Abstract

Background

The efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) has not been studied in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and left ventricular dysfunction. We sought to identify predictors of long-term survival among ICD recipients with and without ESRD.

Methods

Patients implanted with an ICD at our institution from January 2006 to March 2014 were retrospectively identified. Clinical and demographic characteristics were collected. Patients were stratified by the presence of ESRD at the time of ICD implant. Mortality data were collected from the Social Security Death Index (SSDI).

Results

A total of 3453 patients received an ICD at our institution in the pre-specified time period, 184 (5.3%) of whom had ESRD. In general, ESRD patients were sicker and had more comorbidities. Kaplan Meier survival curve showed that ESRD patients had worse survival as compared with non-dialysis patients (p<0.001). Following adjustment for differences in baseline characteristics, patients with ESRD remained at increased long-term mortality in the Cox model. The one-year mortality in the ESRD patients was 18.1%, as compared with 7.7% in the non-dialysis cohort (p<0.001). The three-year mortality in ESRD patients was 43%, as compared with 21% in the non-dialysis cohort (p<0.001).

Conclusion

ESRD patients are at significantly increased risk of mortality as compared with a non-dialysis cohort. While the majority of these patients survive more than one year post-diagnosis, the three-year mortality is high (43%). Randomized studies addressing the benefits of ICDs in ESRD patients are needed to better define their value for primary prevention of SCD.

Keywords: ESRD, Sudden cardiac death, ICD, Survival

1. Introduction

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality [1], in particular sudden cardiac death (SCD) [2], [3]. A subgroup at significant risk of arrhythmic death includes patients with ESRD and left ventricular dysfunction with low ejection fraction (EF) [4], [5]. These patients, however, have not been included in any of the known SCD primary prevention trials [6], [7], [8], and some data suggest indirectly that these patients may not derive any benefit from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) [9]. Furthermore, the competing arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic (cardiac and non-cardiac) causes of death in this population might make the benefit derived from ICDs negligible or neutral [1], [5], [10]. In addition, higher complication rates after implantation of ICDs in ESRD patients might contribute to the lack of observed ICD benefit in this population [5], [11].

The proportion of patients with ESRD in the United States is increasing [4], and physicians are increasingly faced with difficult clinical decisions when caring for the subgroup of patients with ESRD and low EF. Current guidelines suggest that patients referred for ICD implantation for primary prevention of SCD have an expected survival of more than one year [12]. In this study, we sought to determine the long-term survival of ICD recipients with ESRD as compared with those not receiving dialysis, and to determine predictors of long-term survival of ICD recipients.

2. Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed medical records for all patients undergoing de novo ICD implantation at Emory University hospital and Emory University hospital Midtown, two tertiary care hospitals located in metro Atlanta, Ga., from January 2006 to March 2014, and stratified them by the presence of ESRD at the time of implant. ESRD was defined by the need or lack of need for chronic dialysis (either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) at the time of device implant. The decision to implant a defibrillator, along with specific details of the implant procedure and type of device implanted (i.e., single chamber, dual chamber, or cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator [CRT-D]) was performed at the discretion of the treating physician. Baseline clinical characteristics and procedural details were ascertained from medical records review.

The primary endpoint for this analysis was all-cause mortality. Vital status was determined via a query of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI). Patients who could not be identified in the SSDI and for whom vital status could not be determined were excluded from this analysis.

The protocol for this study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board in June 2014 (IRB 00075736).

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical data are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Univariate analysis was performed using the Student׳s t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher׳s exact test, as appropriate. The time course of the primary endpoint, stratified by ESRD status, was assessed by Kaplan-Meier estimates and tested with the log-rank test. In order to identify correlations of mortality and assess for confounders, Cox proportional hazards models were performed, and univariate predictors with a p value≤0.1 were included in the multivariate model. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

A total of 3453 ICD implants were identified, of whom 184 (5.3%) had ESRD requiring chronic dialysis at the time of implant. From this group, we were able to determine mortality/survival data on 2554 patients (74%) who served as the final cohort for this analysis. Baseline characteristics, stratified by ESRD status, are presented in Table 1. Across the entire cohort, mean age at the time of implant was 59.6 years, and 66.8% of the patients were male, without significant differences between groups. However, as might be expected, the patients with ESRD were predominately sicker, as evidenced by a higher prevalence of comorbidities including diabetes (49.6% vs. 33.2%, p<0.001), hypertension (88.2% vs. 74.7%, p<0.001) and lower ejection fraction (EF) (22.3% vs. 25.6%, p=0.004). They were also more likely to be implanted with an ICD for secondary prevention of SCD (15.7% vs. 7.9%, p<0.001). The use of guideline-directed medical therapy including beta blockers was high (>85% in both groups), whereas there was a trend toward lower use of angiotensin antagonists among those with ESRD (63.8% vs. 71.8%, p=0.051). Approximately 39% of patients in both groups received cardiac resynchronization devices.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | non-ESRD (n=2427) | ESRD (n=127) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.6±14.5 | 59.1±14.9 | 0.705 |

