Significance

We show how small-scale (less than millimeters2) neuronal dynamics relates to network activity observed across wide areas (greater than centimeters2) during certain network states, such as seizures. Simulations show how macroscopic network properties can affect frequency and amplitude of ictal oscillations. Additionally, the seizure dynamic suggests that one neuronal function, feedforward inhibition, plays different roles across scales: (i) inhibition at the small-scale wavefront fails, allowing seizure activity to propagate, but (ii) at macroscopic scales, inhibition of the surrounding territory is activated via long-range intracortical connections and creates a distinct pathway to a postictal state. Ultimately, our modeling framework can be used to examine meso- and macroscopic perturbations and evaluate strategies to promote transitions between ictal and nonictal network states.

Keywords: multiscale interactions, nonlinear dynamics, seizures, epilepsy, feedforward inhibition

Abstract

Small-scale neuronal networks may impose widespread effects on large network dynamics. To unravel this relationship, we analyzed eight multiscale recordings of spontaneous seizures from four patients with epilepsy. During seizures, multiunit spike activity organizes into a submillimeter-sized wavefront, and this activity correlates significantly with low-frequency rhythms from electrocorticographic recordings across a 10-cm-sized neocortical network. Notably, this correlation effect is specific to the ictal wavefront and is absent interictally or from action potential activity outside the wavefront territory. To examine the multiscale interactions, we created a model using a multiscale, nonlinear system and found evidence for a dual role for feedforward inhibition in seizures: while inhibition at the wavefront fails, allowing seizure propagation, feedforward inhibition of the surrounding centimeter-scale networks is activated via long-range excitatory connections. Bifurcation analysis revealed that distinct dynamical pathways for seizure termination depend on the surrounding inhibition strength. Using our model, we found that the mesoscopic, local wavefront acts as the forcing term of the ictal process, while the macroscopic, centimeter-sized network modulates the oscillatory seizure activity.

Functional interactions between single or small groups of nerve cells and large cortical networks are a critical frontier in neuroscience, especially in epilepsy research. For example, recent work using multiscale neocortical recordings in patients with epilepsy reports distinct activity patterns across scales (1–5), but the long-range effects from local neuronal activity on the genesis and evolution of seizures are still unknown.

In particular, ref. 2 presented evidence from microelectrode arrays (MEAs) that, during seizures, a wavefront of multiunit spike activity separates two territories with distinct neuronal activity: the core and penumbra. The core is defined by spiking activity that showed spatiotemporal organization related to the low-frequency component of the local field potential (LLFP; 2–50 Hz). The LLFP corresponds approximately to the “Berger bands” that compromise the clinically used EEG. In contrast, penumbral activity showed a lack of both spatial organization and correlation between spikes and local field potentials (LFPs) (2, 6). The propagating wave of intense spiking activity that separates the territories can be attributed to failed inhibitory restraint in the core (7, 8), presumably from paroxysmal depolarizations in the smaller inhibitory neurons (9). Recent work has shown evidence that epileptiform discharges take the form of traveling waves that move across the cortical surface at 0.2–0.3 m/s, similar to the velocity of unmyelinated axonal conduction, and originate from the ictal wavefront (1, 5, 10, 11). Given that the mesoscopic ictal wavefront and the macroscopic LLFP during seizure activity display a remarkable complex relationship, we were motivated to investigate how a small territory, the ictal core, exhibits long-range influences across a large network.

Computational models have been successfully applied to further our understanding of the dynamics during epileptiform activity (12–22), ranging from small-scale, cellular processes (13, 14, 23, 24) to interactions at the network level (9, 25). However, because of the multitude of nonlinear processes that govern neuronal activity, scaling cellular dynamics up to the level of macroscopic observations is not trivial (26). For this reason, population models (27, 28) are extremely useful for the analysis of both meso- and macroscopic epileptiform network activity patterns (9, 29, 30).

Here, we quantify and model the relationship between the ictal wavefront, the local LLFP, and the macroscopic electrocorticogram (ECoG). We examine the spatiotemporal relationship between spike trains and LLFP in simultaneous human microelectrode and ECoG recordings from spontaneous seizures. We show that the local wave of spike activity is correlated with both local and long-range effects. We present evidence that the latter effect includes a feedforward inhibitory response in the surrounding territory. Furthermore, we use our findings to model the interactions between the mesoscopic, propagating wavefront and the macroscopic, surrounding network, extending previous work (9). We attribute ongoing seizure activity to a dual scale-dependent role of feedforward inhibition and investigate the relationship between the dominant seizure frequency and the intrinsic connectivity parameters of the macroscopic model.

Results

Time Frequency and Spatiotemporal Analysis.

A movie published in ref. 2 shows that spiking at the wavefront and the LLFP appear to act on two timescales (Movie S1). A snapshot from this movie (Fig. S1) shows localized spike activity organized in a propagating wavefront (Fig. S1, Left) and LLFP activity as a more global distribution (Fig. S1, Right). The wavefront propagates at a speed of <1 mm/s (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S2), while the individual epileptiform discharges of the LLFP possess a more macroscopic organization and propagate at a much faster speed (0.26 m/s) (1). Despite these differences, we found that the global response is frequently delineated by the location of the wavefront, revealing a direct spatiotemporal relationship between the wavefront and oscillatory LLFP signal (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S3). From these observations, we were motivated to quantify this relationship.

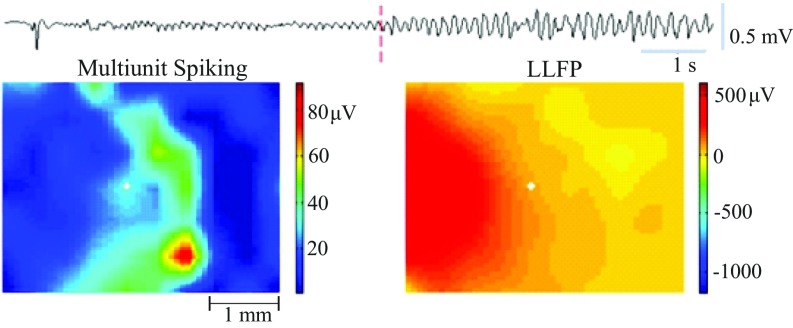

Fig. S1.

Example snapshot from a movie of a seizure from patient 2 from ref. 2. (Upper) LLFP recording from channel 15 (position indicated by the white dot in Lower) showing the seizure onset. Time point of Lower is noted with a red dotted vertical line. (Lower) Spatial representation of the (10 × 10) MEA. The 96 channels in the grid have been linearly interpolated using 56 channels with artifact-free recordings. (Left) Multiunit activity with the corresponding LLFP (2–50 Hz) signal in Right.

Fig. S2.

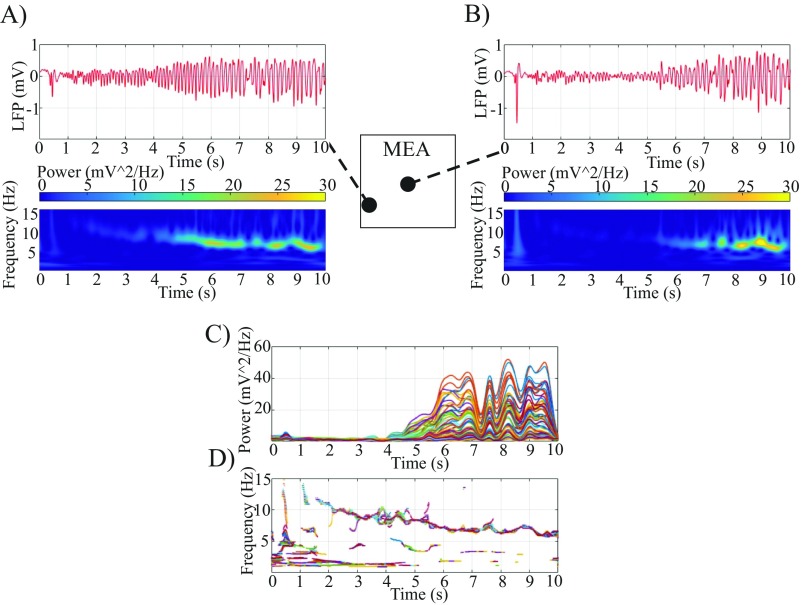

Wavelet decomposition of the LFP around seizure onset shows the evolution of a dominant frequency decrease from 10–11 to 5–6 Hz over time (for example, seizure from patient 1, seizure 1). (A) Microelectrode channel 22. Upper shows raw microelectrode signal; Lower shows the time frequency plot. (B) The same as in A for channel 50. (C) Power over time for all microelectrodes. Note the large increase in power associated with the drop in dominant frequency. (D) Dominant frequencies plotted for all microelectrodes.

Fig. S3.

