Abstract

Religion is a source of strength in Latina/o culture during challenging life transitions, such as the immigration process. Guided by a sociological stress–process model, this study examines relations between dimensions of religious coping, acculturative stress, and psychological distress among 530 young Latina women (ages 18–23 years) who recently immigrated to the United States (i.e., approximately 12 months prior to assessment). Higher levels of acculturative stress were associated with higher levels of psychological distress. Negative religious coping (i.e., the tendency to struggle with faith) moderated the relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress. Participants experiencing higher levels of acculturative stress reported greater psychological distress when they indicated more negative religious coping. Positive religious coping (i.e., the tendency to relate to faith with comfort and certainty) was not linked with acculturative stress or psychological distress. Implications for culturally tailored counseling interventions for this underserved and understudied population are discussed.

Keywords: Latina, Hispanic, religious coping, acculturative stress, psychological distress

The Latina/o immigrant population in the United States (U.S.) is rapidly growing, with approximately one-third consisting of first-generation immigrants (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Compared to U.S.-born Latinas/os and non-Latina/o Whites, Latina/o immigrants often face challenges that increase their risk for developing mental health problems (Alegría et al., 2008), including discrimination (Arellano-Morales et al., 2015; Arredondo, Gallardo-Cooper, Delgado-Romero, & Zapata, 2014), loss of familial and social support (Ornelas & Perreira, 2011), and reduced access to and utilization of healthcare resources (Hochhausen, Le, & Perry, 2011; Raymond-Flesch, Siemons, Pourat, Jacobs, & Brindis, 2014). Latina immigrants are particularly at risk for adverse mental health consequences from stress due to (a) conflicts between traditional and receiving cultures’ gender role expectations (Shattell, Quinlan-Colwell, Villaba, Iverns, & Mails, 2010), (b) stigma attached to seeking mental healthcare (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], 2017), and (c) intimate partner violence (Edelson, Hokoda, & Ramos-Lira, 2007).

Approximately 26% of Latina/os in the U.S. (aged 12 years and older) experienced depression from 2009–2012 in comparison to 21% in non-Latina/o Whites (Pratt & Brody, 2014). More than a third of U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinas living in the U.S. experience symptoms of depression, indicating higher-than-expected prevalence rates (Huang, Wong, Ronzio, & Yu, 2007). Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders increase with duration of residence for many foreign-born Latina/os, especially for younger women (Alegría et al., 2008; Perreira et al., 2015). Unfortunately, Latina immigrants are less likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to have access to, and receive, appropriate mental healthcare treatment (Hochhausen et al., 2011). Latina immigrants face barriers to care including lack of health insurance, reduced access to adequate health providers (Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008), and culturally insensitive barriers to treatment delivery (Driscoll & Torres, 2013).

Acculturative Stress Among Latina Adults

Acculturative stress consists of psychological and social stress experienced due to an incongruence of beliefs, values, and other cultural norms between a person’s country of origin and country of reception (Cabassa, 2003; Cuevas, Sabina, & Bell, 2012; Sanchez, Dillon, Concha, & De La Rosa, 2014; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). This form of stress also may be triggered by perceived feelings of inferiority, “otherness,” discrimination, language barriers, undocumented immigration status, or poverty (Berry, 1997; Finch & Vega, 2003; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Acculturative stress contributes to mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) among Latina/o immigrants (e.g., Driscoll & Torres, 2013; Ornelas & Perreira, 2011; Torres, 2010). Yet, to date, studies predominantly have examined health of Latina/o immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for several years or even generations (e.g., Dunn & O’Brien, 2009; Hochhausen et al., 2011), leaving a gap in the mental health literature about newly arrived young adult women. Relatively little is known about the mental health of newly arrived Latina young adults and how acculturative stress may influence their well-being during their initial years in the U.S.

Psychological distress is thought to potentially arise for immigrants when they are unable to successfully cope with acculturative stress (Crockett et al., 2007) and are exposed to social systems that “other,” marginalize, disempower, and exclude (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Such stress may be heightened during immigrants’ initial years of residence in the U.S., particularly when they (a) are less proficient in English, (b) have lower incomes, and (c) are separated from family and other social supports (Hovey & Magaña, 2002; Miranda & Matheny, 2000), as well as when they experience systemic social and economic inequalities and discrimination (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Therefore, in the present study we examined associations between acculturative stress and psychological distress experienced by Latina young adults who have immigrated to the U.S. within the past 3 years. More specifically, we investigated the potentially protective Latina/o cultural value of religious coping (reviewed next) in the lives of these women. Our research questions were guided by a sociological stress–process model (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981), which is a theoretical framework for conceptualizing health disparities as well as risk and protective health factors among minority populations. The model posits that health outcomes related to stress (e.g., acculturative stress) are contingent not only on the extent of stress exposure but also involve social, environmental, and personal resources (e.g., religious coping) that serve as potential mitigating influences on the link between stress and health outcomes such as psychological distress (Pearlin, 1989).

