Abstract

Background and Objective

Restrictive use of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in preterm infants reduces the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Our objective was to determine its effect on neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) at 24 months' corrected age (CA).

Methods

This retrospective single-center cohort study included all patients with a gestational age <30 weeks born in 2004/2005 (epoch 1) and 2010/2011 (epoch 2). In epoch 2, we introduced a policy of restriction on IMV and liberalized the use of respiratory stimulants in the delivery room and neonatal intensive care. Data on patient characteristics, respiratory management, short-term outcomes, mortality, BPD, and NDI at 24 months' CA were collected.

Results

Four hundred and four preterm infants were included. Compared to those in epoch 1, infants in epoch 2 were less likely to be intubated and the duration of IMV was shorter. Other noninvasive adjuvant therapies such as caffeine, doxapram, and nasal ventilation were more often used during epoch 2. There was a trend to less BPD in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1 (17 vs. 23%, adjusted OR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.48, 1.16). Mortality did not change over time. The combined outcome death or NDI at 24 months' CA was significantly lower in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1 (24.7 vs. 33.9%, adjusted OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.97).

Conclusions

Restricted use of IMV is feasible in preterm infants and might be associated with a reduced risk of the combined outcome death or NDI at 24 months' CA. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Invasive mechanical ventilation, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, Neurodevelopmental impairment

Background

Approximately 65% of the preterm infants with birth weight <1,500 g are supported by invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) during their admission and/or in the delivery room (DR) [1]. Although IMV improves the patients' respiratory status, it can also result in serious complications with long-lasting consequences. First, IMV is associated with an increased risk of air leak syndrome [2]. Second, it is considered an important risk factor for developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [3]. BPD may lead to a compromised lung function lasting into adolescence and is also considered an independent risk factor for neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) [4]. Finally, protracted IMV itself is also associated with in an increased risk of NDI [5].

In an attempt to reduce these adverse effects of IMV, preterm infants are increasingly managed on noninvasive respiratory support often started in the DR [1]. Studies have shown that restricting the use of IMV is feasible in clinical practice and is associated with a reduction in the incidence of BPD [6,7]. Interestingly, none of these studies reported the impact of restricted use of IMV on NDI [5].

After an implementation period, our neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) officially adapted a respiratory support protocol in January 2010 that restricted the use of IMV, both in the DR and the NICU. The aim of this study is to investigate the feasibility of this protocol and to assess its effect on pulmonary outcomes and, more importantly NDI.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study included all preterm patients with a gestational age (GA) <30 weeks admitted to the NICU of the Academic Medical Center (AMC) between January 2004 and December 2005 (epoch 1) and January 2010 and December 2011 (epoch 2). Infants were excluded if they were initially treated in one of the other Dutch NICUs or if they had a congenital anomaly. At the start of the second epoch, the threshold of viability in the Netherlands was lowered from 25 to 24 weeks. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Respiratory Management

In epoch 1, initial respiratory management in the DR consisted of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) (5-8 cm H2O) using a T-piece resuscitator with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 1.0. Apnea or insufficient breathing was treated by applying peak inflation pressures of 20-30 cm H2O. The FiO2 was titrated based on postductal oxygen saturation (target: 86-94%) measured with pulse oximetry (SpO2). Infants were intubated and ventilated in the DR when needing a FiO2 >0.40 with signs of ongoing distress. If this was not the case, patients were transferred to the NICU on nCPAP and remained on this mode unless one or more of the following failure criteria occurred: FiO2 increased to >0.40 with signs of respiratory distress; more than one apnea per hour requiring vigorous stimulation or bag-and-mask ventilation; hypercarbia resulting in pH <7.2. In case of apnea, infants were started on caffeine. All infants needing IMV in the NICU were started primarily on high-frequency ventilation as previously described [8]. Surfactant was administered via the endotracheal tube if the respiratory index >2.5. The aim was to extubate the patients from high-frequency ventilation to nCPAP within the first 72 h after birth. Noninvasive ventilation was not yet implemented in daily clinical practice. The use of doxapram to treat apnea of prematurity was restricted to infants older than 4 weeks and on full enteral feeds.