| Male gender | 1615 (66.5) | 91 (71.7) | 0.234 |

| Left ventricle ejection fraction (%) | 25.6 ± 12.5 | 22.3 ± 9.7 | 0.004 |

| New York Heart Association class | 0.772 | ||

| I | 218 (9.0) | 14 (11.0) | |

| II | 946 (39.0) | 40 (31.5) | |

| III | 1214 (50.0) | 73 (57.5) | |

| IV | 49 (2.0) | 0 | |

| Primary prevention ICD indication | 2235 (92.1) | 107 (84.3) | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1085 (44.7) | 59 (46.5) | 0.696 |

| Prior CABG | 541 (22.3) | 36 (28.4) | 0.112 |

| Prior PCI | 548 (22.6) | 22 (17.3) | 0.165 |

| Chronic lung disease | 314 (12.9) | 20 (15.6) | 0.358 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 805 (33.2) | 63 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1812 (74.7) | 112 (88.2) | <0.001 |

| QRS duration | 121.5 ± 32.3 | 117.7 ± 28.8 | 0.196 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE-I/ARB | 1743 (71.8) | 81 (63.8) | 0.051 |

| Beta blockers | 2117 (87.2) | 108 (85.0) | 0.472 |

| Hydralazine | 244 (10.1) | 29 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Oral Nitrates | 298 (12.3) | 17 (13.4) | 0.711 |

| Digoxin | 530 (21.9) | 23 (18.1) | 0.322 |

| Diuretics | 1687 (69.5) | 68 (53.5) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 1715 (70.7) | 92 (72.4) | 0.667 |

| Clopidogrel | 451 (18.6) | 24 (18.9) | 0.928 |

| Warfarin | 626 (25.8) | 29 (22.8) | 0.459 |

| Statins | 1424 (58.7) | 78 (61.4) | 0.541 |

| Amiodarone | 65 (2.7) | 3 (2.4) | 0.826 |

| Defibrillator type | |||

| Single chamber | 1067 (44.0) | 61 (48.0) | 0.410 |

| Dual chamber | 413 (17.0) | 17 (13.4) | 0.331 |

| Cardiac resynchronization | 947 (39.0) | 49 (38.6) | 1.000 |

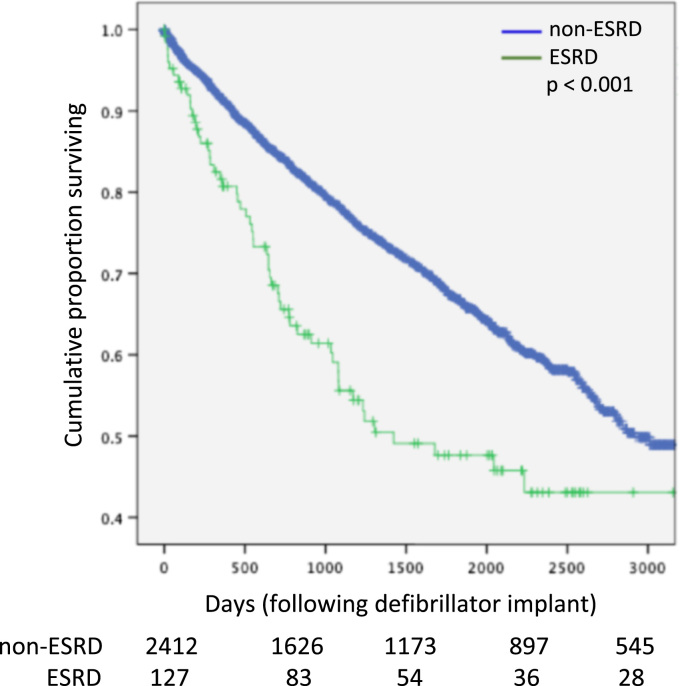

Kaplan Meier survival estimates (Fig. 1) demonstrated that patients with ESRD had significantly worse survival as compared with patients not on dialysis at the time of device implantation (p<0.001). In the ESRD cohort, 23 patients (18.1%) died within one year of device implant, as compared with 187 patients (7.7%, p<0.001) who died in the non-dialysis cohort.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meier (unadjusted) survival in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and non-ESRD cohorts.

