Abstract

Background

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) typically defines communities by geography, ethnicity, shared health needs, or some combination.

Objectives

We describe a CBPR project aiming to engage diverse minority and underserved communities throughout Michigan in deliberations about health research priorities.

Methods

A Steering Committee (SC) with 15 members from minority and underserved communities, and 4 members from research organizations led the project, with the help of regional advisory groups (RAGs) formed at the SC’s request. Evaluation of the SC used questionnaires, focused group discussion, and review of SC meetings to describe engagement, partnership, and communication.

Lessons Learned

An academic-community partnership with a diverse, dispersed and broadly defined community found value in RAGs, dedicated academic staff, face-to-face meetings, varied communication modalities, capacity building tailored to varying levels of CBPR experience, and ongoing evaluation.

Conclusions

A geographically and culturally diverse partnership presents challenges and opportunities in representativeness, relationship building, capacity building, and communication.

Keywords: Community health partnerships; Community-Based Participatory Research, Community health research; Community-Based Participatory Research, Health disparities; Community-Based Participatory Research, Process issues; Community-Based Participatory Research, Great Lakes Region; United States; North America; Americas; Geographic Locations, Health Priorities; Delivery of Health Care; Health Care Quality, Access, and Evaluation; Health Care, Program Evaluation; Health Care Evaluation Mechanisms; Quality of Health Care; Health Care Quality, Access, and Evaluation; Health Care

INTRODUCTION

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) emphasizes “the participation and influence of nonacademic researchers in the process of creating knowledge,”1 including identifying research needs and priorities. We describe a 5-year CBPR project aiming to engage minority and underserved communities throughout the state of Michigan in deliberations about health research priorities to increase community voice in how limited health research resources are allocated. The DECIDERS project (Deliberative Engagement of Communities in DEcisions about Research Spending) formed a state-wide Steering Committee (SC) to develop a new version of the deliberative exercise CHAT,2,3 then convened 47 focus groups to test the tool and engage communities in setting health research priorities.4

The shared identity of being minority and/or medically underserved, and often having little voice in policy making, could unite diverse communities and community partners behind the aim of increasing their voices in health research priority setting. The project’s goal could be undermined if only some voices were included, since fair allocation of resources requires considering the needs, preferences and values of all those who could be affected by allocation decisions. Collective engagement might also strengthen the sense of statewide community.1 However, blending different communities of identity into a single, statewide project posed challenges. Here we present our process and lessons learned from a statewide CBPR partnership involving many community partners.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Partnership Documentation and Evaluation

We conducted formative and developmental evaluation of the DECIDERS partnership. Participatory evaluation5 was led by an external evaluator and a workgroup composed of four SC members, the co-directors, and the project manager, who were involved in all aspects of design, analysis, interpretation, and feedback to the full SC. Mixed methods6 included data collected from:

Project documentation (e.g., meeting minutes, decisions, attendance, SC member participation in activities);

Periodic closed-ended survey to assess CBPR process and effectiveness (e.g., participation, trust, group dynamics, communication, satisfaction);

Semi-structured focused evaluation discussions with the SC and home team; and

Direct observations by an external evaluator.

The survey, based on an existing conceptual framework and instrument,7 was adapted to evaluate a statewide partnership (e.g., additions regarding communication, representation). Results are from the first survey, completed online by 14 of 16 active SC members and 4 home team members (co-directors and staff). Descriptive statistics were calculated separately for SC and home team members. Data from open-ended questions were themed using an inductive approach. Findings from quantitative and qualitative data were integrated to enhance understanding, and key quotes illustrate findings.

Program evaluation activities like those reported here are not defined as human subjects research and therefore do not require IRB approval.8

Structure of the Partnership

Existing community-academic partnerships provided the foundation for the project and its conceptualization. The project has been led by community and academic co-directors. Mr. Rowe, a founding Board member of the Detroit Urban Research Center, has longstanding and deep ties with many community-based organizations in Michigan, and expertise and experience in CBPR. Dr. Goold brings expertise in social science research and public deliberation about health policy. Other researchers brought expertise in deliberation, public engagement in research, and social science research methods. Research staff at the university had experience and expertise in CBPR and social science research.

