Abstract

The transitional stage of B-cell development is a formative stage in the spleen where autoreactive specificities are censored as B cells gain immune-competence, but the intrinsic and extrinsic factors regulating survival of transitional stage 1 (T1) B cells are unknown. We report that B-cell expression of IFNβ is required for optimal survival and TLR7 responses of transitional B cells in the spleen and was over-expressed in T1 B cells from BXD2 lupus-prone mice. Single-cell gene expression analysis of B6 Ifnb+/+ vs. B6 Ifnb−/− T1 B cells revealed heterogeneous expression of Ifnb in WT B cells and distinct gene expression patterns associated with endogenous IFNβ. Single cell analysis of BXD2 T1 B cells revealed that Ifnb is expressed in early T1 B-cell development with subsequent upregulation of Tlr7 and Ifna1. Together these data suggest that T1 B-cell expression of IFNβ plays a key role in regulating responsiveness to external factors.

Introduction

The survival responses of transitional B cells play a key role in shaping the development of mature, antibody producing B cells. Transitional stage 1 (T1) B cells are the initial immigrants in the spleen and are highly susceptible to negative selection following strong BCR ligand engagement (1, 2). T1 B cells that survive this negative selection become T2 or mature B cells that are competent to respond to immune challenges (3). Failures in this selection checkpoint are associated with aberrant activation and development of polyreactive self-antigen-reactive mature B cells in systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) and the development of anti-nuclear autoantibodies (4). The intrinsic and extrinsic factors that regulate the abnormal survival responses of T1 B cells in SLE are poorly understood.

Most studies into the differential survival responses of transitional B cells, both in normal B cell development and in autoimmunity, have focused on the interactions between cell surface Ag receptors and co-stimulatory molecules as well as the role of factors present in the extracellular environment, in particular IFNα and TLR ligands (5). The responsiveness of B cells to IFNβ has been less well studied compared to IFNα, although it has been shown that IFNβ has a higher affinity for IFNARs than IFNα (6, 7). It has been proposed that IFNβ acts as an initial signal that potentiates subsequent signaling by other type I IFNs and cytokines (8), and a role for IFNβ in the promotion of TLR signaling has been demonstrated (9, 10).

Here, we report a mechanistic model in which endogenous expression of IFNβ is central to the survival responses of new immigrant T1 B cells. Endogenous IFNβ is an important regulator of TLR7 responses during T1 B cell development and promotes their development into immune-competent B cells (3).

Materials and Methods

Mice

Ifnb deficient C57BL/6J mice were provided by Dr. Eleanor Fish, University of Toronto, Canada (11). Rag1 deficient and B6 Cd45.1 and Cd45.2 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. BXD2 GFP mice were generated by crossing of BXD2 mice with B6 GFP mice for >15 generations.

BM transplantation

BM cells (1 × 107) from the indicated donors were transferred or mixed at a 1:1 ratio of Cd45.1 B6 : Cd45.2 B6-Ifnb−/− or a 1:1:1 ratio of Cd45.1 B6 : Cd45.2 B6-Ifnb−/− : GFP+ BXD2 and injected i.v. into recipient mice as previously described (12).

In vitro stimulation and type I interferon neutralization

Purified B cells were stimulated with mouse IFNα or IFNβ (gift from Dr. Vithal Ghanta, CytImmune), 2 μg/mL TLR7 agonist CL264 (Invivogen) or CL264 + a polyclonal anti-mouse IgM (1 μg/mL, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or non-specific rat-IgG isotype control. For specific neutralization of type I IFNs, cells were pre-incubated with 50 μg/mL anti-IFNAR (clone MAR1-5A3, BioXCell) or 500 IU/mL anti-IFNβ (Rabbit IgG, Protein A purified, PBL Assay Science).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR reactions were carried out as described previously (12).

