Abstract

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) using a biventricular pacing system has been an effective therapeutic strategy in patients with symptomatic heart failure with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and a QRS duration of 130 ms or more. The etiology of heart failure can be classified as either ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Ischemic etiology of patients receiving CRT is prevalent predominantly in North America, moderately in Europe, and less so in Japan. CRT reduces mortality similarly in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, whereas reverse structural left ventricular remodeling occurs more favorably in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Because the substrate for ventricular arrhythmias appears to be more severe in cases of ischemic as compared with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, the use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) backup method could prolong the long-term survival, especially of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, even in the presence of CRT. The aim of this review article is to summarize the effects of CRT on outcomes and the role of ICD backup in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: Cardiac resynchronization therapy, CRT, Ischemic cardiomyopathy, Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, Reverse remodeling, Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, ICD

1. Introduction

Cumulative survival from all-cause mortality decreases proportionally with QRS duration in patients with advanced heart failure [1]. Prolongation of QRS duration with left bundle-branch block (LBBB) morphology imposes left ventricle (LV) activation delay via a transmural functional line of block located between the LV septum and the lateral wall [2], resulting in ventricular dyssynchrony. Optimization of cardiac performance had been proposed by use of biventricular pacing in patients with drug-refractory congestive heart failure and an intraventricular conduction delay using the epicardial [3], [4] and subsequently, a transvenous route with electrodes selectively inserted in the cardiac veins through coronary sinus over the LV free wall [5]. The MIRACLE (Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation) study proved the clinical benefits of atrial-synchronized biventricular pacing in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure (New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV) who had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and a QRS interval of 130 ms or more [6]. This biventricular pacing system has been called cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and become an established therapeutic approach for symptomatic heart failure with prolonged QRS duration.

With regards to mortality, the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) study demonstrated for the first time a better prognosis of patients with CRT plus a defibrillator (CRT-D) than those using optimal pharmacologic therapy alone [7]. In the subgroup analyses, hazard ratios for death from any cause of CRT-D as compared with pharmacologic therapy were 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 1.04, P = 0.082) and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.29 to 0.88, P = 0.015) in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, respectively. A test for the interaction between the treatment effects and the etiology of cardiomyopathy was not significant [7]. In the Cardiac Resynchronization – Heart Failure (CARE-HF) study, CRT reduced all-cause mortality similarly in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [8], [9]. In agreement, the survival benefit with CRT-D over an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was consistent in a subgroup analysis of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and in those with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [10], [11]. This review article aims to summarize the effects of CRT on outcomes and the importance of ICD backup in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

2. Current guidelines and appropriate use criteria for CRT

According to current guidelines in the United State (US) and Europe, CRT is indicated as class I (i.e., a procedure or treatment that should be performed where the benefits outweigh the risks) for patients who have LVEF of 35% or less: LBBB with a QRS duration of 150 ms [12] (130 ms [13]) or greater; and NYHA class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms on guideline-directed medical therapy. In addition, CRT may be considered to be appropriate for patients who have LVEF of 30% or less, LBBB with a QRS duration of 150 ms or greater, and NYHA class I, if the etiology of heart failure is ischemic [14]. The latter recommendation is based on the limited data from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) study, in which patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and NYHA class I were enrolled in about 15% of total subjects [11]. In MADIT-CRT, patients with ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, LVEF of 30% or less, and a QRS duration of 130 ms or more, were randomly assigned to receive CRT plus a defibrillator (CRT-D), or an ICD alone. CRT-D (compared with ICD) was found to reduce the primary endpoint, death from any cause or a nonfatal heart-failure event (hazard ratio in the CRT–D group, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.84; P = 0.001). In this regard, the MADIT-CRT study demonstrated the effectiveness of CRT in combination with a defibrillator; that is, (a) the treatment of heart failure with reverse remodeling by using CRT, and (b) the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death by using a defibrillator.

3. Proportion of ischemic and non-ischemic etiology in CRT recipients in North America, Europe, and Japan

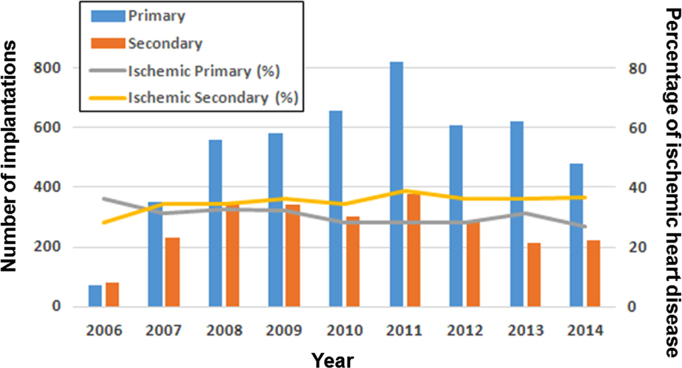

The rate of ischemic heart failure patients was over 50% in most of the randomized studies of CRT conducted in North America and Europe [6], [7], [10], [11], [15], [16], [17], except for 36% in CARE-HF (Cardiac Resynchronization – Heart Failure) [8] (Table 1). This trend is consistent with that in a cohort study using the National Impatient Sample (NIS), which is the publicly-available healthcare database in the United States (US) [18]. It is interesting to know that the CARE-HF study enrolled patients at only European centers, and that the CeRtiTude cohort study [19], which enrolled ischemic cardiomyopathy less than 50%, was also conducted in Europe. In contrast, patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy were most common at a rate of about 70% in Japan, on the basis of the Japan Cardiac Device Treatment Registry (JCDTR) database [20] (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The rate of ischemic etiology and medications in clinical studies of CRT.