A Steering Committee assembled by the co-directors to direct the project included 15 members from minority and underserved communities throughout Michigan, and 4 members from organizations that fund and/or conduct health research in the state. We aimed for representation from all regions of the state and a wide range of experiences and perspectives, while keeping the size of the committee small enough (less than 20) for high-quality dialogue and decision-making.9 The rationale for involving many, varied underserved communities included acknowledging that health research priorities, like health priorities, could be quite different for rural than for urban communities, Native American compared to African-American communities, and established Hispanic/Latino communities compared to migrant farm worker communities, for example. Deliberation about tradeoffs between competing needs for limited resources should, to enhance fairness, include consideration of diverse needs. We sought a variety of communities and welcomed identification of varied health and health research needs. Our communities were geographically dispersed, culturally diverse and without a unifying health need.

Since the project aimed to develop and test a method for engaging communities in deliberations about health research priorities, we needed community members with some understanding of and experience with health research. Some SC members had served as partners on CBPR projects for years, but in many regions we found it challenging to identify and engage community leaders with CBPR or health research experience and with time available for the project.. Hence, a few SC members represented health care or public health institutions rather than community-based organizations. These members also had experience leading or consulting with community advisory groups.

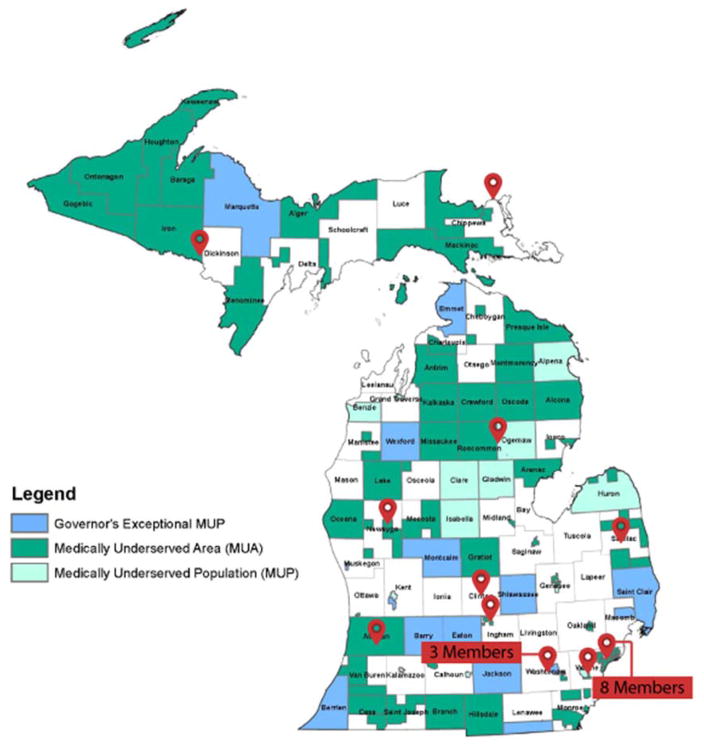

We aspired to find individuals from socially rooted organizations. These individuals have a defined constituency to whom they are accountable, and existing groups’ organizing capabilities can increase the political power of individuals and bring knowledge and flexibility to decision-making. We aimed to find community leaders in or near medically underserved counties and populations (See Figure 1). Co-directors met with each prospective member in person or (for distant members) by phone to describe the project, answer questions, and discover their interest in and ability to serve on the SC. SC community members included, at the start, 10 women and 5 men, and at least one member identified with each of the racial and ethnic groups in Table 1. SC members brought knowledge and experience related to chronic illness, mental illness, AIDS, and public health, among others. Four members of the original SC have resigned and been replaced by similarly qualified, SC approved, community leaders.

Figure 1. Medically Underserved Area/Population (MUA/P) Designations in Michigan.10.

Each marker indicates the location of (a) SC member(s).

Table 1.

Data on race and ethnicity in Michigan from U.S. Census Bureau.11

| % | |

|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 77% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14% |

| Hispanic | 4% |

| Asian | 2.4% |

| Arab American/Chaldean | 2% |

| Native American | 1% |

| Pacific Islander | <1% |

Members of the SC from health research institutions provided advice about successfully communicating public input to decision-makers, and aimed to help the project have concrete impact. Community members constituted over two-thirds of the SC to ensure decisions reflect community needs.

