Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide. Since its first description as a neurological disorder by James Parkinson (1755–1824) in 1817, many important discoveries have been made during this 200 years of PD research history. These milestones have revealed many aspects of PD, including clinical and pathological characteristics, anatomy and neurochemistry, environmental and genetic factors, hypothesis of peripheral to central spread, and advances in diagnostic technology and therapeutic approaches. All these achievements have shed light on the pathophysiological process of PD and have further explored the comprehensive management of this disease. However, this journey to conquer PD is still far from being accomplished. Early and precise diagnosis strategies, together with disease-modifying therapy, are urgently needed. To this end, it is necessary to recall these milestones in PD research history and appreciate their lasting impact on current and future PD research. In a historical review article published recently in Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Dr. Serge Przedborski recounted the fascinating 200-year journey of PD [1]. To better highlight the historical milestones of PD research, here, we have extracted important discoveries from Dr. Przedborski’s timely review paper. In addition, we also provide important supplementary information to emphasize the significant contributions of research findings from East and West before James Parkinson.

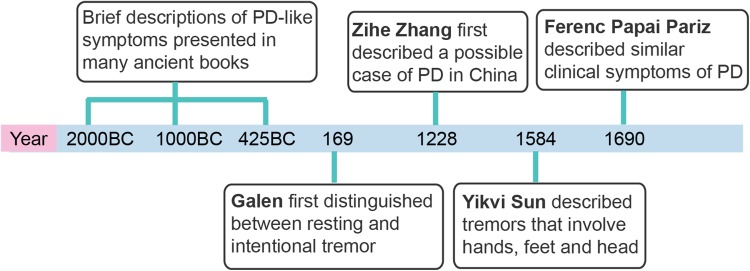

Although PD was named after James Parkinson by Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), considering Parkinson’s first description of the shaking palsy in a monograph entitled “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy”, brief descriptions of PD-like symptoms have been presented in many ancient texts from both the Western and Eastern literatures (Fig. 1), such as the Old Testament of the Bible (2000–440 BC), the Caraka Samhita of Ayurvedic medicine (~1000 BC), and The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine (Huang Di Nei Jing, ~425–221 BC) [2]. Following these brief symptomatic descriptions, Galen (129–200), the famous anatomist and experimental physiologist of ancient Rome, first distinguished two different tremors as resting and intentional in his book ‘‘De Tremore, Palpitatione, Convulsione et Rigore’’ in 169 BC [3]. After Galen’s descriptions of the shaking palsy, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) presented a quite detailed description of the shaking palsy as a combination of difficulty with voluntary movement and tremor [4]. The Hungarian physician, Ferenc Papai Pariz (1649–1716), described the clinical symptoms of PD in a textbook in 1690, more than 120 years earlier than Parkinson [5]. Besides the Western literatures, references can be found in ancient Chinese medical books, including Master Hua’s Classic of the Central Viscera (Zhong Zang Jing) by Tuo Hua (145–208) and General Treatise on Causes and Manifestations of All Diseases (Zhu Bing Yuan Hou Lun) by Yuanfang Chao (550–630) [6]. In addition, Zihe Zhang (1151–1231), a Chinese physician of the Jin-Yuan Dynasty, described some similar disease features including tremor, stiffness, unexpressive facial features, loss of dexterity of finger movements, depression, a chronic progressive course, and a poor response to drugs [6]. Yikvi Sun (1522–1619) in the Ming Dynasty described tremors that involve the hands, feet and head [6].

Fig. 1.

Brief descriptions of Parkinson’s disease-like symptoms before James Parkinson.

