Abstract

Background

HIV incidence among US young, black MSM (YBMSM) is high, and structural barriers (e.g. lack of health insurance) may limit access to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Research studies conducted with YBMSM must ensure access to the best available HIV prevention methods, including PrEP.

Methods

We implemented an optional, non-incentivized PrEP program in addition to standard HIV prevention services in a prospective, observational cohort of HIV-negative YBMSM in Atlanta, GA. Provider visits and lab costs were covered; participant insurance plans and/or the manufacturer assistance program were used to obtain drug. Factors associated with PrEP initiation were assessed with prevalence ratios and time to PrEP initiation with Kaplan-Meier methods.

Results

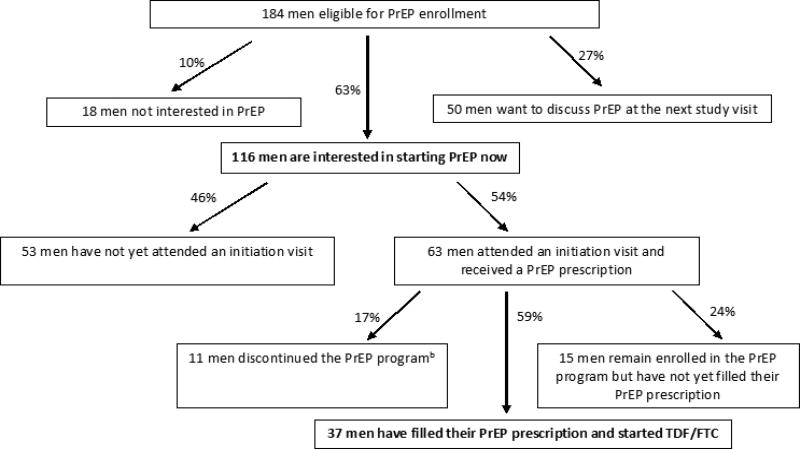

Of 192 enrolled YBMSM, 4% were taking PrEP at study entry. Of 184 eligible men, 63% indicated interest in initiating PrEP, 10% reported no PrEP interest, and 27% wanted to discuss PrEP again at a future study visit. Of 116 interested men, 46% have not attended a PrEP initiation appointment. Sixty-three men (63/184; 34%) initiated PrEP; 11/63 (17%) subsequently discontinued PrEP. The only factor associated with PrEP initiation was reported STI in the prior year (PR 1.50, 95%CI 1.002-2.25). Among interested men, median time to PrEP initiation was 16 weeks (95% CI 7–36).

Conclusions

Despite high levels of interest, PrEP uptake may be suboptimal among YBMSM in our cohort even with amelioration of structural barriers that can limit use. PrEP implementation as standard of HIV prevention care in observational studies is feasible; however, further research is needed to optimize uptake for YBMSM.

Keywords: PrEP uptake, PrEP interest, young black MSM, PrEP implementation, barriers, HIV prevention

Introduction

Alarming racial disparities in HIV incidence exist between black and white MSM in Atlanta, GA and throughout the US, with young black MSM (YBMSM) experiencing the highest incidence rates [1, 2]. Daily oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) effectively prevents HIV transmission among MSM [3–6]; however, a recent CDC study found that black MSM were half as likely to report PrEP use compared to white MSM [7]. In addition, PrEP uptake was slower in the South, with Atlanta MSM reporting 60% lower PrEP use compared to San Francisco MSM. We have previously shown how racial disparities in health insurance and healthcare access could lead to lower PrEP uptake for black MSM in Atlanta [8]. Therefore, effective PrEP implementation in this group requires innovative strategies to ensure those who may benefit from PrEP are aware of PrEP, educated about risks and benefits, and have adequate access to PrEP services.

There is a public health urgency for HIV research studies and prevention programs serving YBMSM to offer the best available HIV prevention services, including PrEP. Traditionally, ‘standard of HIV prevention care’ in research studies includes provision of risk reduction counseling, Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) counseling, free condoms, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) diagnosis and treatment referrals [9]. However, the field has struggled to incorporate PrEP as ‘standard of HIV prevention care’ given the significant financial and logistical hurdles associated with this costly medical intervention [9–11]. Some argue that research studies should be mandated to offer PrEP to everyone as it is an effective, FDA-approved HIV prevention intervention [11]. While there is a strong ethical obligation to reduce HIV risk among research participants, no formal guidance exists for inclusion of PrEP into research studies.