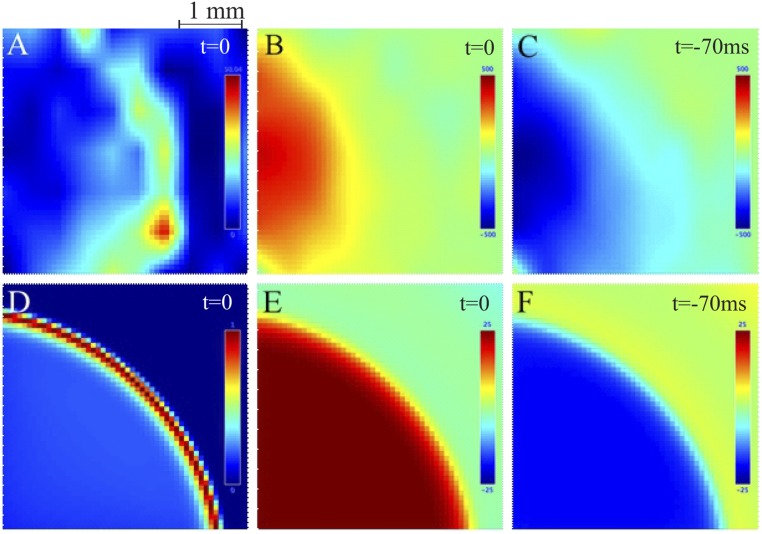

Spatial correlation of spiking and LLFP for the MEA (A–C) and simulation (D–F) shows similar patterns of activation. (A) A time snapshot, as in Fig. S1, shows the multiunit activity of the wavefront as it crosses the MEA. Color bar denotes amount of multiunit activity. (B) The corresponding LLFP at this time point shows a peak of a positive deflection in the area that the wavefront has already passed. Color bar represents the amplitude (microvolts) of the LLFP: in this case, only the positive amplitudes. (C) Approximately 70 ms earlier or two frames prior with a resolution of ∼35 ms per frame, which corresponds to one-half a period for the dominant seizure frequency in the theta band within the resolution of this analysis. Note that the LLFP shows strong amplitudes that correspond with the trough of the preceding negative deflection. Color bar is representative of LLFP amplitude. D–F portray the same results as in A–C for our simulated wavefront and LFP.

Spike-Triggered Averages.

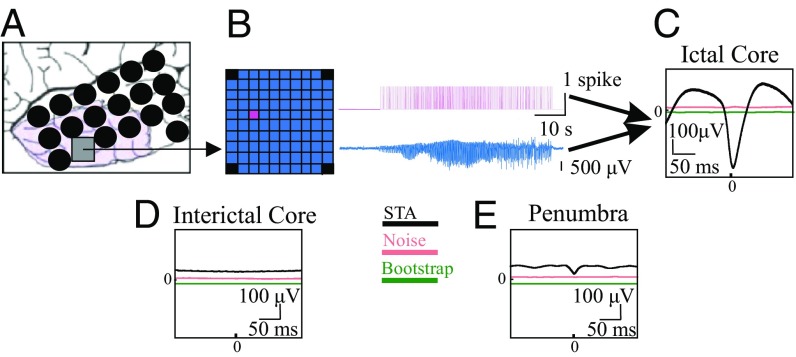

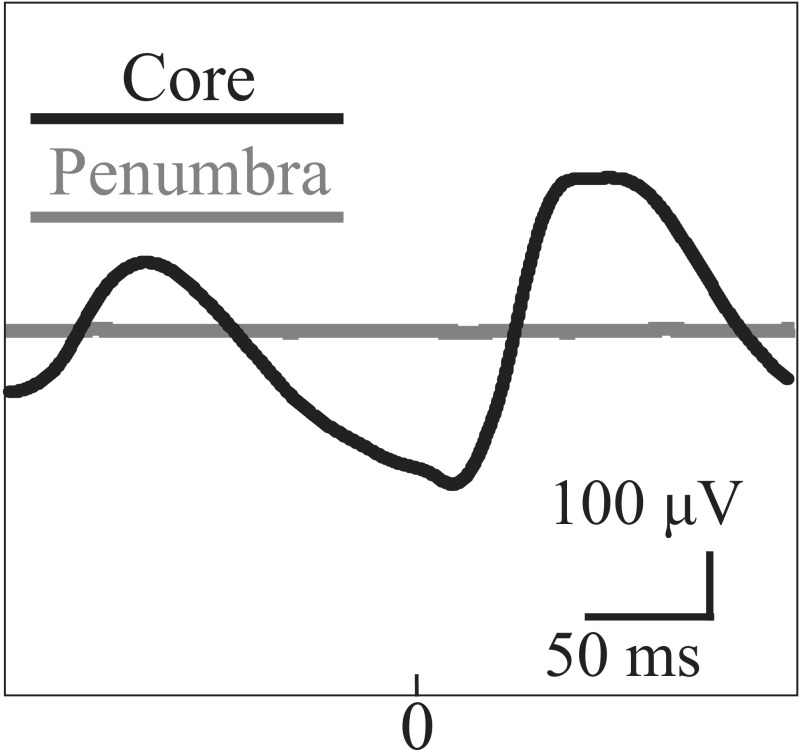

We wished to quantify the spatial range of the wavefront’s effect on the LLFP in the cross-scale relationship throughout the duration of the seizure. To accomplish this, we investigated the time-locked relationship between the spiking in the core and macroscopic LLFP activity via spike-triggered averages [STAs; i.e., the cross-correlation between the mesoscopic spike activity and the average LLFP across the MEA (termed pseudo-ECoG)]. Noticing that spiking from the entire seizure was comparable with spiking during the postrecruitment period (1) (Fig. S4), we used spike activity in the core from across the array. STAs have been previously used to examine the spatiotemporal relationship of LFPs across MEAs under task-related conditions (31), and our goal was to extend this method to include long-range correlations associated with macroscopic networks observed by ECoG during seizures. In Fig. 1, we show an example of the local, spike time-locked component of the pseudo-ECoG. The time-locked pseudo-ECoG signal can be clearly distinguished from the noise estimates, which were obtained both with plus–minus averaging that removes consistent signal components to estimate residual noise and with bootstrapping procedures that randomize our sample times (Materials and Methods and Fig. 1C) (bootstrapped difference: P < 0.0001, two patients, four seizures). Importantly, this strong time-locked component of the STA was not detected interictally or with penumbral spikes, confirming that only spiking associated with the core and propagating wavefront was correlated with the macroscopic LFP (Fig. 1 D and E). These results were consistent across patients (Fig. S5).

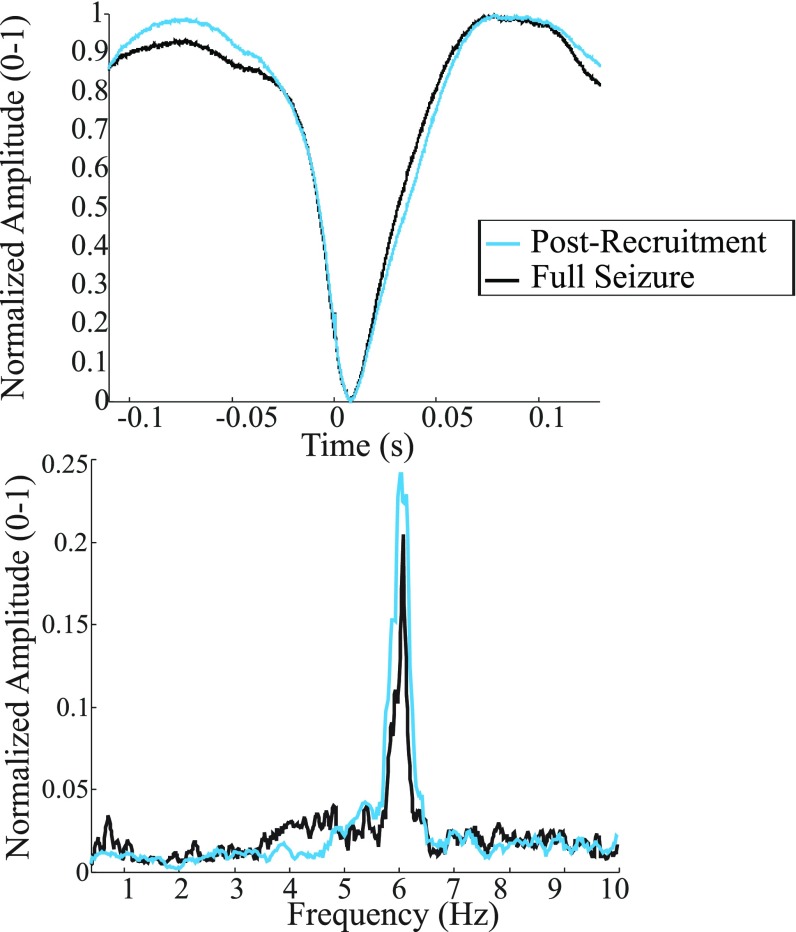

Fig. S4.

(Upper) Pseudo-ECoG STA using the entire seizure (black) or postrecruitment interval (cyan). (Lower) Amplitude spectra for the pseudo-ECoG in both epochs. Lower shows the similarity between spectra.

Fig. 1.

Spikes in the ictal core show a strong correlation with the LFP. (A) Example schematic of the MEA (gray square) and ECoG grid (black circles) placement for patient 1. Purple area denotes tissue that was later resected. (B) Cartoon MEA. Spike raster from a microelectrode is shown in magenta. Pseudo-ECoG signal (averaged LFP across the MEA) is shown in blue. (C) Example STA from spiking in the ictal core (black) with the noise estimates: with or without average (pink) and bootstrapped average (green). STAs and bootstraps were found to be significantly different (P < 0.0001) for all seizures recorded in the core (two patients, four seizures). (D) Example STA from interictal spike times. (E) Example STA from penumbral spike train (patient 4). Note that the noise estimate and bootstrap in C–E are slightly shifted from their zero mean to make them visible.

Fig. S5.