Religious Coping Among Latina Adults

Religion is a central part of Latina/o culture, informing beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and social interactions (Abraído-Lanza, Vasquez, & Echeverría, 2004; Steffen & Merrill, 2011). For example, many foreign-born and U.S.-born Latina/os enter the U.S. mental health system via clergy referrals, as opposed to referrals through primary care providers or self-referrals (Ruiz, 2002). In a study of religious observance among predominantly male Central American immigrants who had resided in the U.S. for an average of four years, 85% of participants reported identifying with some Christian denomination. Over 90% of the sample reported attending religious services, and over half of participants attended at least once per week (Dunn & O’Brien, 2009). Yet, religious coping is distinct from general religious observance because it refers to specific cognitive acts that emerge from a person’s religious beliefs that are used to deal with stressors (Tix & Frazier, 1998). Latina women in the U.S. tend to use religious coping more frequently than their non-Latina peers (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004). Use of religious coping is associated with less acculturation among foreign-born and U.S.-born Latinas in the U.S. (Mausbach, Coon, Cardenas, & Thompson, 2003). However, relatively little is known about the use of religious coping among Latina young adult immigrants during their transition from home country to the U.S. Questions regarding the extent to which contemporary young adult Latina women endorse traditional religious beliefs (e.g., coping) and observance (Pew Research Center, 2014), as well as the potentially protective role of religious coping against acculturative stress, remain unexamined.

The sociological stress–process model (Pearlin, 1989) is concerned with the extent to which mitigating personal, social, and institutional factors succeeds in constraining the frequency, severity, and diffusion of stressors in people’s lives. Latina immigrants may learn and internalize religious coping beliefs from social and institutional affiliations such as their families, churches, and other community institutions from which they immigrated (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Dunn & O’Brien, 2009). Latina young adult immigrants may practice learned religious coping to (a) manage the meaning of their immigration and acculturation experiences to reduce stress, and (b) keep their symptoms of stress within manageable bounds.

Two dimensions of religious coping—namely, positive and negative religious coping—have been posited to differentially affect mental health (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Pargament, 1997). Positive religious coping is considered adaptive and includes personal, internal cognitive coping efforts stemming from individuals’ constructive relationship with God or their faith (Kim, Kendall, & Web, 2015). It includes cognitive activities, such as seeking spiritual support from God and redefining stressors through a religious lens, as potentially beneficial (Kim et al., 2015; Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998; Szymanski & Obiri, 2010). Positive religious coping has been linked to positive mental health outcomes among research participants for whom religion is practiced and culturally sanctioned in times of stress, including African American adults (Holt, Lewellyn, & Rathweg, 2005; Reid & Smalls, 2004), a heterogeneous sample of low-income women (Olson, Trevino, Geske, & Vanderpool, 2012), a sample of religiously affiliated U.S. college students (Stoltzfus & Farkas, 2012), and a predominantly female sample of Central American adult immigrants (Hovey, 2000). In the only study that sampled Latina/o immigrants during their initial 12 months in the U.S., greater use of positive religious coping related to lower alcohol use (Sanchez et al., 2014). Positive religious coping also was linked with lower rates of depression and suicidal ideation among a predominantly female sample of Central American adult immigrants (Hovey, 2000). However, other researchers suggested a nonsignificant role for positive religious coping. Specifically, no indirect effect of positive religious coping was found on the positive link between racism and psychological distress among a sample of Christian Asian American students (Kim et al., 2015). Also, no relation between positive religious coping and well-being was found among a mostly non-Latina White sample of women with breast cancer (Hebert, Zdaniuk, Schulz, & Scheier, 2009).

Taken together, and consistent with the sociological stress–process model, past findings suggest that positive religious coping may play a role in buffering the effects of acculturative stress on psychological distress experienced by recent Latina young adult immigrants. The events of immigration, the acculturation process, and the potential systemic stressors experienced by recent Latina immigrants may prompt them to engage in culturally endorsed positive religious coping strategies to attempt to alter the emotional and cognitive meaning of their situations and reframe their experiences in a less threatening manner (Pearlin, 1989). Rather than feeling hopeless or distressed in response to stressors, the use of positive religious coping may allow individuals to feel supported and capable of overcoming current difficulties. That is, the use of positive religious coping may serve to indirectly manage symptoms of depression, anxiety, or general distress (e.g., Aranda, 2008) and keep the symptoms of stress produced by these experiences within manageable limits. Therefore, positive religious coping is anticipated to be a coping strategy that decreases the likelihood of experiencing psychological problems.

Negative religious coping is not coping per se, but rather refers to a person’s tendency to internally struggle with faith. It emerges from perceiving that one’s relationship with God is unstable (Kim et al., 2015; Pargament et al., 1998). Negative religious coping might include expressing or feeling dissatisfaction or hopelessness with God and/or the church, redefining stressors as acts of the Devil or as punishment from God, and questioning God’s power (Pargament et al., 1998). This form of religious coping is maladaptive and has been linked to poorer psychological adjustment, depression, and anxiety (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Olson et al., 2012; Pirutinsky, Rosmarin, Pargament, & Midlarsky, 2011; Szymanski & Obiri, 2010). Negative religious coping is associated with worse mental health among low-income women in the general U.S. population (Olson et al., 2012) and with greater acculturative stress among undocumented Latina/o adult immigrants during their initial year in the U.S. (Sanchez et al., 2014). Negative religious coping practices may include individual efforts to change the meaning of a stressor or the situation itself and reframe experiences in a less threatening manner to keep symptoms of stress within manageable bounds. However, when a person’s coping efforts do not successfully relieve stress, they may actually exacerbate the relation between a stressor and psychological distress (Szymanski & Obiri, 2010). For example, the frustration, struggle, and dissatisfaction that characterize negative religious coping might exacerbate the negative effects that acculturative stress has on psychological distress among recent Latina young adult immigrants.

