Abstract

Background

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) are a standard for identifying and reporting laboratory investigations that were developed and are maintained by the Regenstrief Institute. LOINC codes have been adopted globally by hospitals, government agencies, laboratories, and research institutions. There are still many healthcare organizations, however, that have not adopted LOINC codes, including rural hospitals in low- and middle- income countries. Hence, organizations in these areas do not receive the benefits that accrue with the adoption of LOINC codes.

Methods

We conducted a literature search by utilizing PubMed, CINAHL, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, and the Biomed Central database to look for existing publications on the benefits and challenges of adopting LOINC. We selected and reviewed 16 publications and then conducted a case study via the following steps: (1) we brainstormed, discussed, analyzed, created and revised iteratively the patient’s clinical encounter (outpatient or ambulatory settings) process within a laboratory department via utilizing a hypothetical patient; (2) we incorporated the work experience of one of the authors (CU) in a rural hospital laboratory department in Nigeria to break down the clinical encounter process into simpler and discrete steps and created a series of use cases for the process; (3) we then analyzed and summarized the potential usage of LOINC codes (clinically, administratively, and operationally) and the benefits and challenges of adopting LOINC codes in such settings by examining the use cases one by one.

Results

Based on the literature review, we noted that LOINC codes’ ability to improve laboratory results’ interoperability has been recognized broadly. LOINC-coded laboratory results can improve patients’ safety due to their consistent meaning as well as the related reduction of duplicate lab tests, easier assessment of workloads in the laboratory departments, and accurate auditing of laboratory accounts. Further, the adoption of LOINC codes may motivate government agencies to upgrade hospitals’ infrastructures, which could increase the possibility of international recognition of laboratory test results from those hospitals over the long term. Meanwhile, a lack of LOINC codes in paper format and a lack of LOINC codes experts are major challenges that may limit LOINC adoption.

Conclusion

In this paper, we intend to provide a snapshot of the possible usage of LOINC codes in rural hospitals in low- and middle-income countries via simpler and detailed use cases. Our analysis may aid policymakers to gain a deeper understanding of LOINC codes in regard to clinical, administrative, and operational aspect and to make better-informed decisions in regard to LOINC codes adoption. The use case analysis also can be used by information system designers and developers to reference workflow within a laboratory department. We recognize that this manuscript is only a case study and that the exact steps and workflows may vary in different laboratory departments; however, the core steps and main benefits should be consistent.

Keywords: Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), Hospital-laboratories/standards, Hospital administration, Health policy

Introduction

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) are a universal standard for identifying medical laboratory observations and investigations that, since 1994, have been developed and maintained by a U.S. non-profit organization, the Regenstrief Institute [1]. LOINC codes have continued to expand to other fields of medicine, including pharmacy, radiology, and medical imaging [1]. LOINC codes are currently used in more than 165 countries across the globe [1]. They have been adopted by many hospitals in developed and low- and middle- income nations, research institutions, and government agencies in the United States, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), public health departments, healthcare provider networks, and insurance companies, and are part of the Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [2]. For example, 806-0 (Leukocytes [#/volume] in Cerebral spinal fluid by Manual count) is one LOINC code example. Six dimensions are utilized to describe this observation: Component (analyte)[white blood cells], Property [number concentration], Time [point in time], System (specimen)[cerebral spinal fluid], Scale [quantitative], and Method [manual count] [1].

LOINC codes were developed mainly to facilitate interoperability among different information systems, providers, and entities to allow sharing and reusing lab test results accurately. Before the inception of LOINC codes, there was no universally recognized or accepted set of codes by which laboratory results could be reported and shared globally. Each hospital laboratory developed its own local codes to report its laboratory test results. This situation led to many challenges in ordering laboratory tests as well as reporting, interpreting, comparing, and sharing laboratory results [2]. Although many urban hospitals, especially large academic institutions, in developed and low- and middle-income countries have been able to overcome some challenges by adopting LOINC codes, the challenges still persist in those hospitals that have not adopted LOINC codes, such as rural hospitals in low- and middle-income countries.