Single cell qRT-PCR

For single cell analyses, single T1 B cells were obtained from the spleens of CD45.1 B6 : CD45.2 B6 Ifnb−/− BM chimeras or 4 mo old female BXD2 mice. Analyses were performed using the BioMark Real-Time quantitative PCR (qPCR) system (Fluidigm Co., South San Francisco, CA) using the standard Fluidigm protocols. Primer sets amplifying the mRNAs of the relevant genes are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The averaged CT values were calculated from the system software [BioMark Real-Time PCR (polymerase chain reaction) Analysis, Fluidigm]. Gene expression values were calculated using the 2‒ΔCT value. Briefly, the CT value of each gene in each cell obtained from the BioMark system was normalized with the CT value of Gapdh (ΔCT) of each cell, and this was further converted to 2‒ΔCT to show the expression value of each gene. The 2‒ΔCT values were transferred to the ClustVis online web tool for hierarchical clustering analysis (13). ClustVis uses the heatmap feature available from the R package (version 0.7.7) for plotting the values as a heatmap. Expression levels of all genes were auto-scaled to provide all the genes equal weight in the classification algorithms. Missing data in the BioMark system were assigned a Ct of 999 by the instrument software and were removed. Since high CTs in the BioMark 96 × 96 microfluidic card were expected to be false positives due to baseline drift or formation of aberrant products, and since a sample with a single template molecule is expected to generate a lower CT, CT values that were larger than a cutoff of 25 were also removed (14). Cells not expressing the Gapdh housekeeping gene, or expressing it at extremely low values (Ct >35), were removed from the analysis, on the assumption that these cells were dead or damaged during the preparation process.

Data used for the Ifnb−/− versus WT T1 B cell clustering analysis can be obtained at http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/?s=KXZgiafggsgiqXF. Data used for the BXD2 T1 B cell clustering analysis can be obtained at http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/?s=ngDyEqjWVFxljgb (for the Ifna vs Ifnb dataset), http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/?s=GGGWfDLltagktnA (for the Cd93 vs Cd23 dataset), http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/?s=jBXpSUfvIiPfBeF (for the Cd93, Cd23, Ifnb, and Ifna7 dataset)

Flow cytometry

The following anti-mouse antibodies were used: BioLegend Pacific Blue–α-B220 (RA3-6B2), BV510-α-CD23 (B3B4), FITC-α-CD21/35 (7E9), PE-α-IFNAR1 (MAR1-5A3), PE-α-BAFFR (7H22-E16), Pacific Blue-α-CD45.1 (A20), AF647-α-CD45.2 (104); BD Bioscience BV650-α-CD93 (AA4.1), BV510-α-IgD (11-26c.2a); eBioscience PE-α-CD69 (H1.2F3), PECy7-α-IgM (eB121-15F9), APC-α-CD317 (PDCA1, eBio129c); PBL Assay Science FITC-α-IFNβ (RMMB-1). All FACS analyses included dead cell exclusion using fixable viability dye eFluor780 (eBioscience). La13–27 tetramer staining was carried out as previously described (15). Intracellular staining and flow cytometry analysis was carried out as previously described (12).

Histology

Frozen sections and analysis was carried out as previously described (12).

Statistics

Results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) or mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

Endogenous interferon-β regulates survival and development of transitional B cells

