Abstract

Being the most common cause of dementia, AD is a polygenic and neurodegenerative disease. Complex and multiple factors have been shown to be involved in its pathogenesis, of which the genetics play an indispensable role. It is widely accepted that discovery of potential genes related to the pathogenesis of AD would be of great help for the understanding of neurodegeneration and thus further promote molecular diagnosis in clinic settings. Generally, AD could be clarified into two types according to the onset age, the early-onset AD (EOAD) and the late-onset AD (LOAD). Progresses made by genetic studies on both EOAD and LOAD are believed to be essential not only for the revolution of conventional ideas but also for the revelation of new pathological mechanisms underlying AD pathogenesis. Currently, albeit the genetics of LOAD is much less well-understood compared to EOAD due to its complicated and multifactorial essence, Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and next generation sequencing (NGS) approaches have identified dozens of novel genes that may provide insight mechanism of LOAD. In this review, we analyze functions of the genes and summarize the distinct pathological mechanisms of how these genes would be involved in the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, genetics, mechanism, GWASs, EOAD, LOAD

Introduction

Being the most common cause of dementia, AD is a polygenic and neurodegenerative disease, defined as the presence of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (Ramirez-Bermudez, 2012). Neuroinflammation, synaptic and neurotransmitter loss are also involved in the pathogenesis of AD (Huang and Mucke, 2012; Anand et al., 2014). Clinically, patients’ increasingly loss of memory and impairment of related cognitive functions is the main feature of AD, which can be further divided into two subtypes, the early onset and late-onset forms, based on the on-set age. (Reitz et al., 2011).

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is usually autosomal dominant inherited, constituting barely 1–2% of AD, with genes including amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) being regarded as major factors (Reitz et al., 2011; Alzheimer’s Association, 2015). Although, late-onset AD (LOAD) is epidemiologically more common compared to EOAD, it is much more complex genetically because of the involvement of genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) 𝜀4 allele is the first discovered genetic risk factor for LOAD (Liu et al., 2013). Thereafter, with the advent of the genome-wide association studies (GWASs), dozens of additional genes have been found as potential risk factors for LOAD. This long gene list has already included ABCA7, BIN1, CASS4, CD2AP, CD33, CELF1, CLU, CR1, DSG2, EPHA1, FERMT2, HLA-DRB5/DRB1, INPP5D, MEF2C, MS4A4/MS4A6E, NME8, PICALM, PTK2B, SLC24A4/RIN3, SORL1, ZCWPW1 (Harold et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2009; Seshadri et al., 2010; Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2017), with novel identified genes, such as TREM2 and PLD3 which might be involved in LOAD, continuously being added (Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013; Cruchaga et al., 2014). The discovery of these genes has facilitated our gaining of the in-depth knowledge of the signaling pathways participated in AD pathogenesis. In this review, we will analyze functions of these genes and summarize possible mechanisms of how these genes would be involved in the pathogenesis of AD.

Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (EOAD)

Amyloid β (Aβ) Metabolism

Highly penetrant mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, cause the autosomal dominant EOAD (Reitz et al., 2011; Alzheimer’s Association, 2015). Additionally, rare variants in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 (Cruchaga et al., 2012), and ADAM10 (Kim et al., 2009), have been listed as the risk factors for LOAD (Panza et al., 2012). These studies indicated that the disturbance of Aβ metabolism plays a central role in AD pathogenesis.

APP

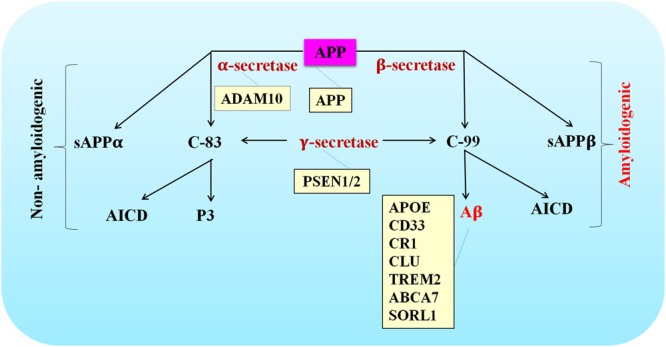

The APP gene is located on chromosome 21 and contains 19 exons for encoding a ubiquitously expressed type I transmembrane protein amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Goldgaber et al., 1987). The amyloidogenic pathway and non-amyloidogenic pathway are the two mutually exclusively pathways thought to be involved. The amyloidogenic pathway is defined as consecutive cleavage of APP by β- and γ-secretase. Aβ, soluble APP ectodomain (sAPPβ) and the APP intracellular domain (AICD) are the generated products (O’Brien and Wong, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Alternatively, α- and γ-secretase are engaged in the non-amyloidogenic pathway. Soluble APP ectodomain (sAPPα), p3-peptide and AICD are the end-products (O’Brien and Wong, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011).

Goate et al. (1991) first discovered a missense mutation in APP in AD pedigrees. At least 40 APP mutations are known to cause familial AD, mainly with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern1. Two recessive mutations in APP, E693Δ and A673V, were also identified to cause EOAD (Di Fede et al., 2009; Giaccone et al., 2010). Most of these mutations are found in the neighborhood of the Aβ domain (exons 16 and 17 of APP). The Swedish APP mutation (KM670/671NL) lies at the N-terminus of the Aβ domain and increases plasma Aβ levels by 2 to 3-fold by affecting the efficiency of β-secretase cleavage (Mullan et al., 1992). A sensible hypothesis is that excessive production of Aβ surpassing a certain threshold may cause AD. A supporting phenomenon is that Down syndrome patients, who have an extra copy of APP due to the 21 chromosome triplet, usually develop AD in their early life (Zekanowski and Wojda, 2009). Other APP mutations cluster at or after the C-terminal amino acids of the Aβ domain, such as the Flemish mutation (A692G) (Hendriks et al., 1992), Italian mutation (E693K) (Zou et al., 2014), Dutch mutation (E693Q) (Levy et al., 1990), Arctic mutation (E693G) (Kamino et al., 1992), and Iowa mutation (D694N) (Grabowski et al., 2001), Iranian mutation (T714A) (Pasalar et al., 2002), Australian mutation (T714I) (Kumar-Singh et al., 2000; Bornebroek et al., 2003), French mutation (V715M) (Ancolio et al., 1999; Bornebroek et al., 2003), German mutation (V715I) (Cruts et al., 2003), Florida mutation (I716V) (Eckman et al., 1997), and London mutation (V717I) (Goate et al., 1991). One thing these mutations may have in common is that they could produce more Aβ42 while decreasing the production of Aβ40 by affecting the cleaving activity of γ-secretase. Since Aβ42 is more amyloidogenic and easier to aggregate than Aβ40, patients with such APP mutations are more susceptible to AD, although their total amount of Aβ seems to be at the normal level. The Arctic mutation, E693G, affects neither the total Aβ amount nor the ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 (Kamino et al., 1992). However, this mutation increases the aggregation rate of the mutant peptide. These findings altogether indicate Aβ aggregation plays a key role in AD pathogenesis.

PSEN1 and PSEN2

PSEN1 and PSEN2 are located at chromosome 14q24.3 and 1q31-q42, respectively, encoding the presenilin 1 and presenilin 2 proteins, which are participated in the formation of γ-secretase complex (Steiner et al., 2008). In 1995, the first batch of mutations of the two genes were identified by researchers in EOAD families (Levy-Lahad et al., 1995; Rogaev et al., 1995; Sherrington et al., 1995). To date, 219 different PSEN1 mutations and 16 PSEN2 mutations have been identified in association with EOAD1. PSEN1 mutations account for 80% of the early-onset familial AD (EOFAD) cases, with PSEN2 mutations found in 5% EOFAD families1.

In the APP cleavage scenario, endoproteolysis at the C-terminal end followed by a second cleavage at the N-terminal end of the Aβ domain was executed by the γ-secretase, resulting in the generation of Aβ fragments (O’Brien and Wong, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Normally, most of the Aβ fragments are the less amyloidogenic Aβ40, Aβ42 occupies a small percentage. In contrast, the mutant γ-secretase would predominantly yield Aβ42 with small amount of Aβ40. Similar to what we have described for APP mutations, patients baring mutations of PSEN1 or PSEN2 might also be more susceptible to AD due to accumulation of the more amyloidogenic protein Aβ42 (Bagyinszky et al., 2014).