According to the Ohio Health Information Partnership’s 2013 survey: “12% of its hospital participants were using LOINC codes to send results to providers” [3]. In recent years, the electronic health record systems adoption rate in hospitals (72% in 2011, 96% in 2015) and physicians’ offices (20.9% in 2004, 86.9% in 2015) has increased rapidly in the United States, and 88% of U.S. hospitals reported electronic laboratory results in 2015 [4]. It has been recognized repeatedly in different countries, including some low- and middle- income countries, that interoperability is difficult to achieve, adopt, and implement and that maintaining different data standards is needed but not sufficient to achieve the true interoperability [5, 6]. In terms of standards adoption, according to one report, lack of enforcement and regulation is still the main challenge [7].

The main objective of our work is to articulate the potential benefits and challenges of adopting LOINC in a laboratory department via detailed workflow and use case analysis. This work may help the targeted audience-policymakers, who may not be familiar with the technical details of LOINC codes or the embedded information systems to make well-informed decisions about the adoption of LOINC codes in an organization. We conducted a literature review and a case study to demonstrate the possible step-by-step usage of LOINC codes in a laboratory department. Although the workflow and steps may vary among organizations, the main benefits and usage should not vary significantly. Furthermore, the detailed workflow analysis and use case analysis may be utilized as a reference for laboratory information system designers. We used a rural hospital laboratory in a low- and middle-income country as the example.

Methods

This work was initially conducted (literature search, review, laboratory department workflow analysis, and use cases analysis) by CU when he pursued his MPH at Ohio University and worked as a research assistant for XJ during 2014–2015. CU drafted the first version of the manuscript. XJ designed the project based on three factors: the limited knowledge and awareness of LOINC codes outside of the health informatics field; the critical role of LOINC codes in solving interoperability in the laboratory setting, especially with the high adoption rate of electronic health record systems globally; and the laboratory medicine background and work experience of CU. XJ guided the work and conducted substantial revising, reorganizing, and rewriting of the manuscript.

First, we conducted a literature search through the Ohio University library, using PubMed, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and the Biomed Central database. We used the filters human, abstract, and full text and separated the keywords by the term or or and on all of the searches. Due to the paucity of literature, there was no restriction on the publication date, but the publication language search was restricted to the English language.

Based on the main purpose of this study, we utilized the following search strategies:

“Benefits or advantages or importance” (definitions, synonyms, singular, plural);

“Challenges or disadvantages or barriers or problems” (definitions, synonyms, singular, plural);

“Adopting or implementing or establishing” (definitions, synonyms, singular, plural);

“LOINC or LOINC codes or LOINC code or logical observation identifiers names and codes” (definitions, singular, plural);

“Logical observation identifiers names and codes” as a MeSH major topic in PubMed.

We then conducted the following searches:

(1) and (3) and (4);

(2) and (3) and (4);

(5).

LOINC became a MeSH term in 2003 and we used it as a major MeSH term to search PubMed until March 13, 2017. We then went through all of the results manually to (a) remove duplicates; (b) select relevant publications that concern adoption and use of LOINC, including benefits and/or challenges; (c) look for available full-text publications; and (d) look for relevant references of the selected publications.

We also searched the ACM Digital Library, utilizing LOINC as the search term. All 19 records were included and considered in the literature review pool. There are five more publications suggested by experts; however, these recommended publications are about the general adoption of healthcare data standards and are not specifically about LOINC codes. Therefore, we included these five publications in the discussion, not in the literature review results.

Second, CU conducted the analysis, which was similar to model-based (i.e., use cases) analysis. XJ asked heuristic questions, from a reader’s and a medical and an information system designer’s point of view. The detailed breakdowns, analysis, and presentation of the results facilitate the analysis in a systematic, formal, and structured manner. The process is a pure abstract and intellectual and can be influenced largely by analysts’ background knowledge and experience. CU obtained a bachelor’s degree in laboratory medicine and a master’s degree in medical microbiology and worked in a rural hospital laboratory in Nigeria for 2 years.

