ABSTRACT

Propanol stimulates erythromycin biosynthesis by increasing the supply of propionyl coenzyme A (propionyl-CoA), a starter unit of erythromycin production in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Propionyl-CoA is assimilated via propionyl-CoA carboxylase to methylmalonyl-CoA, an extender unit of erythromycin. We found that the addition of n-propanol or propionate caused a 4- to 16-fold increase in the transcriptional levels of the SACE_3398–3400 locus encoding propionyl-CoA carboxylase, a key enzyme in propionate metabolism. The regulator PccD was proved to be directly involved in the transcription regulation of the SACE_3398–3400 locus by EMSA and DNase I footprint analysis. The transcriptional levels of SACE_3398–3400 were upregulated 15- to 37-fold in the pccD gene deletion strain (ΔpccD) and downregulated 3-fold in the pccD overexpression strain (WT/pIB-pccD), indicating that PccD was a negative transcriptional regulator of SACE_3398–3400. The ΔpccD strain has a higher growth rate than that of the wild-type strain (WT) on Evans medium with propionate as the sole carbon source, whereas the growth of the WT/pIB-pccD strain was repressed. As a possible metabolite of propionate metabolism, methylmalonic acid was identified as an effector molecule of PccD and repressed its regulatory activity. A higher level of erythromycin in the ΔpccD strain was observed compared with that in the wild-type strain. Our study reveals a regulatory mechanism in propionate metabolism and suggests new possibilities for designing metabolic engineering to increase erythromycin yield.

IMPORTANCE Our work has identified the novel regulator PccD that controls the expression of the gene for propionyl-CoA carboxylase, a key enzyme in propionyl-CoA assimilation in S. erythraea. PccD represses the generation of methylmalonyl-CoA through carboxylation of propionyl-CoA and reveals an effect on biosynthesis of erythromycin. This finding provides novel insight into propionyl-CoA assimilation, and extends our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis of erythromycin.

KEYWORDS: propionate metabolism, propionyl-CoA assimilation, erythromycin biosynthesis, transcriptional regulation

INTRODUCTION

Saccharopolyspora erythraea, a Gram-positive filamentous soil bacterium, is used for production of the antibiotic erythromycin. Erythromycin and its derivatives play a vital role in medicine, with annual sales reaching several billion dollars annually (1). Historically, multiple rounds of random mutagenesis and selection have been used to obtain overproducing mutants for industrial production. Nowadays, genetic engineering of the pathways involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites also holds promises to enhance production (2–4).

Production of one unit of erythromycin requires one propionyl coenzyme A (propionyl-CoA) to provide a starter unit and six (2S)-methylmalonyl–CoAs to provide extender units to form 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6-dEB) (5). The experiments of Reeves et al. indicated that methylmalonyl-CoA was a limiting factor for erythromycin biosynthesis (6). Engineering of the methylmalonyl-CoA metabolic flux of S. erythraea through knockout of the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase operon resulted in a 50% increase in erythromycin production in an oil-based fermentation medium (7). Integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics comparisons between the wild-type strain and the industrial highly producing strain of S. erythraea revealed that the industrial strain has a high flux of metabolites toward erythromycin biosynthesis and degradation pathway of branched-chain amino acids (8). Because branched-chain amino acids are a source of methylmalonyl-CoA, the significantly higher expression levels of ilvB (acetolactate synthase large subunit gene, SACE_4565), acd (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene, SACE_4125 and SACE_5025), and mmsA (methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase gene, SACE_4672) in the highly producing strain may lead to an increased supply of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA, key precursors for erythromycin synthesis. This is also supported by an increased erythromycin yield when different genes of the branched-chain amino acid metabolism were overexpressed (9). The quantitative analysis of metabolic carbon flux indicated that a high consumption rate of propanol increased propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA concentrations. The addition of n-propanol at a concentration of 1% (vol/vol) increased erythromycin production by 20% (10). Analysis of n-[18O]propanol metabolic carbon flux suggested that the oxygen atoms of 6-dEB are largely derived from n-propanol (11). Propanol is converted into propionate, which is subsequently metabolized to propionyl-phosphate or propionyl-CoA by propionate kinase or acetyl/propionyl-CoA synthetase. However, propionyl-CoA is an inhibitor of CoA-dependent enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, succinyl-CoA synthetase, and ATP citrate lyase (12–16). Therefore, the assimilation of propionyl-CoA needs to be precisely regulated to prevent its accumulation within the cell.

In most microorganisms, so far, two pathways were found for propionyl-CoA assimilation: the methylcitrate cycle (MCC) that converts propionyl-CoA to pyruvate and the propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PCC) pathway, which is responsible for the metabolism of propionyl-CoA to methylmalonyl-CoA. No gene encoding methylcitrate synthase has been found in the genome of S. erythraea. There are at least six genetic loci encoding putative biotin-dependent acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylases, including SACE_0026–0028, SACE_3241–3242, SACE_3398–3400, SACE_7038–7039, SACE_4237, and SACE_3856/6509–6510 (17). Here, we show that only the genetic locus SACE_3398–3400 (herein named pccB, pccC, and pccA) plays an important role in propionyl-CoA assimilation when n-propanol is added for high production of erythromycin. The TetR family transcriptional regulator SACE_3396 (herein named PccD) can bind directly to the promoter regions of pccBC and pccA and negatively regulate their transcription.

RESULTS

The pccBC and pccA operons are induced by propanol and propionate in S. erythraea.

