Abstract

NQO1 (NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1) reduces quinones and xenobiotics to less-reactive compounds via 2-electron reduction, one feature responsible for the role of NQO1 in antioxidant defense in several tissues. In contrast, NADPH cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CYP450OR), catalyzes the 1-electron reduction of quinones and xenobiotics, resulting in enhanced superoxide formation. However, to date, the roles of NQO1 and CYP450OR in pancreatic β-cell metabolism under basal conditions and oxidant challenge have not been characterized. Using NQO1 inhibition, over-expression and knock out, we have demonstrated that, in addition to protection of β-cells from toxic concentrations of the redox cycling quinone menadione, NQO1 also regulates the basal level of reduced-to-oxidized nucleotides, suggesting other role(s) beside that of an antioxidant enzyme. In contrast, over-expression of NADPH cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CYP450OR) resulted in enhanced redox cycling activity and decreased cellular viability, consistent with the enhanced generation of superoxide and H2O2. Basal expression of NQO1 and CYP450OR was comparable in isolated islets and liver. However, NQO1, but not CYP450OR, was strongly induced in β-cells exposed to menadione. NQO1 and CYP450OR exhibited a reciprocal preference for reducing equivalents in β-cells: while CYP450OR preferentially utilized NADPH, NQO1 primarily utilized NADH. Together, these results demonstrate that NQO1 and CYP450OR reciprocally regulate oxidant metabolism in pancreatic β-cells.

Keywords: NQO1, CYP450OR, NAD(P)H, pancreatic β-cell, redox cycling, menadione

1. Introduction

NQO1 (NAD(P)H-dependent Quinone Oxidoreductase 1) is well known for its ability to provide protection against oxidative stress. In several tissues, namely the liver, kidney and lung, NQO1, a phase 2 enzyme, is induced in response to oxidative stress (Benson et al., 1980), and its expression is regulated by the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE pathway (Dinkova-Kostova and Talalay, 2010; Xie et al., 1995). NQO1 plays a key role in the metabolism and detoxification of quinones, natural as well as anthropogenic molecules with conjugated double bond system responsible for their ability to undergo intracellular redox cycling (Jaiswal, 2000), which generates superoxide and subsequently H2O2. In contrast to other oxidoreductases such as NADPH cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CYP450OR), which utilizes one-electron reduction to convert quinones into superoxide (O2·-)-producing semiquiones, NQO1 uses a 2-electron reduction mechanism to convert quinones into more stable quinols, which are subsequently conjugated and diverted to excretory pathways (Figure 1). NQO1 thus plays a basic role in cellular protection from toxicant stress as demonstrated by the decreased survival of NQO1 KO mice and their islets under exposure to toxic levels of menadione (Radjendirane et al., 1998; Yeo et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Role of NQO1 and CYP450OR in the redox cycling and metabolism of menadione.

CYP450OR supports the one-electron reduction of menadione to semi-quinone, which undergoes oxidation to regenerate the parent compound and superoxide. NQO1 supports the two-electron reduction of menadione to menadiol. Although menadiol can undergo redox cycling, it primarily undergoes enzymatic detoxification via glucuronidation by the kidney and excretion in the urine (Nishiyama et al., 2010; Nishiyama et al., 2008).

Studies which evaluate the role of NQO1 in the protection from oxidative stress in pancreatic β-cells are limited (Yeo et al., 2013). Various quinones (substrates for both NQO1 and CYP450OR), have been reported to modulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells and islets (MacDonald, 1991), however the mechanism of such action has not been fully elucidated. Pancreatic β-cells are especially prone to oxidant damage due to their relatively low level of H2O2-inactivating enzymes (Tiedge et al., 1997). This feature might facilitate the sensitivity of these cells to physiological levels of oxidant signaling (reviewed in (Newsholme et al., 2012)), however it backfires under nutritional or environmental stress, such as exposure to redox cycling compounds (Heart et al., 2012). Previous work in our laboratory demonstrated that the degree of redox cycling (determined as the level of H2O2 production) of menadione and many other quinones in INS-1 832/13 cells is positively correlated with the concentration of glucose. Unique to the pancreatic β-cell, the majority of glucose (the main fuel responsible for insulin secretion) undergoes oxidative catabolism, resulting in the formation of intracellular reducing equivalents NADH and NADPH, which serve as substrates for redox cycling (Heart et al., 2012). By metabolizing menadione and/or by altering the levels of reduced NADPH and NADH, NQO1 and CYP450OR could therefore have differential effects on β-cell survival and function.

Using pharmacological inhibition, over-expression and knockout, we utilized menadione, a prototypical redox cycling quinone and known chemical toxicant, to evaluate the role of NQO1 and CYP450OR in the regulation of β-cells redox homeostasis and survival. We have demonstrated that both NQO1 and CYP450OR regulate menadione-dependent H2O2 production by pancreatic β-cells and intact islets. NQO1 inhibition and knockout increased, while NQO1 over-expression decreased, respectively, menadione-dependent H2O2 production, and the level of menadione-dependent H2O2 production was inversely correlated with β-cell viability. In contrast, over-expression of CYP450OR increased menadione-dependent H2O2 production and decreased β-cell viability. These data support the important role of NQO1 in the protection of pancreatic β-cells from oxidative stress and suggest that NOQ1 and CYP450OR regulate redox cycling process in a reciprocal fashion in these cells.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Collagenase was from Roche, fetal calf serum was from Hyclone and Cell Titer Blue was from Promega. 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydrophenoxazine (AMPLEX-RED, cat #A12222) was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, New York). N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, cat #AC160280250) was purchased from Acros Organics (New Jersey). Horseradish peroxidase (cat #P-8125) and all other chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise specified.

Construction of adenoviruses

Recombinant, replication-deficient type 5 adenoviruses expressing human NQO1 and CYP450OR (plasmid constructs with human NQO1 and CYP450OR genes were purchased from Origene) were custom-constructed by Vector BioLabs (Philadelphia, PA): The expression of NQO1 and CYP450OR is under the control of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter that also directs expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the internal ribosome entry site. A control virus (CV) carrying only GFP was constructed in parallel. Viral titers were determined by the plaque formation assay.

