Abstract

Purpose

Positron emission tomography (PET) ligands targeting translocator protein (TSPO) are potential imaging diagnostics of cancer. In this study, we report two novel, high-affinity TSPO PET ligands that are 5,7 regioisomers, [18F]VUIIS1009A ([18F]3A) and [18F]VUIIS1009B ([18F]3B), and their initial in vitro and in vivo evaluation in healthy mice and glioma-bearing rats.

Procedures

VUIIS1009A/B was synthesized and confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Interactions between TSPO binding pocket and novel ligands were evaluated and compared with contemporary TSPO ligands using 2D 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectroscopy. In vivo biodistribution of [18F]VUIIS1009A and [18F]VUIIS1009B was carried out in healthy mice with and without radioligand displacement. Dynamic PET imaging data were acquired simultaneously with [18F]VUIIS1009A/B injections in glioma-bearing rats, with binding reversibility and specificity evaluated by radioligand displacement. In vivo radiometabolite analysis was performed using radio-TLC, and quantitative analysis of PET data was performed using metabolite-corrected arterial input functions. Imaging was validated with histology and immunohistochemistry.

Results

Both VUIIS1009A (3A) and VUIIS1009B (3B) were found to exhibit exceptional binding affinity to TSPO, with observed IC50 values against PK11195 approximately 500-fold lower than DPA-714. However, HSQC NMR suggested that VUIIS1009A and VUIIS1009B share a common binding pocket within mammalian TSPO (mTSPO) as DPA-714 and to a lesser extent, PK11195. [18F]VUIIS1009A ([18F]3A) and [18F]VUIIS1009B ([18F]3B) exhibited similar biodistribution in healthy mice. In rats bearing C6 gliomas, both [18F]VUIIS1009A and [18F]VUIIS1009B exhibited greater binding potential (k3/k4) in tumor tissue compared to [18F]DPA-714. Interestingly, [18F]VUIIS1009B exhibited significantly greater tumor uptake (VT) than [18F]VUIIS1009A, which was attributed primarily to greater plasma-to-tumor extraction efficiency.

Conclusions

The novel PET ligand [18F]VUIIS1009B exhibits promising characteristics for imaging glioma; its superiority over [18F]VUIIS1009A, a regioisomer, appears to be primarily due to improved plasma extraction efficiency. Continued evaluation of [18F]VUIIS1009B as a high-affinity TSPO PET ligand for precision medicine appears warranted.

Keywords: PET, VUIIS1009A, VUIIS1009B, TSPO, Cancer imaging, Precision medicine

Introduction

Alterations in cellular metabolism represent a distinguishing and actionable feature of cancer cells, in contrast to surrounding, otherwise healthy, tissues. While many tumors exhibit elevated metabolism of glucose and glutamine [1–4], elevated cholesterol metabolism is also a characteristic of many human tumors [5, 6]. Translocator protein (TSPO) is an 18-kDa protein, primarily localized to mitochondria, that facilitates cholesterol transport and metabolism. TSPO is highly expressed in numerous solid tumors, including those of the central nervous system [7, 8], oral cavity [9], liver [10, 11], breast [12, 13], and colon [14–16], where elevated levels tend to be associated with poor outcome. These findings support TSPO as a potentially important biomarker in oncology and suggest the utility of tumor-selective TSPO ligands for cancer imaging with positron emission tomography (PET).

In prior studies, we have shown that high-affinity, pyrazolopyrimidine TSPO PET probes such as [18F]DPA-714 (1) [17] and [18F]VUIIS1008 (2) [18, 19], as well as contemporary TSPO ligands based upon other unique scaffolds [20–22], can be used to visualize TSPO expression in tumors in preclinical settings (Fig. 1). The novel ligand [18F]VUIIS1008, a 5,7-diethyl analog of [18F]DPA-714, was developed through focused library synthesis and structure-activity relationship (SAR) development of the 5,6,7-substituted pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold of 1. [18F]VUIIS1008 proved to be a highly potent TSPO PET ligand, exhibiting a 36-fold enhancement in TSPO affinity, compared to 1, and high radiochemical yield and specific activity.

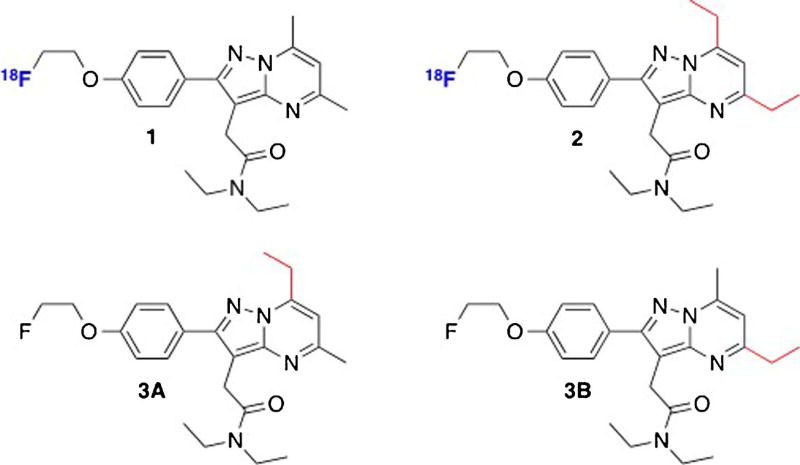

Fig. 1.

Pyrazolopyrimidine TSPO ligands: 1, [18F]DPA-714; 2, [18F]VUIIS1008; 3A, VUIIS1009A; 3B, VUIIS1009B.