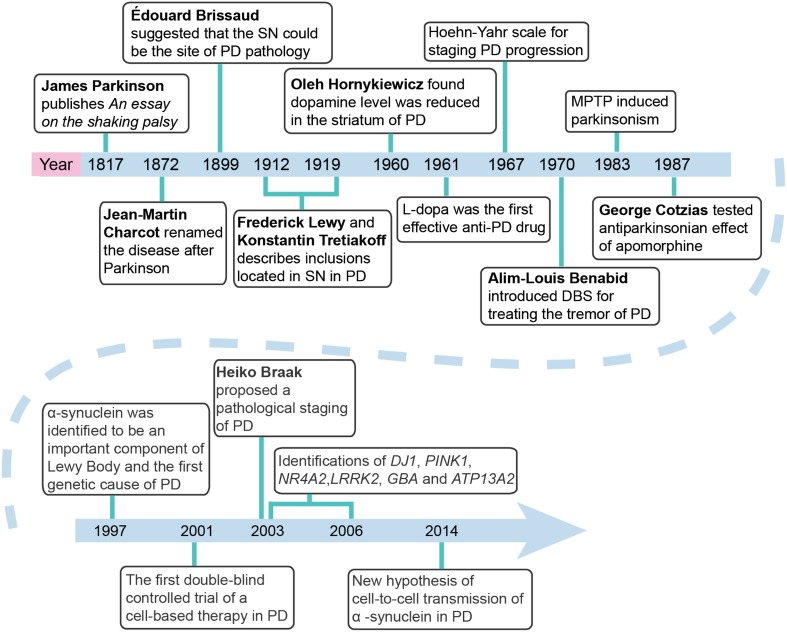

While all the ancient literatures provided general descriptions covering most of the symptoms of PD, achievements in the anatomical, pathological, and neurochemical features of PD were made after 1899. Édouard Brissaud (1852–1909) first suggested in 1899 that PD originated pathologically from the damaged substantia nigra [7]. More importantly, in 1912, Frederick Lewy (1885–1950) observed aggregated inclusions, which were then further revealed to be located inside the substantia nigra and named as Lewy body by Konstantin Tretiakoff (1892–1958) in 1919 [8, 9]. While these pathological observations promoted the understanding of PD, the neurochemical findings provided a better approach for PD therapy. In 1960, Oleh Hornykiewicz (1926–) found reduced dopamine level in the striatum of PD patients [10]. On the basis of this finding, in 1961, levo-dopa (L-dopa), a direct precursor of dopamine, was first noted to be effective in improving PD symptoms via the oral route by André Barbeau (1931–1986) [11]. In 1967, the sustained therapeutic benefits of L-dopa in PD patients were further confirmed in a double-blind placebo-controlled study by Melvin D. Yahr (1917–2004), who introduced the Hoehn-Yahr scale for staging PD progression, and in open-label studies by George Cotzias (1918–1977) who established the combined use of L-dopa with a peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitor. The dopamine receptor agonists bromocriptine and apomorphine were also found to be potent for PD therapy by George Cotzias and Donald Brian Calne (1936–) in the early 1970s [12, 13]. Notably, since the success of bromocriptine, several other dopamine agonists including rotigotine, ropinirole, and pramipexole have been developed and clinically used. Considering the fact that PD is caused by dopamine neuron loss and the consequent dopamine deficiency, focal dopamine delivery systems (using cell-based and viral vector-based therapies) and intracerebral injection and viral vector-based delivery of trophic factors (such as glia cell-derived neurotrophic factor or neurturin) were established to boost the reduced cell viability and dopaminergic action. By the early 1980s, cell suspensions made from fetal ventral mesencephalic tissue had been shown to survive, innervate the host striatum, receive afferent fibers, release dopamine, and restore deficits in PD animal models (reviewed by Brundin [14]). On the basis of these preclinical data, between the 1980s and 1990s, a number of cell-based therapies were conducted in PD patients (reviewed by Barker [15]). From 1982 to 1985, the first clinical trial of a cell-based therapy for humans with PD was made in Lund [16]. In 2001, the first double-blind controlled trial of a cell-based therapy in PD was performed [17]. In 2003, John Nutt (1944–) organized the first randomized, double-blind clinical trial of glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor for the treatment of PD [18]. The transplantation of neural cells, including induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopamine neurons, provides a clear illustration of the kind of technical prowess and innovation that underpins the search for PD treatments without adverse effects. However, several disadvantages of these approaches, such as the insufficient therapeutic efficacy and ethical issues, have significantly limited their wide application.

In 1987, Alim-Louis Benabid (1942–) introduced deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus for controlling PD tremor [19]. DBS was used in the subthalamic nucleus to treat PD in 1995 by Pierre Pollak (1950–) [20] and finally entered clinical applications for the first time in 1998 [21]. DBS suppresses the excessively synchronized oscillation in nuclei of the basal ganglia and reduces the phase-amplitude coupling in the motor cortex, suggesting that the high-frequency current delivered to the subthalamic nucleus or pallidal internal segment by DBS electrodes may produce symptomatic benefits by alleviating a PD-related pathological synchrony. The effectiveness of DBS for PD therapy was recognized by the 2014 Lasker–DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award to Alim Louis Benabid (1942–) and Mahlon R. DeLong (1938–).

Understanding the pathophysiological progress of PD promotes not only the exploration of novel therapeutic strategies, but also disease staging. While the H & Y stages established by Yahr in 1967 [22] are well-accepted, Heiko Braak (1937–) proposes a staging procedure by tracing the course of pathology in incidental and symptomatic PD cases [23].