Specifically, we (1) summarized the general workflow of a patient’s clinical encounter in a laboratory department (outpatient or ambulatory setting); the analysis started with the general, coherent, and complete clinical encounter process by utilizing a hypothetical patient, without considering LOINC codes; (2) broke down the workflow into simpler, discrete and detailed steps; (3) identified the possible steps and actual actions for which LOINC codes can be used; and (4) articulated and illustrated the potential impacts of LOINC codes in each step. The analysis and presentation have gone through iterative discussions and revisions. We intend to utilize the workflow of the use cases as vehicles to articulate the exact processes, to demonstrate how LOINC codes can be utilized in a laboratory setting to the targeted audiences, and to facilitate communication.

Results

Literature review results

We selected 16 publications from the literature review pool. Two of the 19 records from ACM are duplicates with other search results. The rest of the 17 records are irrelevant to our topic. Although the main focus of most of the selected publications was not detailed usage, benefits, or challenges of LOINC adoption, the publications nevertheless mentioned the benefits and/or challenges. Table 1 provides a summary of the results.

Table 1.

Literature on usage, benefits, and challenges of LOINC adoption

| Reference | Settings | Benefits of LOINC | Secondary usage | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDonald et al. [2] | N/A | Semantic interoperability | Data sharing, aggregation across systems | Variations of local codes, mapping |

| Lin et al. [8] | Large health systems | Consistency, interoperability, usefulness | Knowledge management, information retrieval, data integration, clinic decision support (CDS), biomedical inference [9] | Semantic interoperability, internal auditing, automatic consistency check |

| Scichilone [10] | N/A | Reusability, unique identity, sharable, interoperability | Reuse of electronic health record | Complete, broad, and accurate coverage |

| Wu et al. [11] | N/A | Reusability, aggregate data | Quality measurement, public health reporting | Mapping from local codes to LOINC codes |

| FDA adopts LOINC standard [12] | Pharmaceutical and biological submissions to FDA | Standardized communication, facilitation of lab results understanding, analysis, and exchange | N/A | N/A |

| Vreeman [13] | N/A | Interoperable health information exchange, no cost | Efficient processing and storage of clinical data | Translation into different languages |

| Deckard et al. [14] | N/A | Interoperability of genetic data, augmenting of narrative reports, structured discrete reporting | Automatic processing of genetic test reports | Complete coverage, varied styles of reports |

| ONC SHP [3] | Health information exchange | Facilitation of health information exchange | Clinical decision support, trending analysis, population health management | Mapping, translation, adequate time and resources, maintenance, human interaction |

| Beitia et al. [15] | Health information exchange | Facilitation of health information exchange | Provision of data for CDS and guidelines, aggregated data analysis, public health usage | Combination exams map to single LOINC code, comprehensive coverage |

| Wilson et al. [16] | N/A | Facilitation of efficiency, reuse, interoperability, secondary analysis | Collection and transmission of patient assessment data, aggregation | Standard documentation |

| Abhyankar et al. [17] | N/A | Reporting of newborn screening results more quickly and efficiently, facilitation of health information exchange, standardized follow-up, infrastructure | Aggregated results, facilitation of research, quality assurance, continuity of operations | Competing priorities, lack of expertise, lack of funding |

| Sheide et al. [18] | N/A | Provision of structured data in claims, increased specificity of clinical documentation, accurate coding, automatic audit process, improvement of submission of claims and appeals data | Support analysis, data aggregation, facilitation of collection and organization of patient data | Compliance requirements in health IT, effective navigation of patient health records |

| Aller [19] | N/A | Standardized test identifiers, transportable rule sets, e-transmission of results for public health | Comparison and combining of lab test results | Automatic reporting, transfer, consistent coding |

| Lin et al. [20] | Large institutions | Standardized codes for interoperability clinical data sharing | Support of greater accuracy, decreased time and cost when mapping | Mapping challenges: human errors, mapping to different granularity, lack of knowledge of the lab tests and LOINC naming rules |

| Baorto et al. [21] | Large institutions | Automatic data pooling, data exchange for lab results | Aggregation and comparison of data from different sources | Mapping between local codes to LOINC codes |

| Lab interoperability cooperative [22] | N/A | e-submission of lab results to public health departments, timely and accurate reporting, integrate data into hospital systems | Reduction of cost, support of coordinated care, improved population outcomes | Complexity, expectations, education, leader, priorities, staff, resources, connectivity, return on investment, urgency |

