Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to explore the role of miR-126 in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients and the potential gene targets of miR-126 in atherosclerosis.

Methodology

A total of 60 CAD patients and 25 healthy control subjects were recruited in this study. Among the 60 CAD patients, 18 cases were diagnosed of stable angina pectoris (SAP), 20 were diagnosed of unstable angina pectoris (UAP) and 22 were diagnosed of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Plasma miR-126 levels from both groups of participants were analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR. ELISA was used to measure plasma level of placenta growth factor (PLGF).

Results

The results showed that the miR-126 expression was significantly down-regulated in the circulation of CAD patients compared with control subjects (P<0.01). Plasma PLGF level was significantly upregulated in patients with unstable angina pectoris and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) compared with controls (both P<0.01) the miR-126 expression in AMI was significantly associated with PLGF.

Conclusion

miR-126 may serve as a novel biomarker for CAD.

Keywords: miR-126, PLGF, PCR, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis

Introduction

Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the most important causes of sudden cardiac death, accounting for more than 80% of the cases worldwide.1,2 Despite recent advances in intervention and medication treatments, CAD is still considered to be a severe health threat with high morbidity and mortality worldwide.3 Further development of diagnosis and treatment based on novel molecular mechanisms are necessary for the further improvement to reduce the mortality of CAD patients.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules of approximately 16–22 nucleotides.4 Recent researches have demonstrated that miRNAs serve as post-transcriptional regulators of various genes expression through specific interaction with certain messenger RNAs (mRNAs) by inducing degradation or repressing translation of the mRNAs.5,6 Recently, many studies have shown that miRNA expression could be a valuable signature for predicting the diagnosis and/or prognosis in patients of cardiovascular diseases or cancer.7,8 In cardiovascular system, miRNAs were observed to be involved in heart and vascular development.9 Thus, it is reasonable to speculate a potential role of miRNA in diagnosis, therapeutic efficacy and prognosis evaluation in patients with CAD. In particular, aberrant expression of miRNA-126 was found in patients with atrial fibrillation, heart failure and CAD10,11, suggesting a regulatory role of miRNA-126 in cardiovascular system. Therefore, we first investigated the role of miR-126 in atherosclerosis/CAD in this study. miR-126 as a positive regulator of several vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family members including PLGF. Then, we studied the plasma level of placental growth factor (PLGF) as well as its correlation with miR-126.

Methods

Characteristics of patients

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Affiliated Heping Hospital of Changzhi Medical College, Changzhi, China. Written informed consent for the clinical study was obtained from all of the patients. A total of 60 CAD patients diagnosed in our hospital between June 2015 and March 2016, were selected. 25 normal healthy people were gathered from the medical examination center of our hospital as the control group. Among the 60 CAD patients, 18 cases were diagnosed of stable angina pectoris (SAP), 20 were diagnosed of unstable angina pectoris (UAP) and 22 were diagnosed of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Patients in CAD group were significantly older compared with control groups (p<0.05). Besides, CAD group had a significantly increased percentage of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and smoking compared with controls (all p<0.05). High incidence of both high and intermediate syntax scores were observed in CAD group. Diagnosis of SAP and UAP were based on typical chest pain. Diagnosis of AMI was based on either of the several indexes listed below, including (1) ischemic symptoms; (2) increased levels of troponin and creatine kinase to >2 times the upper limit of normal; (3) ST-segment abnormality; and (4) pathological Q wave12. Coronary angiography was used to confirm CAD and define the severity of coronary artery lesions. Blood samples from each participant in both second and third cohorts were obtained immediately after admission, and plasma was stored at −80°C.

The Syntax score and angiographic analysis

Each coronary lesion with ≥ 50% diameter narrowing in vessels (≥ 1.5 mm) was calculated according to the baseline diagnostic angiogram. The Syntax score algorithm was performed to calculate the overall Syntax score. Two experienced interventional cardiologists determined the Syntax score of each patient blindly and independently. The final reported value was determined by the average value of the two cardiologists.