| Study (published year) (Number of patients) | F/U (mo.) | Eligible subjects | Isch. | ACEI /ARB | Beta. | MRA | Outcomes with CRT-P or CRT-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | |||||||

| MIRACLE (2002) (n=453) [6] | 6 | NYHA III, IV | 58% | 90% | 55% | Decrease in mortality or HF hospitalization | |

| LVEF≦35% | |||||||

| CRT-P vs Control, HR 0.60 (95% CI 0.37–0.96), P=0.03 | |||||||

| QRS≧130 ms | |||||||

| MIRACLE-ICD (2003) (n=325) [17] | 6 | NYHA III, IV | 76% | 89% | 58% | Decrease in NYHA functional class, P=0.007 | |

| LVEF≦35% | |||||||

| Increase in peak oxygen consumption, P=0.04 | |||||||

| QRS≧130 ms | |||||||

| COMPANION (2004) (n=1520) [7] | 15 | NYHA III, IV | 56% | 89% | 66% | 55% | Decrease in mortality |

| CRT-D vs Control, HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.48–0.86), P=0.003 | |||||||

| LVEF≦35% | |||||||

| QRS≧120 ms | |||||||

| CRT-P vs Control, HR 0.76 (95% CI 0.58–1.01), P=0.059 | |||||||

| CARE-HF (2005) (n=813) [8] | 29 | NYHA III, IV | 36% | 95% | 74% | 59% | Decrease in mortality |

| LVEF≦35% | CRT-P vs Control, HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.48–0.85) | ||||||

| QRS≧120 ms | |||||||

| REVERSE (2008) (n=610) [15] | 12 | NYHA I, II | 51% | 97% | 94% | Decrease in HF hospitalization | |

| LVEF≦40% | |||||||

| A greater improvement in LVESV | |||||||

| QRS≧120 ms | |||||||

| MADIT-CRT (2009) (n=1820) [11] | 29 | NYHA I, II | 55% | 97% | 93% | 31% | Decrease in mortality or HF |

| LVEF≦30% | |||||||

| CRT-D vs ICD, HR 0.66 (95% CI 0.52–0.84), P=0.001 | |||||||

| QRS≧130 ms | |||||||

| MADIT-CRT (2014) (n=854) [10] | 84 | NYHA I, II | 53% | 97% | 94% | Decrease (LBBB) and increase (non-LBBB) in mortality | |

| LVEF≦30% | |||||||

| CRT-D in LBBB, HR 0.59 (95% CI 0.43–0.80), P<0.001 | |||||||

| QRS≧130 ms | |||||||

| CRT-D in non-LBBB, HR 1.57 (95% CI 1.03–2.39), P=0.04 | |||||||

| RAFT (2010) (n=1798) [16] | 40 | NYHA II, III | 65% | 97% | 89% | 42% | Decrease in mortality |

| LVEF≦30% | CRT-D vs ICD, HR 0.75 (95% CI 0.62–0.91), P=0.003 | ||||||

| QRS≧120 ms | |||||||

| Observational study | |||||||

| CeRtiTuDe (2015) (n=1705) [19] | 22 | 47% | 66% | 75% | 41% | Decrease in mortality | |

| CRT-D vs CRT-P, HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.45–0.93), P=0.0209 | |||||||

| NIS database (2016) (n=311085) [18] | 66% | ||||||

| JCDTR (2016) (n=3269) [20] | 28% | 67% | 78% | 42% |

F/U: follow-up period; mo.: months; Isch: ischemic cardiomyopathy; ACEI/ARB: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; Beta: beta-blocker; MRA: mineral corticoid receptor antagonist; CRT-P: CRT pacemaker; CRT-D: CRT with a defibrillator; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; RCT: randomized controlled trial; HF: heart failure; HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; LVESV: left ventricular end-systolic volume; NIS: National Inpatient Sample; JCDTR: Japan Cardiac Device Treatment Registry. The JCDTR was established in 2006 by the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society (JHRS) for a survey of actual conditions in patients undergoing implantation of cardiac implantable electronic devices (ICD/CRT-D/CRT-P) [20], [54], [55], [56].

Fig. 1.

