Abstract

Inhaled hydrogen gas (H2) provides protection in rat models of human acute lung injury (ALI). We previously reported that biomarker imaging can detect oxidative stress and endothelial cell death in vivo in a rat model of ALI. Our objective was to evaluate the ability of 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamineoxime (HMPAO) and 99mTc-duramycin to track the effectiveness of H2 therapy in vivo in the hyperoxia rat model of ALI. Rats were exposed to room air (normoxia), 98% O2 + 2% N2 (hyperoxia) or 98% O2 + 2% H2 (hyperoxia+H2) for up to 60 hrs. In vivo scintigraphy images were acquired following injection of 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin. For hyperoxia rats, 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin lung uptake increased in a time-dependent manner, reaching a maximum increase of 270% and 150% at 60 hrs, respectively. These increases were reduced to 120% and 70%, respectively, in hyperoxia+H2 rats. Hyperoxia exposure increased glutathione content in lung homogenate (36%) more than hyperoxia+H2 (21%), consistent with increases measured in 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake. In 60-hr hyperoxia rats, pleural effusion, which was undetectable in normoxia rats, averaged 9.3 gram/rat, and lung tissue 3-nitrotyrosine expression increased by 790%. Increases were reduced by 69% and 59%, respectively, in 60-hr hyperoxia+H2 rats. This study detects and tracks the anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic properties of H2 therapy in vivo after as early as 24 hrs of hyperoxia exposure. The results suggest the potential utility of these SPECT biomarkers for in vivo assessment of key cellular pathways in the pathogenesis of ALI and for monitoring responses to therapies.

Keywords: Hyperoxia, SPECT imaging, acute respiratory distress syndrome, 99mTc-HMPAO, 99mTc-durmaycin

INTRODUCTION

Acute lung injury (ALI) is one of the most frequent causes of admission to medical intensive care units (1,2). Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) occurs in ~250,000 patients/year in the U.S., carries a mortality rate that may exceed 40%, lacks early detection tools and has limited therapies (1,2). The most common therapy is ventilation with high concentrations of oxygen (hyperoxia) (3). However, sustained exposure to high fractions of oxygen causes ARDS (4). Thus the development of novel diagnostics and therapies for treating patients with ARDS is urgently needed.

Recent preclinical studies have demonstrated that inhaled hydrogen gas (H2) at a concentration of ~2% provides protection in lung injury animal models of human ALI/ARDS (e.g. ventilation-induced injury, transplant-induced ischemia-reperfusion injury, lipopolysaccharide, and hyperoxic injury) (5–10), attributed to its potent anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties. H2 reduces the most damaging oxidants such as hydroxyl radical and peroxynitrite, but has no effect on superoxide, nitric oxide, or hydrogen peroxide and hence does not interfere with their role in cell signaling and/or immune response (5,8). Additional studies have shown that the anti-apoptotic properties of H2 are associated with inhibition of caspase 3 activation (8). Moreover, H2 is highly diffusible (6,8), and hence can readily reach subcellular compartments that are targets of oxidative stress, including mitochondria.

Recently we demonstrated the utility of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) biomarker imaging to detect oxidative stress (using 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (HMPAO)) and endothelial cell death (using 99mTc-duramycin) in lungs of rats exposed to high concentrations of O2 (hyperoxia) or treated with the endotoxin lipopolysaccharide as models of human ALI/ARDS (8,11–13). Furthermore, we identified a strong correlation between 99mTc-HMPAO uptake and glutathione tissue content (12), as an indicator of oxidative stress, and between 99mTc-duramycin uptake and cleaved-caspase 3 as a marker of apoptosis (11,14). The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential utility of 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin to track the effectiveness of H2 therapy in vivo in the hyperoxia rat model of human ALI/ARDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

HMPAO (Ceretec®) was purchased in kit form from GE Healthcare (Arlington Heights, IL), and technetium-labeled macroaggregated albumin (99mTc-MAA, particle sizes 20 – 40 μm) was purchased from Cardinal Health (Wauwatosa, WI). Antibodies to 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (Abcam, # ab52309), and keratin 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (Abcam, # ab46545) were used with appropriate secondary antibodies (mouse 1:3000 for 3-NT and rabbit 1:3000) to measure expression of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) in lung tissue homogenate. Diethyl maleate (DEM) and other reagent grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Rat model of human ALI/ARDS

All treatment protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center, the Medical College of Wisconsin and Marquette University.

For normoxia (control) rat studies, adult (68–77 days old) male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River; 351±3 (SE) g, n = 42) were exposed to room air in chambers side by side with those exposed to hyperoxia. For hyperoxia studies, age- and weight-matched rats (341±3 g, n = 77) were housed in a Plexiglass chamber and exposed to 98% O2 + 2% N2 (pure oxygen mixed with air) for 24 hrs, 48 hrs, or 60 hrs as previously described (12). To evaluate the therapeutic effect of 2% H2, age-matched rats (344±3 g, n = 62) were housed similarly but exposed to 98% O2 + 2% H2 (Praxair Inc., Danbury, CT) for 24 hrs, 48 hrs, or 60 hrs. For all hyperoxia and hyperoxia+H2 experiments, the O2 concentration in the chamber was measured using a DD103 DrDAQ Oxygen Sensor (Pico Technology, Cambridgeshire, UK) and was determined to be > 96%. For the hyperoxia+H2 experiments, the H2 concentration in the chamber was measured using a portable hydrogen detector (Model # 7200P, U.S. Industrial Products Co., Cypress, CA) and determined to be >1.8%.

Lung wet-to-dry weight ratio, weight of pleural effusion

Heart and lungs from a randomly selected subset of each group of rats were isolated as previously described (12). The lungs were dissected free of the heart, trachea and mainstem bronchi and total lung wet weight was obtained. The left lung lobe was weighed and dried at 60°C for wet-to-dry weight ratio and the remaining lung lobes were used for the histological studies described below (12).

For a subset of rats exposed to hyperoxia or hyperoxia+H2, pleural effusion within the chest cavity was determined by inserting cotton gauze into the chest cavity to absorb any pleural effusion (11). The gauze was weighed before and after use and the difference in weights was used to measure pleural effusion.

Histology

In a randomly selected subset of rats with normoxia (n=4), 48-hr hyperoxia (n=5), 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 (n=5), 60-hr hyperoxia (n=5), and 60-hr hyperoxia+H2 (n=4) lungs were fixed after inflation in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) and embedded in paraffin. Whole-mount sections of lung were cut (4 μm thick), processed and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E, Richard Allan, Kalamazoo, MI). Using high resolution jpeg images of the slides, an investigator masked to the treatment groups obtained 3–4 representative images from pre-selected areas of the lung on each slide, avoiding large vessels or airways at 100X (for neutrophils and edema) and 400X (for alveolar septum thickness). These images were then scored independently and values for each rat averaged for a single “n”. We used a 0–2 scoring system for neutrophil influx, edema, and thickness of the diffusion barrier (Table 1) recommended by Matute-Bello et al. (15).