The Present Study

The overarching aim of the present study is to identify whether two distinct religious coping styles (i.e., positive and negative) moderate relations between acculturative stress and psychological distress among recent Latina young adult immigrants. Based on the stress–process model and the reviewed literature, we tested three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Latina women reporting more acculturative stress, less positive religious coping, and more negative religious coping will indicate more psychological distress after accounting for participants’ age, time in the U.S. (months), education level, immigration status, and employment status. We included these covariates based on previous studies suggesting that lower socioeconomic status, more time in the U.S., and undocumented immigration status (documented versus undocumented) are associated with acculturative stress and psychological distress (e.g., Albrecht & McVeigh, 2012; Finch & Vega, 2003; Sanchez et al., 2014; Smith & Silva, 2011). Hypothesis 2: Positive religious coping will moderate the positive relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress while accounting for the aforementioned covariates. Specifically, the positive relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress will be weaker among Latinas who utilize more positive religious coping than those who endorse less positive religious coping.

Hypothesis 3: Negative religious coping will moderate the positive relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress while accounting for the aforementioned covariates. That is, the positive relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress will be stronger among Latinas who utilize more negative religious coping than those who report less negative religious coping.

Method

Recruitment and Procedure

For the present cross-sectional study, we analyzed baseline data from a longitudinal study of the social and cultural determinants of health in recent Latina young adult immigrants to the U.S. (Sheehan et al., 2016). An Institutional Review Board at a large public university in the Southeastern U.S. approved the study. Participant eligibility criteria included: (a) being a Latina woman aged 18–23 years, (b) having recently immigrated to the U.S. from a Latin American Country (i.e., within 36 months prior to baseline), and (c) intending to stay in the U.S. for at least four years (to facilitate data collection). Consent procedures and all interviews were conducted in Spanish by one of four bilingual Latina research assistants. We chose to conduct interviews with participants rather than administer self-report inventories to ensure comprehension of measures, build rapport, and encourage honest reporting of sensitive topics.

Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) was used to recruit participants. RDS has been found to be helpful in obtaining participants from “hidden” populations, such as immigrants and undocumented individuals (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2003). RDS involves asking each eligible participant (or seed) to recruit three others in her social network who meet study inclusionary criteria. Those participants who consent to participate then refer three others. This procedure is followed for up to five legs, at which point a new seed begins to avoid skewing the respondent sample with participants too closely socially interconnected.

Seed participants were recruited through advertisements at various community-based agencies (e.g., legal aid agencies, language schools), Latina/o health fairs and community events, and online postings (e.g., craigslist.org). Interested participants were screened for eligibility and, if eligible, scheduled for an interview. Interviews were held in a safe place chosen by participants or in university offices.

Sample

The sample consisted of 530 Latina young adult women who had recently immigrated to Miami-Dade county, Florida. The sample is unique in several ways. First, it consists of a distinctive and understudied group, namely newly arrived young adult Latina immigrants. The recent immigration status of the sample is an important element of the research design, as religious coping is used more readily among less acculturated Latina/os than acculturated Latina/os (Mausbach et al., 2003). Finally, the diverse Latina/o ethnic makeup of the study population is characteristic of the South Florida population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Participants’ ethnic identifications included Cuban (34%), followed by Colombian (11.1%), Nicaraguan (7.5%), Honduran (6.4%), Peruvian (5.6%), Mexican (5.1%), Venezuelan (4.9%), Ecuadorian (3.8%), Panamanian (3.6%), Dominican (3.0%), and 15% from nine other ethnicities (Argentinian, Bolivian, Chilean, Costa Rican, El Salvadorian, Guatemalan, Nicaraguan, Paraguayan, and Uruguayan).

On average, participants had resided in the U.S. for one year (SD = 9.94 months) at baseline assessment. Approximately 82% of participants were documented immigrants whereas approximately 18% were either undocumented, had an expired/tourist visa, or refused to answer the immigration status question. Participants’ ages ranged from 18–23 (M = 20.81, SD = 1.8). Primary motives for immigration were economic (57.9%), to reunite with family (28.6%), and political (5.3%). Ten percent of participants had less than a high school education. Fifty-seven percent received a high school diploma in their countries of origin. Twenty-seven percent indicated receiving a trade school degree in their countries of origin. Four percent reported receiving a Bachelor’s degree equivalent in their home countries. One percent of participants reported obtaining a postgraduate degree in their home countries. Approximately 66% were not employed, and hours worked per week varied (M = 32.63, SD = 10.50).

Measures

Selected measures were either validated in Spanish in previous research or were translated into Spanish for the present study. English versions of each measure went through a process of back translation, modified direct translation, and checks for semantic and conceptual equivalence to ensure accurate translation from English to Spanish (Behling & Law, 2000). For modified direct translations, a review panel consisting of individuals from various Latina/o subgroups representative of the Miami-Dade county Latina/o population was employed to address within-group variability.

Demographics

We assessed age (years), country of origin, formal education level, time in the U.S. (months), employment status, and immigration documentation status. Participants were asked to report their current immigration documentation status via 14 possible categories, including temporary or permanent resident; tourist, student, and temporary work visa; undocumented; and expired visa, asylum, and temporary protected immigrant. These categories were then recoded into a dichotomous variable (documented, undocumented) to facilitate analyses.