More recently, further refinement of the SAR inherent to the pyrazolopyrimidine core led us to the new compounds reported here, N,N-diethyl-2-(7-ethyl-2-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)-phenyl)-5-methylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)acetamide (VUIIS1009A (3A)) and N,N-diethyl-2-(5-ethyl-2-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-7-methylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)acetamide (VUIIS1009B (3B)) (Fig. 1). Both compounds share the common pyrazolopyrimidinal core with 1 and 2 but are unique 5- and 7-regioisomers bearing pendant methyl or ethyl moieties. These seemingly minor structural variations led to exceptional (picomolar) TSPO binding affinities for 3A and 3B, which were 20-fold greater than 2 and 500-fold that of 1, prompting our subsequent further characterization of these ligands.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Preparation and Characterization

[3H]PK11195 was purchased from PerkinElmer. Phosphate-buffered saline and CytoScint ES Liquid Scintillation Cocktail were purchased from MP Biomedicals. 2,4-Hexanedione was purchased from Accel Pharmtech, USA. All other synthesis reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received, unless noted otherwise. Ligands 3A and 3B and radioligand precursors (6A, 6B) were prepared (Supplemental Fig. 1). Compound characterization was performed using 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and X-ray diffraction on select compounds (see Supplemental Information).

In Vitro Binding Assay

Ligand binding experiments were conducted in C6 glioma cell lysates as previously described [17, 18], using 3A and 3B as the cold ligands. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

NMR Titration

15N-labeled mitochondrial TSPO (mTSPO) was expressed in BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli in M9 minimal media, solubilized, and purified with dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) detergent, as adapted from previous publications [23, 24]. 2D 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of mTSPO with/without ligands (5.0 mM) were recorded on an 800-MHz NMR spectrometer at 42 °C with 0.2-mM TSPO in ∼2 % DPC (w/v), 25-mM MES buffer, pH 6.0, and 100 mM NaCl. Ligands tested were 1, 3A, 3B, and PK11195. Spectra were processed with NMRPipe and analyzed using Sparky.

Animals

All studies involving mice and rats were conducted in compliance with federal and institutional guidelines. C57BL/6 male mice (∼25 g) were used for healthy biodistribution studies. For glioma model studies, healthy male Wistar rats (∼280 g) were stereotactically inoculated in the right hemisphere with 1.0 × 105 C6 glioma cells (American Type Culture Collection; Manassas, VA, USA) using a Hamilton syringe in a stereotactic apparatus (Stoelting) 2 weeks prior to imaging. Coordinates used for cell injection were 4 mm lateral to the bregma and 5 mm in depth to the dural surface. Rats were then affixed with venous and arterial catheters prior to the MRI and PET/CT studies.

Radioligand Preparation

[18F]3A and [18F]3B were prepared analogously to methods published in previous studies [17–19] (see Supplemental Information).

MRI, PET, and CT Imaging

MRI was used to localize all C6 tumors using previously published method [17]. PET/CT was initiated within 24 h of MRI in rats with confirmed tumors (n = 31). Each rat was imaged with [18F]3A followed by [18F]3B 24 h later, or vice versa, in a randomized fashion. Tumor-bearing rats were administered 1.35 ± 0.22 mCi (50.00 ± 8.07 MBq) [18F]3A (n = 17) or 1.30 ± 0.30 mCi (48.14 ± 11.38 MBq) of [18F]3B (n = 14) via a jugular catheter while in a microPET Focus 220 scanner (Siemens). Data were collected in list-mode format for 60 min, followed by a CT scan (MicroCAT II; Siemens) for attenuation correction. For displacement studies of [18F]3A (n = 3) and [18F]3B (n = 3), 3A and 3B (10 mg/kg), respectively, were injected at 30 min via a catheter. During the scans, blood samples were drawn according to the following schedule: 15 µl every 10 s for the first 90 s and at 5, 8, 20, and 45 min while 200 µl were drawn at 2, 12, 30, and 60 min for metabolite corrections. The dynamic PET acquisition was divided into twelve 10-s frames for the first 2 min, three 60-s frames for the following 3 min, and seventeen 300-s frames for the duration of the scan. The raw data within each frame were then binned into 3D sinograms, with a span of 3 and ring difference of 47. The sinograms were reconstructed into tomographic images (128 × 128 × 95) with voxel sizes of 0.095 × 0.095 × 0.08 cm3.

In Vivo Uptake and Displacement in Healthy Mice

For PET imaging, C57BL/6 male mice were administered 0.29 ± 0.02 mCi (10.75 ± 0.70 MBq) of [18F]3A (n = 6) or 0.31 ± 0.03 mCi (11.39 ± 1.26 MBq) of [18F]3B (n = 6) upon initiation of a dynamic PET acquisition. For displacement studies, 30 min following tracer infusion, non-radioactive 3A (10 mg/kg) or 3B (10 mg/kg) was administered by retro-orbital injection.

TLC Radiometabolite Analysis

Plasma radiometabolites of [18F]3A and [18F]3B were evaluated using radio-thin-layer chromatography (radio-TLC) according to the published methods [19].

Histology

Whole brains were harvested and fixed in 4 % buffered formalin for 48 h, followed by paraffin embedding for histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Tissue sections (5.0 µm) were stained with TSPO-specific rabbit polyclonal anti-rat/anti-mouse antibody (Novus Biologicals, LLC; Littleton, CO). Immunoreactivity was assessed using a horseradish peroxidase detection kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used to evaluate cell density and tumor localization. Sections were visualized and documented using bright field microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Inc.; Buffalo Grove, IL).

Image Analysis and Modeling

For PET imaging of glioma-bearing rats, time-activity curves (TACs) were generated by manually drawing 3D volumes of interest over tumor and contralateral brain using ASIPro (Siemens). The arterial input function (AIF) was computed from plasma sampling manually (15 µl) during imaging and corrected for metabolism of the parent ligand. In this study, a two-tissue, four-rate-constant kinetic model was explored with the PMOD software package as metrics to reflect [18F]3A/B pharmacokinetics in reference tissues, such as tumor and brain. Model fit was evaluated by chi-squared (χ2) values and visual inspection. For PET imaging of mice, ROIs corresponding to heart, lung, kidney, and liver were manually drawn using ASIPro. We applied two approaches to calculate the total distribution volume (VT) of the radiotracer, including the Logan plot analysis [25] and the kinetic analysis using a two-tissue compartment model [26]. The metabolite-corrected plasma curve was used as an input function in a plasma plus two-tissue compartment model.