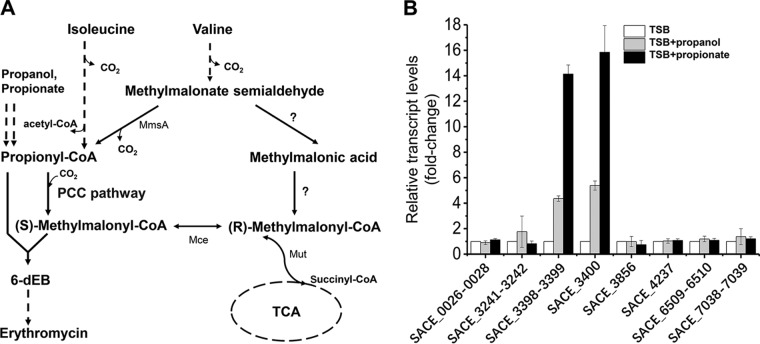

It was reported that propionyl-CoA carboxylases were upregulated when propanol or propionate was added to microorganisms (18, 19). Propanol is converted into propionate, which is subsequently metabolized to propionyl-phosphate or propionyl-CoA by propionate kinase or acetyl/propionyl-CoA synthetase (Fig. 1A). The quantitative analysis of metabolic carbon flux indicated that a high consumption rate of propanol increased intracellular concentration of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA (11) to enhance the biosynthesis of erythromycin. In the genome of S. erythraea, loci for at least six possible acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylases are annotated, namely, SACE_0026–0028, SACE_3241–3242, SACE_3398–3400, SACE_7038–7039, SACE_4237, and SACE_6509 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The cotranscription of genes in each locus was investigated (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). We found that gene pccB (SACE_3398) was cotranscribed with pccC (SACE_3399), forming the pccBC operon, and was not cotranscribed with pccA (SACE_3400). So far, it is still unclear which of the possible propionyl-CoA carboxylases make a contribution to erythromycin biosynthesis. To investigate which genetic loci were responsive to the addition of n-propanol or propionate, transcript levels of all loci encoding acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylases were examined using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 1B). The results showed that transcriptional levels of the pccBC operon and pccA gene increased 4- or 14-fold and 5- or 16-fold, respectively, by addition of propanol or propionate. No changes were observed in transcriptional levels of the other loci coding for acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylases (Fig. 1B). pccB encodes a β-subunit (PccB) that has a carboxyl transferase (CT) activity, and pccA codes for a larger α-subunit (PccA) comprising the biotin carboxylase (BC) and biotin carboxy carrier protein (BCCP). pccC encodes the small ε-subunit (17). These results indicate that pccBC and pccA operons perform a major function in propionate metabolism and propionyl-CoA assimilation.

FIG 1.

pccBC (SACE_3398–3399) and pccA (SACE_3400) operons are induced by propanol and propionate in S. erythraea. (A) In S. erythraea, branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) are a source of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA, key precursors in erythromycin biosynthesis. Valine and isoleucine were metabolized to propionyl-CoA through the degradation pathways. Propanol and propionate are two important external sources of propionyl-CoA, especially in the production of erythromycin. The metabolism of propionyl-CoA to (2S)-methylmalonyl–CoA is via the PCC pathway in S. erythraea, which plays an important role in propionyl-CoA assimilation when n-propanol or valine is added for high production of erythromycin. Enzymes that transform methylmalonate-semialdehyde to (R)-methylmalonyl–CoA (indicated by question marks) have not yet been investigated in S. erythraea. (B) Total RNA of S. erythraea NRRL2338 was extracted after 36 h of growth (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) in TSB medium, TSB supplied with 1% (vol/vol) n-propanol, and TSB supplied with 20 mM propionate. Relative transcript levels were normalized to the 16S rRNA. The transcription value of each gene in S. erythraea in TSB medium was arbitrarily normalized to 1. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three biological replicates. MmsA, methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (acylating); Mut, methylmalonyl-CoA mutase; Mce, methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase.

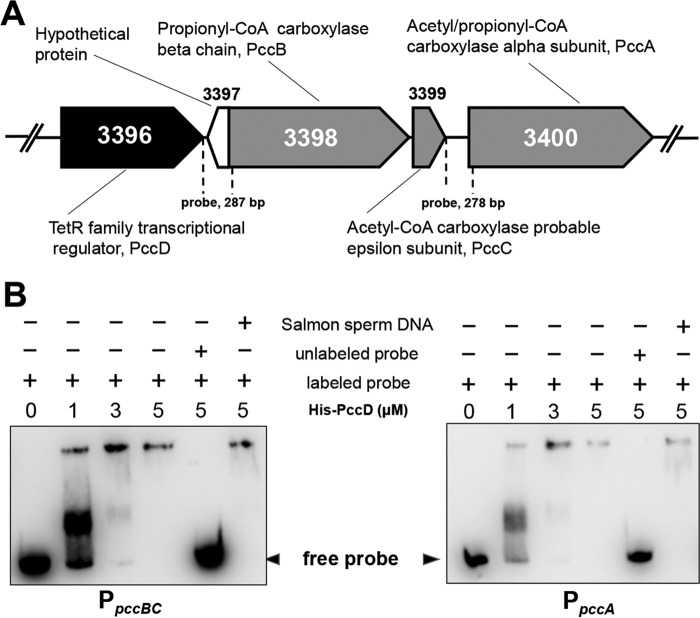

PccD (SACE_3396) binds to the promoter regions of pccBC and pccA operons.

To identify the possible transcriptional regulator controlling pccBC and pccA in S. erythraea, we analyzed their genomic organization. It was found that the SACE_3396 gene encoding a TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator (named PccD) was located upstream of pccBC (Fig. 2A). To examine the binding activity of PccD to pccBC and pccA operons, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed. As shown in Fig. 2B, obvious band shifts were observed, as the entire promoter regions of pccBC and pccA were incubated with purified recombinant His-tagged PccD (fractions G, H and I) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The results indicate that PccD was able to directly interact with the promoter regions of these two operons.

FIG 2.

PccD (SACE_3396) binds to the promoter regions of pccBC and pccA. (A) Genetic organization of the pccD gene in the S. erythraea genome. pccB (SACE_3398), pccC (SACE_3399), and pccA (SACE_3400) encode a propionyl-CoA carboxylase β-chain, acetyl-CoA carboxylase probable ε-subunit, and acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase α-subunit, respectively. The numbers between dashed lines show the lengths of the promoter regions of pccBC and pccA, respectively, used in the gel shift experiment shown in panel B. (B) EMSA of His-PccD protein with promoter regions (separated by dashed lines shown in panel A) of pccBC or pccA. The biotin-labeled DNA probe (about 15 ng, reaction system 10 μl) was incubated with a protein concentration gradient (0, 1, 3, and 5 μM). An unlabeled specific probe (200-fold) or nonspecific competitor DNA (200-fold, sonicated salmon sperm DNA) was used as control. The free probes that did not bind with protein are shown by arrowheads.