Table 1.

Endpoints for histological injury grading on a scale of 0–2 for each of the indices of injury, including neutrophilic influx, edema, and thickness of the alveolar septum.

| Histology Injury endpoint/score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophilic influx | None to very rare | Perivascular or peribronchiolar only | intra-alveolar and widely distributed |

| Edema | None to very rare | Proteinacious material in <5% and <20% field | proteinacious material in > 20% field |

| Thickness of alveolar septum | ≤1.8 × control thickness | >1.8 but < 2.5 × control thickness | > 2.5 × control thickness |

Western blots

Western blot analysis was carried out as previously described (16) on whole lung tissue homogenate (protein concentration 30 μg/μl) to quantify the expressions of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (17) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (18) as indicators of oxidative stress. The following primary antibodies (Abcam) were used: 3-NT ab52309 and 4-HNE ab46545 with appropriate secondary antibodies.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

Representative rats from normoxia, 48-hr hyperoxia, and 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 groups were anesthetized with Beuthanasia (40–50 mg/kg i.p.). The trachea was cannulated, the chest opened, and the heart and lungs were removed from the thoracic cavity. The lungs were infused through the trachea with 3 ml of ice-cold, Ca2+-free phosphate-buffered saline ex vivo (12). The solution was withdrawn and saved for analysis. The procedure was repeated with a second volume of 3 ml for a total instilled lavage of 6 ml. The returned BAL volume was measured and the cells resuspended by gentle agitation. An aliquot (1 ml) was removed for determination of total cell counts and protein concentration in the cell-free supernatant. The remainder of the sample was used for cytospin preparations. Cell counts were obtained by resuspending cell pellet from 1 ml after centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 minutes in a known volume and counting with a hemocytometer (12).

Mitochondrial membrane potential

Representative rats from the normoxia, 48-hr hyperoxia, and 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 groups were anesthetized, and the lungs rapidly exposed and cleared of residual blood with 50 ml cold perfusion solution (physiologic saline buffered with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and containing 5.5 mM glucose) via the right ventricle. The lungs were then removed from the chest, trachea, large airways and large vessels were removed, after which the peripheral lung was placed in an ice-cold homogenization buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM HEPES, 200 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 1 mM EFTA, 2% fatty acid-free BSA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (50 μl/g lung tissue; set III, Calbiochem) and minced over ice. Lung tissue was homogenized using a Tissue Tearer Homogenizer. The resulting homogenate was then centrifuged (Sorvall Superspeed RC-5B, Norwalk, CT) at 2,000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and centrifuged at 17,800 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The resulting supernatant was discarded and the remaining pellet was resuspended in 5 ml ice-cold homogenization solution and centrifuged at 17,800 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the final pellet was resuspended in 0.3–4 ml ice-cold buffer (same as the homogenization buffer without BSA or the protease inhibitor cocktail) and stored on ice to be used for membrane potential studies. Mitochondrial protein was determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) studies were performed at room temperature using a Photon Technology International (PTI) QuantaMaster fluorometer (HORIBA Scientific, Edison, New Jersey) that monitored and recorded the rhodamine (R123) emission signal (503/527 nm excitation/emission wavelength) continuously over time (19). Briefly, a cuvette containing 1 ml of the reaction buffer (pH 7.2), R123 (200 nM), and either pyruvate (10 mM) + malate (5 mM) or succinate (7 mM) was placed on the stage of the fluorometer. After 2 minutes, mitochondrial protein (1mg/ml) was added, and then once the R123 emission signal reached steady-state (state 2), ADP (100 or 50 μM) was added to evaluate the ADP-stimulated depolarization of ΔΨm. The uncoupled ΔΨm was then determined by adding carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) henylhydrazone (FCCP, 10 μM). The emission signal was then normalized to its final value reached after the addition of FCCP (19).

Glutathione (GSH) content

Lungs of randomly selected normoxia, 48-hr hyperoxia, and hyperoxia + H2 rats were isolated, connected to a ventilation-perfusion system, and washed free of blood using Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate perfusate containing (in mM) 4.7 KCl, 2.51 CaCl2, 1.19 MgSO4, 2.5 KH2PO4, 118 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 5.5 glucose, and 5% bovine serum albumin as previously described (12,20). Total lung wet weight was obtained then a portion of the lung was used for the glutathione assay. The 48-hr time point was chosen since at this time the increase in HMPAO lung uptake is large enough to evaluate the impact of H2 on GSH content without significant cellular infiltration observed at the 60-hr time point.

Lung tissue was dissected free from large airways and connective tissue, and weighed. The tissue was then placed into 10 volumes (per lung wet weight) of 4°C sulfosalicylic acid (5%), minced, and homogenized. The homogenate was centrifuged (10,000 × g) at 4°C for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was used to determine lung GSH content as previously described (12,20).

Imaging studies

In vivo imaging studies described below were conducted on randomly selected subsets of rats from each exposure condition group. Sample sizes were chosen to achieve a power ≥ 85% using power analysis (ANOVA power) based on previously published means and standard deviations of the lung uptake of 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin (11–13).

99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin were constituted and labeled according to kit directions as previously described (11,12), while 99mTc-macroaggregated albumin (MAA) was obtained in its labeled form. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40–50 mg/kg, i.p.) and a femoral vein was cannulated. The rat was then placed supine on a plexiglass plate (4 mm) positioned directly on the face of a parallel-hole collimator (hole diameter = 2 mm, depth = 25 mm) attached to a modular gamma camera (Radiation Sensors, LLC) for planar imaging (11,12). An injection (37–74 MBq) of 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin was administered via the femoral vein catheter. Both agents reach steady-state in the lung by 20 minutes post-injection, at which time a one-minute planar image of 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin was acquired (11,12).

To investigate the role of the anti-oxidant GSH in the lung retention of 99mTc-HMPAO, a random subset of rats that were injected with 99mTc-HMPAO were then treated with DEM (1g/kg body wt i.p.) (12). DEM depletes GSH by conjugating with it to form a thioether conjugate via a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme glutathione-S-transferase (12). Forty-five minutes after DEM treatment and without relocation of the rat, a second injection of 99mTc-HMPAO was made and the animal reimaged 20 minutes later.