ADAM10

Recently, having worked through 1000 LOAD families, researchers found, Q170H and R181G, in 7 pedigrees of them (Kim et al., 2009). ADAM10 gene is located at chromosome 15q21.3, and encodes the AMAD10 protein, which is a member of the disintegrin and metalloprotease family (Saftig and Lichtenthaler, 2015). ADAM10 has been shown not only be able to readjust the constitutive activity of α-secretase, but to be responsible for accommodation of the regulatable activity of α-secretase in APP cleavage (Lammich et al., 1999; Lopez-Perez et al., 2001; Saftig and Lichtenthaler, 2015). Both Q170H and R181G mutations reside in the ADAM10 prodomain and significantly damage the cleavage ability of ADAM10 at the β-secretase site of APP both in vitro and in vivo (Kim et al., 2009). These findings further support the hypothesis that alteration of APP processing and Aβ generation is sufficient to cause AD.

Since Aβ peptides were discovered as a major pathological feature in AD brains, the hypothesis that excessive accumulation of misfolded β-sheet proteins causes AD started to gain public recognition. More and more evidence highlighted by genetic studies has been reported to support the central role that Aβ played in the pathogenesis of AD. For example, highly penetrant mutations have been identified as risk factors of AD in genes whose translation products are involved in APP processing and Aβ generation. Mutated genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of EOAD, while rare variants in ADAM10 may increase the risk of developing LOAD. Given Aβ production was affected by mutations or variants in these genes, these findings further strengthened causal relationship between Aβ generation and AD pathogenesis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of APP processing pathways that are either amyloidogenic or non-amyloidogenic. The site of action of various AD-associated mutations are listed in the orange colored boxes.

Late-Onset for Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD)

Cholesterol Metabolism

The APOE 𝜀4 allele has been identified as a main risk factor for LOAD (Michaelson, 2014). The encoded protein apolipoprotein E (ApoE) plays the role as a cholesterol carrier in the brain. This implicates the role of cholesterol metabolism pathway in AD pathogenesis. Additionally, GWAS studies have identified several genes that might be potential risk factors for LOAD, including ABCA7, CLU, and SORL1 (Harold et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2009; Hollingworth et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2017), which are involved in cholesterol metabolism.

APOE

The APOE is a gene situated in chromosome 19q13.2 encoding a protein containing 299 amino acids which is mainly expressed in the liver and brain (Siest et al., 1995). APOE is a key component of the lipoprotein complexes and plays a role in cholesterol metabolism by regulating cholesterol transport, delivery and distribution (Mahley and Rall, 2000; Lambert et al., 2009; Alonso Vilatela et al., 2012). 𝜀2, 𝜀3, and 𝜀4 are the are three common alleles of APOE in humans differed in sequence by two single nucleotide polymorphisms, rs429358 and rs7412 (amino-acid position 112 and 158) in exon 4 (Liu et al., 2013; Michaelson, 2014). APOE 𝜀3 allele is the most frequent isoform and accounts for 50–90% in all populations (Mahley and Rall, 2000; Alonso Vilatela et al., 2012). The percentage of individuals having the APOE 𝜀4 allele is approximately 50% in LOAD patients compared with 20–25% in controls (Alonso Vilatela et al., 2012; Michaelson, 2014). So far APOE 𝜀4 is the most well-established genetic risk factor for both sporadic LOAD and familial AD in different populations (Harwood et al., 1999; Quiroga et al., 1999; Evans et al., 2000). Compared with controls having no 𝜀4 alleles, the risk of AD is 4 times higher when subjects bearing one copy of the 𝜀4 allele, and 12 times higher with two copies (Alonso Vilatela et al., 2012). Conversely, the lower prevalence of the 𝜀2 allele in AD individuals compared with controls implicates its protective role in AD (Alonso Vilatela et al., 2012; Michaelson, 2014). In addition, the APOE 𝜀4 allele can affect clinical diagnosis of AD by influencing MRI features except white matter lesion volume (Biffi et al., 2010).

The mechanism of APOE increasing AD risk is not well known. The different APOE isoforms have different effects on Aβ aggregation and clearance in AD pathogenesis (Castellano et al., 2011). Clearance of Aβ in the brain depends on coordination with APOE (Wollmer, 2010; Verghese et al., 2013). Specifically, types of APOE that Aβ bound to affect its transportation efficiency. Aβ being bound to APOE2 or APOE3 results in better efficiency compared to APOE4 (Wollmer, 2010). APOE4 can also participate in other pathways, such as neuronal glucose hypometabolism, mitochondrial abnormalities and oxidative stress, by which play an important role in AD pathogenesis (Liu et al., 2013; Huang and Mahley, 2014).

ABCA7

ABCA7 is a gene situated in chromosome 19p13.3 encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 (ABCA7) which is a member of the ABC superfamily (Kim et al., 2006). The protein is highly expressed in the brain and functions as a transporter in the biogenesis of HDL by working together with cellular lipid and helical apolipoproteins (Tanaka et al., 2011). Data from several GWAS studies indicate ABCA7 is a genetic risk factor for LOAD (Hollingworth et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013). According to a meta-analysis published on the AlzGene website in April, 20112, a positive association between ABCA7 rs3764650 and AD was found in total 31011 cases and 48354 controls in all populations. Additionally, several other genetic studies further confirmed the relevance between ABCA7 SNPs and methylation changes with AD (Yu et al., 2015).

Loss of ABCA7 in mice is not embryonic lethal, suggesting that ABCA7 is not essential (Kim et al., 2005). However, loss of ABCA7 in mice seems to impair the ability of bone marrow-derived macrophages to uptake oliomeric Aβ. A recent study further showed that crossing between ABCA7-deficient and transgenic amyloidogenic mice would double the insoluble Aβ levels and amyloid plaques in the brains of their progenies compared with controls (Li et al., 2015). These findings indicate that ABCA7 may participate in the regulation of Aβ homoeostasis in the brain.

CLU

The CLU gene is located at 8p21.1 and encodes a multifunctional chaperone protein, clusterin (Wong et al., 1994), which has been implicated in AD for the past 20 years (May et al., 1990; Oda et al., 1994; Calero et al., 2000). Clusterin, also meaning as apolipoprotein J (APOJ), is one of the major apolipoproteins, with upregulated expression in the cortex and hippocampus of AD patients (May et al., 1990; Oda et al., 1994; Pasinetti, 1996). In terms of cholesterol metabolism, clusterin takes part in reverse cholesterol transport as a component of HDL particles (Wollmer, 2010). In addition, clusterin levels have been shown to be elevated in AD plasma (Jones et al., 2010). Meta analysis show that SNPs rs11136000, rs2279590, rs7012010, rs7982, and rs9331888 in CLU are protective genetic factors in LOAD3. However, the reproducibility of these associations was questionable when ethnic factors were taken into account (Li et al., 2011; Klimkowicz-Mrowiec et al., 2013; Tan L. et al., 2013). Genetic heterogeneity may be the underlying cause at play. Clusterin has several functions similar to apolipoprotein E and there are some interactions between them (Wollmer, 2010). Clusterin can also bind Aβ and modulate Aβ metabolism which are influenced by the molar ratios of clusterin and Aβ. (Yerbury et al., 2007; Aiyaz et al., 2012). In addition, clusterin participates in cell apoptosis and complement regulation, lipid transport and membrane protection, thus plays a role in AD pathogenesis (Bell et al., 2007; Nuutinen et al., 2009; Wollmer, 2010; Martin et al., 2014).

SORL1

The SORL1 gene, also known as SORLA1 or LR11, is situated in 11q23.2–q24.2 and encodes the sortilin-related receptor containing LDL receptor class A repeats (Wollmer, 2010). SORL1 is a member of the VPS10 receptors family which functions by binding lipoproteins including APOE-containing particles, thus mediating endocytotic uptake (Willnow et al., 2008; Wollmer, 2010). The decreased SORL1 expression was found to be associated with AD in 10 years ago (Scherzer et al., 2004). Utilizing microarray screening and immunohistochemistry, researchers showed that AD patients tend to have moderately lower SORL1 DNA transcription levels in their lymphoblast and significantly decreased SORL1 protein level in their brains, especially the pyramidal neurons and frontal cortex (Scherzer et al., 2004). The suppression of SORL1 expression can lead to overexpression of Aβ and an increased risk of AD (Andersen et al., 2005; Offe et al., 2006; Vardarajan et al., 2012). In addition, two specific clusters of SNPs in SORL1 were identified to have an association with familial and sporadic AD (Bettens et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008; Kimura et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2009; Sweet et al., 2010; Reitz, 2013).