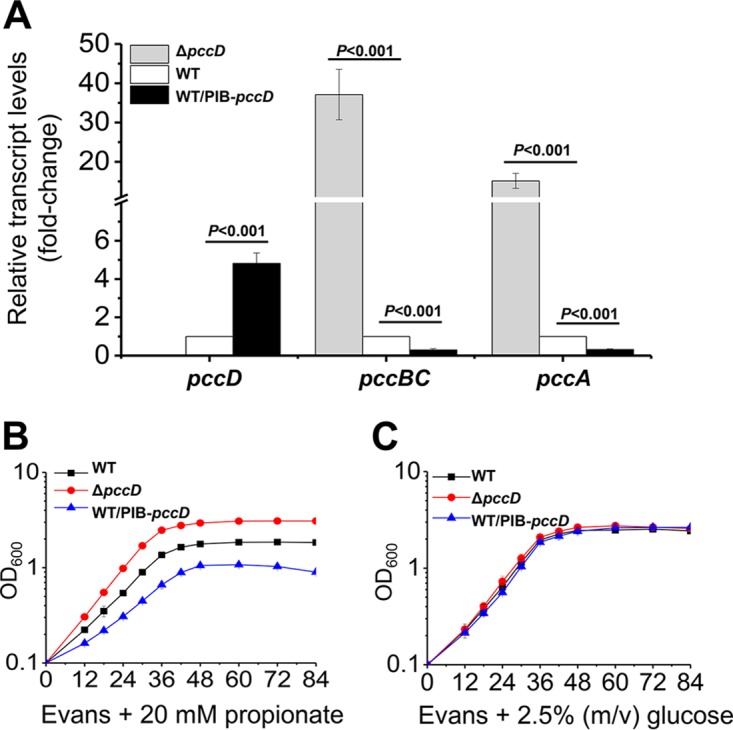

PccD is a transcriptional repressor of pccBC and pccA operons.

To further investigate the regulatory effect of PccD on pccBC and pccA operons, we constructed a pccD-deleted mutant (ΔpccD) and a pccD-overexpressed strain (WT/PIB-pccD) and performed transcriptional analysis by qRT-PCR of wild-type (WT), ΔpccD and WT/PIB-pccD strains. These strains were cultivated in tryptone soya broth (TSB) medium, and RNA was extracted at the late exponential growth/early stationary phase. Results show that deletion of pccD resulted in a 15-fold (for pccA) and 37-fold (for pccBC) upregulation of the pccA and pccBC operons, and that overexpression (approximately 5-fold) of pccD inhibited the expression of two operons by 3-fold compared to that in the WT strain (Fig. 3A). Next, we examined the growth of WT, ΔpccD, and WT/PIB-pccD strains cultivated in Evans media with 20 mM sodium propionate as the sole carbon source. As shown in Fig. 3B, differences in growth behavior were observed among these strains. On one hand, the deletion of pccD significantly promoted propionate metabolism and propionyl-CoA assimilation by inducing the transcription of pccBC and pccA operons, and increased the growth rate of S. erythraea on propionate medium (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). On the other hand, the WT/PIB-pccD strain overexpressing pccD revealed a decrease in growth rate on propionate compared to the wild-type strain due to the low levels of pccBCA transcripts (Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, the WT/PIB-pccD strain showed a decrease in growth yield probably due to the accumulation of toxic propionyl-CoA (12–16). Three strains revealed similar growth curves on Evans media supplied with 2.5% glucose (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these observations further demonstrate that PccD is a transcriptional repressor of pccBC and pccA operons, and inhibits propionyl-CoA assimilation.

FIG 3.

PccD is a repressor of pccBC and pccA operons. (A) qPCR analysis of the relative transcription levels of pccD, pccBC, and pccA genes between the WT, ΔpccD, and WT/PIB-pccD strains. Total RNA of these strains was extracted after 36 h of growth in TSB medium (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material). The expression levels of genes in the WT strain were arbitrarily set to 1.0. Error bars indicate standard deviation from three independent experiments. (B and C) Growth curves of S. erythraea strains WT, ΔpccD, and WT/PIB-pccD grown on Evans medium supplemented with 20 mM sodium propionate (B) or 2.5% glucose (C) as the sole carbon source. Error bars indicate standard deviation from three biological replicates.

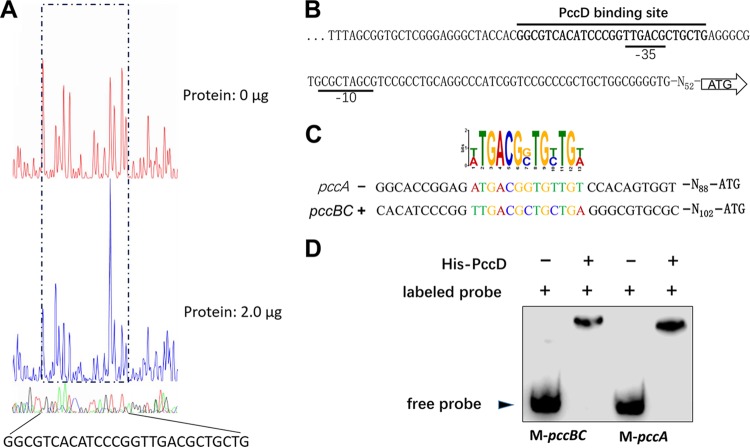

Identification of the PccD-binding sites in upstream regions of pccBC and pccA.

To define the binding sites of PccD, the upstream region (300 bp) of pccBC bound by recombinant His-tagged PccD was investigated by DNase I footprint mapping. As shown in Fig. 4A, a protected region of 27 nucleotides was detected at the position −140 to −114 relative to the translational start site in the pccBC promoter. The −35 promoter sequence (predicted by the Softberry web tool) was located in the protected region (Fig. 4B). A putative PccD-binding motif (t/aTGACGg/cTGt/cTGt/a) was obtained from the protected sequence and the promoter sequence of pccA using MEME (http://meme-suite.org/) (Fig. 4C). To further confirm the putative PccD-binding motif, two short biotin-labeled double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) fragments, named M-pccBC and M-pccA (containing PccD-binding sequences in the upstream regions of pccBC and pccA operons, respectively) were synthesized (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and incubated with purified recombinant His-tagged PccD. The EMSA results showed that the two synthetic fragments containing the PccD-binding motif were sufficient to interact with the His-tagged PccD (Fig. 4D), thus confirming the PccD-binding motif predicted by DNase I footprint mapping and MEME method. No PccD-binding motif was observed in the promoter region of pccD gene. Indeed, EMSA experimental results revealed that PccD did not bind to its own gene promoter (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Identification of a PccD-binding site in pccBC and pccA operons. (A) Electropherograms of a DNase I digest of pccBC promoter probe incubated without (top) or with (bottom) 2.0 μg of His-PccD. The nucleotide sequence protected by His-PccD is indicated below. (B) Protected sequence stretches in the upstream regions of pccBC. Black lines indicate the regions of DNase I protection. The −35 and −10 sites were predicted by the Softberry web tool. (C) Analysis of the PccD-binding motif of pccA using MEME. The standard code of the WebLogo server is shown at the top. (D) Verification of PccD-binding motif by EMSA. Synthetic probes M-pccBC and M-pccA containing PccD-binding site in promoters of pccBC and pccA operons, respectively. The DNA probe was incubated with a protein concentration of 5 μM.