Acculturative Stress

The Social, Attitudinal, Familial, Environment Acculturative Stress Scale (SAFE; Mena, Padilla, & Maldonado, 1987) was used to measure acculturative stress. The SAFE is a 24-item measure that uses a 6-point Likert-type scale format (0 = did not happen, 1 = not at all, 5 = extremely stressful). Items on the SAFE include “I was insulted or treated poorly” and “members of my family cannot communicate in public places.” More acculturative stress is indicated by higher SAFE total scores. The potential range of total scores is 0 to 5. Latina/o samples’ responses on the SAFE total score indicated evidence of reliability, with reliability estimates between .90 and .95 (Fuertes & Westbrook, 1996; Hovey, 2000). We used a total SAFE score rather than subscale scores as suggested by Fuertes and Westbrook (1996) due to a lack of published evidence supporting a multidimensional factor structure. Evidence for convergent validity for the SAFE total score has been demonstrated with Latina/o samples (Fuertes & Westbrook, 1996). The present study sample responses on the SAFE total score suggested appropriate internal consistency (α = .97) for analyses.

Religious Coping

The Brief RCOPE (Pargament et al., 1998) is a measure of positive and negative religious coping styles. It contains 14 items measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 4 = a great deal). Participants indicated the extent to which they used various positive and negative religious coping acts to manage life stressors. Items include “sought help from God in letting go of my anger” (positive religious coping) and “wondered what I did for God to punish me” (negative religious coping). Mean scores for each subscale were used, with higher scores indicating more frequent use of positive or negative religious coping. The potential range of total scores for each subscale is one to four. Past samples have suggested adequate reliability estimates for both subscales (Pargament et al., 1998) as well as evidence for concurrent, incremental, and predictive validity for the measure (see Pargament, Feuille, & Burdzy, 2011, for a review). Furthermore, confirmatory factor analyses have supported a 2-factor structure among religious young adults (Kim et al., 2015), college students (Pargament et al., 1998), and Latina/o adult immigrants using a Spanish language version (Sanchez et al., 2014). Responses from Latina/o adult immigrants using a Spanish language version of the Brief RCOPE yielded Cronbach’s alphas of α = .95 for positive religious coping and .83 for negative religious coping (Sanchez et al., 2014). The present study samples’ responses demonstrated evidence of internal consistency for positive (α = .96) and negative religious coping (α = .97).

Psychological Distress

The validated Spanish version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Fitzpatrick, 2004) is a self-report measure consisting of 53 items in which participants rate the extent to which they have been bothered (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) in the past week by various symptoms. The present study utilized the Global Severity Index (GSI), which represents an overall level of mental health, with higher scores indicating more problematic functioning. The GSI is computed by calculating an average of subscale scores for all nine dimensions of the BSI and four additional items for a possible range of 0 to 4. Participant responses in psychometric validation studies using the English version of the BSI indicate adequate test-retest reliability (α = .90) and internal consistency for the GSI (Derogatis & Fitzpatrick, 2004). The BSI also demonstrates evidence of convergent validity with longer measures such as the SCL-90-R (with subscale correlations ranging from .92 to .99) in studies using the English language version. Studies of the Spanish version of the BSI with Latina/o samples have found evidence of construct validity (Hoe & Brekke, 2009) and internal consistency (Ruipérez, Ibáñez, Lorente, Moro, & Ortet, 2001). Present study participant responses yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .98.

Analytic Plan

The analytic plan consisted of three main steps. First, a bivariate correlation matrix was computed to assess potential multicollinearity among key observed study variables. Tabachnick and Fidell (2013) suggested that to avoid multicollinearity, correlation coefficients between predictors should be less than .70. The second step consisted of examining the correlation matrix of all hypothesized predictor variables and covariates to identify significant correlates of psychological distress to be used in subsequent analyses. The third step involved entering each of the selected predictor variables into a multiple regression analysis predicting direct and moderating effects on psychological distress.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics of predictor and dependent variables are presented in Table 1. Acculturative stress was negatively related to negative religious coping and positively linked with psychological distress. Positive religious coping was positively related to negative religious coping and psychological distress. Negative religious coping was also positively correlated with psychological distress. None of the hypothesized covariates (country of origin, employment, income, documentation status, formal education level, time in the U.S., or age) were correlated with psychological distress. In addition, no predictor variables were deemed too highly correlated and at risk for multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Predictor and Dependent Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acculturative Stress | — | 1.44 | 1.32 | |||

| 2. Positive Religious Coping | .02 | — | 2.76 | .88 | ||

| 3. Negative Religious Coping | −.24** | .53** | — | 1.90 | 1.00 | |

| 4. Psychological Distress | .29** | .12** | .18** | — | .34 | .67 |

p < .01.

p < .001.

To test direct effects and moderation hypotheses via multiple regression analysis, we first standardized the predictor and proposed moderators (positive and negative religious coping) to reduce potential multicollinearity in testing moderation (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). We created two-way interaction terms for each proposed moderator with acculturative stress. We entered the direct effects of acculturative stress, positive and negative religious coping in block 1 of regression analysis, and the interaction terms in block 2. Results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the Moderating Effects of Positive and Negative Religious Coping on the Relation Between Acculturative Stress and Psychological Distress

| Predictor | B | β | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | ||||

| Constant | .33 | — | .03 | <.001 |

| Acculturative Stress | .23 | .34 | .03 | <.001 |

| Positive Religious Coping | −.03 | −.04 | .04 | .39 |

| Negative Religious Coping | .20 | .30 | .03 | <.001 |

| R2 = .14 | ||||

| F for ΔR2 = 28.60, p < .001 | ||||

| Block 2 | ||||

| Constant | .38 | — | .03 | <.001 |

| Acculturative Stress | .17 | .25 | .03 | <.001 |

| Positive Religious Coping | .01 | .01 | .03 | .92 |

| Negative Religious Coping | .20 | .30 | .03 | <.001 |

| Acculturative Stress × Positive Religious Coping | −.02 | −.03 | .03 | .60 |

| Acculturative Stress × Negative Religious Coping | .19 | .32 | .03 | <.001 |

| R2 = .22 | ||||

| ΔR2 = .08 | ||||

| F for ΔR2 = 27.59, p < .001 |

Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Acculturative stress and negative religious coping were found to positively associate with psychological distress. Positive religious coping did not associate with psychological distress when accounting for other direct effects.

