ABSTRACT

Background:

This study examined the impacts of an Emotional Focused Intervention on emotional abuse behaviors and marital satisfaction among the elderly married couples.

Methods:

This randomized controlled trial study was carried out in Shiraz-Iran, during September 2013-2014. The elderly couples were invited to join an emotional focused intervention, following the advertisement and announcement on bulletin boards in the elderly day clinic centers and all governmental primary health care centers. Then, 57 couples (114 participants) who were eligible for study were assigned in two groups by block randomization (29 in the experimental and 28 in the control group(.The couples in the experimental group received intervention twice a week for four weeks. Each session lasted 90 minutes. The control group didn’t receive any intervention and the subjects were put in the waiting list. The outcome measures were evaluated by Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse Questionnaire (MMEAQ) and Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire for Older People (MSQFOP). Repeated measurement ANOVA was used to detect any significant changes between groups in their mean scores of emotional abuse behaviors and marital satisfaction from pre- to post-test, and 3 months after the intervention. Analysis of data was performed using SPSS, version 19, and P≤0.05 was measured as significant.

Results:

The mean duration of marriage was 39.56±9.64 years. In the experimental group, the abusive behaviors decreased significantly (P<0.001) at times 2 and 3 compared with time 1, and marital satisfaction improved significantly only at time 3 (P<0.001). These differences were not significant in the control group.

Conclusion:

Emotion-focused couple-based interventions are helpful in reducing the spousal emotional abuse and improving marital satisfaction in among the elderly couples.

Trial Registration Number: 2013111715426N1

KEYWORDS: Spouse abuse, Emotion, Aged, Satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

Emotional abuse comprises a large part of many couples’ lives. The results of an investigation in the United States revealed that 48.8% of men and 48.4% of women reported that they had been victims of emotional abuse or psychological aggression during their lives.1 Emotional abuse was the most common type of intimate partner violence among Korean-American women in all age groups.2 Studies of emotional spousal abuse among the elderly couples in Iran are rare, but the findings of an investigation on spousal abuse among 1000 married women aged 18-45 years in Tehran revealed that 89.7% of these women experienced emotional spousal abuse without complaints.3 Findings of an investigation in six health care centers in Tehran city found that 41.75% of the 384 married women studied had experienced spousal abuse, the most frequent types of which were huffing, ignoring humiliating, blaming, and insulting.4 Despite the considerable growth in Iran’s elderly population,5 spousal abuses in this social group have not received enough attention. Therefore, the globally rapid rise in the aging population and greater vulnerability of older people 6 necessitate researches to be conducted on spousal abuse among the elderly couples.

Physiological changes and longer life expectancies place the elderly couples at particular risk for abuse.7 Even in thriving relationships in long-term marriages lasting for several decades, aging people are more at risk and more vulnerable to abuse because of disability and disease.8 In the last decade, many investigations were carried out on “partner violence” among the elderly women,9-14 but available studies regarding effective intervention and treatment are limited, while the improvement of effective interventions for the elderly victims of abuse is a strong priority.15 long-term marriages, the elderly, both the abused and abuser, are ashamed of their abusive behavior and try to hide it from investigators. A potent mix of guilt, fear, and dependence upon a spouse often prevents a domestic violence victim from seeking help, even though they really need it.

Long-term domestic aggression negatively effects the quality of life and health of its victims and leads to increased utilization of health services,16 which raises the costs for the society.17 The annual healthcare costs of women abused by their intimate partners are about 92% more than men in general.18 Some studies revealed that the elderly abused women reported considerably more health problems such as digestive problems, bone and joint pain, and hypertension than those who were not abused.19,20 A negative relationship was reported between the prevalence of spousal abuse and psychological well-being among the women of Jordan.21 The results of an investigation revealed that the victims of intimate partner abuse complained of different physical and mental health problems such as chronic pain, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression.22 Health care professionals have a main role in detecting and recognizing the elderly abuse; undoubtedly increasing recognition and proper early intervention by health care professionals for spousal abuse will improve the health, quality of life,23 and marital satisfaction of many elderly couples who suffer from abuse.