Since cholesterol is an integral component of biomembrane, due to the key roles of biomembrane in transportation and cleavage of APP, aggregation of Aβ, and Aβ toxicity, it is entirely possible that abnormality of cholesterol metabolism may have an impact on multiple links of the pathogenic signaling pathways of AD. Epidemiological studies showed that high cholesterol levels in mid-life may lead to dementia in later life. Cholesterol-lowering reagents, such as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzym, which is a reductase inhibitor known as statins, may reduce the likelihood of developing dementia. The APOE plays an indispensable role in cholesterol transport of the brain. As a risk factor of AD, the APOE gene bridges the gap between AD pathogenesis and cholesterol metabolism. This bridge was further reinforced when recent GWAS studies showed a new batch of genes, including ABCA7, CLU, and SORL1, may increase the risk of LOAD by affecting cholesterol metabolism.

Cell Adhesion and Endocytosis

Endocytosis is central to AD because APP, Aβ, and APOE are all internalized through the endolysosomal trafficking pathway, and alterations in APP trafficking through intracellular compartments can directly influence APP proteolytical cleavage (Huang and Mucke, 2012). Several genes identified in GWAS-LOAD studies are associated with cell adhesion and endocytosis, including BIN1, CD2AP, EPHA1, PICALM, and SORL1 (Harold et al., 2009; Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015).

BIN1

The Bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1) is located on chromosome 2q14.3 and has 20 exons which can be spliced into multiple isoforms (Panza et al., 2012; Prokic et al., 2014). BIN1 isoforms, such as isoforms 1–6, are mainly expressed in the brain, in neurons (Prokic et al., 2014). BIN1 was initially found as a tumor suppressor with a MYC-interacting domain, a C-terminal SH3 domain, and an N-terminal BAR (Bin1/Amphiphysin/RVS167) domain (Sakamuro et al., 1996). Processing diverse cellular functions, BIN1 is a key regulator within a cell. From endocytosis to membrane recycling, from cell cycle progression to apoptosis, we can see its roles (Prokic et al., 2014). Cytoskeleton regulation and DNA repair are also involved (Prokic et al., 2014).

BIN1 was regarded as the second most important genetic risk factor for LOAD after the APOE 𝜀4.4 Common variants in the BIN1 gene are initially identified to be associated with AD in GWAS-LOAD studies (Harold et al., 2009; Seshadri et al., 2010; Naj et al., 2011). The main associated SNPs are in the 5′ region, including the most significant SNPs rs744373 and rs7561528, which are located approximately 30 and 25 kb from the BIN1 coding region, respectively (Harold et al., 2009; Seshadri et al., 2010; Naj et al., 2011; Karch and Goate, 2015). BIN1 can interact with cytoplasmic linker protein 170 (CLIP-170), a microtubule-associated protein (Meunier et al., 2009). Genetic variants in BIN1 were associated with magnetic resonance imaging measures associated with AD including entorhinal cortex thickness and temporal pole cortex thickness (Biffi et al., 2010). Recent studies have demonstrated the physical interaction between BIN1 and tau protein in human neuroblastoma cells overexpressing these two proteins and in wild type mouse brain homogenates (Kingwell, 2013). Besides its potential effects on tau pathology, BIN1 has also been identified as a regulator of endocytosis and trafficking, immunity and inflammation of the brain, transient calcium potentials, and apoptosis (Tan M.S. et al., 2013).

CD2AP

CD2AP (CD2-associated protein) is located on chromosome 6q12. CD2AP is first discovered as a ligand protein interacting with the T-cell-adhesion protein CD2 (Dustin et al., 1998; Wolf and Stahl, 2003). CD2AP is widely expressed, primarily in epithelial and lymphoid cells (Shih et al., 2001). It consists of three N-terminal SH3 domains followed by a proline rich domain (PRD) and a C-terminal coiled-coil domain (Shih et al., 2001). CD2AP has been shown to be involved in signal transduction, podocyte homeostasis and dynamic actin remodeling (Ma et al., 2010). The protein also takes part in membrane trafficking during endocytosis and cytokinesis (Ma et al., 2010). SNPs rs9296559 and rs9349407 in CD2AP are associated with increased LOAD risk (Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012). Like PICALM, the homologs of CD2AP have shown to be able to suppress the Aβ toxicity in yeast and Caenorhabditis elegans (Treusch et al., 2011). In addition, RNA interference-mediated disruption of cindr, the fly ortholog of CD2AP, enhances Tau toxicity in Drosophila (Shulman et al., 2014).

EPHA1

EPHA1 (EPH Receptor A1) is a gene situated in chromosome 7q34. The encoded EPH Receptor A1 protein is a member of the ephrin family of tyrosine kinase receptors. Proteins of this family modulate cell adhesion by interacting with ephrin ligands on adjacent cells (Sharfe et al., 2008). Ephrin receptors also plays a role in regulating synapse formation and synaptic plasticity (Lai and Ip, 2009). In addition, these ephrin receptors participate in regulating apoptosis of neural progenitor cells (Kullander and Klein, 2002; Kim et al., 2008). The SNP rs11771145 was identified as a protective genetic factor for LOAD (Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012). Albeit some research has been made on the function of ephrin receptors, knowledge on the EPHA1 gene and its role in AD etiology remains to be lacking.

PICALM

PICALM (phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein) is a gene situated in 11q14.2, encoding a clathrin adaptor protein which is produced as two main isoforms with 19–21 exons and 7 different known splice variants. PICALM was first cloned as a gene fused with AF10 in acute myeloid leukemia (Dreyling et al., 1996; Ando et al., 2013). Whereas PICALM is ubiquitously expressed, its homolog AP180 is exclusively expressed in neuron (Yao et al., 2005). PICALM is implicated in clathrin mediated endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of the synaptic vesicle protein VAMP2 which is necessary for neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic membrane (Tebar et al., 1999; Schnetz-Boutaud et al., 2012). Two SNPs (rs3851179 and rs541458) 5′ to the PICALM gene were identified to be associated with reduced LOAD risk in Caucasians (Harold et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2013). However, the reproducibility of these results was questionable when ethnic factor was taken into account (Li et al., 2011; Klimkowicz-Mrowiec et al., 2013; Tan L. et al., 2013). Genetic heterogeneity may be the underlying reason at play. In addition, AD patients with PICALM mutants may manifest different imaging features on MRI (Biffi et al., 2010). Hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortex thickness are the two measures affected most prominently (Biffi et al., 2010). Till now, the role of PICALM in AD etiology has not been known. The YAP1802, ortholog of PICALM, was found as a modifier of Aβ toxicity in a genome-wide screen in yeast (Treusch et al., 2011; Ando et al., 2013). PICALM was also shown to have a protective role for C. elegans and rat cortical neurons against the toxicity of oligomeric Aβ (Treusch et al., 2011). Another finding was that along with adaptor protein 2 (AP2) and APP-CTF, PICALM would be targeted to the autophagosomes to take part in the clearance of APP-CTF (Tian et al., 2013). In other words, PICALM may have a functional role in the clearance of Aβ via autophagy (Tian et al., 2013). In addition, PICALM displayed a specifically co-localization with neurofibrillary tangles in AD cases, suggesting that PICALM may participate in AD tau pathology (Ando et al., 2013).

Endocytosis is an active transportation mechanism to engulf molecules into a cell via vesicles formed by the cell membrane. It is the basis of various neuronal physiological functions, including synaptic vesicle transport and neurotransmitter release. The transportation and amyloidogenic cleavage of APP are interacting with the endocytosis pathway within cells. Thus, abnormal alterations in endocytosis may contribute to AD pathogenesis. Based on this hypothesis, SNPs in genes related to cell adhesion and endocytosis, such as BIN1, CD2AP, EPHA1, PICALM, and SORL1 are very likely to be involved in AD pathogenesis.

Immune Response

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of AD (Heneka et al., 2015). Solid evidence have proven the activation of inflammatory pathways in AD pathogenesis (Heneka et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Common variants in ABCA7, CD33, CLU, CR1, EPHA1, HLA-DRB5/DRB1, INPP5D, MEF2C, and MS4A, have been found to be associated with immune responses in recent GWAS studies (Harold et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2009; Seshadri et al., 2010; Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013). Additionally, rare coding variants in TREM2 gene related to the immune response were identified to increase risk of AD in LOAD (Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013).