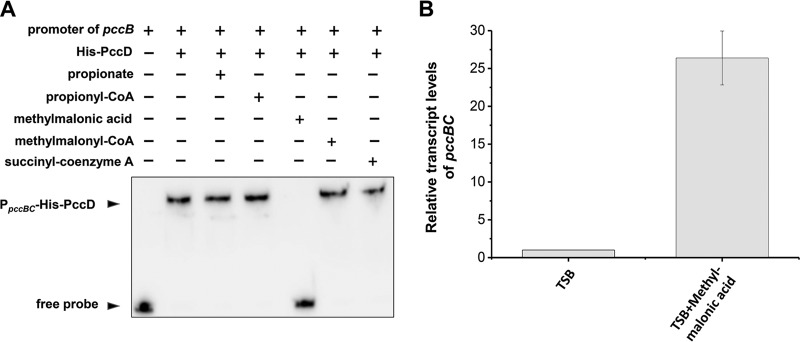

The metabolite methylmalonic acid is an effector of PccD.

TetR/AcrR family transcriptional repressors are homodimeric DNA-binding proteins. Their DNA-binding activity is allosterically inactivated by the binding of small-molecule ligands (effectors). PccD protein from S. erythraea contains two TetR domains and may act as a monomer for DNA-binding. To identify the effector of PccD, we investigated several intermediate metabolites of the propionate metabolism as effector molecules, including propionyl-CoA, methylmalonic acid, methylmalonyl-CoA, and succinyl-CoA, as well as propionate itself. The effect of these compounds on PccD binding to the pccBC promoters was examined using the EMSA. We found that propionate, propionyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, and succinyl-CoA had no effect on the DNA-binding activity of PccD, whereas methylmalonic acid specifically inhibited PccD binding to the pccBC promoter (Fig. 5A). In order to further verify the important effect of methylmalonic acid on pccBC operon transcription in vivo in S. erythraea, 10 mM methylmalonic acid was added to TSB medium and the transcriptional level of pccBC operon was investigated. The results showed that the pccBC operon transcriptional level was increased about more than 26-fold by addition of methylmalonic acid (Fig. 5B). This indicated that methylmalonic acid may exert an important effect on the transcription of the pccBC operon, although there is no direct experimental evidence that methylmalonic acid is an effector of PccD regulator in vivo in S. erythraea.

FIG 5.

The metabolite methylmalonic acid is an inhibitor of PccD. (A) EMSA of His-PccD protein binding to the upstream promoter regions of pccBC. The biotin-labeled DNA probe (about 15 ng, reaction system 10 μl) was incubated with 5 μM His-PccD. Propionate, propionyl-CoA, methylmalonic acid, methylmalonyl-CoA, or succinyl-CoA was added as a cofactor to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. (B) Total RNA of S. erythraea NRRL2338 was extracted after 36 h of growth in TSB medium or TSB supplied with 10 mM methylmalonic acid. Relative transcript levels were normalized to the 16S rRNA. The transcription value of pccBC in S. erythraea WT cultivated in TSB medium was arbitrarily normalized to 1. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three biological replicates.

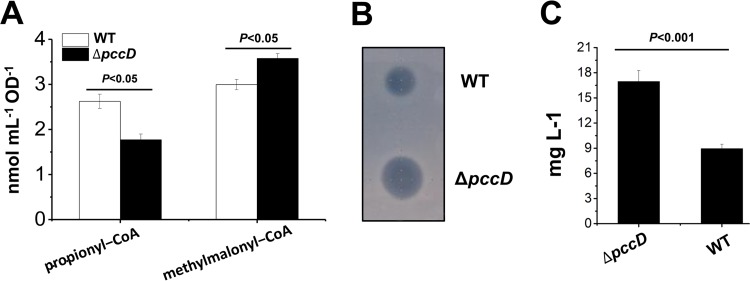

ΔpccD probably promotes erythromycin production by activating propionyl-CoA assimilation.

From the results described above, we speculated that enhancement of the propionyl-CoA carboxylation might result in an increase of intracellular methylmalonyl-CoA and promote erythromycin production. To verify this speculation, we determined the intracellular concentration of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA in WT and ΔpccD strains grown on TSB medium with 1% (vol/vol) n-propanol. As shown in Fig. 6A, the result demonstrated that deletion of pccD promoted propionyl-CoA carboxylation, resulting in a decrease in propionyl-CoA concentration and an increase in methylmalonyl-CoA concentration. It is known that the biosynthesis of a unit erythromycin needs one propionyl-CoA and six (2S)-methylmalonyl–CoAs. A high ratio of methylmalonyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA in the ΔpccD strain will facilitate the biosynthesis of erythromycin. Indeed, the ΔpccD strain revealed a higher erythromycin yield than the WT strain (Fig. 6B and C).

FIG 6.

Apparent increase of erythromycin production in the pccD deletion strain compared to wild type. (A) Intracellular propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA concentration of S. erythraea WT and ΔpccD strains grown in TSB medium with 1% (vol/vol) n-propanol. Cells were harvested at 36 h (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material). (B) Inhibition tests of S. erythraea WT and ΔpccD fermentation broths, collected after culturing for 84 h, against Bacillus subtilis. (C) Erythromycin concentration of S. erythraea WT and ΔpccD strains grown in TSB medium with 1% (vol/vol) n-propanol. Supernatants were collected after culture for 84 h. A turbidimetric method for microbiological assay of antibiotics was used to quantify the erythromycin levels as described in Materials and Methods. Three independent experiments were performed to calculate standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Common and distinctive features of propionyl-CoA assimilation in actinobacteria.