In epoch 2, three fundamental changes were adopted in the DR respiratory management. First, FiO2 was titrated strictly based on the preductal oxygen saturation (target: 86-94%). Second, the initial FiO2 administered at the time of birth was reduced to 0.40 and thereafter titrated according to published SpO2 preterm reference ranges [9]. Third, infants were only intubated if they needed to be resuscitated, defined as persistent bradycardia needing chest compression. Oxygen need >0.40 to target SpO2 and/or severe respiratory distress were no longer reasons to start IMV in the DR. After being transferred to the NICU, patients meeting the aforementioned nCPAP failing criteria were intubated, started on open-lung high-frequency ventilation, and – if indicated – treated with exogenous surfactant. However, weaning and extubation was more aggressive compared to epoch 1, aiming to transfer patients back to nCPAP within the first 12 h of life. After the first 72 h of life, the aim was to keep the infants on noninvasive support by using caffeine, noninvasive ventilation, and permissive hypercapnia. In addition, doxapram could be used in all infants failing these noninvasive treatment options.

Data Collection

A predefined set of demographics, patient characteristics, and outcomes was collected (see Appendix). Using the international criteria, patients were diagnosed as having no, mild, moderate, or severe BPD by combining data collected at AMC as well as the regional level II hospital the baby was transferred to [3,10].

Follow-up at 24 months' corrected age (CA) consisted of neurological examination and assessment of the Mental Development Index (MDI) and Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID). In epoch 1, the second and in epoch 2 the third edition of the BSID was used [11]. To allow for epoch comparison, we added 5 points to the MDI of the BSID-II, as was previously done [12]. Since the BSID-III Motor Composite is on average 10 points (range: 6-14) higher than the BSID-II PDI of the BSID-II, we added 10 points to the PDI of the BSID-II [13]. An abnormal cognitive and motor development was defined as a (corrected) MDI and/or PDI of less than −1 SD below the mean. Cerebral palsy was diagnosed according to international standards [14], and all levels were included. NDI was defined as one or more of the following outcomes: MDI or PDI score less than −1 SD, cerebral palsy, hearing loss despite amplification, and visual impairment leading to blindness or only light perception in at least one eye.

Data Analysis

Data were expressed as means with SD or medians with interquartile range, depending on their distribution. Because of the different thresholds of viability between the two epochs, data are presented with and without infants born at a GA <25 weeks. Univariate analyses comparing the two epochs were done using χ2 tests for dichotomous data and independent samples t tests for continuous data. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of respiratory management during the two epochs on mortality, BPD, and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome. To maximize comparability of both epochs, we only included infants born ≥25 weeks' gestation in this analysis. Furthermore, we identified all possible confounders based on a known association with one or more of the main outcomes mortality, BPD, and NDI (GA, small for gestational age defined as weight <10th percentile according to the Dutch reference curves, chorioamnionitis, singleton, and outborn), or differences between both epochs in the univariate analysis with p < 0.2 (Apgar score) [15,16,17]. Next, we performed a multiple logistic regression analysis correcting for these confounders present at birth. In a second analysis, we also added the intermediate NEC occurring during hospitalization for the outcome BPD, and NEC and IVH for the long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes [18,19]. Differences in respiratory variables and outcomes that might have an impact on mortality, BPD, or NDI were not entered as intermediates in the multiple regression analysis because these were considered part of the noninvasive respiratory support policy. To assess selection bias due to lost to follow-up at 24 months' CA, we compared patient characteristics and respiratory outcomes between infants assessed and those lost to follow-up. Complete case analysis was performed. Differences were considered statistically significant when the 2-tailed p value was <0.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