Then in all rats, a final injection of 99mTc-MAA (37 MBq) was made via the same femoral cannula and the rat re-imaged. The 99mTc-MAA injection provided a planar image in which the lung boundaries were clearly identified, since >95% of 99mTc-MAA lodged in the lungs. After imaging, the rats were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital. For a subset of the imaged rats, the lungs were removed, fixed inflated with paraformaldehyde, and then following 99mTc decay for 72 hrs (~12 half-lives), used for histological studies described above.

Image analysis

Images were analyzed using MATLAB-based software developed in-house. The boundaries of the upper portion of the lungs were identified in the high-sensitivity 99mTc-MAA images and manually outlined to construct a lung region of interest (ROI) free of liver contribution (12). The 99mTc-MAA lung ROI mask was then superimposed on the 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin images yielding a lung 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin ROI. No registration was required since the animal was maintained in the same location throughout the imaging study. Background regions in the upper forelimbs were also identified in the 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin images to normalize lung activity for injected 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin specific activity, dose, and decay (11,12). Mean counts/sec/pixel/injected dose within both the lung and forelimb-background ROIs were then determined and decay corrected. The ratio of the lung and background ROI signals averaged over the 15–20 minute time interval, when the 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin signal within the ROIs had reached steady state, was used as the measure of lung 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-duramycin uptake (11,12). 99mTc-HMPAO images acquired after DEM treatment were analyzed in the same way except that the pre-injection baseline activity level within each ROI was subtracted from the corresponding post-injection activity level to account for residual 99mTc-HMPAO from the first injection (12).

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation of data was carried out using SigmaPlot version 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Results are expressed as means ± SE unless stated otherwise. To evaluate differences between means of groups at different exposure times with the same treatment (hyperoxia, hyperoxia + DEM, hyperoxia + H2, or hyperoxia + H2 + DEM), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks was used. To evaluate differences pre and post DEM for a given group, a paired two-tailed t-test was used. To evaluate differences between hyperoxia and hyperoxia+H2 at a given exposure time, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used. For histology, scores of two graders were averaged, then performance of the groups compared by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks.

RESULTS

Body weights, lung wet weight, lung wet/dry weight ratios, and pleural effusion

Treatment with H2 had no effect on the hyperoxia-induced increase or decrease in body weight at 24 hr or 60 hrs (Table 2). However, the loss in body weight after 48 hrs of exposure was smaller (0.98±0.34%) with hyperoxia+H2 as compared to hyperoxia alone (2.12±0.32%).

Table 2.

Body weight (BW) pre- and post-treatment

| Groups (n) | Pre-BW (g) | Post-BW (g) | % change in BW |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-hr: hyperoxia (8) | 346 ± 3 | 350 ± 3 | 1.04 ± 0.73 |

| 24-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (7) | 347 ± 3 | 351 ± 3* (p = 0.047) | 1.33 ± 0.53 |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia (45) | 339 ± 4 | 332 ± 4* (p < 0.001) | −2.12 ± 0.32 |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (41) | 344 ± 5 | 341 ± 5* (p < 0.001) | −0.98 ± 0.34# (p = 0.018) |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia (24) | 344 ± 4 | 325 ± 4& (p < 0.001) | −5.36 ± 0.57 |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (14) | 340 ± 4 | 321 ± 4* (p < 0.001) | −5.52 ± 0.64 |

Different from corresponding pre-body weight (paired Student’s t-test),

different from corresponding pre-body weight (Wilcoxon Signed Rank test),

different from 48 hr hyperoxia (unpaired Student’s t-test).

n = number of rats.

Rat exposure to hyperoxia for 48 or 60 hrs increased left lobe wet weight/body weight ratio by 35% and 79%, respectively, as compared to that of normoxia rats (Table 3). Inclusion of H2 in the chamber gas mixture did not have a significant effect on this increase. The wet-to-dry weight ratio at 24 hrs was greater with hyperoxia+H2 than with hyperoxia alone, but not at 48 or 60 hrs.

Table 3.

Lung weights

| Group | Left lobe wet weight/body weight (mg/g) (n) | Left lobe wet/dry ratio (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | 1.23 ± 0.02 (18) | 5.36 ± 0.07 (18) |

| 24-hr: hyperoxia | 1.22 ± 0.05 (5) | 4.82 ± 0.07 (5) |

| 24-hr: hyperoxia + H2 | 1.30 ± 0.03 (4) | 5.31 ± 0.05# (4) (p = 0.001) |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia | 1.55 ± 0.07*(15) (p < 0.001) | 5.55 ± 0.08 (18) |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia + H2 | 1.45 ± 0.04* (22) (p < 0.001) | 5.55 ± 0.10 (23) |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia | 2.16 ± 0.09* (10) (p < 0.001) | 5.87 ± 0.24 (12) |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia + H2 | 2.22 ± 0.14* (12) (p < 0.001) | 6.14 ± 0.23* (12) (p = 0.014) |

Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks followed by Dunn’s test:

different from normoxia.

different from 24 hr hyperoxia (unpaired Student’s t-test).

n = number of rats.

No measurable pleural effusion was observed in any of the groups of rats except for 60-hr hyperoxia and 60-hr hyperoxia+H2. Table 4 shows that inclusion of H2 in the chamber gas mixture reduced by pleural effusion within the chest cavity at this time point.

Table 4.

Effect of H2 on injury endpoints

| Group | 3-NT (n) | 4-HNE (n) | Pleural effusion (g) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | 1.0 ± 0.332 (6) | 1.0 ± 0.34 (6) | NG |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia | 3.21 ± 0.75* (6) (p = 0.023) | 1.52 ± 0.47 (6) | NG |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia + H2 | 3.07 ± 0.77* (6) (p = 0.041) | 0.94 ± 0.28 (6) | NG |

| Normoxia | 1.0 ± 0.113 (6) | 1.0 ± 0.15 (6) | NG |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia | 8.87 ± 1.68* (6) (p = 0.002) | 1.48 ± 0.30 (6) | 9.3 ± 0.6 (17) |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia + H2 | 4.25 ± 0.78*# (6) * (p = 0.002) # (p = 0.032) |

1.62 ± 0.42 (6) | 2.9 ± 0.6# (15) (p < 0.001) |

3-NT and 4-HNE band density normalized to β actin and resulting values normalized to normoxia.

NG = negligible.

Unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test:

different from normoxia,

different from 60-hr hyperoxia.

n = number of rats.

Indices of oxidative stress

Table 4 shows that expression of 3-NT, as an indicator of oxidative stress, was elevated following 60 hr of exposure to hyperoxia alone. This increase was reduced by 50% in the animals exposed to hyperoxia+H2. The expression of another indicator of oxidative stress (4-HNE) was not elevated following rat exposure to hyperoxia or hyperoxia+H2.