Propionyl-CoA is generated from the β-oxidation of odd-chain fatty acids and branched-chain fatty acids, as well as branched-chain amino acids and cholesterol. Propionyl-CoA is toxic if accumulated inside the cell, and thus propionyl-CoA metabolism needs to be tightly regulated to prevent its accumulation and alleviate toxicity (12–16). In most microorganisms, propionyl-CoA levels are controlled via at least two known metabolic pathways: MCC and the PCC/methylmalonyl-CoA pathway. Propionyl-CoA assimilation and metabolism have been investigated only in a few actinobacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Corynebacterium glutamicum (20–23). Previous studies showed that M. tuberculosis contains both pathways of propionyl-CoA assimilation (24, 25). It was found that S. erythraea has no MCC for propionyl-CoA assimilation. Genome sequence analysis suggests that the PCC pathway plays a role in propionyl-CoA assimilation in S. erythraea. Six genetic loci may encode biotin-dependent carboxylases that catalyze the carboxylation of propionyl-CoA to methylmalonyl-CoA for biosynthesis of erythromycin.

The transcriptional control of gene expression involved in propionyl-CoA assimilation has been investigated in C. glutamicum and M. tuberculosis. In M. tuberculosis, the transcriptional regulator LrpG (also known as PrpR and Rv1129c) controls the expression of genes encoding enzymes of the MCC pathway (24, 26, 27). In C. glutamicum, the PrpR regulator activates the prpDBC2 operon encoding the enzymes 2-methylcitrate dehydratase (PrpD2), 2-methylisocitrate lyase (PrpB2), and 2-methylcitrate synthase (PrpC2); 2-methylcitrate probably acts as coactivator of PrpR (23, 28). The transcriptional regulation of the genes encoding enzymes of the PCC pathway in bacteria remains unknown. Recently, Carter and Alber found that RSP_2186 (designated PccR) controls the transcription of the propionyl-CoA carboxylase gene in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (19). They defined a novel family of short-chain fatty acyl-CoA regulators (ScfRs) that modulate pathways for short-chain acyl-CoA assimilation in microorganisms, including PccR (PCC pathway for propionyl-CoA assimilation), MccR (MCC for propionyl-CoA assimilation), RamB (glyoxylate bypass for acetyl-CoA assimilation), and IbcR (for isobutyryl-CoA assimilation) (19). ScfRs typically belong to the xenobiotic response element (XRE) family and have a helix-turn-helix N-terminal domain for DNA binding and a C-terminal domain of unknown function (DUF2083) as common features. In this study, we found that the TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator PccD negatively controlled propionyl-CoA assimilation. S. erythraea PccD is a novel ScfR, as it does not belong to the XRE family regulator described by Carter and Alber (19).

BldD, a key developmental regulator in actinobacteria, was identified as directly activating the transcription of all genes involved in the biosynthesis of erythromycin (29). More recently, it was found that two TetR family regulators (SACE_7301 and SACE_3986) were associated with biosynthesis of erythromycin in S. erythraea A226. SACE_7301 activated the transcription of the erythromycin biosynthetic gene eryAI and the resistance gene ermE by interacting with their promoter regions (30). SACE_3986 negatively controlled erythromycin biosynthesis by reducing the transcription of its adjacent gene SACE_3985, which codes for a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (31). Herein, PccD, a TetR family regulator, was found to negatively regulate erythromycin biosynthesis by repressing feeder pathways.

The important role of propionyl-CoA carboxylation for high production of erythromycin with n-propanol supplementation.

In S. erythraea, branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) are a source of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA, key precursors in erythromycin biosynthesis. As shown in Fig. 1A, two degradation pathways of valine may exist for the generation of methylmalonyl-CoA from valine: the MPMS (Val→methylmalonate-semialdehyde→propionyl-CoA→methylmalonyl-CoA→succinyl-CoA) pathway and the predicted MMMS (Val→methylmalonate-semialdehyde→methylmalonate→methylmalonyl-CoA→succinyl-CoA) pathway (32, 33). Methylmalonyl-CoA is a limiting factor for erythromycin biosynthesis. In actinobacteria, at least four pathways have been found to generate methylmalonyl-CoA: (i) the PCC pathway for carboxylation of propionyl-CoA by propionyl-CoA carboxylase, (ii) the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MCM) pathway that catalyzes the reversible isomerization of succinyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, (iii) the CCR pathway through crotonyl-CoA reductase or isobutyryl-CoA mutase, and (iv) the meaA pathway from acetoacetyl-CoA (8, 17). No CCR or meaA pathway is found in S. erythraea, whereas the PCC and MCM pathways play important roles in the precursor supply under different conditions (6–8, 17). Reeves et al. have proposed a metabolic model in which, in carbohydrate-based fermentations, MCM acts as a drain on the methylmalonyl-CoA metabolite pool; in oil-based fermentations, MCM acts in the reverse direction to fill the methylmalonyl-CoA pool (7). Engineering of the methylmalonyl-CoA metabolic flux of S. erythraea through duplication of the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase operon resulted in a 50% increase in erythromycin production in an oil-based fermentation medium (7). Under industrial medium conditions, the increase in methylmalonyl-CoA pool is mainly attributed to the PCC pathway from propionyl-CoA. Some genes involved in the branched-chain amino acid degradation pathway, such as ilvB (SACE_4565), acd (SACE_4125 and SACE_5025), and mmsA (SACE_4672), are significantly upregulated in industrial highly producing strains. These results indicate that propionyl-CoA can be derived from valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation (9). The addition of n-propanol to the medium significantly increases the propionyl-CoA pool as a result of propionate metabolism by acetyl/propionyl-CoA synthetases. Therefore, PccD-regulated PCC-pathway for propionyl-CoA carboxylation plays an important role in high erythromycin production.

In conclusion, short-chain acyl-CoAs are intermediates and precursors for the biosynthesis of many antibiotics. The regulation of their supplies is crucial for increasing antibiotic yield. Our work has identified the novel regulator PccD that controls the gene expression of propionyl-CoA carboxylase, which is responsible for propionyl-CoA assimilation in S. erythraea. PccD represses the generation of methylmalonyl-CoA through carboxylation of propionyl-CoA and reveals an effect on biosynthesis of erythromycin. A higher level of erythromycin in the ΔpccD strain was observed compared with that in the wild-type strain. Our study reveals a regulatory mechanism in propionate metabolism and suggests new possibilities for designing metabolic engineering to increase erythromycin yield.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. erythraea NRRL2338 was grown on R2YE agar plates for 5 to 6 days at 30°C for sporulation. An agar piece of about 1 cm2 was inoculated into a 150-ml flask containing 30 ml of tryptone soya broth (TSB) medium and grown at 30°C and 200 rpm for 48 h for seed stock preparation. Prior to inoculation, the seed was centrifuged at 2,880 × g for 10 min at 4°C to form a pellet and then resuspended and washed three times with the next corresponding medium. Next, about 0.5 to 1 ml of the seed culture was added to a 500-ml flask containing 50 ml TSB (initial optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.05) or minimal Evans medium (36) (initial OD600 = 0.1) supplemented with various carbon sources grown at 30°C and 200 rpm for genomic DNA extraction, phenotype, or transcription studies.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. erythraea NRRL2338 | Used as parental strain, wild type | DSM 40517 |