Isolation of total RNA and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

The plasma level of miR-126 was quantified by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated by a RNAprep pure Blood Kit from Tiangen Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China), followed by a reverse transcription using a QuantScript RT Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) to synthesize the first strand of complementary DNA (cDNA). cDNAs were then subjected to RT-PCR amplification using a 7500 Fast RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). TaqMan gene expression assay kit for miR-126 (catalog number 000397) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). The relative expression level of miR-126 was determined by 2-ΔΔCT method.

PLGF measurement

Level of plasma PLGF was performed by high sensitivity indirect sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Reading of optical density was set at 450 nm and normalized to 570 nm according to the instruction by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

Data was reported as either means (standard deviation, SD). T test was used when comparing the difference between two groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when more than two groups were involved in the statistic analysis. The categorical variables were compared using χ2 test. Correlations between miR-126 and PLGF as well as other biochemical parameters were performed with Pearson correlation analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients in CAD group were significantly older compared with control groups (p<0.05). Besides, CAD group had a significantly increased percentage of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and smoking compared with controls (all p<0.05). High incidence of both high and intermediate syntax scores were observed in CAD group. A sub-group analysis of CAD patients showed significantly difference in population characteristics among SAP, UAP and AMI sub-groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics.

| Characteristic | Control (n=25) |

CAD (n=60) | CAD subpopulation | ||

| SAP | UAP | AMI | |||

| [n, (%)] | 11(44) | 45(75) | 18(30) | 20(33.3) | 22(36.7) |

| Age (year) | 52.8(13.3) | 62.1(15.4) * | 61.3(12.4) | 63.2(11.8) | 62.4(14.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) |

5(20) | 7(11.7) * | 2(3.33) | 2(3.33) | 3(5) |

| Hypertension (%) |

7(28) | 44(73.3) * | 14(23.3) | 15(25) | 15(25) |

| Current smoker n (%) |

8(32) | 41(68.3) * | 13(21.7) | 13(21.7) | 15(25) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) |

4.13(0.82) | 4.06(0.98) | 4.02(0.88) | 4.08(0.82) | 4.12(1.02) |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) |

2.17(0.41) | 2.46(0.81) | 2.38(0.66) | 2.47(0.58) | 2.47(0.84) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) |

1.14(0.31) | 1.16(0.33) | 1.20(0.25) | 1.17(0.34) | 1.04(0.32) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) |

1.92(0.55) | 1.61(0.77) | 1.72(0.69) | 1.55(0.78) | 1.60(0.72) |

| Glucose (mmol/L) |

5.12(1.41) | 6.77(2.49) | 5.68(1.84) | 6.86(2.38) | 6.41(2.52) |

| Ejection fraction (%) |

74.1(7.6) | 73.1(6.5) | 74.2(7.6) | 70.6(6.2) | 65.8(6.4) |

| Syntax score | |||||

| Low (0-22) [n, (%)] |

25(100) | 53(88.3) | 13(21.7) | 18(30) | 22(36.7) |

| Intermediate (23–32) [n, (%)] |

0(0) | 3(5) | 0(0) | 1(1.67) | 2(3.33) |

| High (33 or more) [n, (%)] |

0(0) | 4(6.7) | 0(0) | 2(3.33) | 2(3.33) |

CAD: coronary artery disease patients; LDL-C: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

p<0.05 between control and CAD groups

MiR-126 was significantly down-regulated in CAD patients.