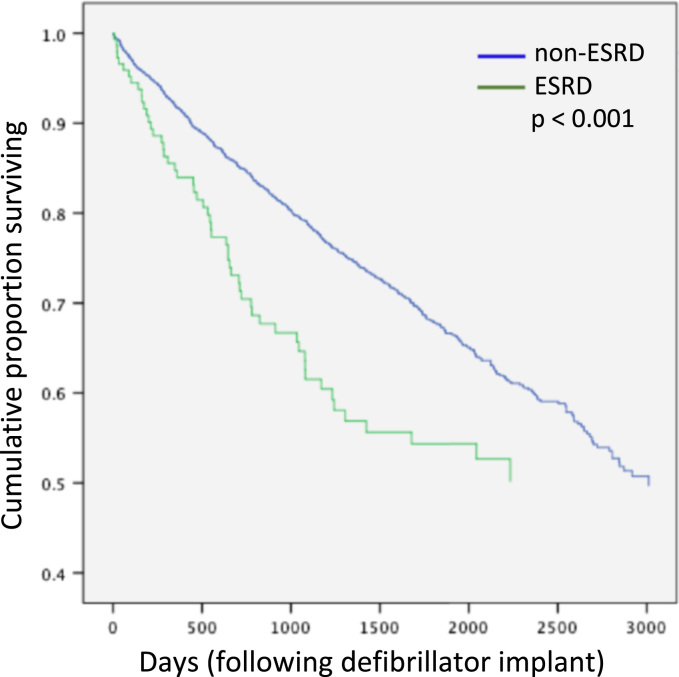

Given the presence of significant differences between the ESRD and non-ESRD cohorts at baseline, a multivariate analysis was performed. It demonstrated that secondary prevention ICD indication, presence of diabetes, diuretic use, lower ejection fraction, and ESRD remained significant predictors of mortality (Table 2). However, even after adjustment, patients with ESRD remained at significantly heightened risk for mortality in the Cox model (Fig. 2). In both unadjusted and adjusted analysis, at three years after ICD implant, the mortality rate was 43% among those with ESRD, as compared with 21% in the non-dialysis cohort (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariable predictors of mortality.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary prevention defibrillation indication | 1.364 | 1.022–1.821 | 0.035 |

| Diabetes | 1.244 | 1.062–1.456 | 0.007 |

| Diuretic use | 1.332 | 1.105–1.605 | 0.003 |

| Left ventricle ejection fractiona | 1.082 | 1.042–1.124 | <0.001 |

| End stage renal disease | 1.692 | 1.277–2.242 | <0.001 |

Per 5 point decrease in left ventricle ejection fraction.

Fig. 2.

Cox proportional hazards model for adjusted survival in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and non-ESRD cohorts.

One hundred and twelve patients with ESRD were followed up within our device clinic. Mean follow-up in this group was 856±816 days. Twenty-four patients (21.4%) received appropriate ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia over the duration of the follow-up.

4. Discussion

In this large study from two hospitals, we showed that patients with ESRD on dialysis have higher mortality than patients not on hemodialysis. As expected, the group of patients with ESRD was a sicker cohort with more comorbidities, which makes the interpretation of a non-adjusted comparison more difficult. However, even after adjusting for all of the differences between the two groups, patients with ESRD continued to have a worse prognosis. In fact, the adjusted survival curve was similar to the non-adjusted Kaplan Meier survival curve, implying that the presence of the survival difference between the two groups is mainly driven by the presence of ESRD.

Patients with ESRD are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality [13]. The latter is estimated to account for 43% of all instances of death in this patient population [2]. SCD accounts for the majority of cardiovascular death in this group of patients [2].

Primary prevention of SCD using ICDs is an established and effective therapy in patients with LV dysfunction [14]. However, patients with LV dysfunction and ESRD have not been included in any of the SCD primary prevention trials.

Data on the effects of ICD therapy on mortality in this patient population is mainly derived from different meta-analyses that have yielded conflicting results [1]. In a subgroup analysis of the MADIT-II trial, a decrease in eGFR was associated with an increase in SCD risk. Indeed, patients with moderate kidney disease appeared to derive significant survival benefits from ICD implantation. Surprisingly, patients with severe kidney insufficiency (eGFR <35 ml/min per 1.73 m2) showed no mortality reduction with the implantation of an ICD [9]. Similarly, a combined analysis from the three key primary prevention trials (MADIT-I, MADIT-II, SCD-HeFt showed a lack of benefits of ICD therapy in patients with an eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) [15]. In a propensity matched cohort study where 86 patients with ESRD with ICDs were matched to a group of patients with ESRD without ICDs, defibrillator therapy was not associated with a reduction in mortality (HR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.67–1.31, log-rank p=0.71) [16].

Other studies have shown a survival benefit of ICD use in patients with ESRD. A meta-analysis of retrospective studies by Chen et al. showed that patients with ESRD who were implanted with an ICD had better rates of survival as compared with patients without defibrillator [17]. In another study, Makki et al. showed in a pooled analysis of more than 17,000 patients that ICD therapy was associated with improved survival in patients with chronic kidney disease [18].