CD33

CD33 is located on chromosome 19q13.3 and encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein cluster of differentiation 33 (CD33) (Zhang et al., 2014). CD33, which belongs to the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) family, bears molecular features of immune cell surface receptors that could trigger immune cell–cell interactions (von Gunten and Bochner, 2008). Studies showed that the expression of CD33 was increased in AD brains (Karch et al., 2012). The rs3865444 in CD33 was reported to be linked to a lowered LOAD risk (Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011). The rs3865444 A allele is associated with the decreased overall CD33 expression and an increased proportion of the CD33 isoform lacking exon 2 (Malik et al., 2013). The exon 2 in CD33 codes the IgV domain which mediates Siglecs family members binding to sialic acid, resulting in inhibition of phagocytosis (Villegas-Llerena et al., 2016). Loss of exon2 of CD33 in microglia abolishes the inhibitory effect of Aβ phagocytosis (Malik et al., 2013). In the context of the rs3865444 risk allele, there are increased cell surface expression of CD33 in monocytes, decreased internalization of Aβ42 accumulation in neuritic and fibrillar amyloid pathology, and more microglias activated (Bradshaw et al., 2013). Thus, CD33 may play an important role in Aβ clearance mediated by microglia in AD brain.

CR1

CR1 (Complement receptor 1) is located on chromosome 1q32 and encodes a multifunctional glycoprotein, expressed on microglia and blood cells such as erythrocytes (Villegas-Llerena et al., 2016). CR1 is a cell surface receptor that has binding sites for complement factors C3b and C4b. It participates in the clearance of immune complexes and regulates complement activation (Dunkelberger and Song, 2010). Two SNPs (rs6656401 and rs3818361) in CR1 have been found to be associated with LOAD risk in most Caucasians (Lambert et al., 2009). These associations could not be reproduced in other ethnic groups including African American, Israeli-Arab, Caribbean Hispanic, and Polish individuals due to the genetic heterogeneity (Li et al., 2011; Klimkowicz-Mrowiec et al., 2013; Tan L. et al., 2013). Genetic variants in CR1 can affect magnetic resonance imaging measures associated with AD such as entorhinal cortex thickness (Biffi et al., 2010). The exact function of CR1 in AD pathogenesis remains to be elusive. Since Aβ oligomers can bind C3b, some researchers postulated that CR1 may take part in the clearance of Aβ (Crehan et al., 2012).

HLA-DRB5/DRB1

The HLA-DRB5/DRB1 locus is a highly polymorphic region located on chromosome 6, encoding a member of the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), which is involved in the immune response and histocompatibility (Trowsdale and Knight, 2013; Villegas-Llerena et al., 2016). Recently, HLA-DRB5/DRB1 has been shown to be associated with multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease (PD) (International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium et al., 2011; International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium et al., 2011). Although PD and AD have distinct etiologies, they are both characterized by neurodegeneration resulting from abnormal protein aggregation. Therefore, it is a distinct possibility that HLA genes may play a similar role in both PD and AD through regulating inflammatory responses.

INPP5D

The INPP5D gene is a gene situated in chromosome 2q37.1, encoding a 145 kD protein which is a member of the inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5) family, also known as SH2 domain containing inositol-50-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) (Arijs et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). INPP5D is expressed predominantly in the hematopoietic cells (Hazen et al., 2009; Arijs et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). On the cell membrane, the protein takes part in various signaling pathways by hydrolyzing the 5′ phosphate from phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate and inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate (Scharenberg et al., 1998). Also, INPP5D plays as a negative regulator in B cell proliferation, chemotaxis and activation, as well as IgE- or IgE + Ag-induced inflammatory cytokine release from mast cells (Sly et al., 2003, 2007; Zhang et al., 2015). More studies are needed to understand the mechanism of how SHIP regulates the immune response and inflammation in the brain.

MEF2C

MEF2C protein is widely expressed and belongs to the MADS box transcription enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) family of transcription factors. The MEF2C gene is located on chromosome 5q14.3. It has been reported that MEF2 acts as a central transcriptional component of the innate immune response in the adult fly (Clark et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that MEF2C is involved in the inflammatory process in AD brains.

MS4A

The MS4A locus is located on chromosome 11 and contains at least five genes implicated in immune modulation (Villegas-Llerena et al., 2016). The discovery of the MS4A family owes to their homology to CD20, a B-lymphocyte cell surface molecule. Members of the MS4A family, including MS4A6A, are factors affecting AD pathology (Proitsi et al., 2014). Variations in proxies of rs670139 can increase AD risk (Allen et al., 2012).

TREM2

The TREM2 gene maps to chromosome 6p21.1, encoding Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2). TREM2 is mainly expressed on myeloid cells (Colonna, 2003; Jin et al., 2014). In the brain, TREM2 is primarily expressed on microglia (Lue et al., 2015). TREM2 takes part in inflammatory responses regulation (Rohn, 2013).

Homozygous mutations in TREM2 gene cause Nasu–Hakola disease, characterized by early onset frontotemporal-like dementia and bone involvement (Klunemann et al., 2005). In addition, some families with FTD-like dementia with leukodystrophy but without bone involvement have homozygous TREM2 mutations (Guerreiro et al., 2013). Recently, rare variants of the TREM2 gene have been identified to increase susceptibility to LOAD with an odds ratio similar to that of APOE 𝜀4 (Boutajangout and Wisniewski, 2013). rs75932628 is the most common variant in TREM2 polymorphism. It replaces Arginine 47 with Histidine and causes a 3-fold increase in the susceptibility to LOAD (Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). The status of TREM2 as a major LOAD risk locus was further strengthened by the odds ratio of 3.4 reported in a meta analysis (Guerreiro et al., 2013). The exact functions of TREM2 are not well understood. TREM2 may affect AD pathology through regulating phagocytosis (Hickman and El Khoury, 2014). The expression levels of TREM2 are upregulated in microglia found at the border of amyloid plaque deposits in transgenic AD mice (Lue et al., 2015). Moreover, there was a positive correlation between TREM2 expression and the phagocytic clearance of Aβ in APP transgenic mice (Lue et al., 2015).

Increasing evidence suggests the activation of inflammatory pathways in AD pathogenesis. GWAS suggests that several genes (ABCA7, CD33, CLU, CR1, EPHA1, HLA-DRB5/DRB1, INPP5D, MEF2C, and MS4A) regulating clearance of misfolded proteins mediated by glia and the inflammatory reaction could increase the risk of AD in LOAD. Furthermore, a rare variant of the TREM2 gene, with an odds ratio similar to that of APOE 𝜀4, was recently identified to be able to increase patients’ susceptibility to LOAD. These results together argue for the point that neuroinflammation is associated with AD pathogenesis. Although there is a lack of understanding how inflammation in AD is affected by these genes, the discovery of them have broadened our knowledge scope of AD and may expedite the unraveling of new therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of AD.

Tau Metabolism

The microtubule-associated protein tau is integral to the pathogenesis of AD. Rare mutations in the MAPT gene cause familial dementia syndromes (Lee and Leugers, 2012). GWAS studies have identified several genes that might be potential risk factors for LOAD, including BIN1, CD2AP, CELF1, FERMT2 and PICALM, which are involved in modulating tau neurotoxicity (Harold et al., 2009; Seshadri et al., 2010; Hollingworth et al., 2011; Naj et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013).

CELF1

The CELF1 gene is located on chromosome 11p11.2 and encodes the CUGBP and Elav-like family member 1 protein (CELF1). Members of the CELF protein family regulate alternative splicing, editing, and translation of mRNA (Wagnon et al., 2012). CELF1 gene may have a role in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) because of its interactions with the dystrophia myotonica-protein kinase (DMPK) gene (Roberts et al., 1997). In addition, overexpression of CELF1 suppressed the neurodegenerative eye phenotype in a transgenic fly model of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) (Sofola et al., 2007). The CELF1 protein modulates rCGG-mediated toxicity via a specific interaction with hnRNP A2/B1 (Sofola et al., 2007). Like FERMT2, RNA interference-mediated disruption of aret, the fly ortholog of CELF1, enhances Tau toxicity in a Drosophila model of AD (Shulman et al., 2014).

FERMT2

The FERMT2 (Fermitin Family Member 2) gene is located on chromosome 14q22 and is also known as mitogen-inducible gene 2 (MIG2) or kindlin 2 (KIND2) (Siegel et al., 2003). FERMT2 is ubiquitously expressed in mammalian cells and functions as a kind of cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) structures (Tu et al., 2003). A recent research validated the association of FERMT2 with AD risk by using a Drosophila model (Shulman et al., 2014). RNA interference-mediated disruption of FERMT2 homologs enhances Tau toxicity in Drosophila indicates these associations (Shulman et al., 2014).