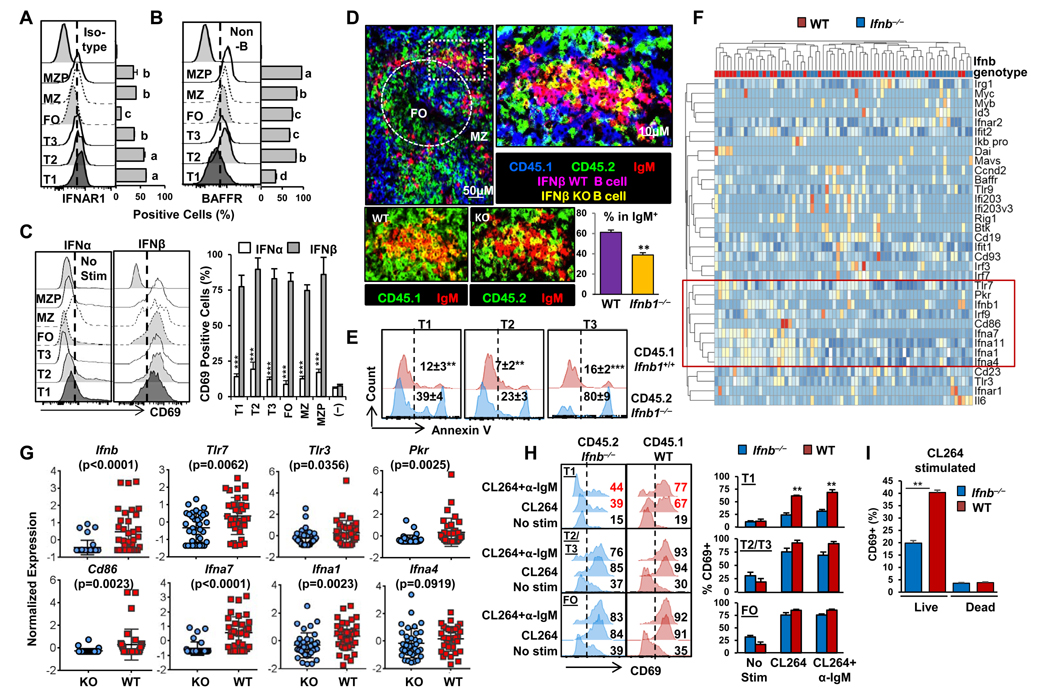

FACS analysis revealed that T1 and T2 B cells expressed the highest levels of IFNαR1 (Fig. 1A). As has been reported, BAFF receptor (BAFFR) is upregulated at the T2 B cell stage and is relatively lower on T1 B cells (16) (Fig. 1B). Stimulation of the sorted B cells in vitro confirmed that high affinity IFNβ exhibited increased ability to stimulate all B cell subsets, compared to IFNα (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Endogenous IFNβ regulates survival and development of transitional B cells. (A–B) Flow cytometry quantification of (A) IFNAR1 and (B) BAFFR expression in the indicated subsets of B cells in B6 mouse spleen (one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001; groups shown with different letters are significantly different from each other, n = 4). (C) Flow cytometry quantification of CD69 expression in the indicated subsets of B6 mouse B cells following in vitro stimulation with either IFNβ (200 ng/mL) or IFNα (200 ng/mL) analyzed 4 hrs post stimulation (***P < 0.005 between IFNβ- vs IFNα stimulation response in the same B subset; Unpaired Students t-test, n = 4). (D–G) BM-chimeric mice were generated by reconstitution of CD45.2 Rag1−/− mice with equal numbers of BM derived from CD45.1 Ifnb+/+ (WT) mice and CD45.2 Ifnb−/− (KO) mice. Recipient mice were sacrificed at day 15 post BM transfer. (D) Upper: Confocal imaging analysis of IgM+ WT (magenta) and IgM+ KO (yellow) B cells in a representative spleen section from double-chimeric recipient mice (objective lens = 40×) (left). Boxed area was digitally magnified (right). Lower: Digitally magnified two-color IgM/CD45.1 or IgM/CD45.2 confocal images (left) with a bar graph showing the percent of IgM+ B cells derived from either WT BM or Ifnb−/− BM in the right. (E) FACS analysis of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells in different transitional B cell subpopulations in chimeric mice. (F–G) BioMark qRT-PCR heatmap (F) and dot plot (G) analysis of the expression of the indicated genes in single T1 B cells derived from CD45.1 B6-Ifnb+/+ (n =36) or CD45.2-Ifnb−/− (n =34) (Data in G are mean ± s.d; non-parametric Mann-Whitney test). (H) FACS plots and bar graph quantification of percent CD69+ T1, T2/T3 and FO-B cells six hours after in vitro stimulation with CL264 (a TLR7 agonist) + α-IgM or CL264 alone (I) Quantification of percent CD69+ live or dead T1 B cells six hours after in vitro stimulation with CL264. Unless specified, all data are mean ± s.e.m. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 for WT vs. Ifnb−/−; n = 2–3 mice per group for 2 independent experiments; unpaired Student’s t-test for D, E, G–I).

To explore whether IFNβ plays a role in the survival and development of T1 B cells in vivo, we reconstituted irradiated Rag1−/− recipients with BM from wild-type (WT) B6 Ifnb+⁄+ (CD45.1) mice and Ifnb−/− (CD45.2) mice. This chimeric approach enabled distinction of the effects of endogenous production of IFNβ from exogenous influences. Confocal imaging of spleens during B cell repopulation (Fig. 1D) confirmed that B cells derived from the BM of both WT and Ifnb−/− mice were capable of seeding the same region of the spleen; however, IgM+ B cells of wild-type origin were significantly increased relative to those derived from Ifnb−/− BM. Consistent with this, there was a significantly higher percentage of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells in transitional B cells derived from the B6 Ifnb−/− BM compared to those derived from the WT BM (Fig. 1E). The highest rates of apoptosis were observed in the IgMlo T3 population, suggesting that anergic, antigen engaged Ifnb−/− B cells are especially sensitive to apoptosis (17) (Fig. 1E).