Marital relationship is in every society and is well-known as one of the most important resources in human relationships.24 Married women and men are often healthier, happier, and report higher well-being and are less stressed than their unmarried counterparts.25 The quality of marital relationship can be measured by pleasure, happiness, affection, tenderness, love, intimacy, hearty communication, and marital satisfaction and is related with the level of these individualities.26 The results of an investigation in Iran revealed that emotional wellbeing of the couple was strongly affected by the high quality of marital relationship.27 Previous studies revealed that marital satisfaction is linked to the partner’s emotional understanding, emotional support, conflict resolution, and solving problem.26 But it is still unclear whether Emotional Abuse Behaviors (EAB) and marital satisfaction among the married elderly couples might be affected by an emotional focused intervention. Therefore, due to the lack of emotional focused intervention for the treatment of the elderly couples, this study aimed to examine the effects of an emotion-focused psycho-educational intervention on emotionally abusive behaviors and marital satisfaction among the married elderly couples who suffer from frequent emotionally abusive behaviors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized, controlled trial with pre-tests, post-tests, and follow-up was conducted during September 2013-2014 in Shiraz- Iran, on 57 elderly couples (114 participants). The sample size was determined by G power, with an assumption effect size of 0.40 and power of 0.80; finally, a minimum of 52 applicants were determined. To account for dropout, 58 applicants were needed, but the focus of this study was on couples due to the type and nature of treatment that has been chosen for couple therapy; therefore, 58 couples=116 participants were recruited and assigned by block randomization in the two groups (Experimental=29 couples), (and Control=29 couples).

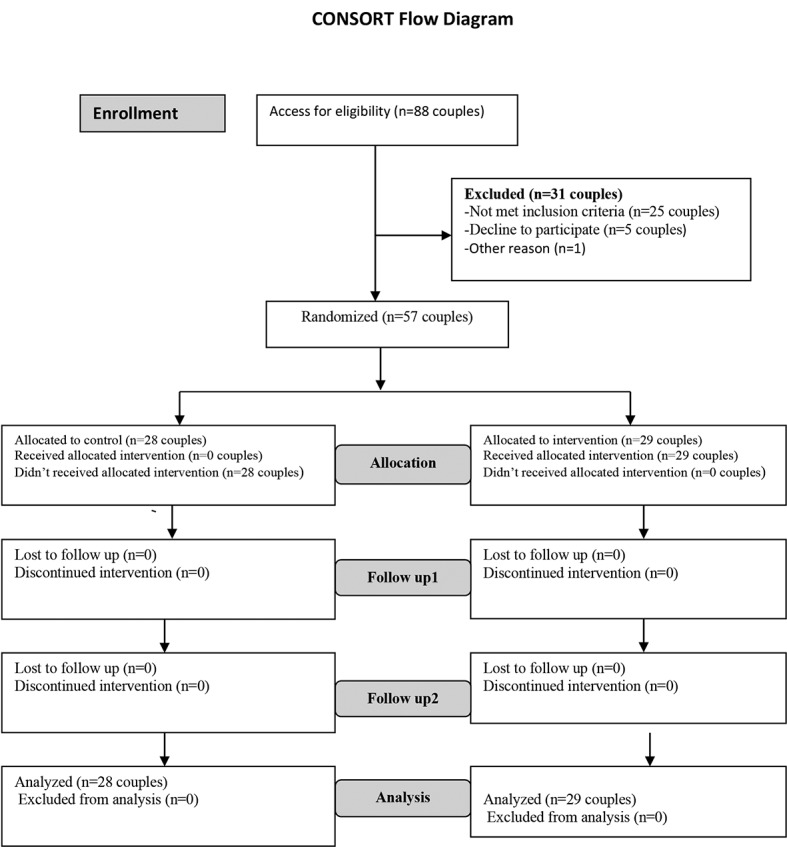

For sampling, at first, the elderly couples were invited to join a program for an emotionally intimate relationship which was advertised and announced on bulletin boards in the elderly day clinic centers and all primary health care centers affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for 3 months. This announcement informed the couples of some of the inclusion and exclusion criteria which were as follows: couples must be aged 60 years or older and have had emotional difficulties in their intimate relationship for more than 6 months, both partners must register, the marriage must have lasted at least 5 years, the couple must live together, both partners must be able to participate in an interventional group, and they must sign a consent form. Couples were excluded if they had a history of a major psychiatric disorder (such as schizophrenia, dementia, or depression) or a history of current drug or alcohol abuse, use of antidepressant, anti-anxiety, or narcotic drugs, if they were currently enrolled in any other psychological treatment program, if one member of the couple had difficulty with Activity Daily Livings (ADLs) and was dependent upon his/her spouse for performing daily activities, or if the couples experienced abuse (physical, financial, sexual) other than emotional as identified by the Abusive Behavior Inventory introduced by Sheperd and Campbell in 1992.27 Data at time 1 were collected before the intervention by means of a demographic characteristics form, the Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse Questionnaire (MMEAQ), and the Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire for Older People (MSQFOP). Participants who were unable to complete these tools on their own were assisted by a trained nurse who was blind to the intervention and who asked the participants some questions and recorded their answers. Then, block randomization was performed to achieve a random equal allocation into the two study groups. Fifty-seven couples were randomly assigned in the experimental (29 couples), and control groups (28 couples).The couples in the experimental group were then randomly divided into 7 small groups (6 groups with 4 couples and one group with 5 couples). An emotion-focused psycho-educational intervention was carried out for all couples in the experimental group; one session of preparation and a total of eight 90-minute sessions were held twice a week for 4 weeks. The control group received no intervention and was put on a waiting list. Finally, data were collected from both groups using the MMEAQ and the MSQFOP immediately after the intervention in week 5 (Time 2) and three months after the intervention in week 16 (Time 3). Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 19, and P≤0.05 was considered as significant. Figure 1 illustrates the consort flow chart28 of the study.The Emotional Focused Psycho-educational Intervention (EFPEI) for the elderly couples was designed based on nine steps of Emotional Focused Therapy for Couples (EFT-C) which was explained by Greenberg and Johnson.29 he title, objectives, and exercises of each session were also determined based on the EFT-C. Table 1 illustrates the titles, objectives, and activities of the nine sessions of EFPEI.

