Abstract

Background

Despite success of public health-oriented tobacco control programs in lowering the smoking prevalence over the past several decades, it is unclear whether similar reductions in smoking have been experienced among pregnant women, especially in vulnerable groups such as those with major depression and/or lower socioeconomic status.

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between major depressive episode (MDE) and smoking among pregnant women overall, and by demographics and to estimate changes in the prevalence of cigarette smoking among pregnant women with and without MDE from 2005–2014.

Study Design

Cigarette use among pregnant women with and without MDE was examined using logistic regression models in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Results

Prenatal smoking is more common among pregnant women with, compared to without, MDE (32.5% vs. 13.0%; (adjusted OR=2.50 (1.85, 3.40)), and greater disparities were revealed when also considering income, education and race. Over time, smoking during pregnancy increased significantly among women with MDE (35.9% to 38.4%; p=0.02)) and showed a decreasing trend among women without MDE (12.5% to 9.1%; p=0.07) from 2005–2014.

Conclusions

Over the past decade, smoking during pregnancy has increased among women experiencing a major depressive episode and is over four times more common among pregnant women with, than without, MDE. Disparities in smoking during pregnancy by MDE status and socioeconomic subgroups appear substantial. Given the multitude of risks associated with both MDE and smoking during the prenatal period, more work targeting this vulnerable and high-risk group is needed.

Keywords: Depression, disparities, epidemiology, pregnancy, prenatal tobacco use

1. Introduction

Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with a wide variety of adverse outcomes in neonates and infants that span the life course. Compared with unexposed infants, those who are exposed have an elevated risk for sudden infant death (Hutchison et al., 2006), intrauterine growth retardation (Andres and Day, 2000), a 180–250g decrement in birth weight (Visscher et al., 2003), neurological and language problems (Fried, 1993), difficult temperament (Brook et al., 1998), aggression (Tremblay et al., 2004), behavioral and conduct problems (Monuteaux et al., 2006), deficit in attention and cognitive function (Naeye and Peters, 1984), attention deficit disorder (Button et al., 2005), early onset delinquent/antisocial problems (Wakschlag et al., 2003), later cigarette use (Buka et al., 2003), and increased substance use (Fergusson et al., 1998). Depression is strongly linked with cigarette use and nicotine dependence in the general population (Goodwin et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2012; Weinberger et al., 2016) and adults with depression have smoking rates up to 2–3 times higher than those without depression (Zvolensky et al., 2015). A number of studies have recently suggested that smoking both during pregnancy and postnatally (Grover et al., 2012) are higher among women with mental health conditions compared to women without mental health problems (Goodwin et al., 2007). Recent studies also suggest that maternal depression during pregnancy is independently associated with risks to mental and physical health outcomes in offspring (Latendresse et al., 2015; Nkansah-Amankra and Tettey, 2015; Plant et al., 2016; Plant et al., 2015). Pregnant women with depression are also more likely to continue smoking in pregnancy than those without depression (Smedberg et al., 2014). Fewer than half of pregnant women are routinely screened for depression (Venkatesh et al., 2016b), although depression can be screened and treated effectively during pregnancy. If pregnant women with depression have higher levels of prenatal smoking, they would constitute an important high-risk group to identify early in prenatal care to reduce long-term smoking-related adverse maternal and infant outcomes. As such, understanding the relationship between depression and prenatal smoking has tremendous clinical and public health implications to improve overall health.

Despite success of public health-oriented tobacco control programs that have led to substantial declines in smoking prevalence over the past several decades, whether similar reductions in smoking have been experienced among pregnant women is unclear. Recent analyses suggest that declines in smoking have not been distributed equally among subgroups of the population. At least two recent studies found that individuals with mental health problems may not have experienced as steep declines in smoking as the general population (Cook et al., 2014; Lawrence and Williams, 2016). The extent to which public tobacco control programs have had similar reductions in smoking among pregnant women, with and without depression, is unknown.

Pregnant women with depression may be a particularly vulnerable group, especially in need of smoking cessation interventions. There is evidence that smoking during pregnancy is more common among particular groups of women including younger women and women with lower SES profiles (Sirvinskiene et al., 2016). The extent to which these vulnerabilities, depression and low SES, may contribute jointly to an increase in prenatal smoking is not known. There is a need to examine subgroups of pregnant women to identify high-risk groups and determine modifiable risk factors to develop targeted smoking cessation intervention messages.

Depression is a prevalent but very treatable condition and has deleterious effects particularly for both pregnant women and their infants (Grote et al., 2010). Despite the public health significance, depression during pregnancy has received very little public health attention, and although the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology promote depression screening during pregnancy, very few pregnant women are routinely screened (SAMHSA, 2005). The current study begins to address the gap in understanding the role of depression in smoking during pregnancy. The goals of this study are fourfold. First, we investigate the relationship between depression and cigarette smoking among pregnant women in the United States. Second, we estimate the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women with and without depression from 2005–2014. Third, we examine the change in the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women who are depressed, compared with those not depressed, from 2005–2014. Fourth, we explore the relationship between depression and cigarette smoking, by important demographic characteristics, among pregnant women in the United States.

