotenoid biosynthesis and the xanthophyll cycle, and has been detected previously in Vicia faba guard cells81,82. Taken as a whole, the metabolome profiling revealed by non-targeted metabolomics is a valuable resource to improve our understanding of guard cell function.

ABA responsive metabolites revealed by non-targeted metabolomics reveal new insights on ABA signaling in guard cells

Targeted and non-targeted metabolomics are complementary discovery approaches. The targeted strategy, analogous to reverse genetics, is powerful for hypothesis driven studies with an a priori list of metabolites of interest, and is especially useful for low abundance metabolites such as phytohormones. The disadvantage of targeted metabolomics is that it will not provide a global view of the response and will miss metabolites that were not previously hypothesized to be of interest. Non-targeted metabolomics, analogous to forward genetics, does not suffer from these shortcomings.

There are both similarities and differences between the results of our present non-targeted study on B. napus and our previous targeted metabolomics study on ABA treated A. thaliana guard cells12. Decreases in malic acid and zeatin glucoside, as well as an increase in tryptophan were observed in ABA treated B. napus guard cells (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). This is consistent with our previous targeted metabolomics study on the ABA-regulated metabolome of A. thaliana guard cells12. Up-regulation of gibberellins (A8 and A44) and quercetin was found in our study and similar trends of gibberellins (A3 and A4) and quercetin were detected by Jin et al.12 but without statistical significance. One difference between the two studies is that an increase of sucrose was observed in B. napus guard cells but a decrease in sucrose was observed in A. thaliana guard cells following ABA application (Fig. 3)12. These differences may have arisen from differences in species and/or ABA concentrations used for treatment.

Hormone crosstalk during ABA signaling has been observed in physiological, transcriptional, and targeted metabolomics studies12,83. In our study only a few phytohormones were identified, such as jasmonic acid, zeatin, and gibberellins (Supplemental Table 1). Other hormones such as auxin and ABA precursors, however, were not detected.

In our study, 77 metabolites were identified to be ABA responsive in B. napus guard cells, including 29 primary metabolites and 48 secondary metabolites. A majority of them (67 out of 77) showed significant changes at 15 min, while fewer showed significant changes at the beginning (17 at 2 min) or the end (18 at 60 min) of treatment. Indeed, PCA analysis suggests that the ABA-regulated metabolome at 60 min may be returning to the baseline 0 min state (Supplemental Fig. S2). These dynamics suggest that ABA causes temporal and in some cases transient changes in metabolite abundance in B. napus guard cells, as was also observed in the targeted metabolomics analysis on the ABA-regulated guard cell metabolome in A. thaliana 12.

ABA signaling pathways in guard cells have been intensively studied due to ABA’s relevant roles in plant stress responses3,4,7. The role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as secondary messengers in ABA signal transduction has been well documented3,44,45. ROS bursts also cause oxidative stress and change cellular redox homeostasis. Small molecules such as ascorbic acid and glutathione participate in the regulation of ROS homeostasis in plants84. A decrease in glutathione in response to ABA was observed in both B. napus guard cells (Fig. 3) and A. thaliana guard cells12. Abundance increases in protein components of ROS scavenging, e.g., ascorbate peroxidase and glutathione peroxidase as well as redox status of cysteines in a variety of proteins were observed in ABA-treated B. napus guard cell protoplasts in previous proteomic studies10,14. Taken together, these metabolomics and proteomics results add to results from genetic and pharmacological approaches44,85 that implicate redox homeostasis as an important regulatory mechanism associated with ABA signaling in guard cells.