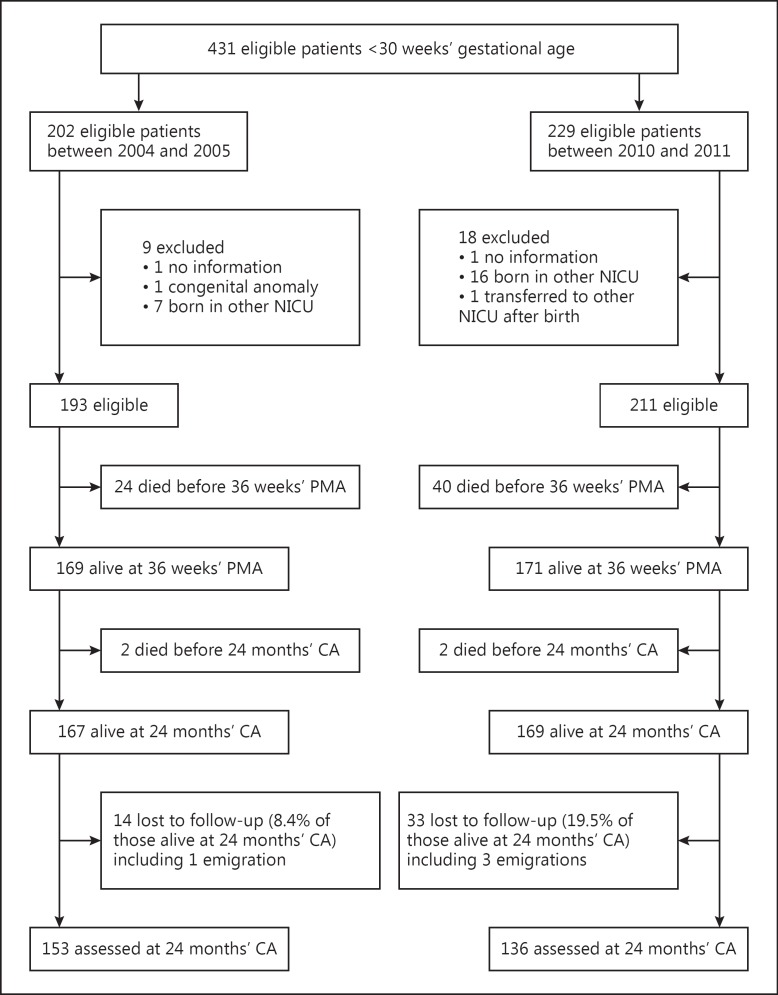

During the two study periods, 431 eligible infants were admitted. Twenty-seven were excluded, mostly because they were born in another NICU and transferred to the AMC at a later age (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 404 patients, 193 were born in epoch 1, and 211 in epoch 2. Infants in epoch 2 had a significantly lower GA, were more often singletons, and had a slightly lower 5-min Apgar score compared to infants born in epoch 1 (Table 1). Surfactant was administered less while caffeine, doxapram, and noninvasive ventilation were used more in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patient inclusion. PMA, postmenstrual age; CA, corrected age; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Total cohort |

Infants ≥25 weeks' gestational age |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004/2005 (n = 193) | 2010/2011 (n = 211) | p | 2004/2005 (n = 192) | 2010/2011 (n = 190) | p | |

| Gestational agea, weeks | 28.1 ± 1.3 | 27.6 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | 28.1 ± 1.3 | 28.0 ± 1.3 | 0.19 |

| Birth weighta, g | 1,086 ± 270 | 1,024 ± 284 | 0.45 | 1,088 ± 269 | 1,063 ± 270 | 0.38 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 33 (17) | 24 (11) | 0.10 | 32 (17) | 20 (11) | 0.10 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 106 (55) | 124 (59) | 0.44 | 105 (55) | 112 (59) | 0.41 |

| Singleton, n (%) | 130 (67) | 159 (75) | 0.08 | 129 (67) | 149 (78) | 0.02 |

| Toxemiab, n (%) | 36 (19) | 42 (20) | 0.75 | 36 (19) | 42 (22) | 0.45 |

| PPROM, n (%) | 37 (19) | 44 (21) | 0.67 | 37 (19) | 39 (21) | 0.80 |

| Chorioamnionitis, n (%) | 22 (11) | 33 (16) | 0.21 | 22 (12) | 33 (17) | 0.11 |

| Any antenatal steroids, n (%) | 168 (87) | 181 (87) | 0.41 | 168 (88) | 162 (85) | 0.55 |

| Low SES, n (%) | 24 (12) | 24 (11) | 0.76 | 24 (13) | 20 (11) | 0.63 |

| 5-min Apgar scorec | 9 (3) | 8 (2) | 0.02 | 8.0 (2) | 7.3 (2) | 0.003 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 81 (42) | 96 (46) | 0.48 | 81 (42) | 95 (50) | 0.15 |

| Outborn, n (%) | 7 (4) | 15 (7) | 0.12 | 7 (4) | 15 (8) | 0.08 |

PPROM, prolonged premature rupture of membranes; SES, social economic status.

Mean ± SD.

Toxemia was defined as hypertension, preeclampsia, or HELLP syndrome.

Median (interquartile range).

Nonrespiratory Outcomes

The majority of nonrespiratory outcomes were comparable between both epochs, with the exception of NEC ≥ grade II, which was significantly higher in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1 (Table 2). Mortality tended to be higher in the second compared to the first epoch, but this difference was no longer observed after excluding the infants born in the 24th week of gestation and adjusting for other possible confounders as described above (Table 3).