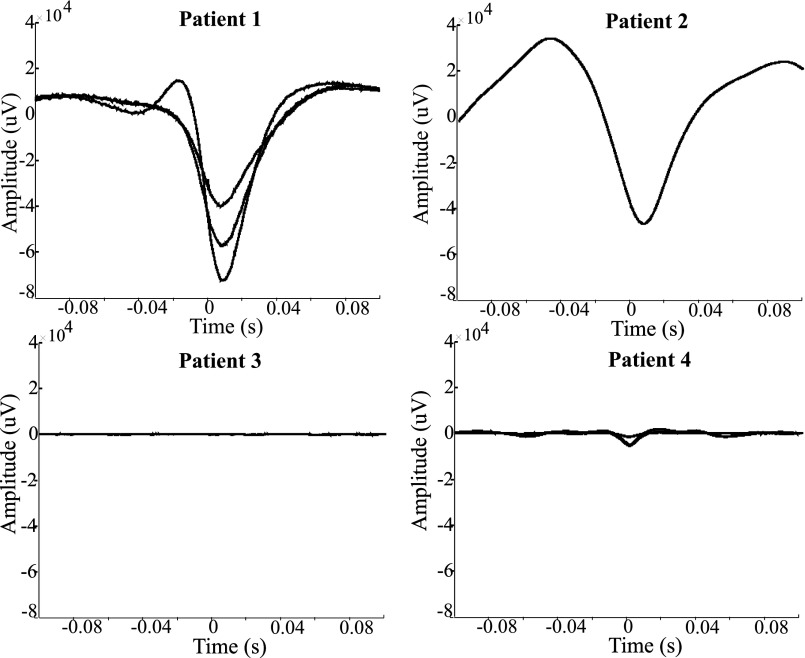

The pseudo-ECoG STAs for all seizures. Patients 1 and 2 had MEAs placed in the core and show large-amplitude STAs, including oscillations at the dominant seizure frequency in the theta band (5–8 Hz). In contrast, penumbra patients (3, 4) show low-amplitude STAs without strong oscillatory components.

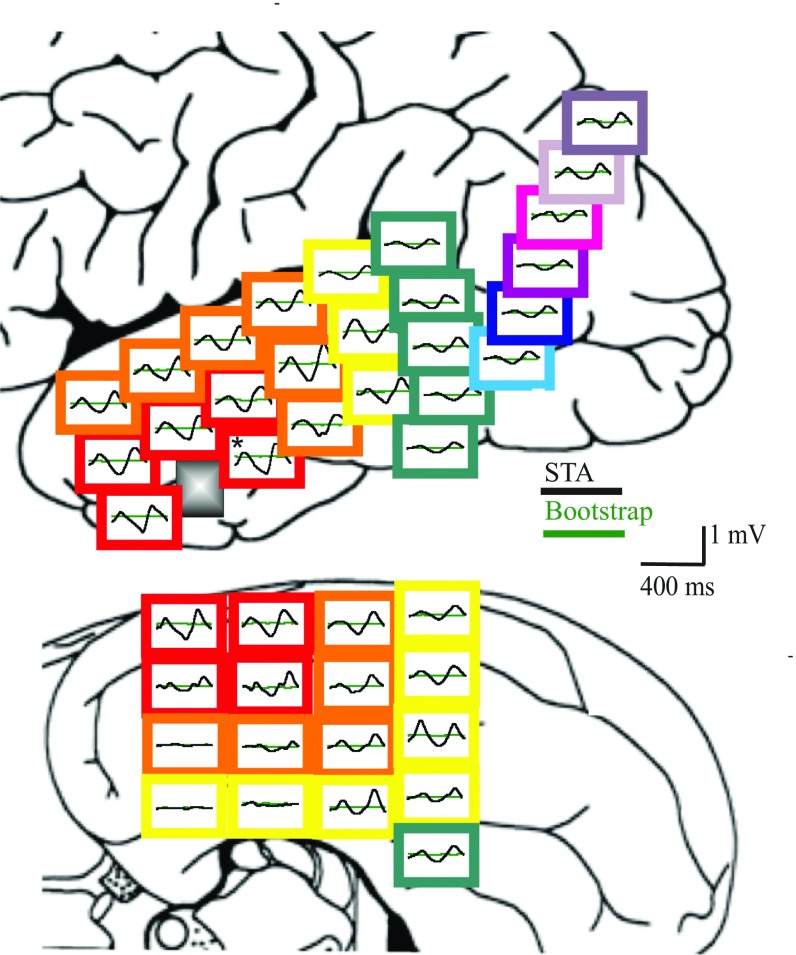

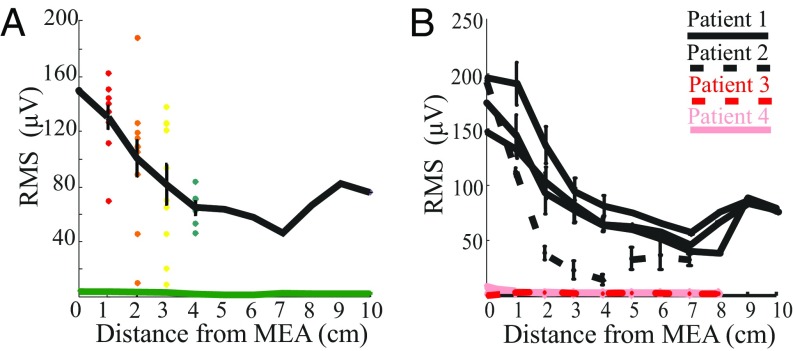

Subsequently, we analyzed the time-locked component between spikes from the core and macroscopic brain activity in the surrounding regions from the ECoG recordings. Fig. 2 depicts one set of example STAs and associated bootstrapped noise estimates across cortex. While the STAs from the core spike trains did show a distance-dependent decrease in amplitude, described by the rms values, over the first four centimeters (P < 0.01, two patients, four seizures), we observed that a significant component of the ECoG signal, well above the levels associated with the bootstrapped signals, remained correlated with the spike train at distances up to 10 cm (Figs. 2 and 3A) (P < 0.0001, two patients, four seizures). Contrarily, penumbral spike trains showed no such synchronization between spikes and ECoG signals (Fig. S6). These results were consistent across patients: only spiking from the core showed strong and statistically significant long-range correlations (Fig. 3B) (four patients, eight seizures).

Fig. 2.

Example of STAs from the core (patient 1) with long-range correlations between the spike train and ECoG. Each panel depicts the STA (black) from the ECoG electrode at that position and a bootstrapped noise estimate (green). Colored borders reference geodesic distance from MEA. Upper shows the lateral view; Lower is the corresponding basal view. *Electrode used for the core STA in Fig. S6.

Fig. 3.

Core shows strong long-range correlations. (A) rms Values of the example STAs in Fig. 2 are plotted vs. their distance from the MEA. Each point refers to an rms value from a single ECoG electrode. Colors of the points correspond with approximate distances from the MEA shown in Fig. 2. Zero distance refers to the STA at the MEA (pseudo-ECoG STA). The black trace connects the mean and SEM for patient 1’s STAs; the green trace shows mean and SEM of the bootstrapped noise estimates. STAs and bootstraps were significantly different (P < 0.0001) for all seizures recorded in the core. The rms values for the first 4 cm also show a strong distance-dependent drop off in amplitude (r = −0.53, P < 0.01 for seizure 1, patient 1). (B) Mean and SEM rms are consistent across patients: the black traces are from the ictal core (patients 1 and 2), and the red/pink traces are from the penumbra (patients 3 and 4).

Fig. S6.

Comparison of example STAs from ECoG signals created from spiking in the core (black) and from spiking in the penumbra (gray).

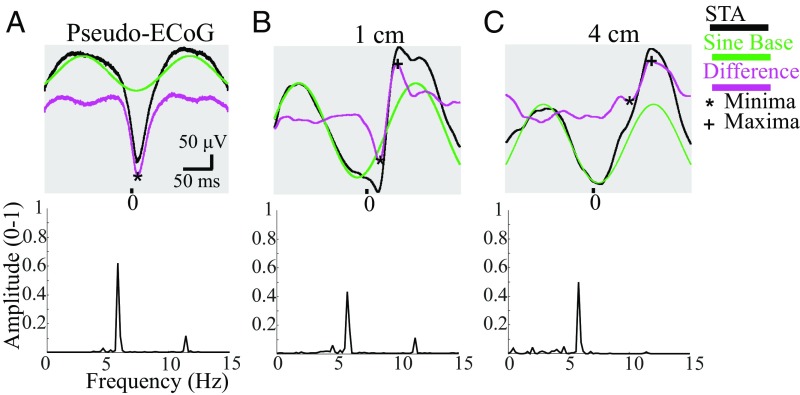

Decomposition of the STAs.

STA signals obtained between the core and ECoG could be decomposed into two parts: an oscillatory and nonoscillatory component (Fig. 4). The presence of the oscillatory component over a centimeter range extends previous findings that spiking in the core is phase-locked to the local LFP oscillation (1, 2, 4). The frequency of this oscillatory component is the same as the principal frequency of the ongoing ECoG seizure activity, ∼6 Hz (Figs. S2, S4, and S7), and is consistent across distances, as noted by the distinct peak in the amplitude spectra of the STAs (Fig. 4, Lower). Occasionally, a small-amplitude harmonic component was observed at 12 Hz (Fig. 4, Lower), but given the minimal effect of the harmonics, we fit the same sinusoidal base to all STAs from the same seizure. Since the oscillations in the STAs were consistently observed across distance and the MEA’s LLFP and ECoG signals showed power in the same frequency range (Fig. 4 and Figs. S4 and S7), we interpreted our findings as follows. The (constant) oscillatory component of the STA (green traces in Fig. 4) represents a global effect that can be associated with periodic motion in the cortical dynamical system. Likewise, the remainders of the STAs (magenta traces in Fig. 4) represent the local effects of the wavefront.

Fig. 4.