Annual distribution of CRT-D implantations in heart failure patients for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death between 2006 and 2014 from the Japan Cardiac Device Treatment Registry (JCDTR) database. Distribution of CRT-D implantations for primary (blue vertical column) and secondary (orange vertical column) prevention. The gray and yellow lines indicate the proportion of ischemic cardiomyopathy for primary and secondary prevention, respectively. These results were presented at the 8th Implantable Cardiac Device Conference of the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society held on February 7, 2016. CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy (= biventricular pacing); CRT-D: CRT with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

With regard to medication, patients in the cohort studies were less likely to receive angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI)/ angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and/or beta-blockers compared with those in the contemporary randomized studies.

4. Reverse remodeling with CRT in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy

The rate of responders assessed by the improvement of NYHA class status in the MIRACLE study was 67% in the CRT group, and was significantly higher than that (38%) in the control group [6]. More objectively, patients with echocardiographic changes of 25% (or 15% [21]) reduction in left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), 15% reduction in left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), 20% reduction in left atrial volume (LAV) and/or 8% increase in LVEF, a year following CRT, have been considered to show favorable responses and significant reverse remodeling [22].

Gasparini et al. reported for the first time that patients with non-ischemic etiology had a greater increase in LVEF and a decrease in NYHA functional class after CRT than did patients with ischemic heart disease [23]. Sub-analysis of the prospective randomized studies including MIRACLE (Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation) [24], CARE-HF [9], REVERSE (REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction) [25] and MADIT-CRT [22] confirmed the occurrence of more favorable reverse remodeling in non-ischemic than in ischemic cardiomyopathy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reverse remodeling with CRT in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

| Study | Measured at (months) | Etiology | ⊿LVEDV | ⊿LVESV | ⊿LVEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIRACLE [24] | 12 | Ischemic | NS | NS | Increase |

| Non-ischemic | Decrease⁎ | Decrease⁎ | Increase⁎ | ||

| REVERSE [25] | 12 | Ischemic | Decrease | Decrease | Increase |

| Non-ischemic | Decrease | Decrease⁎ | Increase† | ||

| CARE-HF [9] | 18 | Ischemic | Decrease | Increase | |

| Non-ischemic | Decrease⁎ | Increase† | |||

| MADIT-CRT [22] | 12 | Ischemic | Decrease | Decrease | Increase |

| Non-ischemic | Decrease† | Decrease† | Increase† |

Isch: ischemic cardiomyopathy; Non-isch: non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; LVEDV: left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV: left ventricular end-systolic volume; ⊿: change from baseline; NS: not significant.

The degree of these changes was greater in non-ischemic vs ischemic cardiomyopathy when the between-group comparison was significant (i.e., ⁎ or †).

P < 0.05 for interaction or between-group (ischemic vs non-ischemic) comparison.

P < 0.005 for interaction or between-group (ischemic vs non-ischemic) comparison.

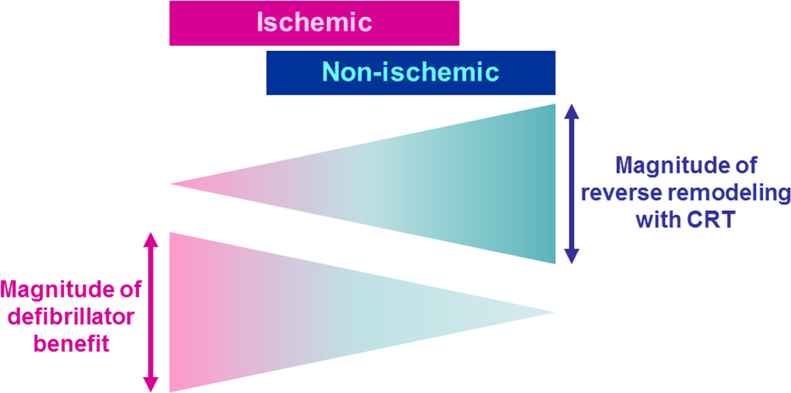

Goldenberg et al. identified factors associated with reverse remodeling following CRT using data from MADIT-CRT, and created a response score [26] (Table 3). They proposed a combined assessment of these factors for improved selection of patients for CRT. A similar analysis was performed for predicting patients with LVEF normalization (> 50%), which found a total of six relevant factors: female gender, non-ischemic etiology, LBBB, baseline LVEF>30%, LVESV≤170 mL and LAV index≤45 mL/m2 [27]. Therefore, it is an undoubted fact that non-ischemic cardiomyopathy shows a better response with regard to reverse LV structural remodeling than ischemic cardiomyopathy (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Factors associated with favorable reverse remodeling following CRT.

| Regression coefficienta | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 2.92 | 2 |

| Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy | 4.16 | 2 |

| QRS ≧ 150 ms | 2.67 | 2 |

| LBBB | 2 | |

| Prior HF hospitalization | 1.88 | 1 |

| Baseline LVEDV ε 125 mL/m2 | 4.18 | 2 |

| Baseline LAV < 40 mL/m2 | 5.57 | 3 |

LBBB: left bundle-branch block; HF: heart failure; LVEDV: left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LAV: left atrial volume.