In plants, flavonoid accumulation has been observed to be associated with oxidative stresses induced by environmental stimuli67. Pathway enrichment analysis revealed that flavone and flavonol biosynthesis was highly impacted by ABA treatment in B. napus guard cells (Fig. 4). More specifically, we observed upregulation of 15 flavonoids upon ABA treatment (Figs. 3 and 5, and Supplemental Table 2). This is consistent with the observation that a flavonol synthase (AT5G08640), a chalcone-flavanone isomerase (AT5G05270), and a riboflavin biosynthesis protein (AT2G22450) were induced by ABA at the transcript level in A. thaliana guard cell-enriched epidermal peels11. Moreover, it was recently reported that an A. thaliana chalcone synthase null mutant tt4-2, which is defective in flavonol synthesis, is hypersensitive to ABA in ABA induced stomatal closure. The authors propose that flavonol accumulation in wild-type guard cells suppresses ROS elevation and moderates stomatal closure47. In another study, accumulation of anthocyanins was observed in Arabidopsis lines pap1-D with constitutive expression of PAP1 (Production of Anthocyanin Pigment1) and these lines were more drought tolerant compared to wild type and the flavonoid-deficient mutant tt4 46. Higher levels of total flavonols and total anthocyanins were detected in lines with overexpression of both PAP1 and MYB12/PFG1 (Production of Flavonol Glycosides 1). These lines showed comparable drought tolerance to pap1-D but higher survival rate after re-watering46. These results suggested a link between flavonoid accumulation and drought/ABA responses. However, a direct effect of flavonoids on ABA-induced stomatal closure has not been studied yet. Here we observed that ABA-induced stomatal closure is reduced by 1 µM quercetin in Arabidopsis (Fig. 6A), suggesting an antagonistic role of quercetin in the ABA signaling pathway. Together with the observation that several flavonoids were induced by ABA (Figs 3 and 5), our metabolite analysis supports the hypothesis47,69 that flavonoid accumulation in guard cells might function in a negative feedback process to mitigate or ensure only transient ABA-induced ROS elevation.

Sugar metabolism was also highly impacted by ABA treatment (Fig. 4). A >100 fold increase of sucrose was observed at 15 min of ABA treatment and the upregulation was maintained along the time course. Given that our analyses were perform on isolated guard cell protoplasts, the detected sucrose must be endogenous to guard cells, and might originate from guard cell photosynthesis or from starch degradation. The transcripts of two sucrose synthases (SUS1 and SUS3), two sucrose-phosphate synthases (SPS1 and SPS3F), as well as an α-glucan, water dikinase required for starch degradation (SEX1) were all induced by ABA in A. thaliana guard cell enriched epidermal peels11. Based on a sucrose standard curve established on the same GC-MS as used for non-targeted analysis, the sucrose concentration is estimated to be 10–15 µM at 0 min and ~2 mM at 15 min of ABA treatment in B. napus guard cells, respectively. Such an increase will not dramatically contribute to osmolarity increase inside the cell. It has been reported that external application of sucrose and its catabolic products glucose and fructose are sensed within guard cells by hexokinases to stimulate stomatal closure in tomato86; those results, together with ours, suggest that sucrose may play a role in transduction of the ABA signal in guard cells.

Sucrose might also be a carbon source for energy production during stomatal closure, which has been shown to be an energy-requiring process62,87. An increase in glucose 1-phosphate was also observed in B. napus GCPs under ABA treatment (Fig. 3). The phosphorylated glucose could be catabolized for ATP production through glycolysis and/or tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to energize stomatal closure88. Additionally, one TCA cycle product, malic acid (malate) was present at 0 min but was not detectable at the end of ABA treatment (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 2), suggesting the catabolism or export of this osmoticum during stomatal closure89, e.g., through R-type and S-type anion channels, which are permeable to malate90,91.

Glucosinolates are nitro-sulphate secondary metabolites that are present in many Brassicaceae species, including A. thaliana and B. napus. Glucosinolates are degraded by myrosinases, and resulting hydrolysis products such as thiocyanates, isothiocyanates and nitriles are known to deter insects and pathogens49. Involvement of the glucosinolate-myrosinase system in stomatal movement regulated by abiotic stress was not recognized until a report of a myrosinase mutant, tgg1, exhibiting hyposensitivity to ABA inhibition of guard-cell inward K+ channels and stomatal opening50. A subsequent study suggested that A. thaliana myrosinases TGG1 and TGG2 function downstream of ROS production and upstream of cytosolic Ca2+ elevation during ABA and MeJA signaling in guard cells51. Methionine chain elongation of glucosinolates is catalyzed by isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPMDH) and A. thaliana ipmdh mutants exhibit hyposensitivity in both ABA promotion of stomatal closure and ABA inhibition of opening14. Additionally, stomatal closure induced by glucosinolate hydrolysis products such as isothiocyanate was also reported52.