STAs are composed of a sinusoidal base and a remainder term. (A) Example pseudo-ECoG STA shows wavefront spiking effects that can be observed as the difference (magenta) between the STA (black) and a sinusoidal base (green). Lower represents the amplitude spectrum of the STA. *Local minimum, which we interpret as representing excitatory activity (SI Materials and Methods). (B) Example as in A from an ECoG electrode 1 cm from the MEA. Cross denotes local maximum, which we interpret as local inhibitory activity. (C) Example as in A from an ECoG electrode at a distance of 4 cm.

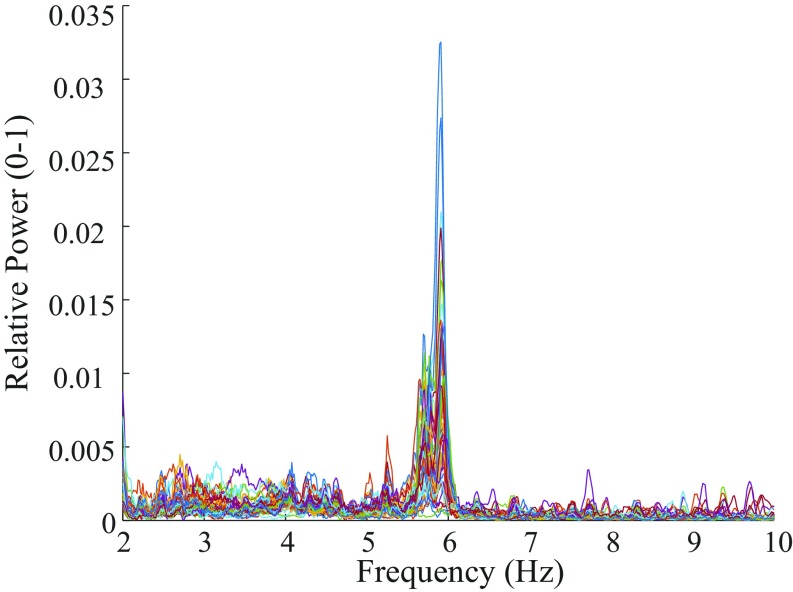

Fig. S7.

Normalized power spectra for all ECoG electrodes implanted in patient 1 during seizure 1. Note that all channels show a large spike in power around 6 Hz, the identified dominant seizure frequency and the dominant frequency observed on the corresponding STAs.

As outlined in SI Materials and Methods, negative and positive deflections in the extracellular potential can be interpreted as the combined effects of excitatory or inhibitory network activity, respectively. This interpretation hinges on the assumptions (i) that, during seizure activity, neuronal activity occurs across all neocortical layers; (ii) that the remotely located reference electrode does not significantly contribute to the recorded activity (i.e., the reference signal is close to zero); and (iii) that neuronal currents contribute to the measured signals via volume conduction. Accordingly, we interpreted the STAs as follows: at the MEA, the local spike contribution is represented by a downward deflection that correlates with a strong excitatory response, a result that corresponds well with previous evidence of failed inhibition at the core (Fig. 4, black asterisks) (2). In contrast, remote from the MEA, a positive peak is present and associated with intact local inhibition (Fig. 4 B and C, black crosses). At 1 cm away, the corresponding waveform is biphasic (Fig. 4B), and at 4 cm away, a clear positive component dominates (Fig. 4C).

Multiscale Model.

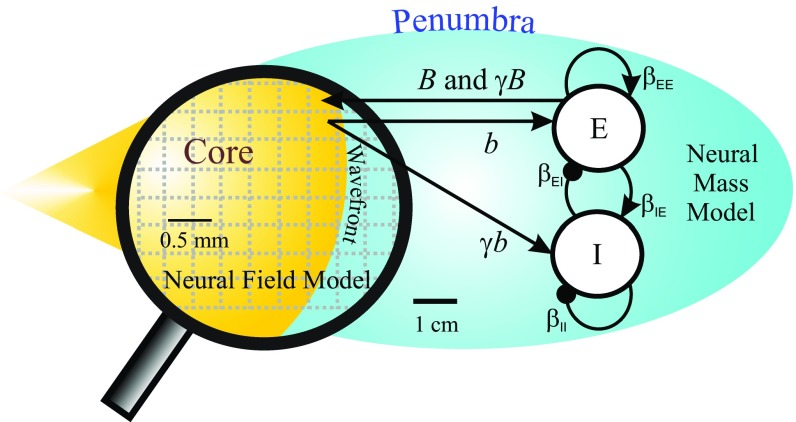

Using the scale differences of the spike wavefront and LFP activity (Fig. S1 and Movie S1) and the two components of the STA (Fig. 4), we were motivated to create a two-scale model to study the coupling across scales. At the mesoscale, we used a neural field to model the propagating spike wavefront. At the macroscale, we used a single neural mass model to represent the global activity from macroscopic cortical networks observed by ECoG (Fig. 5 and SI Materials and Methods). In the neural mass model, we removed the spatial information, because the frequency of the STA’s oscillatory component was constant across distance (Fig. 4, Lower). Our neural field model extended the 1D wavefront model previously described by ref. 9 that includes a Gaussian activation function to describe failure of inhibition caused by paroxysmal depolarizations. The output of this wavefront connects to the macroscopic network model to contribute to the overall seizure activity. In response, the output of the macroscopic network feeds into its environment, which includes feedback to the propagating spike wavefront. To confirm our model’s validity, we compared our simulation with the activity from the MEA. Similar to the recorded dataset, the dominant frequency decreases as the seizure develops, and there was a distinct spatial organization correlating the LLFP with the wavefront (Fig. S3 D–F).

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the multiscale model (reinterpreted from figure 1B in ref. 4). The model consists of a mesoscopic neural field model for the propagating wavefront that is connected to a neural mass model representing the surrounding macroscopic network. Mutual excitatory effects between the wavefront and neural mass model are represented by b and B, respectively. The activation of the inhibitory populations’ response, feedforward inhibition, is governed by Additional details on the parameters can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

The Role of Feedforward Inhibition.

While previous work (2, 7–9) has focused on the effects of failed local feedforward inhibition at the core, the positive deflections in our ECoG STAs suggest that feedforward inhibition is functional in the macroscopic surrounding territory (Fig. 4). Thus, we were interested in investigating the network dynamics associated with various levels of inhibition at the macroscale. In our model, we define the level of this functional, surrounding feedforward inhibition as the quotient (γ) between the external inputs from the propagating wavefront (b) of the continuous neural field that projects onto the inhibitory and excitatory populations of the macroscopic neural mass (Fig. 5). To determine the role of this feedforward inhibition on the seizure dynamics, we applied bifurcation analysis, which allows us to quantify how the dynamics of the system will respond as parameters change. Here, we quantified how the dynamic equilibria of the synaptic activity, uE, depend on the input from the wavefront, b, and on different levels of feedforward inhibition (γ) (Fig. 6). By investigating the dynamical changes associated with the wavefront input and feedforward inhibition (Fig. S8), we identified three distinct dynamical activity patterns that corresponded with varying levels of inhibition (an example of each is shown in Fig. 6): one scenario produces excessive oscillatory activity (Fig. 6A), one does not include seizure-like behavior (Fig. 6C), and one includes distinct pathways for seizure onset and termination (Fig. 6B).

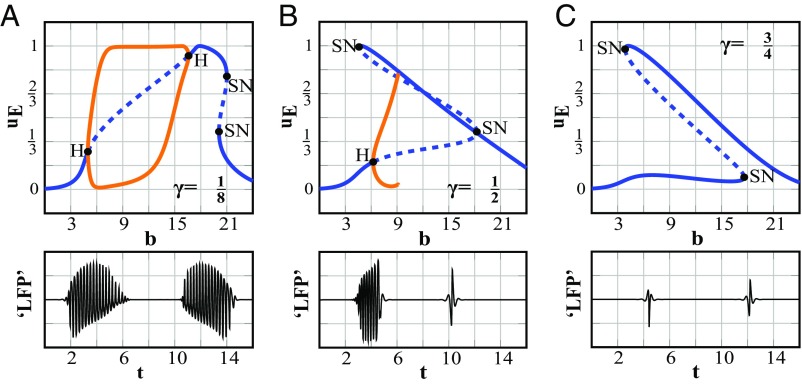

Fig. 6.

Bifurcation analysis evaluates the role of feedforward inhibition activated by the wavefront at the macroscale. Upper shows the input (b)-dependent dynamics for the macroscopic activity uE as bifurcation plots. Lower shows corresponding LFP signals generated when the input b is increased and then decreased. LFP signals were filtered with conventional EEG filters. (A) For , the stationary state undergoes a Hopf bifurcation (H), described by a periodic orbit (orange traces), for increasing input b. When the input is increased further, the ictal state is replaced by a strong depolarized state and SN bifurcation. When the input decreases, the same trajectory is passed through but in reversed order as seen by the two sets of oscillations in the LFP signal of Lower. (B) For , uE undergoes a Hopf bifurcation into the ictal state, and the ictal state is replaced by a strong activated state via a homoclinic bifurcation for increasing values of the input. When the input decreases, the strong activated state falls back to the initial rest state via an SN bifurcation. The LFP shows the distinct paths from seizure onset and offset in Lower. Note that input b is varied to produce the dynamics, and therefore, the interval between simulated seizure onset and offset is arbitrary. (C) When , only transients are present in the simulated trace.