This table was made based on the data from Goldenberg et al. [26].

The multivariate regression model was obtained for LVEDV reduction at 1 year following CRT. Regression coefficients for each predictor covariate are given.

Fig. 2.

The diagram for magnitude of therapeutic effects of CRT with a defibrillator on ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Reverse remodeling with CRT occurs more favorably in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy than in ischemic cardiomyopathy. The arrhythmogenic substrate is more intractable in ischemic cardiomyopathy, which can benefit significantly from a defibrillator. CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy (= biventricular pacing).

5. The effects of CRT on morbidity and mortality in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy

On the basis of sub-analysis of the CARE-HF study, CRT decreased the primary composite endpoint (i.e., all-cause mortality or hospitalization for a major cardiovascular event) and principal secondary endpoint (i.e., all-cause mortality) in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [9]. Patients with ischemic etiology were older, with a higher prevalence of male gender, and were more likely to be NYHA class IV, indicating the presence of more advanced heart failure. The authors concluded (a) the benefits of CRT in patients with or without ischemic heart disease were similar in relative terms, (b) but as patients with ischemic heart disease had a worse prognosis, the benefit for them in absolute terms may be greater. However, it is interesting to know the marginal statistical significance of interaction (P = 0.06) between ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, in terms of two hazard functions for the primary composite end points (ischemic: hazard ratio 0.72; 95% CI 0.54–0.95; non-ischemic: hazard ratio 0.48; 95% CI 0.35–0.65) [9].

Barsheshet et al. sought to identify factors associated with a reduction in heart failure or death in response to CRT-D as compared with ICD in the MADIT-CRT study [22]. Such factors in ischemic cardiomyopathy were (a) QRS duration ≥ 150 ms, (b) systolic blood pressure < 115 mmHg and (c) LBBB, whereas in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, (a) females, (b) patients with diabetes mellitus and (c) LBBB showed a favorable clinical response [22] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with reduction of heart failure or death with CRT-D versus ICD in each etiology group.

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | |||

| QRS ≧ 150 ms | 0.53 (0.38 – 0.73) | < 0.001 | P=0.04 |

| QRS < 150 ms | 0.89 (0.60 – 1.31) | 0.55 | |

| Systolic blood pressure < 115 mmHg | 0.48 (0.32 – 0.72) | < 0.001 | P=0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure ε 115 mmHg | 0.80 (0.58 – 1.11) | 0.18 | |

| LBBB | 0.47 (0.34 – 0.65) | < 0.001 | P=0.002 |

| Non-LBBB | 1.09 (0.72 – 1.65) | 0.68 | |

| Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy | |||

| Female | 0.25 (0.14 – 0.46) | < 0.001 | P=0.001 |

| Male | 0.90 (0.54 – 1.46) | 0.67 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (+) | 0.31 (0.16 – 0.61) | < 0.001 | P=0.05 |

| Diabetes mellitus (−) | 0.67 (0.44 – 1.04) | 0.08 | |

| LBBB | 0.42 (0.28 – 0.62) | < 0.001 | P=0.011 |

| Non-LBBB | 1.57 (0.61 – 4.04) | 0.35 | |

This table was made based on the data from Barsheshet et al. [22].

A meta-analysis using individual patient-data from five randomized trials, with adjustment of the baseline variables including age, sex, NYHA class, etiology, QRS morphology and duration, LVEF and systolic blood pressure, concluded that only QRS duration (≥ 140 ms), and not the etiology of heart failure, predicted the magnitude of the effects of CRT on morbidity and mortality [28]. Taken together, CRT appears to reduce the mortality of both groups similarly.

6. The role of a defibrillator in ischemic and non-ischemic heart failure patients receiving CRT

Witt et al. reported that CRT-D reduced mortality as compared with CRT-P (biventricular pacemaker without a defibrillator) in an observational study that enrolled 917 heart failure patients (427 with non-ischemic, and 490 with ischemic cardiomyopathy) who had LVEF of 35% or less and a QRS duration of 120 ms or greater [29]. However, only patients with ischemic etiology, benefited significantly from a defibrillator. In addition, even in the cases of responders (who were defined by an improvement of NYHA functional class at the six-month follow-up visit with CRT), ICD backup (CRT-D) was a predictor of longer survival in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy [29]. A similar retrospective study by Kutyifa et al. concluded that CRT-D in ischemic cardiomyopathy was associated with a mortality benefit as compared with CRT-P, but no benefit of CRT-D over CRT-P in mortality was observed in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [30] (Table 5). A meta-analysis of effects of ICD backup in CRT recipients revealed significant associations between male gender or ischemic cardiomyopathy and a stronger benefit of CRT-D [31].

Table 5.