Histology

Images of representative lung sections stained with H&E appear in Figure 1. Lung histology from rats exposed to hyperoxia for 24 or 48 hrs was indistinguishable from normoxia rats including scores for neutrophilic influx, edema or thickness of the diffusion barrier (Table 5; 48 hrs data not shown). Samples from lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia for 60 hrs exhibited variable degrees of edema, neutrophilic influx and, by high power, an increase in the width of the alveolar septum (diffusion barrier) relative to controls. Samples from rats exposed to hyperoxia+H2 for 60 hrs were not different from those of normoxia rats and were different from hyperoxia alone with respect to neutrophilic influx and barrier thickness. These data support protection by H2 relative to injury of rats exposed to 60-hrs hyperoxia alone.

Figure 1.

H&E lung slices from a normoxia rat, and from rats exposed to hyperoxia for 48 hrs and 60 hrs or to hyperoxia+ H2 for 60 hrs. Top panels are at lower power than lower panels to facilitate assessment of neutrophilic influx and edema. Higher power images were used to assess thickness of the alveolar septum.

Table 5.

H&E inflammation scores

| Group (n) | Neutrophils | Edema | Thickness diffusion barrier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia (4) | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia (5) | 1.40 ± 0.16* (p <0.001) | 0.33 ± 0.19 | 1.09 ± 0.09* (p <0.001) |

| 60-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (4) | 0.08 ± 0.08# (p <0.001) | 0 ± 0 | 0.25 ± 0.13# (p <0.001) |

Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks followed by Dunn’s test:

different from normoxia,

different from hyperoxia.

n = number of rats.

BAL protein and cell counts

Protein concentration in BAL was greater, compared to normoxic controls, in 48-hr hyperoxia (150%) and 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 (63%) rats (Table 6). Total cell count in BAL was higher in 48-hr hyperoxia rats than in hyperoxia+H2 rats (Table 6).

Table 6.

BAL protein and cell counts

| Group (n) | Protein (mg/ml) | Cell count (x 104) in collected BAL fluid |

|---|---|---|

| Normoxia (6) | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 91 ± 22 |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia (5) | 1.82 ± 0.36* (p = 0.009) | 76 ± 5 |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (6) | 1.19 ± 0.15* (p = 0.041) | 48 ± 5*

# * (p = 0.041), # (p = 0.005) |

Unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test:

different from normoxia,

different from hyperoxia.

n = number of rats.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

We quantified ADP-stimulated depolarization of ΔΨm in mitochondria isolated from normoxia, hyperoxia, and hyperoxia+H2 rat lungs using R123. Figure 2 shows that in the presence of mitochondria and pyruvate + malate (complex I substrates), the addition of ADP (state 3) stimulated a transient and reversible efflux of R123 from mitochondria, consistent with transient and reversible partial depolarization of ΔΨm (19). Addition of the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP depolarized ΔΨm resulting in the maximal efflux of R123 from mitochondria (19,21). Similar results were obtained with succinate (complex II substrate) as substrate. One measure of the kinetics of ADP-stimulated ΔΨm depolarization and repolarization is the full width at half maximum time (FWHM) for R123 return to baseline (state 4), see Figure 2. Table 7 shows that rat exposure to hyperoxia for 48 hrs increased FWHM time by ~50%. This suggests that ΔΨm recovery from ADP-induced depolarization in mitochondria from hyperoxia lungs was substantially slower than that in normoxia lungs, consistent with decreases in complex I and II activities in lungs of hyperoxia rats (22). Table 7 shows that the ΔΨm recovery time (FWHM) from ADP-stimulated depolarization, which increased with hyperoxia, partially reversed with hyperoxia+H2, consistent with the ability of H2 to protect mitochondria from functional degradation by hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

Averaged R123 emission signal in mitochondria isolated from lungs of normoxia, 48-hr hyperoxia, and 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 rats. FWHM = full width, half maximum.

Table 7.

Δψm recovery time from ADP-stimulated depolarization

| Group | FWHM (min) Pyruvate +Malate (n) | FWHM (min) Succinate (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | 1.98 ± 0.18 (7) | 1.75± 0.16 (6) |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia | 3.30 ± 0.29* (6) (p = 0.002) | 2.79 ± 0.34* (7) (p = 0.036) |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia +H2 | 2.45 ± 0.26 (6) | 1.78 ± 0.20 (6) |

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm).

FWHM = Full width at half maximum for 100 mM ADP-stimulated depolarization of Δψm.

Unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test:

different from normoxia,

n = number of rats.

Imaging results

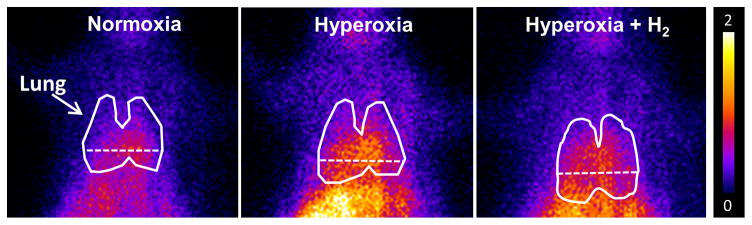

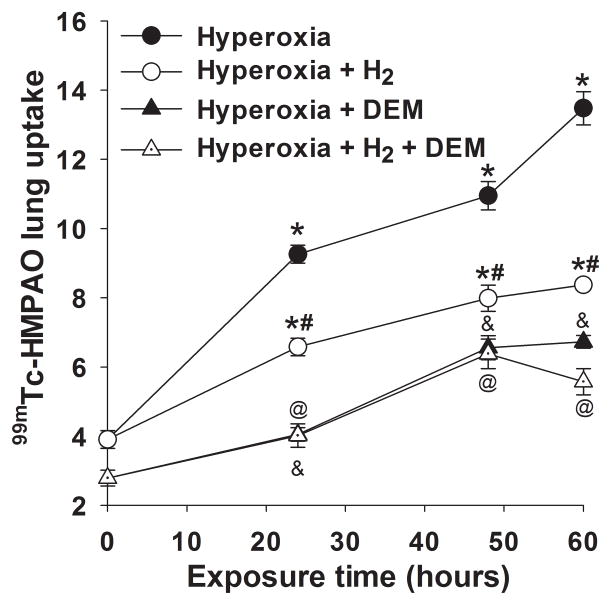

Lung uptake of 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin was quantified from the biomarker images in groups of normoxia and hyperoxia rats with and without H2. Figure 3 shows representative 99mTc-HMPAO images obtained at steady-state from a normoxia rat (left), and from rats 48 hrs after exposure to either hyperoxia (middle), or hyperoxia+H2 (right), where the lung ROI is outlined. The images show enhanced 99mTc-HMPAO uptake in the lungs of the hyperoxia rat, which is reduced in the hyperoxia+H2 rat. Figure 4 shows lung uptake (the ratio of lung-to-background signal at steady-state) of 99mTc-HMPAO over 60 hrs of exposure to hyperoxia (filled circles) or hyperoxia+H2 (open circles). 99mTc-HMPAO uptake increased in a time-dependent manner, reaching a maximum increase of ~270% at 60 hr. At each time point, inclusion of H2 in the chamber gas mixture significantly reduced 99mTc-HMPAO uptake; at 60-hr of exposure uptake was reduced to ~120% of that of normoxia rats. For a given treatment (hyperoxia, hyperoxia +H2), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test was used to evaluate differences between means of groups at the four exposure times. Unpaired t-tests were used to evaluate differences between hyperoxia and hyperoxia+H2 at each time point.