2. Methods

2.1 Data and Population

Data were drawn from the public-use data files from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) years 2005–2014. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) provides annual cross-sectional national data on the use of tobacco, other substances, and mental health in the U.S., as described elsewhere (SAMHSA, 2014). For this study, analyses were restricted to female respondents who reported being pregnant at the time of the interview (N=8721). Of these, 208 (2.4%) were excluded based on their reported smoking information (see below) or due to missing data on past year depression. This resulted in a total study population of N=8513.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Past Year Depression

Depression was assessed among NSDUH respondents based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edition (APA, 1994) criteria for major depressive episode (MDE). Separate modules were administered to adults (ages 18+) and to youth (ages 12–17). Details on the modules and the definitions for depression classifications are available (SAMHSA, 2014). Briefly, the modules were adapted from the depression sections of the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication and the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Respondents were classified as having had a lifetime MDE based on reporting 5+ out of 9 symptoms for MDE during the same 2-week period in their lifetimes. Additionally, at least one of the symptoms must have been a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities. Respondents with a lifetime MDE were classified has having past year MDE if, during the past 12 months, they felt depressed or lost interest or pleasure in daily activities for a period of 2 weeks or longer, while also having at least three other symptoms for lifetime MDE. No exclusions were made for MDE caused by medical illness, bereavement, or substance use disorders. Due to questionnaire changes in 2008, adjusted versions of the past year MDE variables for adults were developed to allow comparisons across years 2005–2008 and later years. Details on the method used for adjusting these variables, which was based on a model including terms for the survey version, demographic characteristics, and interactions, is available (Aldworth, 2012).

For this study, we were interested in examining the relation between past year MDE and prenatal smoking and created a single dichotomous variable for past-year major depressive episode (y/n) combining the youth and adult variables according to the respondent’s age.

2.2.2 Cigarette Smoking

Pregnant women were categorized as current smokers if they: a) responded ‘yes’ to the question “During the past 30 days, have you smoked part or all of a cigarette?” and b) reported a lifetime use of 100 or more cigarettes. Otherwise pregnant women were classified as not current smokers. Pregnant women (n=139) who reported cigarette smoking in the past 30 days but fewer than 100 cigarettes used in their lifetime were excluded from analyses.

2.2.3 Covariates

The following demographic covariates were incorporated into these analyses to address potential confounding and to explore heterogeneity in the association between depression and smoking during pregnancy: respondent age, highest level of education, current marital status, current household income, race, and whether the respondent had other children age <18 in the home. Categorical measures were used for each covariate as shown in Table 1. Respondents with ages<=14 or <18 were categorized as having been never married and having less than a high school education, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of U.S. pregnant women age 12+, overall and by the presence of past-year MDE, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2014

| Characteristic | Overall (N=8721) | With MDE (N=699; 6.7%)* | Without MDE (N=7950; 93.3%)* | p-value** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (s.e.) | % | (s.e.) | % | (s.e.) | ||

| Age | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 12–17 | 3.3 | (0.2) | 7.1 | (1.2) | 3.0 | (0.2) | |

| 18–25 | 36.8 | (0.8) | 44.2 | (2.6) | 36.3 | (0.8) | |

| 26–34 | 47.1 | (1.0) | 38.5 | (3.0) | 47.9 | (1.0) | |

| 35+ | 12.8 | (0.6) | 10.3 | (2.4) | 12.8 | (0.6) | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married | 59.8 | (0.9) | 44.7 | (2.9) | 61.0 | (1.0) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 6.2 | (0.4) | 9.4 | (1.5) | 5.8 | (0.5) | |

| Never married | 34.1 | (0.9) | 46.0 | (2.8) | 33.1 | (0.9) | |

| Education | 0.0009 | ||||||

| <High school | 19.3 | (0.5) | 23.7 | (2.1) | 18.7 | (0.6) | |

| High school graduate | 25.9 | (0.7) | 29.0 | (2.4) | 25.8 | (0.8) | |

| Some college | 24.2 | (0.8) | 26.7 | (2.5) | 24.2 | (0.8) | |

| College graduate or above | 30.6 | (1.0) | 20.6 | (2.8) | 31.4 | (1.0) | |

| Income | 0.0632 | ||||||

| <=$20,000 | 23.9 | (0.7) | 29.7 | (2.7) | 23.4 | (0.7) | |

| $20–49,999 | 31.7 | (0.8) | 31.6 | (2.4) | 31.7 | (0.9) | |

| $50–74,999 | 17.0 | (0.6) | 17.1 | (2.5) | 17.1 | (0.6) | |

| >=$75,000 | 27.4 | (0.9) | 21.6 | (2.8) | 27.9 | (0.9) | |

| Race | 0.0015 | ||||||

| White | 57.7 | (0.9) | 68.9 | (2.9) | 57.0 | (1.0) | |

| Black | 14.5 | (0.6) | 11.8 | (1.8) | 14.7 | (0.7) | |

| Hispanic | 19.7 | (0.7) | 15.0 | (2.1) | 19.9 | (0.8) | |

| Other | 8.1 | (0.5) | 4.3 | (0.9) | 8.3 | (0.6) | |

| Respondent has other children age <18 in the home | 0.0034 | ||||||

| No | 41.3 | (0.9) | 49.3 | (2.8) | 40.7 | (0.9) | |

| Yes | 58.7 | (0.9) | 50.7 | (2.8) | 59.4 | (0.9) | |

Unweighted N’s and population weighted percentages.

from chi-square tests for differences in characteristic distributions between women with and without past-year MDE.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

To describe the population, the frequencies of demographic characteristics among pregnant women overall and by past-year MDE status were calculated, and differences by MDE status were assessed using chi-squared tests.