Table 2.

Respiratory characteristics and short-term clinical outcomes

| Variable | Total cohort |

Infants ≥25 weeks' gestational age |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004/2005 (n = 193) | 2010/2011 (n = 211) | p | 2004/2005 (n = 192) | 2010/2011 (n = 190) | p | |

| Intubation in DR/OR, n (%) | 66 (34) | 25 (12) | <0.001 | 66 (35) | 23 (12) | <0.001 |

| Inborn only, n (%) | 62 (33) | 17 (9) | <0.001 | 62 (34) | 15 (9) | <0.001 |

| Time to first intubationa, days | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 0.002 | 2.3 ± 3.0 | 3.0 ± 3.5 | 0.06 |

| Never intubated, n (%) | 68 (35) | 91 (43) | 0.11 | 68 (35) | 88 (46) | 0.04 |

| Number of intubations >1, n (%) | 51 (40) | 59 (47) | 0.26 | 50 (26) | 48 (25) | 0.91 |

| Timing of first intubation, n (%) | ||||||

| Intubation <72 h | 113 (59) | 86 (41) | <0.001 | 113 (59) | 74 (39) | <0.001 |

| Intubation <7 days | 116 (60) | 94 (45) | 0.002 | 116 (60) | 80 (42) | <0.001 |

| Intubation <14 days | 125 (65) | 113 (54) | 0.022 | 124 (65) | 96 (51) | 0.007 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilationb, days | 1.5 (7.2) | 0.5 (3.4) | 0.009 | 1.5 (7.2) | 0.4 (2.9) | 0.004 |

| Mean duration per episodeb, days | 1.3 (3.8) | 0.4 (2.0) | 0.002 | 1.3 (3.9) | 0.3 (1.9) | 0.002 |

| Air leak syndromec, n (%) | 15 (7.8) | 15 (7.1) | 0.65 | 15 (7.8) | 13 (6.8) | 0.55 |

| Nasal IMV, n (%) | 13 (7) | 50 (24) | <0.001 | 12 (6) | 38 (20) | <0.001 |

| Surfactant, n (%) | 104 (54) | 83 (39) | 0.003 | 104 (54.2) | 72 (38) | 0.002 |

| Caffeine, n (%) | 147 (76) | 200 (95) | <0.001 | 146 (76) | 182 (96) | <0.001 |

| Doxapram, n (%) | 7 (4) | 29 (14) | <0.001 | 6 (3) | 17 (9) | 0.018 |

| Dexamethasone, n (%) | 7 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.87 | 7 (4) | 3 (2) | 0.34 |

| Persistent ductus arteriosus, n (%) | 64 (33) | 64 (30) | 0.54 | 63 (33) | 52 (27) | 0.27 |

| Proven infection, n (%) | 78 (40) | 92 (44) | 0.52 | 77 (40) | 82 (43) | 0.60 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis ≥ grade II, n (%) | 9 (5) | 22 (10) | 0.03 | 9 (5) | 21 (11) | 0.02 |

| Periventricular malacia, n (%) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.12 | 6 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.12 |

| IVH any grade, n (%) | 51 (27) | 57 (27) | 0.43 | 50 (27) | 41 (23) | 0.24 |

| IVH > grade II, n (%) | 19 (10) | 13 (6) | 0.17 | 19 (10) | 9 (5) | 0.08 |

| Mortality at 36 weeks’ PMA, n (%) | 24 (12) | 40 (19) | 0.08 | 23 (12) | 28 (15) | 0.43 |

| BPD severity at 36 weeks’ PMA, n (%) | ||||||

| No BPD | 110 (57) | 103 (49) | 0.10 | 110 (57) | 100 (53) | 0.36 |

| Mild BPD | 14 (7) | 31 (15) | 0.02 | 14 (7) | 29 (15) | 0.016 |

| Moderate BPD | 29 (15) | 19 (9) | 0.06 | 29 (15) | 17 (9) | 0.022 |

| Severe BPD | 16 (8) | 16 (9) | 0.78 | 16 (8) | 16 (8) | 0.97 |

DR/OR, delivery room/operation room; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; PMA, postmenstrual age; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Mean ± SD.

Median (interquartile range).

Air leak syndrome was defined as pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or pulmonary interstitial emphysema.

Table 3.