Overview of the typical workflow in a laboratory department

Table 2 presents all of the actors and their roles for the use case scenarios. The typical workflow, step-by-step breakdowns of a patient’s clinical encounter, and possible usage of LOINC codes are presented below.

Table 2.

Main actors and their roles in a clinical encounter in a laboratory department

| Actor | Role description |

|---|---|

| HRO (hospital records officer) | Serves as contact person between a patient and hospital departments, ensures that a patient’s information is documented in the patient’s record |

| Physician | Conducts the clinical consultation and orders laboratory tests |

| LRO (laboratory registration officer) | Serves as the link between the laboratory department and other hospital departments, ensures that a patient’s tests are properly billed and registered before specimens are collected |

| Cashier | Staff member of the finance department who collects payments for all laboratory bills sent to the laboratory department |

| MLT (medical laboratory technician) | Collects, registers, labels, and stores the specimens |

| MLS (medical laboratory scientist) | Runs the test, reports the results, which can be coded in LOINC codes, and sends the results to the physician |

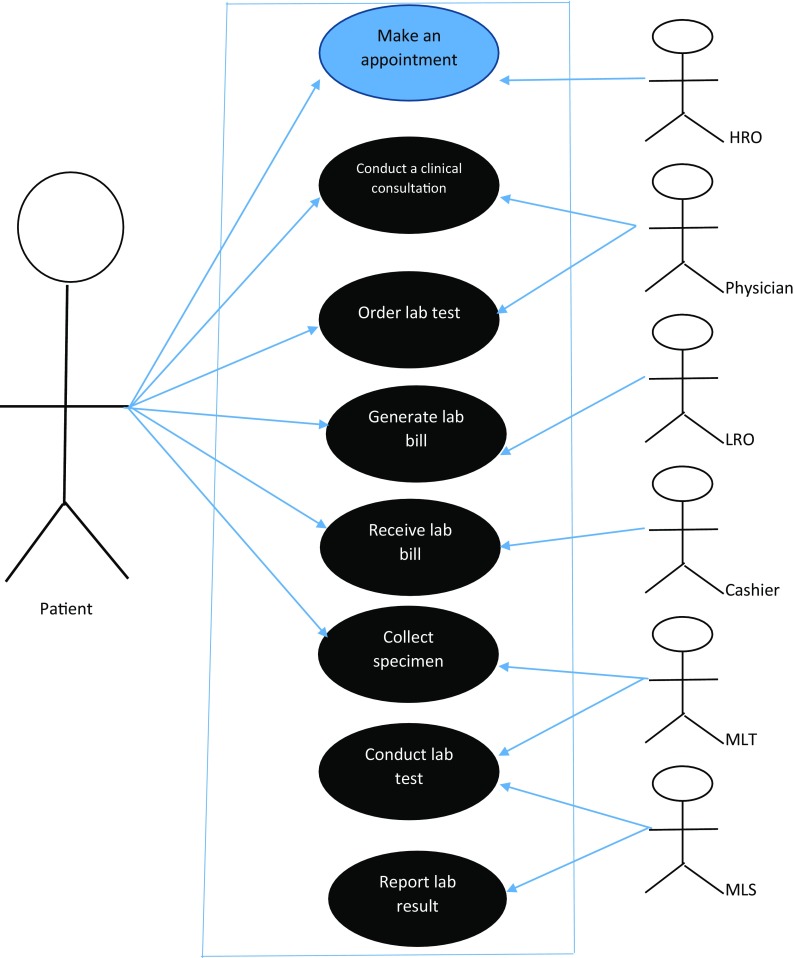

Figure 1 shows use cases of a patient’s clinical encounter in a laboratory department.