To identify the pathways associated with the altered survival of T1 B cells lacking endogenous expression of IFNβ, we compared the gene expression patterns of T1 B cells isolated from the chimeric mice focusing on expression of 34 genes that have been shown to be associated with type I IFN. CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ T1 B cells (B220+CD93+IgMhiCD23−) were isolated and subjected to single-cell analysis using the Fluidigm BioMark system. In T1 B cells derived from the WT BM, there was heterogeneous expression of Ifnb1, which was most closely clustered with Tlr7, Pkr, Irf9, Cd86 and the Ifna genes (Fig. 1F, red box). In T1 B cells derived from Ifnb−/− BM, there was significantly lower expression of Tlr7, Tlr3, Pkr, Cd86, Ifna7 and Ifna1, suggesting that the endogenous expression of IFNβ can act in an autocrine fashion to affect the expression of nucleic acid sensing and co-stimulatory genes in developing T1 B cells (Fig. 1G and Supplemental Table 1). Consistent with the gene expression data, live T1 B cells lacking endogenous IFNβ exhibited decreased TLR7 agonist-induced CD69 expression, while responses of the other B cell subsets were not significantly affected (Fig. 1H, I). Together, these data suggest that endogenous IFNβ-expressing T1 B cells are initially autonomous, and that their expression of IFNβ plays a key role in their survival and responsiveness to external factors, including externally derived type I IFNs and TLR7 ligands.