Mortality and pulmonary outcomes at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

| 2004/2005 | 2010/2011 | Unadjusted OR |

Adjusted ORa |

Adjusted ORb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Mortality | 23 (12.0) | 28 (14.7) | 0.97 | 0.89, 1.05 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.90, 1.06 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.08 | 0.95 |

| Moderate or severe BPD | 45 (23.3) | 33 (17.4) | 0.74 | 0.50, 1.11 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 0.51, 1.20 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.48, 1.16 | 0.19 |

| Mortality or BPD | 68 (35.4) | 61 (32.1) | 0.91 | 0.68, 1.20 | 0.49 | 1.04 | 0.91, 1.20 | 0.56 | 1.08 | 0.94, 1.24 | 0.27 |

Values are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Only infants born at ≥25 weeks’ gestational age were analyzed. BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Corrected for gestational age, small for gestational age, chorioamnionitis, singleton, and outborn.

Corrected for confounders in first adjusted analyses including necrotizing enterocolitis.

Respiratory Outcomes

The proportion of inborn infants intubated in the DR dropped significantly, and fewer infants needed IMV at the different time points during the NICU admission (Table 2). The age at first intubation was significantly lower and the duration of IMV significantly longer in epoch 1. The percentage of infants with a GA between 25 and 30 weeks who were never intubated was higher in epoch 2 (46 vs. 35%).

The number of infants with no or severe BPD was relatively stable in both epochs. However, the proportion of infants with a GA between 25 and 30 weeks diagnosed with moderate BPD was significantly higher in the first epoch (15%) compared to the second epoch (9%) (Table 2). This resulted in a lower incidence of the combined outcomes moderate/severe BPD in epoch 2 (17%) compared with epoch 1 (23%), although this reduction was not statistical significant after correcting for all possible confounders. The combined outcome death or moderate/severe BPD was not significantly different (Table 3).

Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

The proportion of surviving infants assessed at 24 months' CA was 91 and 81% in epochs 1 and 2, respectively. Infants lost to follow-up did not differ in terms of patient characteristics and respiratory outcomes compared to those assessed (data not shown). The percentage of infants with a MDI or PDI less than −1 SD almost halved in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1, which was statistically significant after correcting for possible confounders present at birth. Following additional correction for the intermediates NEC and IVH, these differences remained statistical significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years' corrected age

| 2004/2005 | 2010/2011 | Unadjusted OR |

Adjusted ORa |

Adjusted ORb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Mortality | 25 (13.0) | 28 (14.7) | 1.13 | 0.68, 1.87 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.60, 1.59 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.49, 1.30 | 0.36 |

| MDI less than −1 SD | 25 (13.0) | 12 (6.3) | 0.55 | 0.29, 1.05 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.23, 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.24, 0.93 | 0.029 |

| PDI less than −1 SD | 26 (13.5) | 9 (4.7) | 0.39 | 0.19, 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.15, 0.71 | 0.004 | 0.35 | 0.16, 0.74 | 0.006 |

| CP | 8 (4.2) | 6 (3.2) | 0.89 | 0.32, 2.50 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.21, 2.01 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.26, 2.91 | 0.82 |

| NDI | 40 (20.8) | 19 (10.0) | 0.53 | 0.33, 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.32, 0.90 | 0.018 | 0.55 | 0.33, 0.93 | 0.024 |

| Mortality or NDI | 65 (33.9) | 47 (24.7) | 0.78 | 0.58, 1.05 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.56, 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.53, 0.97 | 0.03 |

Values are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Only infants born at ≥25 weeks’ gestational age were analyzed. MDI, Mental Development Index; PDI, Psychomotor Development Index; CP, cerebral palsy; NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment defined as having an MDI or PDI less than −1 SD, CP, or hearing or visual impairment.

Corrected for gestational age, small for gestational age, chorioamnionitis, outborn, singleton and Apgar score at 5 min.

Corrected for confounders in first adjusted analyses including intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis.

The rate of cerebral palsy and visual or hearing impairment was low in both epochs and did not differ significantly. Both outcomes NDI and the composite outcome death or NDI were significantly lower in epoch 2 versus epoch 1 after correcting for all possible confounders and intermediates (adjusted OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.93; and adjusted OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.97) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows, for the first time, that a policy of restricted use of IMV might be associated with improved neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants.