In Hypothesis 2, we predicted that positive religious coping would moderate the relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress. However, as with the direct effect of positive religious coping, the interaction between positive religious coping and acculturative stress did not associate with psychological distress.

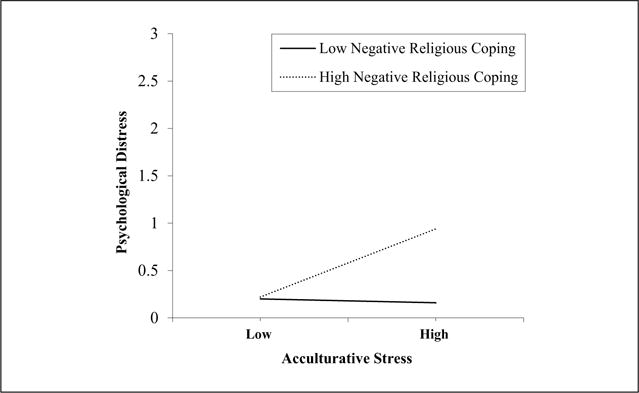

In Hypothesis 3, we predicted that negative religious coping would moderate the relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress. The interaction of negative religious coping and acculturative stress significantly contributed to the moderation model to predict psychological distress. Thus, for Hypothesis 3, a moderation effect of negative religious coping was observed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Moderating role of negative religious coping on relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress.

Direct effects of acculturative stress and positive and negative religious coping explained approximately 14% of the variance in psychological distress. The addition of the interaction effects between acculturative stress and positive and religious coping explained approximately 8% of incremental variance in psychological distress.

Discussion

Our study provided further evidence for the direct relation between acculturative stress and psychological distress specifically among recent Latina young adult immigrants. Findings also indicate that engagement in negative religious coping seems to exacerbate the positive link between acculturative stress and psychological distress in this population. This finding is congruent with the sociological stress–process model’s notion that health outcomes due to stress are influenced not just by the extent of stress exposure, but also by a person’s coping resources (Pearlin, 1989). However, contrary to this theory, positive religious coping was not related to psychological distress. Thus, the assertion that personal resources, such as religious coping efforts, are protective against the effects of stress on health outcomes was not supported in the current sample. This result also is divergent with findings on the protective nature of positive religious coping among Latina/o adult immigrants and general populations (e.g., Sanchez et al., 2014; Stoltzfus & Farkas, 2012). The remainder of this section describes the subsequent unique contributions and implications of the present study.

Negative Religious Coping

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Chatters, 2000; Fitchett et al., 2004; Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000; Pargament et al., 1998; Pirutinsky et al., 2011; Sanchez et al., 2014; Szymanski & Obiri, 2010) and the sociological stress–process model, we found that negative religious coping exacerbated the positive link between acculturative stress and psychological distress among our sample. Negative religious coping, characterized by feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and disillusionment with one’s religion, may create a maladaptive cognitive style in which ineffective coping leads to greater feelings of distress and exasperation. Generally speaking, coping efforts are intended to manage symptoms of stress and change the personal meaning of either stressful experiences or the stressful situation itself (Pearlin, 1989). However, negative religious coping efforts may change the meaning of stress in a way that increases feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and distress. Future research should examine not only which aspects of negative religious coping differentially impact psychological distress, but also the potential individual, social, and cultural factors that lead to individual differences in adherence to negative religious coping among Latina/o immigrants. Finally, it is important to note that unassessed mental health problems may have precipitated the increased use of negative religious coping among participants, and that these maladaptive coping strategies may have arisen from preexisting distress. Longitudinal research is needed to elucidate the temporal order of psychological distress and religious coping strategies among Latina/os across the acculturation spectrum (i.e., recently immigrated—U.S.-born).

Positive Religious Coping

The lack of association found between positive religious coping and psychological distress in the regression analysis is similar to past studies that conceptualized and measured the construct in the same way as the present study (Hebert et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2015). These findings may be due, in part, to unexamined indirect effects of social, cultural, and contextual variables. Such an explanation is suggested not only by the stress–process model (Pearlin, 1998) but also by scholars calling for a more complex examination of multiple structural and contextual factors that affect the health of Latino immigrants (e.g., social and economic inequalities and discrimination; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). For example, the current sample was unique in terms of several demographic characteristics: young adult age range, relatively high education levels, residing in a high Latino/a ethnic density region of the U.S. These factors may explain differential engagement in religious coping in response to stress. That is, research has indicated that younger Latina immigrants—particularly those who are documented—may be less likely to endorse and utilize traditional religious beliefs and practices than past generations (Pew Research Center, 2014; Sanchez et al., 2014). Hence, although religion is considered a core feature of Latina/o cultural values, the use of religious coping may vary across age groups, socioeconomic status, country of origin, contexts, and the lifespan. Future research would benefit from assessing religious beliefs and practices among population-based samples of Latina immigrants more broadly to determine how such beliefs vary with complex intersecting factors such as age, region, racial group membership, documentation status, stress due to discrimination, and numerous other relevant social, cultural, and structural moderators.