Biodistribution

Biodistribution of [18F]3A/B was characterized in healthy C57BL/6 male mice. Calculation of %ID/cc for a variety of tissues was based on the cut-and-count results 60 min after probe injection. In order to characterize binding specificity in healthy tissues, we also evaluated biodistribution in a displacement assay, administering non-radioactive 3A or 3B (10 mg/kg) 30 min after corresponding radioligand injection. Tissue %ID/cc was calculated based on cut-and-count results 60 min post probe injection. The target tissues were then resected and weighed, followed by radioactivity measurement in a well counter (Capintec; NJ).

Plasma Protein Binding

The degree of compound bound to plasma protein was determined with the equilibrium dialysis method [27] at the Vanderbilt High-Throughput Screening Core Facility. Detailed method is included in Supplemental Information.

Results

Chemical Synthesis of 3A and 3B and Radiofluorination Precursors 6A and 6B

Synthesis of 3A and 3B began with condensation of the pyrazole core of 4 with 2,4-hexanedione (Supplemental Fig. 1). Subsequent acid cleavage of the methoxy groups yielded intermediates 5A and 5B, which were resolved using HPLC and crystallized for structure determination via X-ray crystallography (Fig. 2). The X-ray structure of compound 5A displayed the 5-methyl and 7-ethyl substitution patterns on the pyrazolopyrimidinal ring, while compound 5B displayed the reverse, 5-ethyl and 7-methyl. Reaction of 5A and 5B with tosylated fluoroethanol under microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) conditions [17–19] gave compounds 3A and 3B, respectively (Fig. 1). The corresponding radiochemistry precursors 6A and 6B were synthesized in analogous fashion, with 5A and 5B coupled to di-tosylated glycol using MAOS. For subsequent in vitro assay testing, 3A and 3B served as the corresponding non-radioactive (fluorine-19) analogs.

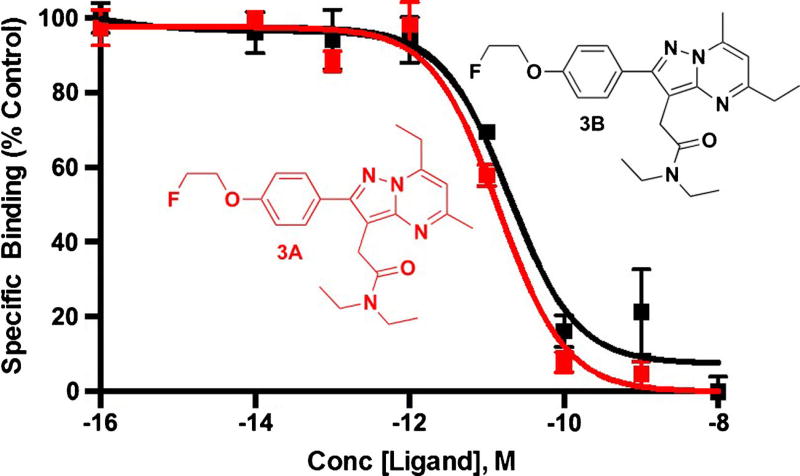

Fig. 2.

Radioligand displacement of [3H]PK11195 with 3A (KI = 7.04 pM) and 3B (KI = 9.47 pM) in C6 glioma cell lysate. Kd = 5.73 ± 2.38 nM for C6-2B mitochondria (rat glioma) [28] with [3H]PK11195. 3A (IC50 = 14.4 pM) and 3B (IC50 = 19.4 pM) in C6 glioma cell lysate. IC50 inhibitory concentration of 50 %, Conc concentration.

Specific Binding of 3A and 3B to TSPO in Cell Line Homogenates

To evaluate TSPO binding of 3A and 3B in vitro, radioligand displacement was performed in C6 glioma cell lysate using [3H]PK11195 [17, 22], with affinities expressed as IC50 (nM) (Fig. 2). Both 3A and 3B competitively displaced [3H]PK11195 to near-background levels in a dose-dependent manner. Non-linear regression analysis of the binding data yielded IC50 values of 14.4 pM for 3A and 19.4 pM for 3B, both superior to the previously reported VUIIS1008 (0.3 nM) [18, 19] and DPA-714 (10.9 nM) [17, 18].