As for the causal or risk factors, we now note that both environmental and genetic factors are involved in PD pathogenesis. In the early 1980s, William Langston and Irwin J. Kopin (1929–) found that 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced parkinsonism in a group of young drug addicts [24]. This was later confirmed in animal models [25], initiating research on environmental factors in the pathogenesis of PD. In 1997, 85 years after the first observation of Lewy bodies by Frederick Lewy, scientists identified >50 proteins in this aggregated inclusion, α-synuclein being the most important component [26]. Moreover, in the same year, the α-synuclein gene (SNCA) was further identified as the first causal gene of PD by Mihael Polymeropoulos [27]. This finding opened a door to exploring pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic strategies through genetic screening. After SNCA, >20 genes and loci have been found to be related to PD [28]. In 2003, mutations in NR4A2 were found to be associated with familial PD [29]; in 2004, the GBA mutation was identified as a risk factor for PD [30]; in 2010, Parkin–PINK1 interactions were reported to regulate mitophagy [31]; and in 2014, Nalls et al. found that genes that had previously been linked to familial PD, such as SNCA, LRRK2, and VPS13C, were located at the risk loci identified for sporadic PD [32]. Interestingly, despite the cell-autonomous mechanisms of neurodegeneration in PD, recent studies have suggested a unique pathological progression of the disease through non-cell-autonomous mechanisms. Cell-to-cell transmission of α-synuclein via lymphocyte-activation gene 3-related mechanisms [34] has been reported in PD [33]. Moreover, most recent research findings have further demonstrated a possible peripheral to central spread of PD pathology via the vagus, as evidenced by a lower risk among patients with truncal vagotomy [35].

After the first demonstration of dopamine in the brain by Arvid Carlsson (1923–) in 1958, several accomplishments in clinical and preclinical research were also achieved in China. In 1979, Drs Xiaoda Zhou, Xinde Wang, and Delong Xu established a PD outpatient clinic and started to train movement disorder specialists. Prof. Guozhang Jin discovered the dopamine receptor antagonist L-tetrahydropalmatine, and Drs Delong Xu, Shengdi Chen, and Weidong Le established the first MPTP-induced PD animal model in China [36, 37]. In 1997–1998, Dr. Zhenxin Zhang performed a cross-sectional prevalence study and suggested that the prevalence of PD in China is similar to that in developed countries [38]. In 2002, the Chinese Society of Movement Disorders was established. In 2006, Dr. Zhuohua Zhang and his colleagues revealed the association of PINK1 and DJ-1 demonstrating digenic inheritance of early-onset PD [39]. In 2006, the first version of the PD Diagnosis Guideline for China was published (revised and republished in 2016). All these efforts have greatly promoted the progress of PD research in China.

In summary, the rapid progress in our understanding of PD in the past 200 years has been remarkable (Fig. 2). PD research is still advancing rapidly, with hot-spots especially in human studies, such as functional genetics, novel molecular mechanisms, brain-imaging techniques, biomarker detection, and new targeting therapies. Despite major breakthroughs in PD research, we still do not have a cure. The environmental factors in PD pathogenesis deserve further exploration, considering the fact that a combination of environmental and genetic factors may determine who develops the disease. The mechanisms by which PD pathology spreads from cell to cell within circuits of the brain or transmits from peripheral organs to central nervous system should be further explored. Moreover, studies should also be conducted in order to develop early prodromal diagnostic techniques and to understand why diverse pathogenic factors specifically affect dopamine neurons in PD.

Fig. 2.

Milestones of 200 years of Parkinson’s disease research since 1817.

References

- 1.Przedborski S. The two-century journey of Parkinson disease research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raudino F. The Parkinson disease before James Parkinson. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:945–948. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sider D, McVaugh M. Galen on tremor, palpitation, spasm, and rigor. Trans Stud Coll Physicians Phila. 1979;1:183–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calne DB, Dubini A, Stern G. Did Leonardo describe Parkinson’s disease? New Engl J Med. 1989;320:594. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bereczki D. The description of all four cardinal signs of Parkinson’s disease in a Hungarian medical text published in 1690. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Dong Z, Roman GC. Early descriptions of Parkinson disease in Ancient China. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:782–784. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brissaud É. Leçons sur les maladies nerveuses (Deuxième série, Hôpital Saint-Antoine) recueillies et publiées par Henry Meige. Paris: Masson; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forster E, Lewy FH. Paralysis agitans. I. Pathologische Anatomie (von F.H. Lewy). In: Lewandowsky M, Abelsdorff G (Eds.), Handbuch der Neurologie, 3rd Edn. Springer, Berlin 1912: 920–933.