To determine whether the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women changed over the 2005–2014 time period, and whether time trends varied depending on the presence of MDE, the annual prevalence of current smoking was calculated overall and by past-year MDE. Annual smoking prevalence estimates were calculated as the average marginal predictions from logistic regression models for current smoking, adjusted for covariates, with year included as a categorical predictor. To assess time trends, logistic regression models were fit using a linear term for calendar year, and year × MDE interaction. Thus, an odds ratio above 1.0 estimated from the coefficient for the linear year term indicates an increase in prevalence of smoking during pregnancy over the study period. Time was modeled using a linear term since the question of interest was whether an overall change in prenatal smoking had occurred over the study period, not necessarily during any one year. To assess annual differences in the relationship between MDE and smoking, MDE × (categorical) year product terms were added to the model with year as a categorical predictor, to produce year-specific odds ratios.

To determine whether MDE was associated with current smoking, logistic regression models were fit regressing current smoking status on past-year MDE, unadjusted and adjusted for demographic covariates and calendar year (categorical). Heterogeneity by important demographic characteristics was assessed and MDE × covariate product terms were added to the model to produce stratum-specific odds ratios and to test for interaction on the multiplicative scale.

All analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.1 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) and incorporated survey weights to account for the NSDUH complex sampling design. All results, other than raw counts, were adjusted for sampling weights.

3. Results

3.1 Major Depressive Episode and Smoking Among Pregnant Women in the United States

Among pregnant women, 6.7% (95% CI=6.0–7.5) were categorized as having an MDE. Pregnant women with MDE were more than twice as likely to be smokers during pregnancy than those without MDE (32.5% vs. 13.0%; covariate adjusted OR=2.50 (1.85, 3.40)).

3.2 Demographic Characteristics Among Pregnant Women with and without MDE in 2005–2014

Pregnant women with MDE were younger (p<0.0001), more likely to be widowed, separated, divorced or never married (p<0.0001), had lower levels of formal education (p=0.0009), lower income (p=0.06) and were more likely to be White (p=0.0015) than pregnant women without MDE (See Table 1). Pregnant women with MDE were also significantly more likely to have other children at home (under 18 years) than those without MDE (p=0.0034).

3.3 Smoking Among Pregnant Women from 2005 to 2014

The annual prevalence of current smoking among pregnant women is shown in Table 2. Overall, cigarette smoking declined among pregnant women (14.9% to 10.7%, p-value for trend=0.049) from 2005–2014, though this decline was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for demographic characteristics (p-value for trend=0.16).

Table 2.

Annual prevalence of current smoking among pregnant U.S. women age 12+, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2014

| Total | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (95%) |

||||||||||||

| Total sample (n) | 8582 | 909 | 889 | 942 | 948 | 935 | 884 | 817 | 766 | 746 | 746 | |

| Unadjustedc | ||||||||||||

| % | 14.40 | 14.87 | 16.78 | 13.74 | 15.62 | 12.23 | 18.89 | 14.97 | 12.28 | 13.78 | 10.67 | 0.97* (0.94, 1.00) |

| s.e. | 0.55 | 1.57 | 1.78 | 1.65 | 1.94 | 1.49 | 1.93 | 1.81 | 1.33 | 1.95 | 1.37 | |

| Adjustedd | ||||||||||||

| % | 14.40 | 15.03 | 15.89 | 13.81 | 15.06 | 12.38 | 17.21 | 14.70 | 12.84 | 14.44 | 12.03 | |

| Se | 0.55 | 1.32 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 1.39 | 1.71 | 1.42 | 1.03 | 1.92 | 1.41 |

Trends were assessed using logistic regression models for current smoking, with a linear term for the year. An odds ratio above 1.0 indicates an increase in current smoking over time, whereas an odds ratio below 1.0 indicates a decrease.

Adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, and race.

Prevalence estimates for current smoking were unadjusted for covariates but accounted for the complex survey design.

Average marginal predictions adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, and race with a categorical term for the year.

p=0.0499.