Figure1.

Consort flow chart for the recruitment process

Table 1.

The titles, objectives, and activities of nine sessions of Emotional Focused Psycho-educational Intervention

| Sessions | Objectives | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | To describe the goal of intervention, and discuss about the emotional abusive behaviors. To explain the ground rules, rights and responsibilities of group members, issues of confidentiality | Welcoming, greeting, and introducing basic rules for group. |

| Title: Basic information, the goals and the rule of group | Describing the significant role of emotion experience in their marital relationship. | |

| Session 1, | To create a therapeutic alliance with clients to feel be supported, safe, accepted and understood by their counselor. | Makes a shared experience with the clients and acts as echoes and mirrors for the client by verbal and non-verbal response |

| Title: Creating a therapeutic alliance and assessment: (step 1) | To take a relationship history from the couples, by explaining about their intimate relationship, and marital status, | Asking the couples to explain a brief of their marriage history and relationship. |

| To discuss the relational conflict issue of each partner. To talk about their main attachment needs. | To give a scenario of a conflict relationship situation and ask the partner to put themselves in this situation and talk about their reaction to this situation | |

| Session 2 | To identify the negative interactive cycle in couples. | The participants have been asked to discus and answer to this question” when you and your partner are not getting along what’s your feeling, thoughts, and doing” |

| Title: Assessing partner’s interaction, and identify the negative interactive cycle: (step 2) | To identify the couple’s doing, feeling, and thoughts when they are not getting along together. | The participants have been asked to discus and answer to the second question ‘how do you interact during conflicts’ |

| To identify the common negative interactive cycle in groups | ||

| To Assess the Partners’ Interactions | ||

| To identify the type of attachment style in each partner. | ||

| Session 3 | To access the primary unappreciated emotions in interactional positions | A scenario about the relationship conflict was presented to couples and explained about the primary and secondary emotions of the cases and then the participants were be asked to talk about their experience in the daily relationship with their partner about their primary, and secondary emotions .A list of positions, primary emotion, and secondary emotion of each couples in group were be detected by counselor |

| Title: Access unappreciated feelings causal interactional positions, and redefines the problem(s): (step3&4) | To reframe the primary emotions and attachment needs | |

| To help the couples develop their perceptive of the problem as a cycle or recurring pattern that is affected by both partner’s attachment needs and emotional response in their bond | ||

| Session 4 | To reengage the withdrawn partners in relationship. | Helping the withdrawn partners to raise their understanding of engagement with, and ownership of the attachment impotent, hurts, and fears |

| Title: Enhancing recognition the reject needs and aspects of self, and facilitate in acceptance: (Step 5) | To have more blaming partners “soften”, and ask for their attachment needs | Assist to blaming partners to hear and accept these hurts and fears. |

| Helping the partners shift into deeper relationship with their own emotional experience. | ||

| Session 5 | To have a new form of emotional engagement. | Helping the observing partner or the witness to hear, understand, accept, and respond the fears and hurts of the other. |

| Title: Promote receiving partner’s experience by each partner: (step 6) | To make new information and, more significantly create a “new way of being” to the other. | Acceptance engages a shift in insight-“seeing” the other in a new light. For example a partner who is perceived by her husband as “distant and cold’ starts to disclose deep shame and fear of emotion exposed. |

| To form a new level of engagement or reengagement of key emotions with the partner | ||

| Session 6 | To help the partners to clarify their wishes and desires | Ask the partner to talk about their unappreciated wishes and desires |

| Title: Facilitate the expression of needs to reorganize the interaction: (step 7) | Softening the blamer to become more mutually accessible and responsive. | To help the partners to share their attachment needs. |