Studies and Ischemic Etiology Comparing Outcomes with CRT-D Versus CRT-P.

| Study (year) | F/U (mo.) | Number of patients | Isch. | Male | Age (years). | NYHA | Mortality with CRT-D vs CRT-Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | |||||||

| COMPANION (2004) (n = 1520) [7] | 15 | CRT-D 595 | 55% | 67% | 66 | III 86% | CRT-D vs Ctrl, HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.48-0.86), P=0.003 |

| CRT-P 617 | 54% | 67% | 67 | III 87% | |||

| Ctrl 308 | 59% | 69% | 68 | III 82% | CRT-P vs Ctrl, HR 0.76 (95% CI 0.58-1.01), P=0.059 | ||

| REVERSE (2013) (n = 419) [57] | 60 | CRT-D 345 | 59%b | 79% | 63 | II 82% | Decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 74 | 46% | 72% | 64 | II 81% | HR 0.35 (95% CI 0.17-0.69), P=0.003 | ||

| MASCOT (2013) (n = 402) [58] | 12 | CRT-D 228 | 60%b | 86%b | 68 | III 87% | Lack of decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 174 | 38% | 70% | 68 | III 83% | |||

| Observational study | |||||||

| Contak IR (2013) (n = 374) [59] | 55 | CRT-D 266 | 62%b | 85%b | 67b | III 61% | Decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 108 | 41% | 68% | 74 | III 64% | HR 0.51 (95% CI 0.32-0.83), P=0.007 | ||

| Kutyifa et al (2014) (n = 1122) [30] | 28 | CRT-D 429 | 51%b | 84%b | 64b | Decrease in mortality of Isch | |

| HR 0.98 (95% CI 0.73-1.32), P=0.884 | |||||||

| Isch HR 0.70 (95% CI 0.50-0.97), P=0.032 | |||||||

| CRT-P 693 | 34% | 71% | 66 | ||||

| Non-isch HR 0.98 (95% CI 0.73-1.32), P=0.894 | |||||||

| Looi et al (2014) (n = 500) [60] | 29 | CRT-D 146 | 66%b | 91%b | 67b | III/IV 88%b | Lack of decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 354 | 48% | 73% | 70 | III/IV 94% | HR 0.76 (95% CI 0.48-1.12), P=0.23 | ||

| CeRtiTuDe (2015) (n = 1705) [19] | 22 | CRT-D 1170 | 49%b | 81%b | 66b | III 76% | Decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 535 | 41% | 70% | 76 | III 76% | HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.45-0.93), P=0.0209 | ||

| Reitan et al (2015) (n = 705) [61] | 59 | CRT-D 257 | 52%b | 84% | 65b | III 59%b | Lack of decrease in mortality |

| CRT-P 448 | 60% | 83% | 72 | III 77% | HR 0.63 (95% CI 0.38-1.09), P=0.103 | ||

| Witt et al (2016) (n = 917) [29] | 48 | CRT-D 428 | 71%b | 86%b | 67b | III 63%b | Decrease in mortality |

| HR 0.76 (95% CI 0.60-0.97), P=0.03 | |||||||

| CRT-P 489 | 38% | 75% | 69 | III 76% | |||

| Isch HR 0.74 (95% CI 0.56-0.97), P=0.03 | |||||||

| Non-isch HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.60-1.51), P=0.85 | |||||||

| Barra et al (2016) (n = 638) [62] | 49 | CRT-D 224 | 61%b | 88%b | 66b | III/IV 86%b | Decrease in mortality of GS 0-2 |

| GS 0-2 HR 0.34 (95% CI 0.18-0.64), P=0.001 | |||||||

| CRT-P 414 | 48% | 73% | 70 | III/IV 95% | GS 3-5 Lack of decrease in mortality | ||

| Munir (2016) (n = 512) [63] | 41 | CRT-D 405 | 57%b | 73% | 81b | Lack of decrease in mortality | |

| CRT-P 107 | 30% | 64% | 83 | HR 0.85 (95% CI 0.56-1.28), P=0.435 | |||

| Patients with age ≧75 years were eligible. |

F/U: follow-up period; mo.: months; Isch: ischemic cardiomyopathy; CRT-P: CRT pacemaker; CRT-D: CRT with a defibrillator; Ctrl: control (without CRT devices); RCT: randomized controlled trial; HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; MOSCOT: Management of Atrial fibrillation Suppression in AF-HF Comorbidity Therapy; Contak IR: Contak Italian Registry; Isch: ischemic cardiomyopathy; Non-isch: non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; GS: Goldenberg risk score. The Goldenberg risk score model comprised five clinical factors including (i) NYHA class > II, (ii) AF, (iii) QRS duration > 120 ms, (iv) age > 70 years and (v) blood urea nitrogen (BUN) > 26 mg/dL [64].

In COMPANION [7], the effect of CRT-D versus CRT-P on mortality was not compared. In other studies, hazard ratios of CRT-D versus CRT-P are given in this table.