Protein Binding Pockets for 3A and 3B in Mammalian TSPO

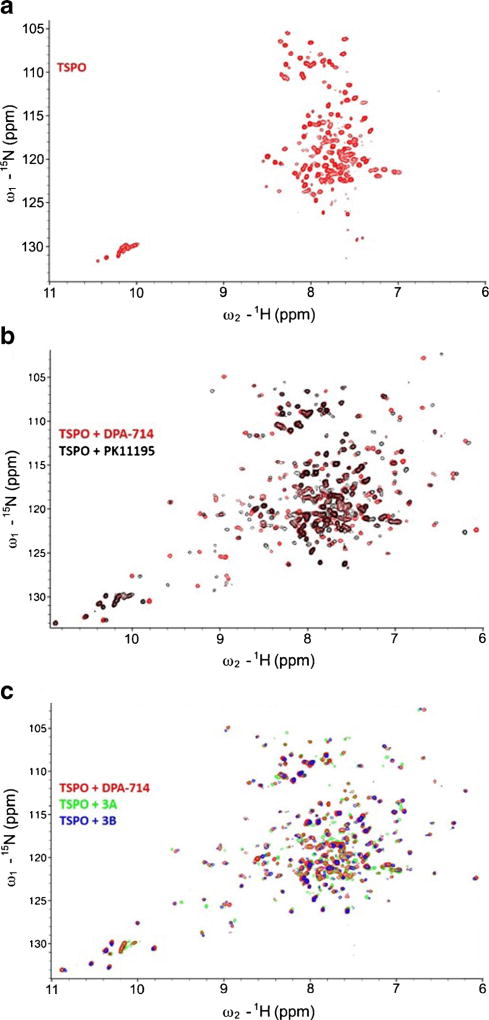

Jaremko et al. recently reported that the structure of TSPO could be stabilized in the presence of PK11195, yielding a tight bundle of five transmembrane α helices that forms a hydrophobic binding pocket to accept PK11195. 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR analysis of this structure allowed for a high-quality spectrum of the ligand-bound state of the protein [23]. To investigate the differences in the structure of TSPO when bound to 3A and 3B, 2D HSQC spectroscopy was used to observe structural features of each ligand-bound state of the protein and compared to DPA-714 and PK11195. In a 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum, peaks arise from amides in the protein backbone and side chains, which are highly dependent on the chemical environment surrounding each amide group. This allows the HSQC spectrum to serve as a solution-phase fingerprinting method of protein structure.

The ligand-free TSPO reconstituted in DPC micelles displayed the same narrow dispersed spectrum as previously reported (Fig. 3a). Addition of PK11195 (Fig. 3b), as well as DPA-714 (Fig. 3c), resulted in highly dispersed spectra, with a new set of peaks representing signals from the ligand-bound state of the protein. The DPA-714 spectrum showed significant differences in chemical shift perturbation when compared with the PK11195 spectrum (Fig. 3b), which are possibly due to the different chemical groups from the two compounds interacting with the protein, the different ligand-induced protein conformational changes, and the ligand-binding pocket formed for DPA-714 being different from that of PK11195. Titrating 3A or 3B into the TSPO also gave improved spectral dispersion, though in our hands, of the four compounds tested, only 3B completely saturated the ligand-bound state. No obvious changes in chemical shift perturbation were observed between DPA-714, 3A, or 3B (Fig. 3c), indicating that all three ligands bind the same site within the TSPO binding pocket and elicit similar ligand-induced conformational changes within the protein.

Fig. 3.

2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of TSPO in presence of different ligands. a The 2D HSQC spectrum of TSPO in the absence of ligand. b Comparison of TSPO spectra in presence of 5.0-mM PK11195 (black) and 5.0-mM DPA-714 (red). c Comparison of TSPO spectra in presence of 5.0-mM DPA-714 (red), 5.0-mM 3A (green), and 5.0-mM 3B (blue) (color figure online).

Radiosynthesis of [18F]3A and [18F]3B

To produce [18F]3A and [18F]3B, precursors 6A or 6B underwent nucleophilic fluorination with fluorine-18 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Purification of [18F]3A and [18F]3B was performed with preparative HPLC. The retention time of [18F]3A was 12 min according to gamma detection, which was in agreement with the UV retention time of 3A. Similarly, the retention time of [18F]3B and was 12 min according to gamma detection, which also corresponded to the UV retention time of 3B. Radiochemical purity was consistently greater than 99 %, with specific activity consistently greater than 4203 Ci/mmol (156 TBq/mmol) (n = 33).

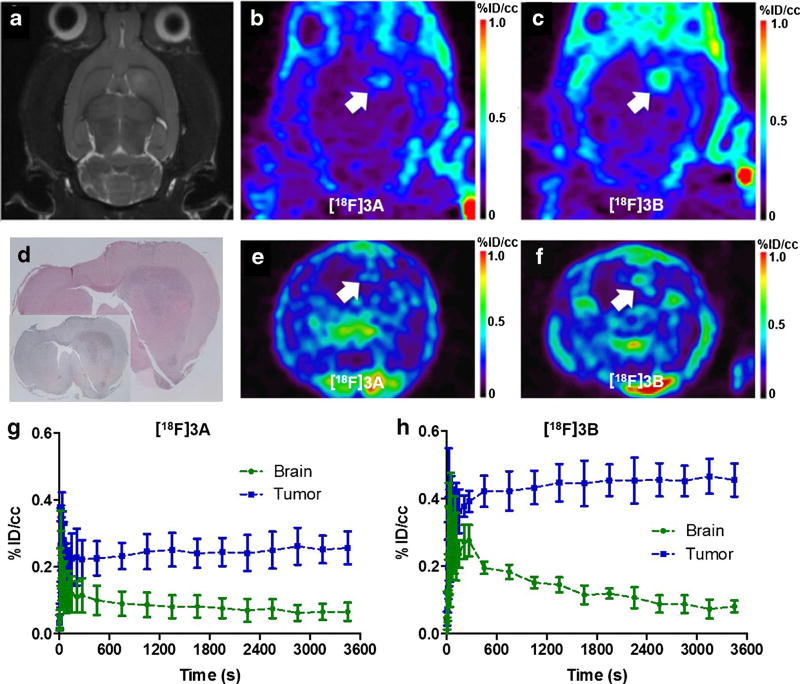

In Vivo PET Imaging of [18F]3A and [18F]3B in C6 Glioma

Uptake of both [18F]3A and [18F]3B was evaluated in a well-characterized rat model of glioma (C6) using dynamic PET imaging [17–19, 21, 22]. Preclinical gliomas were first localized using T2-weighted MRI, which exhibited the typical hyperintensity in the right hemisphere due to longer T2 relaxation times compared to surrounding normal brain tissue (Fig. 4a). Similar to the performance of 1 and 2, both [18F]3A and [18F]3B demonstrated high levels of uptake in tumor, with modest accumulation in normal tissue (Fig. 4b, c, e, f, Supplemental Fig. 2). For validation of PET, following sacrifice, imaging-matched brains were processed for H&E staining (Fig. 4d) and TSPO IHC (Fig. 4d, inset). Corresponding to tumors localized by H&E staining, we observed the typical elevation of TSPO immunoreactivity seen in this model compared with surrounding, non-tumor brain [17–19, 21, 22]. In addition, PET imaging with both [18F]3A (Fig. 4e) and [18F]3B (Fig. 4f) corresponded well with histology results.