Consistent with previous reports suggesting that glucosinolate hydrolysis products function analogously to ABA in stomatal aperture regulation, we observed sinigrin-induced stomatal closure that was additive with ABA in both A. thaliana and B. napus (Fig. 6B and D). One degradation product of sinigrin, allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), was found to induce stomatal closure in both A. thaliana and V. faba accompanied by ROS and NO production52,92. AITC-induced cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation was also observed in A. thaliana guard cells52. Therefore, the effect of sinigrin that we observe here might be mediated through stimulated production of these second messengers, which are known to promote stomatal closure.

Plant sterols (phytosterols) are structurally related to cholesterol with differences in side chains93. Phytosterols are membrane components with various biological functions, including regulation of membrane fluidity and permeability94. The most common natural phytosterols species include campesterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, and brassicasterol94. Linkage between phytosterols and drought tolerance has been documented in several plant species95. For example, elevation in contents of sterols (campesterol, stigmasterol, and β-sitosterol) and steryl esters, along with enhanced enzyme activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, a key enzyme of phytosterol biosynthesis, were observed in rice seedlings under drought stress95. Transgenic rice with the SQUALENE SYNTHASE (SQS) gene disrupted by RNAi had lower sterol and BR content, and showed enhanced drought tolerance96. In the present study, decreases in β-sitosterol, 5β-stigmastan-3b-ol, and campesterol were observed in ABA treated B. napus guard cells (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 2). These results seem contradictory to the observation in rice95. However, this might be due to the differences in material (GCPs vs. whole plant) and treatment duration (1 h vs. days). The decreases in sterol content we observed in GCPs might be caused by membrane recycling due to ABA-induced cellular shrinkage (Fig. 1B). External application of phytosterols, in general, had an antagonistic effect in ABA-induced stomatal closure (Fig. 6E, F, and H). Such exogenous phytosterols might contribute to maintenance of membrane stability under ABA treatment or retard ABA signal perception and transduction.

Conclusions

Non-targeted metabolomics provides robust discovery workflows to reveal metabolome profiles and their roles in plant stress responses. Here we employed both GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS platforms and identified a total of 390 non-redundant metabolites in B. napus guard cells, which have not previously been subjected to metabolome profiling. Temporal metabolite changes upon ABA treatment were also investigated. An overall increase in flavonoids, divergent changes in glucosinolates, and a decrease in phytosterols upon ABA treatment were detected in B. napus guard cells. Involvement of quercetin, sinigrin, β-sitosterol, and campesterol in regulation of stomatal closure was confirmed in A. thaliana and/or B. napus, demonstrating the conserved nature of several of the metabolite-based regulatory mechanisms. ABA responsive metabolic signatures are potential targets for engineering enhanced drought tolerance for crop improvement.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth, guard cell protoplasting, and ABA treatment

Brassica napus double haploid line (DH12075) plants were grown under an 8-hour-day (22 °C) /16-hour-night (20 °C) cycle with light intensity 125 µmol·m−2·sec−1. Fully expanded leaves from 6-7 week old plants were used for guard cell isolation as previously described17,19. Briefly, ~30 g of fully expanded leaves with main veins excised were blended 4-5 times for 30 s each in cold tap water using a blender (Oster Inc., USA). After blending, epidermal peels were washed thoroughly with tap water and transferred to 200 mL of the first enzyme solution: 0.1% (w/v) PVP-40, 0.25% (w/v) BSA fraction V, 0.7% Cellulase R-10, and 0.02% Macerozyme R-10, prepared in 55% (v/v) basic solution. Basic solution contains 0.55 M sorbitol, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 10 µM KH2PO4, 10 mM MES-Tris, pH 5.5. Peels were digested for 1 h at 28-29 °C with a shaking speed of 140 rpm. Peels were then retained by filtration with 100 µm mesh and transferred to the second enzyme solution: 200 mL, 0.25% (w/v) BSA fraction V, 1.1% (w/v) Onozuka RS cellulase, and 0.02% (w/v) Pectolyase Y-23 prepared in 100% basic solution. Digestion was for ~1.5 h at 20 °C with a shaking speed of 50 rpm. Peels were then retained on 30 µm nylon mesh and were rinsed with 600–800 mL basic solution, resulting in a filtrate which contained the guard cell protoplasts. Protoplasts were collected by centrifugation at 150 g for 5 min and carefully layered on top of the same volume of Histopaque (−1077, Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA), followed by centrifugation at 150 g for 15 min. Intact GCPs retained between the two phases were collected using a transfer pipette and washed thoroughly with basic solution. The protoplasts were finally resuspended in 5 mL of basic solution. The yield of protoplasts was estimated with a hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, USA).