| To able the partners to share their attachment needs. | Ask the couples to talk their experience about their attachment needs that be met | |

| Session 7 | Helping the partners to maintain the new patterns of linking that they have developed | To ask the withdrawn partner to explain their problems that has been avoided. |

| Title: Establish the emergence of innovative solutions: (step 8) | To be able to talk about their problem in their relationship and show greater security among them. | Couples be able to explain behaviors that they are engaging in new patterns in their linking, |

| Integrating of secure patterns among the couples in their everyday interactions, and promoting healthy patterns of interaction by partner accessibility and responsiveness | To observe and talking about the changes occur in their relationship through the counseling sessions | |

| Session 8 | Helping the couples to review what changes have been occurred in their relationship in a form of narrative. | In termination step security of the couple’s relationship are assessed in a narrative story. |

| Title: Consolidate the new positions: (step 9) | Promoting and support their emotional experiences related with their behaviors in the past and present. | The couples review and talk about what changes have been occurred in their relationship |

| Focusing on methods that they have found to leave the cycle. | The couples talk about the ways that they have found to leave the cycle. | |

| Highlighting the potential that help to protect and supporting these changes | The couples demonstrate a lot of bravery in their living for each other especially when the life gets difficult. | |

| The couples talk how to protect and supporting these changes |

The antecedent variables were assessed by a demographic questionnaire which included age, education level, monthly income, duration of marriage, number of children, and experience of child abuse or witnessing abuse by parents. Abusive Behavior Inventory was applied to detect the couples who suffered from only emotional abuse, and excluded those couples experiencing other types or mixed types of abuse. This 30-item tool was made to measure different types of abuse; the psychological subscale includes 17 items. The acceptable validity and reliability (alpha coefficients=0.7 to 0.92) was reported by Shepard, and Campbell (1992) in four groups of abuser, abused, non-abuser, and non-abused people.27 These two questionnaires were applied only one time before the intervention.

The frequency and different types of emotionally abusive behaviors were measured using the MMEAQ. This 28-item questionnaire was made by Murphy and Hoover in 1999. Items were scored 0 (this has never happened), 1 (once), 2 (twice), 3 (3-5 times), 4 (6-10 times), 5 (11-20 times), and 6 (more than 20 times). Higher scores showed a higher level of emotional abuse. Moreover, each item of the questionnaire had two parts: the abusive behavior was exhibited by the applicant, and the abusive behavior was exhibited by the applicant’s partner. In the current article, only the first part of the data (self-evaluation of abuse) is reported; the second part (partner evaluation) will be discussed in a future article. Marital satisfaction was measured using the MSQFOP developed by Haynes et al., 1992.30

The 24 items could regularly be answered in 6-8 min. It is noteworthy that the MSQFOP was designed as a marital satisfaction questionnaire principally proper for older people. However, whether or not the MSQFOP is a more sensitive, reliable, and valid instrument than others currently available ones was not examined.

This study employed the MMEAQ and MSQFOP instruments for the first time ever in Iran. Therefore, the Persian versions of these instruments were checked for validity and reliability among the Iranian elderly. A pilot study was conducted on a sample of 30 elderly people to identify the internal consistency, appropriateness, feasibility, and stability of the instruments.

Different domains in the questionnaires were evaluated for internal consistency by using Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Persian versions of MMEAQ and MSQFOP were 0.80 and 0.96, respectively; therefore, the instruments were easily comprehended by the Iranian elderly people who participated in the pilot study. Moreover, an expert panel review was performed to evaluate the content validity. A panel of five expert analysts examined all the items of the questionnaires to detect whether each item was completely relevant (100%) (4), fairly relevant (75%) (3), less relevant (50%) (2), or insufficiently relevant (25%) (1). The results illustrated an acceptable validity (CVI=92.19) for these instruments.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Research Committee of Medical and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia (UPM). In addition, the proposal was also approved by Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in Iran (Ethical code 2012-114).

Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis, Chi-square test, t-test, and mixed between-within subject Repeated Measurement ANOVA. The significance level for alpha was considered at 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 88 couples (176 participants) who were enrolled in the study, three were excluded because their husbands were addicted to opium, and two couples were excluded because the wives were taking anti-depressant drugs. Then, the 83 couples who met the inclusion criteria were screened for Emotionally Abusive Behaviors (EAB). The results revealed that in 58 couples (68.9%), both husbands and wives reported experiencing EAB (at least one EAB four times or more in their relationships with their spouses 6 months prior to the study). Twenty-five (31.1%) couples reported mixed types of abuse; they were excluded from the study and referred to a psychologist or family therapist. One couple was excluded from the study due to personal problems. Ultimately, 57 couples (114 participants) were recruited, signed the consent form, and participated in the study. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 2.