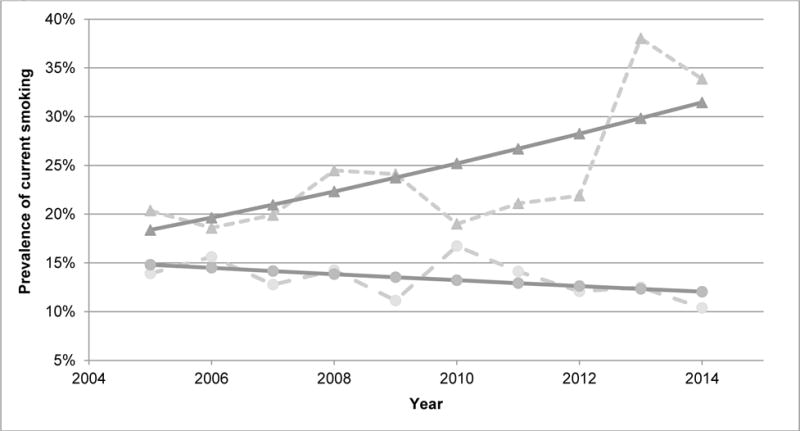

The annual prevalence of current smoking during pregnancy, stratified by past-year MDE, is shown in Table 3. Tests for heterogeneity in tends revealed significant differences in trends in the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women with and without MDE from 2005–2014, adjusting for demographics (t=2.84, p=0.005). Among pregnant women with MDE, the prevalence of smoking increased significantly during this period (adjusted OR=1.12 (1.02, 1.22; p=0.02) from 35.9% in 2005 to 38.4% in 2014 (See Figure 1 and Table 3)). However, the individual annual prevalence estimates should be interpreted with caution for this group given the relatively large standard errors (see Table 3). Among pregnant women without MDE, the prevalence of smoking declined from 12.5% to 9.05%, although the decreasing trend only approached statistical significance (adjusted OR=0.97 (0.93, 1.00; p=0.07)). The results were nearly identical when the analysis was restricted to pregnant women ages 18 and above.

Table 3.

Annual prevalence of current smoking among pregnant U.S. women age 12+, by the presence of past-year MDE, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2014

| Total | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Crude (95%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With MDE | ||||||||||||

| Total sample (n) | 687 | 104 | 71 | 86 | 81 | 71 | 50 | 67 | 57 | 53 | 47 | |

| Unadjustedc, % | 32.51 | 35.94 | 21.53 | 37.59 | 29.43 | 28.02 | 27.94 | 39.02 | 26.03 | 43.15 | 38.38 | 1.04 (0.95, p=0.40) |

| s.e. | 2.61 | 5.65 | 5.9 | 7.86 | 7.74 | 7.88 | 7.61 | 9.94 | 6.76 | 10.29 | 9.03 | |

| Adjustedd, % | 23.85 | 20.36 | 18.59 | 19.91 | 24.47 | 24.11 | 18.99 | 21.10 | 21.90 | 38.03 | 33.87 | |

| s.e. | 2.03 | 3.98 | 3.86 | 5.05 | 6.41 | 7.18 | 4.58 | 5.13 | 4.98 | 8.23 | 6.92 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Without MDE | ||||||||||||

| Total sample (n) | 7826 | 795 | 813 | 851 | 862 | 857 | 823 | 746 | 702 | 688 | 689 | |

| Unadjustedc, % | 13 | 12.48 | 16.46 | 11.55 | 14.61 | 10.8 | 17.88 | 13.65 | 11.37 | 11.88 | 9.05 | 0.97 (0.94, p=0.06) |

| s.e. | 0.59 | 1.5 | 1.98 | 1.62 | 2.01 | 1.42 | 2.05 | 1.83 | 1.46 | 1.91 | 1.46 | |

| Adjustedd, % | 13.43 | 13.90 | 15.62 | 12.77 | 14.24 | 11.14 | 16.72 | 14.12 | 12.08 | 12.50 | 10.38 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| P-value for heterogeneity in trend estimates for those with versus without MDE | 0.15 | |||||||||||

Trends were assessed using logistic regression models for current smoking, with a linear term for the year. An odds ratio above 1.0 indicates an increase in current smoking over time, whereas an odds ratio below 1.0 indicates a decrease.

Adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, and race.

Prevalence estimates for current smoking were unadjusted for covariates but accounted for the complex survey design.

Average marginal predictions adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, and race with a categorical term for the year.

Figure 1.

Annual prevalence of current smoking among pregnant U.S. women age 12+, by the presence of past-year major depressive episode (MDE), National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2014.

Estimates for women without MDE are indicated by circles and those for women with MDE are indicated by triangles. Estimates adjusted for demographic characteristics are shown in light gray (dashed lines). Adjusted estimates fit assuming linear trends over time are shown in dark gray (solid lines).