Guard cell protoplasts were allowed to recover under room light (8 ± 1 µmol·m−2·sec−1) at room temperature (~21 °C) for 1 h, then aliquots (1 mL) of guard cell protoplasts (approximately 0.8–1.2 million protoplasts, varying among replicates) were treated with 1 µL ABA (10 mM stock, final concentration 10 µM ABA; A.G. Scientific Inc., USA) for 0 (no ABA), 2, 15, or 60 min, respectively. Guard cell protoplasts treated with ethanol (solvent control) for 15 min were also prepared. At the end of the treatment, guard cell protoplasts were collected by centrifugation at 150 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Each guard cell protoplast pellet was frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for future analysis.

Stomatal bioassays in B. napus and FDA staining for monitoring of protoplast diameter

Leaf pieces or abaxial epidermal peels were prepared from fully expanded leaves excised before onset of the light period in the growth chamber, and then incubated with opening solution (5 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES-KOH, pH 6.15) for 3 h under light (intensity of 150 ± 25 µmol m−2 s−1) to promote stomatal opening. ABA or the solvent control (ethanol) was then added to the solution at a final concentration of 10 µM or 0.1% (v/v) respectively. At the indicated time points, leaf pieces or epidermal peels were observed under light microscopy (Carl Zeiss Inc., USA). Stomatal apertures were measured by analysis of the digital images using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times with 105 ± 5 stomata measured for each sample.

To measure protoplast diameters, guard cell protoplasting and ABA treatment were carried out as described above, then guard cell protoplasts were collected by centrifugation and FDA (final concentration 5 µM) was added for ~1 min to allow the dye to permeate through cell membranes. FDA was excited by the 488 nm line of the argon laser and detected using a bandpass emission filter (500–550 nm) and images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510, Carl Zeiss Inc., USA). Diameters were measured by analysis of the digital images using ZEN (version 2012, Carl Zeiss Inc., USA). Each experiment was repeated three times with 105 ± 5 GCPs measured for each sample.

Sample preparation and GC-MS/MS analysis

Before derivatization, pellets from 4–6 individual protoplastings were pooled to compose one biological replicate, which contained 4–4.5 million GCPs. Five replicates were prepared for GC-MS analysis. For GC-MS analysis, metabolite extraction and derivatization were conducted simultaneously through the derivation procedure. Briefly, 10 µL of methoxamine (MOX) reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) was added to each biological replicate and incubated at 28 °C for 90 min. Then 90 µL of N, O-bistrifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) + 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) was added to each sample, followed by shaking at 400 rpm at 60 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation for 15 min at 12000 rpm, the supernatant of each sample was transferred to a glass auto-sample vial. Samples were then injected in a randomized order, with 0.5 µL of each sample injected into an Agilent 7980 A/5975 C GC-MS (Agilent Technologies, USA) with a 37.5 min temperature gradient: 50 °C for 1 min then ramping to 315 °C at 10 °C/min followed by 315 °C for 10 min.