Demographic variables of the participants (participants=114)

| Variables | Mean±SD | Range(years) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.58±6.81 | 60-87 | |

| 60-70 y | 92 (80.70) | ||

| 71-80 y | 14 (12.28) | ||

| 81-90 y | 8 (7.02) | ||

| Education | |||

| Primary/secondary | 76 (66.67) | ||

| Diploma | 23 (20.18) | ||

| Tertiary Education | 15 (13.16) | ||

| Personal monthly Income | |||

| <1 million tomansa | 84 (73.68) | ||

| 1-2 million tomans | 19 (16.67) | ||

| >2 million tomans | 6 (5.26) | ||

| Missing | 5 (4.39) | ||

| Duration of marriage | 39.56±9.64 | 8-57 | Couples (n=57) |

| <10year | 1 (1.75) | ||

| 10- 20 y | 2 (3.50) | ||

| 21-30 y | 4 (7.01) | ||

| 31-40 y | 26 (45.50) | ||

| >40 | 24 (42.10) | ||

| Experience of childhood abuse by parents | |||

| Yes | 23 (20.18) | ||

| No | 91 (79.82) | ||

| Experience of childhood Witness of abuse | |||

| Yes | 22 (19.30) | ||

| No | 92 (80.70) | ||

1 million tomans~307 USD

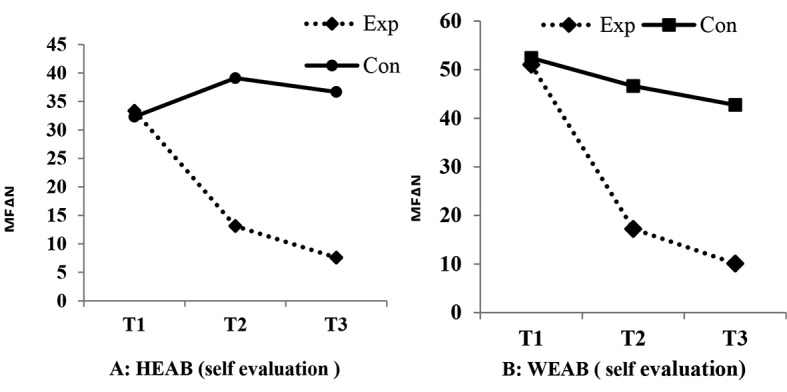

The mean age of the participants was 65.58±6.81 years; the majorities (80.70%) were aged between 60 and 70 years. The mean duration of marriage was 39.56±9.64 years. The majority of wives and husbands reported no childhood experience of abuse (79.82) or witness of abuse (80.70) by their parents. Baseline assessments of all variables (socio-demographic characteristics, duration of marriage, and experience of child abuse, witness of abuse by parents, emotional abuse, and marital satisfaction) were made in the experimental and control groups, and the results were compared. No significant differences were found in the study variables, between the two groups, before intervention (Table 2). Repeated measure ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of EFPEI on self-evaluation of EAB and Marital Satisfaction (MS(. The results revealed that changes in the mean scores of the husbands’ Emotional Abuse Behavior (HEAB) were significantly different between the two groups (P<0.001) over the studied times (P<0.001). The interaction between group and time was also significant [F (1.465, 80.59)=25.795, P<0.001, η2=0.319] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean value changes of husbands’ emotional abuse behaviors (self-evaluation) by time and group

| HEABa | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time | P value* | Time* Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Group | |||

| Experimental | 33.37±16.89 | 13.13±9.36 | 7.58±4.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Control | 32.32±26.37 | 39.10±26.32 | 38.82±25.74 |

Husbands’ Emotional Abuse Behavior;

Repeated measure

In the experimental group, the mean scores of the Wives’ Emotional Abuse Behavior (WEAB) also significantly decreased from 51.03±16.61 (Time1) to 17.24±10.83 (Time2) and 10.10±7.13 (Time3).The results revealed that the mean of WEAB was significantly different between two groups (P<0.001).The mean changes were not significant during the three times between the two groups (P=0.252) (Table 4). In the control group, a slightly significant decrease (mean difference=9.679, standard error=3.754, P<0.027, η2=0.140) was also found in T3 compared with T1.

Table 4.