Women in the present study who were experiencing stressors due to immigration and acculturation also may have been relying on unexamined social and institutional supports other than religion to cope (e.g., family, friends, neighborhood supports; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Future studies are needed to investigate a wider range of potential coping strategies to identify effective ways to reduce distress. Furthermore, in terms of construct measurement, it may be that the selected measure of positive religious coping did not assess the full range of positive religious coping practiced by participants. Positive religious coping items in our study only reflected individual acts of cognitive restructuring (e.g., “I tried to see how God may be trying to make me stronger in the situation,” or “I focused on religion to try to stop worrying about my problems”). Thus, future research may benefit from expanding the scope of this construct to include more collectivistic behaviors and religious observances. Finally, the lack of positive religious coping effects on distress may have been due to participants’ recent arrival to the U.S. That is, women in the present study may not have been in the U.S. long enough to connect with churches or religious institutions, thereby negating opportunities for engagement in sufficient positive religious coping to influence distress levels. Future longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether increases in positive religious coping inversely relate to distress in this population over time.

Potential Implications for Research and Practice

Although the Latina/o immigrant experience is receiving increased attention within the counseling psychology literature (e.g., Chavez-Korell & Torres, 2014; Flores et al., 2011; Liang, Salcedo, Rivera, & Lopez, 2009; Moradi & Risco, 2006), there remains a gap in empirical knowledge concerning specific cultural norms and values of Latina/o immigrants. Our findings have important implications for counseling psychologists who will increasingly work with recent Latina immigrants given (a) the projected increase of Latina/os in the U.S. population as well as (b) our field’s social justice efforts to reduce mental health disparities among this underserved population.

Existing conceptual and empirical literature (e.g., Alegría et al., 2008; Arellano-Morales et al., 2015; Arredondo et al., 2014; Crockett et al., 2007; Finch & Vega, 2003; Krogstad & López, 2016; Ornelas & Perreira, 2011; Perreira et al., 2015; Sanchez et al., 2014; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007) suggest myriad social and structural reasons for Latina immigrants’ psychological distress (e.g., discrimination, poverty, lack of familial and social support, documentation status). Because of the relative underrepresentation of recent Latina immigrants in counseling psychology research and the limited scope of the present study, future studies are needed to continue exploring mitigating factors (e.g., neighborhood factors like ethnic density or regional differences; Shaw et al., 2012) that may differentially influence Latina mental health. Understanding such potential processes may help counselors develop effective case conceptualizations and treatment plans to address mental health issues disproportionately affecting Latina immigrants in the U.S. For instance, psychoeducational interventions and prevention efforts around acculturative stress, cultural beliefs, and structural injustice could help inform communities and clients of risks and protective strategies to support Latina immigrants’ mental health.

Contrary to the common perception that religious beliefs and practices are universally protective cultural values that may help individuals more effectively handle difficulties in their lives (e.g., Pargament et al., 1998), our findings are consistent with those of others that suggest the need for a more nuanced understanding of religious coping (e.g., Hebert et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2015). In general, counseling psychologists have been encouraged to enhance their skills, comfort, and knowledge of religious and spiritual issues within the counseling process (e.g., Hoogestraat & Trammel, 2003; Schulte, Skinner, & Claiborn, 2002). This skill may be especially required to practice effectively with recent Latina immigrants. Our findings suggest that negative religious coping attempts may signal greater distress in some cases in this population. Counselors should be able to assess for potential negative religious coping in the lives of recent Latina young adult immigrants during the intake assessment process. Counselors’ case conceptualizations of Latina young adult immigrant clients should integrate the incidence and role of negative religious coping in terms of presenting concerns. More specifically, counselors are encouraged to attend to potential links between negative religious coping attempts and clients’ well-being as part of the treatment planning and intervention selection. For instance, with the help of counselors, clients’ maladaptive religious coping beliefs could be disentangled from adaptive religious efforts to reduce distress while maintaining the culturally endorsed practice of religious coping (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Mausbach et al., 2003). Furthermore, as suggested by Szymanski & Obiri (2010), counselors can use religious assessments like the Brief RCOPE (Pargament et al., 1998) as well as less structured interviews to better understand how clients use religion and spirituality to cope with stressors and how they relate to their faith. Equipped with a better understanding of a client’s relationship to her spirituality, counseling psychologists can help Latina immigrants explore how negative religious coping might influence psychological distress and help develop more adaptive coping.

Limitations

Despite its contributions, our study has limitations that inform future research and counseling. First, although the use of RDS has been successful for recruiting hidden populations such as undocumented immigrants (Passel & Cohn, 2011), it does not ensure representative sampling. Second, although efforts were made to recruit participants from major Latina/o subgroups, some groups were represented more than others due to their representation in South Florida in general (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Thus, the sample was representative of Latinas/os living in South Florida but not the larger U.S. Future research is encouraged to sample from larger geographical locales and explore potential regional differences in acculturative stress, the practice of religious coping, and psychological well-being. Third, participants did not complete a measure of overall religiosity. Although religiosity pervades Latina/o culture (Dunn & O’Brien, 2009; Steffen & Merrill, 2011) and many Latina/os use religious coping to deal with stress (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Mausbach et al., 2003), a measure of self-reported religiosity or the relative importance of religion to one’s life might better explain some of the variance in behavioral religious coping practices. Finally, the emerging literature suggests that negative and positive religious coping might consist of various strategies that differentially affect mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., Kim et al., 2015). Future research needs to consider active (e.g., religious-based behaviors) versus passive (e.g., religious-based attitudes or beliefs) religious coping strategies that were not specified in the present study.