Steering Committee Decision-Making and Participation

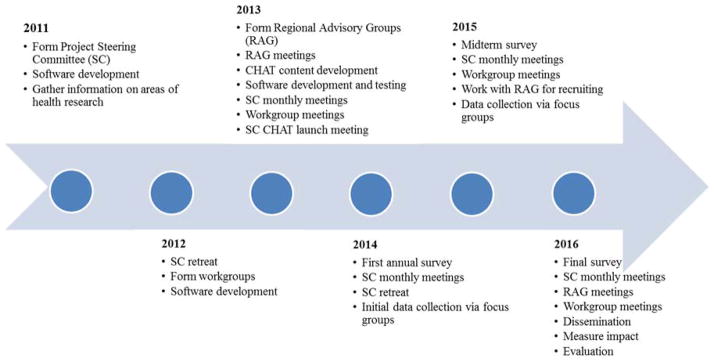

Given the importance of face-to-face contact for relationships and the need to have norms and expectations in place, co-directors and staff were charged by the SC to organize a day-long retreat. (See Fig. 2 Timeline) That meeting began with introductions of the research team, after which all attending were asked to pair off, identify on a Michigan map where the other person lived, and prepare to introduce that person to the group. All were asked to share an important health issue facing their communities, and how research might affect that issue. Since some members of the SC had little experience with or knowledge about CBPR, Mr. Rowe presented guiding principles of CBPR, and led a discussion about the principles the SC deemed most important to follow. We asked the SC to review drafted group norms and expectations and decide which to adopt or revise.

Figure 2.

DECIDERS Project Timeline.

The SC’s first decision, proposed by a member and unanimously adopted, was defining “community” as the state of Michigan, later limited to minority and underserved communities. Discussion referred to communities’ lack of voice in health research priority setting (and other health policy decisions), and a common purpose of enhancing the voice of their communities. They proposed that SC members represent geographic regions (Upper Peninsula, Northeast, Northwest, Thumb, Southeast, Southwest) of the state to “pool our knowledge.” In discussion about the composition of the SC, they identified a need for more local voice and input to help them guide the project, given the size and heterogeneity of the community they had defined. This led to a plan to assemble “regional advisory groups” and development of a list of stakeholders to invite to those groups. SC members helped plan and lead Regional Advisory Group (RAG) meetings held once or twice a year. RAGs reviewed project material (e.g., drafts of the priority setting exercise) and their feedback was brought to SC meetings. The SC further identified a need to engage tribes; co-directors met with tribal health ministers about the project, but decisions to collaborate must be made by tribal leadership.

The “home team” (co-directors, project manager and staff) suggested, and the SC agreed, to form workgroups for various tasks, such as community engagement and dissemination. Nine SC members participated in a workgroup. (See Table 2) Each workgroup included between one and five SC members.

Table 2.

Steering Committee Participation.

| Self-Reported from Survey (N=14) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Reviewed or provided feedback on project materials | 11 | 79 |

| Organized or contacted participants for a Regional Group meeting | 10 | 71 |

| Participated on a work group | 9 | 64 |

| Discussed DECIDERS with outside groups | 7 | 50 |

| Documented from Meeting Records (Oct 2012-August 2014) | ||

| Attendance at Steering Committee webinars* | 49% | |

| Reviewed or provided feedback on project materials** | 20 | 100 |

| Organized or contacted participants for a Regional Group meeting** | 17 | 85 |

| Participated on a work group**: | 9 | 45 |

| CHAT Content | 4 | |

| Community Engagement/Outreach | 3 | |

| Dissemination | 5 | |

| Evaluation | 1 | |

| Software Development | 1 | |

| Steering Committee Evaluation | 3 | |

| Logic Model | 3 | |

Data for the first four items in this table were collected via a survey administered to Steering Committee members by an independent evaluator. The data for the remaining items in this table were compiled from meeting and project records.

There were 20 unique individuals who were SC members at any time over the course of the project.