Mean value changes of the wives’ emotional abuse behaviors (self-evaluation) by time and group

| WEABa | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time | P value* | Time* Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Group | |||

| Experimental | 51.03±16.61 | 17.24±10.83 | 10.10±7.13 | 0.252 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Control | 52.42±24.30 | 46.64±17.23 | 42.75±12.14 |

Wives’Emotional Abuse Behaviors;

Repeated measure

The means of the husbands’ and wives’ emotional abuse in the experimental and control groups are shown in figure 2. Clearly, the mean HEAB score in the experimental group at T3 decreased about 25 units from that of T1, while it remained consistent in the control group (figure 2). The mean of WEAB in the experimental group decreased significantly by nearly 41 units at T3 compared with T1. Also in the control group, a slightly significant decrease of about 10 units was found in T3 compared with T1 (figure 2).

Figure2.

Meanplot of A: husbands’ emotional abuse behaviors (HEAB) and B: wives’ emotional abuse behaviors (WEAB) in the experimental and control groups

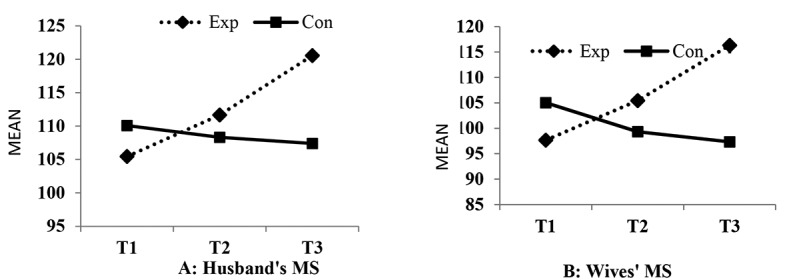

Repeated measure ANOVA was also conducted to examine the effects of the intervention on the Husbands’ Marital Satisfaction (HMS), and Wives’ Marital Satisfaction (WMS). Pairwise comparisons showed that the mean difference of HMS was not significant from pre- to post-test, but from pre-test to follow-up, it was significant (P<0.001). None of the test results was significant in the control group. The findings showed that the mean WMS score was significantly increased by the intervention in the experimental group in the three times, while it slightly decreased in the control group. figure 3 shows the plot of husbands’ and wives’ mean MS scores in both experimental and control groups. As shown in Figure 3A, the mean of HMS was significantly increased (about 15 units) at follow-up (T3) compared with pretest (T1) in the experimental group, while these results were not significant for the control group in all tests (P>0.05). The plot of the wives’ mean MS scores is shown in Figure 3-B, illustrating that the wives’ mean MS scores were significantly increased (18 units) at T3 compared with T1, but in the control group, the wives’ mean MS score decreased by 7 units at T3 compared with T1.

Figure3.

Mean plot of A: husbands’ marital satisfaction and B: wives’ marital satisfaction means scores in both experimental and control groups

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effects of EFPEI on EAB and MS among Iranian elderly couples with frequent emotionally abusive behaviors in the experimental and control groups at 3 different times. The results of testing before the intervention revealed that 58 (68.9%) out of the 83 couples registered to participate in the study reported that both husbands and wives experienced EAB. This illustrates the reciprocity of the spousal emotional abuse in long-term marriages. Similarly, a strong relationship was reported between female and male victimization, signifying the reciprocity of aggressive behavior in the couples.31 The former research indicated that partner violence and aggression are not a merely male phenomenon and are often reciprocal in couples.32,33 The most common type of violence in intimate relationships is bidirectional spousal violence;32 therefore, it is essential to consider the dyadic mechanisms of taking violent relationships into account with both husbands and wives when evaluating the emotional relationships between couples.

In the current study, no significant correlation was found between age, income, and education level, duration of marriage and EAB and MS. These results may be related to life expectancy, which is completely different between young and elderly couples. In an investigation on 300 married Iranian females between 25-34 years of age, a significant relationship was found between the husband’s income and his emotional violence.34 No significant association was found between those who experienced childhood abuse or those who witnessed abuse by parents and EAB. This result may lie in the fact that the older couples participating in the study were asked whether they had experienced child abuse or witnessed as a child abuse by parents. The majority of them answered “No” to questions. It is believed that the real rate may be higher. Some studies indicated that adult survivors of child abuse do not actually view themselves as abused individuals; they minimize their perception of emotional or psychological abuse.35