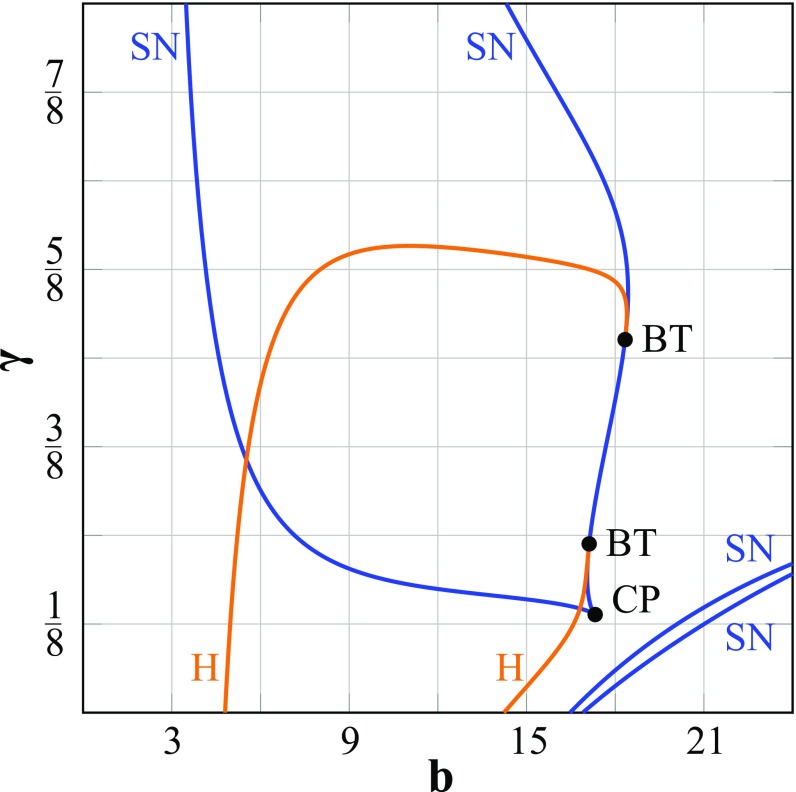

Fig. S8.

A two-parameter analysis shows how the bifurcation scenario of the macroscopic network depends on the degree of feedforward inhibition γ. The overall network input is determined by b. Note that the diagrams in Fig. 6 show the bifurcation analysis for the activity levels as a function of b and for γ = , , and . BT, Bogdanov–Takens bifurcation; CP, cusp point; H, Hopf bifurcation.

Fig. 6, Upper displays bifurcation diagrams (32) for three specific levels of feedforward inhibition (γ = 1/8, 1/2, and 3/4), representing state changes in synaptic activity, uE, when the input, b, is varied. Points on the solid blue curves in Fig. 6 indicate that a state change exists at the corresponding value of b. At the Hopf bifurcation points (H), the equilibrium loses stability, and a periodic orbit emerges (orange traces in Fig. 6), which can be observed as oscillations in the LFP. Here, the periodic orbit is stable (a so-called supercritical Hopf bifurcation) (32), and we can follow it as b is varied (Movies S2–S4). Fig. 6, Lower shows the EEG band-filtered signals associated with the trajectories that mimic seizure onset and offset.

For low levels of feedforward inhibition (e.g., γ = 1/8), the steady state undergoes a supercritical Hopf bifurcation at b = 5.0 that terminates at another Hopf bifurcation point at b = 16.6 (Fig. 6A). Therefore, for 5.0 < b < 16.6, stable periodic solutions exist that model synchronized ictal behavior as oscillatory activity (Fig. 6A, Lower and Movie S2). Comparatively, for moderate values of feedforward inhibition (e.g., γ = 1/2), the behavior is qualitatively the same for small values of b (Fig. 6B), with the fixed point losing its stability and switching to periodic behavior at b = 6.2, and for larger values of b, with a stable fixed point that represents strong activation. However, in contrast to the former case, the periodic solutions now terminate at a homoclinic bifurcation point at b = 9.1, where the periodic orbit collides with an equilibrium and the period goes to infinity (32) (Movie S3). Finally, for high values of feedforward inhibition (e.g., γ = 3/4), there are no periodic solutions (Fig. 6C), but the model does show saddle-node (SN) points, in which two equilibria merge and disappear (Movie S4).

We then mimicked the effect of the ictal wavefront (i.e., input b) by determining a trajectory across the diagrams in Fig. 6. Note that, if b first increases and then decreases, the systems’ dynamics critically depend on γ. In the first scenario (γ = 1/8), the system must enter and exit the oscillatory state via the same path (i.e., the simulated LFP shows oscillatory activity with both increasing and decreasing b) (Fig. 6A, Lower and Movie S2). However, in the second scenario (γ = 1/2), the system enters the oscillatory state as b increases but returns to its initial state via a second distinct path with an SN bifurcation (Fig. 6B and Movie S3), which agrees well with the clinically observed differences for seizure onset and offset.

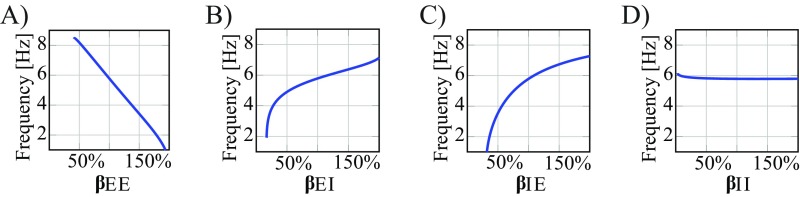

Because of the global nature of the seizure’s oscillatory component, our model can also be used to determine how the macroscopic network’s connectivity parameters affect the frequency of the seizure dynamics (Fig. S9). While the wavefront propagates across the neural field and activates the macroscopic neural mass, the surrounding network’s feedback to the system influences the frequency of the oscillatory discharges. This influence on the spectral seizure dynamics can be attributed in part to the connectivity associated with the neural mass. Just as previous work has suggested that network size and connectivity can impact the resonance frequencies of a network (33), we found that stronger excitatory–excitatory connections could lead to a decrease in the dominant seizure frequency (Fig. S9A), while stronger excitatory–inhibitory and inhibitory–excitatory connectivity could increase the dominant frequency (Fig. S9 B and C). Furthermore, the change in frequency at the MEA can be described by the nonlinear dynamics associated with intact inhibition in the macroscale model and the corresponding homoclinic bifurcation.

Fig. S9.

Dominant frequency at seizure onset is affected by the connectivity parameters at the macroscale as a function of (A) excitatory–excitatory connections, (B) excitatory–inhibitory connections, (C) inhibitory–excitatory connections, and (D) inhibitory–inhibitory connections.

SI Materials and Methods

Patients.

Study participants (Table S1) at Columbia University Medical Center consisted of consented patients with pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy who underwent chronic intracranial EEG studies to help identify the epileptogenic zone for subsequent removal. Procedures were approved by the internal review board committees at Columbia University Medical Center and The University of Chicago, Comer Children’s Hospital. The patients’ surgeries and treatment plans were not directed by or altered as a result of these studies.

Table S1.

Patient demographics

| Patient (age/gender) | ||||

| Patient features | Patient 1 (32 y old/female) | Patient 2 (19 y old/female) | Patient 3 (30 y old/male) | Patient 4 (39 y old/male) |

| Implant location | Left lateral and subtemporal | Right lateral and subtemporal, parietal, occipital | Left lateral frontal, mesial frontal, temporal | Left lateral and mesial frontal |

| MEA location | Left inferior temporal gyrus 2.5 cm from anterior temporal pole | Right posterior temporal, 1 cm inferior to angular gyrus | Left supplementary motor area, 3 cm superior to Broca’s area | Left lateral frontal 2 cm superior to Broca's area |

| Seizure onset zone | Left basal/anterior temporal (including MEA site) | Right posterior lateral temporal, (including MEA site) | Left supplementary motor area (including MEA site) | Left frontal operculum (3 × 3-cm cortical area, including MEA site) |

| Days recorded | 5 | 28 | 4 | 4 |

| No. of seizures analyzed | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Seizure type(s) | Complex partial | Complex partial with secondary generalization | Complex partial/tonic | Complex partial |

| Pathology | Mild CA1 neuronal loss; lateral temporal nonspecific | Nonspecific | N/A (multiple subpial transections performed) | Nonspecific |

N/A, not applicable.

A 96-channel, 4 × 4-mm MEA (Utah array; Blackrock Microsystems) was implanted along with subdural electrodes (ECoG) with the goal of recording from seizure onset sites. Additional details of study enrollment and surgical procedures are described in ref. 2. Signals from the MEA were acquired continuously at a sample rate of 30 kHz per channel (0.3-Hz to 7.5-kHz bandpass, 16-bit precision, range ± 8 mV). The reference was epidural. The ECoG was acquired using a standard clinical video EEG system (XLTek; Natus Medical Inc.) at a sample rate of 500–2,000 Hz per channel (0.5-Hz high pass, low pass set to 0.25 times the sampling rate, 24-bit precision). ECoG and MEA recordings were time-locked using a pulse-coded signal delivered to digital inputs of both recording systems. Up to three seizures from each patient were selected for detailed analysis to avoid biasing the dataset from the patients from whom many seizures were recorded. Seizure recordings were categorized as core—seizure-generating area—or penumbra—surrounding unrecruited territory—using methods described in ref. 2. Channels and time periods with excessive artifact or low signal-to-noise ratio were excluded.

Wavelet Analysis and Image Decomposition.

Separate images were produced for the spike signal (300 Hz to 3 kHz) and the LLFP (2–50 Hz) of the broadband MEA recordings. Image decomposition was performed using

This procedure was applied to decompose the spatial component of the positive and negative deflections for both the recorded seizure oscillations and the simulated seizures. Time frequency plots of the seizure activity were obtained using an analytical Morlet wavelet.