Fig. 1.

Use case scenario of a patient’s clinical encounter in a laboratory department (blue oval: LOINC codes cannot be applied; black oval: LOINC codes can be applied. HRO: hospital records officer; LRO: lab registration officer; MLT: medical lab technician; MLS: medical lab scientist)

The workflow breakdowns in a laboratory department

Steps 1–10 represent the typical workflow in a rural hospital laboratory department. The flow may vary in different hospitals, especially, in hospital laboratories with more resources and a better-organized system [20].

Step 1: Patient → HRO

A patient must contact the HRO to schedule an appointment to see a physician. The HRO will open a folder for a new patient or add a new appointment to an existing patient’s folder.

Step 2: Patient → Physician

On the day of the appointment, the patient will meet with the physician for a clinical consultation. During the consultation, the physician may order a laboratory test.

Step 3: HRO ↔ Physician

After the clinical consultation, the physician will give a copy of the laboratory request form to the patient, retain a copy in the patient’s folder, and send it back to the HRO for documentation.

Step 4: Patient → LRO

The LRO will receive the laboratory request form from the patient and bill the patient.

Step 5: Patient → Cashier

The patient will take the laboratory request form with the bill to the cashier, who will sum the total bill, receive payment from the patient, and issue a receipt for the payment.

Step 6: Patient → MLT

The patient will collect the laboratory request form and receipt of payment from the cashier and take them to the MLT. The MLT will then collect the specimen from the patient and label the specimen.

Step 7: MLT → MLS

At this step, only the registered and labeled patient’s specimen and laboratory request form will be sent to the MLS. The MLS will perform the test and report the results.

Step 8: MLS → MLT → LRO → HRO → Physician

After analysis of the specimen, the MLS will prepare a complete laboratory report and send it back to the MLT, who will record the laboratory results. The MLT will then send the report to the LRO for documentation. After documentation by the LRO, the report will be sent to the HRO for final documentation in the hospital record and patient’s folder for reference purposes.

Step 9: Patient → HRO → physician

When the patient returns for a laboratory review, the HRO will schedule another appointment with the physician for the patient. The HRO will send the patient folder that contains the laboratory results to the physician on the appointment date.

Step 10: Patient → physician

On the scheduled date, the patient will meet the physician for a review of the laboratory results. The physician will review the patient’s laboratory results by first double checking whether the laboratory request that is documented in the patient’s folder corresponds to the ones sent by the MLS.

Possible usage of LOINC codes within the laboratory department workflow

Table 3 provides a summary of where and how LOINC codes may be used during a clinical encounter.

Table 3.

Possible usage of LOINC codes during a patient’s clinical encounter

| Steps | Where can LOINC codes be used? | How can LOINC codes be used? |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Patient → Physician | During the clinical consultation with the patient, the physician orders a laboratory test, which can be coded in LOINC code |

| 4 | Patient → LRO | The LRO receives the lab form from the patient and itemizes the cost for each test, which can be listed in LOINC codes, and bills the patient |

| 5 | Patient → Cashier | The cashier sums the total bill for all of the individual lab tests, which can be coded in LOINC codes, and collects payment from the patient |

| 6 | Patient → MLT | The MLT succinctly labels the patient’s specimen in LOINC codes/lab reference number for identification |

| 7 | MLT → MLS | The MLS reports and documents all of the patient’s test results, which can be coded in LOINC codes |

| 10 | Patient → Physician | During the review of laboratory results, the physician checks the consistency of the lab order and the reported test results via LOINC codes and interprets the results |

Results interpretation and discussion

The literature review shows that the majority of the identified benefits of LOINC are in facilitating interoperability for sharing, i.e., secondary usage of the lab test results among different entities, such as hospitals, physicians’ offices, insurance companies, and government agencies. The mapping between local laboratory codes and LOINC codes as well as translation of LOINC codes from English into other languages have been identified as challenges when adopting LOINC. Efforts have been focused on mapping local codes to LOINC codes accurately and efficiently, either manually or automatically. Publications have identified benefits and challenges in adopting health information technologies in health care, in general. Benefits include efficient and improved clinical documentation, easier access to patient information, and improved patient safety and privacy [23]; identified barriers include cost [23, 24], politics, technical infrastructure, end users’ resistance, and shortage of workforce [24, 25]. Further, there is a lack of detailed illustration and analysis of possible LOINC usage, especially on the hospital administration side.