INS-1 832/13 cell, HepG2 cells, and pancreatic islet preparation and culture

Clonal INS-1 832/13 cells, provided by Dr. Christopher Newgard (Duke University) were maintained and cultured as described previously (Hohmeier and Newgard, 2004). INS-1 832/13 cells are the most commonly used cell line to study pancreatic β-cell function, with many metabolic features comparable to those of primary rodent β-cells (Hohmeier et al., 2000). For NQO1 and CYP450OR over-expression studies, cells were infected at 60% confluency at 15-120 Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) and used 48 hours post-infection. HepG2 cells were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained and cultured according to ATCC protocols. Global NQO1 knockout (obtained from laboratory of Dr. Anil Jaiswal, who developed these mice (Radjendirane et al., 1998) and control (NQO1 wild type) male mice were used for pancreatic islet isolation. Animals were housed at the Marine Biological Laboratory Animal Care Facility with food and water available ad libitum with a 12 hr light:dark cycle. Following euthanasia with halothane, pancreatic islets were isolated from 3-4 months old control and global NQO1 knockout mice by collagenase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) digestion as previously described (Heart et al., 2009). After digestion and separation by histopaque gradient centrifugation, islets were hand-picked and used after an overnight culture in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone), penicillin/streptomycin and 5 mM glucose in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, or infected with adenoviruses at 50 MOI following immediately after the isolation. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Guidelines for Animal Care (IACUC) at the Marine Biological Laboratory and University of South Florida, in compliance with United States Public Health Service regulations.

2.4. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) assay

The Amplex Red/horseradish peroxidase assay was used to quantify the production of extracellular H2O2 both in intact cells and islets and in cellular lysates, as previously described with minor modifications. The lower limit of quantification of this method is 30 pmol/assay (Mishin et al., 2010).

Intact cells and islets

Cells, grown in 96-well plates to ∼80% confluency, or isolated islets following overnight culture, were pre-incubated for 1 hour in the Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) buffer (140 mM NaCl, 30 mM HEPES 7.4, 4.6 mM KCl,1 mM MgSO4, 0.15 mM Na2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2) with 3 mM glucose, and then exposed to reaction mixtures containing 25 μM Amplex Red and 1 U/ml horseradish peroxidase in KRB buffer, supplemented with indicated concentrations of glucose and indicated concentrations of the redox cycling compound menadione.

Cellular lysates

Cells were washed and suspended in KRB buffer and sonicated on ice with three 15-s pulses separated by 1 min of cooling. Cell lysates were centrifuged (3000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) to remove cellular debris. Cytosolic (supernatant) and mitochondrial (pellet) fractions were obtained following 10 min centrifugation at 12,000 × g. Protein aliquots (0.375 mg/mL) were supplemented with NADPH or NADH (0.5 mM). H2O2 formed by auto-oxidation of NADPH or NADH in the KRB buffer in the absence or presence of doxorubicin or menadione (10 μM) was subtracted from all measurements. The production of H2O2 was quantified by calculating the rate of fluorescence increase (540 nm excitation, 595 nm emission) due to H2O2-dependent conversion of Amplex Red to fluorescent Resorufin by horseradish peroxidase. Fluorescence was monitored using a SpectraMax M5 multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.5.1. NQO1 activity

Cells were washed twice with PBS, suspended in sonication buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 250 mM sucrose, and 50 μM FAD), and sonicated for 5 s on ice. Supernatants were collected following centrifugation (13 × g, 5 min) and analyzed for protein concentration. Assays were performed in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.7 mg/mL BSA, 250 mM sucrose, 0.2 mM NADPH, and 40μM dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) in the presence of 0.045 mg/mL of cell lysate protein and analyzed for the reduction of DCPIP measured at 600 nm for 60 s in a total reaction volume of 0.5 mL. The dicoumarol-inhibited activity representing NQO1 was converted to moles/min/mg protein using the molar extinction coefficient for DCPIP (21,000 M-1cm-1).

2.5.2. CYP450OR activity

Cells were washed twice with PBS, suspended in PBS, and sonicated for 5 s on ice. Supernatants were collected following centrifugation (13 × g, 5 min) and analyzed for protein concentration. Assays were performed in 273 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7), 0.09 mM EDTA, 30 μM cytochrome c, 90 μM NADPH, 0.004% (w/v bovine serum albumin) in the presence of 0.09 mg/mL cell lysate protein in a total reaction volume of 0.5 mL. CYP450OR activity, calculated as previously described (Masters et al., 1967), was determined by measuring absorbance for 120 s at 550 nm.

2.6. Determination of nucleotides

Adenine nucleotides were determined using the NAD+/NADH, and NADP+/NADPH kits (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) according to manufacturer protocols.

2.7. Quantitative real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TriReagent (Sigma) and reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) or the RTScript cDNA synthesis kit (Empirical Bioscience, Grand Rapids, MI)according to the manufacturers' protocols. Standard curves were generated using serial twofold dilutions from pooled cDNA samples to confirm > 90% reaction efficiency for each primer set. Real-time PCR was performed using Revaluation 2X QPCR master mix (Empirical Bioscience) on a MyIQ2 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). All PCR rimer sequences were generated using PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA)and verified using NCBI Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi). Primer sequences used were:

rat NQO1 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_017000.3): GGC CAT CAT TTG GGC AAG TCC ATT and ACT GAA AGC AAG CCA GGC AAA CTG; rat CYP450OR (NM_031576) GTG GCT GAA GAA GTG TCT CTA TT and GAT CTT GCT GAA CTC CGG TAT C; rat β-actin (NM_031144.3): TTG CTG ACA GGA TGC AGA AGG AGA and ACT CCT GCT TGC TGA TCC ACA TCT; mouse NQO1 (NM_008706.5): GAG AAG AGC CCT GAT TGT ACT G and ACC TCC CAT CCT CTC TTC TT; mouse CYP450OR (NM_008898.2): AGG CAC ATC CTA GCC ATT CTC CAA and ACT TCG CTT CAT ACT CCA CAG CCA; mouse β-actin (NM_007393.5): TTG CTG ACA GGA TGC AG GAT GGA AGA AAC GCC TGG AGA and GGC CCA CAG AAA GGC CAA ATT TCT; human CYP450OR (NM_000941.2):ACA ATG CCC AGG ACT TCT ACG ACT and TGG CAT TGA AGT GCT CGT AGG TCT; human β -actin (NM_001101.3): CTG GCA CCC AGC ACA ATG and GCC GAT CCA CAC GGA GTA CT.