We found that the amplitude of the LLFP is increased in the recruited territory (Fig. S3 A–C). By analyzing the polarity of the LLFP at the MEA, we also noted that the LLFP activity in the recruited core corresponds with oscillations in the theta band (5–8 Hz), with the positive peak of the LLFP preceded by a negative trough ∼70 ms, or two frames prior with a resolution of ∼35 ms per frame, which corresponds to one-half a period for the dominant seizure frequency in the theta band within the resolution of this analysis (Fig. S3). We confirmed previous results regarding the time frequency behavior of the microelectrode signals by applying a continuous wavelet transform based on an analytical Morlet wavelet, which has not previously been used to analyze these data, to each raw microelectrode signal without artifacts (Fig. S2). We observed that the wavefront could be identified by a clear change in the intensities associated with a speed of <1 mm/s [for example, 0.92 ± 0.12 mm/s propagation speed for patient 1, seizure 1 (see below)] and that this intensity/power increase corresponded with a decrease in dominant seizure frequency, plateauing between 5 and 6 Hz across all microelectrodes (Fig. S3 C and D). Thus, we noted that the dominant frequency oscillations of the LLFP were strongly correlated with the spiking at the recruited core.

Computing the Speed of the Wavefront.

If we let denote the time at which the wavefront reaches position , the velocity vector is given by

where and denote the partial derivatives of T with respect to and , respectively. It follows that the speed of the wave at position is given by

Applying a continuous wavelet transform based on an analytical Morlet wavelet to each raw microelectrode signal without artifacts, the propagating wavefront could be identified by a clear change in the power of the dominant frequency (Fig. S2). This motivated us to estimate the arrival time of the wavefront at a certain microelectrode by thresholding the normalized power at that electrode. In other words, for each artifact-free microelectrode, we first computed the maximal power of the wavelet-transformed signal and then estimated the value of T at the electrode’s position by identifying the first time at which a certain fraction of the maximal power was reached. Using θ = 0.4 and an interelectrode distance of 0.4 mm, we could estimate the partial derivatives and for the inner 8 × 8 electrodes.

, where i corresponded to the row and j corresponded to the column of the microelectrode; Ti,j was the corresponding estimated arrival time. Finally, the propagation speeds at the inner 8 × 8 electrode locations were estimated by

Signal Processing.

We consider the multiunit spike train s(t) of the MEA, either from the core or the penumbra, composed of spiking from all microelectrodes without artifact:

Given a spike train of spikes from the duration of the seizure, the STA [i.e., the cross-correlation (42) between spike train and the ECoG] is defined as

We calculate the STA for two types of LFPs: (i) pseudo-ECoG activity determined by averaging activity across the MEA and (ii) recordings from the ECoG.

Model.

Our model includes two components: macroscopic and mesoscopic elements. The macroscopic model is a neural mass, and the mesoscopic component is a neural field, including an explicit spatial component. The two model components are coupled via their excitatory connections that provide both feedforward excitation and feedforward inhibition via the local inhibitory cells.

Modeling the macroscale.

This Wilson–Cowan type model (27) consists of an excitatory (E) and an inhibitory (I) population, with (presynaptic) activities uk that evolve according to

Here, 1/αE = 1/125 s and 1/αI = 1/25 s are synaptic time constants representing excitatory and inhibitory transmission, respectively. The total input current jk to population k is given by

where the parameter denotes the connection strength from population to population , with = 10, = −14, = 12, and = −5, and is external input. We will assume that

where [0,1]. In other words, the inhibitory population receives a fraction of the external input to the excitatory population. After we couple the macroscopic model to a mesoscopic model, represents input from the excitatory population of the latter, and sets the level of feedforward inhibition (Fig. 6). Lastly, the spiking rate function converts synaptic input to population into its average spiking rate. As in ref. 9, the conversions into spiking rate are represented by Gaussian functions, modeling depolarization block for high inputs:

Parameter values are given by , , , , and .

Modeling the seizure wavefront (mesoscale).

For the mesoscopic formalism, we extend our macroscopic model with a spatial variable. The spatial domain was discretized into 90 × 90 points. However, to reduce (visible) boundary effects, only the center 50 × 50 points are shown. We denote corresponding quantities U and J (capital), writing

Postsynaptic input is now given by an integral over the spatial domain and takes the form

Here, is the connection strength from neurons of population at position to neurons of population at position and is given by

where , , , , , , .

Interaction between the macro- and mesoscale.

When the macro- and mesoscopic models are coupled, external input to the macroscopic network is given by the average activity of the excitatory population of the mesoscopic wavefront described by

where the constant background input sets the model close to seizure onset.

Similarly, every point in the wavefront receives external input that is proportional to the activity of the excitatory population in the macroscopic network,

where and denote the connection strength from the macroscopic network (neural mass M) in the penumbra to the wavefront surrounding the core (neural field F) and vice versa, respectively (Fig. 5).

Synthetic LFP signals.

In the macroscopic model, the raw LFP signal is modeled using the activity of the excitatory population (which is proportional to the total synaptic current generated by this population):

The LFP traces in Fig. 6 are then obtained by filtering the raw signal with a typical EEG bandpass of 1–70 Hz.

In the mesoscopic model, the raw LFP is modeled by the total synaptic current generated by excitatory population:

This signal is filtered with a 2- to 50-Hz bandpass filter, such that it can be compared with experimentally obtained LLFP signals (Fig. S3).

Rationale of the ECoG and pseudo-ECoG polarity interpretation.

Previous papers based on these data (1, 2) provided evidence that ongoing seizure propagation at the core and its surrounding results from a localized failure of inhibitory constraint. This local failure of inhibition was modeled, and its dynamics were analyzed in ref. 9, which showed that this is indeed a candidate mechanism. In this work, we further argue that preserved long-range inhibition is required to produce distinct dynamical paths for seizure onset and offset (Fig. 6B).

Accordingly, our interpretation of the STA signal (Fig. 4) is

-

i)

that local excitation and failed inhibition at the core are associated with net depolarization of the network, reflected in the negative deflections of the STA, and

-

ii)

that long-range excitation with preserved inhibition at centimeter distance from the core is associated with both negative and positive deflections in the STA waveforms, respectively.

We motivate this interpretation as follows. In general, inference of source properties from extracellularly recorded signals is an ill-posed inverse problem, and additional constraints, preferably based on the underlying biophysics, are needed. We included the following assumptions and considerations.

-

i)

Because of the remote position of the reference electrode (extracranial for the MEA recordings and on an inverted grid for the ECoG measurements), the reference signal does not significantly contribute to the recorded activity. Thus, we consider the reference signal close to zero.

-

ii)

During seizures, neuronal activity occurs across all neocortical layers.

-

iii)

Neuronal currents [i.e., the sum of the depolarizing/inward currents (e.g., Na+, Ca2+ currents) and hyperpolarizing/outward currents (e.g., K+, Cl− currents)] contribute to the measurement via volume conduction.

In the following example, we apply these assumptions to analyze the effects of depolarizing currents on the voltage recording with the understanding that hyperpolarizing currents show the opposite effect.

Depolarizing currents and voltage recordings.

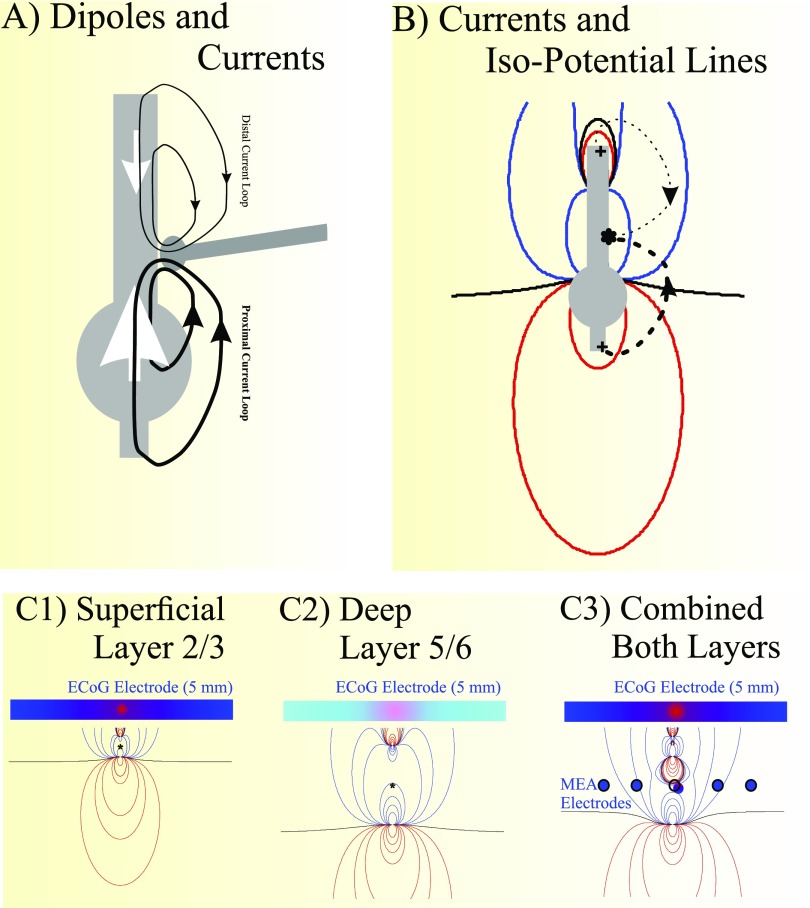

We start with the standard current dipole model (43) and extend a single current dipole model to include two current dipoles (Fig. S10 A and B). As seen in Fig. S10A, neuronal activation leads to current loops that flow both proximally, toward the soma and axon hillock, and distally, away from the soma. Note that the proximal component of the collective membrane currents is larger than the distal component in the opposite direction (Fig. S10A, white arrows). This results from the lower resistance toward the soma compared with the narrower, branching dendritic arbor toward the distal part of the cell. Most modelers consider the effect of the membrane currents as a single net vertical dipole. However, to accurately analyze the current and potential distributions around an active neuronal segment, we instead consider both dipoles: one dipole associated with the proximally oriented current loops and one with the distally oriented current loops (Fig. S10A).