Potential benefits of adopting LOINC

Improved interoperability of laboratory test results

LOINC codes were developed to improve the interoperability of laboratory test results [2]. The universal codes can facilitate sharing, reusing, communicating, aggregating, comparing, and interpreting laboratory test results among different entities more efficiently and automatically. The consistently represented laboratory results by LOINC codes can (a) reduce duplicate tests, especially in referral cases [2, 3, 8, 10–22], which can save time and cost (Step 4); (b) interpret the laboratory results accurately, without ambiguity [8, 10, 18, 20, 22]; and (3) improve quality control and measurement over time or across entities’ borders [19, 21].

Improved hospital administration

Consistent and specific LOINC codes can be utilized to improve hospital administration. Nevertheless, labeling mistakes or inconsistent usage of multiple local codes for the same test (Step 5) may lead to inaccurate interpretation of the laboratory results. Consistent LOINC codes can be utilized to reduce such errors. In addition, LOINC codes can be utilized to aid in effective billing, better hospital financial management, and accurate locating of laboratory results. During a patient’s clinical encounter, each time a physician orders a laboratory test, a copy of the laboratory request form coded in LOINC codes can be placed in the patient’s record folder, which will be returned to the HRO (Step 2). The original copy of the patient’s laboratory test request form is sent to the LRO, who can bill the tests in LOINC codes and send the bill to the cashier for payment collection (Step 3). This helps to document, track, locate, and transmit test orders among different departments. Due to consistent usage of LOINC codes among the HRO, physician, LRO, and cashier, auditing of laboratory accounts becomes straightforward. With LOINC codes, hospital staff members can easily locate the laboratory results, as described in Steps 8 and 9.

The adoption of LOINC codes also can aid hospital administrators to assess the workload of the personnel in the hospital laboratory (Step 7) more accurately and conveniently [16–18]. The use case scenario in Fig. 1 shows how the HRO and LRO keep a record of each test requested by the physician. With LOINC codes, aggregated laboratory requests made within a certain period can be generated accurately and conveniently. The LOINC codes can protect patients’ privacy and confidentiality to some extent, especially when the diseases are stigmatized (Step 7). For instance, LOINC codes, rather than explicit test names, can be utilized for HIV/AIDS test.

Broader recognition of laboratory test results

Adoption of LOINC codes by one organization, improves the recognition of the laboratory results among other organizations, including the government agencies. As a result, more resources or support may be available to upgrade the infrastructure of the organization, which may contribute to further improvement of the laboratory department and the organization.

Potential challenges of adopting LOINC

Lack of basic infrastructure

Funding and lack of resources have been identified as challenges for LOINC adoption [17, 22], especially for many rural hospitals in low- and middle-income countries, where a basic infrastructure that includes a stable electricity supply, clean running water, and an adequate supply of medications is lacking [25]. Often, the laboratories in rural hospitals depend on generators for electricity and obsolete equipment, such as hand-operated centrifuges, light-operated monocular microscopes, and box-made incubators, which could occasionally lead to erroneous laboratory results. Currently, LOINC codes are published only electronically, which can make their adoption difficult in rural settings due to a lack of computers, Internet connections, or printers as well as the inability to get an updated paper version twice a year, when LOINC codes are updated.

Workforce shortage and healthcare professionals’ resistance

Workforce shortage of trained personnel who have technical expertise in LOINC codes and an understanding of laboratory medicine can be a big challenge for LOINC codes adoption [3, 17, 18, 20, 22]. In addition, the mapping of local codes to LOINC requires specific expertise and is time-consuming [2, 3, 11, 20–22]. Further, the mapping may require extra funding, which can be difficult to acquire when there is no clear evidence of any return on investment [2, 23].