The retreat included interactive learning about health research and priorities, and the SC began brainstorming about the project. Preferences for communication modalities were discussed, such as use of technology to minimize travel and communicating information through multiple means, including email, website, telephone, web- and telephone-based video meetings, “hard copy” transmission of important documents, and some face-to-face meetings. Members from remote areas were particularly interested in electronic communication. Accordingly, monthly webinars were preceded by dissemination of material in multiple modes, a website provides both public information and password-protected content, and the project manager and other staff have been readily available by phone, email or in-person. In-person meetings have included yearly day-long retreats, workgroup meetings, and attendance at RAGs by researchers and by SC members within a reasonable distance.

Attendance at monthly online webinars averaged 49%, with SC members attending an average of 8.5 meetings (median=10) out of 19 possible (four SC members were not members for all 19). Some members join online (e.g., comments typed during discussions) and some join by telephone, with electronic or hard copies of materials at hand. A majority of Steering Committee members participated in the project in other ways as well (Table 2). The survey identified that SC members understood their own roles and responsibilities well (Table 3).

Table 3.

Steering Committee Understanding of Roles and Responsibilities

| I understand… | Mean (1 = Not at all 2 = A little 3 = Some 4 = Much 5 = A lot) |

|---|---|

| My role in DECIDERS | 4.3 |

| My responsibilities in DECIDERS | 4.2 |

| The roles and responsibilities of: | |

| Regional Groups | 4.3 |

| Work Groups | 4.2 |

| Home Team | 4.1 |

| Research Team | 3.6 |

Data for the items in this table were collected via a survey administered to Steering Committee members by an independent evaluator. The numbers represent the mean responses, with 1= Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Some, 4 = Much, 5 = A lot. (N=14)

LESSONS LEARNED – Challenges, Opportunities and Recommendations

While none of the domains of challenges and opportunities for CBPR we describe - representativeness, capacity, relationships and communication - are novel, we describe particular lessons learned from a statewide CBPR partnership involving many community partners.

Representativeness

Although many community-academic partnerships confront issues about representation, the size and heterogeneity of the community selected by the SC created an unusually important challenge. In CBPR, defining “the community” constitutes an essential early step; the SC defined its community unanimously at the first retreat. Communities may be defined by shared social ties, shared experiences or interests, joint action, and/or a shared locus (place).12–15 Sometimes communities share a health need (e.g., statewide cancer community networks).16 In DECIDERS, the SC recognized a shared vision of increasing voice for minority and underserved communities in health research priority setting.

Representation in decision-making often refers to demographic representation, i.e., whether members of different communities have equal chance to participate in decision-making. However, representation of perspectives addresses whether those most affected by the issue have a fair hearing. Relying on demographic representation as a proxy for perspective representation means relying on assumptions about what perspectives different groups bring.17,18 The SC recognized the multiple and diverse communities in the state, discussed different cultures, and who they themselves represented. They used this knowledge to identify missing perspectives and crafted the RAGs to include other voices. In the evaluation, SC members generally agreed that appropriate members were around the table (mean of 4.4 on a 5-point scale with 1=Strongly Disagree and 5=Strongly Agree), the SC adequately represents state diversity (4.1), and RAGs bring voices that would not otherwise be heard (4.6).

Bringing diverse community leaders together presented opportunities along with challenges. Community leaders from underserved rural areas learned about the health needs of urban underserved communities, and vice versa. Leaders from organizations serving particular racial or ethnic groups (e.g., the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation) learned about each other’s communities’ needs and values. Leaders of scientific and funding organizations learned from community leaders, and community leaders learned about research organizations.

The SC identified a need for representation of tribes, which are important medically underserved communities in Michigan. Since tribes each have their own sovereignty, respectful engagement and partnership require a more involved approach.19

Capacity and Capacity Building

The mix of community members with varying levels of experience with research and leaders of health research institutions had the potential to create imbalances of power. Thus, project staff helped those new to health research partnerships navigate institutional obstacles such as invoicing, subcontracting, and requirements for involvement in human subjects research. Assuring that a supermajority of SC members represented communities, rather than research institutions, also helped ameliorate that imbalance. Each member brought important capacities to the partnership and enabled the creation of new relationships. For example, those with less health research experience brought perspectives of distant and diverse communities (e.g., rural Northern Michigan). These relationships bore fruit beyond the project both informally (e.g., advice from one community leader to another) and formally (e.g., some community leaders were asked by a research institution leader to join a grant proposal). The SC recognized the novelty of the relationships and expressed a need to evaluate not just the project, but the partnership.