3.4 Temporal Relationship Between MDE and Smoking in Pregnant Women from 2005–2014

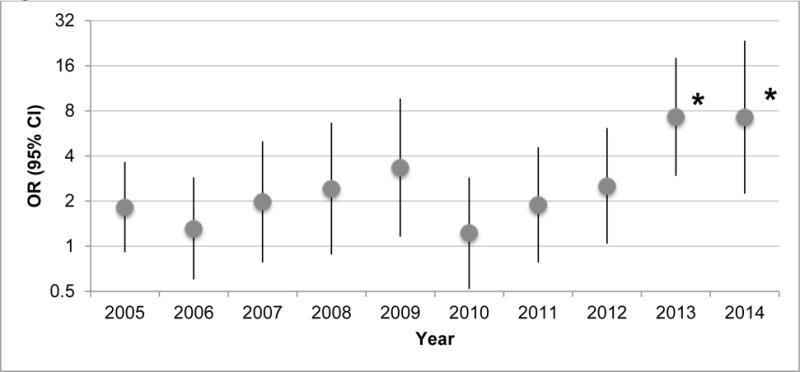

Additional analyses show that the strength of the odds ratio between MDE and smoking among pregnant women increased over time, from OR=1.82 (0.91, 3.65) in 2005 to 7.26 (2.24, 23.5) in 2014. The odds ratios for smoking associated with MDE were significantly higher in 2013 and 2014 relative to that in 2005 (See Figure 2; p-value for interaction (Pint)=0.049 for 2014 versus 2005).

Figure 2.

Adjusted annual odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for current smoking among pregnant women with versus without past-year major depressive episode, NSDUH 2005–2014. Asterisks indicate annual estimates that differ from the 2005 estimate at p<0.05.

3.5 Past-Year MDE and Smoking During Pregnancy, by Demographic Characteristics

Stratum-specific estimates for the association between current smoking and past-year MDE by demographic characteristics, and tests of heterogeneity between strata (p-values for interaction) are shown in Table 4. Below, we highlight key findings as a general description of the patterns present in the data; complete results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The prevalence of current smoking by past-year MDE status, and the odds ratio for the association of current smoking with past-year MDE among U.S. pregnant women age 12+, stratified by demographic characteristics, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2005–2014

| Unadjusted prevalence of smoking | Adjusted ORa, with versus without past year MDE | p-value, comparison of ORsb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With past-year MDE (N=687) |

No past-year MDE (N=7826) |

|||||

| % | s.e. | % | s.e. | (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | 32.5 | (2.6) | 13.0 | (0.6) | 2.50 (1.85, 3.40) | – |

| Age | ||||||

| 12–17 | 21.1 | (5.5) | 16.1 | (1.9) | 1.24 (0.63, 2.47) | 0.12 |

| 18–25 | 39.4 | (2.5) | 19.4 | (0.7) | 2.09 (1.53, 2.85) | 0.46 |

| 26–34 | 25.1 | (4.8) | 9.8 | (1.0) | 2.77 (1.45, 5.30) | Ref |

| 35+ | 37.3 | (11.8) | 6.3 | (1.4) | 8.93 (1.85, 43.03) | 0.17 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 21.9 | (3.6) | 6.5 | (0.6) | 3.33 (1.97, 5.63) | Ref |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 47.1 | (9.3) | 34.9 | (3.4) | 1.29 (0.49, 3.37) | 0.09 |

| Never married/<14 years old | 40.0 | (3.4) | 21.4 | (1.0) | 2.35 (1.63, 3.38) | 0.27 |

| Education | ||||||

| <High school or <18 years old | 43.0 | (5.3) | 22.3 | (1.5) | 1.92 (1.13, 3.25) | 0.01 |

| High school graduate | 36.9 | (5.5) | 19.9 | (1.2) | 1.97 (1.06, 3.64) | 0.02 |

| Some college | 33.9 | (5.4) | 13.3 | (1.3) | 2.88 (1.60, 5.21) | 0.06 |

| College grad or above | 13.1 | (5.2) | 1.8 | (0.5) | 7.96 (3.03, 20.94) | Ref |

| Income | ||||||

| <=$20,000 | 40.4 | (4.6) | 23.7 | (1.2) | 1.55 (0.94, 2.56) | 0.02 |

| $20–49,999 | 34.6 | (4.7) | 15.4 | (1.1) | 2.66 (1.78, 3.97) | 0.12 |

| $50–74,999 | 29.6 | (6.4) | 9.5 | (1.2) | 3.09 (1.31, 7.31) | 0.34 |

| >=$75,000 | 20.9 | (5.5) | 3.7 | (0.6) | 5.35 (2.34, 12.24) | Ref |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 40.1 | (3.2) | 17.2 | (0.9) | 2.71 (1.89, 3.90) | Ref |

| Black | 15.3 | (5.7) | 12.5 | (1.2) | 1.16 (0.49, 2.74) | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 12.5 | (4.0) | 3.4 | (0.7) | 3.59 (1.50, 8.58) | 0.54 |

| Other | 27.5 | (11.9) | 7.3 | (1.3) | 2.01 (0.73, 5.51) | 0.57 |

| Respondent’s other children in the home | ||||||

| No | 29.63 | (2.99) | 13.47 | (0.76) | 1.75 (1.17, 2.63) | Ref |

| Yes | 35.78 | (3.91) | 12.7 | (0.74) | 3.57 (2.38, 5.35) | 0.01 |

Stratum-specific estimates for the odds of current smoking among women with versus without past year MDE, adjusted for age, education, income, marital status, race, and calendar year (categorical). The model producing estimates stratified by respondent’s other children in the home was additionally adjusted for the respondent’s other children in the home.