The adoption of LOINC codes, similar to the adoption of other health information technologies, may face resistance from healthcare professionals and bureaucracy [24]. Healthcare professionals’ resistance to newly introduced technologies or programs is common in low- and middle-income countries due to fear of a loss of job security [24].

Comparing with other existing publications

Although there are publications related to healthcare data standards, adoption, challenges, and recommendations globally [5, 7], including Africa [26], the focus of these publications is at the macro level (such as governance, regulations, or enforcement) in terms of challenges and recommendations. We feel that our work is complementary to existing publications, as the focus of our work is to illustrate the detailed usage and benefits at the individual organization level. There are also other publications related to information system design in the pathology department [27, 28]. Though pathology is a major part of the laboratory, the laboratory department has a much broader scope. In addition, Muirhead et al’s model focuses on economic aspects and cost per slide in a pathology department [28], whereas Patterson et al’s work has similarities to our analysis. Both, however, focus on optimizing clinical processes and improving clinical efficiency only in the pathology department. Our work intends to illustrate the exact and detailed processes whereby LOINC codes can fit into the larger laboratory setting. Further, in our project, the main purpose is to illustrate potential benefits and challenges, and use case analysis is utilized as a method to articulate the exact processes, demonstrate the usage, and facilitate communications. Therefore, we feel that our work is complementary to that of the earlier literature, as there is a different granularity in the level of our focus. Nevertheless, we do believe that existing publications can be utilized as a reference to position our work and to identify the uniqueness of our project.

Limitations of this study

One of the main limitations of this study is that we use a descriptive case study and a typical workflow analysis rather than incorporating multiple workflows from multiple hospital settings. We utilized a classic analytic method in software engineering: use case analysis to articulate and illustrate the typical workflow in a hospital laboratory department. We believe, however, that the core steps and the main usage of LOINC codes will be consistent across settings, even though the actual steps may vary in different settings. Although we believe that this study fills a gap by providing a snapshot of how LOINC codes may be utilized after adoption and their possible benefits and challenges, we do realize that this literature review and case study can be utilized only as a starting point. More accurate measures should be obtained via well-designed observational studies and surveys.

Another limitation of this study is that we incorporated CU’s laboratory medicine background, both educational and practical, without incorporating a formal validation process. XJ also has formal medical education and, indeed, has previous system analysis and design experience; therefore, we believe the iterative discussions and revisions during the analysis provide a sense of validation and that, as a case study, this may be acceptable. We do recognize, however, that a formal validation process by external personnel would be ideal.

Conclusion

This study intended to create a snapshot of the possible usage of LOINC codes in rural hospitals in low- and middle-income countries. Despite the lack of LOINC codes in paper format, lack of basic infrastructure to operate LOINC, and shortage of LOINC codes experts, the benefits of adopting LOINC codes in rural hospital laboratories outweigh the challenges, especially in terms of improving interoperability of lab test results and efficient and accurate hospital administration via more accurate and convenient workload assessments. Further, the adoption of LOINC codes may make the auditing process in the laboratory department more efficient and increase hospital revenue. Our analysis may provide policymakers with a better understanding of the detailed usage of LOINC codes in regard to clinical, administrative, and operational aspects and aid them to make better-informed decisions about LOINC codes adoption. The detailed clinical encounter use case analysis can be used as a workflow reference for laboratory information system designers and developers.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank Dr. Clem McDonald for his constructive suggestions sincerely. This study is supported by Ohio University College of Health Sciences and Professions start-up funds and Department of Social and Public Health.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.“LOINC from Regenstrief.” https://loinc.org/. Accessed 08 May 2017.

- 2.McDonald C, Huff S, Suico J, Hill G, Leavelle D, Aller R, Forrey A, Mercer K, DeMoor G, Hook J, Williams W, Case J, Maloney P. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clin Chem. 2003;49(4):624–633. doi: 10.1373/49.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.S. H. P. ONC, State HIE bright spots synthesis lab exchange. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/lab_exchange_bright_spots_synthesis_final_09302013.pdf. 2013.