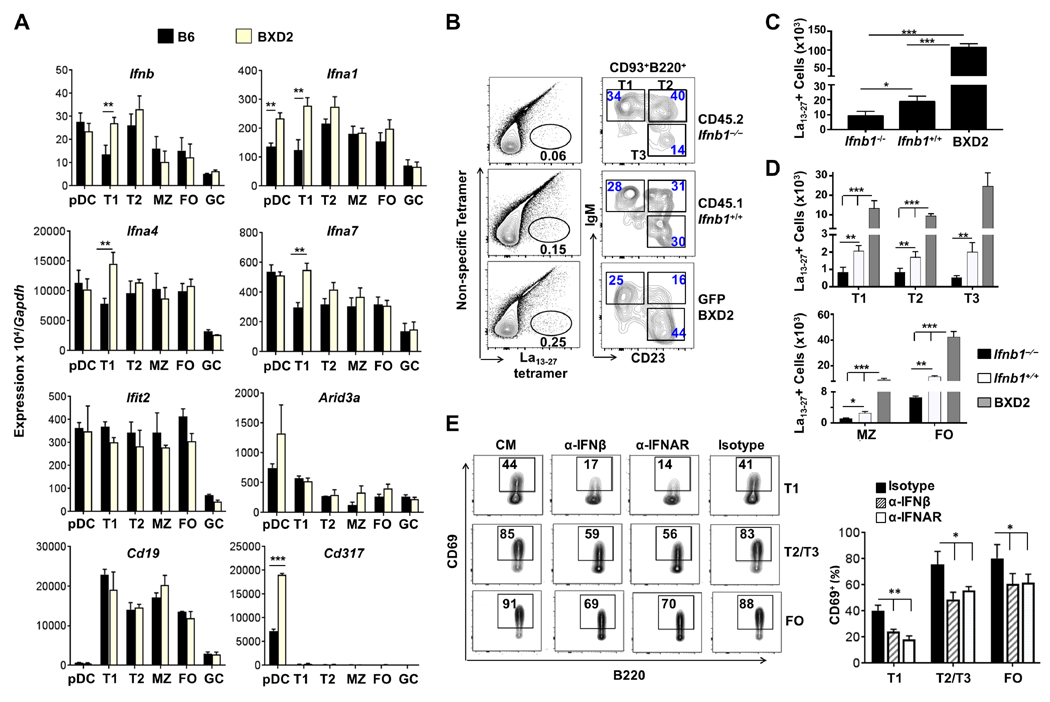

IFNβ promotes survival of autoreactive transitional B cells

We observed previously that, in lupus-prone BXD2 mice, a deficiency of the IFNAR1 ameliorated autoantibody production and autoimmune disease (12, 18). Circulating ARID3a+ transitional and naïve B cells from SLE patients have been shown to express high levels of IFNα (19). Comparison of type I IFN expression in freshly isolated, FACS-sorted cells from BXD2 and age-matched B6 mice revealed significantly elevated levels of endogenous type I IFN genes in T1 but not in other subsets of B cells from BXD2 mice (Fig. 2A). This prominent type I IFN expression in T1 B cells was not associated with increased expression of type I IFN signature gene Ifit2 or with increased Arid3a expression. The lack of significant elevation of type I IFN in pDCs (Fig. 2A) is consistent with the recent finding that, in SLE, type I IFN expression in circulating pDCs was not elevated compared to B cells (20). The identity of sorted cells was verified by high expression of the Cd19 gene in B cells and Cd317 in pDCs (Fig. 2A, lower).

Figure 2.

IFNβ promotes survival of autoreactive transitional B cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in the indicated cell populations in B6 and BXD2 mice. Primer pairs are presented in Supplemental Table 1. ARID3a primers (Forward: CCGTGGACGTCCTCAGATTG; Reverse: TTGGGCTCATTCAAGCACCT). (B–D) BM-chimeric mice (B6-Rag1−/−) were generated by reconstitution with equal numbers of BM cells from CD45.1 B6-Ifnb1+/+ mice, CD45.2 B6-Ifnb1−/− mice and GFP+ BXD2 mice. Recipient mice were sacrificed at day 30 post-reconstitution. (B) Flow cytometry analysis showing the percent of La13–27+ B cells (left) and percent of transitional B cells in the CD93+ La13–27+ subpopulation (right) in recipient mice. (C) Quantitation of absolute numbers of La13–27+ B cells. (D) Quantitation of absolute numbers of La13–27+ B cells in the indicated transitional or mature B cell subpopulation. (E) B cells purified from BXD2 mice were stimulated in vitro with TLR7 agonist CL264 + anti-IgM (α-IgM) in the presence of control medium (CM), α-IFNβ, α-IFNAR, or isotype-control antibody. Representative FACS plots (left) and quantification (right) show the percent CD69+ in T1, T2/T3 and FO B cells four hours after the indicated stimulation. Throughout, data are mean ± s.e.m (n = 4 – 6 mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (A) and by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (B–E).

BXD2 mice produce autoantibodies to RNP antigens, a characteristic of SLE (15); thus, we determined whether endogenous expression of IFNβ by T1 B cells affects the development of La13–27 reactive B cells. Irradiated Rag1−/− mice were reconstituted with BM from CD45.2 B6-Ifnb−/−, CD45.1 B6-Ifnb+⁄+ and CD45.2 GFP+ BXD2 mice (1:1:1). B cells from the BM of B6-Ifnb−/− origin exhibited a significantly lower percentage (Fig. 2B) and total number of La13–27+ B cells (Fig. 2C) and, as found for the double chimeras, a reduction in the total number of transitional and mature B cells at all stages (Fig. 2D) compared to B cells derived from the BM of B6-Ifnb+⁄+ and more strikingly compared to BM of GFP+ BXD2 mice.

To determine whether IFNβ contributes to the TLR7-mediated induction of CD69 in BXD2 autoimmune mice, sorted B cells were stimulated in the presence and absence of neutralizing antibodies to IFNβ or IFNAR (Fig. 2E). Blockade of IFNβ inhibited >50% of T1 B cell activation following CL264+anti-IgM stimulation, and no significant additional inhibition of activation was observed with IFNAR blockade. Together these data suggest that endogenous IFNβ in T1 B cells enables escape of autoreactive T1 B cells from censorship. Importantly, environmental signals, which were equivalent for all B cells in the chimeric mice, did not compensate for the lack of B-cell endogenous IFNβ.

Endogenous IFNβ is associated with distinct subpopulations of T1 B cells in BXD2 mice

To gain insights into the dynamics of Ifnb expression in relation to Ifna genes and Tlr7 in T1 B cells of BXD2 mice, we carried out single-cell gene expression analysis. T1 B cells were FACS sorted and the purity was verified by analysis of single-cell expression of Cd19, Cd23, Cd3 and Cd317, which confirmed that there was no contamination by T cells or pDCs (Supplemental Fig. 1A).