To examine the effects of Emotional Focused Intervention on the elderly couples with experience of emotionally abusive behaviors, it was not initially clear to what extent changes in emotional abuse would be formed, because there were some negative beliefs such as “changing the way elders think is impossible after 40 years,” and some expressions of disappointment such as “after 40 years of marriage, how can life change now?” Despite these superstitions, the findings were really surprising. It was revealed that the husbands’ and wives’ EAB significantly decreased at T2 and T3 compared with T1.Changes in EAB means after the intervention were greater among women than men due of the greater mean difference and effect size. In the control group, as well, a significant decrease in the wives’ EAB was found between T1 and T3 with a small mean difference and effect size. Although this change was very small, it should be interpreted with caution and considered in further research. The most probable explanation for this result is that the follow-up intervention took place in the month of Ramadan, the best month in the Islamic calendar. Emotionally abusive behaviors associated with violence, insults, threats, humiliation, and blame are condemned in Islam and the Holy Quran. Ramadan is the fasting month for Muslims, and fasting involves not only abstinence from eating and drinking (fasting for the body), but also from insults, threats, humiliation, blame, and ridicule (fasting for the soul). There is much evidence to confirm that the rates of crime and abuse behaviors significantly decrease during the month of Ramadan.36,37 Overall, the findings of the current study demonstrated that EAB significantly decreased after the intervention (T2, and T3) in the experimental group. Similarly, in an investigation, treatment outcomes of the couples’ group psycho-educational intervention were evaluated for 80 married distressed couples under 4 different conditions. The results revealed that friendship problems and destructive conflict significantly decreased, and marital satisfaction significantly increased under combined conditions at the one-year follow-up.38

The effects of the intervention on marital satisfaction revealed that the MS of both husbands and wives improved significantly three months after the intervention with a moderate effect size. However, husbands’ MS showed no significant change immediately after the intervention at T2. These values for the control group were not significant. In the same vein, the results of an investigation revealed that marital adjustment significantly enhanced by EFT.39 A recent study in Iran revealed that marital conflicts of couples who received 9 sessions of EFT significantly decreased compared with the control group.40 Although these studies were carried out on young or middle-aged couples, the current study also revealed a significant improvement in marital satisfaction in response to a significant decrease in EAB three months after the intervention. Johnson in an investigation on172 young couples revealed that lower levels of marital satisfaction were associated with higher levels of anger, contempt, and sadness.41 The results of the current study revealed that emotionally abusive behaviors significantly decreased in both husbands and wives after EFPEI. It seems that any decline in abusive behaviors such as contempt, hostility, intimidation, and humiliation led to improved marital satisfaction. The results of an investigation also revealed that negative verbal communication can indicate the worsening of relationship satisfaction, typically when there is a lack of positive effect on the couple.42 The results of the current study also showed a strong correlation between the husbands’ and wives’ emotionally abusive behaviors in older adults. There is no well-known mechanism to explain this relationship in emotional abuse; one possible clarification may be found in the theory of emotional contagion. This theory postulates that emotions are easily transferred to another person when two individuals are in an intimate interpersonal relationship.43 Therefore, one partner’s negative feeling significantly affects the marital relationship and predicts his or her spouse’s marital adjustment.44 These results confirm our findings that marital satisfaction will be improved by decreasing EAB.

The strength of this study was using block randomization to make an equal opportunity for all participants to share their experience of abusive relationship and prevent the bias selection. Moreover, the emotional focused psycho-educational intervention, which was applied in this study, was based on a strong theoretical framework. It was an effort to fill a gap in the present literature related to emotional focused interventions for older couples. Furthermore, active engagement of couples (both husbands and wives) in emotional focused intervention increases the possibility that intervention will be linked to the attachment needs of couples. Also, collaboration between clinician and professional nurses in community health, and geriatrics nurses who were expert in family counseling, and couple therapy in daily clinic centers for older people provided important information for screening and treating the older couples with abusive relationship.

There were also some limitations in this study. First, the couples who participated in this study were volunteers; therefore, they may not be representative of the general population in quest of help for treatment of emotional abuse relationship. The coincidence of Ramadan as a month of follow-up was the second limitation of this study, so the findings should be interpreted with caution and considered in further research.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, health care professionals can play a crucial role in the diagnosis and treatment of older couples who suffer from emotional abuse behaviors. EFPEI based on EFT-C is a proper treatment for decreasing emotional abuse behaviors and improving marital satisfaction among the married elderly couples. Moreover, for treatment of emotional abuse behaviors among the couples it is important that both husband and wife should be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article (grant no: 6507) has been extracted from Maryam Hazrati’s PhD Thesis of Gerontology in the University of Putra Malaysia. Special thanks are due to authorities of Shiraz University of Medical Science who supported this project, as well as the elderly couples who helped us carry out this research.