In a large study from the national cardiovascular data registry (NCDR) evaluating the survival of primary prevention ICD recipients, patients with CKD had higher mortality, as compared with patients without kidney disease [19]. The group with the worst survival was the group of patients on dialysis (HR=4.80; 95% confidence interval, 4.46–5.17, p<0.0001).

The major common finding in most of these studies is the high mortality of patients on dialysis. For instance, in a small study by Pun et al., the one-year mortality of ESRD patients with low EF was ≈40%, while the three-year mortality was ≈75% [16]. In a large study from the NCDR registry the one-year mortality of patients with ESRD with an ICD was 22.4%, and the three-year mortality was 49% [19].

In our study, the one-year mortality of ESRD patients was 18%, while the three-year mortality was 43%, results that are similar to the large NCDR study.

Despite the high-mortality rate of ESRD patients receiving an ICD, it appears that ≈ 80% of patients will survive to one year after an ICD implant. With respect to the study results on one-year expected survival rates prior to ICD implant, it can be argued that patients with ESRD should not be denied the potential benefit of an ICD. Nevertheless, the high three-year mortality and the lack of randomized clinical trials in this patient population necessitate a detailed discussion of pros and cons of this therapy prior to offering it to patients on dialysis.

4.1. Study limitations

This is a single center study with a relatively small number of patients. The survival data was only available in 74% of the entire cohort. However, the ability to statistically adjust for the differences between the two groups provides a robust statistical mean to validate other data that have been previously published. Unfortunately, we do not have information about the causes of death in our cohort. Therefore, only all-cause mortality was reported, and no information on cardiovascular death or sudden cardiac death could be presented. In addition, we do not have information on renal function in the non-dialysis cohort.

5. Conclusions

While the major cause of death in ESRD patients is known to be SCD, it is unclear whether ICD therapy can definitively improve survival in this group of patients. This study shows that while ESRD patients have high mortality as compared with non-dialysis patients, the majority would survive beyond one year after ICD implantation. Using the one-year arbitrary survival cut-off, these patients should not be denied the potential benefit of an ICD. Randomized controlled trials of ICD therapy in this sick cohort of patients are needed to better guide physicians when treating patients with ESRD and LV dysfunction.

Conflict of interest

Mikhael F. El-Chami is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Medtronic and has received a research grant from Medtronic.

The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Patton K.K., Poole J.E. Defibrillator therapy in chronic kidney disease: is it worth it? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(5):774–776. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog C.A., Mangrum J.M., Passman R. Sudden cardiac death and dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2008;21(4):300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2008.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genovesi S., Valsecchi M.G., Rossi E. Sudden death and associated factors in a historical cohort of chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(8):2529–2536. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitman I.R., Feldman H.I., Deo R. CKD and sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(12):1929–1939. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robin J., Weinberg K., Tiongson J. Renal dialysis as a risk factor for appropriate therapies and mortality in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(10):1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moss A.J., Zareba W., Hall W.J. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadish A., Dyer A., Daubert J.P. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2151–2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardy G.H., Lee K.L., Mark D.B. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldenberg I., Moss A.J., McNitt S. Multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial III: relations among renal function, risk of sudden cardiac death, and benefit of the implanted cardiac defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakhuja R., Keebler M., Lai T.S. Meta-analysis of mortality in dialysis patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(5):735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tompkins C., McLean R., Cheng A. End-stage renal disease predicts complications in pacemaker and ICD implants. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22(10):1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein A.E., DiMarco J.P., Ellenbogen K.A. ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013. 2012;61(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. [e6-75] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saravanan P., Freeman G., Davidson N.C. Risk assessment for sudden cardiac death in dialysis patients: how relevant are conventional cardiac risk factors? Int J Cardiol. 2010;144(3):431–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy C.M., Epstein A.E., Darbar D. ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Heart Rhythm. 2012;2012(9):1737–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pun P.H., Al-Khatib S.M., Han J.Y. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in CKD: a meta-analysis of patient-level data from 3 randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(1):32–39. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pun P.H., Hellkamp A.S., Sanders G.D. Primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-stage kidney disease patients on dialysis: a matched cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(5):829–835. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen T.H., Wo H.T., Chang P.C. A meta-analysis of mortality in end-stage renal disease patients receiving implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e99418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makki N., Swaminathan P.D., Hanmer J. Do implantable cardioverter defibrillators improve survival in patients with chronic kidney disease at high risk of sudden cardiac death? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Europace. 2014;16(1):55–62. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess P.L., Hellkamp A.S., Peterson E.D. Survival after primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement among patients with chronic kidney disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(5):793–799. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]