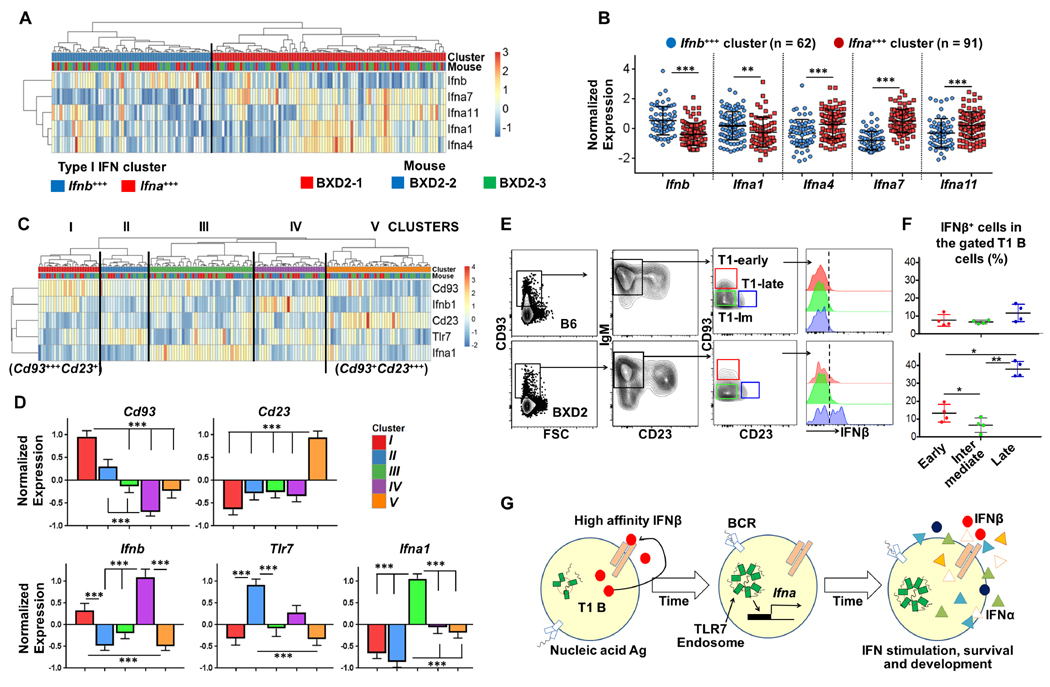

Single-cell analysis of T1 B cells from three BXD2 mice revealed segregation of Ifnbhi versus Ifnalo T1 B cells in T1 B cells in BXD2 mice (Fig. 3A, B, Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Figure 3.

Endogenous IFNβ is associated with distinct subpopulations of T1 B cells in BXD2 mice. (A–D) T1 B cells isolated from the spleen of 3 BXD2 mice were prepared for single cell gene expression analysis (n = 153 data points). (A) Heatmap of type I IFN gene clustering in individual T1 B cells. (B) Dot plots showing the normalized expression type I IFN genes in the Ifnbhi versus Ifnahi cluster (results are mean ± SD; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.005, unpaired t-test). (C) Hierarchical clustering heatmap showing the normalized expression of Ifnb, Ifna1, Tlr7, Cd93 and Cd23 in the five major clusters of T1 B cells. (D) Mean ± (s.e.m) expression of Cd93, Cd23, Ifnb, Tlr7 and Ifna1 in each cluster of T1 B cells. (E) Representative FACS plots of IFNβ expression in the indicated B cell subsets. (F) Quantification of IFNβ+ cells in the indicated B-cell population (mean ± s.d., n = 4) (For D and F, one way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 between the indicated comparisons). (G) A model showing T1 B cell self-production of IFNβ in the induction of TLR7 and other type I IFNs during T1 B-cell development.