P-values for heterogeneity between stratum-specific odd ratios and the odds denoted as the referent for each demographic characteristic. Assessed based on demographic characteristic × MDE product terms.

3.6 Education

There were significant differences by education level in the relationship between MDE and smoking in pregnancy (See Table 4). The relationship between MDE and smoking was significant among all education levels. The prevalence of smoking was inversely associated with the level of formal education among pregnant women both with and without past-year MDE. However, the relationship between MDE and smoking was strongest among those with a college degree or higher (OR=8.0 (3.0, 20.9)), compared with those who were high school graduates or less. This is partially due to the very low prevalence of smoking among the pregnant women without MDE in the highest (1.8%) versus the lowest (22.3%) education groups.

3.7 Income

The relationship between MDE and smoking in pregnancy was significant in all income strata except the lowest (<20k per year). Similar to education, the prevalence of prenatal smoking was inversely associated with income level among both pregnant women with and without past-year MDE. The strength of the association between MDE and smoking in pregnancy increased with increasing income strata. For example, the association between MDE and prenatal smoking among women in households with annual incomes of $75,000 or more (OR=5.4 (2.3, 12.2)) was significantly stronger than that among women from households with the lowest incomes (OR (95% CI)=1.6 (0.9, 2.6); Pint=0.02). However, it is important to note that the prevalence of prenatal smoking was much higher among pregnant women in the lower compared to higher income level group.

3.8 Marital Status

The association between MDE and smoking was marginally stronger (pint=0.09) among married (OR=3.3 (2.0, 5.6)) than among widowed, divorced, or separated women (OR=1.3 (0.5, 3.4)).

3.9 Race

The association between MDE and smoking was strongest among Hispanic women (OR=3.6 (1.5, 8.6)) and significant among both Hispanic and White women (OR=2.7 (1.9, 3.9)), while there was no significant relationship between MDE and smoking among pregnant Black women (OR=1.2 (0.5, 2.7)) or pregnant women in the Other Race group (OR=2.0 (0.7, 5.5)). Cell sizes were small in the “other” racial group which could account for the lack of significant finding although the difference in percentages was sizable (27.5% vs. 7.3%; See Table 4).

3.10 Age

There was no significant variation in the association between MDE and smoking among pregnant women by age (See Table 4).

3.11 Children in the Household

The association between MDE and smoking was highest among pregnant women with other children in the home (OR (95% CI)=3.6 (2.4, 5.4)); this relation was significantly stronger compared to women without other children in the home (OR (95% CI)=1.8 (1.2, 2.6); Pint=0.01).

4. Discussion

These findings suggest that, in the United States, pregnant women experiencing a major depressive episode within the past year have smoking rates nearly three times higher than those who have not experienced a past-year MDE. This disparity has increased significantly over the past 10 years—moving in the opposite direction from both national smoking trends and smoking trends among pregnant women without MDE. In 2014, nearly 40% of pregnant women with MDE smoked during pregnancy, compared with smoking among less than 10% of pregnant women without MDE; comparatively 35.9% of women with MDE smoked in pregnancy and 12.5% without MDE in 2005. The prevalence of smoking did not change significantly over time in the overall group of pregnant women, suggesting that current public health efforts have not been successful in reducing smoking rates in this group. The significant increase over time in smoking among pregnant women with MDE is even more concerning. Further, the prevalence of smoking varied widely depending on SES and MDE status. The size of these disparities is considerable, further highlighting the importance of focused efforts among vulnerable subgroups of pregnant women in need of targeted smoking cessation interventions and assistance. These findings and their implications for screening, treatment, prevention and research initiatives will be discussed below.

Overall, we found no significant decline in the prevalence of prenatal smoking over the 9-year period under investigation, consistent with other national reports on smoking during pregnancy. (Tong et al., 2013) Therefore, smoking rates have been stagnant among pregnant women in the US while a substantial decline in smoking has been witnessed in the general population over the same time period. Our study extends existing knowledge by showing that with stratification by major depressive episodes in the past year, smoking trends diverge and the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy among women with depression substantially and significantly increased, while the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women without MDE remained unchanged. The reasons for these diverging trends are presently unknown. One possibility is that national tobacco control campaigns that have been effective within the general population, such as public smoking bans and increased pricing, have not been effective in reducing smoking among pregnant women with MDE. From these findings, national and ongoing initiatives have not changed the smoking practices of pregnant women overall and most notably the smoking practices of pregnant women with MDE. Prior studies have suggested that broad national public smoking cessation programs do not similarly affect individuals with mental health problems, consistent with our findings (Cook et al., 2014).