Our study highlighted the consequences of acculturative stress for Latina young adults and the moderating effects of negative religious coping on mental health problems during their first years in the U.S. We believe that our findings distinctively contribute to the growing body of literature examining acculturative stress, mental health, and related health behaviors among Latina/o immigrants in the U.S. and provide counseling psychologists with information to address the negative impact of acculturative stress on the health of this rapidly growing and often marginalized population.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Arnaldo Gonzalez, Melissa Ertl, and Yajaira Cabrera Tineo for editorial assistance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by award number P20MD002288 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Nicole Da Silva, BA, is a doctoral student in the Counseling Psychology PhD program in the Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology at the University at Albany–SUNY. Her research interests center around the influences of sociocultural factors on mental health and service utilization among Latinos. She is particularly interested in the relations between cultural values and gender roles on health outcomes for Latina adults.

Frank R. Dillon, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology at the University at Albany–SUNY. His research focuses on health disparities and mental health issues affecting racial, ethnic, and sexual minority groups in the United States. A principal theme of his scholarship is elucidating cultural and social determinants of substance use disorders and HIV risk behaviors.

Toni Rose Verdejo, MS, is a graduate of the Mental Health Counseling program, Division of Counseling Psychology at the University at Albany, SUNY. Her research interests include health disparities among Latinxs, intimate partner violence among Latinas, and the influence of Latina gender roles on psychological distress.

Mariana Sanchez, PhD, is a postdoctoral research associate at the Center for Research on U.S. Latino HIV/AIDS & Drug Abuse at Florida International University. The overarching aim of her research agenda is the development of culturally relevant prevention programs aimed at reducing and ultimately eliminating substance abuse health disparities among Latinos. To date, her research has focused on examining how sociocultural determinants impact substance use risk and protective behaviors among vulnerable and underserved Latino populations (e.g., recent and undocumented immigrants, farm workers).

Mario De La Rosa, PhD, is a professor in the Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work and Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University. He is the founding director of the university’s Center for Research on U.S. Latino HIV/AIDS and Drug Abuse, and is an expert in the areas of Latino substance abuse, substance use as a risk factor for HIV/AIDS, violence, and cross-cultural issues. Currently, Dr. De La Rosa’s research focuses on the sociocultural factors influencing substance abuse and HIV risk behaviors among adult Latina immigrants as well as the impact of pre-immigration factors on the alcohol use behaviors of recent young adult Latino immigrants.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Note

Preliminary findings from this study were presented as a poster at the American Psychological Association in Toronto in August 2015.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Vasquez E, Echeverría SE. En las Manos de Dios [In God’s Hands]: Religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:91–102. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht SS, McVeigh KH. Investigation of the disparity between New York City and national prevalence of nonspecific psychological distress among Hispanics. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9:1101–1004. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, Meng XL. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP. Relationship between religious involvement and psychological well-being: A social justice perspective. Health & Social Work. 2008;33:9–21. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P, Gallardo-Cooper M, Delgado-Romero EA, Zapata AL. Culturally responsive counseling with Latinas/os. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Morales L, Roesch SC, Gallo LC, Emory KT, Molina KM, Gonzalez P, Brondolo E. Prevalence and correlates of perceived ethnic discrimination in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos sociocultural ancillary study. Journal of Latino Psychology. 2015;3:160–176. doi: 10.1037/lat0000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behling O, Law KS. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: Problems and solutions. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; 2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:127–146. doi: 10.1177/0739986303025002001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and health: public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publ-health.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Korell S, Torres L. Perceived stress and depressive symptoms among Latino adults: The moderating role of ethnic identity cluster patterns. The Counseling Psychologist. 2014;42:230–254. doi: 10.1177/0011000013477905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinley M, Raffaelli M, Carlo G. Acculturative stress, social support and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:347–355. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Fitzpatrick M. The SCL-90-R, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), and the BSI-18. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. 3rd. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll MW, Torres L. Acculturative stress and Latino depression: The mediating role of behavioral and cognitive resources. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19:373–382. doi: 10.1037/a0032821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MG, O’Brien KM. Psychological health and meaning in life: Stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009;31:204–227. doi: 10.1177/0739986309334799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson MG, Hokoda A, Ramos-Lira L. Differences in effects of domestic violence between Latina and non-Latina women. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10896-006-9051-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BF, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/A:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, Gibbons JL, Cameron JR, David JA. Religious struggle: Prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2004;34:179–196. doi: 10.2190/ucj9-dp4m-9c0x-835m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in psychological research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;15:115–134. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores LY, Mendoza MM, Ojeda L, He Y, Rosales R, Medina V, Varvel SJ. A qualitative inquiry of Latino immigrants’ work experiences in the Midwest. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:522–536. doi: 10.1037/a0025241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes JN, Westbrook FD. Using the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental (SAFE) Acculturation Stress Scale to assess the adjustment needs of Hispanic college students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 1996;29:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert R, Zdaniuk R, Schulz R, Scheier M. Positive and negative religious coping and well-being in women with breast cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2009;12:537–545. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhausen L, Le H, Perry DF. Community-based mental health service utilization among low-income Latina immigrants. Community Mental Health. 2011;47:14–23. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe M, Brekke J. Testing the cross-ethnic construct validity of the brief symptom inventory. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19:93–103. doi: 10.1177/1049731508317285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogestraat T, Trammel J. Spiritual and religious discussions in family therapy: Activities to promote dialogue. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2003;31:413–426. doi: 10.1080/01926180390224049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Lewellyn LA, Rathweg MJ. Exploring religion-health mediators among African-American parishioners. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:511–527. doi: 10.1177/1359105305053416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among Central American immigrants. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:125–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, Magaña CG. Psychosocial predictors of anxiety among immigrant Mexican migrant farmworkers: Implications for prevention and treatment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:274–289. doi: 10.1037//1099-9809.8.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PY, Kendall DL, Webb M. Religious coping moderates the relation between racism and psychological well-being among Christian Asian-American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62:87–94. doi: 10.1037/cou0000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, López G. Roughly half of Hispanics have experienced discrimination. 2016 Jun 29; Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/29/roughly-half-of-hispanics-have-experienced-discrimination/