Heterogeneity of transitional B cells has been studied extensively in terms of the specificity of the Ag receptor (4) and the expression of costimulatory molecules (21, 22) as well as the relative expression of CD93 and CD23 (23). During development of the most immature T1 B cell stage, acquisition of CD23 coincides with the downregulation of CD93 (23, 24). Heatmap and PC analyses confirmed a distinct inverse expression pattern of Cd93 and Cd23 in single T1 B cells from all three BXD2 mice analyzed (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that downregulation of CD93 coincided with upregulation of CD23 during transitional B-cell maturation in the BXD2 mice (Supplemental Fig. 1D). Therefore, the expression of Ifnb, Tlr7 and Ifna1 was analyzed along with Cd93 and Cd23 leading to the identification of five subpopulations within T1 B cells as shown in Fig. 3C. Cluster I expressed the highest levels of Cd93 and intermediate levels of Ifnb, whereas Tlr7 and Ifna1 were expressed at low levels in this population (Fig. 3C, D). Cluster II and Cluster III were distinguished by upregulation of Tlr7 and Ifna1, respectively, and this was coincident with down-regulation of Cd93 in these two populations (Fig. 3C, D). Cluster IV exhibited the peak expression of Ifnb, and Cluster V exhibited low expression of Ifnb, Ifna, and Tlr7 and the highest Cd23 expression. At the protein level, flow cytometry analysis confirmed that relative to B6 mice, IFNβ expression occurred in CD93+++CD23− and peaked in CD93+CD23dim IgM+ B-cell subpopulations (23) of BXD2 mice (Fig 3E, F).

These data indicate a previously unrecognized level of heterogeneity within the T1 B cell subpopulation. Interestingly, in our single cell data set, the T1 B cells producing the highest levels of type I IFN genes were distinct from those expressing the highest levels of Tlr7 (Fig. 3C). Notably, the T1 B cells expressing the highest Tlr7 represented a relatively small sub-population. This phenomenon was also observed for classical type I IFN response gene Ifit2 (Supplemental Fig. 1E), where Ifit2 upregulation occurred in a small sub-population relative to the Ifna and Ifnb high populations. This suggests additional complexity in the type I IFN network, where distinct type I IFN producing and responding cells occupy a presumed homogenous B cell population. Together, the present findings suggest a hypothetical model in which the endogenous production of IFNβ and autocrine signaling in T1 B cells leads to an ordered unfolding expression of genes, including Tlr7, other type I IFNs and IFN response genes (Fig. 3G). While the exact developmental order of these sub-populations remains uncertain, this cellular heterogeneity may influence and diversify subsequent responsiveness to differentiation signals (25). Although the present study does not exclude the effects of B-cell exogenous factors that may occur after the transitional T1 stage, it does reveal that B-cell endogenous IFNβ influences responses of T1 B cells at a critical peripheral tolerance checkpoint. As SLE is characterized by both early B cell selection abnormalities and polymorphisms in components of the IFNβ enhanceosome (4, 26), future studies would be important to determine if dysregulated autocrine IFNβ during B cell development imprints on the responses of mature B cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from R01-AI-071110 and 1I01BX000600 to J.D.M, R01-AI-083705 to H.-C.H., 2T32AI007051-39 Immunology T32 Training Grant to support J.A.H., P30-AR-048311 P&F Project to J.L., and P30-AR-048311, P30-AI-027767), the LFA Finzi Summer Fellowship to J.A.H, the LRI Novel Research Award to M.W. and H.-C.H., and a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair grant to E.N.F.