Fig. S10.

(A) Cartoon of a neuron with excitatory synaptic activation showing current loops (black traces) moving to the distal and proximal ends of the neuron and the associated vertical current dipole representation (white arrows). (B) Where activation occurs and current enters the cell (asterisk), the synaptic activity gives rise to current loops (dashed lines), and a potential field is generated: positive isopotential lines (red), negative isopotential lines (blue), and zero isopotential lines (black). Where the current enters the cell, the extracellular potential is negative, and where it exits the cell (e.g., +), the potential is positive (or less negative). Current flows according to the potential gradient. C1 shows the isopotential lines of a superficially (layer 2/3) located neuron, C2 shows the isopotential lines for a deep (layer 5/6) cell, and C3 is the combined effect of both. Note that the top part of the field is truncated at the cortical surface where a 5-mm-sized ECoG electrode samples the average potential across its surface. Although the effects of deep sources are more attenuated than superficial effects, the size of the positive potentials at its surface is larger for the deep source compared with the superficial one. A number of MEA microelectrodes used to compute the pseudo-ECoG are shown in C3. The average potentials picked up by the ECoG electrodes are dominated by the negative part of the potential distribution, similar to what is recorded by the MEA electrodes.

By considering the current loops of both dipoles, we can better visualize the LFP, because current flows along the gradient of the LFP that surrounds the activated neuronal segment. In short, potential fields can be defined as the scaled average of the currents, in, weighted by the distance between source and electrode, rn (e.g., equation 12 in ref. 42), and a dipole’s potential field directly derives from that formalism. Thus, we can compare the current loops and the corresponding potential fields at the activated neuronal segment (Fig. S10B). In Fig. S10B, examples of proximal and distal current loops are indicated by the dashed lines, and the corresponding isopotentials around the neuron are indicated with solid lines. Fig. S10B shows that the extracellular potential is negative (Fig. S10B, blue solid lines) at the active depolarizing segment (indicated by the asterisk in Fig. S10B), but the potential is positive (or less negative) (Fig. S10B, red solid lines) at the locations where the membrane current is outward (two examples indicated by + in Fig. S10B).

If we now consider the LFP recorded by an ECoG electrode, we evaluate the potential fields from the depolarized segment at the cortical surface. Therefore, both the positive (Fig. S10C, red) and negative (Fig. S10C, blue) potential fields are sensed across the electrode, but the positive potential field is significantly smaller (Fig. S10C1, ECoG electrode). Since the ECoG electrode measures the average potential across the electrode area (5-mm diameter), the recorded signal is negative.

We can then ask how activity at different depths would affect this result. Fig. S10C shows the potential fields for a superficial source (Fig. S10C1), a deep source (Fig. S10C2) and the combined (superimposed) field of both sources (Fig. S10C3). Again, both the positive (Fig. S10C, red) and negative (Fig. S10C, blue) potentials are sensed across the ECoG electrode, but we see that the strength of the potentials from deeper sources (Fig. S10C2) show more attenuation because of distance between the electrode and the source (the lesser strength is represented by the lighter red and blue colors in Fig. S10C). Correspondingly, the width of the positive potential field increases with increased distance (as seen by the wider red portion of the ECoG electrode in Fig. S10C2).* When sources from different depths are combined (Fig. S10C3), the small positive components vanish, since the negative components from superficial sources are much less attenuated than the positive effects of the deep sources.

In contrast to the ECoG electrodes, microelectrodes from the MEA record the potential from much smaller areas of cortex. As shown in Fig. S10C3, most MEA electrodes measure the negative field components during depolarization. This finding agrees with our interpretation, since the negative spikes in individual microelectrodes are superimposed on slower negative waves, and the average of 96 MEA LLFPs (our pseudo-ECoG) correlates as well with neighboring ECoG electrode signals as other neighboring ECoG electrodes do.

Interpretation of our recordings.

We now can interpret negative potentials as current flowing away from the electrode, resulting from net depolarization/excitation of the underlying population of neurons, while current flowing toward the electrode is caused by net hyperpolarization/inhibition (44). When a recording includes both inhibition and excitation, the resulting measurement reflects the superposition of these activities (i.e., a representation of the net activity), where the voltage recorded represents the strongest component.

Discussion

We applied a combined data analysis and modeling approach to show how cortical activities at different spatial scales can interact and how these interactions affect the observed dynamics (Figs. 5 and 6). We find that, during a propagating seizure, the mesoscopic ictal wavefront and macroscopic network must interact to sustain the ictal state. The mesoscopic wavefront may function as a mathematical forcing term in the equations that govern the oscillatory seizure activity, while macroscopic connectivity properties have a strong impact on the dominant frequency of the seizure activity seen on ECoG recordings (Fig. S9).

Time frequency analysis allowed us to identify the passing of the ictal wavefront of spike activity at the mesoscale and determine the dominant frequency over the course of the seizure (Fig. S2). In conjunction with our modeling efforts, we were able to explore some of the contributing factors to the dominant seizure frequency. Previous work has identified the weakening of the ictal wavefront as one contributing factor to the dominant frequency (1). Our work presents evidence for additional factors, such as macroscopic connectivity. While the seizure is initially activated by the ictal wavefront that may weaken as the seizure develops, the macroscopic network influences the global oscillations and has a direct impact on the ictal wavefront’s progression (Figs. 4 and 6). Our findings suggest, therefore, that sustained seizure activity is critically dependent on a feedback loop between mesoscopic (the ictal wavefront) and macroscopic networks.

To show that the correlations between spike activity and LLFP may actually traverse scales under special circumstances, such as focal seizure activity, we extended the approach of ref. 31. Using STAs between micro- and macroelectrodes to experimentally probe the cross-scale relationship, we were able to correlate spikes from a small mesoscopic area of cortex with long-range macroscopic activity. Although the presence of long-range correlations across neural signals, including the ECoG, is well-known (3, 34, 35), we show that, during seizures, a significant component of this correlation can be related to the spike activity in the core (Figs. 2 and 3). Previous studies indicate that the core is contained within the large territory examined but occupies only a small percentage (<20%) of the area as defined by the presence of phase-locked high gamma activity on the electrodes (4). Despite its small size, core activity has previously shown some cross-scale effects. For example, mesoscopic failure of inhibition at the core is associated with neuronal paroxysmal depolarizations (9), high gamma activity corresponds with small network activity that crosses scales through volume conduction (36), and ictal discharges have been shown to be composed of traveling waves seeded from the ictal wavefront that spread both outward into the penumbra and backward into the ictal core (1). In addition, we show that the wavefront and subsequent spiking in the core are correlated to the seizure state, since neither the spikes during interictal periods nor penumbral spikes show a significant time-locked component to the global signals (Fig. 1 and Fig. S6).

We hypothesize that the wavefront initiates a global perturbation that is sustained by spikes in the core, as suggested by the excitatory deflections (marked as local minima in Fig. 4 B and C; SI Materials and Methods) in the STAs. Likewise, the ECoG STAs can be interpreted to include a consistent inhibitory response after excitation (local maxima in Fig. 4 B and C), corresponding with our hypothesis that feedforward inhibition is both activated in the surrounding territories and a critical determinant of seizure dynamics (Fig. 6B). Work presented by ref. 1 has also shown that the speed of the forward traveling waves was lower than the backward waves, suggesting higher inhibitory tone in the penumbra compared with the core. While other candidate mechanisms may be put forward, our interpretation is (i) consistent with previous analyses of these data (1, 2), (ii) agrees with past (9) and current modeling results (Fig. 6B), and (iii) is supported by biophysical arguments and our measurement configuration (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S10).

Because of our observations at the millimeter and centimeter scales, we constructed a simple, tractable model based on the neural population approach (27, 28). A critical aspect of our model is the inclusion of a Gaussian activation function that corresponds with depolarization block and can describe local failure of inhibition (9) and interaction between local and global networks (Fig. 5). In our model, γ defines the level of feedforward inhibition at the macroscale. As illustrated in Fig. 6B, γ = 1/2 is associated with two distinct dynamical pathways: one path that leads from preictal to ictal states and another that leads from ictal to postictal states, as is observed on clinical recordings of seizures as well. Such distinct pathways do not exist if feedforward inhibition fails at the macroscale (Fig. 6A) or is strong enough to prevent the network from oscillating (i.e., seizing) (Fig. 6C). Based on the distinct dynamics observed for seizure onset and offset, we find that our recordings are best represented by the scenario in Fig. 6B. Nonetheless, we note that spreading depolarizations, associated with saturation of neuronal activity, do exhibit symmetry at onset and offset similar to that observed in Fig. 6A (37). In short, our model allows for the potential study of other related physiological states beyond sustained seizure activity, such as spreading depolarizations mentioned above and spreading depression associated with ictogenesis (23).