Figure 3.

Representative planar images of 99mTc-HMPAO distribution in a normoxia (left), 48-hr hyperoxia (center) and 48-hr hyperoxia + H2 (right) rat 20 min following injection. Lung ROI is determined from the 99mTc-MAA image with the dashed horizontal lower boundary to avoid liver contribution.

Figure 4.

Lung uptake of 99mTc-HMPAO in rats exposed to hyperoxia (filled circles) or hyperoxia+H2 (open circles) for 24, 48 or 60 hrs. *different from normoxia (time = 0), #different from hyperoxia alone, &different from hyperoxia pre DEM, @different from hyperoxia+H2 pre DEM, all with p < 0.001. (n) = number of rats: normoxia (7), normoxia + DEM (7), 24-hr hyperoxia (5), 24-hr hyperoxia + DEM (5), 24-hr hyperoxia+H2 (7), 24-hr hyperoxia + H2 + DEM (7), 48-hr hyperoxia (5), 48-hr hyperoxia +DEM (5), 48-hr hyperoxia +H2 (8), 48-hr hyperoxia + H2 + DEM (5), 60-hr hyperoxia (6), 60-hr hyperoxia + DEM (5), 60-hr hyperoxia+H2 (4), 60-hr hyperoxia + H2 + DEM (4).

We investigated the role of GSH in 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake by imaging rats before and after treatment with DEM (12). DEM treatment resulted in significantly reduced uptake in both the hyperoxia (Figure 4, filled circles versus filled triangles) and hyperoxia+H2 groups (open circles versus open triangles), suggesting the role of GSH in the uptake of 99mTc-HMPAO. The reduction in 99mTc-HMPAO uptake in hyperoxia (50%) and hyperoxia+H2 (33%) rats was a greater fraction than that of normoxia rats (24%) (Figure 4). For rats exposed to hyperoxia or hyperoxia+H2 for 24 hrs, the enhanced 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake was mostly DEM-sensitive. On the other hand, for rats exposed to hyperoxia or hyperoxia+H2 for 48 and 60 hr, only ~50% of the measured increase in 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake was DEM-sensitive. For a given treatment (hyperoxia + DEM, hyperoxia + H2 + DEM), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test was used to evaluate differences between means of groups at the four exposure times. A paired t-test was used to evaluate differences pre and post DEM for a given group. For a given exposure time, an unpaired t-test was used to evaluate differences between hyperoxia and hyperoxia+H2.

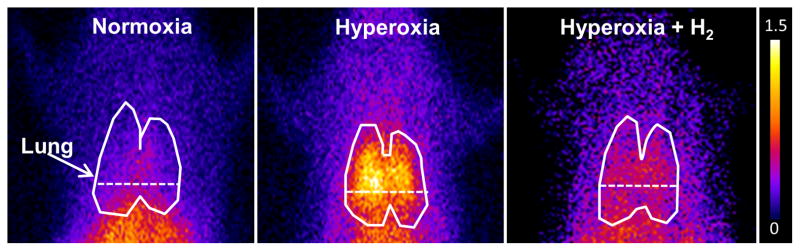

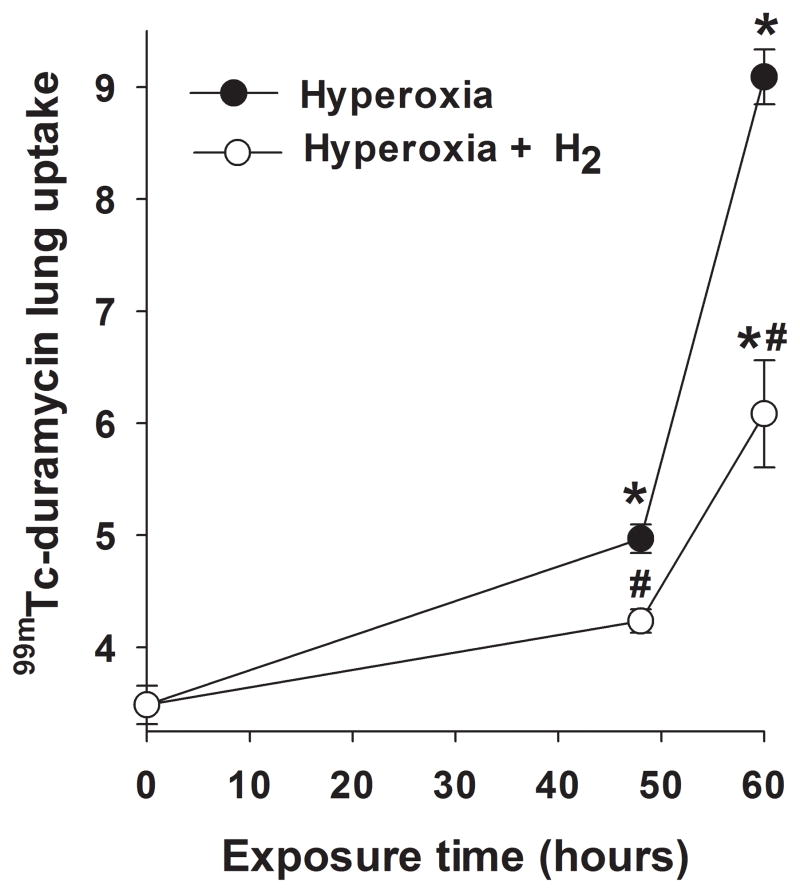

Figure 5 shows representative 99mTc-duramycin images at steady-state obtained from a normoxia rat (left), and from rats 60 hrs after exposure to either hyperoxia (middle), or hyperoxia+H2 (right). The enhanced 99mTc-durmaycin uptake evident in the hyperoxia rat appears reduced in the hyperoxia+H2 rat. Figure 6 shows the time course of 99mTc-duramycin uptake in lungs of rats exposed to either hyperoxia (filled circles) or hyperoxia+H2 (open circles). The time-dependent increase in 99mTc-duramycin lung uptake reported previously with hyperoxia was reduced from ~150% at 60 hrs of exposure (11) to ~70% increase when H2 was included in the chamber gas mixture. For a given treatment (hyperoxia, hyperoxia +H2), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s range test was used to evaluate differences between means of groups at the three exposure times. For a given exposure time, an unpaired t-test was used to evaluate differences between hyperoxia and hyperoxia+H2.