Fig. 4.

Preclinical PET imaging with [18F]3A and [18F]3B in the same glioma-bearing rat. a T2-weighted MRI (coronal). b PET imaging with [18F]3A(coronal). c PET imaging of the glioma-bearing rats with [18F]3B (coronal). d H&E staining and TSPO immunohistological staining (inset) of the image-matched tissue. e PET imaging of the glioma-bearing rats with [18F]3A (transverse). f PET imaging of the glioma-bearing rats with [18F]3B (transverse). g TACs for brain and tumor in [18F]3A-imaged rats (n = 9). h TACs for brain and tumor in [18F]3B-imaged rats (n = 6). Tumor is marked with the white arrow.

Interestingly, when comparing the TACs of [18F]3A with [18F]3B, we observed an increased and sustained level of tumor uptake (blue line) for [18F]3B compared with [18F]3A (Fig. 4g, h), indicating that while both [18F]3A and [18F]3B were rapidly delivered to normal tissue (green line), [18F]3A was cleared from tumor and non-tumor brains more rapidly than [18F]3B (Fig. 4g, h). Analysis of the last 30 min of uptake (Fig. 4g, h) indicated a twofold higher %ID/cc for [18F]3B (n = 6) (Fig. 4h) than [18F]3A (n = 8) (Fig. 4g) (0.4 versus 0.2).

In Vivo Metabolism Analysis

Similar to our previous work [17], radio-HPLC was used to evaluate [18F]3A and [18F]3B metabolisms in plasma at multiple time points during the PET scan (2, 12, 30, 60 min). Radiometabolite analysis (Supplemental Fig. 3) demonstrated a high level of [18F]3A or [18F]3B within the first 2 min following tracer injection (89.16 versus 94.00 %, respectively), indicating minimal metabolism of either [18F]3A or [18F]3B within the first 2 min. In contrast, however, over the time frame from 2 to 60 min, the two traces exhibited different rates of in vivo metabolism. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 3, after 60 min, the [18F]3A parent constituted 64.83 % of the plasma radioactivity, while the [18F]3B parent contributed only 46.63 %.

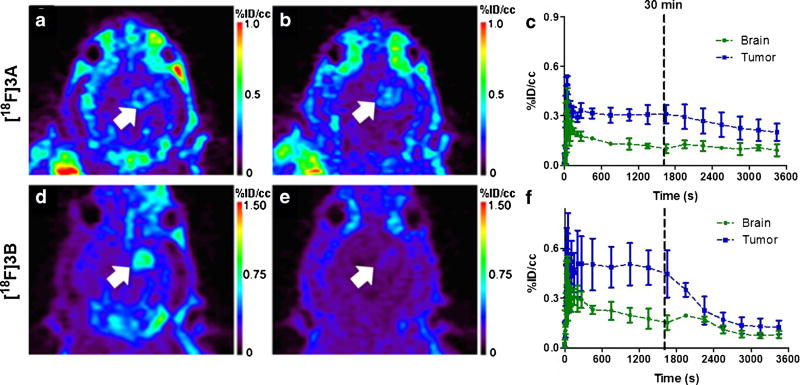

In Vivo Displacement of [18F]3A and [18F]3B

To evaluate the binding specificity of [18F]3A/B, displacement studies in C6 glioma-bearing rats were performed using 3A and 3B, respectively. During a typical 60-min dynamic PET study, an excess of 3A or 3B (10 mg/kg) was administrated intravenously 30 min after injection of the corresponding radioligand. Summation of the first 30 min of the dynamic scan demonstrated typical uptake characteristics for both [18F]3A (Fig. 5a and Supplemental Fig. 4a, c) and [18F]3B (Fig. 5b and Supplemental Fig. 4e, g). Summation of the final 30 min of the scan showed near-complete displacement for [18F]3B (Fig. 5e, Supplemental Fig. 4f, h), while only partial displacement for [18F]3A (Fig. 5b, Supplemental Fig. 4b, d). TAC analysis indicated 80 % displacement for [18F]3B (Fig. 5f), while only 33 % displacement for [18F]3A (Fig. 5c) at the end of the scan.

Fig. 5.

Displacement analysis for rats imaged by [18F]3A and [18F]3B with the injection of their corresponding cold analog (10 mg/kg) at 30 min. a Summation of the first 30 min PET imaging (coronal) with [18F]3A. b Summation of the last 30 min of PET imaging (coronal) with [18F]3A. c TACs for brain and tumor in [18F]3A displacement analysis. d Summation of the first 30 min of PET imaging (coronal) with [18F]3B (n = 3). e Summation of the last 30 min of PET imaging (coronal) with [18F]3B. f TACs for brain and tumor in [18F]3B displacement analysis (n = 3). Tumor is marked with the white arrow.

Pharmacokinetic Modeling of [18F]3A and [18F]3B

The pharmacokinetics of [18F]3A and [18F]3B uptake and clearance were modeled in tumor and normal brain. As with previous TSPO PET ligands evaluated in this setting [17, 22], [18F]3A and [18F]3B TACs for the tumor and normal brain fit a two-tissue, four-rate-constant kinetic model, as determined by inspection and chi-squared values. With the kinetic model (Supplemental Fig. 5a), quantitative analysis and pharmacokinetic parameter estimation were performed by fitting the TACs derived from the 60-min dynamic PET data (Supplemental Fig. 5b, c).