Previous studies have already shown that change in respiratory management started in the DR can impact respiratory outcome [20]. Oxygen need was no longer considered a symptom of respiratory distress syndrome, but of (transient) normal pulmonary transition. Since intubation and IMV were restricted to those needing resuscitation, the intubation rate in the DR dropped from 33% in epoch 1 to <10% in epoch 2, which is considerably lower than what has been reported in several large databases (48-65%) [1,10]. Although a considerable number of infants needed IMV during admission, the proportion was consistently lower in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1 at the time points 72 h, day 7, and day 14 of life. Furthermore, fewer infants needed IMV during the entire admission in epoch 2 (54%) versus epoch 1 (65%), indicating that our respiratory policy not only postponed but also prevented IMV. The proportion of infants needing IMV in epoch 2 of this study was lower than has recently been reported [11,21].

The duration of IMV almost halved in epoch 2 compared to epoch 1, indicating a successful policy of more aggressive weaning and extubation. As expected, infants in epoch 2 were more often treated with interventions reducing the need for IMV, such as caffeine, nasal MV, and doxapram [22,23,24].

The inclusion of infants born in the 24th week of gestation did not seem to change the majority of the abovementioned outcomes, suggesting that even these immature infants tolerate a noninvasive respiratory policy. However, this needs to be confirmed by future studies because of the limited number of infants born in the 24th week of gestation in this study.

The change in respiratory policy was also associated with a (modest) reduction in the incidence of BPD, mainly caused by a shift from moderate to mild BPD in epoch 2. After adjusting for possible confounders, the difference in BPD no longer reached statistical significance. The fact that the reduction in BPD between both epochs was modest (6%) could, in part, be explained by the fact that the BPD rate in 2004-2005 was already at the low end of the reported spectrum [11,21].

The most important finding of this study is a reduction in the combined outcome death or NDI at 24 months' CA in epoch 2 (24.7%) compared to epoch 1 (33.9%). This improvement was mainly caused by an almost 50% reduction in both MDI and PDI in epoch 2, although only the latter maintained statistical significance after correction for possible confounders and intermediates. The reduction in IMV and BPD as well as the increased use of caffeine in epoch 2 are all possible explanations for this improvement in neurodevelopmental outcome [4,5,25].

Of concern was the significant increase in NEC in epoch 2. Although this finding is not supported by other studies [26] and it does not seem to impact long-term outcome, future studies on noninvasive support policies need to monitor this adverse outcome closely.

The limitations associated with a retrospective study design may have affected the validity of our findings. First, in the time between both epochs, other nonrespiratory changes in care may have affected the main outcomes. A clear example was the difference between both epochs in active treatment of infants born at 24 weeks' gestation. For this reason, we analyzed the outcome data after excluding these infants. To account for other differences in case of a mix between the two epochs, we corrected the multiple logistic regression analyses for possible confounders and intermediates associated with one or more of the main outcomes. Only the analysis taking into account all possible confounders or intermediates were used for final data interpretation. However, despite this conservative approach, we cannot exclude some residual confounding by other small changes in care over time. Second, we were not able to determine the rate of physiological BPD as the oxygen reduction test was not used in both epochs. This may have resulted in an overestimating of the true incidence of BPD and hampers comparison of our BPD rate with more recent studies [22]. Finally, the change in BSID version over time forced us to convert the test results of the BSID-II to allow for epoch comparison. Although studies assessing the impact of such a conversion are reassuring, we cannot rule out that version-related differences may have affected our findings [12]. To strengthen the validity of our finding, we used a conservative PDI conversion of 10 points.

In conclusion, this study shows that a policy of restricted use of IMV in both the DR and the NICU is feasible in preterm infants and might be associated with a lower risk of the combined outcome death or NDI at 24 months' CA. Further studies in larger series are required to confirm these findings.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Sources

There was no external funding for this project.

Author Contributions

R.J.S. Vliegenthart contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analyses and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. W. Onland contributed to the design of the study, data analyses and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. A.P.M. De Jaegere contributed to the design of the study, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. A.G. van Wassenaer-Leemhuis contributed to the design of the study, data analyses and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. C.S.H. Aarnoudse-Moens contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the analyses, and writing of the manuscript. A.H. van Kaam contributed to the design of the study, data analyses and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. R.J.S. Vliegenthart wrote the first draft of the manuscript. No payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Appendix

Demographic, patient characteristics and clinical outcomes assessed for each patient: outborn (defined as born in a regional level II hospital), GA, birth weight, small for gestational age defined as birth weight <2 SD according to the Dutch reference curves, gender, Apgar score, mode of delivery, multiple pregnancy, prolonged premature rupture of membranes, use of antenatal corticosteroids, maximal respiratory support in the DR, mode and duration of respiratory support in the NICU, air leak syndrome, use of postnatal corticosteroids, use of exogenous surfactant, caffeine, and doxapram, persistent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage grade III or IV, periventricular leukomalacia, culture proven sepsis, and mortality at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age and hospital discharge. The social economic status score was indexed using ZIP code tabulation areas [27].