Study results showed that depression is significantly linked with smoking during pregnancy among White and Hispanic women. This finding is somewhat in contrast to a prior regional study, in which an association between depression and increased prenatal smoking among black women was found in eastern North Carolina (Orr et al., 2005). This difference in findings may be related to sampling strategies. Ours was a nationally representative sample, since the North Carolina study focused on a single state, regional and environmental conditions, as well as the time/year difference, may have impacted these results. Of particular note, in the national sample, the highest percent of prenatal smoking overall was among White women, and 40% of White women with depression reporting smoking during pregnancy. More research is needed to determine racial disparities related to reasons for smoking during pregnancy in this group, to inform the development of more effective and targeted prevention and intervention efforts. In addition, we found that the relation between depression and smoking during pregnancy was significant among all education levels and strongest among women with a college degree or higher; this is contrary to findings relating maternal depression and continued smoking to be highest among women in the lowest educational stratum (Smedberg et al., 2015). We do note, however, that these educational differences are most likely related to the small number of smokers in the higher education group as reflected in the wide confidence intervals. Similarly, the relation between depression and prenatal smoking was strongest among women in the highest income strata primarily due to limited smoking among women without depression in the highest income group.

Additional study limitations are also noted. First, we did not have biochemical validation of cigarette use/abstinence, and therefore smoking may have been under-reported. (Dietz et al., 2011) However, given the strength of the relationships, our estimates of smoking are more likely conservative rather than an overestimate. Second, underreporting of smoking could have been differential between various demographic groups, in which the perception of social desirability may differ and therefore differentially influence reporting. Third, potential misclassification by timing imprecision is possible given that our measure of depression was over the past year and therefore possible that depression occurred prior to pregnancy.

In summary, in this large longitudinal national sample of pregnant women we found a significant relationship between depression and cigarette smoking, with a dramatic increase over time in the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women with depression. Given these findings, large-scale and targeted smoking cessation initiatives are needed. Depression is rarely screened for, detected or treated in pregnancy. Therefore, initiatives to increase routine and validated depression screening and treatment during prenatal care are needed. It is important to note that targeting the groups of pregnant women with the highest prevalence of prenatal smoking (i.e., low income women and women with a high school education or lower) may confer the largest overall benefit of depression screening and treatment to reduce prenatal smoking rates. In light of the risks associated with maternal mental health problems that can directly and indirectly harm the developing fetus, mounting evidence supports the importance of universal mental health screening in pregnancy. (Venkatesh et al., 2016a) Importantly, women with the highest levels of smoking (low education, low income and unmarried women) may be the least likely to be seen for early and routine prenatal care, therefore national, non-clinic based interventions for this group of pregnant women are needed. (Mohsin and Bauman, 2005) In fact, low-income women commonly have the lowest utilization of smoking cessation counseling services (Scheuermann et al., 2017) and interventions have been developed and evaluated to promote smoking cessation among pregnant women (Naughton et al., 2017). Most recently, smoking cessation interventions with a physical activity component targeting pregnant women have been suggested, interventions supplementing smoking cessation materials with text messaging, as well as broadening the scope of smoking screening programs to include general practitioners and obstetricians have been suggested (Giatras et al., 2017; Zeev et al., 2017; Naughton et al., 2017). Further, although smoking cessation in pregnancy has been associated with decreased depressive symptoms, implying a further benefit of large-scale smoking cessation programs, large-scale community-based trials that target depression reduction to improve smoking cessation rates among pregnant women at a population level have not been conducted (Munafo et al., 2008). Tailored, targeted and effective smoking cessation programs for pregnant women, with and without depression, need to be accessible and widely available, in and outside of prenatal care settings, to dramatically reduce prenatal smoking rates.

5. Public Health Implications

Pregnant women are a vulnerable population. In this large longitudinal national sample of pregnant women, we found a significant relationship between depression and cigarette smoking, with a dramatic increase over time in the prevalence of smoking among pregnant women with depression. Given these findings, large-scale and targeted smoking cessation initiatives for pregnant women with mental health problems are needed. Importantly, women with the highest levels of smoking (low education, low income and unmarried women) may be the least likely to be seen for early and routine prenatal care, therefore national, non-clinic based interventions for this group of pregnant women are needed.

Highlights.

The relationship between depression and cigarette smoking in pregnancy is estimated.

Logistic regression models in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health were used.

Smoking during pregnancy has increased in women with depression from 2005–2014.

Smoking is four times more common in pregnant women with than without depression.

Public health tobacco control programs must better target this demographic.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by a grant from NIDA/NIH to Dr. Goodwin (#DA02892). The funding source played no role in the analysis or interpretation of results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