The SC and RAGs present an opportunity to develop into a statewide network of minority and underserved communities to collaborate as equal partners with health researchers. Many communities characterized as “medically underserved” are also underserved by health researchers. Such communities expressed surprise (“You came over the bridge!”)(notes from RAG meeting) and often great interest in collaborating with researchers. Community leaders new to CBPR have enhanced their own and community capacity for research by helping to form and lead RAGs. Several members of the SC received training in facilitation and served as facilitators (in English and Spanish) for project data collection.

Building long-distance relationships

Successful CBPR projects build upon existing relationships and efforts within the community,20,4 as did ours. Evidence and advice about building relationships also suggest that face-to-face contact is essential11 and that relationships benefit from activities outside of work.21 For a statewide project, however, face-to-face meetings are time-consuming, inconvenient and burdensome for community partners. Compensation tied to work, but not travel time, adds to the burden. In this case, the SC asked for multiple communication methods, including face-to-face. Importantly, the project manager’s availability and advocacy helped build trust. Since it was rarely feasible to gather solely for nonwork activities, we maximized gathering for meals and breaks during face-to-face meetings and included team-building exercises during retreats.

Some members of the SC knew each other before the project, usually due to their roles and leadership in CBPR. The statewide nature of the project, however, allowed leaders to learn about and connect with similar communities elsewhere in the state; it enabled newer, less experienced leaders or organizations to learn from more experienced colleagues about navigating the frequent challenges of CBOs.

Communication

Despite the challenge of long-distance communication, the SC has coalesced well, as demonstrated by their participation in multiple ways (Table 2). Given the need for open, honest communication and shared power in decision-making, and recognizing the burdens of face-to-face meetings, alternative means for communication were needed.22 SC members voiced preferences for different methods for communicating depending on the purpose of the communication. Based on survey findings, 83% said SC webinars were an effective means to share new ideas and make important decisions. While technology can help strengthen communication, we found face-to-face meetings of the SC essential at least once per year for in-depth discussion of important decisions. We also found smaller face-to-face meetings (workgroups, RAGs) and informal, nonworking time helped develop strong relationships. Others with dispersed community partners have found multiple modes of communication useful, and they also highlight the value of face-to-face meetings and visits to communities.23,24

CONCLUSIONS

In a project which aims to develop and test a method to engage communities in deliberations about research priorities, a network of minority and underserved communities partnered with an academic institution to create a state-wide community. This dispersed and heterogeneous community presented challenges and opportunities and we present the lessons learned about how to promote a well-functioning academic-community partnership that is statewide; that includes geographically, racially, and culturally diverse communities; and that was created for the unusual task at hand. Given the unique nature and aim of the partnership, it necessarily evolved as the project progressed. Some noteworthy features of the process include:

Representativeness - For a project defining a state as the community, even one limited to minority and underserved communities, the population is large and heterogeneous. Regional advisory groups that include a wider variety of stakeholders can provide important input for Steering Committee decisions to reflect diverse communities. To include Native American tribes, communication with those sovereign nations must begin earlier than with other minority communities and accommodate tribes’ approval processes.

Building long-distance relationships - Face-to-face meetings are essential for building relationships and capacity, and for effective dialogue. For geographically dispersed and diverse partners, day-long retreats held every year or so present a more feasible option than more frequent face-to-face meetings, and provide time for in-depth discussion. They also provide some social time that helps build relationships. Staff and researchers attending meetings in local communities also help build relationships.

Communication - Staff and project management must be skilled communicators, reliable and accessible contacts, and experienced facilitators of academic-community partnerships. Researchers (and budgets) must be open to multiple, flexible and accessible modalities. Webinars allow some to join both by phone and online, while others, sent materials ahead of time, can participate by phone only. Face-to-face meetings of workgroups help accomplish essential tasks.

Capacity and Capacity Building - Building capacity for community partners needs to be tailored to partners’ experience and needs, for instance learning about CBPR principles for those new to CBPR, training in facilitation for those with more experience.