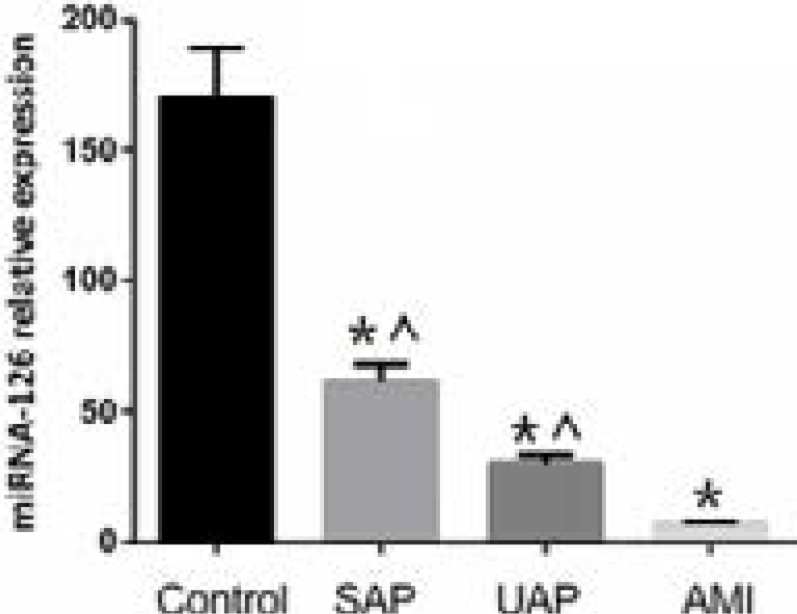

Circulating miR-126 level in CAD group (including SAP, UAP and AMI subgroups) was significantly lower than that in the control group (30 ± 12 in CAD group vs. 150 ± 32 in control group, p<0.01, Figure 1). Besides, circulating miR-126 level was the lowest in AMI compared with SAP and UAP groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Circulating miR-126 levels in controls and CAD sub-groups. miR-126 was down regulated in CAD patients. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CAD: coronary artery disease patients; SAP: stable angina pectoris; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.* p<0.05 vs. control. ^ p<0.05 vs. AMI.

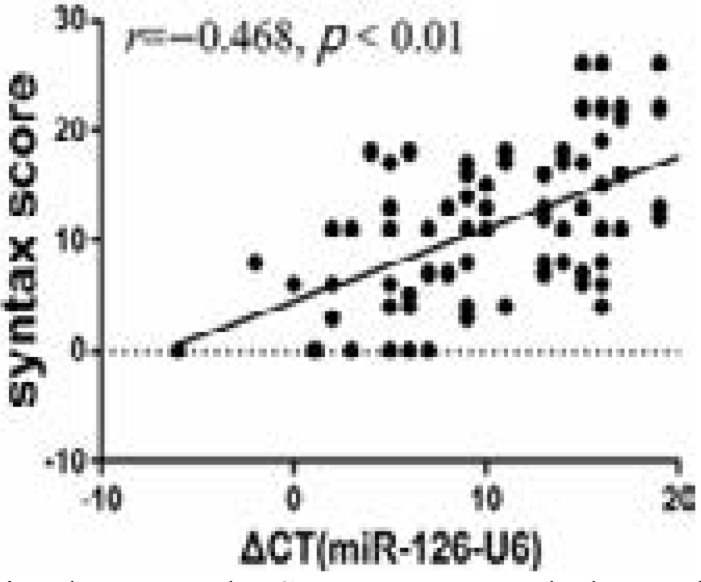

The syntax score was associated with plasma miR-126 level in this cohort (r = −0.468, P < 0.01, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation between the Syntax score and plasma level of miR-126.

Plasma PLGF level in CAD patients and its correlation with miR-126

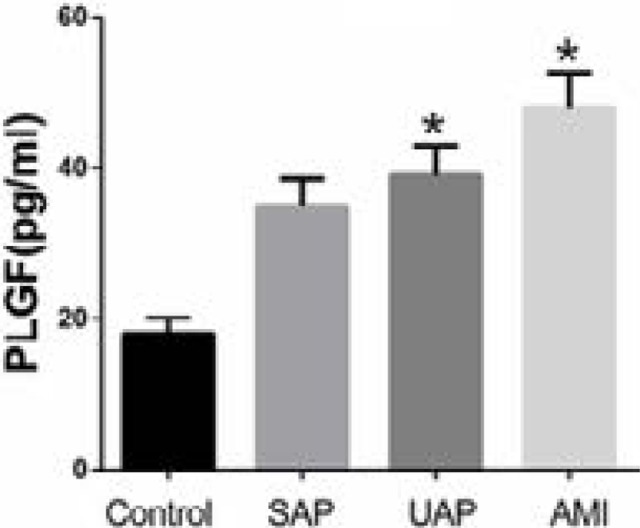

Plasma PLGF level was significantly higher in UAP and AMI compared with the control group (both p<0.01). However, patients with SAP showed no difference with the control group (p>0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plasma levels of PLGF in CAD patients and controls. * p<0.01 UAP vs. control and AMI vs. control. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CAD: coronary artery disease patients; PLGF: placental growth factor; SAP: stable angina pectoris; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