Figure 5.

Representative planar images of 99mTc-duramycin distribution in a normoxia (left), 60-hr hyperoxia (center) and 60-hr hyperoxia+H2 (right) rat 20 min following injection. Lung ROI is determined from the 99mTc-MAA image with the dashed horizontal lower boundary to avoid liver contribution.

Figure 6.

Lung uptake of 99mTc-duramycin in rats exposed to hyperoxia (filled circles) or hyperoxia+H2 (open circles) for 48 or 60 hrs. *different from normoxia (time 0) with p < 0.001, #different from hyperoxia alone with p = 0.001 for 48 hrs and p < 0.001 for 60 hrs. (n) = number of rats: normoxia (9), 48-hr hyperoxia (7), 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 (6), 60-hr hyperoxia (7), 60-hr hyperoxia+H2 (5).

Lung GSH content

Table 8 shows the results of the glutathione assays indicating that rat exposure to hyperoxia increased lung tissue GSH content after 48 hrs (36%) of exposure as compared to lungs of normoxia rats. Rat exposure to hyperoxia+H2 for 48 hrs reduced that increase by 42%. Figure 7 suggests a strong relationship between GSH tissue content measured from lung tissue assays and in vivo 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake determined from imaging (12).

Table 8.

Glutathione (GSH) content of lung homogenate

| Group (n) | GSH (fraction of normoxia) |

|---|---|

| Normoxia (7) | 1.00 ± 0.08 |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia (7) | 1.36 ± 0.02* * (p <0.001) |

| 48-hr: hyperoxia + H2 (6) | 1.21 ± 0.03*

# * (p <0.001) # (p <0.001) |

Unpaired Student’s t-test:

different from normoxia,

different from hyperoxia.

n = number of rats.

GSH concentration for normoxia lungs was 9.02 ± 0.38 (n = 7) μmol/g dry wt.

Figure 7.

Relationship between 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake (Figure 4) and lung tissue GSH content (as fraction of normoxia, Table 8).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The present study detects and tracks the anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic properties of H2 therapy in vivo and to demonstrate protection after as early as 24 hrs of hyperoxia exposure. The results demonstrate the ability of the two molecular biomarkers 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin to quantify lung injury and the response to H2 treatment in vivo in rats exposed to hyperoxia as a model of human ALI/ARDS. Smaller increases in the lung uptake of both 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-duramycin over the 60-hr exposure period were observed in rats exposed to hyperoxia+H2 as compared to rats exposed to hyperoxia alone. These results are consistent with the anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties of H2 (5–9). They are also in agreement with our observations of decreased injury severity in H2 treated rats based on lung histology and lavage constituents, pleural effusion, and less mitochondrial dysfunction as identified by kinetic responses of isolated mitochondria.

99mTc-HMPAO was originally developed as a brain perfusion agent but its uptake and retention in several tissues serve as a marker of tissue redox state (23). 99mTc-HMPAO reduction and thus its cellular retention, has been shown to be strongly dependent on the oxidoreductive state of the tissue including intracellular GSH content and other factors involving mitochondrial redox state (12). Recently, we demonstrated a strong correlation between 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake and lung tissue GSH content (12). The results of the current study (Figure 4) show that 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake increased steadily over the 60-hr hyperoxia exposure period, and that most of the increase was DEM-inhibitable or GSH-dependent, consistent with lung tissue response to hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress.

On the other hand, exposure to hyperoxia+H2 decreased 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake in comparison to lung uptake in rats exposed to hyperoxia alone, and most of the decrease was in the GSH-dependent component. Since antioxidants such as GSH increase in response to oxidative stress, the effect of H2 on the DEM-sensitive portion of 99mTc-HMPAO lung uptake and on the GSH content of lung homogenate suggests that H2 treatment reduced hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress. This is reflective of H2’s anti-oxidant properties and consistent with its ability to mitigate the hyperoxia-induced increase in 3-NT expression in our studies (Table 4). Sun et al. (9) showed that rat exposure to hyperoxia for 60 hrs increased lung tissue superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity compared to that of normoxia rats, and that the increased SOD activity was smaller in lungs of hyperoxia-exposed rat that received multiple intraperitoneal injections of H2-rich saline during the exposure period. In that study, the anti-oxidant properties of H2 were reflected by its ability to mitigate hyperoxia-induced increase in lung tissue lipid and DNA oxidation (Table 9). Kawamura et al. suggested that the H2 protective effect is via the induction of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) signaling pathway (5). They showed that the expressions of Nrf2-ARE dependent enzymes, including heme oxygenase (HO-1), increased more in lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia+H2 for 60 hrs than in lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia alone (5). HO-1 is important for removing free heme, a source of iron which plays a key role in hydroxyl radical formation via the Fenton reaction (5). Although the exact mechanism by which H2 exerts its anti-oxidant properties is still not fully understood, the results of current and previous studies suggest that the mechanism could be either by directly scavenging hydroxyl radical via an exothermic reaction (8) and/or indirectly by its effect on the expression of HO-1 (5).

Table 9.

Summary of effects of rat exposure to hyperoxia + H2 for 60 hrs compared to exposure to hyperoxia alone for 60 hrs on various antioxidant enzymes and indices of lung injury

| Kawamura et al. 2013 | Sun et al. 2011 | Current study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat strain | Adult Lewis (male) | Adult SD (male) | Adult SD (male) |

| H2 delivery | 2% H2 gas (inhaled) | Saline-rich H2 (i.p.) | 2% H2 gas (inhaled) |

| Body weight loss | Lower | NA | NS |

| Lung wet weight | NA | NA | NS |

| Lung wet/dry | −8% | −7% | +5% |

| Pleural effusion | −40% | −30% | −70% |

| SOD | NA | −40% | NA |

| 3-NT | NA | NA | −51% |

| 4-HNE | NA | NA | NS |

| BAL protein | −46% | NA | NA |

| H&E score | Lower | Lower | Lower |

| Apoptosis | −31% | −33% | −53% |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | Lower | Lower | NA |

| MDA | NA | −40% | NA |

| 8-OHdG | NA | −49% | NA |

| HO-1 expression | +136% | NA | NA |

| NQO1 expression | +93% | NA | NA |

| GSTA2 expression | +158% | NA | NA |

| Prdx1 expression | +105% | NA | NA |

NA: not available, NS: not significant. GSTA2 = glutathione S-transferase A2; Prdx1= peroxiredoxin 1; MDA = malondialdehyde; 8-OHdG = 8-hydroxy-2′ –deoxyguanosine; SOD = superoxide dismutase