P < 0.05 vs CRT-P

In contrast to ischemic etiology [32], [33], [34], the efficacy of ICD implantation for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death was conflicting in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy [35], [36], [37], [38], [39] (Table 6). The DANISH trial (Danish Study to Assess the Efficacy of ICDs in Patients with Non-ischemic Systolic Heart Failure on Mortality) recently demonstrated that the addition of ICD function fails to prolong survival in symptomatic heart failure patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy who have LVEF of 35% or less [38]. In this study, the rate of patients who had CRT was 58%, and the effects of ICD implantation was independent of CRT status (P = 0.73 for the interaction). Therefore, it appears that the arrhythmogenic substrate itself is more severe in cases of ischemic cardiomyopathy, compared with that of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Table 6.

Randomized controlled trials for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death by ICD in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

| n | NYHA class | LVEF | Death from any cause (ICD vs Control) | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT [35] | 104 | II, III | ≤30% | Lack of decrease in mortality | |

| AMIOVIRT [39] | 103 | I, II, III | ≤35% | Lack of decrease in mortality | ICD vs amiodarone |

| DEFINITE [37] | 458 | I, II, III | ≤35% | HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.40–1.06; P = 0.08 | No mortality benefit in NYHA II |

| HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.15–0.90; P = 0.02 (NYHA III) | |||||

| SCD-HeFT [36]a | 2521 | II, III | ≤35% | HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.62–0.96; P = 0.007 | No mortality benefit in NYHA III |

| HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.50–1.07; P = 0.06 (Non-ischemic) | |||||

| DANISH [38] | 1116 | II, III, IV | ≤35% | Lack of decrease in mortality | CRT 58% |

n: number of patients; CAT: Cardiomyopathy Trial; AMIOVIRT: Amiodarone Versus Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator; DEFINITE: Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation; SCD-HeFT: Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial; DANISH: Danish Study to Assess the Efficacy of ICDs in Patients with Non-ischemic Systolic Heart Failure on Mortality; HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Except for SCD-HeFT, the etiology of cardiomyopathy in eligible subjects was non-ischemic in CAT, AMIOVIRT, DEFINITE, and DANISH. Proportion of non-ischemic etiology was 48% in SCD-HeFT.

7. Promising strategies for better response to CRT in ischemic cardiomyopathy

Bleeker et al. reported that presence of transmural scar tissue in the posterolateral LV segments (where a LV lead was implanted most frequently [40]) often resulted in clinical and echocardiographic nonresponse to CRT in ischemic cardiomyopathy [41]. Moreover, using two-dimensional speckle tracking imaging, LV lead position at the myocardial scar or discordant area (which is outside the latest activated segment) were independent determinants of worse prognosis during the long-term follow-up in ischemic heart failure patients treated with CRT [42].

A strategy to implant a LV lead to the latest activated segment was effective in reducing the primary composite endpoint of mortality and heart failure hospitalization in the TARGET (Targeted Left Ventricular Lead Placement to Guide Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) [43] and STARTER (Speckle Tracking Assisted Resynchronization Therapy for Electrode Region) [44] studies. A sub-analysis of STARTER reported that echocardiography-guided LV lead placement improved CRT-D therapy (shock or anti-tachycardia pacing)-free survival more favorably in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy to a level comparable to that of non-ischemic etiology [45]. As such, further clinical studies are required to determine whether the echocardiography-guided LV lead implantation reduces the incidence of sustained ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Optimization of atrioventricular, as well as interventricular, delay shortens isovolumic contraction time, thereby increasing the effective diastolic filling time and the stroke volume [46]. Marsan et al. reported that the optimization of sequential biventricular pacing via adjustment of the V-V interval further increased LV systolic performance, particularly in ischemic cardiomyopathy [47]. They also found that the degree of pre-stimulation of the LV was positively correlated with an amount of scar volume with regard to its optimization.

An LV lead that is designed with four electrodes is capable of delivering two LV pulses per pacing cycle when it is connected to a CRT device with the ability to deliver multipoint pacing (MPP) [48], [49], [50]. Clinical data is accumulating regarding the long-term effects of MPP, mainly in Europe. The responder rate has been reported to be higher (76% [49], 90% [50]) in patients with MPP than those (about 60% [49], [50]) with conventional CRT. Although MPP did not further improve acute hemodynamic response in patients who responded favorably to conventional biventricular pacing [51], [52], non-responders with non-LBBB appeared most likely to derive benefit from use of MPP [51]. In addition, a heart model in silico predicted that MPP offered an improved response over conventional CRT in cases in which a larger scar was present in the posterolateral region [53]. Consistently, in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy in whom the LV lead was deployed over an LV free wall scar, MPP proved to be the most optimal, as compared with single-site LV pacing methods, in terms of acute hemodynamic response [52]. We anticipate that MPP is superior to conventional CRT, especially in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and a large scar in the LV free wall.