2.8. Cell viability

Cell viability was measured by the reduction of Cell Titer Blue (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer protocol.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. For experiments involving one variable, significance was determined for multiple comparisons using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey Post-test (Neter et al., 1990). A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. For experiments involving two variables, significance was determined for multiple comparisons using two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons tests for planned comparisons (typically untreated or control virus treated samples, as mentioned in each figure) and multiplicity-adjusted p values (Wright, 1992).

3. Results

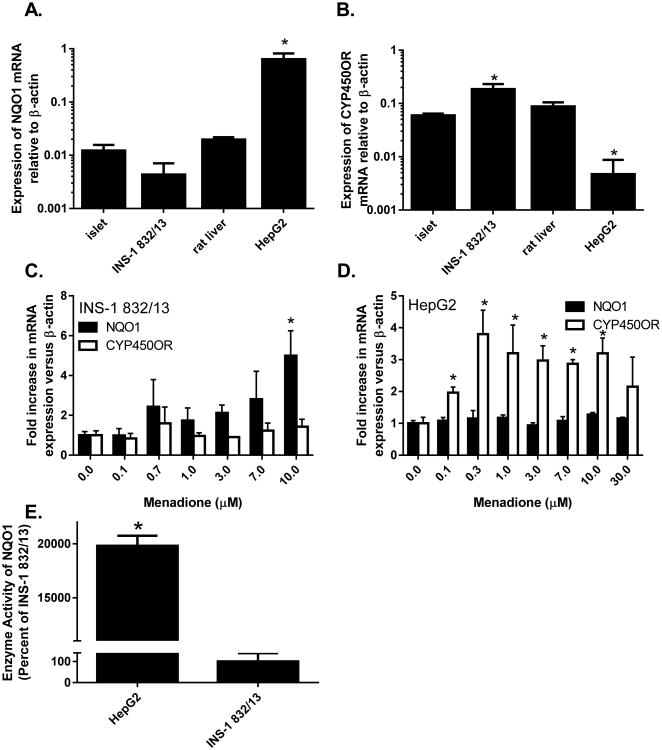

Both NQO1 and CYP450OR, enzymes involved in the metabolism of quinones and xenobiotics via 2- and 1-electron reductive schemes (Fig. 1), are expressed in rat clonal pancreatic β-cells and islets (Fig. 2). However, NQO1 mRNA expression and enzymatic activity are 150-fold and 200-fold lower, respectively, in INS-1 832/13 cells (Fig. 2A, 2B, and 2E) than in HepG2 cells (Fig. 2A, 2B, and 2E). Upon exposure to menadione, NQO1, but not CYP450OR, is induced in INS-1 832/13 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Basal expression and induction of NQO1 and CP450OR by menadione.

Relative abundance of NQO1 (A) and C (B) mRNA to the housekeeping gene β-actin. The induction of NQO1 and CYP450OR mRNA following 24 h treatment with menadione was determined in (C) INS-1 832/13 and (D) HepG2 cells. (E) Enzymatic activity of NQO1 in HepG2 and INS-1 832/13 cells was measured as described in Methods. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05 when comparing (A and B) mRNA expression in tissues or cell lines versus islets of Langerhans (1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test), (C and D) corresponding untreated control (2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test) or (E) expression versus INS-1 832/13 cells (2-sample t test).

To ascertain that the H2O2 produced by the menadione-dependent redox cycling inside the β cells is indeed the mediator of menadione-dependent loss of β-cell viability, INS-1 832/13 cells were subjected to co-treatment with antioxidant and H2O2 scavenger N-Acetyl cysteine (NAC). Indeed, NAC co-treatment protected cellular viability against menadione exposure in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) co-treatment protects against menadione toxicity in INS-1 832/13 cells.

The viability of INS-1 832/13 cells treated for 24 h with menadione in the presence or absence of various NAC concentrations was determined as described in Methods. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. p < 0.05 when comparing the (*) 0.025 mM concentration, (+) 0.05 mM concentration, or (Δ) 0.1 mM concentration against the 0 mM NAC untreated control using a 2-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test as described in the Methods.

To test the effect of intracellular NQO1 level on menadione-mediated redox cycling activity, NQO1 levels were modulated by adenoviral-mediated over-expression, pharmacological inhibition and knock out. Protein levels and enzymatic activities of NQO1 were measured following adenoviral infection and were correlated with adenoviral titers (Fig. 4A and 4B). NQO1 over-expression decreased menadione-dependent H2O2 production in INS-1 832/13 cells (Fig. 4C). This NQO1-depedent action was sensitive to the NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol, which enhanced menadione-dependent H2O2 production (Fig. 4D). Dicoumarol is traditionally used as an inhibitor of NQO1. Dicoumarol does not inhibit NQO2 (Long and Jaiswal, 2000), however concerns remain with its ability to inhibit other oxidoreductases and produce off-target effects such as mitochondrial uncoupling (Scott et al., 2011), albeit at concentrations which exceed those utilized in our study (Fig. 4D). Regardless, complementary experiments utilizing direct NQO1 over-expression and NQO1 KO islets were performed to verify dicoumarol-based findings as follows.