The increase in GSH content of lung homogenate (+36% for 48-hr hyperoxia and +21% for 48-hr hyperoxia+H2 compared to normoxia) is lower than the ~100–170% increase in HMPAO lung uptake measured from the in vivo images and the ~50–280% increase in the DEM-sensitive portion of the HMPAO lung uptake. One explanation for this difference could be the fact that the GSH content reported in this study is the average GSH content of all lung cells and alveolar fluid. Although the results of this study do not provide information regarding the specific types of lung cells contributing to the lung uptake and retention of HMPAO, previous studies have suggested that its retention is predominantly attributable to endothelial cells (24,25), which account for ~50% of lung cells and are in direct contact with blood (4). Other studies have also demonstrated that different cell types have different GSH content, and oxidant stress has different effects on the GSH content of these cells (26,27). For instance, Deneke et al. demonstrated that exposure of endothelial cells to hyperoxia (85% O2 for 48 hours) increased GSH content by 85% (26). On the other hand, neutrophil GSH content is not sensitive to oxidant injury (27). Thus, depending on the GSH content of the various lung cells and how the GSH content of these cells change in response to exposure to hyperoxia, the GSH content in lung homogenate measured in this study may overestimate or underestimate the effect of hyperoxia or hyperoxia+H2 on GSH content of pulmonary capillary endothelial cells.

99mTc-duramycin serves as a molecular probe that binds to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), which has little presence on the surface of normal viable cells, but becomes exposed onto the cell surface and/or accessible to the extracellular milieu with apoptosis and necrosis, respectively (11,28). Previously we reported an increase in the lung uptake of 99mTc-duramycin in rats exposed to hyperoxia or radiation, and demonstrated a strong correlation between 99mTc-duramycin lung uptake and cleaved caspase 3 positive cells, predominantly endothelial cells (11,14). Figure 6 shows that 99mTc-duramycin lung uptake was significantly lower in lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia+H2 as compared to that in lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia alone (11), reflective of the anti-apoptotic properties of H2 (5,8,9). This result is consistent with those reported by others (Table 9). For instance, Sun et al. reported that H2 treatment mitigated hyperoxia-induced increases in TUNEL positive lung cells (9). Kawamura et al. (5) demonstrated the ability of H2 to protect against hyperoxia-induced increases in the number of caspase 3 positive lung cells. Additional results show that H2 inhibited hyperoxia-induced increases in the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and decreases in the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax (5). Dixon et al. suggested that H2’s anti-apoptotic effect is via its ability to inhibit the activation of caspase-3 (8).

The anti-inflammation properties of H2 are reflected in the histological (Figure 1) and BAL (Table 6) results, which show less cellular infiltration in lungs of rats exposed to hyperoxia+H2 compared to those exposed to hyperoxia. These results are consistent with other studies (Table 9) that demonstrated the ability of H2 to mitigate hyperoxia-induced increases in BAL protein, histology, and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lung tissue (5,9).

Isolated mitochondria studies using R123 (Figure 2, Table 7) suggest the ability of H2 to provide mitochondrial electron transport chain with partial protection from hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress. We previously demonstrated significant decreases in complex I and II activities in lung of rats exposed to hyperoxia for 48 hrs (22). Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is highly sensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS) (29). A hyperoxia-induced increase in the rate of ROS formation could damage mtDNA and as a result compromise complex I activity since 7 of 45 subunits of complex I are encoded by mtDNA (29,30). This increase in ROS formation could also cause direct alteration to complex I activity by oxidizing the key phospholipid cardiolipin, which is sensitive to ROS (31,32). Oxidation of cardiolipin could lead to an increase in the loss of electrons at complex I and in the rate of mitochondrial superoxide formation at complex I (31,32). Furthermore, cardiolipin oxidation can affect complex II since it is required for its optimal activity and stability (33). Our results (Figure 2, Table 7) using R123 suggest that H2 partially protected complex I and II activities from oxidative stress.

In the present study, the effect of H2 on hyperoxia-induced body weight loss and increase in lung wet/dry weight ratio after 60 hrs of exposure (Tables 2–3) are not consistent with those reported by other studies (Table 9). For instance, both Sun et al. and Kawamura et al. reported lower lung wet/dry weight ratios in rats treated with hyperoxia+H2 as compared to rats treated with hyperoxia (5,9). In addition, Kawamura et al. reported that H2 reduced rat body weight loss after 60 hrs of exposure to hyperoxia (5). The difference between these results and results of the current study could be due to differences in rat strains (Sprague-Dawley vs. Lewis rats in Kawamura et al. (5)) or in H2 administration (intraperitoneal injection of H2-rich saline in Sun et al. (9)). Xie et al. showed that the protective effects of H2 against sepsis-induced lung injury is dose dependent over 1–4 % range (10). Thus, additional protection might be observed in Sprague-Dawley rats with higher concentrations of H2 than the 2% used in the present study.

Several gaseous therapies have been evaluated for hyperoxia-induced ALI/ARDS, including nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), and H2 (8,34,35). Like NO and CO, H2 is highly permeable across various cellular barriers and hence capable of accessing key cellular compartments such as mitochondrion which appear to play a key role in the pathogenesis of human ALI/ARDS. However, H2 is advantageous since it does not affect the physiological or immune response of key ROS (superoxide and hydrogen peroxide). Moreover, H2 is not toxic at high concentrations and is safe at concentrations < 4.1% when mixed with O2 (8).

In conclusion, the results suggest the potential translational utility of imaging with two SPECT biomarkers, one of which is already in clinical use, for in vivo assessment of key cellular pathways involved in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS and for monitoring responses to potential therapies such as inhaled H2 gas.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants 1R15HL129209 (Audi, Clough, Jacobs), 1R01HL116530 (Jacobs, Audi, Clough), and 5R01CA185214 (Ming Zhao), VA Merit Review Award BX001681 (Jacobs, Audi, Clough), and the Alvin and Marion Birnschein Foundation (Audi, Clough).