Although our multiscale model can explain the ongoing seizure activity that we observe and presents dynamical pathways for seizure onset and offset, it cannot explain the cause of the transitions into and out of the seizure state. As in most modeling approaches, we mimic seizure onset by providing a strong input to a local network and stop the seizure by reducing the strength of the ictal wavefront to the macroscopic network (Fig. 6, Lower). Despite these limitations, our model describes how neuronal function at meso- and macroscales interacts to sustain the seizure. Clinically, these cross-scale interactions during seizure activity lead to a “chicken and egg” scenario, where both the mesoscopic and macroscopic networks interact to sustain the oscillatory activity. Thus, the model created here allows for exploration of perturbations that abolish this interaction. For example, given the strong cross-scale relationship, perturbations, such as electrical stimulation, applied anywhere within the recruited network may be enough to disrupt seizure activity. Ultimately, one might use our approach to evaluate methods of terminating ongoing seizure or to study the multiscale dynamics of seizures for different anticonvulsant strategies.

Materials and Methods

Patients.

Study participants (Table S1) at Columbia University Medical Center consisted of consented patients with pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy who underwent chronic ECoG studies to help identify the epileptogenic zone for subsequent removal. Procedures were approved by the internal review board committees at Columbia University Medical Center and The University of Chicago, Comer Children’s Hospital. Patients were implanted with a 96-channel, 4 × 4-mm MEA (Utah array; Blackrock Microsystems) along with subdural electrodes (ECoG). The Utah array recordings used a skull peg (pedestal) reference selected based on daily assessment of recording quality. The reference for ECoG recording was an epidural upside-down strip placed distant to the coverage area. Seizure recordings were categorized as core or penumbra using previously described methods (2) (SI Materials and Methods).

Signal Processing.

We consider the multiunit spike train of the MEA, from either the core or the penumbra, composed of spiking from all microelectrodes without artifact. We defined the STA as the cross-correlation between spike train and the ECoG (38). We calculate the STA for two types of LFPs: (i) pseudo-ECoG activity determined by averaging activity across the MEA and (ii) recordings from the ECoG (SI Materials and Methods).

Control STAs were obtained in two ways. In the first method, a ± average estimated residual noise by removing consistent signal components by inverting alternating trials before averaging (38–40). The second method used a bootstrapping procedure with random time stamps to create a distribution of 100 control STAs.

Amplitude was quantified by calculating the rms of the STAs. Distance was described geodesically using the distance of 1 cm between ECoG electrodes. Relative amplitude spectra are normalized by the sum of the amplitudes of the whole spectrum.

Statistics.

Distance-dependent drop off was quantified using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Difference between the bootstrapped data and ECoG was determined using a z test.

Model.

Our multiscale model consists of coupled mesoscopic and macroscopic components. Given the nature of the MEA data, which represent multiunit (population) activity, the macroscopic model is a neural mass, and the mesoscopic component is a neural field, including an explicit spatial component. The two model components are coupled via their excitatory connections that provide both feedforward excitation and feedforward inhibition (SI Materials and Methods).

Bifurcation Analysis.

All bifurcation diagrams for the model were created with MATCONT (41).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hil Meijer and Jack Cowan for valuable discussion and suggestions. T.L.E., C.A.S., and W.v.D. were supported by NIH Grants R01 NS095368 and R01 NS084142. W.v.D. was supported by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Travel Grant 040.11.506.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: Human data will be shared on request in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) law. All other code and data has been deposited on GitHub and can be accessed at https://github.com/kodi66/Cross-Scale-Effects.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Thus, when sensing the potential of a deep excitatory source with a relatively small surface electrode, one might measure a small positive potential. This positive component was also reported in ref. 43 (waveform amplitude in figure 5A in ref. 43). Note that, in this study, the electrode size is not included in the analysis.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1702490114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Smith EH, et al. The ictal wavefront is the spatiotemporal source of discharges during spontaneous human seizures. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11098. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schevon CA, et al. Evidence of an inhibitory restraint of seizure activity in humans. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1060. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer MA, Cash SS. Epilepsy as a disorder of cortical network organization. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:360–372. doi: 10.1177/1073858411422754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss SA, et al. Ictal high frequency oscillations distinguish two types of seizure territories in humans. Brain. 2013;136:3796–3808. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinet LE, et al. Human seizures couple across spatial scales through travelling wave dynamics. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14896. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truccolo W, et al. Single-neuron dynamics in human focal epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevelyan AJ, Sussillo D, Watson BO, Yuste R. Modular propagation of epileptiform activity: Evidence for an inhibitory veto in neocortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12447–12455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2787-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trevelyan AJ, Sussillo D, Yuste R. Feedforward inhibition contributes to the control of epileptiform propagation speed. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3383–3387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0145-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer HG, et al. Modeling focal epileptic activity in the Wilson-Cowan model with depolarization block. J Math Neurosci. 2015;5:7. doi: 10.1186/s13408-015-0019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Ramírez LR, Ahmed OJ, Cash SS, Wayne CE, Kramer MA. A biologically constrained, mathematical model of cortical wave propagation preceding seizure termination. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner FB, et al. Microscale spatiotemporal dynamics during neocortical propagation of human focal seizures. Neuroimage. 2015;122:114–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Gils S, van Drongelen W. Modeling epilepsy. In: Jaeger D, Jung R, editors. Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience. Springer; New York: 2015. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Drongelen W, et al. Emergent epileptiform activity in neural networks with weak excitatory synapses. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2005;13:236–241. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.847387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Drongelen W, et al. Role of persistent sodium current in bursting activity of mouse neocortical networks in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2564–2577. doi: 10.1152/jn.00446.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Drongelen W, Lee HC, Stevens RL, Hereld M. Propagation of seizure-like activity in a model of neocortex. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;24:182–188. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e318039b4de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lytton WW. Computer modelling of epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:626–637. doi: 10.1038/nrn2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodfellow M, et al. Estimation of brain network ictogenicity predicts outcome from epilepsy surgery. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29215. doi: 10.1038/srep29215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khambhati AN, Davis KA, Lucas TH, Litt B, Bassett DS. Virtual cortical resection reveals push-pull network control preceding seizure evolution. Neuron. 2016;91:1170–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlmann L, Grayden DB, Wendling F, Schiff SJ. Role of multiple-scale modeling of epilepsy in seizure forecasting. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;32:220–226. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Putten MJ, Zandt BJ. Neural mass modeling for predicting seizures. Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125:867–868. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jirsa VK, Stacey WC, Quilichini PP, Ivanov AI, Bernard C. On the nature of seizure dynamics. Brain. 2014;137:2210–2230. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson WS, Azhar F, Kudela P, Bergey GK, Franaszczuk PJ. Epileptic seizures from abnormal networks: Why some seizures defy predictability. Epilepsy Res. 2012;99:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei Y, Ullah G, Schiff SJ. Unification of neuronal spikes, seizures, and spreading depression. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11733–11743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0516-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traub RD, Contreras D, Whittington MA. Combined experimental/simulation studies of cellular and network mechanisms of epileptogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22:330–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wendling F, Hernandez A, Bellanger JJ, Chauvel P, Bartolomei F. Interictal to ictal transition in human temporal lobe epilepsy: Insights from a computational model of intracerebral EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22:343–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visser S, et al. Comparing epileptiform behavior of mesoscale detailed models and population models of neocortex. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;27:471–478. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181fe0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson HR, Cowan JD. Excitatory and inhibitory interactions in localized populations of model neurons. Biophys J. 1972;12:1–24. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(72)86068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson HR, Cowan JD. A mathematical theory of the functional dynamics of cortical and thalamic nervous tissue. Kybernetik. 1973;13:55–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00288786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ. The Wilson-Cowan model, 36 years later. Biol Cybern. 2009;101:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00422-009-0328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shusterman V, Troy WC. From baseline to epileptiform activity: A path to synchronized rhythmicity in large-scale neural networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2008;77(6 Pt 1):061911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.061911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nauhaus I, Busse L, Carandini M, Ringach DL. Stimulus contrast modulates functional connectivity in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:70–76. doi: 10.1038/nn.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuznetsov YA. Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory. Vol 112 Springer Science & Business Media; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lea-Carnall CA, Montemurro MA, Trujillo-Barreto NJ, Parkes LM, El-Deredy W. Cortical resonance frequencies emerge from network size and connectivity. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004740. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bower MR, Stead M, Meyer FB, Marsh WR, Worrell GA. Spatiotemporal neuronal correlates of seizure generation in focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lillis KP, et al. Evolution of network synchronization during early epileptogenesis parallels synaptic circuit alterations. J Neurosci. 2015;35:9920–9934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4007-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eissa T, et al. Multiscale aspects of generation of high-gamma activity during seizures in human neocortex. eNeuro. 2016;3:ENEURO.0141-15.2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0141-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreier JP, et al. COSBID study group Spreading convulsions, spreading depolarization and epileptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. Brain. 2012;135:259–275. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Drongelen W. Signal Processing for Neuroscientists. Elsevier; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schimmel H. The (+) reference: Accuracy of estimated mean components in average response studies. Science. 1967;157:92–94. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3784.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Drongelen W, Koch H, Marcuccilli C, Pena F, Ramirez JM. Synchrony levels during evoked seizure-like bursts in mouse neocortical slices. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1571–1580. doi: 10.1152/jn.00392.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhooge A, Govaerts W, Kuznetsof A. Matcont: A Matlab package for numerical bifurcation analysis of ODEs. ACM Trans Math Softw. 2003;29:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Destexhe A. Spike-and-wave oscillations based on the properties of GABAB receptors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9099–9111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09099.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirschstein T, Köhling R. What is the source of the EEG? Clin EEG Neurosci. 2009;40:146–149. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz B. Nerve, Muscle, and Synapse. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.