Evaluation of the partnership should itself be participatory, and consider a special focus on communication, participation and representation. Budgets should plan to support such evaluation, as well as face-to-face meetings, sufficient compensation for community partners’ time, and multiple modes of communication.

Starting with the identification of health research priorities of minority and underserved communities in Michigan, we hope to continue to strengthen our relationships, build capacity for CBPR throughout the state, and connect community-identified priorities with researchers capable of engaging equitably and competently with community partners to meet their needs.

Contributor Information

Susan Dorr Goold, University of Michigan, General Medicine.

Zachary Rowe, Friends of Parkside.

Lisa Szymecko, University of Michigan, General Medicine and CBSSM.

Chris Coombe, University of Michigan, Health Behavior and Health Education.

Marion Danis, National Institutes of Health-Clinical Center, Clinical, Bioethics.

Adnan Hammad, ACCESS.

Karen Calhoun, City Connect Detroit and Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research.

Cengiz Salman, University of Michigan, General Medicine and CBSSM, Campbell, Terrence; YOUR Center.

References

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998 May;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goold SD, Biddle AK, Klipp G, Hall C, Danis M. “Choosing Healthplans All Together” A Deliberative Exercise for Allocating Limited Health Care Resources. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 2005 Aug;30(4) doi: 10.1215/03616878-30-4-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danis M, Ginsburg M, Goold S. Experience in the United States with public deliberation about health insurance benefits using the small group decision exercise, CHAT. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010 Jul-Sep;33(3):205–14. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181e56340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Accessed December 1, 2015];DECIDERS Project Website. http://www.decidersproject.org. Updated November 2015.

- 5.Coombe CM. Participatory evaluation and other approaches for evaluating community engagement and coalition building. In: Minkler M, editor. Community organizing and community building for health and welfare. 3. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; pp. 346–370. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112–133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel BA, Lantz PM, McGranaghan RJ, Guzmán JR, Lichtenstein R, Rowe Z. Documentation and evaluation of CBPR partnerships: The use of in-depth interviews and close-ended questionnaires. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. pp. 369–397. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Protection of Human Subjects (Common Rule), 45 CFR Parts 46 and 102, Subparts D and F (1991).

- 9.D’Alonzo KT. Getting started in CBPR: lessons in building community partnerships for new researchers. Nursing Inquiry. 2010;17(4):282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources & Service Administration. http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov. Updated June 14, 2012.

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed December 1, 2015];Michigan QuickFacts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/26000.html.

- 12.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scotti R, et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–38. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, McGranaghan R, Allen A, Guzman R, et al. The Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center: lessons learned in the development, implementation and evaluation of a community-based participatory research partnership. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001;7(5):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagel J. American Indian ethnic renewal: politics and resurgence of identity. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60(6):947–965. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peroff NC, Wildcat DR. Who is an American Indian? Soc Sci J. 2002;39(3):349–361. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun KL, Nguyen TT, Tanjasiri SP, Campbell J, Heiney SP, Brandt HM, et al. Operationalization of community-based participatory research principles: assessment of the National Cancer Institute’s Community Network Programs. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies BB, Blackstock K, Rauschmayer F. ‘Recruitment’, ‘composition’, and ‘mandate’ issues in deliberative processes: should we focus on arguments rather than individuals? Environ Plann C Gov Policy. 2005;23(4):599–615. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dryzek JS, Niemeyer S. Discursive representation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2008;102(4):481–493. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley A, Belcourt-Dittloff A, Belcourt C, Belcourt G. Research ethics and indigenous communities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2146–2152. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minkler M, Hancock T. Community-driven asset identification and issue selection. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ndulue U, Peréa FC, Kayou B, Martinez LS. Team-building activities as strategies for improving community-university partnerships: lessons learned from Nuestro Futuro Saludable. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(2):213–218. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, McDonald K, Dern S, Ashkenazy E, Boisclair C, et al. Collaboration strategies in nontraditional community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons from an academic–community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(2):143–150. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sánchez V, Carrillo C, Wallerstein N. From the ground up: building a participatory evaluation model. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(1):45–52. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burhansstipanov L, Christopher S, Schumacher A. Lessons learned from community-based participatory research in Indian Country. Cancer Control. 2005;12(suppl 2):70–76. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]