Comprising of hyper-phosphorylated and aggregated tau protein, NFTs are one of the major pathological signatures of the AD brain. The neurotoxicity of Tau plays a central role in AD pathogenesis by affecting Aβ metabolism. It has been shown that there was a causal relationship between certain mutations of either APP or MAPT and familial dementia syndromes. As more and more genes related to tau neurotoxicity were identified as risk genes of AD, hopefully the molecular basis between Tau toxicity and AD would gradually become clear.

Perspectives

Genome-wide association studies is a powerful tool in identifying putative genetic risk factors. To date, more than 20 genetic variants have been identified as risk factors of AD. There is no gainsaying that GWAS helps us find novel perspectives on the pathogenesis of AD. However, there are still some limitations to be scrutinized. Firstly, some of these AD-associated variants are too rare or too weak to be used as prognostic predictors, which to some extent confound the integration of potential pathophysiological pathways of AD. On the contrary, whole exome sequencing has also discovered rare variants, such as TREM2 variants, whose odds ratios are comparable to that of APOE 𝜀4 in terms of increasing the risk of AD. Therefore, the range of these variants seems to be overly wide, which may have made it difficult for us to form a coherent and integrated theory. Moreover, although both SNPs with minor allele frequency down to 1% and novel functional exonic variants have been incorporated into the latest version of GWAS arrays, the detection would still be problematic when it comes to variants not tagged by the known SNPs or some extremely rare structural variants whose minor allele frequency are less than 1%. However, the role of such rare and structural variants should not be negligible in complex disease like AD. Therefore, ongoing and future large-scale next-generation whole exome or whole genome sequencing techniques need to address the issues aforementioned to accurately target causative variants in regions identified by GWAS. For only truly causative variants could yield meaningful functional studies to dissect molecular pathways in AD pathogenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Potential mechanisms of AD genes.

| Gene | SNP | Chromosome position | Protein | EOAD/ LOAD | Proposed function | Implicated pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA7 | rs3764650 rs4147929 | 19p13.3 | ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 | LOAD | Lipid homeostasis | Cholesterol metabolism; immune response |

| ADAM10 | rs61751103 rs145518263 | 15q21.3 | A disintegrin and metalloprotease family, AMAD10 | LOAD | Proteolytic cleavage of integral membrane proteins | Aβ metabolism |

| APOE | rs429358 rs7412 | 19q13.2 | Apolipoprotein E | LOAD | Mediates binding, internalization, and catabolism of lipoproteins | Cholesterol metabolism |

| APP | – | 21q21.3 | Amyloid precursor protein | EOAD | Neurite outgrowth, adhesion, and axonogenesis | Aβ metabolism |

| BIN1 | rs744373 rs7561528 | 2q14 | Bridging Integrator 1 | LOAD | Regulation of endocytosis of synaptic vesicles | Cell adhesion and endocytosis; tau metabolism |

| CASS4 | rs7274581 | 20q13.31 | Cas scaffolding protein family member 4 | LOAD | Docking protein in tyrosine-kinase signaling involved in cell adhesion and spreading | Cytoskeleton and axonal transport |

| CD2AP | rs9296559 rs9349407 | 6p12 | CD2-associated protein | LOAD | Scaffold molecule regulating actin cytoskeleton | Cell adhesion and endocytosis; tau metabolism |

| CD33 | rs3865444 | 19q13.3 | Cluster of differentiation 33 | LOAD | Mediates sialic acid-dependent binding to cells | Immune response |

| CELF1 | rs10838725 | 11p11 | CUGBP and Elav-like family member 1 | LOAD | Regulates pre-mRNA splicing | Tau metabolism |

| CLU | rs11136000, rs2279590, rs7012010, rs7982, rs9331888 | 8p21-p12 | Clusterin | LOAD | Chaperone; regulation of cell proliferation | Cholesterol metabolism Immune response |

| CR1 | rs6656401 rs3818361 | 1q32 | Complement receptor 1 | LOAD | Mediates cellular binding of immune complexes that activate complement | Immune response |

| DSG2 | rs8093731 | 18q12.1 | Desmoglein 2 | LOAD | Mediates cell–cell junctions between epithelial and other cell type | Cytoskeleton and axonal transport |

| EPHA1 | rs11771145 | 7q34 | EPH Receptor A1 | LOAD | Brain and neural development; angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and apoptosis | Cell adhesion and endocytosis; immune response |

| FERMT2 | rs17125944 | 14q22.1 | Fermitin Family Member 2 | LOAD | Actin assembly and cell shape and mediator of angiogenesis | Tau metabolism |

| HLA-DRB5/DRB1 | rs9271192 | 6p21.3 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR beta 5- DR beta 1 | LOAD | Immunocompetence and histocompatibility | Immune response |

| INPP5D | rs35349669 | 2q37.1 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase | LOAD | Negative regulator of myeloid cell proliferation and survival | Immune response |

| MEF2C | rs190982 | 5q14.3 | Myocyte enhancer factor 2C | LOAD | Controls synapse formation | Immune response |

| MS4A4/MS4A6E | rs983392 rs670139 | 11q12.1 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 4A/6E | LOAD | Signal transduction | Immune response |

| NME8 | rs2718058 | 7p14.1 | NME/NM23 family member 8 | LOAD | Ciliary functions | Cytoskeleton and axonal transport |

| PICALM | rs3851179 rs541458 | 11q14 | Phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein | LOAD | AP2-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Cell adhesion and endocytosis; tau metabolism |

| PSEN1 | – | 14q24.3 | Presenilin 1 | EOAD | Component of catalytic subunit of gamma-secretase complex | Aβ metabolism |

| PSEN2 | – | 1q31-q42 | Presenilin 2 | EOAD | Component of catalytic subunit of gamma-secretase complex | Aβ metabolism |

| PTK2B | rs28834970 | 8p21.1 | Protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta | LOAD | Induction of long term potentiation in hippocampus | Endocytosis |

| SLC24A4/RIN3 | rs10498633 | 14q32.12 | Solute carrier family 24, member 4/ Ras and Rab interactor 3 | LOAD | Brain and neural development | Neural development, synapse function, endocytosis |

| SORL1 | rs11218343 | 11q23.2-q24.2 | Sortilin-related receptor containing LDL receptor class A repeats | LOAD | APOE receptor; binds LDL and RAP and mediates endocytosis of the lipids to which it binds | Cholesterol Metabolism; Cell adhesion and endocytosis |

| TREM2 | rs75932628 | 6p21.1 | Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 | LOAD | Induces phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons, and regulates Toll-like receptor mediated inflammatory responses, and microglial activation | Immune response |

| ZCWPW1 | rs1476679 | 7q22.1 | Zinc finger, CW type with PWWP domain 1 | LOAD | Epigenetic regulation | Epigenetic regulation |

Conclusion

AD is a complex disorder. What we have known is still a drop in the ocean. To improve the prevention and treatment strategies of AD, finding the potential genes in AD pathogenesis and their relationships is a necessary and essential step. It is the fundamental basis for the molecular diagnosis of AD and the mechanistic study on neurodegeneration. Current genetic findings indicated putative disease mechanisms including Aβ metabolism, cell adhesion and endocytosis, immune response, tau metabolism. Future GWASs or next generation sequencing (NGS) approaches studies would keep playing important roles in revealing promising therapeutic targets.

Author Contributions

QS, RL, and YS discussed the concepts and wrote the manuscript. QS, NX, and BT revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program, Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grant No.2016YFC1300500-03 (to YS); National Institute on Aging Grant Nos.NIHR01AG032441-01 (to YS), NIHR21 AG049237 (to RL), and RO1AG025888 (to YS); Alzheimer’s Association Zenith Award and Grant No. IIRG-07-59510 (to YS); American Health Assistance Foundation Grant No. G2006-118 (to RL); and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant No. 81401059 (to QS).