Figure 4. Effect of NQO1 overexpression or inhibition on redox cycling and cytotoxicity of menadione in INS-1 832/13 cells.

(A, B) Adenoviral-mediated over-expression of NQO1 increases (A) NQO1 protein and (B) NQO1 enzymatic activity. (C and D) The effect of NQO1 overexpression on the redox cycling-mediated generation of H2O2 by INS-1 832/13 cells was determined using Amplex Red as described in Methods. (D) The redox cycling of menadione in INS-1 832/13 cells was measured in the absence or presence of dicoumarol. (E) Redox cycling of menadione in NQO1 wild type or NQO1 KO islets was determined. (F) Effect of NQO1 overexpression on the viability of INS-1 832/13 cells following 24 h exposure to menadione was determined using Cell Titer Blue reduction as described in Methods. (G) Effect of NQO1 overexpression on the viability of INS-1 832/13 cells following 24 h exposure to H2O2, measured as in D.

(A) Western blot data are representative of three independent experiments, (B) enzymatic activity data are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate measurements. All remaining data (C-G) are representative of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate measurements. *p < 0.05 when compared with corresponding (B and C) CV-treated, (D) untreated, CV-treated or NQO1-treated, (E) 3 mM G or 16 mM G control, and (F and G) CV-treated. Statistical tests performed were (B) 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test or (C-G 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test).

MOI: multiplicity of infection, CV: control virus, 3G: 3 mM glucose (basal glucose), 16G: 16 mM glucose (stimulatory level of glucose for insulin secretion), DIC: Dicoumarol, DPI: Diphenyleneiodonium, NQO1 KO: NQO1 knock out.

Islets isolated from NQO1 KO mice exhibited an increased level of redox cycling activity and higher level of H2O2 production in response to menadione (Fig. 4E). Reciprocal to the effect of NQO1 on H2O2 production, NQO1 enhanced β-cell viability, as demonstrated by the enhanced viability in NQO1-over-expressing INS-1 832/13 cells treated with menadione (Fig. 4F).

To demonstrate that NQO1 protective action was indeed not due to the removal of H2O2 but rather due to the 2-electron reduction of menadione, we measured cell viability in QO1 over-expressing cells treated with H2O2. NQO1 over-expression did not protect against the loss of INS-1 832/13 cells viability due to the exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 4G).

In contrast to the NQO1-inhibitory action on menadione-dependent redox cycling activity, adenoviral-mediated over-expression of CYP450OR protein and enzymatic activity (Fig. 5A and B) paralleled the increase in redox cycling in INS-1 832/13 cells (Fig. 5C). Over-expression of CYP450OR was also correlated with greater susceptibility to menadione toxicity (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Effect of CYP450OR overexpression on the redox cycling and cytotoxicity of menadione in INS-1 832/13 cells.

(A, B) The effect of adenoviral-mediated CYP450OR over-expression on (A) CYP450OR protein and (B) CYP450OR enzymatic activity. (C) The effect of CYP450OR over-expression on the redox cycling-mediated generation of H2O2 by INS-1 832/13 cells was determined using Amplex Red as described in Methods. (D) Effect of CYP450OR over-expression on the viability of INS-1 832/13 cells following 24 h exposure to menadione was determined using Cell Titer Blue reduction as described in Methods. (A) Western blot data are representative of three independent experiments, (B) enzymatic activity data are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate measurements. All remaining data are representative of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicates. *p < 0.05 when compared with (B) CV-treated, (C) corresponding 3G (*) or 16G CV (+), or (D) CV-treated controls. Statistical tests performed were (B) 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test or (C-D) 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test.

CV: control virus, MOI: multiplicity of infection, 3G: 3 mM glucose, 16G: 16 mM glucose

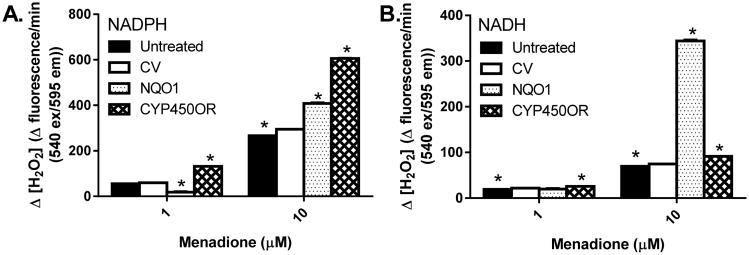

The redox cycling process is dependent upon the availability of cellular reduced equivalents, NADH and NADPH. NADPH is traditionally thought to be the primary intracellular electron donor for redox cycling; however, this has not been fully addressed, and certainly not for the redox cycling process in pancreatic β-cells. We therefore measured menadione-dependent redox cycling in vitro with cellular lysates from NQO1 and CYP450OR over-expressing cells, using NADH or NADPH as substrates (Fig. 6). Lysates from cells overexpressing CYP450OR preferentially utilized NADPH for redox cycling activity (Fig. 6A), whereas utilization of NADH remained negligible (Fig 6B). In contrast, lysates from NQO1 over-expressing cells utilized both NADPH and NADH, with a pronounced preference for NADH (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Redox cycling of menadione by INS-1 832/13 cellular lysates.

Cellular lysates, prepared from INS-1 832/13 cells (infected with NQO1 or CYP450OR adenoviruses at 60 MOI), were tested for the redox cycling of menadione in the presence of exogenous (A) NADPH or (B) NADH. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05 when compared with corresponding CV-treated controls using a 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test. CV: control virus

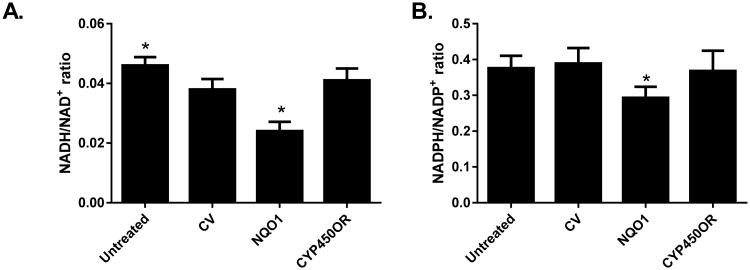

In untreated (in the absence of redox cycling compounds) INS-1 832/13 cells, NQO1, but not CYP450OR, modulated the reduced-to-oxidized ratios of nicotinamide dinucleotides. NQO1 over-expression decreased the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio and to a lesser degree the NADPH/NADP+ ratio (Fig. 7), consistent with the general role of NQO1 in cellular redox homeostasis.