Data analysis for GC-MS/MS datasets

For analysis of GC-MS data, peaks of each sample were detected and deconvoluted using Automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System (AMDIS, National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA) with the following settings: Component width - 20; Adjacent peak subtraction - One; Resolution - High; Sensitivity - Medium; Shape requirement - Medium. Peak alignment across samples and feature identification were completed using Mass Profile Professional (MPP) software (Agilent Technologies, USA) with the following parameters: minimal ion number 4; mass tolerance 0.1 Da; retention time tolerance 0.3 min; appearance filter - 60% within one sample group. Spectra of all aligned peaks were searched against the NIST 11 mass spectral library (National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA) using the built-in ID Browser function in MPP. Metabolites with a score over 70 were considered as confident identification based on previous publications97. Peak areas were exported and normalized against input GCP number and were log2 transformed for statistical analysis. A p value ≤ 0.05 (Student’s t test) together with at least 20% change in abundance based on peak area were used as criteria to define metabolic features with significant changes between samples.

Sample preparation and LC-MS/MS analysis

Before metabolite extraction, pellets from 4–6 individual protoplastings were pooled to compose one biological replicate, which contained 4–4.5 million GCPs. Five replicates were prepared for LC-MS/MS analysis. Metabolites were extracted by adding 50 µL of LC-MS injection solution (3% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, with chlorpropamide as internal standard) and vortexed for 1 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation for 15 min at 12000 rpm, the supernatant of each sample was transferred to an auto-sample vial. Samples were randomized and analyzed on an HPLC-QTOFMS (Shimadzu Prominence UFLC XR and AB Sciex 5600 quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry) platform. Five microliters of each sample was separated on an Acquity BEH C18 Column (100 × 2.1 mm 1.7 µm, Waters, USA) using a gradient with aqueous acetonitrile ramping from 3% to 90% in the mobile phase at a flow rate of 250 µL/min. Both positive and negative ion electrospray ionization mass spectra were acquired over the mass range 50–1250 Da. Data acquisition was under information dependent acquisition (IDA) mode with one 100 ms survey scan and up to twenty 100 ms MS/MS product ion scans per duty cycle.

Data analysis for LC-MS/MS datasets

MS peaks from the LC-MS/MS datasets were extracted and aligned across all samples using MarkerViewTM software (AB Sciex Pte Ltd., USA) with the following parameters: retention times between 0 min and 20.00 min.; Subtraction Offset of 10 scans; Subtraction Mult. Factor of 1.3; Noise Threshold of 50; Min. Spectral Peak Width of 15 ppm; Min. RT Peak Width of 5 scans; Retention Time Tolerance of 0.25 min.; Mass Tolerance of 25.0 ppm; Maximum of 100,000 peaks98. These parameters were optimized using the Check Peak Alignment function of MarkerViewTM.

For metabolome profiling (0 time point), presence of a MS peak in at least 4 out of 5 replicates was required for export of MS/MS data for metabolite identification. For ABA responsive feature identification, presence of a MS peak in at least 3 samples out of 25 samples (5 treatments with 5 replicates for each treatment) was first required, next, whether peak area was significantly changed by ABA treatment was assessed, and finally, for those showing significant changes, MS/MS data were exported for metabolite identification. Principal component analysis was performed with all detected features from the three analysis methods using MarkerViewTM with base-e logarithm of the peak areas as weighing option and Pareto as scaling option.

Peaks annotated as monoisotopic ions with an m/z between 100 and 800 and a retention time between 1.5 and 16 minutes were exported for further analysis. After normalization against the chlorpropamide peak area (internal standard), peak areas were log2 transformed for statistical analysis between sample groups. A p value ≤0.05 (Student’s t test) together with at least 20% change in normalized MS peak area were used as criteria to define metabolic features with significant changes between samples38,39. MS/MS spectra of peaks present in at least four replicates of 0 min (control) sample and those peaks showing significant changes upon ABA treatment were exported from PeakViewTM software (AB Sciex Pte Ltd., USA). Raw spectral intensity was converted to relative peak intensity ranging from 0–999 using Excel for each peak and submitted to MassBank (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan) for identification. A similarity score for each hit is calculated by the MassBank search according to the method of Horai et al.61. We consider a hit with score greater than 0.6 as identified at identification level 261,99; we report the metabolite with the highest score for each inquiry spectrum. Exogenous compounds such as drugs, herbicides, pesticides, and non-plant derived metabolites were manually excluded99. A general consensus has been reached for four levels of metabolite identification: 1) identified compounds, i.e., definitive identification; 2) putatively annotated compounds; 3) putatively characterized compound classes; and 4) unknown compounds99,100. It is proposed that definitive identification requires comparison of a minimum of two independent properties (e.g., retention time and mass spectrum, accurate mass and tandem MS) to an authentic compound standard analyzed on the same instrument and under identical conditions. Comparison to values reported for authentic compounds based on the literature or external laboratory data results in level 2 identifications99. The metabolites reported in our study meet the standards for this second level for identification.