References

- 1.Soll RF, Edwards EM, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Morrow KA, Buzas JS, et al. Obstetric and neonatal care practices for infants 501-1,500 g from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132:222–228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JD, Carlo WA. Pulmonary complications of mechanical ventilation in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenkranz RA, Walsh MC, Vohr BR, Jobe AH, Wright LL, Fanaroff AA, et al. Validation of the National Institutes of Health consensus definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1353–1360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh MC, Morris BH, Wrage LA, Vohr BR, Poole WK, Tyson JE, et al. Extremely low birthweight neonates with protracted ventilation: mortality and 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Pediatr. 2005;146:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vendettuoli V, Bellu R, Zanini R, Mosca F, Gagliardi L, Italian Neonatal Network Changes in ventilator strategies and outcomes in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F321–F324. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulder EE, Lopriore E, Rijken M, Walther FJ, te Pas AB. Changes in respiratory support of preterm infants in the last decade: are we improving? Neonatology. 2012;101:247–253. doi: 10.1159/000334591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jaegere A, van Veenendaal MB, Michiels A, van Kaam AH. Lung recruitment using oxygenation during open lung high-frequency ventilation in preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:639–645. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-351OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson JA, Kamlin CO, Vento M, Wong C, Cole TJ, Donath SM, et al. Defining the reference range for oxygen saturation for infants after birth. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1340–e1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rossem MC, van de Loo M, Laan BJ, de Sonnaville ES, Tamminga P, van Kaam AH, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in a referral-based health care system. J Pediatr. 2015;167:540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. ed 2 (manual) New York: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lees CC, Marlow N, van Wassenaer-Leemhuis A, Arabin B, Bilardo CM, Brezinka C, et al. 2 year neurodevelopmental and intermediate perinatal outcomes in infants with very preterm fetal growth restriction (TRUFFLE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuner G, Fields AC, Wittke A, Lopprich M, Pietz J. Comparison of the developmental tests Bayley-III and Bayley-II in 7-month-old infants born preterm. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regev RH, Reichman B. Prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation – double jeopardy? Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:453–473. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, Acaia B, Merlo D, Ronchi A, Ossola MW, et al. Chorioamnionitis and neonatal outcome in preterm infants: a clinical overview. The J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:1525–1529. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1053862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossain S, Shah PS, Ye XY, Darlow BA, Lee SK, Lui K, Canadian Neonatal Network; Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network Outborns or inborns: where are the differences? A comparison study of very preterm neonatal intensive care unit infants cared for in Australia and New Zealand and in Canada. Neonatology. 2016;109:76–84. doi: 10.1159/000441272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radic JA, Vincer M, McNeely PD. Temporal trends of intraventricular hemorrhage of prematurity in Nova Scotia from 1993 to 2012. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15:573–579. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.PEDS14363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy K, Yanowitz TD, DiGeronimo R, Dykes FD, Zaniletti I, Sharma J, et al. Short-term outcomes for preterm infants with surgical necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol. 2014;34:736–740. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmolzer GM, Kumar M, Pichler G, Aziz K, O'Reilly M, Cheung PY. Non-invasive versus invasive respiratory support in preterm infants at birth: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemyre B, Davis PG, De Paoli AG, Kirpalani H. Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) for preterm neonates after extubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD003212. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003212.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, et al. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2112–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamazaki T, Kajiwara M, Itahashi K, Fujimura M. Low-dose doxapram therapy for idiopathic apnea of prematurity. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:124–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, et al. Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893–1902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aly H, Massaro AN, Hammad TA, Narang S, Essers J. Early nasal continuous positive airway pressure and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2009;124:205–210. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Graaf JP, Ravelli AC, de Haan MA, Steegers EA, Bonsel GJ. Living in deprived urban districts increases perinatal health inequalities. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:473–481. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.735722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]