Figure 7. Effect of NQO1 and CYP450OR over-expression on NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratio.

INS-1 832/13 cells were infected with NQO1 or CYP450OR adenoviruses at 60 MOI and NADH/NAD+ (A) and NADPH/NADP+ (B) ratios were determined following alkali extraction of cells 48 hours following infection, as described in Methods. Data are representative of three to four independent experiments performed in triplicate. *p < 0.05 when compared with corresponding CV-treated controls using a 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test. CV: control virus

4. Discussion

Exposure to quinones primarily occurs via both dietary and environmental routes. Naturally-occurring quinones, components of plants and bacteria, are consumed as part of the diet (Akagawa et al., 2015; Walther et al., 2013). Some of the plant-derived quinones have become popular as complementary therapies (Gray et al., 2016; Parmar et al., 2015; Tu et al., 2011) or commercially available drugs (Tobar et al., 2011). Examples of dietary quinones include phyloquinones, menaquinones (Walther et al., 2013), pyrroloquinoline quinone (Akagawa et al., 2015), rhein (Tobar et al., 2011), and thymoquinone (Gray et al., 2016). However, with the exception of the anthraquinone rhein (Tobar et al., 2011), the safety of quinone compounds, often taken as dietary supplements, has not been rigorously established and tested. Furthermore, synthetic quinones (such as p-benzoquinone) are used in the dye, textile, chemical, tanning, and cosmetic industries, where they are recognized to pose significant exposure risks (Sittig, 1985). Therefore, both dietary and environmental quinones, depending on their concentrations, have the potential to cause toxicity. Pancreatic β-cells, due to their low expression of H2O2-inactivating enzymes (Tiedge et al., 1997) combined with the highly vascularized nature of the pancreatic islet (Nikolova et al., 2006), are very vulnerable to toxicant insult, and their sensitivity to oxidants is well documented (reviewed in (Gray and Heart, 2010)). The relatively low basal NQO1 expression and activity may also contribute to the enhanced susceptibility of pancreatic β-cells to oxidative stress.

In the current work, we characterized the response of pancreatic β-cells to menadione, a prototypical, well-characterized redox cycling quinone, to investigate the potential effects of quinones on pancreatic β-cells. Following NAD(P)H-dependent enzymatic reduction, menadione undergoes spontaneous oxidation, regenerating the original compound and superoxide. Many enzymes are capable of supporting the redox cycling of menadione, including CYP450OR. CYP450OR reduces menadione to a semi-quinone radical, which subsequently auto-oxidizes to produce superoxide and menadione (Murataliev et al., 2004). Indeed, CHO cells overexpressing CYP450OR have increased toxicity in response to menadione treatment (Joseph et al., 2000). Menadione also causes the rapid depletion of glutathione in cells expressing CYP450OR (Morrison et al., 1985) and induces lipid peroxidation (Tampo and Yonaha, 1996). Finally, the semi-quinone form of menadione is capable of arylating cellular molecules, including DNA, and might therefore act as a mutagen (Watanabe and Forman, 2003).

Menadione is also reduced by NQO1; however, rather than being reduced to the semi-quinone, NQO1 catalyzes the full two electron reduction of menadione to menadiol (Fig. 1). In vivo, menadiol is quickly scavenged via phase II metabolism to produce a less toxic metabolite(s). NQO1 has been conclusively shown to be protective against menadione toxicity (Radjendirane et al., 1998). NQO1 is a gene target of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway, which is induced by prooxidants. Indeed, NQO1 was reported to be induced in human islets following their exposure to curcuminoids (Balamurugan et al., 2009). Several studies have investigated whether Nrf2 induction could protect islets from oxidative stress; the yield of healthy islets was higher in rats treated with the Nrf2 activator dh404 (Li et al., 2015), which also protected human islets against damage induced by H2O2 exposure and blunted the induction of inflammatory cytokines (Masuda et al., 2015). However, the role of NQO1 in protection of islets from oxidative stress following activation of Nrf2 cannot be decoupled from the action of other antioxidant enzymes induced by Nrf2 activators, such as HO-1. Menadione can also be reduced non-enzymatically through interaction with thiols, such as those found on cysteine or glutathione; (Chung et al., 1999). N-acetyl cysteine can also chemically react with H2O2, providing an alternative mechanism of protection (Arroub et al., 1994) at toxic concentrations of menadione.

In the current work, we examined the interplay between NQO1 and CYP450OR in the toxicity and metabolism of menadione in the pancreatic β-cell. Previous work by our laboratory demonstrated that menadione and quinones readily undergo redox cycling in both INS-1 832/13 cells and isolated islets in a glucose-dependent manner (Heart et al., 2012). Menadione induced cytotoxicity in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 for cell viability of ∼18 μM. Co-treatment with menadione and the antioxidant N-Acetyl cysteine (NAC) provided protection against menadione toxicity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3), consistent with NAC's role as a free radical scavenger (Aruoma et al., 1989).