Based on this model, we estimated the values for the four kinetic parameters k1, k2, k3, and k4 (Table 1). Probe binding potential (BPND) was calculated as k3/k4, denoting the ratio at equilibrium of specifically bound radioligand to that of non-displaceable radioligand in tissue. This state of equilibrium is reached at approximately 40 min post radiotracer injection as evident by the plasma and tissue TACs (Supplemental Fig. 5). The BPND calculated in Table 1 indicates an approximately twofold higher tumor BPND for both [18F]3A (BPND = 16.170) and [18F]3B (BPND = 14.072) when compared with the lead, [18F]DPA-714 (BPND = 8.913) [17], indicating higher specific binding characteristics for these two ligands in tumor tissue. While [18F]3A and [18F]3B demonstrates similar BPND values in tumor, they did differ in normal brain. As Table 1 shows, the brain BPND for [18F]3A was 6.748 but only 2.432 for [18F]3B, indicating a higher binding potential for [18F]3A in normal brain.

Table 1.

Kinetic modeling results using a two-tissue, four-parameter model for both [18F]3A (n = 9) and [18F]3B (n = 6)

| Probe | Region | k1 | k2 | k3 | k4 | k1/k2 | k3/k4 | VTa | VT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18F]VUIIS1009A (n = 9) | Tumor | 2.462 ± 0.550 | 5.335 ± 0.973 | 0.565 ± 0.075 | 0.036 ± 0.004 | 0.550 ±0.113 | 16.170 ± 2.370 | 7.347 ± 1.261 | 7.890 ± 0.764 |

| Brain | 2.164 ±0.462 | 7.165 ±0.835 | 0.727 ± 0.161 | 0.103 ±0.016 | 0.277 ± 0.054 | 6.748 ± 0.746 | 1.971 ± 0.300 | 1.940 ± 0.279 | |

| [18F]VUIIS1009B (n = 6) | Tumor | 6.386 ± 1.098 | 2.361 ±0.617 | 0.232 ± 0.026 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 3.047 ± 0.439 | 14.072 ± 1.074 | 44.482 ± 8.265 | 46.679 ± 9.343 |

| Brain | 6.257 ± 1.134 | 3.100 ± 0.830 | 0.178 ±0.029 | 0.082 ± 0.015 | 2.363 ± 0.355 | 2.432 ± 0.600 | 3.526 ± 1.275 | 7.423 ± 0.931 | |

| [18F]VUIIS1008 (n = 5) | Tumor | 0.709 ± 0.306 | 0.442 ± 0.101 | 0.113 ±0.013 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 1.902 ± 0.816 | 12.634 ± 1.406 | 25.224 ± 10.035 | |

| Brain | 0.881 ±0.392 | 2.078 ± 1.666 | 0.172 ± 0.070 | 0.037 ± 0.004 | 0.855 ± 0.325 | 4.435 ± 1.387 | 4.210 ± 1.612 | ||

| [18F]DPA-714 (n = 11) | Tumor | 5.708 ± 0.916 | 1.060 ±0.174 | 0.098 ± 0.013 | 0.011 ±0.001 | 6.867 ± 1.226 | 8.913 ± 1.155 | 70.033 ± 14.729 | |

| Brain | 5.674 ± 0.852 | 2.141 ±0.540 | 0.070 ± 0.0132 | 0.023 ± 0.005 | 3.619 ±0.551 | 4.024 ± 0.842 | 15.963 ± 3.566 |

Data = mean ± SEM

VT total distribution volume from kinetic parameters

Total distribution volume obtained with Logan plot analysis

k1/k2 denotes the ratio of influx to efflux in the two-tissue, four-rate-constant kinetic model, reflecting the transport efficiency of the probe from the plasma to the reference tissue. Close comparison of these values from Table 1 reveals the higher transport efficiency of [18F]3B over [18F]3A for both tumor (3.047 versus 0.550) and brain (2.363 versus 0.277).

Logan plot analysis demonstrated a total distribution volume (VT) for [18F]3B that is six times higher in the tumor and nearly twice as high in the brain compared to [18F]3A (see Table 1). The difference in VT between the two radiotracers was also confirmed via compartment modeling as displayed in Table 1. Taken together, we not only obtain higher uptake of [18F]3B in tumor compared to [18F]3A but also higher contrast-to-background ratio; tumor-to-normal brain = 12.7 ± 5.3 for [18F]3B and 3.7 ± 0.9 for [18F]3A (see Table 1).

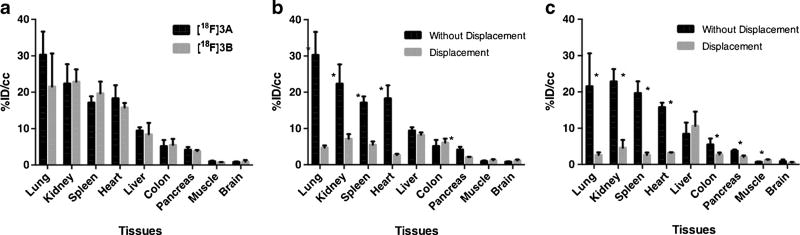

Biodistribution in Mice

Biodistribution of the two probes in healthy mice was characterized with cut-and-count analysis. We found a similar distribution pattern between [18F]3A and [18F]3B, with high absorption in TSPO-abundant tissues like lung, kidney, spleen, and heart; medium absorption in liver and colon; and low absorption in TSPO-deficient tissues like pancreas, muscle, and brain (Fig. 6a). Further analyses of the binding specificity and reversibility in healthy tissue were performed in displacement assays. Figure 6b, c, respectively, demonstrates that [18F]3A and [18F]3B could be displaced from the lung, liver, heart, kidney, and pancreas with their corresponding cold analogs.

Fig. 6.