RDG conceived of the study question and drafted the manuscript. MMW designed the statistical analyses. KCP conducted the analyses. DN, YN, DSH, PS and SG made critical contributions to the interpretation of results and co-writing the manuscript. All authors approved of the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Aldworth J, Kott P, Yu F, Mosquin P, Barnett-Walker K. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological Resource Book. RTI International; Research Triangle Park NC: 2012. Analysis of effects of 2008 NSDUH questionnaire cahnges: Methods to adjust adult MDE and SPD estimates and to estimate SMI in the 2005–2009 surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Andres RL, Day MC. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco use. Seminars in Neonatology. 2000:231–241. doi: 10.1053/siny.2000.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Shenassa ED, Niaura R. Elevated risk of tobacco dependence among offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy: A 30-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1978–1984. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button T, Thapar A, McGuffin P. Relationship between antisocial behaviour, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal prenatal smoking. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:155–160. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311:172–182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ, Burley K, Tong VT, Dube SR, Bernert JT. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:355–359. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:721–727. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA. Prenatal exposure to tobacco and marijuana: Effects during pregnancy, infancy, and early childhood. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 1993;36:319–337. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giatras N, Wanninkhof E, Leontowitsch M, Lewis B, Taylor A, Cooper S, Ussher M. Lessons learned from the London Exercise and Pregnant (LEAP) Smokers randomised controlled trial process evaluation: Implications for the design of physical activity for smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:85. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4013-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Keyes K, Simuro N. Mental disorders and nicotine dependence among pregnant women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:875–883. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255979.62280.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Pagura J, Spiwak R, Lemeshow AR, Sareen J. Predictors of persistent nicotine dependence among adults in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Zvolensky MJ, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Mental disorders and cigarette use among adults in the United States. Am J Addiction. 2012;21:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover KW, Zvolensky MJ, Lemeshow AR, Galea S, Goodwin RD. Does quitting smoking during pregnancy have a long-term impact on smoking status? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison L, Stewart A, Mitchell E. SIDS-protective infant care practices among Auckland, New Zealand mothers. N Z Med J. 2006:119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse G, Wong B, Dyer J, Wilson B, Baksh L, Hogue C. Duration of maternal stress and depression: Predictors of newborn admission to neonatal intensive care unit and postpartum depression. Nurs Res. 2015;64:331–341. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Williams JM. Trends in smoking rates by level of psychological distress-time series analysis of US national health interview survey data 1997–2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:1463–1470. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin M, Bauman AE. Socio-demographic factors associated with smoking and smoking cessation among 426,344 pregnant women in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monuteaux MC, Blacker D, Biederman J, Fitzmaurice G, Buka SL. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring overt and covert conduct problems: A longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Heron J, Araya R. Smoking patterns during pregnancy and postnatal period and depressive symptoms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1609–1620. doi: 10.1080/14622200802412895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeye RL, Peters EC. Mental development of children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:601–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton F, Cooper S, Foster K, Emery J, Leonardi-Bee J, Sutton S, Jones M, Ussher M, Whitemore R, Leighton M, Montgomery A, Parrott S, Coleman T. Large multicentre pilot randomised controlled trial testing a low-cost, tailored, self-help smoking cessation text message intervention for pregnant smokers (MiQuit) Addiction. 2017;112:1238–49. doi: 10.1111/add.13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra S, Tettey G. Association between depressive symptoms in adolescence and birth outcomes in early adulthood using a population-based sample. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr ST, Newton E, Tarwater PM, Weismiller D. Factors associated with prenatal smoking among black women in eastern North Carolina. Matern Child Healt J. 2005;9:245–252. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant DT, Pariante CM, Sharp D, Pawlby S. Maternal depression during pregnancy and offspring depression in adulthood: role of child maltreatment. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207:213–220. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.156620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant DT, Pawlby S, Sharp D, Zunszain PA, Pariante CM. Prenatal maternal depression is associated with offspring inflammation at 25 years: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e936. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2013. Codebook SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann TS, Richter KP, Jacobson LT, Shireman TI. Medicaid coverage of smoking cessation counseling and medication is underutilized for pregnant women. Nicotine Tob Research. 2017;19:656–659. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sirvinskiene G, Zemaitiene N, Jusiene R, Smigelskas K, Veryga A, Markuniene E. Smoking during pregnancy in association with maternal emotional well-being. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2016;52:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedberg J, Lupattelli A, Mardby AC, Nordeng H. Characteristics of women who continue smoking during pregnancy: A cross-sectional study of pregnant women and new mothers in 15 European countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedberg J, Lupattelli A, Mardby AC, Overland S, Nordeng H. The relationship between maternal depression and smoking cessation during pregnancy–A cross-sectional study of pregnant women from 15 European countries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Seguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, Perusse D, Japel C. Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:43–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh KK, Nadel H, Blewett D, Freeman MP, Kaimal AJ, Riley LE. Implementation of universal screening for depression during pregnancy: Feasibility and impact on obstetric care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016b;214:126. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher WA, Feder M, Burns AM, Brady TM, Bray RM. The impact of smoking and other substance use by urban women on the birthweight of their infants. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:1063–1093. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Middlecamp MK, Walton LL, Tenzer P, Leventhal BL. Pregnant smokers who quit, pregnant smokers who don’t: Does history of problem behavior make a difference? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2449–2460. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Kashan RS, Shpigel DM, Esan H, Taha F, Lee CJ, Funk AP, Goodwin RD. Depression and cigarette smoking behavior: A critical review of population-based studies. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1171327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeev YB, Bonevski B, Twyman L, Watt K, Atkins L, Palazzi K, Oldmeadow C, Gould GS. Opportunities missed: a cross-sectional survey of the provision of smoking cessation care to pregnant women by Australian general practitioners and obstetricians. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:636–641. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bakhshaie J, Sheffer C, Perez A, Goodwin RD. Major depressive disorder and smoking relapse among adults in the United States: a 10-year, prospective investigation. Psychiat Res. 2015;226:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]