At a minimum, HIV prevention programs and research studies must reduce structural barriers that limit PrEP uptake for YBMSM. Prior studies have relied on external referrals for PrEP outside of the research study context [9]. A referral-based program may not fully address these barriers for YBMSM as many lack access to healthcare [8, 12–14]. Here, we describe the implementation of an optional PrEP program as an addition to a standard package of HIV prevention services in a currently enrolling, HIV/STI incidence cohort of YBMSM in Atlanta, GA. A detailed understanding of facilitators and barriers to PrEP uptake among YBMSM is necessary to inform the development of targeted interventions to promote PrEP uptake and adherence within this population. This implementation framework may serve as a guide for research studies wishing to offer PrEP for HIV prevention.

Methods

Primary study

The EleMENt study is an ongoing, prospective, observational cohort study designed to examine the partner-level and event-level relationships between substance use and HIV risk among YBMSM in Atlanta that began recruitment in June 2015. MSM are recruited via venue-day-time-space sampling and advertisements posted on Facebook, Grindr, and MARTA. HIV-negative MSM aged 16–29 years who report black race, non-Hispanic ethnicity, being male at birth, living in the Atlanta Metropolitan Statistical Area, and having ≥1 male sex partner in the previous 3 months are eligible for enrollment.

EleMENt study visits are conducted in 4-hour time blocks called ‘study events’ approximately 3–4 times weekly including nights and weekends at several locations (e.g. community based organizations, clinical research sites after hours, etc.) throughout metro-Atlanta. Study events are staffed by non-clinician EleMENt personnel with training in HIV testing and counseling, phlebotomy, and lab processing and as many as 20 participant visits are scheduled during an event. At visits, participants are tested for HIV using a rapid test, syphilis, and urethral and rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea. HIV-negative participants receive qualitative HIV nucleic-acid amplification testing (NAAT), as part of an acute HIV-infection detection protocol [15]. All participants receive comprehensive HIV/STI risk-reduction counseling which includes the provision of condoms and lubricant. Participants complete a computer-assisted self-interview questionnaire to assess demographics, HIV prevention behaviors including previous PrEP awareness and use, and HIV sexual risk factors. HIV-negative participants are followed prospectively with study visits at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after enrollment. Participants who test positive for HIV and/or STIs are linked by study staff to care and treatment services.

Optional PrEP Program

The EleMENt study was originally proposed and funded in 2012–2013, and its scientific objectives did not pertain to or include the provision of PrEP. In order to offer PrEP directly within the cohort without the need for external referral or navigation to PrEP services, we obtained supplemental funding for financial coverage of provider visits and lab costs. Men are not recruited for EleMENt based on PrEP interest or knowledge and recruitment materials do not include information about PrEP. All enrolled men are considered PrEP eligible irrespective of reported risk behavior and offered non-incentivized, daily oral TDF/FTC in addition to comprehensive HIV/STI risk-reduction counseling and condom provision as ‘standard of HIV prevention care’. Free transportation to all visits is available for all participants. Inclusion criteria for the PrEP program included negative HIV antibody and viral load testing, creatinine clearance ≥ 60 ml/min, negative Hepatitis B viral load testing, no medical contraindications, and willingness to adhere to daily oral dosing and attend monitoring visits every 3 months.