References

- 1.Carsetti R, Kohler G, Lamers MC. Transitional B cells are the target of negative selection in the B cell compartment. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1995;181:2129–2140. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norvell A, Mandik L, Monroe JG. Engagement of the antigen-receptor on immature murine B lymphocytes results in death by apoptosis. J Immunol. 1995;154:4404–4413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung JB, Silverman M, Monroe JG. Transitional B cells: step by step towards immune competence. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yurasov S, Wardemann H, Hammersen J, Tsuiji M, Meffre E, Pascual V, Nussenzweig MC. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:703–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekeredjian-Ding IB, Wagner M, Hornung V, Giese T, Schnurr M, Endres S, Hartmann G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control TLR7 sensitivity of naive B cells via type I IFN. J Immunol. 2005;174:4043–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber G, Piehler J. The molecular basis for functional plasticity in type I interferon signaling. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamken P, Lata S, Gavutis M, Piehler J. Ligand-induced assembling of the type I interferon receptor on supported lipid bilayers. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:303–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniguchi T, Takaoka A. A weak signal for strong responses: interferon-alpha/beta revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:378–386. doi: 10.1038/35073080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green NM, Laws A, Kiefer K, Busconi L, Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Trail EH, Yasuda K, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Vogel S, Connor JH, Ploegh H, Eilat D, Rifkin IR, van Seventer JM, Marshak-Rothstein A. Murine B cell response to TLR7 ligands depends on an IFN-beta feedback loop. J Immunol. 2009;183:1569–1576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheikh F, Dickensheets H, Gamero AM, Vogel SN, Donnelly RP. An essential role for IFN-beta in the induction of IFN-stimulated gene expression by LPS in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96:591–600. doi: 10.1189/jlb.2A0414-191R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deonarain R, Verma A, Porter AC, Gewert DR, Platanias LC, Fish EN. Critical roles for IFN-beta in lymphoid development, myelopoiesis, and tumor development: links to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2230460100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Fu YX, Wu Q, Zhou Y, Crossman DK, Yang P, Li J, Luo B, Morel LM, Kabarowski JH, Yagita H, Ware CF, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Interferon-induced mechanosensing defects impede apoptotic cell clearance in lupus. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2877–2890. doi: 10.1172/JCI81059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W566–570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conrad S, Azizi H, Hatami M, Kubista M, Bonin M, Hennenlotter J, Sievert KD, Skutella T. Expression of Genes Related to Germ Cell Lineage and Pluripotency in Single Cells and Colonies of Human Adult Germ Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:8582526. doi: 10.1155/2016/8582526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton JA, Li J, Wu Q, Yang P, Luo B, Li H, Bradley JE, Taylor JJ, Randall TD, Mountz JD, Hsu HC. General Approach for Tetramer-Based Identification of Autoantigen-Reactive B Cells: Characterization of La- and snRNP-Reactive B Cells in Autoimmune BXD2 Mice. J Immunol. 2015;194:5022–5034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, Walsh ME, Ng LG, MacKay F, Rao SP, Kalled SL, Scott ML. B cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family acts through separate receptors to support B cell survival and T cell-independent antibody formation. J Immunol. 2004;173:2331–2341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrell KT, Benschop RJ, Gauld SB, Aviszus K, Decote-Ricardo D, Wysocki LJ, Cambier JC. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 2006;25:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JH, Li J, Wu Q, Yang P, Pawar RD, Xie S, Timares L, Raman C, Chaplin DD, Lu L, Mountz JD, Hsu HC. Marginal zone precursor B cells as cellular agents for type I IFN-promoted antigen transport in autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:442–451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward JM, Ratliff ML, Dozmorov MG, Wiley G, Guthridge JM, Gaffney PM, James JA, Webb CF. Human effector B lymphocytes express ARID3a and secrete interferon alpha. J Autoimmun. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodero MP, Decalf J, Bondet V, Hunt D, Rice GI, Werneke S, McGlasson SL, Alyanakian MA, Bader-Meunier B, Barnerias C, Bellon N, Belot A, Bodemer C, Briggs TA, Desguerre I, Fremond ML, Hully M, van den Maagdenberg A, Melki I, Meyts I, Musset L, Pelzer N, Quartier P, Terwindt GM, Wardlaw J, Wiseman S, Rieux-Laucat F, Rose Y, Neven B, Hertel C, Hayday A, Albert ML, Rozenberg F, Crow YJ, Duffy D. Detection of interferon alpha protein reveals differential levels and cellular sources in disease. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017;214:1547–1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims GP, Ettinger R, Shirota Y, Yarboro CH, Illei GG, Lipsky PE. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4390–4398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palanichamy A, Barnard J, Zheng B, Owen T, Quach T, Wei C, Looney RJ, Sanz I, Anolik JH. Novel human transitional B cell populations revealed by B cell depletion therapy. J Immunol. 2009;182:5982–5993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6834–6840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleiman E, Salyakina D, De Heusch M, Hoek KL, Llanes JM, Castro I, Wright JA, Clark ES, Dykxhoorn DM, Capobianco E, Takeda A, Renauld JC, Khan WN. Distinct Transcriptomic Features are Associated with Transitional and Mature B-Cell Populations in the Mouse Spleen. Front Immunol. 2015;6:30. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soni C, Wong EB, Domeier PP, Khan TN, Satoh T, Akira S, Rahman ZS. B cell-intrinsic TLR7 signaling is essential for the development of spontaneous germinal centers. J Immunol. 2014;193:4400–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu Q, Zhao J, Qian X, Wong JL, Kaufman KM, Yu CY, Hwee Siew H, G. Tan Tock Seng Hospital Lupus Study. Mok MY, Harley JB, Guthridge JM, Song YW, Cho SK, Bae SC, Grossman JM, Hahn BH, Arnett FC, Shen N, Tsao BP. Association of a functional IRF7 variant with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:749–754. doi: 10.1002/art.30193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.