Metabolite mapping and pathway enrichment analysis

Of the 390 metabolites we identified, there were 286 metabolites with a KEGG compound index. The list of KEGG compound indices was submitted to KEGG for mapping against B. napus and B. rapa as reference organsims using the User Data Mapping function (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?map01100). Mapped metabolites are indicated with black circles in the metabolic pathway overview (Supplemental Fig. S1) and are annotated as mapped in Supplemental Table 1. The compounds listed in PMN for B. rapa (Chinese cabbage) were downloaded from PMN (http://www.plantcyc.org/). The metabolites we identified were checked manually for presence in the PMN B. rapa compound list (Supplemental Table 1).

A pathway enrichment analysis was performed using all available KEGG IDs of the ABA responsive metabolites (a total of 58) against the KEGG A. thaliana reference metabolome (with 87 pathways) using MetaboAnalyst 3.040. The hypergeometric test was used for over-representation analysis and relative-betweeness centrality was used for pathway topology analysis39. Results (Supplemental Table 3) were generated through MetaboAnalyst.

Stomatal bioassays in A. thaliana and B. napus

The effects of quercetin, sinigrin, sitosterol, and campesterol were investigated in A. thaliana and B. napus grown under the same conditions as described above for B. napus GCP isolation. Fully expanded leaves from ~5 week old A. thaliana or ~6 week old B. napus leaf pieces (~5 mm × 5 mm) were excised before onset of the light period in the growth chamber, and then incubated with opening solution (5 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES-KOH, pH 6.15) for 2.5 h under white light (intensity of 150 ± 25 µmol m−2 s−1) to promote stomatal opening. Treatments were added as follows: ethanol as solvent control, 50 µM ABA with or without 1 µM quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA), 10 µM ABA with or without 50 µM sinigrin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA), 10 µM ABA with or without 5 µM sitosterol (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., USA), or 10 µM ABA with or without 2 µM campesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., USA). B. napus leaf pieces or A. thaliana abaxial epidermes peeled at indicated time points were used for stomatal image acquisition under a light microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., USA) connected to a digital camera (Nikon Inc., USA). Stomatal apertures were measured by analysis of the digital images using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). Each experiment was repeated at least three times with 105 ± 5 stomata measured per sample. Treatments were blinded during image acquisition and analysis.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation grants IOS 1025837 and MCB-1157921 to S.M.A. We thank Dr. Philip B. Smith at the Metabolomics Core Facility, Pennsylvania State University for technical assistance during data acquisition and analysis. The facility equipment AB Sciex 5600 quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry was purchased with financial support from NSF-MRI award CBET-1126373. Dr. Byeong Wook Jeon is acknowledged for providing the image in Fig. 1B. Drs Sixue Chen, Biswapriya B. Misra, and David Granot are acknowledged for helpful discussion during manuscript preparation.

Author Contributions

S.M.A. and M.Z. designed experiments, M.Z. performed experiments and analyzed data, S.M.A. and M.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13166-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Taiz, L. & Zeiger, E. Plant Physiology. 756–757 (Sinauer Associates, Inc., 2010).