Footnotes

References

- Aiyaz M., Lupton M. K., Proitsi P., Powell J. F., Lovestone S. (2012). Complement activation as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Immunobiology 217 204–215. 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M., Zou F., Chai H. S., Younkin C. S., Crook J., Pankratz V. S., et al. (2012). Novel late-onset Alzheimer disease loci variants associate with brain gene expression. Neurology 79 221–228. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182605801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Vilatela M. E., Lopez-Lopez M., Yescas-Gomez P. (2012). Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Med. Res. 43 622–631. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association (2015). 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 11 332–384. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R., Gill K. D., Mahdi A. A. (2014). Therapeutics of Alzheimer’s disease: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology 76 27–50. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancolio K., Dumanchin C., Barelli H., Warter J. M., Brice A., Campion D., et al. (1999). Unusual phenotypic alteration of beta amyloid precursor protein (betaAPP) maturation by a new Val-715 – > Met betaAPP-770 mutation responsible for probable early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 4119–4124. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen O. M., Reiche J., Schmidt V., Gotthardt M., Spoelgen R., Behlke J., et al. (2005). Neuronal sorting protein-related receptor sorLA/LR11 regulates processing of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 13461–13466. 10.1073/pnas.0503689102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando K., Brion J. P., Stygelbout V., Suain V., Authelet M., Dedecker R., et al. (2013). Clathrin adaptor CALM/PICALM is associated with neurofibrillary tangles and is cleaved in Alzheimer’s brains. Acta Neuropathol. 125 861–878. 10.1007/s00401-013-1111-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arijs I., De Hertogh G., Lemmens B., Van der Goten J., Vermeire S., Schuit F., et al. (2012). Intestinal expression of SHIP in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 61 956–957. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagyinszky E., Youn Y. C., An S. S., Kim S. (2014). The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 9 535–551. 10.2147/CIA.S51571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Sagare A. P., Friedman A. E., Bedi G. S., Holtzman D. M., Deane R., et al. (2007). Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27 909–918. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens K., Brouwers N., Engelborghs S., De Deyn P. P., Van Broeckhoven C., Sleegers K. (2008). SORL1 is genetically associated with increased risk for late-onset Alzheimer disease in the Belgian population. Hum. Mutat. 29 769–770. 10.1002/humu.20725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi A., Anderson C. D., Desikan R. S., Sabuncu M., Cortellini L., Schmansky N., et al. (2010). Genetic variation and neuroimaging measures in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 67 677–685. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornebroek M., De Jonghe C., Haan J., Kumar-Singh S., Younkin S., Roos R., et al. (2003). Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis Dutch type (AbetaPP 693): decreased plasma amyloid-beta 42 concentration. Neurobiol. Dis. 14 619–623. 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutajangout A., Wisniewski T. (2013). The innate immune system in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Cell. Biol. 2013:576383 10.1155/2013/576383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw E. M., Chibnik L. B., Keenan B. T., Ottoboni L., Raj T., Tang A., et al. (2013). CD33 Alzheimer’s disease locus: altered monocyte function and amyloid biology. Nat. Neurosci. 16 848–850. 10.1038/nn.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero M., Rostagno A., Matsubara E., Zlokovic B., Frangione B., Ghiso J. (2000). Apolipoprotein J (clusterin) and Alzheimer’s disease. Microsc. Res. Tech. 50 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano J.M., Kim J., Stewart F.R., Jiang H., DeMattos R.B., Patterson B.W., et al. (2011). Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-beta peptide clearance. Sci. Transl. Med. 3:89ra57 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. H., Kao P. Y., Fan Y. H., Ho D. T., Chan C. S., Yik P. Y., et al. (2012). Polymorphisms of CR1, CLU and PICALM confer susceptibility of Alzheimer’s disease in a southern Chinese population. Neurobiol. Aging 33 210.e1–210.e7. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. I., Tan S. W., Pean C. B., Roostalu U., Vivancos V., Bronda K., et al. (2013). MEF2 is an in vivo immune-metabolic switch. Cell 155 435–447. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M. (2003). TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3 445–453. 10.1038/nri1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crehan H., Holton P., Wray S., Pocock J., Guerreiro R., Hardy J. (2012). Complement receptor 1 (CR1) and Alzheimer’s disease. Immunobiology 217 244–250. 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C., Haller G., Chakraverty S., Mayo K., Vallania F. L., Mitra R. D., et al. (2012). Rare variants in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 increase risk for AD in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease families. PLOS ONE 7:e31039 10.1371/journal.pone.0031039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C., Karch C. M., Jin S. C., Benitez B. A., Cai Y., Guerreiro R., et al. (2014). Rare coding variants in the phospholipase D3 gene confer risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 505 550–554. 10.1038/nature12825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts M., Dermaut B., Rademakers R., Van den Broeck M., Stogbauer F., Van Broeckhoven C. (2003). Novel APP mutation V715A associated with presenile Alzheimer’s disease in a German family. J. Neurol. 250 1374–1375. 10.1007/s00415-003-0182-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fede G., Catania M., Morbin M., Rossi G., Suardi S., Mazzoleni G., et al. (2009). A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science 323 1473–1477. 10.1126/science.1168979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H. K., Gim J. A., Yeo S. H., Kim H. S. (2017). Integrated late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) susceptibility genes: cholesterol metabolism and trafficking perspectives. Gene 597 10–16. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling M. H., Martinez-Climent J. A., Zheng M., Mao J., Rowley J. D., Bohlander S. K. (1996). The t(10;11)(p13;q14) in the U937 cell line results in the fusion of the AF10 gene and CALM, encoding a new member of the AP-3 clathrin assembly protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 4804–4809. 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkelberger J. R., Song W. C. (2010). Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res 20 34–50. 10.1038/cr.2009.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin M. L., Olszowy M. W., Holdorf A. D., Li J., Bromley S., Desai N., et al. (1998). A novel adaptor protein orchestrates receptor patterning and cytoskeletal polarity in T-cell contacts. Cell 94 667–677. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81608-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman C. B., Mehta N. D., Crook R., Perez-tur J., Prihar G., Pfeiffer E., et al. (1997). A new pathogenic mutation in the APP gene (I716V) increases the relative proportion of A beta 42(43). Hum. Mol. Genet. 6 2087–2089. 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. M., Emsley C. L., Gao S., Sahota A., Hall K. S., Farlow M. R., et al. (2000). Serum cholesterol, APOE genotype, and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based study of African Americans. Neurology 54 240–242. 10.1212/WNL.54.1.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone G., Morbin M., Moda F., Botta M., Mazzoleni G., Uggetti A., et al. (2010). Neuropathology of the recessive A673V APP mutation: Alzheimer disease with distinctive features. Acta Neuropathol. 120 803–812. 10.1007/s00401-010-0747-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goate A., Chartier-Harlin M. C., Mullan M., Brown J., Crawford F., Fidani L., et al. (1991). Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 349 704–706. 10.1038/349704a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgaber D., Lerman M. I., McBride O. W., Saffiotti U., Gajdusek D. C. (1987). Characterization and chromosomal localization of a cDNA encoding brain amyloid of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 235 877–880. 10.1126/science.3810169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski T. J., Cho H. S., Vonsattel J. P., Rebeck G. W., Greenberg S. M. (2001). Novel amyloid precursor protein mutation in an Iowa family with dementia and severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann. Neurol. 49 697–705. 10.1002/ana.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R., Wojtas A., Bras J., Carrasquillo M., Rogaeva E., Majounie E., et al. (2013). TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 117–127. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold D., Abraham R., Hollingworth P., Sims R., Gerrish A., Hamshere M. L., et al. (2009). Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 41 1088–1093. 10.1038/ng.440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood D. G., Barker W. W., Loewenstein D. A., Ownby R. L., St George-Hyslop P., Mullan M., et al. (1999). A cross-ethnic analysis of risk factors for AD in white Hispanics and white non-Hispanics. Neurology 52 551–556. 10.1212/WNL.52.3.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen A. L., Smith M. J., Desponts C., Winter O., Moser K., Kerr W. G. (2009). SHIP is required for a functional hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 113 2924–2933. 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks L., van Duijn C. M., Cras P., Cruts M., Van Hul W., van Harskamp F., et al. (1992). Presenile dementia and cerebral haemorrhage linked to a mutation at codon 692 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Nat. Genet. 1 218–221. 10.1038/ng0692-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T., Carson M. J., El Khoury J., Landreth G. E., Brosseron F., Feinstein D. L., et al. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 14 388–405. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S. E., El Khoury J. (2014). TREM2 and the neuroimmunology of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 88 495–498. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth P., Harold D., Sims R., Gerrish A., Lambert J. C., Carrasquillo M. M., et al. (2011). Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 43 429–435. 10.1038/ng.803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mahley R. W. (2014). Apolipoprotein E: structure and function in lipid metabolism, neurobiology, and Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 72 3–12. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mucke L. (2012). Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148 1204–1222. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 Sawcer S., Hellenthal G., Pirinen M., Spencer C. C., et al. (2011). Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476 214–219. 10.1038/nature10251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium Nalls M. A., Plagnol V., Hernandez D. G., Sharma M., Sheerin U. M.et al. (2011). Imputation of sequence variants for identification of genetic risks for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet 377 641–649. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62345-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S. C., Benitez B. A., Karch C. M., Cooper B., Skorupa T., Carrell D., et al. (2014). Coding variants in TREM2 increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23 5838–5846. 10.1093/hmg/ddu277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Harold D., Williams J. (2010). Genetic evidence for the involvement of lipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801 754–761. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T., Stefansson H., Steinberg S., Jonsdottir I., Jonsson P. V., Snaedal J., et al. (2013). Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 107–116. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamino K., Orr H. T., Payami H., Wijsman E. M., Alonso M. E., Pulst S. M., et al. (1992). Linkage and mutational analysis of familial Alzheimer disease kindreds for the APP gene region. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 51 998–1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch C. M., Goate A. M. (2015). Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry 77 43–51. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch C. M., Jeng A. T., Nowotny P., Cady J., Cruchaga C., Goate A. M. (2012). Expression of novel Alzheimer’s disease risk genes in control and Alzheimer’s disease brains. PLOS ONE 7:e50976 10.1371/journal.pone.0050976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Suh J., Romano D., Truong M. H., Mullin K., Hooli B., et al. (2009). Potential late-onset Alzheimer’s disease-associated mutations in the ADAM10 gene attenuate {alpha}-secretase activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 3987–3996. 10.1093/hmg/ddp323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. S., Fitzgerald M. L., Kang K., Okuhira K., Bell S. A., Manning J. J., et al. (2005). Abca7 null mice retain normal macrophage phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol efflux activity despite alterations in adipose mass and serum cholesterol levels. J. Biol. Chem. 280 3989–3995. 10.1074/jbc.M412602200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. S., Guillemin G. J., Glaros E. N., Lim C. K., Garner B. (2006). Quantitation of ATP-binding cassette subfamily-A transporter gene expression in primary human brain cells. Neuroreport 17 891–896. 10.1097/01.wnr.0000221833.41340.cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. S., Weickert C. S., Garner B. (2008). Role of ATP-binding cassette transporters in brain lipid transport and neurological disease. J. Neurochem. 104 1145–1166. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R., Yamamoto M., Morihara T., Akatsu H., Kudo T., Kamino K., et al. (2009). SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease in a Japanese population. Neurosci. Lett. 461 177–180. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingwell K. (2013). Alzheimer disease: BIN1 variant increases risk of Alzheimer disease through tau. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9:184 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimkowicz-Mrowiec A., Sado M., Dziubek A., Dziedzic T., Pera J., Szczudlik A., et al. (2013). Lack of association of CR1, PICALM and CLU gene polymorphisms with Alzheimer disease in a Polish population. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 47 157–160. 10.5114/ninp.2013.33825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunemann H. H., Ridha B. H., Magy L., Wherrett J. R., Hemelsoet D. M., Keen R. W., et al. (2005). The genetic causes of basal ganglia calcification, dementia, and bone cysts: DAP12 and TREM2. Neurology 64 1502–1507. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000160304.00003.CA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K., Klein R. (2002). Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 475–486. 10.1038/nrm856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar-Singh S., De Jonghe C., Cruts M., Kleinert R., Wang R., Mercken M., et al. (2000). Nonfibrillar diffuse amyloid deposition due to a gamma(42)-secretase site mutation points to an essential role for N-truncated A beta(42) in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 2589–2598. 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K. O., Ip N. Y. (2009). Synapse development and plasticity: roles of ephrin/Eph receptor signaling. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19 275–283. 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. C., Heath S., Even G., Campion D., Sleegers K., Hiltunen M., et al. (2009). Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 41 1094–1099. 10.1038/ng.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. C., Ibrahim-Verbaas C. A., Harold D., Naj A. C., Sims R., Bellenguez C., et al. (2013). Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 45 1452–1458. 10.1038/ng.2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammich S., Kojro E., Postina R., Gilbert S., Pfeiffer R., Jasionowski M., et al. (1999). Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 3922–3927. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Leugers C. J. (2012). Tau and tauopathies. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 107 263–293. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385883-2.00004-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Cheng R., Honig L. S., Vonsattel J. P., Clark L., Mayeux R. (2008). Association between genetic variants in SORL1 and autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer disease. Neurology 70 887–889. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280581.39755.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E., Wasco W., Poorkaj P., Romano D. M., Oshima J., Pettingell W. H., et al. (1995). Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s disease locus. Science 269 973–977. 10.1126/science.7638622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy E., Carman M. D., Fernandez-Madrid I. J., Power M. D., Lieberburg I., van Duinen S. G., et al. (1990). Mutation of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid gene in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage, Dutch type. Science 248 1124–1126. 10.1126/science.2111584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Karl T., Garner B. (2015). Understanding the function of ABCA7 in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43 920–923. 10.1042/BST20150105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. L., Shi S. S., Guo Q. H., Ni W., Dong Y., Liu Y., et al. (2011). PICALM and CR1 variants are not associated with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese patients. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 25 111–117. 10.3233/JAD-2011-101917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. C., Liu C. C., Kanekiyo T., Xu H., Bu G. (2013). Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9 106–118. 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Perez E., Zhang Y., Frank S. J., Creemers J., Seidah N., Checler F. (2001). Constitutive alpha-secretase cleavage of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in the furin-deficient LoVo cell line: involvement of the pro-hormone convertase 7 and the disintegrin metalloprotease ADAM10. J. Neurochem. 76 1532–1539. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue L. F., Schmitz C., Walker D. G. (2015). What happens to microglial TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease: immunoregulatory turned into immunopathogenic? Neuroscience 302 138–150. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Yang H., Qi J., Liu D., Xiong P., Xu Y., et al. (2010). CD2AP is indispensable to multistep cytotoxic process by NK cells. Mol. Immunol. 47 1074–1082. 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley R. W., Rall S. C., Jr. (2000). Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1 507–537. 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik M., Simpson J. F., Parikh I., Wilfred B. R., Fardo D. W., Nelson P. T., et al. (2013). CD33 Alzheimer’s risk-altering polymorphism, CD33 expression, and exon 2 splicing. J. Neurosci. 33 13320–13325. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1224-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M.G., Pfrieger F., Dotti C.G. (2014). Cholesterol in brain disease: sometimes determinant and frequently implicated. EMBO Rep. 15 1036–1052. 10.15252/embr.201439225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P. C., Lampert-Etchells M., Johnson S. A., Poirier J., Masters J. N., Finch C. E. (1990). Dynamics of gene expression for a hippocampal glycoprotein elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and in response to experimental lesions in rat. Neuron 5 831–839. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90342-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier B., Quaranta M., Daviet L., Hatzoglou A., Leprince C. (2009). The membrane-tubulating potential of amphiphysin 2/BIN1 is dependent on the microtubule-binding cytoplasmic linker protein 170 (CLIP-170). Eur. J. Cell Biol. 88 91–102. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson D. M. (2014). APOE epsilon4: the most prevalent yet understudied risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10 861–868. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan M., Crawford F., Axelman K., Houlden H., Lilius L., Winblad B., et al. (1992). A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer’s disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of beta-amyloid. Nat. Genet. 1 345–347. 10.1038/ng0892-345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naj A. C., Jun G., Beecham G. W., Wang L. S., Vardarajan B. N., Buros J., et al. (2011). Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 43 436–441. 10.1038/ng.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutinen T., Suuronen T., Kauppinen A., Salminen A. (2009). Clusterin: a forgotten player in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Rev. 61 89–104. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R. J., Wong P. C. (2011). Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 185–204. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T., Pasinetti G. M., Osterburg H. H., Anderson C., Johnson S. A., Finch C. E. (1994). Purification and characterization of brain clusterin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 204 1131–1136. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offe K., Dodson S. E., Shoemaker J. T., Fritz J. J., Gearing M., Levey A. I., et al. (2006). The lipoprotein receptor LR11 regulates amyloid beta production and amyloid precursor protein traffic in endosomal compartments. J. Neurosci. 26 1596–1603. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4946-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F., Frisardi V., Seripa D., D’Onofrio G., Santamato A., Masullo C., et al. (2012). Apolipoprotein E genotypes and neuropsychiatric symptoms and syndromes in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 11 87–103. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalar P., Najmabadi H., Noorian A. R., Moghimi B., Jannati A., Soltanzadeh A., et al. (2002). An Iranian family with Alzheimer’s disease caused by a novel APP mutation (Thr714Ala). Neurology 58 1574–1575. 10.1212/WNL.58.10.1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinetti G. M. (1996). Inflammatory mechanisms in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of the complement system. Neurobiol. Aging 17 707–716. 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00113-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proitsi P., Lee S. H., Lunnon K., Keohane A., Powell J., Troakes C., et al. (2014). Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility variants in the MS4A6A gene are associated with altered levels of MS4A6A expression in blood. Neurobiol. Aging 35 279–290. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokic I., Cowling B. S., Laporte J. (2014). Amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) in physiology and diseases. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 92 453–463. 10.1007/s00109-014-1138-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga P., Calvo C., Albala C., Urquidi J., Santos J. L., Perez H., et al. (1999). Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in elderly Chilean people with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 18 48–52. 10.1159/000026195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Bermudez J. (2012). Alzheimer’s disease: critical notes on the history of a medical concept. Arch. Med. Res. 43 595–599. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C. (2013). Dyslipidemia and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 15 307 10.1007/s11883-012-0307-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C., Brayne C., Mayeux R. (2011). Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 7 137–152. 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R., Timchenko N. A., Miller J. W., Reddy S., Caskey C. T., Swanson M. S., et al. (1997). Altered phosphorylation and intracellular distribution of a (CUG)n triplet repeat RNA-binding protein in patients with myotonic dystrophy and in myotonin protein kinase knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 13221–13226. 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev E. I., Sherrington R., Rogaeva E. A., Levesque G., Ikeda M., Liang Y., et al. (1995). Familial Alzheimer’s disease in kindreds with missense mutations in a gene on chromosome 1 related to the Alzheimer’s disease type 3 gene. Nature 376 775–778. 10.1038/376775a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohn T. T. (2013). The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2: “TREM-ming” the inflammatory component associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:860959 10.1155/2013/860959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P., Lichtenthaler S. F. (2015). The alpha secretase ADAM10: a metalloprotease with multiple functions in the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 135 1–20. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamuro D., Elliott K. J., Wechsler-Reya R., Prendergast G. C. (1996). BIN1 is a novel MYC-interacting protein with features of a tumour suppressor. Nat. Genet. 14 69–77. 10.1038/ng0996-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharenberg A. M., El-Hillal O., Fruman D. A., Beitz L. O., Li Z., Lin S., et al. (1998). Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3)/Tec kinase-dependent calcium signaling pathway: a target for SHIP-mediated inhibitory signals. EMBO J. 17 1961–1972. 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzer C. R., Offe K., Gearing M., Rees H. D., Fang G., Heilman C. J., et al. (2004). Loss of apolipoprotein E receptor LR11 in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 61 1200–1205. 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnetz-Boutaud N. C., Hoffman J., Coe J. E., Murdock D. G., Pericak-Vance M. A., Haines J. L. (2012). Identification and confirmation of an exonic splicing enhancer variation in exon 5 of the Alzheimer disease associated PICALM gene. Ann. Hum. Genet. 76 448–453. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2012.00727.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S., Fitzpatrick A. L., Ikram M. A., DeStefano A. L., Gudnason V., Boada M., et al. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 303 1832–1840. 10.1001/jama.2010.574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharfe N., Nikolic M., Cimpeon L., Van De Kratts A., Freywald A., Roifman C. M. (2008). EphA and ephrin-A proteins regulate integrin-mediated T lymphocyte interactions. Mol. Immunol. 45 1208–1220. 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R., Rogaev E. I., Liang Y., Rogaeva E. A., Levesque G., Ikeda M., et al. (1995). Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 375 754–760. 10.1038/375754a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih N. Y., Li J., Cotran R., Mundel P., Miner J. H., Shaw A. S. (2001). CD2AP localizes to the slit diaphragm and binds to nephrin via a novel C-terminal domain. Am. J. Pathol. 159 2303–2308. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63080-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman J. M., Imboywa S., Giagtzoglou N., Powers M. P., Hu Y., Devenport D., et al. (2014). Functional screening in Drosophila identifies Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility genes and implicates Tau-mediated mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23 870–877. 10.1093/hmg/ddt478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. H., Ashton G. H., Penagos H. G., Lee J. V., Feiler H. S., Wilhelmsen K. C., et al. (2003). Loss of kindlin-1, a human homolog of the Caenorhabditis elegans actin-extracellular-matrix linker protein UNC-112, causes Kindler syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73 174–187. 10.1086/376609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siest G., Pillot T., Regis-Bailly A., Leininger-Muller B., Steinmetz J., Galteau M. M., et al. (1995). Apolipoprotein E: an important gene and protein to follow in laboratory medicine. Clin. Chem. 41(8 Pt 1) 1068–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly L. M., Ho V., Antignano F., Ruschmann J., Hamilton M., Lam V., et al. (2007). The role of SHIP in macrophages. Front. Biosci. 12 2836–2848. 10.2741/2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly L. M., Rauh M. J., Kalesnikoff J., Buchse T., Krystal G. (2003). SHIP, SHIP2, and PTEN activities are regulated in vivo by modulation of their protein levels: SHIP is up-regulated in macrophages and mast cells by lipopolysaccharide. Exp. Hematol. 31 1170–1181. 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofola O. A., Jin P., Qin Y., Duan R., Liu H., de Haro M., et al. (2007). RNA-binding proteins hnRNP A2/B1 and CUGBP1 suppress fragile X CGG premutation repeat-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of FXTAS. Neuron 55 565–571. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H., Fluhrer R., Haass C. (2008). Intramembrane proteolysis by gamma-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 283 29627–29631. 10.1074/jbc.R800010200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet R. A., Bennett D. A., Graff-Radford N. R., Mayeux R. National Institute on Aging Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study Group (2010). Assessment and familial aggregation of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease from the National Institute on Aging Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study. Brain 133 1155–1162. 10.1093/brain/awq001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. K., Lee J., Chen C. P., Teo Y. Y., Zhao Y., Lee W. L. (2009). SORL1 haplotypes modulate risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese. Neurobiol. Aging 30 1048–1051. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L., Yu J. T., Zhang W., Wu Z. C., Zhang Q., Liu Q. Y., et al. (2013). Association of GWAS-linked loci with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a northern Han Chinese population. Alzheimers Dement 9 546–553. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M.S., Yu J.T., Tan L. (2013). Bridging integrator 1 (BIN1): form, function, and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol. Med. 19 594–603. 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N., Abe-Dohmae S., Iwamoto N., Yokoyama S. (2011). Roles of ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 in cholesterol homeostasis and host defense system. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 18 274–281. 10.5551/jat.6726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebar F., Bohlander S. K., Sorkin A. (1999). Clathrin assembly lymphoid myeloid leukemia (CALM) protein: localization in endocytic-coated pits, interactions with clathrin, and the impact of overexpression on clathrin-mediated traffic. Mol. Biol. Cell 10 2687–2702. 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y., Chang J. C., Fan E. Y., Flajolet M., Greengard P. (2013). Adaptor complex AP2/PICALM, through interaction with LC3, targets Alzheimer’s APP-CTF for terminal degradation via autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 17071–17076. 10.1073/pnas.1315110110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch S., Hamamichi S., Goodman J. L., Matlack K. E., Chung C. Y., Baru V., et al. (2011). Functional links between Abeta toxicity, endocytic trafficking, and Alzheimer’s disease risk factors in yeast. Science 334 1241–1245. 10.1126/science.1213210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowsdale J., Knight J. C. (2013). Major histocompatibility complex genomics and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 14 301–323. 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y., Wu S., Shi X., Chen K., Wu C. (2003). Migfilin and Mig-2 link focal adhesions to filamin and the actin cytoskeleton and function in cell shape modulation. Cell 113 37–47. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardarajan B. N., Bruesegem S. Y., Harbour M. E., Inzelberg R., Friedland R., St George-Hyslop P., et al. (2012). Identification of Alzheimer disease-associated variants in genes that regulate retromer function. Neurobiol. Aging 33 2231.e15–2231.e30. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]