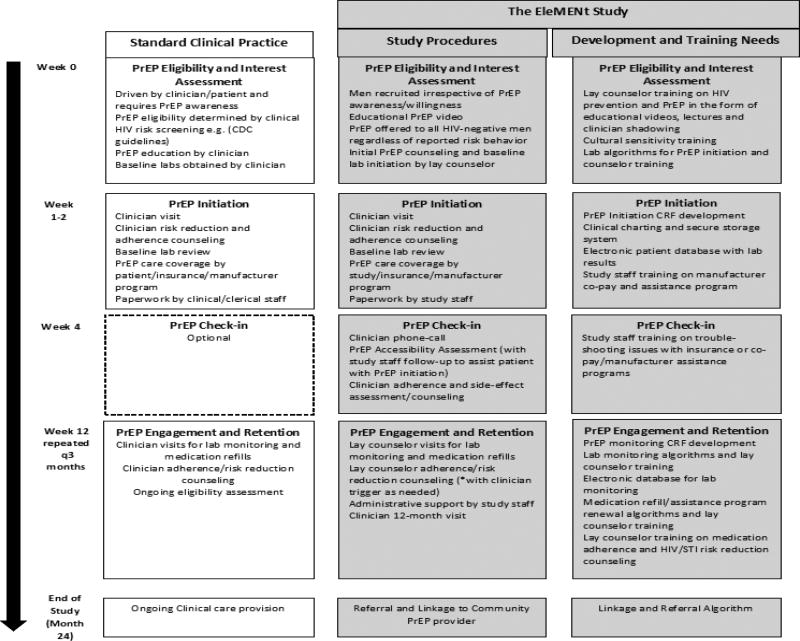

Figure 1 outlines the EleMENt PrEP program, differences from standard clinical care, and development needs for implementing a similar program. Initially, men are educated about PrEP by lay study counselors and watch a short video [16]. Participants are then asked to take a brief survey assessing reasons for PrEP interest and disinterest from a list of options based on prior PrEP willingness studies [17, 18] and whether they are interested in initiating PrEP now. Those interested in starting PrEP have additional labs drawn for qualitative Hepatitis B viral load and creatinine and scheduled to see a study clinician within 1–2 weeks for an initiation visit. PrEP initiation visits with a study clinician are offered at least weekly during a scheduled EleMENt study event and, for participants who are not able to attend a study event where PrEP is offered, EleMENt clinicians offer daytime office hours to facilitate these initiations. Same-day PrEP starts are offered on a limited basis when a clinician is available at a study event and time allows. Men who do not initiate PrEP are re-assessed for PrEP interest at each follow-up visit and can enroll in the PrEP program at any point.

Figure 1.

Framework for PrEP implementation in an observational, prospective cohort study of young black MSM in Atlanta, GA

Abbreviations. PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CRF, clinical research form; STI, sexually transmitted infection

At the PrEP initiation visit, all participants undergo rapid HIV testing, meet with a study clinician for adherence and risk reduction counseling, receive a prescription and keychain pillbox, and are invited to sign-up for medication reminders using free electronic apps and reminder services. Participants with health insurance use their insurance plan to pay for TDF/FTC and manufacturer copay cards are provided by the study to minimize associated prescription costs. Study staff provide assistance for uninsured men to enroll in the manufacturer patient assistance program (PAP) and receive TDF/FTC free of charge. One month following PrEP initiation, study clinicians phone participants to ensure that they have obtained TDF/FTC and perform an initial adherence and safety assessment.

Whenever possible, PrEP follow-up visits are incorporated into EleMENt study visits, however, additional non-incentivized visits are necessary for participants on PrEP due to the recommended 3-month follow-up schedule. At these visits, lay study staff perform the recommended lab monitoring, adherence and risk reduction counseling, assessment for side effects and management of prescription, co-pay card and patient assistance program (PAP) renewals. Participants are asked to complete a brief survey about their experiences taking PrEP. The study clinician reviews the results of these activities and responds to issues related to adherence, side effects and desire for PrEP discontinuation by following up with participants as needed. Men can enroll, withdraw, and re-enroll in the PrEP program at any time during study follow-up. Men who desire PrEP upon study termination/completion will be referred and linked to a community PrEP provider. Informed consent was obtained for all participants and the Institutional Review Board at Emory University approved study procedures.

Measures

Data on demographics, income, insurance status, healthcare usage, HIV risk factors, HIV testing behaviors and substance use were obtained from the EleMENt baseline survey. Men were defined as having a primary care provider (PCP) if they reported having a regular healthcare provider or receiving care in an on-campus health center within the past 12 months. Substance use was defined as the self-reported use of non-injection or injection drugs not prescribed by a provider in the previous 6 months. Reasons for PrEP interest and disinterest were obtained from the PrEP interest survey. PrEP initiation was defined as attendance at a PrEP initiation appointment; medication start was confirmed at the one-month clinician follow-up by participant self-report of the date they began taking the medication.

Statistical Analysis

Associations between baseline demographic and risk behavior variables with PrEP initiation were examined with unadjusted prevalence ratios (PRs). Reasons for PrEP interest and disinterest between PrEP initiators and non-initiators were compared with unadjusted Chi square tests. Cumulative probabilities of PrEP interest, initiation, and medication start were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Median time to PrEP interest and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the entire cohort, whereas median time to PrEP initiation was assessed among interested men; median time to TDF/FTC start was assessed among those who initiated. Participants were right-censored at the time of data analysis if these events had not been observed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and R Studio, version 1.0.44 [19].