| ΔpccD strain | S. erythraea pccD null mutant, thiostrepton resistance | This work |

| WT/PIB-pccD | pccD overexpression strain, WT carrying pIB-pccD | This work |

| E. coli Rosetta (DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm λ(DE3)pRARE2(Camr) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET19b | Expression vector, Ampr | Novagen |

| pET-pccD | pET19b derivative carrying pccD | This work |

| pMD-18T | TA-cloning vector | TaKaRa |

| pUC19-tsr | pUC18 derivative containing a 1.36-kb fragment of a thiostrepton resistance cassette in the BamHI/SmaI sites | 34 |

| pUC-pccD | pUC19-tsr, with the 1.5-kb DNA fragments upstream and downstream of pccD gene inserted upstream and downstream of tsr correspondingly | This work |

| pIB139 | E. coli-S. erythraea integrative shuttle vector containing a strong constitutive ermE* promoter, apramycin resistance | 35 |

| pIB-pccD | pIB139 carrying an extra pccD for the gene overexpression | This work |

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR.

S. erythraea wild-type (WT), pccD gene deletion (ΔpccD), and pccD overexpression (WT/PIB-pccD) strains were grown to late-exponential growth/early stationary phase at 30°C in TSB liquid media or TSB supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) propanol, 20 mM propionate, or 10 mM methylmalonic acid. The cells were harvested at 36 h by centrifugation at 4°C, 1,500 × g for 10 min. Total RNA was prepared using the RNAprep pure cell/bacteria kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). RNA integrity was analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA concentration was quantitated by SynergyMx multimode microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). DNase digestion was performed to remove genomic DNA before reverse transcription for 5 min at 42°C. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq GC kit (TaKaRa, Japan), and about 50 ng cDNA was added to a final PCR volume of 20 μl. PCR was performed using the primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) with a final concentration of 0.25 μM. PCR assays were carried out using a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad, CA) with the thermocycling conditions as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension cycle at 72°C for 10 min. 16S_rRNA is used as the reference gene. qRT-PCR validation information on amplification efficiency, calibration curves with slope and R2, and specificity (melt) are shown in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. Data analyses of qRT-PCR are shown in Data Sets S2 to S4 in the supplemental material. STDEV indicates the standard deviation derived from three independent experiments.

Protein overexpression and purification.

To produce the PccD protein, the pccD gene was amplified from S. erythraea NRRL2338 by PCR using pccD-F/-R primers (Table S1) and cloned into pET-19b, generating the recombinant plasmid pET-pccD (Table 1). The correct gene sequences were confirmed by sequencing analysis and the recombinant plasmids were introduced into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) competent cells. The recombinant cells selected by ampicillin were grown in 5 ml LB medium with 100 mg liter−1 ampicillin in an orbital shaker (200 rpm, 37°C) for 12 h. Next, 2.5 ml of the seed culture was added to a 250-ml flask containing 50 ml terrific broth (TB) medium (24 g liter−1 yeast extract, 12 g · liter−1 tryptone, 0.4% glycerol, 17 mM KH2PO4, and 72 mM K2HPO4) followed by incubation at 20°C for 20–24 h. His6-tagged PccD protein (His-PccD) was purified from Rosetta (DE3)-harboring pET-pccD as previously described (37). Purity of the purified protein was checked by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S4). The fractions G, H, and I were pooled and used in the assay. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

The putative promoter regions of the target genes were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were labeled with biotin using a universal biotinylated primer (5′biotin-AGCCAGTGGCGATAAG-3′). The biotin-labeled PCR products were purified using the PCR purification kit (Shanghai Generay Biotech, China) as electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) probes. EMSAs were carried out using a chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), as previously described (37). Biotin-labeled DNA probes were incubated with a gradient concentration of proteins at 25°C for 20 min. For control groups, an unlabeled specific probe (200-fold) or nonspecific competitor DNA (200-fold, sonicated salmon sperm DNA) was used. Samples were separated by 6% nondenaturing PAGE gels in ice-cold 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA at 160 V, and bands were detected by BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

To verify the conserved PccD-binding motif, two short biotin-labeled dsDNA probe named M-pccBC and M-pccA, containing PccD-binding site in the promoters of pccBC and pccA operons, respectively, were synthesized (Table S1) and incubated with purified recombinant His-tagged PccD. In EMSA, an excess of poly[d(I-C)] was added during incubation to avoid nonspecific binding of the protein to the DNA.

Construction of the pccD in-frame deletion mutant and overexpression strain.

For an insertional deletion of the pccD gene, a previously described homologous recombination strategy was used (34). 1.5-kb DNA fragments upstream and downstream of the pccD gene locus were amplified from S. erythraea NRRL2338 genomic DNA by PCR using the primer pair pUC3396upF/R, pUC3396dwF/R (Table S1). The PCR products were digested with HindIII/XbaI and KpnI/EcoRI and subsequently inserted into the corresponding sites of pUC19-tsr, creating pUC-pccD knockout plasmids (Table 1). The thiostrepton-resistance cassette amplified from pUC-pccD knockout plasmids by PCR using the primer pair pUC3396upF/pUC3396dwR was transferred into S. erythraea by polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation. The mutants were selected by thiostrepton on R3M agar plates. The selected mutants were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Primers are listed in Table S1.

For overexpression of the mutants, the pccD gene was PCR-amplified with the primer pair 3396over-F/R (Table S1). The PCR products were then cloned into NdeI/NotI sites of pIB139, creating the pIB-pccD plasmid (Table 1). The overexpression plasmids were introduced into the pccD mutant strain (SeryΔpccD) by PEG-mediated transformation. The desired overexpression strains were screened by apramycin resistance and confirmed by PCR.

Erythromycin assay.