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

REFRENCES

- 1.Black M, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liles S, Usita P, Irvin VL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among young, middle, and older women of Korean descent in California. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:801–11. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9471-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shams Esfandabadi H, Emamipoor S. Spouse abuse prevalence and its determinants. Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2003;5:59–82. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seyfrabiei MA, Ramezani Tehrani F, Hatmi ZN. Spouse abuse and its effective factors. Journal of Women’s Research. 2002;1:5–25. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Aghahoseini S. The evaluation of disability and its related factors among the elderly population in Kashan, Iran. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondodyer C, Connolly MT. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandl B, Horan DL. Domestic violence in later life: an overview for health care providers. Women & Health. 2002;35:41–54. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mc Garry J, Simpson C, Hinchliff-Smith K. The impact of domestic abuse for older women: a review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2011;19:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL, Dunlop BD. Internal barriers to help seeking for middle-aged and older women who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2006;17:53–74. doi: 10.1300/j084v17n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL, Dunlop B. External barriers to help seeking for older women who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:747–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, et al. Intimate partner violence in older women. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:34–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritsch TA, Tarima SS, Caldwell GG, Beaven S. Intimate partner violence against older women in Kentucky. The Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2005;103:461–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouton CP. Intimate partner violence and health status among older women. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1465–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zink T, Fisher BS, Regan S, Pabst S. The prevalence and incidence of intimate partner violence in older women in primary care practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:884–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet. 2004;364:1263–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. The role of stalking in domestic violence crime reports generated by the Colorado Springs Police Department. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:427–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danis FS, Lockhart L. Guest editorial: Domestic violence and social work education: What do we know, what do we need to know? Journal of Social Work Education. 2003;39:215–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisner CL, Gilmer TP, Saltzman LE, Zink TM. Intimate partner violence against women do victims cost health plans more? Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48:439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher BS, Regan SL. The extent and frequency of abuse in the lives of older women and their relationship with health outcomes. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:200–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straka SM, Montminy L. Responding to the needs of older women experiencing domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:251–67. doi: 10.1177/1077801206286221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamdan-Mansour AM, Arabiat DH, Sato T, et al. Marital abuse and psychological well-being among women in the southern region of Jordan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2011;22:265–73. doi: 10.1177/1043659611404424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: a user–friendly guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:327–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noak J, Wright S, Sayer J, et al. The content of management of violence policy documents in United Kingdom acute inpatient mental health services. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37:394–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahangar K, Juhari R, Siti Nor Y, Abu Talib M. Demographic factors and marital satisfaction among Iranian married students in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities. 2016;5:153–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HK, McKenry PC. The relationship between marriage and psychological well-being alongitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:885–911. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amidu N, Owiredu WKBA, Gyasi-Sarpong CK, et al. Sexual dysfunction among married couples living in Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. BMC Urology. 2011;11:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepard MF, Campbell JA. The Abusive Behavior Inventory: A measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. British Medical Journal. 2010;340 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg LS, Johnson SM. Emotionally Focused Therapy for Couples. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynes SN, Floyd FJ, Lemsky C, et al. The marital satisfaction questionnaire for older persons. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:473–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Péloquin K, Lafontaine MF, Brassard A. A dyadic approach to the study of romantic attachment, dyadic empathy, and psychological partner aggression. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;28:915–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straus MA, Ramirez IL. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:281–90. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: a comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199–230. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hematti R. The effective factors on men’s violence against women: Case study of Tehran’s families. Social Welfare. 2004;313:227–56. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varia R, Abidin RR. The minimizing style: Perceptions of psychological abuse and quality of past and current relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:1041–55. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavakoli N. Effect of spirituality on decreasing crimes and social damages: a case study on Ramadan. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences. 2012;3:518–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Sobaye HBT. The Impact of Ramadan on the Rates of Crime in Saudi Arabia [Thesis] Saudi Arabia: Naif Arab University for Security Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babcock JC, Gottman JM, Ryan KD, Gottman JS. A component analysis of a brief psycho-educational couples’ workshop: One-year follow-up results. Journal of Family Therapy. 2013;35:252–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziyaolhagh MS, Hassanabadi H, Ghanbarihashemabadi B, Modares Gharavi M. The effect of emotionally-focused couple therapy on marital adjustment. Family Research. 2012;8:49–66. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmadi FS, Zarei E, Fallahchai SR. The effectiveness of emotionally-focused couple therapy in resolution of marital conflicts between the couples who visited the consultation centers. Journal of Educational and Management Studies. 2014;4:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson SM. Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy with Trauma Survivors: Strengthening Attachment Bonds. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punyanunt-Carter NM. Reported affectionate communication and satisfaction in marital and dating relationships. Psychological Reports. 2004;95:1154–60. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.3f.1154-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neumann R, Strack F. “Mood contagion”: the automatic transfer of mood between persons. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:211–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knabb JJ, Vogt RG. The relationship between personality and marital adjustment among distressed married couples seen in intensive marital therapy: An actor-partner interdependence model analysis. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2011;33:417–40. [Google Scholar]