Results

From July 2015 through December 2016, 192 HIV-negative men enrolled in the EleMENt study, 4% (8/192) of men were already taking PrEP upon study entry leaving 184 men eligible for EleMENt’s PrEP program (Table 1). The median age of the sample was 24 years (IQR 22, 26), most reported at least some college education, median annual income was $20,000/year, and over 50% had health insurance. Most identified as gay or homosexual and were not in a committed relationship. Nearly three-quarters of men reported substance use and condomless anal intercourse (CAI) in the 6 months prior to study enrollment. One quarter reported an STI diagnosis in the previous year and the majority reported an HIV test in the last 12 months. Approximately one-half had heard of PrEP previously.

Table 1.

Factors associated with PrEP initiation among young, black MSM in the EleMENt PrEP program.

| Characteristic | Total N=184 N (%) |

Initiated PrEP (n=63) n (%) |

Did not initiate PrEP (n=121) n (%) |

Unadjusted PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| <24y.o. | 77 (42) | 21 (27) | 56 (73) | 0.69 (0.45, 1.08) |

| ≥24 y.o. | 107 (58) | 42 (39) | 65 (61) | |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| High school or below | 55 (30) | 16 (29) | 39 (71) | 0.80 (0.50, 1.28) |

| At least some college | 129 (70) | 47 (36) | 82 (64) | |

|

| ||||

| Income | ||||

| <20,000 annually | 82 (45) | 27 (33) | 55 (67) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.39) |

| ≥20,000 annually | 102 (55) | 36 (36) | 65 (64) | |

|

| ||||

| Insurance | ||||

| Yes | 108 (59) | 34 (31) | 74 (69) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.23) |

| No | 76 (41) | 29 (38) | 47 (62) | |

|

| ||||

| Has a primary care provider | ||||

| Yes | 84 (46) | 29 (35) | 55 (65) | 1.02 (0.68, 1.52) |

| No | 100 (54) | 34 (34) | 66 (66) | |

|

| ||||

| Homeless | ||||

| Yes | 7 (4) | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | 0.41 (0.06, 2.58) |

| No | 177 (96) | 62 (35) | 115 (65) | |

|

| ||||

| Sexual identity | ||||

| Homosexual | 143 (78) | 53 (37) | 90 (63) | 1.52 (0.85, 2.73) |

| Bisexual/Other | 41 (22) | 10 (24) | 31 (76) | |

|

| ||||

| Relationship status | ||||

| Committed relationship | 46 (25) | 14 (30) | 32 (70) | 0.86 (0.52, 1.41) |

| Not in a committed relationship | 138 (75) | 49 (36) | 89 (64) | |

|

| ||||

| Substance abuse in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 132 (72) | 44 (33) | 88 (67) | 0.91 (0.59, 1.41) |

| No | 52 (28) | 19 (37) | 33 (63) | |

|

| ||||

| Jail in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 12 (7) | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 0.97 (0.42, 2.24) |

| No | 172 (93) | 59 (34) | 113 (66) | |

|

| ||||

| Any CAI in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 139 (76) | 52 (37) | 87 (63) | 1.53 (0.87, 2.68) |

| No | 45 (24) | 11 (24) | 34 (76) | |

|

| ||||

| CAI # of partners in the last 6 months | ||||

| 0–2 | 133 (77) | 44 (33) | 89 (67) | Ref |

| 3–5 | 27 (16) | 12 (44) | 15 (56) | 1.34 (0.82, 2.19) |

| 5+ | 13 (8) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) | 1.40 (0.73, 2.65) |

|

| ||||

| HIV-positive partner in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 16 (9) | 7 (44) | 9 (56) | 1.31 (0.72, 2.39) |

| No | 168 (91) | 56 (33) | 112 (67) | |

|

| ||||

| Exchange partner in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 11 (6) | 4 (36) | 7 (64) | 1.07 (0.47, 2.41) |

| No | 173 (94) | 59 (34) | 114 (66) | |

|

| ||||

| Reported STI in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 46 (25) | 21 (46) | 25 (54) | 1.50 (1.002, 2.25) |

| No | 138 (75) | 42 (30) | 96 (70) | |

|

| ||||

| HIV test in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 161 (88) | 58 (36) | 103 (64) | 1.66 (0.74, 3.72) |

| No | 23 (13) | 5 (22) | 18 (78) | |

|

| ||||

| Heard of PrEP previously | ||||

| Yes | 97 (53) | 38 (39) | 59 (61) | 1.36 (0.90, 2.07) |

| No | 87 (47) | 25 (29) | 62 (71) | |

Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; PR, Prevalence Ratio; PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; CAI, condomless anal intercourse; CAI #of partners, number of condomless anal intercourse partners; STI, sexually transmitted infection