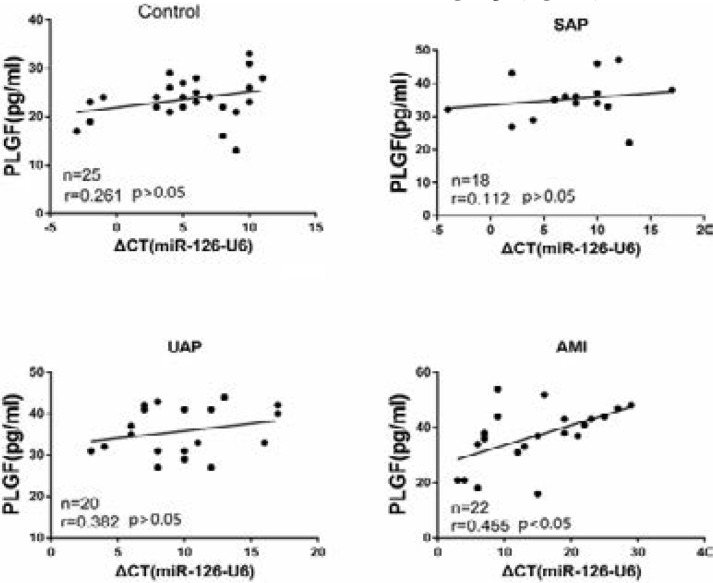

Furthermore, miR-126 level was associated with plasma PLGF level in AMI group (r=0.455, p<0.05), but not in other sub-groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between PLGF and miR-126 in CAD patients. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CAD: coronary artery disease patients; NS: no significant; PLGF: placental growth factor; SAP: stable angina pectoris; UAP: unstable angina pectoris.

Discussion

CAD is caused by atherosclerotic lesion which ultimately narrows the vessel lumen, causing the ischemic symptoms and cardiac dysfunction. CAD has been one of the major health problems worldwide despite the advances in treatments.13,14 Thus, there is a crucial need to find new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for CAD to further improve the prognosis of these patients. Circulating miRNAs may be proposed by various clinical studies as prognostic biomarkers for CAD.15 For instance, one study showed that miR-133 and miR-208a were up-regulated in CAD patients compared to controls.16 Furthermore, The miRNA array analyses of various human tissues have indicated that miR-499 was produced almost exclusively in the heart and plasma concentration of miR-499 may be a useful biomarker of myocardial infarction in humans.17 Moreover, accumulating evidence has suggested the usefulness of circulating miRNAs as stable blood-based biomarkers for various diseases.18,19 Therefore, all those studies have pointed out that miRNA may be used as biomarker or even therapeutic targets for CAD.

MiRNA-126 is a short non-coding RNA that is derived from the (EGF Like Domain Multiple 7 (EGFL7) gene.20 miR-126 is highly expressed in heart, liver, and lungs,21,22 which was associated with activation of the vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway in the endothelium. Those results indicated that miR-126 might have played a beneficial role in CAD.

Our results showed that miR-126 was down-regulated in patients with CAD. Furthermore, the severity of CAD was associated with the expression level of miR-126 in circulation. Therefore, our finding not only suggested a potential role of miR-126 as a biomarker for CAD, but also indicated miR-126 as a useful marker for follow-up of the CAD development in these patients. Moreover, we found that the decreased miR-126 in CAD was associated with increased plasma PLGF level and the two parameters inversely regulated with each other in AMI subgroups, which had more severe CAD and experienced more acute events. Although several studies have reported the increased plasma PLGF levels in CAD patients, we firstly, reported the association between increased PLGF level and unstable CAD including UAP and AMI in this study. More interestingly, we found a significant correlation between plasma miR-126 level and PLGF level, particularly in AMI. All these findings pointed to the possibility that unstable plaque in coronary artery could be featured by decreased miR-126 and increased PLGF. PLGF is an important protein in angiogenesis and has been proposed as a novel therapeutic target for angiogenic disorders. In addition, angiogenesis is one of the major mechanisms in atherosclerosis development. Therefore, this study unraveled a mechanistic possibility of atherosclerosis development related to miR-126, and further studies are urgently needed.