- 4.ONC. Health IT dashboard. http://dashboard.healthit.gov/index.php. 2015.

- 5.WHO. WHO forum on health data standardization and interoperability. WHO, Geneva, 2012.

- 6.Kijsanayotin B, Thit WM. Global health informatics: Principles of ehealth and mhealth to improve quality of care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017. 12 Health Information Standards and Interoperability; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L. Recommendations for a global framework to support health information exchange in low- and middle-income countries. 2016.

- 8.Lin M, Vreeman D, McDonald C, Huff S. Auditing consistency and usefulness of LOINC use among three large institutions—Using version spaces for grouping LOINC codes. J Biomed Inf. 2012;45:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodenreider O. Biomedical ontologies in action: role in knowledge management, data integration and decision support. Yearb Med Inform. 2008;47:67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scichilone R. The Benefits of Using SNOMED CT and LOINC in Assessment Instruments. J AHIMA. 2008;79(9):56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Finnell J, Vreeman D. Evaluating congruence between laboratory LOINC value sets for quality measures, public health reporting, and mapping common tests. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, pp. 1525–1532. 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.FDA Adopts LOINC Standard. J AHIMA. 2015;86(7):13. http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/103422821/fda-adopts-loinc-standard

- 13.Vreeman D, Chiaravalloti M, Hook J, McDonald CJ. Enabling international adoption of LOINC through translation. J Biomed Inf. 2012;45:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deckard J, McDonald C, Vreeman D. Supporting interoperability of genetic data with LOINC. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2015;22:621–627. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beitia A, Kuperman G, Delman B, Shapiro J. Assessing the performance of LOINC® and RadLex for coverage of CT scans across three sites in a health information exchange. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, pp. 94–102. 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wilson P, Scichilone R. LOINC as a data standard. J AHIMA 2011;82:44–47. [PubMed]

- 17.Abhyankar S, Goodwin R, Sontag M, Yusuf C, Ojodu J, McDonald C. An updateontheuseofhealthinformation technology innewbornscreening. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39:188–193. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheide A, Wilson P. Reading Up on LOINC. J AHIMA. 2013;84(4):58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aller R. For vendors, LOINC a fast track to the future. CAP Today. 2003;17(11):34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin M, Vreeman D, McDonald C, Huff S. Correctness of voluntary LOINC mapping for laboratory tests in three large institutions. In: AMIA 2010 Symposium Proceedings, pp. 447–451. 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Baorto D, Cimino J, Parvin C, Kahn M. Combining laboratory data sets from multiple institutions using. Int J Med Inf. 1998;51:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(98)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lab Interoperability Cooperative. How to conquer the top 10 challenges/tricks of the trade and straightforward advice. http://www.cybermanual.com/how-to-conquer-the-top-10-challenges_tricks-of-the-trade.html.

- 23.Lessons learned from a journey to EMR. Health Manag Technol. 2009;30(11):24–7. [PubMed]

- 24.Oak M. A review on barriers to implementing health informatics in developing countries. J Heal Informatics Dev Ctries. 2007;1(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korganonkar R. Adoption of information system by Indian hospitals: challenges and roadmap. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2014;5(2):473–479. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moodley D, Seebregts C, Pillay A, Meyer T. An ontology for regulating eHealth interoperability in developing African countries. In: International Symposium on Foundations of Health Informatics Engineering and Systems, pp. 107–124. 2013

- 27.Patterson M, Bond R, Mulvenna M, Reid C, McMahon F, McGowan P, Cormican H. The design of a computer simulator to emulate pathology laboratory workflows. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, p. 25. 2016.

- 28.Muirhead D, Aoun P, Powell M, Juncker F, Mollerup J. Pathology economic model tool: a novel approach to workflow and budget cost analysis in an anatomic pathology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(8):1164–1169. doi: 10.5858/2000-0401-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]