A turbidimetric method for microbiological assay of antibiotics was used to quantify the erythromycin levels as previously described (38), with modifications. Briefly, the supernatant (cultivated in TSB with 1% [vol/vol] n-propanol) was collected after culture for 84 h of the S. erythraea wild-type (WT), pccD deficient strain (ΔpccD) and diluted by 40 times before use as test samples. Staphylococcus aureus was cultivated on medium (peptone, 6 g; pancreatic digest of casein, 4 g; beef extract, 1.5 g; yeast extract, 3 g; glucose monohydrate, 1 g; and agar, 15 g; per 1,000 ml water) for 16 to 18 h at 37°C for use as the sensitive microorganism. 15 μl erythromycin standard (0.1 μg to 0.8 μg) or test sample was added to a 96-well plate. 135 μl medium (peptone, 6 g; beef extract, 1.5 g; yeast extract, 3 g; sodium chloride, 3.5 g; glucose monohydrate, 1 g; dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 3.68 g; potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 1.32 g; per 1,000 ml water) containing a suspension of Staphylococcus aureus (to a final OD of 0.05) was added to the wells. Formaldehyde was used as blank to set the optical apparatus. The 96-well plate was placed in a microplate plate incubator at 37°C for 3 to 4 h (OD600 was controlled in the range 0.1 to 0.5). The growth of the microorganisms was stopped by adding 7.5 μl of formaldehyde to each well. OD was measured by SynergyMx multimode microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Three independent experiments were performed to calculate standard deviation. The bioassay-based erythromycin analysis was also carried out as previously described (30).

Determination of intracellular propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA concentrations.

For determination of propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA concentrations, CoA compound extraction and chromatography were performed as previously described (39). Cells grown for 36 h in TSB medium with 1% (vol/vol) n-propanol were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 8.0), and lysed in lysis buffer (10% trichloroacetic acid and 2 mM dithiothreitol). The cell lysates were frozen and thawed out repeatedly with liquid nitrogen and ice water 2 or 3 times, centrifuged at 4°C, 15,000 × g, for 10 min, and transferred to an equilibrated solid-phase extraction column (Sep-Pak, 1 ml, 50 mg tC18; Waters, Milford, MA). After samples were adsorbed, the columns were washed by 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and eluted by 40% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. The eluate was dried by SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and stored at −80°C. For chromatography, the two mobile-phase solvents used were buffer A (75 mM KH2PO4, pH 5.5) and buffer B (800 ml of 75 mM KH2PO4, pH 5.0, mixed with 200 ml of 20% acetonitrile). The chromatographic separations were performed at room temperature at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min on an ODS C18 column and the samples were monitored at 254 nm. The mobile phase composition profile was divided into several linear gradient segments, with sequential segment endpoints of 10 min (when buffer B reached 28% from 10%), 15 min (buffer B reached 30% from 28%), 25 min (buffer B 40% reached from 30%), 26 min (buffer B reached 42% from 40%), 35 min (buffer B reached 54% from 42%), and 36 min (buffer B was reduced from 54% to 10%). After a 14-min constant buffer B level of 10%, data collection was stopped at 50 min. Three independent experiments were performed to calculate standard deviation.

DNase I footprinting assay.

The promoter region of pccB (SACE_3398) was amplified by PCR with primers pMD18T-3398F and -R (Table S1) and the amplicon was cloned into the T-vector pMD-18T (TaKaRa). For preparation of fluorescent 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled probes, the promoter region of pccB was PCR-amplified from the obtained plasmids using primers of M13R-48 (FAM) and M13F-47. The FAM-labeled probes were purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo Fisher). DNase I footprinting assays were performed as previously described (40). For each assay, 500 ng of probes were incubated with different amounts of His-PccD in a total volume of 40 μl. After incubation for 30 min at 25°C, a 10 μl solution containing about 0.015 unit DNase I (Promega) and 100 nmol freshly prepared CaCl2 was added and further incubated for 1 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 140 μl DNase I stop solution (200 mM unbuffered sodium acetate, 30 mM EDTA, and 0.15% SDS). Samples were first extracted with phenol-chloroform and then precipitated with ethanol, and the pellets were dissolved in 30 μl MiniQ water. The preparation of the DNA ladder, electrophoresis, and data analysis were previously described (40), except that the GeneScan-LIZ500 size standard (Applied Biosystems) was used.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21575089, 21335003, and 21276079) and the National High-tech R&D Program (863 Program) (grant no. 2014AA021502).