PrEP was offered to all 184 eligible men. At the most recent study visit when data were censored for this analysis, 64% had expressed interest in initiating PrEP, 10% were not interested in PrEP, and 27% wanted to discuss PrEP at the next study visit (Figure 2). Of 116 interested men, 46% have not yet attended an initiation visit, despite repeated scheduling attempts for 36% of these men. Thirty-four percent of 184 eligible men received a prescription at a PrEP initiation visit, but only 20% (37/184) have started TDF/FTC to date. Ten percent (6/63) of PrEP initiations were same-day PrEP starts. Those who reported an STI diagnosis in the past year were 50% more likely to initiate PrEP (Table 1). The most popular reason for PrEP interest was the possibility of having sex without condoms in the future; the most common reason for disinterest was consistent condom use. Non-initiators were more likely to endorse the requirement for daily adherence as a reason for PrEP disinterest (Table 2).

Figure 2.

PrEP Interest and initiation among men eligible for the EleMENt PrEP programa (N=184)

Abbreviations. PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

aThese decisions are based on interest expressed at the most recent study follow-up visit when data were censored for this analysis; study enrollment and follow-up are ongoing.

bThis includes 2 men who started the medication and subsequently discontinued the program and 9 men who received a PrEP prescription at an initiation visit, but never filled it and decided to discontinue the program.

Table 2.

Reasons for PrEP Interest and Disinterest among men eligible for the EleMENt PrEP program.

| Reason | Initiated PrEP (N=55)a n (%) |

Did not initiate PrEP (N=86) n (%) |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I am at risk for HIV | 18 (33) | 27 (31) | 0.87 |

| I may have sex without condoms in the future | 32 (58) | 45 (52) | 0.5 |

| I always use condoms | 13 (24) | 32 (37) | 0.09 |

| I have a sex partner whose HIV status I do not know | 14 (25) | 14 (16) | 0.19 |

| I have a sex partner who is HIV positive | 10 (18) | 9 (10) | 0.2 |

| PrEP does not protect enough against HIV | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.89 |

| Condoms protect against HIV better than PrEP | 2 (4) | 3 (4) | 0.95 |

| I am worried about side effects | 12 (22) | 30 (35) | 0.1 |

| My community would be supportive | 11 (20) | 20 (23) | 0.66 |

| My friends would be supportive | 25 (45) | 28 (33) | 0.13 |

| My sexual partners would be supportive | 24 (44) | 30 (35) | 0.3 |

| I would be unhappy about taking a pill every day | 2 (3) | 19 (22) | 0.002 |

| I would be unhappy getting an HIV test every 3 months | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | N/A |

The PrEP interest survey was administered separately from the baseline survey and some men did not complete it.

Abbreviations. PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Ninety-two percent of men who initiated PrEP (58/63), compared to 74% (90/121) of men who did not initiate PrEP, met one or more CDC indicators for PrEP initiation (p=0.003; CAI in the prior 6 months, multiple sexual partners, STI diagnosis in the prior year, and having an HIV-positive partner [20]). Two-thirds of men who initiated PrEP had health insurance and used their plan and co-pay assistance to obtain TDF/FTC, and one-third were uninsured and enrolled in the PAP (data not shown). Three men who initiated PrEP and initially used their health insurance to obtain TDF/FTC lost their health insurance within 6 months of PrEP initiation and were subsequently enrolled in the PAP. During the one-month clinician assessment, 24/37 (65%) men reported missing zero PrEP doses in the preceding week. As of December 2016, 11 men discontinued PrEP. Nine men (81%) voluntarily withdrew from the PrEP program and reasons for withdrawal included no longer being interested (n=2), not at enough risk based on self-assessment after discussion with study staff (n=5), too busy to remain in the study (n=1) and moving away from Atlanta (n=1). Two men were administratively withdrawn due to PrEP non-adherence.