- Liang CT, Salcedo J, Rivera AL, Lopez MJ. A content and methodological analysis of 35 years of Latino/a-focused research. The Counseling Psychologist. 2009;37:1116–1146. doi: 10.1177/0011000009338496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Cardenas V, Thompson LW. Religious coping among Caucasian and Latina dementia caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2003;9:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mena FJ, Padilla AM, Maldonado M. Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:207–225. doi: 10.1177/07399863870092006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Matheny KB. Socio-psychological predictors of acculturative stress among Latino adults. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2000;22:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Risco C. Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:411–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Latino mental health. Arlington, VA: 2017. Retrieved from http://www.nami.org/Find-Support/Diverse-Communities/Latino-Mental-Health. [Google Scholar]

- Olson MM, Trevino DB, Geske JA, Vanderpool H. Religious coping and mental health outcomes: An exploratory study of socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2012;8:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM. The role of migration in the development of depressive symptoms among Latino immigrant parents in the USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2:51–76. doi: 10.3390/rel2010051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:710–724. doi: 10.2307/1388152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D. Unauthorized immigrant populations: National and state trends 2010. Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/133.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:237–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Gotman N, Isasi CR, Arguelles W, Castaneda SF, Daviglus ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Mental health and exposure to the United States: Key correlates from the Hispanic Community Health Study of Latinas. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2015;203:670–678. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The shifting religious identity of Latinos in the United States. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/files/2014/05/Latinos-and-Religion-05-06-full-report-final.pdf.

- Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Midlarsky E. Does negative religious coping accompany, precede, or follow depression among Orthodox Jews? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;132:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the US household population, 2009–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. (NCHS data brief No. 172). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond-Flesch M, Siemons R, Pourat N, Jacobs K, Brindis CD. “There is no help out there and if there is, it’s really hard to find”: A qualitative study of the health concerns and health care access of Latino “DREAMers”. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid TL, Smalls C. Stress, spirituality, and health promoting behaviors among African-American college students. Journal of Black Western Studies. 2004;28:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ruipérez M, Ibáñez MI, Lorente E, Moro M, Ortet G. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the BSI: Contributions to the relationship between personality and psychopathology. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2001;17:241–250. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.17.3.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz P. Commentary: Hispanic access to health/mental health services. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2002;73:85–91. doi: 10.1023/A:1015051809607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2003;34:193–240. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Dillon FR, Concha M, De La Rosa M. The impact of religious coping on the acculturative stress and alcohol use of recent Latino immigrants. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;4:1986–2004. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9883-6.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte DL, Skinner TA, Claiborn CD. Religious and spiritual issues in counseling psychology training. The Counseling Psychologist. 2002;30:118–134. doi: 10.1177/0011000002301009.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger J, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattell MM, Quinlan-Colwell A, Villaba J, Iverns NN, Mails M. A cognitive-behavioral group therapy intervention with depressed Spanish-speaking Mexican women living in an emerging immigrant community in the United States. Advances in Nursing Science. 2010;33:158–169. doi: 10.1097/ans.0b013e3181dbc63d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Atkin K, Bécares L, Albor CB, Stafford M, Kiernan KE, Pickett KE. Impact of ethnic density on adult mental disorders: Narrative review. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;201:11–19. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DM, Dillon FR, Babino R, Melton J, Spadola C, Da Silva N, De La Rosa M. Recruiting and assessing young adult Latina recent immigrants in health disparities research. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development. 2016;44:245–262. doi: 10.1002/jmcd.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Silva L. Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen P, Merrill R. The association between religion and acculturation in Utah Mexican immigrants. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2011;14:561–573. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2010.495747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus KM, Farkas K. Alcohol use, daily hassles, and religious coping among students at a religiously affiliated college. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47:1134–1142. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.644843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Obiri O. Do religious coping styles moderate or mediate the external and internalized racism-distress links? The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;39:438–462. doi: 10.1177/0011000010378895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tix AP, Frazier PA. The use of religious coping during stressful life events: Main effects, moderation, and mediation. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:411–422. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L. Predicting levels of Latino depression: Acculturation, acculturative stress, and coping. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:256–263. doi: 10.1037/a0017357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Decennial Census 2000 and 2010. Miami-Dade County Department of Planning and Zoning; Miami, FL: 2011. Retrieved from https://www.miamidade.gov/planning/library/reports/2010-census-commission-district.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey demographic and housing estimates. 2017 Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_5YR_DP05&prodType=table.

- Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]