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00281-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. 2001. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep 18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Zhao Y, Ruan L, Yang S, Ge M, Jiang W, Lu Y. 2015. A stepwise increase in pristinamycin II biosynthesis by Streptomyces pristinaespiralis through combinatorial metabolic engineering. Metab Eng 29:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W, Tian J, Li L, Ge M, Zhu H, Zheng G, Huang H, Ruan L, Jiang W, Lu Y. 2015. Identification of two novel regulatory genes involved in pristinamycin biosynthesis and elucidation of the mechanism for AtrA-p-mediated regulation in Streptomyces pristinaespiralis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:7151–7164. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Feng R, Zheng G, Tian J, Ruan L, Ge M, Jiang W, Lu Y. 2015. Involvement of the TetR-type regulator PaaR in the regulation of pristinamycin I biosynthesis through an effect on precursor supply in Streptomyces pristinaespiralis. J Bacteriol 197:2062–2071. doi: 10.1128/JB.00045-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staunton J, Wilkinson B. 1997. Biosynthesis of erythromycin and rapamycin. Chem Rev 97:2611–2630. doi: 10.1021/cr9600316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves AR, Cernota WH, Brikun IA, Wesley RK, Weber JM. 2004. Engineering precursor flow for increased erythromycin production in Aeromicrobium erythreum. Metab Eng 6:300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves AR, Brikun IA, Cernota WH, Leach BI, Gonzalez MC, Weber JM. 2007. Engineering of the methylmalonyl-CoA metabolite node of Saccharopolyspora erythraea for increased erythromycin production. Metab Eng 9:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li YY, Chang X, Yu WB, Li H, Ye ZQ, Yu H, Liu BH, Zhang Y, Zhang SL, Ye BC, Li YX. 2013. Systems perspectives on erythromycin biosynthesis by comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of S. erythraea E3 and NRRL2338 strains. BMC Genomics 14:523. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karnicar K, Drobnak I, Petek M, Magdevska V, Horvat J, Vidmar R, Baebler S, Rotter A, Jamnik P, Fujs S, Turk B, Fonovic M, Gruden K, Kosec G, Petkovic H. 2016. Integrated omics approaches provide strategies for rapid erythromycin yield increase in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Microb Cell Fact 15:93. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0496-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Enshasy HA, Mohamed NA, Farid MA, El-Diwany AI. 2008. Improvement of erythromycin production by Saccharopolyspora erythraea in molasses based medium through cultivation medium optimization. Bioresour Technol 99:4263–4268. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Huang M, Wang Z, Chu J, Zhuang Y, Zhang S. 2013. Controlling the feed rate of glucose and propanol for the enhancement of erythromycin production and exploration of propanol metabolism fate by quantitative metabolic flux analysis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 36:1445–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00449-013-0883-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock M, Buckel W. 2004. On the mechanism of action of the antifungal agent propionate. Eur J Biochem 271:3227–3241. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregersen N. 1981. The specific inhibition of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from pig kidney by propionyl-CoA and isovaleryl-Co-A. Biochem Med 26:20–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(81)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama K, Kitamura H. 1985. Mechanisms of growth inhibition by propionate and restoration of the growth by sodium bicarbonate or acetate in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Biochem 98:819–824. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwab MA, Sauer SW, Okun JG, Nijtmans LG, Rodenburg RJ, van den Heuvel LP, Drose S, Brandt U, Hoffmann GF, Ter Laak H, Kolker S, Smeitink JA. 2006. Secondary mitochondrial dysfunction in propionic aciduria: a pathogenic role for endogenous mitochondrial toxins. Biochem J 398:107–112. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw L, Engel PC. 1985. The suicide inactivation of ox liver short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase by propionyl-CoA. Formation of an FAD adduct. Biochem J 230:723–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliynyk M, Samborskyy M, Lester JB, Mironenko T, Scott N, Dickens S, Haydock SF, Leadlay PF. 2007. Complete genome sequence of the erythromycin-producing bacterium Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL2338. Nat Biotechnol 25:447–453. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong PK, Burja AM, Radianingtyas H, Fazeli A, Wright PC. 2007. Proteome analysis of Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 propanol metabolism. J Proteome Res 6:1430–1439. doi: 10.1021/pr060575g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter MS, Alber BE. 2015. Transcriptional regulation by the short-chain fatty acyl coenzyme A regulator (ScfR) PccR controls propionyl coenzyme A assimilation by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 197:3048–3056. doi: 10.1128/JB.00402-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Upton AM, McKinney JD. 2007. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in propionate metabolism and detoxification in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 153:3973–3982. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eoh H, Rhee KY. 2014. Methylcitrate cycle defines the bactericidal essentiality of isocitrate lyase for survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4976–4981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400390111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claes WA, Puhler A, Kalinowski J. 2002. Identification of two prpDBC gene clusters in Corynebacterium glutamicum and their involvement in propionate degradation via the 2-methylcitrate cycle. J Bacteriol 184:2728–2739. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.10.2728-2739.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohde KH, Veiga DF, Caldwell S, Balazsi G, Russell DG. 2012. Linking the transcriptional profiles and the physiological states of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during an extended intracellular infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002769. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin JE, Pandey AK, Gilmore SA, Mizrahi V, McKinney JD, Bertozzi CR, Sassetti CM. 2012. Cholesterol catabolism by Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires transcriptional and metabolic adaptations. Chem Biol 19:218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savvi S, Warner DF, Kana BD, McKinney JD, Mizrahi V, Dawes SS. 2008. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J Bacteriol 190:3886–3895. doi: 10.1128/JB.01767-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta P, Shi L, Bibi N, Balazsi G, Gennaro ML. 2011. Regulation of central metabolism genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by parallel feed-forward loops controlled by sigma factor E (sigma(E)). J Bacteriol 193:1154–1160. doi: 10.1128/JB.00459-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masiewicz P, Brzostek A, Wolanski M, Dziadek J, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J. 2012. A novel role of the PrpR as a transcription factor involved in the regulation of methylcitrate pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 7:e43651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plassmeier J, Persicke M, Puhler A, Sterthoff C, Ruckert C, Kalinowski J. 2012. Molecular characterization of PrpR, the transcriptional activator of propionate catabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 159:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chng C, Lum AM, Vroom JA, Kao CM. 2008. A key developmental regulator controls the synthesis of the antibiotic erythromycin in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803622105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H, Chen M, Mao Y, Li W, Liu J, Huang X, Zhou Y, Ye BC, Zhang L, Weaver DT, Zhang B. 2014. Dissecting and engineering of the TetR family regulator SACE_7301 for enhanced erythromycin production in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Microb Cell Fact 13:158. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu P, Pan H, Zhang C, Wu H, Yuan L, Huang X, Zhou Y, Ye BC, Weaver D, Zhang L, Zhang B. 2014. SACE_3986, a TetR family transcriptional regulator, negatively controls erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41:1159–1167. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esser D, Kouril T, Talfournier F, Polkowska J, Schrader T, Brasen C, Siebers B. 2013. Unraveling the function of paralogs of the aldehyde dehydrogenase super family from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles 17:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s00792-012-0507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes AJ, Keatinge-Clay A. 2011. Enzymatic extender unit generation for in vitro polyketide synthase reactions: structural and functional showcasing of Streptomyces coelicolor MatB. Chem Biol 18:165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han S, Song P, Ren T, Huang X, Cao C, Zhang B. 2011. Identification of SACE_7040, a member of TetR family related to the morphological differentiation of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Curr Microbiol 63:121–125. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9943-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson CJ, Hughes-Thomas ZA, Martin CJ, Böhm I, Mironenko T, Deacon M, Wheatcroft M, Wirtz G, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 2002. Increasing the efficiency of heterologous promoters in actinomycetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 4:417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fink D, Weissschuh N, Reuther J, Wohlleben W, Engels A. 2002. Two transcriptional regulators GlnR and GlnRII are involved in regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol 46:331–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao CH, Yao LL, Ye BC. 2014. Three genes encoding citrate synthases in Saccharopolyspora erythraea are regulated by the global nutrient-sensing regulators GlnR, DasR, and CRP. Mol Microbiol 94:1065–1084. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kersey RC, Fink FC. 1954. Microbiological assay of antibiotics, p 53–79. In Glick D. (ed), Methods of biochemical analysis, vol 1 Interscience Publisher, Inc., New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boynton ZL, Bennett GN, Rudolph FB. 1994. Intracellular concentrations of coenzyme A and its derivatives from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 and their roles in enzyme regulation. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Cen XF, Zhao GP, Wang J. 2012. Characterization of a new GlnR binding box in the promoter of amtB in Streptomyces coelicolor inferred a PhoP/GlnR competitive binding mechanism for transcriptional regulation of amtB. J Bacteriol 194:5237–5244. doi: 10.1128/JB.00989-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.