We have demonstrated for the first time that NQO1 protects β-cells from menadione-induced cellular toxicity (Fig. 4F), by lowering the level of menadione-dependent H2O2 production (Fig. 4C-4F) likely via diversion of menadione to the 2-electron reduction route and subsequent metabolism as occurs in other cell types (Fig. 1) (Nishiyama et al., 2008). Indeed, the affinity of NQO1 for menadione has been shown to be higher than affinity of CYP450OR for this compound (Thor et al., 1982), potentially offsetting the 10-fold difference in expression favoring CYP450OR in isolated rat hepatocytes. These data suggest that flux via NQO1 is the rate-limiting step in menadione detoxification in pancreatic β-cells, as over-expression of NQO1 reduced both redox cycling and toxicity induced by menadione in these cells. This contrasts with previous work in CHO cells, where overexpression of NQO1 did not provide additional protection from menadione (De Haan et al., 2002). This led to the conclusion that NQO1 provided protection only to a particular threshold concentration, and that expression above that concentration did not provide additional protection; CHO cells endogenously expressed NQO1 at a level above the critical threshold, and thus were not protected by additional expression of NQO1 enzyme beyond that level. Here we conclude that INS-1 832/13 cells do not endogenously express NQO1 at a level beyond this threshold, which is consistent with low basal level of NQO1 protein and activity in these cells (Fig. 2) and (Fig. 4A and 4B). In contrast NQO1's ability to decrease redox cycling and increase cell viability (Fig. 4 B-E), CYP450OR acts in a reciprocal fashion, increasing redox cycling (Fig. 5C) and reducing cellular viability under menadione exposure (Fig. 5D).

Because both NQO1 and CYP450OR utilize NAD(P)H during the process of redox cycling (Fig. 1), their expression coupled with the presence of a redox cycling chemical has the potential to alter intracellular NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratios. In pancreatic β-cells, the reduced/oxidized adenine nucleotide ratios NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ play a special role in glucose metabolism; thus their regulation has the potential to affect glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). The NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratios increase following glucose elevation due to both glucose-dependent cataplerotic and anaplerotic pathways, the operation of which results in the production of ATP (Meglasson and Matschinsky, 1986) and other putative mediators of GSIS (Ivarsson et al., 2005; Kibbey et al., 2007; Leloup et al., 2011; Leloup et al., 2009; Maechler and Wollheim, 1999; Pi et al., 2007). NQO1 and CYP450OR displayed a significant difference in their preference for the utilization of cellular reduced equivalents. While CYP450OR almost exclusively used NADPH, consistent with its behavior in vitro (Sem and Kasper, 1993), NQO1 displayed strong preference for NADH in β-cells, similar to pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (Bongard et al., 2009).

However, even in the absence of menadione, NQO1 alters NADH (and to a lesser degree NADPH), as evidenced by the decreased NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratio in untreated NQO1 over-expressing cells. Our finding is in agreement with the reported elevated NADH and NADPH levels in the liver and fat of NQO1 KO mice and decreased NADH levels in NQO1 over-expressing neurons (Gaikwad et al., 2001; Hyun et al., 2012). NQO1-dependent utilization of NADH and NADPH is consistent with the role of NQO1 as a key member of plasma membrane electron transport system (PMET). PMET, an extramitochondrial pathway responsible for the re-oxidation of cytosolic reduced equivalents and for maintaining the reduced status of plasma membrane ubiquinone (Turunen et al., 2004), has been reported to operate in a variety of cells types (Del Principe et al., 2011) including those of pancreatic β-cells (Gray et al., 2011). The fact that NQO1 over-expression lowered the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 7) is significant because in β-cells, extracellular glucose is rapidly equilibrated across the plasma membrane via GLUT-2 transporter (Thorens et al., 1988), allowing the β-cell to function as an efficient extracellular glucose sensor (Schuit et al., 2001). Glucose metabolism generates NADH which must be promptly re-oxidized back to NAD+ in order to sustain glycolytic flux and downstream metabolic pathways leading to GSIS. NADH re-oxidation is enabled via mitochondrial shuttles, however also via operation of PMET. Our data demonstrating that NQO1 can lower the NADH/NAD+ ratio and our published findings that NQO1 over-expression enhances GSIS (Gray et al., 2011) are in support of this idea.

Taken together, our data show that differential expression of NQO1 and CYP450OR can influence the degree of redox cycling of menadione and consequently the overall toxicity resulting from exposure to this compound, with NQO1 being protective and CYP450OR being harmful. Furthermore, an alteration in expression of these enzymes alone affects levels of reducing equivalents, which has the potential to alter the primary function of β-cells, insulin secretion. Increased expression of NQO1 might therefore protect against menadione toxicity but also alter insulin secretion. Future studies are underway to fully elucidate the basic metabolic function of NQO1 in insulin secreting cells and its contribution to phase 2 metabolism in the β-cell.

Highlights.

NQO1 and CYP450OR reciprocally regulate menadione metabolism in pancreatic β-cells.

NQO1, but not CYP450OR, is induced in β-cells following exposure to menadione.

NQO1 directly regulates NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio in pancreatic β -cells.

Acknowledgments

Christopher Benton and Malcolm Johns are thanked for donation of a PCR machine and other equipment via the Department of Homeland Security Homeland Defense Equipment Reuse (HDER) program to support Cadet research at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy (JG). Shpetim Karandrea was supported by the Graduate Student Success Fellowship (University of South Florida). We are forever indebted to the intellectual input of the late Prof. M. Meow and Prof. L. Dracek for their relentless support in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors thank Xiaomei Liang, Carolyn Smith and Tasha Bull for their assistance in the laboratory and Gregory Hall for his help with statistical analysis. Joshua Gray is a Professor at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. The views presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Academy or other branches of the U.S. government.

Financial support: The work was supported by NIH R01DK098747 and American Diabetes Association grant # 7-12-BS-073 (EH).