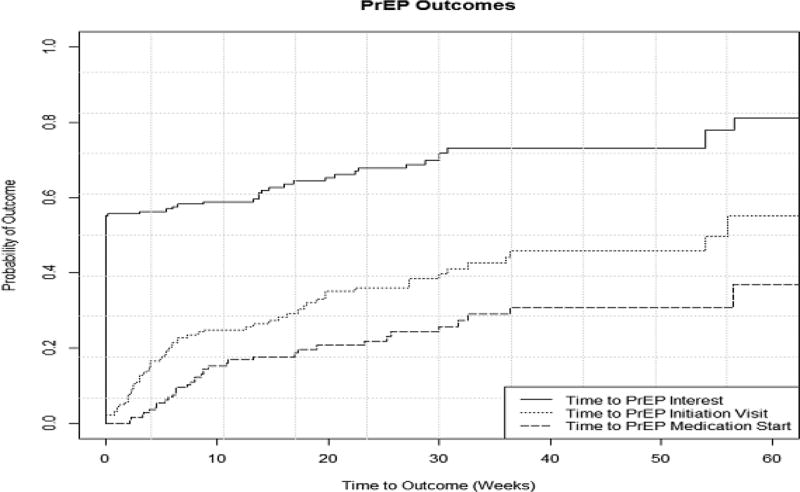

Kaplan-Meier cumulative probability estimates for PrEP interest, initiation, and medication start reveals that over 50% of the cohort reported interest in PrEP at the baseline study visit; however, there is a marked drop-off in subsequent initiation and medication start (Figure 3). Despite robust PrEP interest, median time to PrEP initiation was 16 weeks (95%CI 7–36) among interested men. Among those receiving a prescription, 24/63 (38%) men never started taking TDF/FTC including 15 men who remain enrolled in the PrEP program and 9 men who discontinued the program; median time to medication start was 3 weeks (95%CI 2–6).

Figure 3.

Time to PrEP Interest, initiation and medication start among men eligible for PrEP in the EleMENt program (N=184)

Abbreviations and Definitions. PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; PrEP initiation, attendance at an initiation visit; PrEP Medication start, confirmed prescription fill

Solid line: Time to PrEP interest for the entire cohort, Dotted Line: Time to PrEP initiation for the entire cohort, Dashed Line: Time to PrEP Medication start for the entire cohort

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that implementation of PrEP as standard of HIV prevention care in observational studies is feasible. Previous PrEP demonstration projects and clinical trials that have included PrEP utilized a full clinical staff including clinicians, lab technicians, social workers, and counselors devoted to PrEP education, initiation, and retention [12, 13, 21–23]. Several projects offered regular clinical hours allowing for “drop in” visits and also provided additional support services including counseling, meal/housing assistance, and leadership/job training courses [12, 21]. Notably, a few studies were incentivized and recruited individuals already interested in taking PrEP [13, 21, 23]. Other studies offered PrEP using a referral based system, and provided TDF/FTC free of charge [9]. Our study differs significantly in that our study recruitment materials did not contain information about PrEP, and we offered non-incentivized PrEP as standard of HIV prevention care to all enrolled YBMSM by task-shifting some clinical duties to trained study staff and use of participant health insurance plans and/or the manufacturer assistance programs to access TDF/FTC.

The decision to offer PrEP within EleMENt was guided by two core ethical principles: beneficence and social justice. Beneficence refers to the practice of assuring that participants receive the highest standard of care available in the research setting, and PrEP is considered by many to be standard of HIV prevention care as it is scientifically validated and FDA-approved [9, 11]. The principle of social justice refers to the equitable access of interventions that have the potential to reduce disparities affecting a particular health outcome [10]. Previous data have demonstrated racial disparities in PrEP use [7, 24], which may paradoxically worsen racial disparities in HIV infection. We believe that there is an ethical responsibility to optimize PrEP uptake in research studies conducted with YBMSM or other key populations at high risk of HIV acquisition. Given that significant structural barriers exist for YBMSM to access PrEP [8] and the low overall PrEP uptake in Atlanta [7], we offered direct access to PrEP for all enrollees within the context of our study.

Our study is the first to provide a framework for implementation of PrEP into observational prevention studies. We have outlined key differences between procedures in standard clinical practice and our cohort study, which include the use of lay study staff to initially introduce and educate about PrEP with the use of media tools, task shifting clinical duties to lay study staff, and the incorporation of PrEP visits into the existing study framework. However, this requires extensive staff training, protocol and database development, and consistent monitoring and adjustments for successful PrEP implementation. We encourage future prevention studies to consider offering PrEP using our model and provide guidance on required staffing needs for this service. In addition, uptake estimates from our study may be useful to inform study design and sample size for trials offering PrEP to YBMSM.

Resources to provide PrEP within the context of an observational cohort may serve as a significant barrier to implementation. Estimated costs/year of PrEP delivery within the clinical context are $10,000–11,000 per year with drug costs accounting for 85% of the cost [25]. Participants utilized manufacturer co-pay assistance and the PAP to reduce drug costs; however, significant staff effort (approximately 8–10 hours weekly) was required to counsel participants, navigate, monitor, and renew these mechanisms. Additional costs associated with clinician visits, though minimized in our study framework, and lab testing are also important budget considerations in planning future projects. Investigators and funding agencies will need to be cognizant of the additional resources necessary to include PrEP in research studies of high risk populations.