8. Conclusions

The effects of CRT on mortality are not heterogeneous among patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. In contrast, it appears that CRT offers a more favorable response with regard to reverse LV remodeling in cases of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, the substrate for ventricular arrhythmias in ischemic cardiomyopathy appears to be more severe compared with non-ischemic etiology, thereby playing an essential role of ICD backup, especially in cases of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Both the implantation of an LV lead to the latest activated segment and MPP via a quadripolar LV lead are promising concepts for an improved response to CRT in ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgments

H Yokoshiki thanks Dr. Masayuki Sakurai, Director of Hokko Memorial Hospital, for constant encouragement of this work.

References

- 1.Gottipaty V.K., Krelis S.P., Lu F. The resting electrocardiogram provides a sensitive and inexpensive marker of prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:145. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auricchio A., Fantoni C., Regoli F. Characterization of left ventricular activation in patients with heart failure and left bundle-branch block. Circulation. 2004;109:1133–1139. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118502.91105.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakker P.F., Meijburg H., de Jonge N. Beneficial effects of biventricular pacing in congestive heart failure. PACE. 1994;17:820. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazeau S., Ritter P., Bakdach S. Four chamber pacing in dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1994;17:1974–1979. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1994.tb03783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daubert J.C., Ritter P., Le Breton H. Permanent left ventricular pacing with transvenous leads inserted into the coronary veins. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham W.T., Fisher W.G., Smith A.L. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1845–1853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow M.R., Saxon L.A., Boehmer J. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleland J.G., Daubert J.C., Erdmann E. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wikstrom G., Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Andren B. The effects of aetiology on outcome in patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy in the CARE-HF trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:782–788. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg I., Kutyifa V., Klein H.U. Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1694–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss A.J., Hall W.J., Cannom D.S. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;2013(128):e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponikowski P., Voors A.A., Anker S.D. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;2016(37):2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo A.M., Stainback R.F., Bailey S.R. Vol. 61. 2013. ACCF/HRS/AHA/ASE/HFSA/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2013 appropriate use criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation appropriate use criteria task force, Heart Rhythm Society, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Failure Society of America, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance; pp. 1318–1368. (J Am Coll Cardiol). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linde C., Abraham W.T., Gold M.R. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients and in asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1834–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang A.S., Wells G.A., Talajic M. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young J.B., Abraham W.T., Smith A.L. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2685–2694. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindvall C., Chatterjee N.A., Chang Y. National Trends in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation. 2016;133:273–281. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marijon E., Leclercq C., Narayanan K. Causes-of-death analysis of patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy: an analysis of the CeRtiTuDe cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2767–2776. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoshiki H., Shimizu A., Mitsuhashi T. Trends and determinant factors in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy devices in Japan: analysis of the Japan cardiac device treatment registry database. J Arrhythm. 2016;32:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung E.S., Leon A.R., Tavazzi L. Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation. 2008;117:2608–2616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barsheshet A., Goldenberg I., Moss A.J. Response to preventive cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with ischaemic and nonischaemic cardiomyopathy in MADIT-CRT. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1622–1630. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasparini M., Mantica M., Galimberti P. Is the outcome of cardiac resynchronization therapy related to the underlying etiology? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:175–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St John Sutton M., Plappert T., Hilpisch K.E. Sustained reverse left ventricular structural remodeling with cardiac resynchronization at one year is a function of etiology: quantitative Doppler echocardiographic evidence from the Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation (MIRACLE) Circulation. 2006;113:266–272. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.520817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St John Sutton M., Ghio S., Plappert T. Cardiac resynchronization induces major structural and functional reverse remodeling in patients with New York Heart Association class I/II heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:1858–1865. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.818724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldenberg I., Moss A.J., Hall W.J. Predictors of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) Circulation. 2011;124:1527–1536. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruwald M.H., Solomon S.D., Foster E. Left ventricular ejection fraction normalization in cardiac resynchronization therapy and risk of ventricular arrhythmias and clinical outcomes: results from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) trial. Circulation. 2014;130:2278–2286. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleland J.G., Abraham W.T., Linde C. An individual patient meta-analysis of five randomized trials assessing the effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on morbidity and mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3547–3556. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witt C.T., Kronborg M.B., Nohr E.A. Adding the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator to cardiac resynchronization therapy is associated with improved long-term survival in ischaemic, but not in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2016;18:413–419. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutyifa V., Geller L., Bogyi P. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy with implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker on mortality in heart failure patients: results of a high-volume, single-centre experience. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1323–1330. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barra S., Providencia R., Tang A. Importance of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator back-up in cardiac resynchronization therapy recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002539. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moss A.J., Hall W.J., Cannom D.S. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss A.J., Zareba W., Hall W.J. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An Y., Ando K., Soga Y. Mortality and predictors of appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in Japanese patients with Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II criteria. J Arrhythm. 2017;33:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bansch D., Antz M., Boczor S. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: the Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT) Circulation. 2002;105:1453–1458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012350.99718.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bardy G.H., Lee K.L., Mark D.B. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadish A., Dyer A., Daubert J.P. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2151–2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kober L., Thune J.J., Nielsen J.C. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strickberger S.A., Hummel J.D., Bartlett T.G. Amiodarone versus implantable cardioverter-defibrillator:randomized trial in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia--AMIOVIRT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1707–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh J.P., Klein H.U., Huang D.T. Left ventricular lead position and clinical outcome in the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial-cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT-CRT) trial. Circulation. 2011;123:1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bleeker G.B., Kaandorp T.A., Lamb H.J. Effect of posterolateral scar tissue on clinical and echocardiographic improvement after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2006;113:969–976. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delgado V., van Bommel R.J., Bertini M. Relative merits of left ventricular dyssynchrony, left ventricular lead position, and myocardial scar to predict long-term survival of ischemic heart failure patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2011;123:70–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.945345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan F.Z., Virdee M.S., Palmer C.R. Targeted left ventricular lead placement to guide cardiac resynchronization therapy: the TARGET study: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1509–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saba S., Marek J., Schwartzman D. Echocardiography-guided left ventricular lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the Speckle Tracking Assisted Resynchronization Therapy for Electrode Region trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:427–434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abu Daya H., Alam M.B., Adelstein E. Echocardiography-guided left ventricular lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy in ischemic vs nonischemic cardiomyopathy patients. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu C.M., Chau E., Sanderson J.E. Tissue Doppler echocardiographic evidence of reverse remodeling and improved synchronicity by simultaneously delaying regional contraction after biventricular pacing therapy in heart failure. Circulation. 2002;105:438–445. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marsan N.A., Bleeker G.B., Van Bommel R.J. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with ischemic versus non-ischemic heart failure: differential effect of optimizing interventricular pacing interval. Am Heart J. 2009;158:769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forleo G.B., Santini L., Giammaria M. Multipoint pacing via a quadripolar left-ventricular lead: preliminary results from the Italian registry on multipoint left-ventricular pacing in cardiac resynchronization therapy (IRON-MPP) Europace. 2016 doi: 10.1093/europace/euw094. [May 17. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pappone C., Calovic Z., Vicedomini G. Improving cardiac resynchronization therapy response with multipoint left ventricular pacing: twelve-month follow-up study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1250–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zanon F., Marcantoni L., Baracca E. Optimization of left ventricular pacing site plus multipoint pacing improves remodeling and clinical response to cardiac resynchronization therapy at 1 year. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1644–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sohal M., Shetty A., Niederer S. Mechanistic insights into the benefits of multisite pacing in cardiac resynchronization therapy: the importance of electrical substrate and rate of left ventricular activation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2449–2457. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umar F., Taylor R.J., Stegemann B. Haemodynamic effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy using single-vein, three-pole, multipoint left ventricular pacing in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy and a left ventricular free wall scar: the MAESTRO study. Europace. 2016;18:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niederer S.A., Shetty A.K., Plank G. Biophysical modeling to simulate the response to multisite left ventricular stimulation using a quadripolar pacing lead. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35(2):204–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimizu A., Mitsuhashi T., Furushima H. Current status of cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillators and factors influencing its prognosis in Japan. J Arrhythm. 2013;29:168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu A., Nitta T., Kurita T. Current status of implantable defibrillator devices in patients with left ventricular dysfunction - The first report from the online registry database. J Arrhythm. 2008;24:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu A., Nitta T., Kurita T. Actual conditions of implantable defibrillator therapy over 5 years in Japan. J Arrhythm. 2012;28:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gold M.R., Daubert J.C., Abraham W.T. Implantable defibrillators improve survival in patients with mildly symptomatic heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis of the long-term follow-up of remodeling in systolic left ventricular dysfunction (REVERSE) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:1163–1168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schuchert A., Muto C., Maounis T. Lead complications, device infections, and clinical outcomes in the first year after implantation of cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacemaker. Europace. 2013;15:71–76. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morani G., Gasparini M., Zanon F. Cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator improves long-term survival compared with cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacemaker in patients with a class IA indication for cardiac resynchronization therapy: data from the Contak Italian Registry. Europace. 2013;15:1273–1279. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Looi K.L., Gajendragadkar P.R., Khan F.Z. Cardiac resynchronisation therapy: pacemaker versus internal cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Heart. 2014;100:794–799. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reitan C., Chaudhry U., Bakos Z. Long-term results of cardiac resynchronization therapy: a comparison between CRT-pacemakers versus primary prophylactic CRT-defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:758–767. doi: 10.1111/pace.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barra S., Looi K.L., Gajendragadkar P.R. Applicability of a risk score for prediction of the long-term benefit of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2016;18:1187–1193. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Munir M.B., Althouse A.D., Rijal S. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older cardiac resynchronization therapy recipients using a pacemaker versus a defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:730–734. doi: 10.1111/jce.12951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goldenberg I., Vyas A.K., Hall W.J. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]