- 9.Tretiakoff C, Contribution à l’étude de l’anatomie pathologique du locus niger de Sommering avec quelques déductions relatives à la pathogénie des troubles du tonus musculaire et de la maladie de Parkinson. Thèse méd. Paris, No. 293, 1919.

- 10.Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system. Klin Wochenschr. 1960;38:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF01485901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbeau A. Biochemistry of Parkinson’s disease. In: Proceedings of the seventh international congress of neurology, Rome, Sept, Societa Grafica Romana, Rome, 1961, 2: 925.

- 12.Cotzias GC, Papavasiliou PS, Fehling C, Kaufman B, Mena I. Similarities between neurologic effects of L-dopa and of apomorphine. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:31–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001012820107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calne DB, Teychenne PF, Claveria LE, Eastman R, Greenacre JK, Petrie A. Bromocriptine in Parkinsonism. Br Med J. 1974;4:442–444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5942.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brundin P, Barker RA, Parmar M. Neural grafting in Parkinson’s disease: problems and possibilities. Prog Brain Res. 2010;184:265–294. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker RA, Drouin-Ouellet J, Parmar M. Cell-based therapies for Parkinson disease—past insights and future potential. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:492–503. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Backlund EO, Granberg PO, Hamberger B, Knutsson E, Mårtensson A, Sedvall G, Seiger A, Olson L. Transplantation of adrenal medullary tissue to striatum in parkinsonism. First clinical trials. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:169–173. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, Tsai WY, DuMouchel W, Kao R, et al. Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:710–719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nutt JG, Burchiel KJ, Comella CL, Jankovic J, Lang AE, Laws ER, Jr, et al. Implanted intracerebroventricular. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Randomized, double-blind trial of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in PD. Neurology. 2003;60:69–73. doi: 10.1212/WNL.60.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benabid AL, Pollak P, Louveau A, Henry S, de Rougemont J. Combined (thalamotomy and stimulation) stereotactic surgery of the VIM thalamic nucleus for bilateral Parkinson disease. Appl Neurophysiol. 1987;50:344–346. doi: 10.1159/000100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limousin P, Pollak P, Benazzouz A, Hoffmann D, Le Bas JF, Broussolle E, et al. Effect of parkinsonian signs and symptoms of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Lancet. 1995;345:91–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar R, Lozano AM, Kim YJ, Hutchison WD, Sime E, Halket E, Lang AE. Double-blind evaluation of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:850–855. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns RS, Chiueh CC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Jacobowitz DM, Kopin IJ. A primate model of parkinsonism: selective destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra by N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6 -tetrahydropyridine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4546–4550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CD, Chan P. Clinicogenetics of Parkinson’s disease: a drawing but not completed picture. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2014;1:115–126. doi: 10.4103/2347-8659.143662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le WD, Xu P, Jankovic J, Jiang H, Appel SH, Smith RG, et al. Mutations in NR4A2 associated with familial Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:85–89. doi: 10.1038/ng1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aharon-Peretz J, Rosenbaum H, Gershoni-Baruch R. Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene and Parkinson’s disease in Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1972–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nalls MA, Pankratz N, Lill CM, Do CB, Hernandez DG, Saad M, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:989–993. doi: 10.1038/ng.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo JL, Lee VM. Cell-to-cell transmission of pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Med. 2014;20:130–138. doi: 10.1038/nm.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao X, Ou MT, Karuppagounder SS, Kam TI, Yin X, Xiong Y, et al. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiated by binding lymphocyte-activation gene 3. Science 2016, 353. pii: aah3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Liu B, Fang F, Pedersen NL, Tillander A, Ludvigsson JF, Ekbom A, et al. Vagotomy and Parkinson disease: A Swedish register-based matched-cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88:1996–2002. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheng JG, Delong Xu. Changes of striatal dopamine induced by MPTP in mice. Acta Universitatis Medicinalis Secondae Shanghai 1987, 7: 153–156.

- 37.Le WD, Zhou XD, Jin GZ, Xu SX. Biochemical changes and rotaing behavior induced by MPTP injection in rat SNc. Chin Sci Bull. 1988;33:786–789. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang ZX, Roman GC, Hong Z, Wu CB, Qu QM, Huang JB, et al. Parkinson’s disease in China: prevalence in Beijing, Xian, and Shanghai. Lancet. 2005;365:595–597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang B, Xiong H, Sun P, Zhang Y, Wang D, Hu Z, et al. Association of PINK1 and DJ-1 confers digenic inheritance of early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1816–1825. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]