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akagawa M, Nakano M, Ikemoto K. Recent Progress in Studies on the Health Benefits of Pyrroloquinoline Quinone. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;80:13–22. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1062715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroub J, Bergès J, Abedinzadeh Z, Langlet J, Gardès-Albert M. On N-Acetylcysteine. Part 1. Experimental and Theoretical Approaches of the N-Acetylcysteine/H2o2 Complexation. Can J Chem. 1994;72:2094–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The Antioxidant Action of N-Acetylcysteine: Its Reaction with Hydrogen Peroxide, Hydroxyl Radical, Superoxide, and Hypochlorous Acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan AN, Akhov L, Selvaraj G, Pugazhenthi S. Induction of Antioxidant Enzymes by Curcumin and Its Analogues in Human Islets: Implications in Transplantation. Pancreas. 2009;38:454–460. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318196c3e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AM, Hunkeler MJ, Talalay P. Increase of Nad(P)H:Quinone Reductase by Dietary Antioxidants: Possible Role in Protection against Carcinogenesis and Toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:5216–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongard RD, Lindemer BJ, Krenz GS, Merker MP. Preferential Utilization of Nadph as the Endogenous Electron Donor for Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1) in Intact Pulmonary Arterial Endothelial Cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Chung SM, Lee JY, Kim SR, Park KS, Chung JH. The Biological Significance of Non-Enzymatic Reaction of Menadione with Plasma Thiols: Enhancement of Menadione-Induced Cytotoxicity to Platelets by the Presence of Blood Plasma. FEBS Lett. 1999;449:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haan LH, Boerboom AM, Rietjens IM, van Capelle D, De Ruijter AJ, Jaiswal AK, Aarts JM. A Physiological Threshold for Protection against Menadione Toxicity by Human Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase (Nqo1) in Chinese Hamster Ovary (Cho) Cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:1597–1603. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Principe D, Avigliano L, Savini I, Catani MV. Trans-Plasma Membrane Electron Transport in Mammals: Functional Significance in Health and Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2289–2318. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Nad(P)H:Quinone Acceptor Oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1), a Multifunctional Antioxidant Enzyme and Exceptionally Versatile Cytoprotector. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaikwad A, Long DJ, 2nd, Stringer JL, Jaiswal AK. In Vivo Role of Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1) in the Regulation of Intracellular Redox State and Accumulation of Abdominal Adipose Tissue. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22559–22564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JP, Eisen T, Cline GW, Smith PJ, Heart E. Plasma Membrane Electron Transport in Pancreatic Beta-Cells Is Mediated in Part by Nqo1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E113–121. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00673.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JP, Heart E. Usurping the Mitochondrial Supremacy: Extramitochondrial Sources of Reactive Oxygen Intermediates and Their Role in Beta Cell Metabolism and Insulin Secretion. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2010;20:167–174. doi: 10.3109/15376511003695181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JP, Zayasbazan Burgos D, Yuan T, Seeram N, Rebar R, Follmer R, Heart EA. Thymoquinone, a Bioactive Component of Nigella Sativa, Normalizes Insulin Secretion from Pancreatic Beta-Cells under Glucose Overload Via Regulation of Malonyl-Coa. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;310:E394–E404. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00250.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart E, Cline GW, Collis LP, Pongratz RL, Gray JP, Smith PJ. Role for Malic Enzyme, Pyruvate Carboxylation, and Mitochondrial Malate Import in Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E1354–1362. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90836.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart E, Palo M, Womack T, Smith PJ, Gray JP. The Level of Menadione Redox-Cycling in Pancreatic Beta-Cells Is Proportional to the Glucose Concentration: Role of Nadh and Consequences for Insulin Secretion. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;258:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of Ins-1-Derived Cell Lines with Robust Atp-Sensitive K+ Channel-Dependent and -Independent Glucose- Stimulated Insulin Secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB. Cell Lines Derived from Pancreatic Islets. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun DH, Kim J, Moon C, Lim CJ, de Cabo R, Mattson MP. The Plasma Membrane Redox Enzyme Nqo1 Sustains Cellular Energetics and Protects Human Neuroblastoma Cells against Metabolic and Proteotoxic Stress. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:359–370. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9245-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson R, Quintens R, Dejonghe S, Tsukamoto K, in 't Veld P, Renstrom E, Schuit FC. Redox Control of Exocytosis: Regulatory Role of Nadph, Thioredoxin, and Glutaredoxin. Diabetes. 2005;54:2132–2142. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal AK. Regulation of Genes Encoding Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:254–262. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph P, Long DJ, 2nd, KleinSzanto AJ, Jaiswal AK. Role of Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (Dt Diaphorase) in Protection against Quinone Toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibbey RG, Pongratz RL, Romanelli AJ, Wollheim CB, Cline GW, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial Gtp Regulates Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion. Cell Metab. 2007;5:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup C, Casteilla L, Carriere A, Galinier A, Benani A, Carneiro L, Penicaud L. Balancing Mitochondrial Redox Signaling: A Key Point in Metabolic Regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:519–530. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup C, Tourrel-Cuzin C, Magnan C, Karaca M, Castel J, Carneiro L, Colombani AL, Ktorza A, Casteilla L, Penicaud L. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Are Obligatory Signals for Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:673–681. doi: 10.2337/db07-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Vaziri ND, Masuda Y, Hajighasemi-Ossareh M, Robles L, Le A, Vo K, Chan JY, Foster CE, Stamos MJ, Ichii H. Pharmacological Activation of Nrf2 Pathway Improves Pancreatic Islet Isolation and Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2015;24:2273–2283. doi: 10.3727/096368915X686210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DJ, 2nd, Jaiswal AK. Nrh:Quinone Oxidoreductase2 (Nqo2) Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MJ. Stimulation of Insulin Release from Pancreatic Islets by Quinones. Biosci Rep. 1991;11:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01182485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P, Wollheim CB. Mitochondrial Glutamate Acts as a Messenger in Glucose-Induced Insulin Exocytosis. Nature. 