- 2.Collins NC, Tardieu F, Tuberosa R. Quantitative trait loci and crop performance under abiotic stress: where do we stand? Plant Physiol. 2008;147:469–486. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubbard KE, Nishimura N, Hitomi K, Getzoff ED, Schroeder JI. Early abscisic acid signal transduction mechanisms: newly discovered components and newly emerging questions. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1695–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1953910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umezawa T, et al. Molecular basis of the core regulatory network in ABA responses: sensing, signaling and transport. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1821–1839. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi-Saha A, Valon C, Leung J. A brand new START: abscisic acid perception and transduction in the guard cell. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SC, Luan S. ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murata Y, Mori IC, Munemasa S. Diverse stomatal signaling and the signal integration mechanism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:369–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonhardt N, et al. Microarray expression analyses of Arabidopsis guard cells and isolation of a recessive abscisic acid hypersensitive protein phosphatase 2C mutant. Plant Cell. 2004;16:596–615. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Assmann SM, Albert R. Predicting essential components of signal transduction networks: a dynamic model of guard cell abscisic acid signaling. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:e312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu M, Simons B, Zhu N, Oppenheimer DG, Chen S. Analysis of abscisic acid responsive proteins in Brassica napus guard cells by multiplexed isobaric tagging. J. Proteomics. 2010;73:790–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang RS, et al. Common and unique elements of the ABA-regulated transcriptome of Arabidopsis guard cells. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin X, et al. Abscisic acid-responsive guard cell metabolomes of Arabidopsis wild-type andgpa1 G-protein mutants. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4789–4811. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.119800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Z, Jin X, Albert R, Assmann SM. Multi-level modeling of light-induced stomatal opening offers new insights into its regulation by drought. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu M, et al. Thiol‐based redox proteins in abscisic acid and methyl jasmonate signaling in Brassica napus guard cells. Plant J. 2014;78:491–515. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munemasa S, et al. Mechanisms of abscisic acid-mediated control of stomatal aperture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;28:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinaki J, Heravan EM, Rad AS, Noormohammadi G, Zarei G. The effects of water deficit during growth stages of canola (Brassica napus L.) Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2007;2:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu M, Dai S, McClung S, Yan X, Chen S. Functional differentiation of Brassica napus guard cells and mesophyll cells revealed by comparative proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:752–766. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800343-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misra BB, Acharya BR, Granot D, Assmann SM, Chen S. The guard cell metabolome: functions in stomatal movement and global food security. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:334. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, M. et al. Preparation of epidermal peels and guard cell protoplasts for cellular, electrophysiological, and –omics assays of guard cell function. In Plant Signal Transduction Methods and Protocols (ed. Botella, M. A. & Botella, J.) 1363, 89–121 (Springer, 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubakhin SS, Lanni EJ, Sweedler JV. Progress toward single cell metabolomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013;24:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misra BB, Assmann SM, Chen S. Plant single-cell and single-cell-type metabolomics. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattanzio V, Kroon PA, Quideau S, Treutter D. Plant phenolics-secondary metabolites with diverse functions. Recent Advances in Polyphenol Research. 2008;1:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodacre R, Vaidyanathan S, Dunn WB, Harrigan GG, Kell DB. Metabolomics by numbers: acquiring and understanding global metabolite data. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misra BB, de Armas E, Tong Z, Chen S. Metabolomic responses of guard cells and mesophyll cells to bicarbonate. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng S, et al. Jasmonate-mediated stomatal closure under elevated CO2 revealed by time-resolved metabolomics. Plant J. 2016;88:947–962. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornish K, Zeevaart JA. Abscisic acid accumulation by roots of Xanthium strumarium L. and Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. in relation to water stress. Plant Physiol. 1985;79:653–658. doi: 10.1104/pp.79.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies WJ, Zhang J. Root signals and the regulation of growth and development of plants in drying soil. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1991;42:55–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.000415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Mata C, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide and abscisic acid cross talk in guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:790–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.011020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwai S, Shimomura N, Nakashima A, Etoh T. New fava bean guard cell signaling mutant impaired in ABA-induced stomatal closure. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:909–913. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodd IC. Abscisic acid and stomatal closure: a hydraulic conductance conundrum? New Phytol. 2013;197:6–8. doi: 10.1111/nph.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daloso DM, et al. Tobacco guard cells fix CO2 by both RubisCO and PEPcase whilst sucrose acts as a substrate during light induced stomatal opening. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:2353–2371. doi: 10.1111/pce.