Biodistribution of [18F]3A and [18F]3B in mice. a Direct comparison of %ID/cc for [18F]3A(n = 3) and [18F]3B in mice (n = 3). Direct comparison of %ID/cc for [18F]3A with/without injection of its cold analog 3A in mice (n = 3,*p < 0.05). c Direct comparison of %ID/cc for [18F]3B with and without injection of its cold analog 3B in mice (n = 3,*p < 0.05). Results = mean ± range.

Whole Body PET Imaging with [18F]3B

Whole body 60-min dynamic scan was performed with [18F]3B in a healthy Wistar rat (Supplemental Fig. 7). In this analysis, we observed a specific absorption of the probe in lung, kidney, heart, and liver (Supplemental Fig. 7a, b). The PET image is corresponding to the TACs obtained using TAC analysis as shown in Supplemental Fig. 7c.

Plasma Protein Binding Affinity

Higher k1/k2 values indicate a higher extraction rate for the probe in plasma, which can be associated with the plasma protein binding affinity. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 6, both 3A and 3B exhibited lower unbound fraction than DPA-714. Further, 3B exhibited 0.54 % more unbound fraction compared with 3A, which likely contributed to the enhanced tissue delivery observed.

Discussion

Our prior research has explored TSPO as a target for molecular imaging of cancer [14, 17, 22, 29, 30]. We have reported preclinical utilization of pyrazolopyrimidine PET probes for quantitative assessment of TSPO expression in glioma, which include the previously reported [18F]DPA-714 [17] and the novel TSPO ligand [18F]VUIIS1008 [18, 19] developed in our lab. In prior studies using these tracers, C6 tumors could be detected from the surrounding normal brain; moreover, quantitative analyses of the PET data agreed with ex vivo measures of TSPO levels [17–19]. This work also showed that improved TSPO affinity and PET imaging characteristics were a result of targeted modification of the pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold, specifically at the 5- and 7-positions. These studies prompted our lab to continue development of novel TSPO PET probes with improved properties for cancer imaging.

In this study, further exploration of the 5- and 7-positions on the pyrazolopyrimidine ring yielded two novel and high-affinity TSPO ligands, which are VUIIS1009A (3A) and VUIIS1009B (3B). The structural modifications of 3A (5-methyl, 7-ethyl) and 3B (5-ethyl, 7-methyl) afforded the ligands a number of improved properties for cancer imaging. Both demonstrated comparable in vitro binding affinities (14.4 versus 19.4 pM, respectively) that were not only a 20-fold improvement over their immediate predecessor (2) but also 500-fold greater than the original lead ligand (1). 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectroscopy showed the TSPO binding pockets created by 3A and 3B to be very similar to the pocket created by 1, suggesting shared pharmacodynamics among these pyrazolopyrimidine TSPO ligands. The radio-labeling conditions developed for ligand 2 were easily adapted to accommodate synthesis of evaluation of [18F]3A and [18F]3B.

In order to evaluate their in vivo performance, we performed 60-min dynamic PET scans on C6 glioma-bearing rats. PET imaging with these two probes demonstrated their capability to detect the tumor and correlated with T2 MRI, H&E, and TSPO IHC studies. Radiometabolite analysis of these two probes shows a higher stability for [18F]3A and a longer in vivo half-life, which will offer [18F] 3A some advantage for glioma imaging over [18F]3B. Further analysis of the PET data of [18F]3A and [18F]3B revealed twofold higher tumor uptake of [18F]3B relative to [18F]3A. This difference in uptake between [18F]3A and [18F]3B proved consistent with the total distribution volume (VT) values obtained from both Logan plot and parameter analyses. In both analyses, [18F]3B featured a higher VT value for both tumor and brain, when compared to [18F]3A, demonstrating the higher overall uptake potential of [18F]3B. Moreover, the ratio between VT for tumor and brain for [18F]3B indicated a significantly higher tumor-to-brain ratio when compared with [18F]3A. Subsequent displacement studies for both probes showed similar non-displaced radiotracers for both [18F]3A and [18F]3B (%ID/cc for non-displaced [18F]3A or [18F]3B is around 0.20 % at 60 min) but a significantly higher displacement ratio for [18F]3B. We propose that this higher displacement ratio of [18F]3B is due to its higher uptake in the tumor.

At the molecular level, both [18F]3A and [18F]3B exhibited similar binding affinity and binding pockets, while at the tissue-system level, they demonstrated significantly different in vivo performance. This difference could be explained by the pharmacokinetic analysis with kinetic modeling and kinetic parameter analysis. Based on our results of the two-compartment, four-parameter kinetic modeling, we found [18F]3B to have a similar tumor BPND and lower brain BPND relative [18F]3A. When compared with [18F]3A, we also noticed a significantly higher k1/k2 ratio for [18F]3B in both tumor and brain, indicating a higher plasma-to-tumor extraction efficacy for [18F]3B. We propose that this higher plasma-to-tumor extraction efficacy could be the reason for the higher tumor and brain uptake for [18F]3B.

Furthermore, by comparing the kinetic parameters between [18F]3A, [18F]3B, [18F]VUIIS1008, and [18F]DPA-714, we noticed a significant increase of BPND for both [18F]3A and [18F]3B, indicating their higher in vivo TSPO binding affinity and binding specificity. Meanwhile, we also noticed the decreased k1/k2 and VT for both [18F]3A and [18F]3B when compared with [18F]DPA-714 in tumor and brain, indicating their lower tumor and brain uptake. We propose that this lower tumor and brain uptake for [18F]3A and [18F]3B is the result of their higher plasma binding affinity. Besides this, [18F]3B demonstrated a higher VT ratio between tumor and brain when compared with [18F]DPA-714 (6.45 versus 4.38), indicating a higher tumor binding potential as compared to the healthy brain.