1999;402:685–689. doi: 10.1038/45280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters BSS, Williams CH, Kamin H. [92] the Preparation and Properties of Microsomal Tpnh-Cytochrome C Reductase from Pig Liver. Methods in Enzymology. 1967;10:565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y, Vaziri ND, Li S, Le A, Hajighasemi-Ossareh M, Robles L, Foster CE, Stamos MJ, Al-Abodullah I, Ricordi C, Ichii H. The Effect of Nrf2 Pathway Activation on Human Pancreatic Islet Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meglasson MD, Matschinsky FM. Pancreatic Islet Glucose Metabolism and Regulation of Insulin Secretion. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1986;2:163–214. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishin V, Gray JP, Heck DE, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Application of the Amplex Red/Horseradish Peroxidase Assay to Measure Hydrogen Peroxide Generation by Recombinant Microsomal Enzymes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1485–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison H, Di Monte D, Nordenskjold M, Jernstrom B. Induction of Cell Damage by Menadione and Benzo(a)Pyrene-3,6-Quinone in Cultures of Adult Rat Hepatocytes and Human Fibroblasts. Toxicol Lett. 1985;28:37–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murataliev MB, Feyereisen R, Walker FA. Electron Transfer by Diflavin Reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1698:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner M. Applied Linear Statistical Models. Irwin; Chicago: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Rebelato E, Abdulkader F, Krause M, Carpinelli A, Curi R. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species Generation, Antioxidant Defenses, and Beta-Cell Function: A Critical Role for Amino Acids. J Endocrinol. 2012;214:11–20. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova G, Jabs N, Konstantinova I, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Sorokin L, Fassler R, Gu G, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Melton DA, Lammert E. The Vascular Basement Membrane: A Niche for Insulin Gene Expression and Beta Cell Proliferation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Izawa T, Usami M, Ohnuma T, Ogura K, Hiratsuka A. Cooperation of Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 and Udp-Glucuronosyltransferases Reduces Menadione Cytotoxicity in Hek293 Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Ohnuma T, Inoue Y, Kishi T, Ogura K, Hiratsuka A. Udp-Glucuronosyltransferases 1a6 and 1a10 Catalyze Reduced Menadione Glucuronidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar MS, Syed I, Gray JP, Ray SD. Curcumin, Hesperidin, and Rutin Selectively Interfere with Apoptosis Signaling and Attenuate Streptozotocin-Induced Oxidative Stress-Mediated Hyperglycemia. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2015;12:363–374. doi: 10.2174/1567202612666150812150249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi J, Bai Y, Zhang Q, Wong V, Floering LM, Daniel K, Reece JM, Deeney JT, Andersen ME, Corkey BE, Collins S. Reactive Oxygen Species as a Signal in Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion. Diabetes. 2007;56:1783–1791. doi: 10.2337/db06-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radjendirane V, Joseph P, Lee YH, Kimura S, Klein-Szanto AJ, Gonzalez FJ, Jaiswal AK. Disruption of the Dt Diaphorase (Nqo1) Gene in Mice Leads to Increased Menadione Toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7382–7389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit FC, Huypens P, Heimberg H, Pipeleers DG. Glucose Sensing in Pancreatic Beta-Cells: A Model for the Study of Other Glucose-Regulated Cells in Gut, Pancreas, and Hypothalamus. Diabetes. 2001;50:1–11. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KA, Barnes J, Whitehead RC, Stratford IJ, Nolan KA. Inhibitors of Nqo1: Identification of Compounds More Potent Than Dicoumarol without Associated Off-Target Effects. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sem DS, Kasper CB. Interaction with Arginine 597 of Nadph-Cytochrome P-450 Oxidoreductase Is a Primary Source of the Uniform Binding Energy Used to Discriminate between Nadph and Nadh. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11548–11558. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittig M. Handbook of Toxic and Hazardous Chemicals and Carcinogens. Noyes Publications; Park Ridge, NJ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tampo Y, Yonaha M. Enzymatic and Molecular Aspects of the Antioxidant Effect of Menadione in Hepatic Microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:163–174. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor H, Smith MT, Hartzell P, Bellomo G, Jewell SA, Orrenius S. The etabolism of Menadione (2-Methyl-1,4-Naphthoquinone) by Isolated Hepatocytes. A Study of the Implications of Oxidative Stress in Intact Cells. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:12419–12425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorens B, Sarkar HK, Kaback HR, Lodish HF. Cloning and Functional Expression in Bacteria of a Novel Glucose Transporter Present in Liver, Intestine, Kidney, and Beta-Pancreatic Islet Cells. Cell. 1988;55:281–290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedge M, Lortz S, Drinkgern J, Lenzen S. Relation between Antioxidant Enzyme Gene Expression and Antioxidative Defense Status of Insulin-Producing Cells. Diabetes. 1997;46:1733–1742. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobar N, Oliveira AG, Guadagnini D, Bagarolli RA, Rocha GZ, Araujo TG, Santos-Silva JC, Zollner RL, Boechat LH, Carvalheira JB, Prada PO, Saad MJ. Diacerhein Improves Glucose Tolerance and Insulin Sensitivity in Mice on a High-Fat Diet. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4080–4093. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu T, Giblin D, Gross ML. Structural Determinant of Chemical Reactivity and Potential Health Effects of Quinones from Natural Products. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1527–1539. doi: 10.1021/tx200140s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and Function of Coenzyme Q. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther B, Karl JP, Booth SL, Boyaval P. Menaquinones, Bacteria, and the Food Supply: The Relevance of Dairy and Fermented Food Products to Vitamin K Requirements. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:463–473. doi: 10.3945/an.113.003855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Forman HJ. Autoxidation of Extracellular Hydroquinones Is a Causative Event for the Cytotoxicity of Menadione and Dmnq in A549-S Cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;411:145–157. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00716-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SP. Adjusted P-Values for Simultaneous Inference. Biometrics. 1992;48:1005–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Belinsky M, Xu Y, Jaiswal AK. Are- and Tre-Mediated Regulation of Gene Expression. Response to Xenobiotics and Antioxidants. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6894–6900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo SH, Noh JR, Kim YH, Gang GT, Kim SW, Kim KS, Hwang JH, Shong M, Lee CH. Increased Vulnerability to Beta-Cell Destruction and Diabetes in Mice Lacking Nad(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1. Toxicol Lett. 2013;219:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]