Limitations

However, there are still several limitations in this study. First of all, the sample should be increased to enhance the power of the statistical analysis. Secondly, the findings of this study only suggested an association between miR-126 and CAD and/or PLGF. Mechanistic studies are needed to establish and causational among these three factors.

In this study, we found that circulating miR-126 level was significantly lower in patients with CAD and miR-126 level correlated with severity of CAD. Decreased miR-126 level was associated with increased plasma PLGF levels and a correlation existed between miR-126 and PLGF in AMI patients. Our data suggested miR-126 might be served as a potential marker for both CAD and severity of CAD.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors' contribution:

Guarantor of integrity of the entire study: Yajun lian.

Study concepts: Yajun lian.

Study design: Xiaoyan wang.

Literature research: Xin wen.

Clinical studies: Jing guo, sheng jiang.

Experimental studies: Jing guo, sheng jiang.

Data acquisition: Yaodong hu.

Data analysis: Xiaoyan wang.

Statistical analysis: Yaodong hu.

Manuscript preparation: Xiaoyan wang.

Manuscript editing: Zhiping wang.

Manuscript review: Yajun lian.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Wang HW, Huang TS, Lo HH, Huang PH, Lin CC, Chang SJ, et al. Deficiency of the microRNA-31-microR NA-720 pathway in the plasma and endothelial progenitor cells from patients with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(4):857–869. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollati V, Angelici L, Rizzo G, Pergoli L, Rota F, Hoxha M, et al. Microvesicle-associated microRNA expression is altered upon particulate matter exposure in healthy workers and in A549 cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2015;35(1):59–67. doi: 10.1002/jat.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortez MA, Bueso-Ramos C, Ferdin J, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Calin GA. MicroRNAs in body fluids--the mix of hormones and biomarkers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(8):467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zamore PD, Haley B. Ribo-gnome: the big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309(5740):1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattick JS, Makunin IV. Non-coding RNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:R17–R29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pang C, Guan Y, Zhao K, Chen L, Bao Y, Cui R, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-15b correlates with unfavorable prognosis and malignant progression of human glioma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(5):4943–4952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Chen X, Huang J, Sun Q, Wang L. Clinical impact of circulating miR-26a,miR-191, and miR-208b in plasma of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:58. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0148-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Mil A, Grundmann S, Goumans MJ, Lei Z, Oerlemans MI, Jaksani S, et al. MicroRNA-214 inhibits angiogenesis by targeting Quaking and reducing angiogenic growth factor release. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93(4):655–665. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun X, Zhang M, Sanagawa A, Mori C, Ito S, Iwaki S, et al. Circulating microRNA-126 in patients with coronary artery disease: correlation with LDL cholesterol. Thromb J. 2012;10(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei XJ, Han M, Yang FY, Wei GC, Liang ZG, Yao H, et al. Biological significance of miR-126 expression in a trial fibrillation and heart failure. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48(11):983–989. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20154590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Storrow AB, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry: National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2007;115(13):e356–e375. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelhardt S. Small RNA biomarkers come of age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(4):300–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM, Creemers EE. Circulating microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(9):H1085–H1095. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00191.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fichtlscherer S, De Rosa S, Fox H, Schwietz T, Fischer A, Liebetrau C, et al. Circulating microRNAs in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2010;107(5):677–684. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bostjancic E, Zidar N, Stajer D, Glavac D. MicroRNAs miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b and miR-208 are dysregulated in human myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2010;115(3):163–169. doi: 10.1159/000268088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Zhang L, Su T, Li H, Huang Q, Wu D, et al. Kinetics of plasma microRNA-499 expression in acute myocardial infarction. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(5):890–896. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.11.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18(10):997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chim SS, Shing TK, Hung EC, Leung TY, Lau TK, Chiu RW, et al. Detection and characterization of placental microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 2008;54(3):482–490. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musiyenko A, Bitko V, Barik S. Ectopic expression of miR-126, an intronic product of the vascular endothelial EGF-like 7 gene, regulates prostein translation and invasiveness of prostate cancer LNCaP cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008;86(3):313–322. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0296-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh RF, Wythe JD, et al. miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell. 2008;15(2):272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]