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.t’Kindt R, Morreel K, Deforce D, Boerjan W, Van Bocxlaer J. Joint GC-MS and LC-MS platforms for comprehensive plant metabolomics: Repeatability and sample pre-treatment. J. Chromatogr. B. 2009;877:3572–3580. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osorio S, Do PT, Fernie AR. Profiling primary metabolites of tomato fruit with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;860:101–109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-594-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee DK, et al. Comparison of primary and secondary metabolites for suitability to discriminate the origins of Schisandra chinensis by GC/MS and LC/MS. Food Chem. 2013;141:3931–3937. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yonekura-Sakakibara K, et al. Comprehensive flavonol profiling and transcriptome coexpression analysis leading to decoding gene-metabolite correlations in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2008;20:2160–2176. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreher K. Putting the plant metabolic network pathway databases to work: going offline to gain new capabilities. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1083:151–171. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-661-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misra BB, de Armas E, Chen S. Differential metabolomic responses of PAMP-triggered immunity and effector-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Metabolomics. 2016;12:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11306-016-0984-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostafa I, et al. New nodes and edges in the glucosinolate molecular network revealed by proteomics and metabolomics of Arabidopsis myb28/29 and cyp79B2/B3 glucosinolate mutants. J. Proteomics. 2016;138:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0-making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–W257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia J, Wishart DS. MetPA: a web-based metabolomics tool for pathway analysis and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2342–2344. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreyra MLF, Rius SP, Casati P. Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions, and biotechnological applications. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:222. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingale AG, Hivrale AU. Pharmacological studies of Passiflora sp. and their bioactive compounds. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2010;4:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwak JM, et al. NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS‐dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2003;22:2623–2633. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song Y, Miao Y, Song CP. Behind the scenes: the roles of reactive oxygen species in guard cells. New Phytol. 2014;201:1121–1140. doi: 10.1111/nph.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakabayashi R, et al. Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 2014;77:367–379. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watkins JM, Hechler PJ, Muday GK. Ethylene-induced flavonol accumulation in guard cells suppresses reactive oxygen species and moderates stomatal aperture. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:1707–1717. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witkowski E, Lamont BB. Leaf specific mass confounds leaf density and thickness. Oecologia. 1991;88:486–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00317710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan X, Chen S. Regulation of plant glucosinolate metabolism. Planta. 2007;226:1343–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Z, Zhang W, Stanley BA, Assmann SM. Functional proteomics of Arabidopsis thaliana guard cells uncovers new stomatal signaling pathways. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3210–3226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Islam MM, et al. Myrosinases, TGG1 and TGG2, redundantly function in ABA and MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1171–1175. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khokon M, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) induces stomatal closure in. Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:1900–1906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reichelt M, et al. Benzoic acid glucosinolate esters and other glucosinolates from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2002;59:663–671. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andersson D, et al. Myrosinases from root and leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana have different catalytic properties. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brechenmacher L, et al. Soybean metabolites regulated in root hairs in response to the symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Plant Physiol. 2007;153:1808–1822. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fraser PD, Enfissi E, Goodfellow M, Eguchi T, Bramley PM. Metabolite profiling of plant carotenoids using the matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization time‐of‐flight mass spectrometry. Plant J. 2007;49:552–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salek RM, Steinbeck C, Viant MR, Goodacre R, Dunn WB. The role of reporting standards for metabolite annotation and identification in metabolomic studies. Gigascience. 2013;2:13. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown M, et al. Automated workflows for accurate mass-based putative metabolite identification in LC/MS-derived metabolomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1108–1112. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oberacher H. Applying tandem mass spectral libraries for solving the critical assessment of small molecule identification (CASMI) LC/MS challenge 2012. Metabolites. 2013;3:312–324. doi: 10.3390/metabo3020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schymanski EL, Gerlich M, Ruttkies C, Neumann S. Solving CASMI 2013 with MetFrag, MetFusion and MOLGEN-MS/MS. Mass Spectrom. 2014;3:S0036. doi: 10.5702/massspectrometry.S0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horai H, et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:703–714. doi: 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lawson T. Guard cell photosynthesis and stomatal function. New Phytol. 2009;181:13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimazaki KI, Gotow K, Sakaki T, Kondo N. High respiratory activity of guard cell protoplasts from Vicia faba L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1983;24:1049–1056. [Google Scholar]