Conclusions

In this study, we report discovery of two high-affinity TSPO PET ligands and evaluation of their performance in preclinical glioma imaging. VUIIS1009A (3A) and VUIIS1009B (3B) exhibited exceptional binding affinity to TSPO and shared a common binding pocket within mTSPO. However, taking advantage of increased plasma-to-tumor extraction efficiency, [18F]VUIIS1009B exhibited superior imaging performance compared with [18F]VUIIS1009A. These studies highlight the important role of tissue delivery and may expand opportunities to utilize [18F]VUIIS1009B as a promising PET tracer for precision medicine deployment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dayo Felix and Daniel Colvin, Ph.D., for assistance with microPET and MR imaging studies, respectively, and Allie Fu for preclinical model support. The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (K25 CA127349, P50 CA128323, S10 RR17858, U24 CA126588, 1R01 CA163806) and the Kleberg Foundation.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11307-016-1027-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dhermain FG, Hau P, Lanfermann H, Jacobs AH, van den Bent MJ. Advanced MRI and PET imaging for assessment of treatment response in patients with gliomas. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:906–920. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu W, Le A, Hancock C, et al. Reprogramming of proline and glutamine metabolism contributes to the proliferative and metabolic responses regulated by oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8983–8988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203244109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaglio D, Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, et al. Oncogenic K-Ras decouples glucose and glutamine metabolism to support cancer cell growth. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:523. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JB, Erickson JW, Fuji R, et al. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batarseh A, Papadopoulos V. Regulation of translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) expression in health and disease states. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;327:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black KL, Ikezaki K, Toga AW. Imaging of brain tumors using peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligands. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:113–118. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.1.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starostarubinstein S, Ciliax BJ, Penney JB, Mckeever P, Young AB. Imaging of a glioma using peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:891–895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagler R, Ben-Izhak O, Savulescu D, et al. Oral cancer, cigarette smoke and mitochondrial 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO)—In vitro, in vivo, salivary analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venturini I, Zeneroli ML, Corsi L, et al. Diazepam binding inhibitor and total cholesterol plasma levels in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Regul Pept. 1998;74:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venturini I, Zeneroli ML, Corsi L, et al. Up-regulation of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor system in hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci. 1998;63:1269–1280. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardwick M, Fertikh D, Culty M, Li H, Vidic B, Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) in human breast cancer: correlation of breast cancer cell aggressive phenotype with PBR expression, nuclear localization, and PBR-mediated cell proliferation and nuclear transport of cholesterol. Cancer Res. 1999;59:831–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmel I, Fares FA, Leschiner S, Scherubl H, Weisinger G, Gavish M. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in the regulation of proliferation of MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cell line. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deane NG, Manning HC, Foutch AC, et al. Targeted imaging of colonic tumors in smad3−/− mice discriminates cancer and inflammation. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:341–349. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maaser K, Hèopfner M, Jansen A, et al. Specific ligands of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human colorectal cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(11):1771–1780. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maaser K, Grabowski P, Sutter AP, et al. Overexpression of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor is a relevant prognostic factor in stage III colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3205–3209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang D, Hight MR, McKinley ET, et al. Quantitative preclinical imaging of TSPO expression in glioma using N,N-diethyl-2-(2-(4-(2-18F-fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimi din-3-yl)acetamide. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53:287–294. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang D, McKinley ET, Hight MR, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 5,6,7-substituted pyrazolopyrimidines: discovery of a novel TSPO PET ligand for cancer imaging. J Med Chem. 2013;56:3429–3433. doi: 10.1021/jm4001874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang D, Nickels ML, Tantawy MN, Buck JR, Manning HC. Preclinical imaging evaluation of novel TSPO-PET ligand 2-(5,7-diethyl-2-(4-(2-[(18)F]fluoroethoxy)phenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)- N,N-diethylacetamide ([(18)F]VUIIS1008) in glioma. Molecular imaging and biology: MIB: the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging. 2014;16:813–820. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0743-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buck JR, McKinley ET, Fu A, et al. Preclinical TSPO ligand PET to visualize human glioma xenotransplants: a preliminary study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung YY, Nickels ML, Tang D, Buck JR, Manning HC. Facile synthesis of SSR180575 and discovery of 7-chloro-N,N,5-trimethyl-4-oxo-3(6-[(18)F]fluoropyridin-2-yl)-3,5-dihydro-4H-pyri dazino[4,5-b]indole-1-acetamide, a potent pyridazinoindole ligand for PET imaging of TSPO in cancer. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:4466–4471. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck JR, McKinley ET, Hight MR, et al. Quantitative, preclinical PET of translocator protein expression in glioma using 18F-N-fluoroacetyl-N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-2-phenoxyaniline. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52:107–114. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaremko L, Jaremko M, Giller K, Becker S, Zweckstetter M. Structure of the mitochondrial translocator protein in complex with a diagnostic ligand. Science. 2014;343:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.1248725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murail S, Robert JC, Coic YM, et al. Secondary and tertiary structures of the transmembrane domains of the translocator protein TSPO determined by NMR. Stabilization of the TSPO tertiary fold upon ligand binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan J. Graphical analysis of PET data applied to reversible and irreversible tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Liempd S, Morrison D, Sysmans L, Nelis P, Mortishire-Smith R. Development and validation of a higher-throughput equilibrium dialysis assay for plasma protein binding. Journal of laboratory automation. 2011;16:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Culty M, Silver P, Nakazato A, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor binding properties and effects on steroid synthesis of two new phenoxyphenyl-acetamide derivatives, DAA1097 and DAA1106. Drug Develop Res. 2001;52:475–484. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyatt SK, Manning HC, Bai M, et al. Molecular imaging of the translocator protein (TSPO) in a pre-clinical model of breast cancer. Molecular imaging and biology : MIB : the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging. 2010;12:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manning HC, Goebel T, Thompson RC, Price RR, Lee H, Bornhop DJ. Targeted molecular imaging agents for cellular-scale bimodal imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1488–1495. doi: 10.1021/bc049904q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.