We thank Ying Gao and Jayashree Narayanan for their help with tissue assays, and Dr. Raphael Fraser for his assistance with the statistical review.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. Jama. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay MA, Zemans RL. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:147–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, Donati A, Rinaldi L, Marudi A, Morelli A, Antonelli M, Singer M. Effect of Conservative vs Conventional Oxygen Therapy on Mortality Among Patients in an Intensive Care Unit: The Oxygen-ICU Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2016;316:1583–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crapo JD, Barry BE, Foscue HA, Shelburne J. Structural and biochemical changes in rat lungs occurring during exposures to lethal and adaptive doses of oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:123–43. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawamura T, Wakabayashi N, Shigemura N, Huang CS, Masutani K, Tanaka Y, Noda K, Peng X, Takahashi T, Billiar TR, Okumura M, Toyoda Y, Kensler TW, Nakao A. Hydrogen gas reduces hyperoxic lung injury via the Nrf2 pathway in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L646–56. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00164.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta S. Molecular hydrogen is a novel antioxidant to efficiently reduce oxidative stress with potential for the improvement of mitochondrial diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:586–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, Watanabe M, Nishimaki K, Yamagata K, Katsura K, Katayama Y, Asoh S, Ohta S. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med. 2007;13:688–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon BJ, Tang J, Zhang JH. The evolution of molecular hydrogen: a noteworthy potential therapy with clinical significance. Med Gas Res. 2013;3:10. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Q, Cai J, Liu S, Liu Y, Xu W, Tao H, Sun X. Hydrogen-rich saline provides protection against hyperoxic lung injury. J Surg Res. 2011;165:e43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie K, Yu Y, Huang Y, Zheng L, Li J, Chen H, Han H, Hou L, Gong G, Wang G. Molecular hydrogen ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice through reducing inflammation and apoptosis. Shock. 2012;37:548–55. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31824ddc81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audi SH, Jacobs ER, Zhao M, Roerig DL, Haworth ST, Clough AV. In vivo detection of hyperoxia-induced pulmonary endothelial cell death using (99m)Tc-duramycin. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Audi SH, Clough AV, Haworth ST, Medhora M, Ranji M, Densmore JC, Jacobs ER. 99MTc-Hexamethylpropyleneamine Oxime Imaging for Early Detection of Acute Lung Injury in Rats Exposed to Hyperoxia or Lipopolysaccharide Treatment. Shock. 2016;46:420–30. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clough AV, Audi SH, Haworth ST, Roerig DL. Differential lung uptake of 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime and 99mTc-duramycin in the chronic hyperoxia rat model. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1984–1991. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.108498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medhora M, Haworth S, Liu Y, Narayanan J, Gao F, Zhao M, Audi S, Jacobs ER, Fish BL, Clough AV. Biomarkers for Radiation Pneumonitis Using Noninvasive Molecular Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1296–301. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.160291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, Kuebler WM. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:725–738. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Densmore JC, Jeziorczak PM, Clough AV, Pritchard KA, Jr, Cummens B, Medhora M, Rao A, Jacobs ER. Rattus model utilizing selective pulmonary ischemia induces bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Shock. 2013;39:271–7. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318281a58c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirker A, Murdoc CE, Protti A, Sawyer GJ, Santos CX, Martin D, Zhang X, Brewer AC, Zhang M, Shah AM. Cell-specific effects of Nox2 on the acute and chronic response to myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;98:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith IJ, Godinez GL, Singh BK, McCaughey KM, Alcantara RR, Gururaja T, Ho MS, Nguyen HN, Friera AM, White KA, McLaughlin JR, Hansen D, Romero JM, Baltgalvis KA, Claypool MD, Li W, Lang W, Yam GC, Gelman MS, Ding R, Yung SL, Creger DP, Chen Y, Singh R, Smuder AJ, Wiggs MP, Kwon OS, Sollanek KJ, Powers SK, Masuda ES, Taylor VC, Payan DG, Kinoshita T, Kinsella TM. Inhibition of Janus kinase signaling during controlled mechanical ventilation prevents ventilation-induced diaphragm dysfunction. FASEB J. 2014;28:2790–803. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang M, Camara AK, Stowe DF, Qi F, Beard DA. Mitochondrial inner membrane electrophysiology assessed by rhodamine-123 transport and fluorescence. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:1276–85. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Audi SH, Roerig DL, Haworth ST, Clough AV. Role of glutathione in lung retention of 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime in two unique rat Models of hyperoxic lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:658–65. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00441.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan Z, Audi SH, Bongard RD, Gauthier KM, Merker MP. Quantifying mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials in intact pulmonary arterial endothelial cells based on extracellular disposition of rhodamine dyes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L762–72. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00334.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sepehr R, Audi SH, Staniszewski KS, Haworth ST, Jacobs ER, Ranji M. Novel Flurometric Tool to Assess Mitochondrial Redox State of Isolated Perfused Rat Lungs after Exposure to Hyperoxia. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2013;1 doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2013.2285916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neirinckx RD, Burke JF, Harrison RC, Forster AM, Andersen AR, Lassen NA. The retention mechanism of technetium-99m-HM-PAO: intracellular reaction with glutathione. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:S4–12. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo SJ, Yang KT, Chen DR. Objective and noninvasive detection of sub-clinical lung injury in breast cancer patients after radiotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:954–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suga K, Uchisako H, Nishigauchi K, Shimizu K, Kume N, Yamada N, Nakanishi T. Technetium-99m-HMPAO as a marker of chemical and irradiation lung injury: experimental and clinical investigations. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1520–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deneke SM, Steiger V, Fanburg BL. Effect of hyperoxia on glutathione levels and glutamic acid uptake in endothelial cells. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:1966–71. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.5.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durak H, Kilinc O, Ertay T, Ucan ES, Kargi A, Kaya GC, Sis B. Tc-99m-HMPAO uptake by bronchoalveolar cells. Ann Nucl Med. 2003;17:107–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02988447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao M, Li Z, Bugenhagen S. 99mTc-labeled duramycin as a novel phosphatidylethanolamine-binding molecular probe. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1345–52. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruchko M, Gorodnya O, LeDoux SP, Alexeyev MF, Al-Mehdi AB, Gillespie MN. Mitochondrial DNA damage triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in oxidant-challenged lung endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L530–5. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00255.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swalwell H, Kirby DM, Blakely EL, Mitchell A, Salemi R, Sugiana C, Compton AG, Tucker EJ, Ke BX, Lamont PJ, Turnbull DM, McFarland R, Taylor RW, Thorburn DR. Respiratory chain complex I deficiency caused by mitochondrial DNA mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:769–75. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Pistolese M, Ruggiero FM. Reactive oxygen species affect mitochondrial electron transport complex I activity through oxidative cardiolipin damage. Gene. 2002;286:135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chicco AJ, Sparagna GC. Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C33–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00243.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwall CT, Greenwood VL, Alder NN. The stability and activity of respiratory complex II is cardiolipin-dependent. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1817:1588–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otterbein LE, Mantell LL, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide provides protection against hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L688–94. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelin LD, Welty SE, Morrisey JF, Gotuaco C, Dawson CA. Nitric oxide increases the survival of rats with a high oxygen exposure. Pediatr Res. 1988;43:727–32. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]