Although we found high PrEP interest among YBMSM in EleMENt, PrEP initiation (34%) and medication start (20%) was lower and may be suboptimal to significantly reduce HIV incidence in this population [26]. Previous studies have also shown similar discrepancies between PrEP interest and uptake among Black MSM [7] with overall low uptake reported (2.5–18%) [7, 24, 27–30]. In their ‘Motivational PrEP Cascade’ based on the Transtheoretical Model of Change, Parsons et al show that many MSM are lost in the pre-contemplative (unwilling to take PrEP or believe they were appropriate PrEP candidates) or contemplative (willing to take PrEP but without real plans to start) stages of behavior change [31]. Our baseline PrEP interest survey suggests that initial barriers to willingness may include self-assessed low risk behavior and the requirement for daily adherence, which is consistent with data from prior studies [17, 18]. However, our results also provide direct evidence of a critical barrier between willingness and uptake of PrEP, and further research is needed to develop interventions to improve progression from willingness to PrEP uptake among YBMSM.

In contrast to our design and findings, HPTN 073 was a PrEP demonstration project which reported 79% PrEP uptake among 226 black MSM using a client-centered care coordination counseling approach (C4) [21]. These results occurred in the context of an incentivized demonstration project with advertisement materials including information about PrEP. Men enrolled in EleMENt were recruited without regard to PrEP knowledge or willingness and were not incentivized to uptake PrEP. Of significant importance, only ½ of our cohort had heard of PrEP prior to enrollment. Our study therefore provides estimates that are more representative of “real-world” PrEP uptake among YBMSM and are notably higher than those cited by prior population-based studies [7, 24, 27–30]. This may be reflective of our intensive PrEP education efforts combined with the convenience of PrEP access and covered costs of PrEP provider visits and labs within the study. These data are a necessary first step to fully understand the motivators and barriers to PrEP use among YBMSM that may be experienced in clinical and public health settings and provide insight on key strategies to promote PrEP uptake within this group.

Men reporting an STI diagnosis in the prior year were 50% more likely to initiate PrEP. This is consistent with previous findings, in which higher-risk men were most likely to uptake PrEP [7, 27, 28]. Overall, 92% of men in the EleMENt study who initiated PrEP met CDC guidelines for considering MSM behaviorally eligible for PrEP. Prior studies have consistently shown risk-behavior screening to be less accurate when predicting HIV risk within communities with high HIV prevalence [2, 32, 33]. We have previously demonstrated how use of CDC PrEP eligibility guidelines would have missed 30% of HIV seroconverters in a high incidence cohort of Atlanta MSM [2, 34]. Given these observations, we decided to offer PrEP to all HIV-negative YBMSM in the EleMENt study regardless of reported risk. This has important implications when developing inclusion criteria for studies and programs offering PrEP to YBMSM and strongly encourages the consideration of local epidemiologic trends when identifying appropriate PrEP candidates.

This study may not be fully generalizable to other populations of YBMSM as our sample originates from a single city in the Southeastern US. Our lower PrEP uptake estimates as compared to data from other samples of BMSM (e.g. HPTN 073) may reflect the lack of use of the C4 intervention or other effective interventions to increase PrEP uptake in this group. We were also unable to consistently offer same-day PrEP starts and may have lost men to follow-up during the delay between expression of PrEP interest and scheduling of the initiation visit [35–37]. Lastly, our sample size is relatively small and we have limited follow-up time to report to date. Additional longitudinal analyses, including formal adherence and PrEP persistence estimates, and qualitative interviews, are ongoing and will be reported once study follow-up is complete in 2019.

Conclusions

We describe the first implementation of optional PrEP as standard of HIV prevention care in an observational study of YBMSM. We have provided a framework for PrEP integration into future HIV prevention studies and argue that there is an ethical obligation for research studies to provide this effective intervention to communities disproportionately affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In our study, PrEP uptake appears suboptimal among YBMSM despite high levels of PrEP interest and attempts to minimize structural barriers affecting PrEP access. Further research is needed to fully understand the factors that mediate the relationship between interest and uptake of PrEP among YBMSM.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the dedicated EleMENt study staff and participants who have contributed significantly to this work.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: R01DA038196 (PI: Sullivan/Rosenberg), K23AI108335 (PI: Kelley), and a supplement grant (PI: Kelley) to the Emory Center for AIDS Research P30 AI050409.

Footnotes

Conferences: This data was partially presented in oral abstract form (Session O-8, Abstract Number 90) at the 2017 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) on Wednesday, February 15th in Seattle, WA.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for any author.

References

- 1.Hess H, et al. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). Abstract 52. Boston, Massachusetts: Feb 22–25, 2016. Estimating the Lifetime Risk of a Diagnosis of HIV Infection in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black, white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):445–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu AY, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection Integrated With Municipal- and Community-Based Sexual Health Services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):75–84. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack S, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volk JE, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increasing Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1601–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoots BE, et al. Willingness to Take, Use of Indications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men-20 US Cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):672–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley CF, et al. Applying a PrEP Continuum of Care for Men Who Have Sex With Men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1590–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson L, et al. Testing the waters: Ethical considerations for including PrEP in a phase IIb HIV vaccine efficacy trial. Clin Trials. 2015;12(4):394–402. doi: 10.1177/1740774515579165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haire B, et al. Ethical considerations in determining standard of prevention packages for HIV prevention trials: examining PrEP. Dev World Bioeth. 2013;13(2):87–94. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugarman J, Mayer KH. Ethics and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S135–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182987787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daughtridge GW, et al. I Am Men’s Health: Generating Adherence to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Young Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(2):103–7. doi: 10.1177/2325957414555230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosek S, et al. IAS 2015: 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and Prevention 2015. Program Number: TUAC0204LB. Vancouver, Canada: Jul 18–22, 2015. An HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demonstration project and safety study for young men who have sex with men in the United States (ATN 110) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA. Enhancing PrEP Access for Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoenigl M, et al. Screening for acute HIV infection in community-based settings: Cost-effectiveness and impact on transmissions. J Infect. 2016;73(5):476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amico KR, Hosek S. “What is PrEP?”. Video animation available at http://whatisprep.org/

- 17.Rolle CP, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black and White men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. International Journal of STDS and AIDS. doi: 10.1177/0956462416675095. Article first published online: October 20, 2016 as DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416675095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Cohen SE, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Studio Team. Rstudio. [2015-11-09] 2013 RStudio: Integrated development for R. Available at https://www.rstudio.com.

- 20.United States Public Health Service. Pre-Exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – 2014. [Accessed 12 December 2016];A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf.

- 21.Wheeler DP, et al. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). Abstract Number: 883LB. Boston, Massachusetts: Feb 22–25, 2016. HPTN 073: PrEP Uptake and Use by Black Men Who Have Sex With Men in 3 US Cities. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus JL, et al. Successful Implementation of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis: Lessons Learned From Three Clinical Settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(2):116–24. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosek S, et al. AIDS. Abstract 10118. Durban, South Africa: Jul 18–22, 2016. An HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demonstration project and safety study for adolescent MSM ages 15–17 in the United States (ATN 113) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snowden JM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of users of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2014 in a cross-sectional survey: implications for disparities. Sex Transm Infect. 2016 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juusola JL, et al. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):541–50. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenness SM, et al. Impact of the Centers for Disease Control’s HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Guidelines for Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(12):1800–1807. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hood JE, et al. Dramatic increase in preexposure prophylaxis use among MSM in Washington state. AIDS. 2016;30(3):515–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer KH, et al. Early Adopters: Correlates of HIV Chemoprophylaxis Use in Recent Online Samples of US Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1489–98. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doblecki-Lewis S, et al. Healthcare Access and PrEP Continuation in San Francisco and Miami Following the U.S. PrEP Demo Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bush S, et al. ASM Microbe 2016 / ICAAC. Abstract 2651. Boston, MA: Jun 16–20, 2016. Racial Characteristics of FTC/TDF for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users in the US. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons JT, et al. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States: The Motivational PrEP Cascade. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldman MB. A critical literature review to identify possible causes of higher rates of HIV infection among young black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1206–21. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millett GA, et al. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. Aids. 2007;21(15):2083–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones J, Hoenigl M, Siegler A, Sullivan PS, Little S, Rosenberg E. Assessing the Performance of Three HIV Incidence Risk Scores in a Cohort of Black and White MSM in the South. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000596. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez LM, et al. Immediate start of hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006260.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westhoff C, et al. Initiation of oral contraceptives using a quick start compared with a conventional start: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1270–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000264550.41242.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards SM, et al. Initiation of oral contraceptives--start now! J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(5):432–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]